Putting Lifeworlds at Sea: Studying Meaning-Making in Marine Research

- 1Department of Social Sciences, Leibniz-Center for Tropical Marine Ecology, Bremen, Germany

- 2Institute of Sociology, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany

An individual's “lifeworld” guides perceptions, the attachment of meaning and in sum, the interpretation of reality in everyday life. Yet the lifeworld (Ger. Lebenswelt) has been an undertheorized concept within interdisciplinary marine research. Through a two-stage analysis, we critically engage with the philosophical foundations, heuristic value and the methodological versatility that the interpretivist concept of the lifeworld stands to offer, drawing from contemporary marine scholarship. With two illustrative case studies exploring the lived realities of vastly different waterworlds in rural Uzbekistan and Sri Lanka, we further engage with the strengths and limitations of integrating a lifeworlds analysis into interdisciplinary work on localized perceptions. As a second step, we analyze the efficacy of adopting a phenomenological-lifeworlds approach in order to inductively explore diverse realities of coastal and sea-based peoples, while acknowledging the terrestrially-bound and anthropocentric genesis of the lifeworld as a concept. Therefore, in order to enliven hybrid thematic currents, conceptual debates and methodologies on “marine lifeworlds” on its own terms, we propose two thematic vantage points for interdisciplinary intervention by: (a) critically engaging with cognitive-material meanings and lived interpretations of “saltwater” realities; (b) tracing multiple modes of sociality and being with/in-the-world that go beyond human entanglements. In sum, we argue that while the lifeworlds concept affords spaces through which to study the complexities and ambivalences rife in surface-level perceptions, it promises the means with which to sidestep over-simplistic inferences to the vague and embattled notion of “culture,” while widening horizons for reflective and experimental-experiential lines of inquiry.

Introduction

“Only the magic and the dream are true—all the rest's a lie.”

–Rhys (1999)

Jean Rhys' novel, set in nineteenth century plantation Jamaica, offers a postcolonial feminist re-telling of the tragic tale of “Bertha” Mason, Edward Rochester's mad wife, who remains locked away in an unforgiving turret of Charlotte Bronte's Jane Eyre. In the latter Victorian novel she is dragged out, fighting tooth and claw, more harpy-like than animal, more mythological than misplaced. Yet in Rhys's (1999) Wide Sargasso Sea, Bertha—or Antoinette Mason—a fiercely intelligent and imaginative young Creole woman is presented in a very different lifeworld that is her own, on an island far removed from the cultivated frostiness of English country life among the landed gentry.

It is this lifeworld that the stranger—Rochester—whom she weds, comes to fear and ultimately loathe, with its tropical “mountains and hills, rivers and the rains…its sunsets of whatever color… its beauty and its magic…its indifference and cruelty.” The growing revulsion that he harbors toward his new wife lies inimically coupled to this antithetical world that he covertly delights in othering—replete with disease and rumor, obeah ritual and languid decadence. To Rochester, Granbois seems unreal and hallucinatory, while England appears surreal and dream-like to many of the young Anglophone women of the West Indies, yearning for “return” to an island they had never set foot upon. It is this slippage between embodied presence and absence, of wakefulness and the dream-like, in which the two lifeworlds in the Wide Sargasso Sea are so intimately interwoven.

Yet, what is in a lifeworld and why should it matter in community-based research? Within ongoing debates on inter and transdisciplinary approaches in addressing “real life” problems, the inclusion of local lifeworlds in order to guide researcher reflexivity, in determining research processes and the interpretation of findings have repeatedly been stressed (Pohl and Hadorn, 2007). While the notion of “lifeworlds” (Ger. Lebenswelt) is often used metaphorically in order to place emphasis on the salience of local perceptions and worldviews, its conceptual and empirical uses and limitations remain under-researched across the coastal and marine social sciences.

Since its formative stages of conceptual development the “lifeworld” has remained a relatively nebulous and opaque concept when perceived from outside the disciplinary frames of interpretive sociology and psychology. Furthermore, it is often perceived as being methodologically elusive and complex for practical application in empirical field-based contexts. While much ethnographic analyses bearing the term lifeworlds exist, they arguably pay scant lip-service in concretely conceptualizing what precisely is meant by the term. Furthermore, the concept offers little recourse to social scientists that remain wary (and weary) of wielding the hollow notion of “culture” as an explanatory force, given its dangerous ambiguity and inclination toward essentialist theorizing.

Rather than attempting to tame and pin down a linear, all-encompassing definition of lifeworlds, this paper serves as an open invitation to socio-environmental scholars and policy analysts who are increasingly turning toward perceptions-based, interpretative and social constructivist thinking in order to invigorate community-based research.

The second section provides a kaleidoscopic glimpse into the various threads of lifeworld theorizing, drawing attention to the often slippery axes between the following dualisms—(a) the individual and the collective, (b) the experiential and the ideational, (c) of appearance (exteriorized) and essence (interiorized) and (d) the subjective (first person) and the objective (third person). The third part of the paper proceeds to reflect on the flexible application of the lifeworld concept through the use of two empirical studies of fluid waterworlds (see Anderson and Peters, 2014), one implicating freshwater and the other saltwater.

Following on from an empirically grounded discussion, the fourth section offers critical insights into whether the study of “marine lifeworlds” holds much conceptual purchase and empirical relevance at all, given the vast corpus of maritime and coastal-related social science research that has embraced an interpretive perspective, though not necessarily a phenomenological one. While briefly attending to some of the reasons for the apparent absence of marine lifeworlds-inspired research as opposed to more coastal-related foci, we provide critical points of departure and thematic interventions through which the study of marine epistemologies and ontologies (i.e., ways of knowing and being) may enliven existing interpretivist research endeavors.

Unbraiding the Lifeworld: The Anatomy of a Concept

The understanding and study of social reality has been a core preoccupation across diverse sub-disciplines including social philosophy, existential anthropology, interpretivist sociology, and cognitive psychology. Since the early 1900s, the notion of the “lifeworld” has often appeared in the social sciences and the humanities, as an integrative concept with which to describe the particularities of an individual's lived experience in everyday life. However, before engaging with this comparatively hydra-headed term, the very philosophical and epistemological foundations of the lifeworld approach warrants further exploration.

Contemporary approaches to lifeworlds thinking, emerged as the progeny of two vastly influential theoretical traditions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, particularly across the Austro-German and French philosophical milieu. At its broadest, phenomenology—as a philosophical tradition and movement—can be traced back to the Austrian School founded by Franz Brentano that built upon classical Hegelian notions of the experience of being in the world. Broadly framed, early phenomenological philosophers like Husserl (1970), Heidegger (1977), Mannheim (1929), Merleau-Ponty (1981), and Lyotard (1991) were concerned themselves with the structures of experience in everyday understanding, and in the interplay of common sense and how particular forms of “knowing” and “being” arise from experience (Roth, 2004; Bengtsson, 2013). These currents vastly influenced the work of humanist thinkers and writers like Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, and Simone de Beauvoir, as they engaged with broader interrogations of being and not-being, social alienation, otherness, and nihilism.

Phenomenology is primarily concerned with the experience of “being there” (Ger. Dasein)—in all our humanness—that far transcend the surface meanings of ordinary perception and experience. Modes of existence were understood as being patterned by and grounded in very situated spatio-temporal, socio-relational and symbolic spheres of everyday life. In the contemporary context, phenomenological approaches still remain influential within fields such as area studies, urban and medical anthropology, peace and conflict studies, natural resource governance, educational psychology, social work, nursing practice, management research, and disability studies, incorporating diverse methods spanning the qualitative-interpretive, quantitative and the poetic-reflective (see Nieuwenhuys, 1994; Ehrich, 2005; Jackson, 2005, 2012; Johansson et al., 2008; Oberkircher and Hornidge, 2011; Finlay, 2013; Siriwardane, 2015). Phenomenology can be therefore seen as a distinct epistemological philosophy—a style of thinking. Scholar-practitioners, particularly within the field of critical pedagogical research, often drew attention to its ontological, existential currents, treating it as a “way of being” or as a philosophy of life in itself (Hultgren, 1995, p. 379). This position bears far-reaching implications on how research practice and writing could be ethically and reflectively re-learned, an aspect that we will be exploring in greater depth.

The second strand of lifeworlds thinking originated from the hermeneutic tradition, latterly branching into the sub-field of phenomenological hermeneutics. Hermeneutics can be broadly defined as the theory of interpretation (Dahlberg et al., 2008, p. 66), implicating scholars such as Gadamer (1975) and Ricoeur (1974), who were particularly engaged in exploring the gaps inherent between perception, language, embodied expression and action, together with the wider processes of storying human experience. Later work like that of Johansson and Emilson (2010) and Bengtsson (2013) grew out of the Gothenburg tradition with a focus interaction-based meaning-making, for example in the context of educational research on preschool children and their non-linguistic (yet highly expressive) routines of inter-subjective play-based worlds.

While it is evident that there is no singular way of defining and doing phenomenological lifeworlds research, it must be borne in mind that phenomenology, and consequentially early theorizations of the lifeworld, did not explicitly engage with matters of empirical research. Indeed, early phenomenological thinking stood as a distinctly philosophical (and ethical) project. For thinkers like Edmund Husserl (1970), who first introduced the term “lifeworld” in a treatise written between the wartime years of 1916 and 1917, the notion arguably stood out as a dynamic counter-concept to the privileged role of scientific rationality and the crisis of the modern technological world. Phenomenology reflected the disenchantment of contemporary thinkers with the ideals of natural science and technology as “models for philosophical engagement” (Madsen, 2002, p. 10). The lifeworld then stood, not as a radical juxtaposition or dialectical Other, but as a world of commonly shared experience, encompassing worlds of belief (doxa), of preconceived notions of prejudice and illusion for example. In this light, the world of scientific rationality and knowledge production was but one lifeworld among others.

While we have thus far explored the ontological and epistemological foundations of the lifeworld approach, how then can this multi-stranded approach be accessed with some degree of conceptual clarity? Husserl never quite as cogently defined what was meant as a lifeworld. Moreover, his work left to be asked why “worlding” metaphors mattered when exploring perceptions, attitudes and meaning-making processes. In other words, would not a singular focus on self-expressed perceptions, not seem as sufficient as empirical facts?

These questions take us back to the German philosopher Heidegger (1977), who was arguably the first to integrate phenomenology with classical hermeneutics, borrowed from neo-Kantian, Kierkergaadian, and Weberian theoretical currents (Bengtsson, 2013). From a Heideggerian vantage point, perceptions were mere surface articulations. They were often conscious and could be rationalized logically, yet their salience, preconditioning and the more subtle tacit forms of knowing, thinking and feeling that still remained relatively less apparent. Perceptions then, at its simplest, were akin the proverbial tip of the iceberg. Often, the distance between perceptions and actions, believing and doing, could not simply be explained by chipping away at subjective attitudes or collectively recognized norms and mores.

The lifeworld to Heidegger was about “being-in-the-world” (Ger. in der Welt sein). What this concretely translates to is the conceptualization of phenomena and experience that are lived and inter-subjectively experienced, yet could still remain tacit. It differed from Husserl's critique on the “natural attitude” (Ger. natürliche Einstellung) of phenomena as materially known and felt (Dahlberg et al., 2008, p. 33). Therefore, multiple lifeworlds—as differently conceived and lived—could exist in a single material realm, for example a coastal stretch inhabited by seaweed farmers, dive operators, aquaculturalists, hoteliers and naval entities.

However, Heidegger's conceptualization of the lifeworld concept sat within this wider philosophical project, and was a long distance away from being empirically translatable for research practice. For the French philosopher Merleau-Ponty (1981), the lifeworld approach adopted a more differentiated hue, which he conceptualized as “being-to-the-world” (Fr. entre au monde), in which the human body (and its embodied practices of everyday life) comprised the primary site of knowing, feeling and being. In his view, the “Eye” and the “Mind” (implying the Cartesian mind-body dualism) were not disconnected but mutually reinforcing, in which the world came to be interpreted and known through how it was materially, relationally and symbolically felt. In this light, it remains telling why interpretive scholarship within the fields of medical and educational psychology and disability studies for example, tend to be influenced by Merleau-Ponty's foundational work on embodiment. Moreover, there exists a recent and steadily growing body of marine/maritime scholarship that attends to the affective and multisensory meanings and subjectivities produced by dwelling with the sea—whether in terms of “finding one's sea legs” as an embodied experience of enskilment related to fishing and sea navigation (Pálsson, 2000), or through (masculinist) sensibilities of getting high on a “stoke” when surfing a wave (Evers, 2004).

Ultimately however, it was the Austrian sociologist, Schütz (1932, 1960) who consciously attempted to extricate lifeworlds thinking as a purely theory-based endeavor, into a practical concept for empirical analysis. Schütz, like Merleau-Ponty, was influenced by early Husserlian currents, but his primary focus rested on locating patterned structures through which lifeworlds could be understood. For him, the very act of conceptualizing (and contextualizing) lifeworlds—both literally and metaphorically—as “worlds” (i.e., domains or realms of experience, knowing, doing and feeling), was paramount to the exercise of grounding the concept. As he posited, “in using the term ‘world’…we mean only that different people are consociates, contemporaries, predecessors or successors to one another and that they accordingly experience one another and act upon one another in the different ways in question” (Schütz, 1960, p. 143).

For Schütz, the lifeworld was bound through temporal and spatial dimensions comprising four interlocking socio-material worlds. The individual's immediate environment, the social world of contemporaries (Mitwelt), interlocks with the precedent world of predecessors (Vorwelt) and successors (Folgewelt). While the immediate environment (Umwelt) appears to be shaped by direct, close relationships to family members and friends, the surrounding world (Mitwelt) is characterized by the interaction with those actors and social structures potentially subject to the individual's personal experience. This experience stands in relation to the individual through typification—the process of conceptually identifying, differentiating, naming, sorting, and assigning symbolic meaning to perceived material and relational phenomena, that begins in infancy. As the Vorwelt is shaped by relationships to ancestors and interpretations of the past, the Folgewelt is shaped by relations and actions directed to/at the future (Schütz, 1932, p. 160). Together, these four worlds of the individual constitute the reality of everyday life, or the Schützian interpretation of the “lifeworld.”

It was for the American-Austrian-German sociologists Berger and Luckmann (1967), that the differentiation between objective and subjective lifeworlds appeared paramount in adding more nuance to the interpretive study of reality. The subjective lifeworld, formed via typifications, constitutes the researchers' own lifeworld including those that are encountered during the research process. On the other hand, the objective lifeworld however appears as the naturalized milieu, setting spatial and temporal boundaries that are concretely lived, and may not be apparent within collective consciousness. These boundaries however are not simply limiting; they are generative in the sense that the spatial-temporal scope of an individual's lifeworld directly depends on the zone of operation” (Wirkzone) characterized by the geographic, social, as well as the mental mobility of a person. Therefore, diverse practices of small-scale as well as industrial fishing are not merely treated as a livelihood, but as a way of being-with-the-world and as “a way of life” (Weeratunge, 2009).

Yet, at this point it is must be noted that a Schützian reading of lifeworlds can be critiqued for its focus on the individual as a primary subject of analysis. Thus, collective lifeworlds, were somewhat simplistically interpreted as the additive stratification of individual experience, making for the interpretation of “shared reality” as merely the sum of its constituent parts. Indeed, the work of Berger and Luckmann (1967) proved influential in sociological institutionalist theory building, given its heuristic methodology in studying normative change, and the interplay of collective roles, norms, discourses and practices (see March and Olsen, 2005). Yet arguably, the analytical tools offered in tracing trajectories of institutional change remain relatively less defined.

Meanwhile, two other influential German lifeworld theorists that warrant brief discussion: the Frankfurt School critical theorist Habermas (1955, 1984), and the phenomenological hermeneutic philosopher Gadamer (1975). In combining Chicago School pragmatism and early currents of structural-functionalist thinking, Habermas' view of the lifeworld stood in stark contradiction to what he defined as the “systems world” constituting the exteriorized rationalization of everyday action, as evident in modern bureaucracy for example. It was then the focus on the interaction between the two realms—in which the systems-world often “colonized” an individual's lifeworld, through tacit influences such as media practices that steer collective thinking and action. One of the more compelling tropes through which this tension is illustrated can be found within the substantial raft of fisheries-related governance literatures and environmental management practices that explores interactive encounters between bureaucratic, scientific and locally-situated knowledges, particularly within diverse co-management structures and other communicative contexts, whether more participatory or top-down (see Wilson and Jacobsen, 2013). The work of Gadamer (1975) on the other hand, took Husserl's conceptualizations further by integrating the notion of Vorurteile (preconceptions). His work contributed to reflexive praxis-oriented research that set the foundations for a practiced attitude of exposing and confronting pre-judgements, particularly through intersubjective encounters. Thus, a Gadamerian reading potentially offers conceptual insights into questions of individual agency and resistance, regulatory and informal norm-based compliance, constituting interwoven thematic currents that are gaining increased traction within interdisciplinary fisheries research.

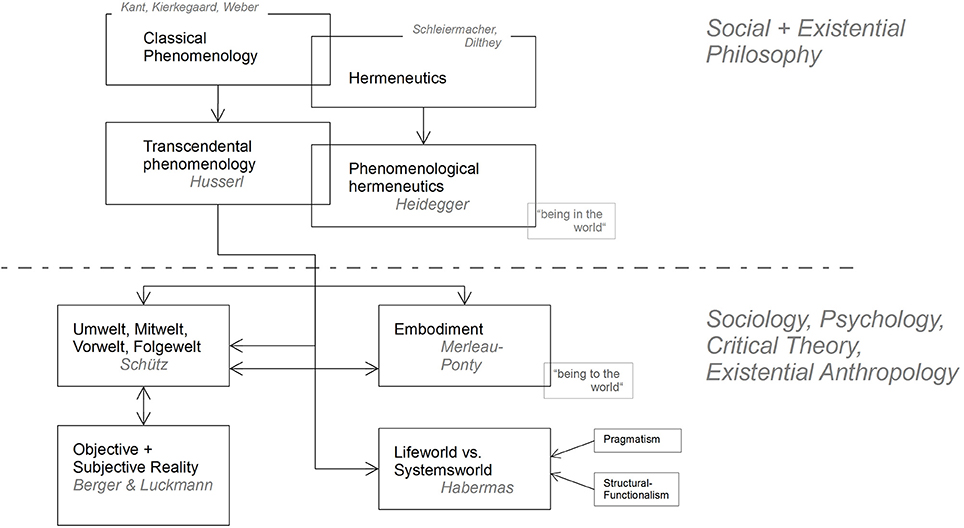

In order to chart their diverse epistemological currents, Figure 1 depicts how the concept of the lifeworld evolved.

Figure 1. The Building blocks of the Lifeworlds concept. The chart aims at establishing clarity, yet does not make the claim of being exhaustive or non-expansive. Nor does it claim to holistically represent the diverse ontological and epistemological currents that influenced the foundational theorists presented.

Having explored the salience of understanding researcher lifeworlds, how does one set about reflecting upon, documenting and storying the lifeworlds of others? As the following section illustrates illustrates, since the concept entered the realm of social science discourse, much has been done in the way of creatively translating and operationalizing lifeworld approaches into research processes, while simultaneously guiding researcher ethics and reflexivity. Moreover, it critically examines the conceptual and empirical advantages and limitations of applying a lifeworlds approach to contemporary research on two different types of lived “waterworlds”—one in an arid, landlocked freshwater site in Central Asia, and the other constituting a saltwater milieu in a South Asian coastal setting.

Operationalizing Lifeworlds in Empirical Research

The paradox of attending to and understanding the substance of individual lifeworlds, particularly if it is interpreted as constituting the implicitly lived or presupposed realm of everyday life, has been a central topic of debate within anthropological and sociological research. First how can the tacit and unexpressed (or inexpressible), emerge to the surface of consciousness? Second, how can a researcher—particularly one who is relatively distanced from the lifeworld of those she partners—explore at times unexpressed meanings? Thus, the attempt at bridging this epistemic distance, between the interiorized (implicit) and the exterior (the manifest), tends to emerge as a leap of faith.

Furthermore, what questions of power and authorial voice materialize when claims are made about conclusively studying and writing about individual and collective lifeworlds? On one hand, lifeword theorizations have almost exclusively been individual-centered. On the other, the ability to write about lifeworlds, may run the risk of potentially strengthening truth-claims through textual preeminence. This double-bind, between the persuasive currency of being able to extract knowledge on lifeworlds, and the (em)powered researcher to grasp the otherwise implicit and tacitly known may potentially result in a dangerous cocktail of epistemic privilege and representational objectivity. Researcher positionality and reflexivity have therefore remained a central concern, particularly within the scope of field-based qualitative research. Ethnographers in particular have been doubly conscious of the early colonial origins of their enterprise, and continue to contribute to lively debates on the ability of fully grasping meanings and implications by one's socio-political positioning during fieldwork (see Lynch, 2000).

In contemporary phenomenological lifeworld research, this is often achieved through a three-step iterative process in which experience is bracketed, otherwise known as “bridling.” The first stage entails a systematic effort to suspend judgment, by stepping outside preconceived notions of how things are expected to seem and to work. The second stage requires the conscious effort of dwelling with and within the phenomena in question. Put differently, a researcher's attention may be re-focused to her content of what is experienced, and what makes experience possible in the first place. The process of cultivating generative openness to the first and second stage interpretations of meaning comes to bear, allowing one to consciously compare alternative templates and mental maps of how the same phenomena has been interpreted in the past. Taken together, these steps prevent a field-based researcher from acting upon pre-existing assumptions and interpreting lived realities too hastily. Moreover, it lays bare the fact that as researchers, “we can be self-reflective without being self-aware” Dahlberg et al. (2008, p. 165). This quotation takes into account the significance of experience that influences further actions, and the consequences that come about by reflecting with, rather than on others.

Johansson et al. (2008, p. 2) see this as a concrete form of bridling, which does not make the pretense of abandoning all pre-assumptions, but instead embraces the possibility of “slowing down the process of understanding in order to see the phenomena in a new way,” often integrating multisensory subjectivities and relationalities. For example Peters (2010) in problematizing scholarly representations of the sea as a mere metaphorical image of life on shore, draws attention to the very linear act of objectifying the sea through dynamics of voyaging, trade, empire-building and territorialization. Therefore, in (re)centering fluidities beyond spatially bounded terms, Anderson and Peters (2014, p. 5) calls for the imperative need to enliven scholarly engagements with diverse marine epistemologies that see (water)worlds as being in “flux, changeable, processual and in a constant state of becoming.”

As varied as the conceptual interpretations of watery lifewords has been, so have been the methodologies with which to research them. Oberkircher and Hornidge (2011) operationalized the phenomenological concept in the form of “water lifeworlds” through a contemporary Schützian interpretation by paying closer attention to how objective and subjective realities were coupled in Khorezm, Uzbekistan. Their methodological substance therefore entailed social facts and processes they themselves observed (e.g., everyday actions and decision-making trajectories) combined with the discursive-symbolic world of narrative reflections, mental maps and new or emergent concepts. Once again, the epistemological frame was driven by the particular problem-based research puzzle in question. They examined why perceivable forms of water saving were hardly present in an arid terrain such as Khorezm, and across a socio-cultural milieu that seemingly articulated counter-rationalities on the sacredness of water and its centrality in establishing social status.

By attempting to understand nuances inherent in the in-betweenness of these divergent rationalities, the temporal and spatial boundedness of the “objectively” perceived lifeworld was first explored. This entailed how farmers constructed their picture of time and space alongside diverse water users and managers. Furthermore, these lifeworlds comprised meanings about vegetation seasons, flows of freshwater, and how times of scarcity and abundance were cognitively labeled. As a second framing, typologies, values, and institutions (as rules, norms, and rationalities) were explored. In particular, they focused on how individuals compared, categorized and classified their diverse Khorezmian waterworlds. The authors did this by identifying several layers of typologies: (a) types of water (for example locally embedded meanings around hard water, muddy water, and freshwater, literally translated as being delicious); (b) types and roles of people (for example diverse groups of “upper people” in the social hierarchy), “water persons” linked to the ancient institution of mirabs in Central Asia, fermers or large farm operators etc. and (c) types of land.

These boundaried pictures and typologies were compared with intersecting values and institutions—as discursively articulated, for example, through diverse state-led management principles, commonsensical logics and socio-religious rationalities on water provision and use. What the study drew attention to was why the rationality of water saving stood out as a “missing concept” in these diverse water lifeworlds, despite the ubiquitous Uzbek expression—suv hayot— or water is life (p. 406). By squarely drawing out and comparing rationales that prevent water saving as opposed to those that valorized the need to do so, the authors drew attention to the seemingly “messy” oscillation of lifeworld dynamics as they unfolded amid the complexities of everyday life. As we proceed to illustrate, this contemporary Schützian use of lifeworlds phenomenology, as a means to study problem-centered empirical questions, offers a number of conceptual and methodological advantages, as well as potential limitations and pitfalls.

On the other hand, Siriwardane's (2015) island ethnography on fisher lifeworlds in postwar Sri Lanka, with a distinct focus on the interactions between geographically and ethno-religiously diverse groups of migrants, settlers, and locals offers a different starting point. In asking why particular fisher collectives were othered as veritable “outsiders” or strangers, the study drew inspiration from existential anthropological readings on lifeworlds (see Jackson, 2005, 2012; Das, 2006). In this context, the “everyday” was taken as a realm that was not simply normed, routinized and rendered ordinary, but also as a site of active production, particularly in the way that power asymmetries come to be produced and contested. Moreover, in forewarning against the tendency of treating the concept the lifeworld as a “blanket term to encompass and ‘explain away’ every (ambiguous) facet of lived life” (Siriwardane, 2015, p. 96), the lifeworld concept was reshaped to suit everyday translocal and livelihood-based experiences and sensibilities.

At first glance, local hostilities directed at bilingual fisher migrants who shared long biographical histories of seasonal mobility seemed intuitive. They often encamped near local settlements that practiced similar forms of craft-based fishing. Their apparent bilingualism also actively worked in the disfavor of other migrant groups, given the fact that many continued to mask outward expressions of hybrid ethno-linguistic belonging, particularly when interacting with locally embedded military institutions. Yet, upon further exploration, it could be argued that the very rationalities around belonging, place-based identities, (historic) social presence, and “home” did not always cohere. The normative underpinnings through which communal insiders and outsiders were differently framed lay in a host of interpretations entailing crisscrossing: (a) pioneer narratives (i.e., “Who fished here first,” “Who cleared this land?”), (b) discourses on ancestral belonging and homeland (e.g., the primacy of having lived in the east coast, despite having been serially displaced over wartime), (c) biographical livelihood identities bound through “blood” and inter-generational enskilment, and (d) navigational imaginaries and historic legitimacies of mobility, through west-east coast sojourning. The institutionalized backdrop against which postwar militarized insider-outsider frames were being established was hardly ever articulated when exploring inter-group amity or hostility. For example, the vorwelt (pre-world) of bilingual fisher migration trajectories during wartime established encampments that were perceived by local residents as sites of exemption and rule breaking. This further exacerbated localized antagonistic perceptions, even between diverse migrant groups.

In comparing different lifeworld conceptualizations between both Oberkircher and Hornidge (2011) and Siriwardane (2015), it can be ascertained that such phenomenological approaches enable researchers, often not trained in field-based qualitative ethnographic work, to explore local terms through meanings (as lived) that go far beyond their semantic definitions and terminology. For example, if the pervasively uttered phase suv hayot was taken literally, as a blanket cultural expression defining Uzbek life—the paradoxes around practices that otherwise imply that water is unproductively allocated and used across the Uzbek hydraulic bureaucracy, would have remained relatively underexplored. In a similar vein, homogenizing all migrant fishers as strangers and outsiders would have led to the problematic glossing over multiple modes of sociality and ways of relating-to/with-the world (vernacularly theorized as sambandam) along liminal coastlines. Thus, the close attention paid to what seemed at face value as contradicting realities, enabled both studies to elude the trap of over-simplified and essentialist readings of localized “culture.”

Furthermore, turning to the lifeworld as an empirically applied methodology enables researchers to interrogate their own lifeworlds and potentially, check biased western-centered rationales and framings of aspects such as time, space, notions of reciprocity, and systems of socio-economic exchange. While this opens up collaborative spaces for co-production and interpretation of data between researchers and those they partner, and for self-reflecting on epistemic power and privilege, the lifeworlds approach also enables us to acknowledge and capture nuance and ambivalence. The distance between “representation and practice” (Busby, 2000, p. 34), and what is discursively articulated and what is ultimately enacted, often appears as a central trope in localized fisheries research for example, taking contexts in which institutional norms are both sanctified as well as broken under specific circumstances (Siriwardane, 2015, p. 147). The lifeworlds approach therefore calls for a cultivated sense of epistemological un-knowing, embodied in the German phenomenological notion of Gelassenheit (of letting be or to dwell, Dahlberg et al., 2008, p. 81 and 100).

The concept may also act as an epistemological starting point that can be used across diverse socio-cultural and regional contexts. While the concept may provide a heuristic vantage point through which a non-Eurocentric de-centered study could be envisaged, its claim toward epistemological universality may also act to its disadvantage. For example, phenomenology remains a deeply humanistic endeavor. Therefore, the lifeworld as a concept is inevitably an Anthropos-centric one, which encompasses more than just human interactions and engagements. While social meanings around inter-species relations (for example values toward non-human sentience for example), may visibly appear within lifeworlds writing, the means through which socio-nature can be seen as a subject possessing agency (and not passively objectivized as foreground that is acted upon) still remains fertile ground for further theoretical work (see Kohn, 2013; Viveiros de Castro, 2016).

Meanwhile, a commonly articulated limitation of the lifeworlds approach can be found in its methodological individualism. The stratification of individual experience is seen as constituting collective or communal lifeworlds, a reading that has often been critiqued for its simplicity and inability to account for normative transformations. The old quandary of seeing and describing the world through the eyes of others remains a paradoxical task. Typologies and typifications therefore serve to essentialize and legitimate particular interpretations of reality, often in ways that may be complicit to existing power inequalities and forms of social injustice, for example politically legitimated ethno-racial, gendered and class-based classifications.

Both Oberkircher and Hornidge (2011) and Siriwardane (2015) point toward the limitations inherent in typologizing “categories” of people as if social identities were container-like constructs, even if these labels were to an extent self-assigned. At the same time, their work allude to the difficulty in formulating alternative framings, which may well be far removed from daily discourse and practice. Therefore, by no means does this critical discussion stand to offer pat solutions to long-standing and debated questions on the preeminence of focusing on individuals as a unit of analysis, or on the other hand, on groups and collective framings. Moreover, the age-old philosophical agency-structure debate that our discussion forecloses further problematizes the dialectical relationship between individual capacities and freedom of choice, against the inherent constraints set by institutional rules and wider societal norms.

As the following section proceeds to illustrate, the use of phenomenological lifeworlds has remained a marginal current, particularly across interdisciplinary coastal- and marine-related social science scholarship. However, as we proceed to argue, “marine lifeworlds”-inspired research (although not explicitly having drawn on phenomenological currents) have historically constituted a vast corpus of work, particularly in the fields of maritime and marine anthropology, together with coastal and cultural geography. While fisheries-related accounts of diverse “peoples of the sea” have often depicted an anthropos-centric bias, we further explore what inclusionary forms of more-than-human lifeworld research could be further pursued in ways that more expansively engage with the newly emergent sub-fields of multi- and interspecies ethnography. It is a conversation that draws interdisiciplinary marine researchers, particularly from the natural sciences, into a lateral dialogue with the social sciences and the environmental humanities on the practice of hybrid phenomenologies of the sea in order to push for more non-representional, de-centered and non-western centric explorations of oceanic relationalities and connections that prefigure a broader politics of life.

Coastal or Marine Lifeworlds? De-terrestrializing and Un-humanizing a Concept

The very notion of lifeworlds remains to be taken as an open-ended concept that is malleable enough to be creatively reworked and applied across multiple socio-environmental contexts. Yet phenomenologically-inspired lifeworlds research has traditionally privileged the study of terrestrially-bound themes. It can be argued that the problem lies with the humanistic social sciences that have been less forthcoming in putting lifeworlds out at sea.

When the role of the sea in imperial and colonial expansion came to be understood beginning in the fifteenth century, the ocean was still overwhelmingly and paradoxically perceived in Enlightenment scholarship as “a quintessential wilderness” (Mack, 2011, p. 17), an atemporal place and as cultural tabula rasa. As Emile Cocco writes (Cocco, 2013, p. 6), “the sociological ignorance of the sea is quite striking against the major role played by the maritime environment in literature, religion or philosophical thought” despite critical interventions made by philosophers such as G.W.F. Hegel who “celebrated the sea for its uttermost importance in the development of state, economy and European identity.”

Over at least the last three decades, coastal and historic geography, maritime anthropology, sociology and cartography have made significant conceptual and epistemological inroads to grounding and understanding the diversity of marine spaces and “peoples of the sea,” distinguished by everyday processes of sense-making and daily practices of cohabiting fluid waterworlds (see Acheson, 1981; Astuti, 1995; Steinberg, 2001; Cordell, 2007; van Ginkel, 2007; Peters, 2010). Seas and coastlines were therefore more than mere resource bases and sites of socio-economic extraction, value and exchange. Seascapes have been perceived as spaces of enskillment and ancestral belonging, as dreamscapes of danger and presence, and as sites of desire and dwelling, while practices such as voyaging and coasting have historically been interpreted in relational terms, that connected expansive networks of social groups and distant spaces (see Firth, 1946; McWilliam, 2003; D'Arcy, 2006, 2013; McCormack, 2007; Hau'ofa, 2008; Cohen, 2010; Lehman, 2013).

Mack (2011) argues that the majority of community-based research has been undertaken on coastal spaces, overwhelmingly focused on land-dwelling (and often gendered) social groups such as fisherfolk, traders, seamen, dockworkers, coastguards and surfers, for example (see Nieuwenhuys, 1994; Laderman, 2014). Yet a smaller corpus of research engages with liminal spaces, mariners and ship-based societies, from cruise liners to piracy networks and floating armories (see Rediker, 2004; Langewiesche, 2005; Gharibyan-Kefalloniti and Sims, 2012). Meanwhile the study of marine scientific research expeditions and commercial seabed mining ventures mark an exciting new turn in the study of floating societies and of underwater verticalities (see Helmreich, 2009; Steinberg and Peters, 2015).

Recent strands of interpretative marine research, particularly across the fields of cultural geography, anthropology and sociology have predominantly been concerned with two key, interlocking questions. The first concerns interrogations of how traditionally earth-bound, “land-locked” disciplines such as human geography and sociology, together with their very “grounded” methodologies (evidenced in terms such as fieldwork) could be put out to sea. As an increasing number of cultural geographers argue, the mere thematic expansion on marine topics and the study of the sea as a “different” space barely answers this rallying call; indeed, conscious efforts to start thinking “from the water” is required in order to “chart new representations, understandings and experiences of the sea, plotting water worlds that are more than a “perfect and absolute blank” (Anderson and Peters, 2014, p. 4). Yet in actuality, the disciplinary boundaries through which these conceptual and epistemological modes of understanding (and practice) unfold remain relatively less permeable, especially when marine-centered and land-based social and natural scientists continue to talk away from one another.

In part, these disciplinary gaps foreground the pressing need to “de-terrestrialize the Academy” (Hornidge, 2015). It draws attention to the urgency to foster deeper and more explorative efforts of putting into dialogue (as opposed to uncritically comparing) the diverse worlds of hinterland, coastal and marine-based societies, and their social-natural assemblages. Moreover, it seeks to question the very conceptual and methodological assumptions that have arguably favored terrestrially derived interpretations of reality. For example, as Mack (2011, p. 23) argues, much theory-work and empirical refocusing is needed in order to bring the study of seascapes to the same level of conceptual and methodological sophistication as the study of landscape geography or anthropology.

The second overarching conundrum rests on how expanding the many ways in which de-centered non-human-centric vantage points in studying seas, oceans and their manifold connectivities could be better explored. It comes as little surprise that the overwhelmingly humanistic hue of lifeworld theorizing in the past—best illustrated through what Kirksey and Helmreich (2010, p. 546) refer to as the paradox of human exceptionalism—that placed the (thinking-being) Anthropos at the center of its empirical inquiry. Inevitably the lifeworld then constituted a humanized gaze of the world, as evidenced in the case of anthropomorphized writings for example. Arguably the mere presence of the so-called “non-human” both lively and inanimate, in an epistemological sense, unwittingly came to be patterned around the figure of the human, and its broader material and symbolic implications for socio-political and economic life—invariably recast as food stock, tradable commodities, and land/seascape backdrops among others.

How then have more recent endeavors into delineating marine epistemologies taken shape? Moreover, what can be said of their inherent limitations, while reimagining more inclusive and hybrid templates implicating non-linear phenomenologies of the sea? Two distinct and inter-related thematic strands within inductive social science research stand to be taken as critical points of departure through which a lifeworlds approach could be potentially enlivened. The first entails a significant body of largely coastal ethnographic and historic research undertaken through the interpretive lens of “saltwater” realms, meanings and interactions (see Sharp, 2002; McNiven, 2004; Schneider, 2012). The second constitutes the lively and dynamically growing field of critical ocean geography that attempts to rupture, stimulate and experiment with novel ways of thinking and writing through/with (as opposed to on) “wet ontologies” (Steinberg and Peters, 2015), while weaving in both interspecies being and becomings, together with the material flows, processes and social lives of inanimate objects and previously understudied forms of lived dimensionality such as volume and marine verticality (see Anderson, 2012; Sammler and House-Peters, 2013; Muttenzer, 2015).

We first turn to phenomenologically-inspired work on saltwater realities and processes of sense-making. In the history of science, saltwater has been both a powerful substance as well as a metaphor to think with/through. As Helmreich (2011, p. 133) reminds us, the very blueness of seawater became a “matter of cultural construal, rather than of sheer empiricity” when invoking the famous proclamation made by the German anthropologist Franz Boaz.

In the contemporary context, marine realities referenced through saltwater networks and figurations—including people, places, the “non-human” (i.e., fish, waves, technologies) and their forms of interaction and movement, are seen through collectives such as the Australian indigenous Saltwater People Network (NAILSMA), and the Canadian grassroots fisher organization the Saltwater Network. Moreover, in scholarly writing, the inference to “saltwater people” (Sharp, 2002; McNiven, 2004) came to be synonymous with indigenity and aboriginal forms of socio-spatial mobility, knowing, and interacting across localized seas that were at the same time spiritscapes, imbued with maritime rituals and complex historiographies of their own.

Of late, varied sub-fields under the rubric of “salty geographies” have been gaining greater appeal among interpretative scholars particularly across Anglo-American and postcolonial contexts. In attending to translocal voices calling for the “historicization of the ocean”—not only does it aim to reflexively de-terrestrialise academic lenses through which multistanded histories and sociologies have been conventionally interpreted, but it also attempts to trouble the stability of geopolitical identities and the very temporalities under which they have been (re)made and naturalized. Once more, social-natural assemblages and meshworks have stood as dominant conceptual and epistemological frames with which to enliven hitherto understudied connectivities, agencies and socionatural-political dynamics not only between conventional outcasts, un/familiar figures and material spaces (e.g., buccaneers and wreckers, port harbors and littoral utopias), but also of questions around non-human presence, interaction and their transformations, a line of inquiry we will later revisit.

However, two important methodological limitations present themselves when figuratively and empirically conceptualizing the material-symbolic substance of saltwater worlds. The first shortcoming entails the problematic conflation of “saltwater” realms with notions of indigeneity. While significant advances within this body of literature have predominantly focused on postcolonial and decolonial aboriginal histories and interpretive framings, the specificity of this term arguably runs the risk of uncritically accepting a sense of “authentically” dwelling with the sea. Its conceptual framing potentially forecloses “non-traditional” sensibilities and practices that entail entire coastal (and marine) lifeworlds in their own right. Second, while seascapes themselves can be theoretically imagined as “a cosmologically totalizing” realm rather like terrestrial desertscapes (Siriwardane, 2015, p. 158), there emerges the tendency of essentializing or “othering” the sea as a world that is entirely detached from land-based sensibilities. As postcolonial geographers such as Connery (2006) posit, the ontological distanciation between land and sea is strongly suggestive of a Eurocentric imaginary. Furthermore, complex land-sea interactions inevitably determine how life is experienced and lived, for as Ingold (2000, p. 167) asserts, everyday perception formations are never passive processes, and are structured against frames of socio-environmental meaning-making. However, the ways in which land-sea distinctions are typified, typologized and taken for granted as objective reality (in a Schützian sense) may remain intensely differentiated. Thus, what is considered to be typically “of the sea” or “of the land” may be separately interpreted and lived, however it is important to bear in mind that since Bronislaw Malinowski's Argonauts (Malinowski, 1922) among others, anthropological writing reveal that the absolute spatio-cognitive separation between watery realms and the terra firma are barely universal (see Anderson and Peters, 2014, p. 8).

Another emergent field within interdisciplinary marine research is what could be broadly framed as “interspecies worldings,” if we were to more meaningfully reuse the term borrowed from the environmental humanities (see DeLoughrey, 2015). While engaging more productively with broader questions around human hubris, anthropocentricity, and of racialized universality particularly evident within highly politicized debates on the Anthropocene, through which it troubles notions of “both indigeneity as well as interspecies ontologies in an era of sea level rise that is catalyzing new oceanic imaginaries” (p. 352).

Having emerged at the crossroads of three interdisciplinary currents constituting environmental studies, animal studies, and Science and Technology Studies, multispecies ethnography (as a predecessor to interspecies theorizing) sought to bring a host of less visible and understudied organisms, from fungi to mollusks and oceanic microbes into anthropological conversations by virtue of acknowledging that they possessed “legibly biographical and politics lives of their own” Kirksey and Helmreich (2010, p. 545).

Epistemologically, this conceptualization departed from conventional ways of thinking about the non-human as object, and rather as bodies and substances habiting and co-constituting shared human social worlds. In plainer Schützian terms, such worlds are reversely peopled by more-than-human forms of life and inanimate objects positioned across subjectivities, spatialities and temporalities of worlds that are pre/past, contemporary and future (also see Viveiros de Castro, 2016, pp. 156–157). However, the means with which to draw out this relational ontology without unduly falling into the trap of anthropomorphism has always remained a challenge. The “more-than-human” was conceptually privileged over more deficit-centered “non-human” subjectivities. Second, it strove to explore diverse, multi-stranded and power-laden networks, assemblages and meshworks implicating more-than-human entanglements everyday life, which enlist not only animals, plants, and microorganisms, but also objects, technologies, knowledge forms, minerals, air, water, and energy flows for example. For example, Probyn (2013) in tracing people following fish, stories a complex figuration of how pelagic herrings, anchovies, sardines, local corporates, and Japanese universities co-produce internationally tradable tuna that she termed as a “more-than-human fish,” replete with its own individualized historic records that would put a contemporary biometric identity card to shame.

While a more comprehensive description of the generative trajectory through which multi/interspecies epistemologies developed goes beyond the scope of this paper, it is worth noting that the earliest scholars (including Donna Haraway, Paul Rabinow, Eduardo Kohn, and Anna Tsing among others) who have written on these relationalities have argued that human nature and living by default encompasses pluri-worlds (see Kirksey and Helmreich, 2010, pp. 549–548). Indeed, as decolonial scholars often posit, post-Enlightenment rationalities and hierarchies privileging mastery over Nature and concomitant narratives of stewardship have in turn historically muted these existential states (see Belcourt, 2015). While the conceptual fault lines between multi- and inter-species ethnography remain blurred, arguably the latter focuses on communicative worlds comprising multiplications of associations shaped through networks, events, circulations and other forms of encounter. Lively vocabularies, particularly in the overlapping disciplines of cultural geography and anthropology follow these interspecies (life)worldings, comprising for example Ingold and Pálsson's (2013) understandings of “biosocial becomings” and Latimer's (2013) notion of “being alongside” as opposed to “being with.”

Lifeworld-inspired sensibilities also offer nuanced understandings of powerful yet invisible materialities (and their performativities), like in the case of Robertson's (2014) study on island groundwater networks and flows in Kiribati and their multiple enactments. For others like Peters and Steinberg (2015), multi-sensory, corporeal and affective engagements with the sea (for example, salt on skin, the performativity of a recreational beach) calls to attention values of not just “thinking from the sea, but how we can think with the sea” and what this means in widening explorative horizons for understanding multiple modes of marine sense-making. As a start then, it would seem prudent to acknowledge that what these fluid ontologies spell are arguably less visible and cognitively less graspable dimensions such as volume, liminality/mobilities, the unruliness of depth, and of vertical territorializations for example (see Steinberg and Peters, 2015). Yet these multisensory and embodied forms of knowing can be further enriched critically by hybridizing older lifeworld readings for example Merleau-Ponty's being-with-the-world. To take this concept further would mean to use it in prefiguring traditional meanings of spatial and temporal depth. It would also warrant critical reflections on the limits to knowing and feeling, contemplated through what Mazis (2010, p. 123) eloquently puts as “the further displacement of the human into the world's play of becoming.”

These conceptual and epistemological currents have further crisscrossed with the recent turn toward non-representational ethnography, particularly within the disciplines of human geography, anthropology and sociology (see Thrift, 2008). Not only does it emphasize the tracing of more-than-human relations, but pays attention to the very events, practices, socio- and pre-cognitive structures of feelings, mobilities, including the extra-textual and “non-discursive dimensions of spatially and temporally complex lifeworlds” that have otherwise stood concealed by conventional ethnographic styles that have “been in the habit of uncovering meanings and values that apparently await our discovery” (Vannini, 2014, pp. 1–2). In this context, embodied actions and movements themselves speak and enact, rather like the surfed waves that people allude to as watery “places” that conjoin together (Anderson, 2012).

At first glance, it may appear that conventional phenomenological-lifeworlds research has little to lend an open-ended and experimental epistemology, particularly one that has little to embellish in terms of drawing forth externalized meanings in order to render any objective explanation. Yet upon closer inspection, the very experientialist spirit that is warranted of immersive lifeworlds research (see Jackson, 2012) beckons what a non-representational ethnographic journey would entail, not in the least self-reflexivity. The experimental becomes the experiential and vice versa, making for a compelling case for critical conversations and border crossings between relational concepts cleaved within contemporary cultural geographies and anthropologies on the one hand, with neo-classical theorizings and operationalizations of the multi-stranded concept of the phenomenological-lifeworld.

Conclusion

We argue for a more conscious engagement with the concept and diverse epistemological foundations of lifeworlds (Ger. Lebenswelten) in interdisciplinary coastal and marine research. Our discussion serves as an open invitation for interdisciplinary scholars to more critically reflect the advantages together with the shortcomings of diverse lifeworlds conceptualizations. At the same time, we reiterate the double bind that contemporary phenomenological praxis finds itself in. On the one hand, the philosophical complexity and the diverse epistemological foundations of lifeworlds theorizing make its entry into present-day interdisciplinary research relatively more challenging. On the other hand, the apparent paucity of perceptions-based research on marine-centric/specific knowledges and the experience of everyday life makes for an urgent case for the integration of lifeworlds approaches. Eventually, it is the attempt to free the lifeworlds concept from a singularly land-based lens that makes further research into marine-based phenomenology far more appealing and pressing at the same time. How then, could the endeavor for embarking on lifeworlds research across multiple coastal and marine realms, possibly begin?

Epistemologically, this multi-stranded concept opens up reflective spaces through which we, as interdisciplinary researchers, could unpack experiences and meanings around our own positionality. Methodological processes such as bridling offer practical techniques through which to consciously suspend judgment and explore biases and assumptions that are implicit to our own lifeworlds. Through two illustrative case studies on diverse waterworlds, we have shown how surface level perceptions-based research may still run the risk of perpetuating subjective assumptions often taken as constituting “objective” reality.

Conceptually, we reveal how the integration of a specific lifeworlds approach within interdisciplinary work warrants active reflection, depending on the research puzzle or question that it seeks to understand. Empirical community-based fieldwork is hardly a process that entails passive encounters between “subjects,” sets of data, and their forms of knowledge generation. While it offers little recourse to meta-level analysis, it provides the means to detangle fine-grained nuances across multiple and locally-situated realities that are often regarded as being “messy,” encompassing values, norms, worldviews and actions that may often sit in contradiction to each other. While the concept affords the space through which to study the complexities, ambiguities and ambivalences inherent across both land- and sea-based societies, it further promises the means through which to sidestep over-simplistic and essentialist inferences to the vague and embattled notion of “culture.”

Methodologically, while the concept favors the study of an individual's interpretation as the primary unit of analysis, it provides varied empirical layers through which implicit meanings could be drawn to the surface. Abstractions of course are never entirely static nor complete, in similar ways that knowledge(s) and forms of knowing are constantly in flux. Having problematized the endeavor of: (a) “reading the world” through categories of knowing (e.g., beliefs, mental maps), (b) of being and becoming (e.g., identities, material movements, flows); (c) of multiple socialities (e.g., more-than-human assemblages), and; (d) through experience (e.g., events, routinized social practices), the methodological foundations of the lifeworld enable us to work with concretely situated frames that people use to guide as well as to challenge perceptions and behavior.

The lifeworld approach presents an empirical frame and an integrative research agenda through which diverse modes of dwelling with, and working the sea could be investigated, transcending a vast body of work related to coastal communities and spaces. Several thematic vantage points stand to be taken as points of departure in enlivening deeper forays into “marine lifeworlds.” Rather than merely deliberating on surface-level perceptions, the lifeworld enables us to think beyond them. Novel and hybrid approaches to understanding marine epistemologies/forms of knowing would therefore require an ongoing engagement with how varied conceptual strands, methodological devices and thematic foci could be reworked in creative ways in order to consciously unhinge the concept from its terrestrially-bound roots, which at the same time naturalize the nature-cultural binary.

Thus, thinking through place-based and materially interpreted realms such as saltwater-worlds and their manifold socialites and interactive entanglements which in turn solicit new ways of thinking, feeling and writing with/alongside oceans and seascapes (i.e., wet/fluid ontologies and interspecies worldings) are but an open-ended starting point. Attempts at integrating and tracing dynamic flows of lifeworld matter, relationships and symbolic meanings and events—from fish and oceanic currents to in/visible material flows and events that are constitutive of everyday life—opens up fertile ground and exciting imaginative possibilities with which to launch an inductively-shaped concept out to sea.

Author Contributions

All persons who meet authorship criteria are listed as authors, and all authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. Furthermore, each author certifies that this material or similar material has not been and will not be submitted to or published in any other publication. RS: Conception or design of the work; Manuscript drafting and critical revision of the article. AH: Critical input on the article.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Ryan McAndrews, Edward Jeremy Hind and Jan Maarten Bavinck for their insightful comments on previous drafts of this paper.

References

Acheson, J. (1981). Anthropology of fishing. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 10, 275–316. doi: 10.1146/annurev.an.10.100181.001423

Anderson, J. (2012). Relational places: the surfed wave as assemblage and convergence. Environ. Plann. Soc. Space 30, 570–587. doi: 10.1068/d17910

Anderson, J., and Peters, K. (2014). “A perfect and absolute blank: human geographies of water worlds,” in Water Worlds: Human Geographies of the Ocean, eds J. Anderson and K. Peters (Surrey; Burlington, VT: Ashgate), 3–17.

Astuti, R. (1995). People of the Sea: Identity and Descent among the Vezo of Madagascar. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Belcourt, B.-R. (2015). Animal bodies, colonial subjects: (Re)Locating animality in decolonial thought. Societies 5, 1–11. doi: 10.3390/soc5010001

Bengtsson, J. (2013). With the lifeworld as ground. A research approach for empirical research in education - the Gothenburg tradition. Indo Pacific J. Phenomenol. 13, 1–18. doi: 10.2989/IPJP.2013.13.2.4.1178

Berger, P., and Luckmann, T. (1967). The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. Hardmonsworth: Penguin.

Busby, C. (2000). The Performance of Gender: An Anthropology of Everyday Life in a South Indian Fishing Village. London; New Brunswick, NJ: Athlone Press.

Connery, C. (2006). There was no more sea: the supersession of the ocean, from the bible to cyberspace. J. Hist. Geogr. 32, 494–511. doi: 10.1016/j.jhg.2005.10.005

Cordell, J. (2007). A Sea of Dreams: Valuing Culture in Marine Conservation. Berkeley, CA: Ethnographic Institute.

D'Arcy, P. (2006). People of the Sea: Environment, Identity, and History of Oceania. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawai'i Press.

D'Arcy, P. (2013). “Sea worlds: Pacific and South-East Asian History Centred on the Philippines,” in Oceans Connect: Reflections on Water Worlds Across Time and Space, ed R. Mukherjee (Delhi: Primus Books), 23–39.

Dahlberg, K., Drew, N., and Nyström, M. (2008). Reflective Lifeworld Research. Lund: Studentlitteratur AB.

Das, V. (2006). Life and Words: Violence and the Descent into the Ordinary. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

DeLoughrey, E. (2015). “Ordinary futures: interspecies worldings in the Anthropocene,” in Global Ecologies and the Environmental Humanities: Postcolonial Approaches, eds E. DeLoughrey, J. Didur, and A. Carrigan (New York, NY; Oxford: Routledge), 352–372.

Ehrich, L. (2005). “Revisiting phenomenology: its potential for management research,” in Challenges or Organisations in Global Markets, British Academy of Management Conference (Oxford: Said Business School, University of Oxford), 1–13.

Finlay, L. (2013). Unfolding the phenomenological research process: iterative stages of “seeing afresh.” J. Human. Psychol. 53, 172–201. doi: 10.1177/0022167812453877

Gharibyan-Kefalloniti, N., and Sims, D. (2012). Relational aesthetics and emotional relations: leadership on board merchant marine ships. Organ. Manag. J. 9, 179–186. doi: 10.1080/15416518.2012.708852

Habermas, J. (1984). Theory of Communicative Action, Volume One: Reason and the Rationalization of Society. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Helmreich, S. (2009). Alien Ocean: Anthropological Voyages in Microbial Seas, Berkeley, CA; Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

Helmreich, S. (2011). Nature/culture/seawater. Am. Anthropol. 113, 132–144. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1433.2010.01311.x

Hornidge, A.-K. (2015). “Transformative research beyond the marine-terrestrial divide,” in Keynote at Euromarine Foresight Symposium ‘FutureCoast Europe.’

Hultgren, F. (1995). The phenomenology of “doing” phenomenology: the experience of teaching and learning together. Hum. Stud. 18, 371–388. doi: 10.1007/BF01318618

Husserl, E. (1970). The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press (originally published in 1939).

Ingold, T. (2000). The Perception of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London; New York, NY: Routledge.

Ingold, T., and Pálsson, G. (2013). Biosocial Becomings: Integrating Social and Biological Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jackson, M. (2012). Lifeworlds: Essays in Existential Anthropology. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Johansson, E., and Emilson, A. (2010). Toddlers' life in Swedish preschool. Int. J. Early Child. 42, 165–179. doi: 10.1007/s13158-010-0017-3

Johansson, K., Ekebergh, M., and Dalhberg, K. (2008). A lifeworld phenomenological study of the experience of falling ill with diabetes. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 46, 2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.09.001

Kirksey, S. E., and Helmreich, S. (2010). The emergence of multispecies ethnography. Cult. Anthropol. 25, 545–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1360.2010.01069.x

Kohn, E. (2013). How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Laderman, S. (2014). Empire in Waves: A Political History of Surfing. Berkeley, CA: university of California Press.

Langewiesche, W. (2005). The Outlaw Sea: A World of Freedom, Chaos, and Crime. New York, NY: North Point Press.

Latimer, J. (2013). Being alongside: rethinking relations amongst different kinds. Theory Cult. Soc. 30, 77–104. doi: 10.1177/0263276413500078

Lehman, J. (2013). Relating to the sea: enlivening the ocean as an actor in eastern Sri Lanka. Environ. Plann. D Soc. Space 31, 485–501. doi: 10.1068/d24010

Lynch, M. (2000). Against reflexivity as an academic virtue and source of priviledged knowledge. Theory Cult. Soc. 17, 26–54. doi: 10.1177/02632760022051202

Madsen, P. (2002). “Introduction,” in The Urban Lifeworld: Formation, Perception, Representation, eds P. Madsen and R. Plunz (London; New York, NY: Routledge), 1–21.

Malinowski, B. (1922). Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagos of Melanesian New Guinea, London: Routledge & Sons.

March, J. G., and Olsen, J. P. (2005). Elaborating the “New Institutionalism.” Oslo: University of Oslo Centre for European Studies Working Paper No. 11.

Mazis, G. A. (2010). “Time at the depth of the World,” in Merleau-Ponty at the Limits of Art, Religion, and Perception, eds K. Semonovitch and N. DeRoo (London; New York, NY: Continuum), 120–146.

McCormack, F. (2007). Moral economy and Maori fisheries. Sites J. Soc. Anthropol. Cult. Stud. 4, 45–69. doi: 10.11157/sites-vol4iss1id27

McNiven, I. (2004). Saltwater people: spiritscapes, marine rituals and the archeology of Australian indigenous seascapes. World Archeol. 35, 329–349. doi: 10.1080/0043824042000185757

McWilliam, A. (2003). Timorese seascapes: perspectives on customary marine tenures in East Timor. Asia Pacific J. Anthropol. 3, 6–32. doi: 10.1080/14442210210001706266

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1981). Phenomenology of perception. London: Routledge & Kegal Paul (originally published in 1945).

Muttenzer, F. (2015). The social life of sea-cucumbers in Madagascar: Migrant fishers' household objects and display of a marine ethos. Etnofoor 27, 101–121.

Nieuwenhuys, O. (1994). Children's Lifeworlds: Gender, Welfare and Labour in the Developing World. New York, NY: Routledge.

Oberkircher, L., and Hornidge, A.-K. (2011). Water is life – farmer rationales and water saving in Khorezm, Uzbekistan: a lifeworld analysis. Rural Sociol. 76, 394–421. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-0831.2011.00054.x

Pálsson, G. (2000). “Finding One's Sea Legs: learning the process of enskilment, and integrating fisheries and their knowledge into fisheries science and management,” in Finding One's Sea Legs: Linking Fishery People and Their Knowledge with Science and Management, eds B. Neis and L. F. Felt (St. John's, NL: ISER), 26–41.

Peters, K. (2010). Future promises for contemporary social and cultural geographies of the sea. Geogr. Compass 4, 1260–1272. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-8198.2010.00372.x

Peters, K., and Steinberg, P. (2015). “A Wet World: rethinking place, territory and time,” in presented at the Annual Association of American Geographers (AAG) Conference (Chicago, IL). Available online at: https://societyandspace.com/material/article-extras/a-wet-world-rethinking-place-territory-and-time-kimberley-peters-and-philip-steinberg/ (Accessed August 3, 2016).

Pohl, C., and Hadorn, G. H. (2007). Principles for Designing Transdisciplinary Research. Munich: Oekom Verlag.

Probyn, E. (2013). Women following fish in a more-than-human world. Gender Place Culture 21, 589–603. doi: 10.1080/0966369X.2013.810597

Rediker, M. (2004). Villains of All Nations: Atlantic Pirates in the Golden Age. London; New York, NY: Verso.

Ricoeur, P. (1974). The Conflict of Interpretations: Essays in Hermeneutics. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press (originally published in 1969).

Robertson, M. L. B. (2014). “Enacting groundwaters in Tarawa, kiribati: searching for facts and articulating concerns,” in Water Worlds: Human Geographies of the Ocean, eds J. Anderson and K. Peters (Surrey and Burlington, NC: Ashgate), 141–161.

Roth, W.-M. (2004). Cognitive phenomenology: marriage of phenomenology and cognitive science. Forum 5:3. Available online at: http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/570/1237

Sammler, K. G., and House-Peters, L. (2013). Tracing LA's Marine Topographies: Climate, Currents, and Calamari, Vol. 48. Association of American Geographers Newsletter. Available online at: http://www.aag.org/cs/news_detail?pressr (Accessed August 08, 2016).

Schneider, K. (2012). Saltwater Sociality: A Melanesian Island Ethnography. New York, NY; Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Schütz, A. (1960). The Phenomenology of the Social World. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Siriwardane, R. (2015). ‘Sambandam’: Cooperation, Contestation, and Coastal Lifeworlds in Postwar Sri Lanka. Doctoral dissertation. University of Bonn, Bonn.

Steinberg, P. E. (2001). The Social Construction of the Ocean. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Steinberg, P., and Peters, K. (2015). Wet ontologies, fluid spaces: giving depth to volume through oceanic thinking. Environ. Plann. D Soc. Space 33, 247–264. doi: 10.1068/d14148p

Thrift, N. (2008). Non-Representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect, Oxford; New York, NY: Routledge.

van Ginkel, R. (2007). Coastal Cultures: An Anthropology of Fishing and Whaling Traditions. Apeldoorn; Antwepen: Spinhuis Publishers.

Vannini, P. (2014). Non-representational ethnography: new ways of animating lifeworlds. Cult. Geograph. 22, 317–327. doi: 10.1177/1474474014555657

Viveiros de Castro, E. (2016). The Relative Native: Essays on Indigenous Conceptual Worlds. Chicago, IL: Hau Books

Weeratunge, N. (2009). “Living in the wind: Gendered perceptions of poverty and well-being in fisheries communities in Sri Lanka,” in Paper Presented at the MARE Conference on ‘Living with Uncertainty and Adapting to Change’ (Amsterdam).

Keywords: lifeworlds, meaning making, applied phenomenology, marine epistemologies, seascapes

Citation: Siriwardane-de Zoysa R and Hornidge A-K (2016) Putting Lifeworlds at Sea: Studying Meaning-Making in Marine Research. Front. Mar. Sci. 3:197. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2016.00197

Received: 10 May 2016; Accepted: 26 September 2016;

Published: 08 November 2016.

Edited by:

Wen-Cheng Wang, National Taiwan Normal University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Edward Jeremy Hind, Manchester Metropolitan University, UKJan Maarten Bavinck, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands

Copyright © 2016 Siriwardane-de Zoysa and Hornidge. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Rapti Siriwardane-de Zoysa, rapti.siriwardane@leibniz-zmt.de

Rapti Siriwardane-de Zoysa

Rapti Siriwardane-de Zoysa Anna-Katharina Hornidge1,2

Anna-Katharina Hornidge1,2