From Face-To-Face to the Online Space: The Continued Relevance of Connecting Students With Each Other and Their Learning Post COVID-19

- 1School of Education, University of New England, Armidale, NSW, Australia

- 2School of Education, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW, Australia

At the time of writing, the largest state in Australia is once more in full lockdown because of surging cases from the new variant strain of COVID-19. During the last lockdown in early 2020, we conducted a study analyzing the efficacy of mapping best-practice face-to-face university teaching into the online space. This article reports on the results of a survey from the perspective of student belonging. Isolation was the most prevalent theme recorded by students despite not being one of the research questions asked. The importance of adopting the model in online university courses in the current/post-COVID-19 world is presented.

Introduction

When in early 2020, the outbreak of COVID 19 required universities to deliver teaching online, lecturers were faced with the significant challenges to hurriedly transition to various learning management system platforms. The move to online delivery was considered by many providers to merely be a translation of recording existing face-to-face presentations in powerpoint and upload these presentations into a online delivery platform. This approach can been described as “emergency remote teaching” (Hodges et al., 2020, p. 3), and should not be under a misconception that it is online learning. Online learning design and its related nine moderating variables has been clearly articulated by Means et al. (2014) and highlights an ecosystem of learner support in relation to modality, pacing, student-lecturer ratio, pedagogy, lecturer and student role, communication, assessment and feedback.

In contrast, the push to transition online provided an opportunity to develop a course that met the criteria of an online learning design. The result was the development of a model on which we based an online course that sits within a postgraduate degree (Page and Garrad, 2021). This article shows the results of research conducted on student perceptions of learning within the course, where the authors examined the impact of the design restructure. The results indicated that students found the most helpful pedagogical approaches were those that assisted with minimizing isolation. This somewhat unexpected finding arose from the changing context of the university educational experience. Therefore, this article will consider the relevance of addressing how an online course structure can positively impact on students’ experiences of belonging. In doing so, we will use an adaptation of the Three Spaces of Belonging theoretical framework (Baroutsis and Mills, 2018) to analyze and discuss the results of the research findings. The implications for future use of an online model (Virtual Teams Model within the ACAD Framework) to speak to student belonging in online university courses within a current/post-COVID-19 world are also discussed.

Virtual Teams Model Within the ACAD Framework

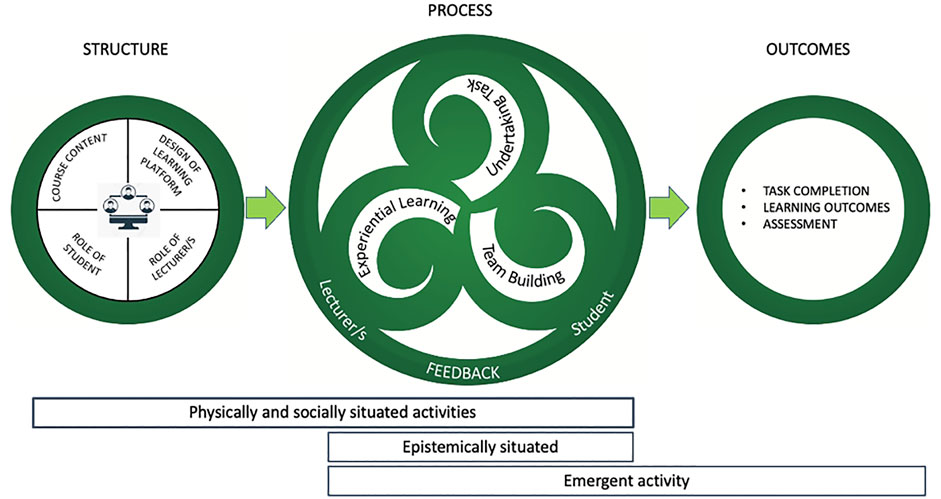

Virtual Teams is a term that indicates a group of people who work together, where often they are located in different geographical settings and use a variety of technological tools in the collaborative efforts to achieve a shared goal (O’Duinn, 2018). The use of the Virtual Teams approach was used to embed the pedagogy of working in groups in online learning. The reason this was regarded as necessary was that in order to meet the needs of learners, the university could not merely shift face-to-face content to an online interface. There was also the additional need to cater for 21st century teaching and learning. To become effective learners in any contemporary learning environment, students need to be problem-solvers, critical thinkers and be able to work in groups using digital resources (Yoon and Gruba, 2017; Stephenson, 2018; Benade, 2019). Carvalho and Yeoman. (2018) was initially designed for face-to-face teaching and learning to guide the principles of 21st century pedagogy and was then adapted embedding virtual teams to manage the difference between delivery modes. Using this Framework, we were able to map the components of a physical and socially situated design of the course, addressing epistemically concepts where emerging co-creation and co-configuration of learning occurred. We chose to use this framework as it connected the space and practice of contemporary pedagogy that could be mapped into the online context. The Virtual Teams Model within the ACAD Framework then steered the design of the online course.

Specifically, the model describes three areas of teaching and learning, and these are structure, process and outcomes.

Structure

Attention to structure includes the organization of course content that accounts for the relevance of material as well as the delivery of that material using multiple modes, such as video, text, readings (Yoon and Gruba, 2017; Stephenson, 2018). Further, within the structure, the role of the student should be carefully communicated which includes setting clear expectations. The role of the lecturer also needs to be well-defined, as the role will shift to facilitation rather than as a disseminator of information. This notion supports Prosser and Trigwell, (2000) understanding of the relationship between teaching and learning which they report to be of more benefit when these constructs are aligned. The course structure also requires consideration of the design of the learning platform, where mapping into an online platform involves deliberations such as the visual design of the online site itself as well as the use of technological platforms that are possible within it (Hu, 2015).

Process

Process considerations include the addition of experiential learning opportunities in the course that also enable learning through reflection (Felicia, 2011). Team building is a further necessary aspect of the course process and thought needs to be given to develop collaboration skills and establish processes to counter any difficulties students might encounter within their teams. Moreover, Process also needs to take into consideration how students undertake tasks. As tasks are co-created and co-configured activities, this requires teams to construct and share a project plan in order to direct the project’s completion (Leal-Rodríguez and Albort-Morant, 2019). Finally, ongoing lecturer/student feedback is recommended as a necessary component within course design as it provides opportunities for students to engage with consistent formative feedback within the process cycle and to provide assurances of the fairness of the team process (Wiggins, 2012).

Outcomes

Outcome designs include task completion group co-constructivist collaboration activities. It is relevant to note that task completion can easily be overlooked in design, where task completion fails to align with the learning outcomes (Goodyear et al., 2018). The final concern of the Outcome process is to ensure that students understand the value and purpose of assessments and the role of the product (Aritz et al., 2017). This can be achieved by facilitating assessments that reflect “real-life” opportunities that students engage with (Iannone and Simpson, 2017).

Sense of Belonging

Belonging, or social identity, is how we define ourselves and characterise the group in which we belong (Hauge, 2007). A sense of belonging can be understood within students’ perception of being valued and respected by other students and by the university (Mulrooney and Kelly, 2020). Students who feel a sense of belonging to the university state that they are part of the community, and are recognized and accepted for their capabilities (van Gijn-Grosvenor and Huisman, 2020).

One of the challenges in accommodating a sense of belonging is the online platform itself, where a contrast exists between what face to face arrangements can provide that encourages a sense of belonging. Relationships are inherent in the development of a sense of belonging and to secure an identity as a learner (Kahu and Nelson, 2018). The physical space of a university campus offers students opportunities to meet face to face and to develop and strengthen their respective relationships both between students and between students and academic staff (Samura, 2018). Surroundings were profoundly altered because of lockdown, and student-teacher as well as student-student relationships in an online environment are now greatly different from that offered on campus. The shift to online spaces presents lecturers with an unexpected challenge of recreating some form of connectedness with students if they students are to maximize their learning experience.

The Benefits of Fostering Belonging

Having a sense of belonging is connected with student achievement and motivation and positive relationships with student success has also been empirically established (Knekta et al., 2020). For example, a sense of belonging has been associated with academic achievement (Abdollahi and Noltemeyer, 2018), retention (Han et al., 2017) and persistence (Lewis et al., 2017). To have a sense of belonging has been shown to be particularly important for marginalized groups such as students with a disability (Moriña, 2019) and students with low socio-economic status (Ahn and Davis, 2020b).

Within the university, belonging is recognized as multi-dimensional and has been described to include four dimensions: social and academic engagement, surroundings and personal space (Ahn and Davis, 2020a). Ahn and Davis. (2020a) study strongly and consistently reported that social engagement was the most noticeable or important factor, while academic engagement was also regarded to be significant by students. Additionally, the study identified two other themes and they were surroundings (geographic location, natural environment, living and cultural space) and personal space (self-identity, self-esteem, life satisfaction). The findings suggest that belonging is a complex multi-dimensional phenomenon and that universities, in support student belonging, need to account for all four factors.

Assessing the assumption that social connectedness and friendships are important to foster a sense of belonging in Australian universities, studies conducted in the southern state of Victoria examined the effect of social events and activities on students’ sense of belonging (Araújo et al., 2014). The research engaged first year students in various activities (for example, off-campus trips, in-class discussions and non-assessed tasks, and an on-campus exhibition event). Araújo et al. (2014) concluded that the actions listed enabled students to develop a strong sense of belonging. Building on these findings, the study was expanded to involve a university-wide approach. Students were again asked to rate the importance of student and campus-based activities and experiences. The findings showed 84% of students agreed that feeling respected or valued for their contribution in class was somewhat to extremely important in developing a sense of belonging. Other aspects regarded as important to fostering a sense of belonging included a feeling of fitting in with others and being counted by the institution.

Belonging in the Online Learning Space

Fostering a sense of belonging is seen as essential by many researchers, regardless of the learning environment, although literature exploring a sense of belonging and online learning continues to be limited (Peacock et al., 2020).

Peacock and Cowan (2019), using an adapted version of the community inquiry framework (Garrison, 2011) to scaffold action to nurture online learners’ sense of belonging, found that dialogue in social, cognitive and lecturer spaces contributed to an improved sense of belonging in students. Thomas and Herbert (2014) analyzed the lecturer and student experience of online learning and sense of belonging, stressing the importance of robust dialogue in that it fosters “a sense of camaraderie that diffuse[s] some of the isolation” (p. 76) that might be experienced in online learning. Healthy reciprocal communication, they suggest, impacts on learning by reducing anxiety, helping learners to develop new ideas, and building connections. In contrast, the lack of social networks hinders the development of belonging. It is also realized that fostering a sense of belonging and encouraging learners to engage in communities of practice is a challenge for lecturers in the online environment (Thomas and Herbert, 2014).

Peacock et al. (2020) responded to the gap in the limited literature in online learning and belonging. Their research reported three important themes that promoted a sense of belonging. These themes were interaction and engagement, a culture of learning, and the presence of support. The concept of engagement was related to lecturers and students. Lecturers were reported as being pivotal to the development of students’ sense of belonging, with comments such as “[lecturers] are the glue that bring it together” (p. 25). Engagement between students was facilitated by providing students opportunities to get to know each other before interacting with group tasks. A culture of learning emerged from reports that impacted positively or negatively on a student’s sense of belonging. Examples were cited as how the module was structured, the behavior of the lecturer, the materials, and how consequent student behaviors were responded to. The final theme derived from notions of support. Levels of support such as sharing of issues, being offered advice and views on aspects of the course, course design, and family support.

Theoretical Framework: The “Spaces of Belonging” Framework

Belonging in this article is viewed as the sociocultural connections that create ties to education spaces. Using spatial theory that makes sense of belonging in flexible learning spaces, we can consider how belonging is constructed through the different elements of space and how spatial elements can be developed and maintained belonging.

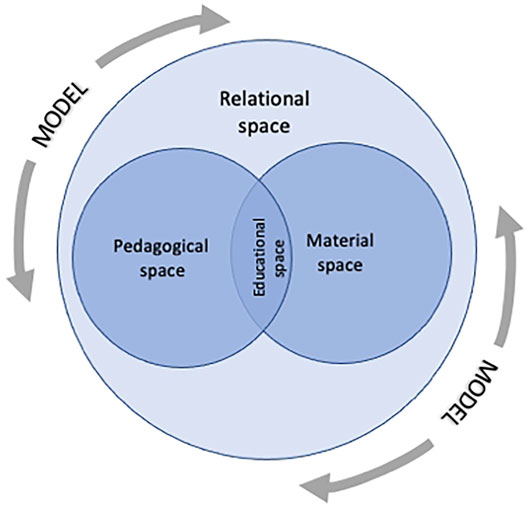

Baroutsis and Mills (2018) have characterized three elements that relate to belonging: relational, material, and pedagogical spaces that are associated with practices in education that are based on choice, shared respect and support. These spaces intersect to form the educational space: enabling and conversely disabling belonging, engagement, and connectedness within the setting. We will describe the characteristics of the spaces in the context of higher education. The first of the three spaces of belonging are relational spaces.

Relational Spaces

Space is an active mechanism that is created from a “complex web of relations” (Massey, 2013, p. 265). Relational spaces support and encourage social and emotional interactions between students (Baroutsis and Mills, 2018). The term “family” is often used by students when they describe relational space (te Riele, 2018, p. 252). If interactions include others that make them feel like they belong, then the space can be considered supportive and safe (Hooks, 2008). Practices within relational spaces promote a commitment to the overall group and to relationships within all members. Online social spaces have been used by students for some time (Cheung et al., 2011) and this “intentional social action” 1) facilitates a sense of connectedness and can be provided privately within existing learning management systems, or, more commonly, are developed by students themselves (e.g., Facebook). The facilitation in design for social spaces, both private and public, can create a sense of belonging and positively impact on learning. It allows also, for the development of learning strategies that are particularly relevant given the shift to active and group-orientated learning approaches (Chatti et al., 2007).

Material Spaces

Bessant, (2018) refers to material spaces as physical forms of space, where social formations are produced and re-produced. Design practices promote a sense of belonging and connectedness. When online learning is configured in traditional ways, this may limit the affordances of the space. For example, when forms of traditional transmission such as pre-recorded powerpoint lectures are uploaded to the site, this does not allow for relationships to be created.

Daniels et al. (2017), argue that decisions about design and place can enhance or restrict a sense of belonging. When educational spaces are configured in a non-contested way, they can become environments that lend themselves to different social practices of teaching and learning and allow different interactions between those working in spaces. Spaces therefore, can be used to allow people to feel in control of their learning if designed to support equity (Leigh, 2019).

Physically, online learning lends itself to isolation (Chametzky, 2021). Attempts to combat isolation can be made by addressing configurations of the platform where the material might alienate some. The design needs to be welcoming and interesting and accessible. Students who struggle with understanding how to navigate the platform and access material therefore, are more likely to feel disengaged and distracted from learning (Gillett-Swan, 2017).

As a resource for belonging, material space can impact on how easily it is to meet the same people (te Riele, 2018). Therefore, material/physical spaces that are designed to enable the development of group identity within small group membership will assist belonging.

Pedagogical Spaces

Pedagogical spaces that develop a sense of belonging are created from the design of, for example collaborative practices where students feel that they are part of the community, and recognized for their abilities (Colón García, 2017). Traditional pedagogical spaces in contrast, typically characterized as one teacher, single cell delivery of teaching, serve to disconnect the students from the lecturer and from each other (Byers et al., 2018). When choice and meaning are provided for learners, and students attach and share their learning with real-life experiences, then deep connections are made between students and their learning and belonging as a learner (te Riele, 2018).

Educational Spaces

Finally, we will discuss the space that is created in the intersection of relational, material, and pedagogical space. Characteristically, educational space is often seen as “a container within which education simply takes (its) place, with varying degrees of effectiveness and efficiency” (Green and Letts, 2007, 57), instead of understanding the interplay of structures and environments that might occur. The knowledge that is formed within this university space might consist of attitudes and ideas that relate to how educational institutions may operate, and the role and identity of schools within universities. Here, alternative educational spaces are created, such as the construction of a learning space of belonging that is inclusive of all learners and unpacks boundaries that separate “teacher and student’ or, in other words, “them and us” (Baroutsis and Mills, 2018).

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited through their engagement as students enrolled in the course at the University of Newcastle, New South Wales, Australia during Semester 1, 2020. Most of the student cohort were in-service teachers. Ethical approval was provided by the ethics committee at the university before undertaking research and informed consent was obtained by participants. Participants were invited to undertake an online survey using Qualtrics, (2019) at the completion of their course studies through an embedded link within the learning management system. Participants were asked to rate a series of questions from very helpful to not helpful (4 points scale) that evaluated the learning approach in the online learning space. A total of 67 surveys from a cohort total number of 180 were submitted and 24 records removed prior to data analysis because of being incomplete. This equated to a 37% response rate, and in educational contexts, lies within the average level of returned responses (Holbrook et al., 2007).

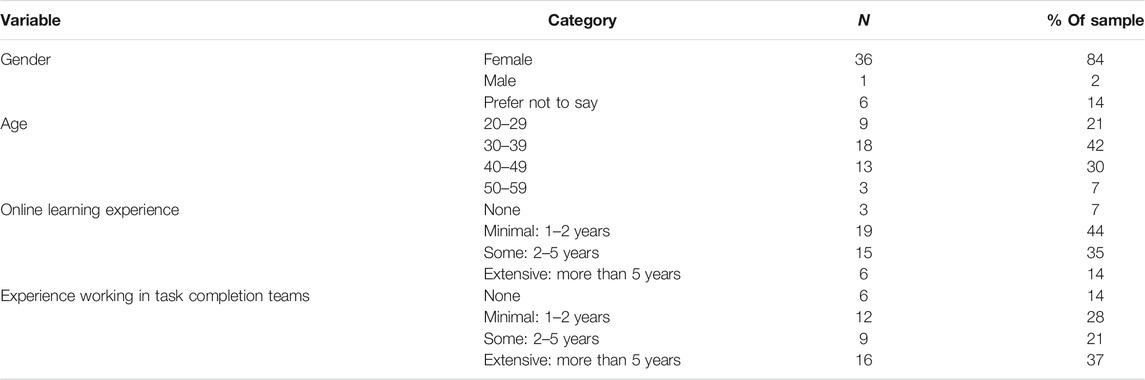

Participants were mostly female (84%) with 2% indicating they were male. Interestingly, 14% of respondents preferred not to report on their gender. Participants’ reported age ranges indicated that most were between 30 and 49 years of age, which represented 72% of the sample cohort. In addition, only six respondents (14%) reported having no experience in working in teams as a means of task completion at the tertiary education level. This is followed by 12 participants with minimal experience working in teams, with most of the sample (58%) indicating they had an experience of group work for a minimum of at least 2 years. 37% of respondents indicated they had extensive experience of working in groups of 5 years or more (see Table 1 for demographic data).

A. Do you have any comment about the benefit you found with these learning tools or features?

B. Do you have any comment about the challenges with these tools or features?

While the overarching research question of the study asked In what ways if any, was the design using the Virtual Teams model helpful as a learning tool or feature during an online university course? this article draws on a subset of that data which focuses on students reports of belonging as a result of responding to the qualitative questions in the survey. These questions were:

Data Analysis

Qualitative feedback collected within the survey was encoded through NVivo to identified key themes. From the initial data analysis, a key theme of isolation was identified, even though this topic was not asked in the research question. Subsequently, this theme was then explored in greater depth, looking for sub-themes.

Thematic Data Analysis

Qualitative feedback was collected from open-ended questions within the survey asking participants to comment on the benefits and challenges they found with the learning tools or features. The results were coded through NVivo (QSR International, 2020) to identify the key theme outlined within the model that related to isolation.

Both deductive and inductive reasoning was used through a thematic analysis approach, which considered themes based on the literature and the resultant interview data. The responses were analyzed, and grouped using the thematic analysis approach based on the recommendations of Braun and Clarke (2008) and Guest et al. (2012).

Results

A coding theme of isolation as impacted by COVID-19 was explored to address the concerns of learners during the pandemic. The theme was coded into subthemes that were clustered according to relational, material, and pedagogical space. The results are reported in relation to these clusters.

Relational Space

In their open-ended question responses students consistently reported the value of group work. It was commonly reported as a beneficial feature of the course. Relationships mattered, and students described being with others within their group was important, especially since the closure of the campus. One student for example reported that “contributing and working as a group is something I truly miss about university on campus and this gave us a chance to have that”.

Many reported being surprised how well the group engaged with each other and that the experience was a successful one: “We worked efficiently and effectively. I was surprised and fortunate to have a supportive, professional and helpful and cooperative group. The whole experience has been a positive interaction”. Another stated, “I am grateful to have had this group, they were easy and hard-working. I was surprised as I thought online group work would be awful and it wasn’t”.

Several described feeling lucky, fortunate, and even proud of their group: “I feel lucky to have had the opportunity to work with my team”; “I feel lucky to work with such strong intelligent group” and “I am very proud of my group and how we worked together”. These positive statements that connected students with their group were evident in statements that also described how students encouraged and motivated each other as a result such as one student who reported, “I was initially hesitant and anxious about working in a group online and then found that were we equally hard working and encouraged each other” and another who commented that “together we maintained motivation”.

Some reported the importance of being able to feel supported that did not rely on the teacher such as one student who said: “together we nutted it out”. Similarly, another commented that “my group provided reassurance”. Feelings of support by the group was particularly important during times of lockdown as students had a platform to share lockdown experiences which was summarized by one student: “in our group, I could share my experiences of COVID-19”.

The presence of caring staff was often reported, as one student noted: “I feel that the lecturer really cares about us, by talking about the difficulties of COVID-19 and being flexible about getting assignments in because we are stressed out”. Connecting and being present for students was also found to be a reoccurring theme, as several recounted: “weekly face-to-face Zooms are essential”.

Material Space

There was a strong response that spoke to feeling comfortable within the physical space of the course where connections were made, which in this case for students, was the technological platform. While some reported that they did not have the necessary skills to even understand the online platform, one key theme spoke to the types of communication tools that were more useful over others to ensure the success of their communication within groups. One student described, “we had IT [information technology] issues with clunkiness when we used the university system so we had to find something that worked”.

Because the university learning system was generally regarded as “clunky” many turned to Facebook as an alternative as one student stated, “we had difficulties with Blackboard email, so went and used Messenger instead”. Alternatively, Whatsapp was used by several groups for communication. The use of Zoom was mentioned often, especially as this providing face to face time, which strengthened relationships. “Zoom made it feel like we were in the same room together. This was especially bizarre as one of the four of us was in a different state and another in a different country! This was one of the best assignments I have ever done, I made new friends and it was exciting being able to discuss thoughts and opinions, gaining new insights and perspectives” stated one student.

Others spoke to the benefits of communicating on a platform that was situated in spaces other than that of the university site where open conversations could happen with no risk to students learning or outcomes. Student comments were summed up by one student who stated, “It gave us the space to discuss our thoughts and opinions freely. Such an opportunity is valuable.”

For some, there were challenges in learning how to use some of the technology used in an online learning course. It was reported for example, that, “we were required to understand technology and [lockdown] forced us to learn that”.

Pedagogical Space

The course pedagogical design proved valuable in supporting student engagement and outcomes which was achieved through the addition of educational instruction that aligned with online practices such as team tasks that were student-directed, but visibly equitable and supported by the lecturer. To meet this end, the importance of group-work moderation and equal sharing of workload was stated by several students such as one who reported that, “we were worried about [a student] in our group not pulling her weight or turning up to meetings, but the lecturer has said that there will be marking consequences for people who do this and we also have the peer assessment to report this”, and another who commented that “the lecturer mediating group issues helped”. Others reported they had a sense of having to “pull their weight” despite the difficulties of working online during the pandemic: “shared goals are important because it resolved any conflict that arose and besides, we were on the same page and I did not want to let my team down”. The benefits elicited through engagement in the approach using student-directed group work during lockdown for participants related to a “decrease in the sense of isolation - which turned out to be very relevant” for many.

Discussion and Conclusion

The current study focuses on findings from a wider study that examined the learning benefits and challenges for students enrolled in a Masters’ course found with a set of online tools and features. Specifically, this study examined the responses from students that related to their perceptions of belonging within the course. It was deemed pertinent at this time to highlight the findings that were reported by students in connection with belonging as New South Wales continues lockdown conditions that has resulted in the closure of the university.

The main finding of this study was a recognition by students of the importance of feeling that they belonged and additionally, the strong sense of connectedness by students towards each other and staff. The findings also spoke to the significance of developing relationships with staff and peers.

Our data suggests that it is important to help students develop a sense of belonging and to understand the benefits of a sense of community. We believe that the application of an online teaching and learning model (see Figure 1) has served to provide the necessary components that enable a sense of student belonging. How this has been enacted is described in Figure 2, through spaces of belonging.

FIGURE 2. Online learning to create spaces of belonging [adapted from Baroutsis and Mills (2018)].

Relational space, manifesting via students experience of working with others, was promoted through the model’s provision of processes such as experiential learning and tasks undertaken through teamwork. It is worth noting however, that while students reported that they enjoyed the team aspect, this was not the case for all students. On few occasions, when students reported to the lecturer that they would withdraw if they had to complete a group task, because for example, they experience heightened anxiety in groups, they were offered alternative individual assessment tasks. Overwhelmingly, students reported that at the beginning of the course they were very reluctant to engage in the group work, but at the end of the task, could see learning benefits and that they “enjoyed the group work”. The material space that connected students was shown in the use of technology and design of the learning platform. Students needed to assist each other to complete tasks and at times did not have the skills and had to teach each other.

Finally, the impact of pedagogical space on student perception of belonging was demonstrated in student comments relating to where the model supported student-directed learning. This student-directed learning was assisted by a staff presence that served to provide students with help when needed.

How students engaged with each other and the relationship of teacher presence were all issues highlighted by Ahn and Davis (2020a) and Garrison (2016). Additionally, our data indicating the importance for students to develop a sense of belonging and to understand the benefits of a sense of community, also supports the findings from Mulrooney and Kelly (2020) who reported that reduction in students’ sense of belonging since lockdown, when the campus closed and teaching and learning was forced to move online “is unsurprising; seismic changes to the structure of the day, physical environment in which individuals worked and ability to socialize occurred at very short notice within an environment of widespread fear” (p. 7).

From a practical perspective we also agree with Mulrooney and Kelly (2020) who suggestion that successful belonging can be shaped by developing: a mix of asynchronous and synchronous learning so that social presence is provided and individual work is embedded; enhancing lecturer presence by using audio and video is given; allowing students who find online interaction more difficult to participate (e.g., using chat functions rather than speaking); ensuring that clear guidelines are provided to students, so that they understand how to participate, and why it is relevant and; evaluating all components of online teaching to understand which features are more successful than others. Where our results reported that students found the most helpful approaches to be those that assisted with minimizing isolation can also be explained by the concept of interactivity. Interactivity is a contextual factor that is formed between students/lecturer/content if communication exists at a sufficient level (Anderson, 2003). If levels of communication between students, lecturers and content is insufficient, then learning and student satisfaction are compromised (Croxton, 2014).

Our results are also consistent with findings from Farrell and Brunton (2020) who highlight that belonging can be achieved through successful online student engagement influenced by the peer community, an engaging online teacher, and course design. Our study also contributes the understanding that outcomes for learning are positive if these design mechanisms are put in place. The key word here is “successful”. If students experiences are positive, they are more engaged in turn, and are more motivated to contribute to their learning and assessment tasks. We note that the participant demographic information indicated that 84% of the cohort was female.

While low proportions of male participants are a typical problem of many online studies (Beißert et al., 2019), the gender relationship in this study is consistent with ratios in teacher education in New South Wales where two-thirds of all teachers are women (NSW Government, 2021). Gender however, is not considered to impact on the results of the study as gender was not, particularly as this would have been a “normal” learning environment for these students. However, as Table 1 depicts, most of the respondents were females aged between 30 and 50, and so we might assume that this cohort would be in a relationship and more probable to have children at home with them. This factor would affect the likelihood that the participants would be needing peer support.

To conclude, recent lockdowns in Australia have once again placed immense pressure on the lives of both students and lecturers. However, it has also provided an opportunity to deliver continuity for those enrolled in higher education that allows an ongoing sense of connectedness and belonging to their learning. It is hoped that the findings of this study will assist the ongoing development of online teaching and learning so that students’ needs can best be met in any circumstances.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by HREC, University of Newcastle. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

T-AG and AP contributed to the conception and design of the study. AP organized the survey and both researchers performed the thematic analysis. AP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. T-AG wrote sections of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Abdollahi, A., and Noltemeyer, A. (2018). Academic Hardiness: Mediator between Sense of Belonging to School and Academic Achievement? J. Educ. Res. 111 (3), 345–351. doi:10.1080/00220671.2016.1261075

Ahn, M. Y., and Davis, H. H. (2020a). Four Domains of Students' Sense of Belonging to university. Stud. Higher Edu. 45 (3), 622–634. doi:10.1080/03075079.2018.1564902

Ahn, M. Y., and Davis, H. H. (2020b). Students' Sense of Belonging and Their Socio-Economic Status in Higher Education: a Quantitative Approach. Teach. Higher Edu., 1–14. doi:10.1080/13562517.2020.1778664

Anderson, T. (2003). Getting the Mix Right Again: An Updated and Theoretical Rationale for Interaction. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distance Learn. 4 (2), 1–14. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v4i2.149

Araújo, N., Carlin, D., Clarke, B., Morieson, L., Lukas, K., and Wilson, R. (2014). Belonging in the First Year: A Creative Discipline Cohort Case Study. Int. J. of the First Year in Higher Edu 5 (2), 21–31. doi:10.5204/intjfyhe.v5i2.240

Aritz, J., Walker, R., Cardon, P., and Li, Z. (2017). Discourse of Leadership: The Power of Questions in Organizational Decision Making. Int. J. Business Commun. 54 (2), 161–181. doi:10.1177/2329488416687054

Baroutsis, A., and Mills, M. (2018). “Exploring Spaces of Belonging through Analogies of 'Family': Perspectives and Experiences of Disengaged Young People at an Alternative School,” in Interrogating Belonging for Young People in Schools. Editor C. Halse (Berlin: Springer), 225–246. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75217-4_11

Beißert, H., Köhler, M., Rempel, M., and Kruyen, P. (2020). Ein Vergleich traditioneller und computergestützter Methoden zur Erstellung einer deutschsprachigen Need for Cognition Kurzskala. Diagnostica 66 (1), 37–49. doi:10.1026/0012-1924/a000242

Benade, L. (2019). Flexible Learning Spaces: Inclusive by Design? The Professional Practice of Teaching. Editors M. Hill, and M. Thrupp (Boston, USA: Cengage Learning), 54, 53–68. doi:10.1007/s40841-019-00127-2

Bessant, K. C. (2018). “The Socio-Symbolic Construction and Social Representation of Community,” in The Relational Fabric of Community. Editor K. Bessant (Berlin: Springer), 155–183. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-56042-1_6

Braun, V., and Clarke, V. (2008). Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

Byers, T., Imms, W., and Hartnell-Young, E. (2018). Evaluating Teacher and Student Spatial Transition from a Traditional Classroom to an Innovative Learning Environment. Stud. Educ. Eval. 58, 156–166. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2018.07.004

Carvalho, L., and Yeoman, P. (2018). Framing Learning Entanglement in Innovative Learning Spaces: Connecting Theory, Design and Practice. Br. Educ. Res. J. 44 (6), 1120–1137. doi:10.1002/berj.3483

Chametzky, B. (2021). “Communication in Online Learning: Being Meaningful and Reducing Isolation,” in Fostering Effective Student Communication in Online Graduate Courses. Editors A. Scheg, and M. Shaw (Seattle, USA: IGI Global), 20–41. doi:10.4018/978-1-5225-2682-7.ch002

Chatti, M. A., Jarke, M., and Frosch-Wilke, D. (2007). The Future of E-Learning: a Shift to Knowledge Networking and Social Software. Int. J. Knowledge Learn. 3 (4-5), 404–420. doi:10.1504/ijkl.2007.016702

Cheung, C. M. K., Chiu, P.-Y., and Lee, M. K. O. (2011). Online Social Networks: Why Do Students Use Facebook? Comput. Hum. Behav. 27 (4), 1337–1343. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.07.028

Colón García, A. (2017). Building a Sense of Belonging through Pedagogical Partnership. Teach. Learn. Together Higher Edu. 1 (22), 1–5.

Croxton, R. (2014). The Role of Interactivity in Student Satisfaction and Persistence in Online Learning. MERLOT J. Online Learn. Teach. 10 (2), 314–325.

Daniels, H., Tse, H. M., Stables, A., and Cox, S. (2017). Design as a Social Practice: The Design of New Build Schools. Oxford Rev. Edu. 43 (6), 767–787. doi:10.1080/03054985.2017.1360176

Farrell, O., and Brunton, J. (2020). A Balancing Act: A Window into Online Student Engagement Experiences. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High Educ. 17 (1), 1–19. doi:10.1186/s41239-020-00199-x

Felicia, P. (2011). Handbook of Research on Improving Learning and Motivation through Educational Games: Multidisciplinary Approaches. Hershey, USA: IGI Global.

Garrison, D. R. (2016). E-learning in the 21st century: A Community of Inquiry Framework for Research and Practice. Milton Park: Taylor & Francis.

Garrison, D. R. (2011). E-learning in the 21st century: A Framework for Research and Practice. Milton Park: Routledge.

Gillett-Swan, J. (2017). The Challenges of Online Learning: Supporting and Engaging the Isolated Learner. Jld 10 (1), 20–30. doi:10.5204/jld.v9i3.293

Goodyear, P., Ellis, R. A., and Marmot, A. (2018). “Learning Spaces Research: Framing Actionable Knowledge,” in Spaces of Teaching and Learning: Integrating Perspectives on Research and Practice. Editors R. A. Ellis, and P. Goodyear (Basingstoke, UK: Springer Nature), 221–238. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-7155-3_12

Green, B., and Letts, W. (2007). “Space, Equity, and Rural Education: A ‘Trialectical’ Account,” in Spatial Theories of Education. Editors K. N. Gulson, and C. Symes (New York, NY: Routledge), 67–86.

Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., and Namey, E. E. (2012). Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Han, C.-w., Farruggia, S. P., and Moss, T. P. (2017). Effects of Academic Mindsets on College Students' Achievement and Retention. J. Coll. Student Dev. 58 (8), 1119–1134. doi:10.1353/csd.2017.0089

Hauge, Å. L. (2007). Identity and Place: a Critical Comparison of Three Identity Theories. Architectural Sci. Rev. 50 (1), 44–51. doi:10.3763/asre.2007.5007

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., and Bond, A. (2020). The Difference between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Educause Rev. 27 (1), 1–9.

Holbrook, A., Krosnick, J., and Pfent, A. (2007). “The Causes and Consequences of Response Rates in Surveys by the News media and Government Contractor Survey Research Firms,” in Advances in Telephone Survey Methodology. Editors J. M. Lepkowski, N. C. Tucker, J. M. Brick, E. D. De Leeuw, L. Japec, P. J. Lavrakaset al. (Hoboken, USA: Wiley), 499–678.

Hooks, B. (2008). Language: Teaching New Worlds, New Words. Rev. Estud. Fem. 16 (3), 857–864. doi:10.1590/S0104-026X2008000300007

Hu, H. (2015). Building Virtual Teams: Experiential Learning Using Emerging Technologies. E-Learning and Digital Media 12 (1), 17–33. doi:10.1177/2042753014558373

Iannone, P., and Simpson, A. (2017). University Students' Perceptions of Summative Assessment: The Role of Context. J. Further Higher Edu. 41 (6), 785–801. doi:10.1080/0309877x.2016.1177172

Kahu, E. R., and Nelson, K. (2018). Student Engagement in the Educational Interface: Understanding the Mechanisms of Student success. Higher Edu. Res. Dev. 37 (1), 58–71. doi:10.1080/07294360.2017.1344197

Knekta, E., Chatzikyriakidou, K., and McCartney, M. (2020). Evaluation of a Questionnaire Measuring University Students' Sense of Belonging to and Involvement in a Biology Department. CBE Life Sci. Educ. 19 (3), ar27–14. doi:10.1187/cbe.19-09-0166

Leal-Rodriguez, A. L., and Albort-Morant, G. (2019). Promoting Innovative Experiential Learning Practices to Improve Academic Performance: Empirical Evidence from a Spanish Business School. J. of Innovation & Knowledge 4 (2), 97–103. doi:10.1016/j.jik.2017.12.001

Leigh, K. (2019). “Chapter 5 Social Control and the Politics of Public Spaces,” in Political Authority, Social Control and Public Policy. Editors C. E. Rabe-Hemp, and N. S. Lind (Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited), 31, 95–108. doi:10.1108/S2053-769720190000031006

Lewis, K. L., Stout, J. G., Finkelstein, N. D., Pollock, S. J., Miyake, A., Cohen, G. L., et al. (2017). Fitting in to Move Forward: Belonging, Gender, and Persistence in the Physical Sciences, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (pSTEM). Psychol. Women Q. 41 (4), 420–436. doi:10.1177/0361684317720186

Means, B., Bakia, M., and Murphy, R. (2014). Learning Online: What Research Tells Us about whether, when and How. Milton Park: Routledge.

Moriña, A. (2019). The Keys to Learning for university Students with Disabilities: Motivation, Emotion and Faculty-Student Relationships. PLoS One 14 (5), e0215249–15. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0215249

Mulrooney, H. M., and Kelly, A. F. (2020). COVID-19 and the Move to Online Teaching: Impact on Perceptions of Belonging in Staff and Students in a UK Widening Participation university. Jalt 3 (2), 1–14. doi:10.37074/jalt.2020.3.2.15

NSW Government (2021). 2012-2020 Gender Analysis of School Teachers. Available at: https://data.cese.nsw.gov.au/data/dataset/gender-ratio-of-nsw-government-school-teachers/resource/84d23f64-dff6-4a24-8f13-1817fa00e507.

O'Duinn, J. (2018). Distributed Teams: The Art and Practice of Working Together while Physically Apart. San Francisco: Release Mechanix, LLC.

Page, A., Anderson, J., and Charteris, J. (2021). Innovative Learning Environments and Spaces of Belonging for Special Education Teachers. Int. J. Inclusive Edu. 4 (1), 1–16. doi:10.1080/13603116.2021.1968518

Peacock, S., Cowan, J., Irvine, L., and Williams, J. (2020). An Exploration into the Importance of a Sense of Belonging for Online Learners. Irrodl 21 (2), 18–35. doi:10.19173/irrodl.v20i5.4539

Peacock, S., and Cowan, J. (2019). Promoting Sense of Belonging in Online Learning Communities of Inquiry in Accredited Courses. Online Learn. 23 (2), 67–81. doi:10.24059/olj.v23i2.1488

Prosser, M., and Trigwell, K. (2000). Understanding Learning and Teaching. The Experience in Higher Education. Buckingham: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University.

QSR International (2020). NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software. Doncaster: QSR International Pty Ltd.

Quatrics (2019). Qualtrics XTM Platform. Available at: https://www.qualtrics.com.

Samura, M. (2018). Understanding Campus Spaces to Improve Student Belonging. About Campus 23 (2), 19–23. doi:10.1177/1086482218785887

Stephenson, J. (2018). Teaching & Learning Online: New Pedagogies for New Technologies. Milton Park: Routledge.

te Riele, K. (2018). “Reflecting on Belonging, Space, and Marginalised Young People,” in Interrogating Belonging for Young People in Schools. Editor C. Halse (Berlin: Springer), 247–259. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75217-4_12

Thomas, L. K., and Herbert, J. (2014). 'Sense of Belonging' Enhances the Online Learning Experience. The Conversation, 1–3. Available at: https://theconversation.com/sense-of-belonging-enhances-the-online-learning-experience-30503

van Gijn-Grosvenor, E. L., and Huisman, P. (2020). A Sense of Belonging Among Australian university Students. Higher Edu. Res. Dev. 39 (2), 376–389. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1666256

Yoon, S. J., and Gruba, P. (2017). “Constructive Alignment of Materials in Tertiary Programs,” in 34th International Conference on Innovation, Practice and Research in the Use of Educational Technologies in Tertiary Education. Editors H. Partridge, K. Davis, and J. Thomas (South Australia: ASCILITE), 441–449.

Keywords: belonging, higher education, online, community, isolation

Citation: Garrad T-A and Page A (2022) From Face-To-Face to the Online Space: The Continued Relevance of Connecting Students With Each Other and Their Learning Post COVID-19. Front. Educ. 7:808104. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2022.808104

Received: 03 November 2021; Accepted: 04 January 2022;

Published: 24 January 2022.

Edited by:

Shirley Dawson, Weber State University, United StatesReviewed by:

Nicos Souleles, Cyprus University of Technology, CyprusVicki S. Napper, Weber State University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Garrad and Page. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Angela Page, apage1@newcastle.edu.au

Traci-Ann Garrad

Traci-Ann Garrad Angela Page

Angela Page