Expansive Learning for Teacher Educators- The Story of the Norwegian National Research School in Teacher Education (NAFOL)

- Department of Teacher Education, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Trondheim, Norway

Internationally there is an increased focus on developing a research-based teacher education, and Norway is no exception. Teacher educators play a key role in teacher education, and research has become central to their work. Teacher educators are expected to be consumers and producers of research. Today teacher educators are projected to be teaching and research competent (Smith and Flores, 2019). However, many teacher educators become teacher educators with a background as successful teachers, and not all are research competent. Subsequently, they are required to engage in expansive learning to acquire research competence. They are expected to develop a second order expertise in addition to teaching which is for many their first order expertise (Murray and Male, 2005). This paper describes a national initiative in Norway intended to develop a research-based teacher education and strengthen teacher educators’ research competence. The Norwegian National Research School in Teacher Education (NAFOL) was established as a network comprising all, but one, teacher education institutions in Norway in 2010. NAFOL is funded by the Norwegian Research Council. In the paper the contextual background to NAFOL, its structure and content are described, followed by reporting on several evaluations of the research school. Conclusions from the evaluations document that the aims of NAFOL are achieved, and the research school has provided a supporting environment for teacher educators’ expansive learning related to qualification (Ph.D.), socialization into the academy and subjectification through close individual support (Biesta, 2009). The last part of the paper discusses factors that contribute to success and the challenges NAFOL faced. The main challenge has been handling the increasing number of applicants to the research school, and in the future Norway needs to look for new, inclusive models for teacher educators’ expansive learning. Other countries which aim to develop a sustainable research-based teacher education, should look to Norway and learn from the initiatives practiced in NAFOL about how to support teacher educators’ expansive learning.

Introduction

In the last decade there is an international political trend which calls for strengthening the research component in teacher education (Menter, 2015; Aspfors and Eklund, 2017). In 2005 OECD claimed that teachers’ profile, “clear and concise statements of what teachers are expected to know and be able to do” (OECD, 2005, p. 9), should be evidence based, and 2 years later the European Commission (2007) argued that “… practitioners and policy-makers should also be direct producers of knowledge, in collaboration with researchers. However, the tradition of such cooperation is not strong” (p. 6). Subsequently, in 2013, the European Commission repeatedly called for more research in teacher education claiming that “Both practice-based and theory-focused research can contribute to a deeper understanding of education and of educating teachers” (pp. 12–13).

There is, however, still an unclear understanding of what research-based teacher education means. Concepts such as evidence based, research-based, research informed, inquiry oriented, all express necessity of research in teacher education (Munthe and Rogne, 2015), and they are implemented in various ways in different national contexts. Nieme (2016) points out that in the Finnish context.

“…the concepts are used complementarily. Research-based means that teacher education is grounded in continuous research-based inquiry in academic disciplines, including educational sciences, and this provides a basis for the improvement of the curriculum in teacher education. Teacher educators in university departments and teacher-training schools are seen as teachers and researchers” (Nieme, 2016, p. 24).

Nieme clearly points at the dual responsibility of teacher educators, being teachers and researchers. Finnish teacher education has a long tradition of being research focused, and the position taken in this paper aligns with the four foci Krokfors et al. (2011) claim to be essential for a research-based teacher education:

(1) The study program is structured according to a systematic analysis of education.

(2) All teaching is based on research.

(3) Activities are organized in such a way that candidates can practice argumentation, decision-making and justification when inquiring about and solving pedagogical problems.

(4) The candidates learn formal research skills during their studies.

To be able to practice the four Finnish foci for teacher education, teacher educators are required to be research competent. To teach formal research skills, teacher educators need to know about and be active researchers themselves.

Norwegian teacher education has recently become quite similar to Finnish teacher education, yet with the lack of a long tradition for a strong academic teacher education. The Norwegian policy makers are clear in their demands for a research-based teacher education:

As with any other higher education, teacher education shall be research-based. The content of teacher education shall be based on up-dated knowledge. Research-based teaching also means that the education is characterized by scientific methods and oriented toward new ways of thinking and developing the practice field (Norwegian Ministry of Education, 2014: 44) (author’s translation).

The implementation of this policy led to the decision that from 2017 all teacher education beyond pre-school teacher education, is at a graduate level and the teacher education students are required to conduct research for their master dissertations. Additionally, it is expected that all teacher educators are sufficiently research literate to supervise the students’ master projects.

However, unlike Finland, per today all Norwegian teacher educators are not research competent, many of them hold a master’s degree and have experience from and expertise in school teaching. This situation is now changing, mainly because the institutions will only get accreditation for offering master programs if a certain percentage of the staff hold a doctorate, and secondly, promotion and funding are closely linked to the individual teacher educator’s publication list. The dual role of teacher educators as teachers and researchers (Cochran-Smith and Villegas, 2016; Smith and Flores, 2019) forced Norwegian teacher educators to engage in expansive learning, mainly in learning how to become research competent and to actively engage in research.

The demand of teacher educators to be active researchers is not unique for Norway or Finland. Cochran-Smith and Villegas (2016) who conducted an expansive review of US teacher education research, found that teacher educators conducted systematic research to develop new practices and insights into their own teaching at a local level, and they disseminated their findings beyond the local context by conceptualizing their new understandings. Such a practice-oriented approach to teacher educators’ research is likely to improve teacher education and the institutional level and beyond. The authors point out, however, that most US teacher educators working in universities would hold a doctorate.

This was not the situation in Norway and to upgrade teacher educators’ competence, planning in a long-term perspective, close cooperation between policy makers, teacher education institutions and leading national teacher educators led to the establishment of NAFOL, the Norwegian National Research School in Teacher Education in 2010. This is the story of how teacher educators from all over Norway were offered the opportunity, and grasped it, to engage in expansive learning and develop a new form for expertise, research, in addition to their primary expertise, teaching.

Establishing Nafol

To better understand why NAFOL was established, it might be useful to briefly describe the Norwegian context. Norway has experienced various reforms in teacher education in the last decade, and more information about this can be found in the paper by Munthe and Rogne (2016). Shortly, Norway has had two traditions to teacher education, the seminar tradition which is close to the logics of practice, and the discipline tradition with a focus on research within the disciplines (Afdal, 2012). The seminar tradition was evident in elementary school teacher education mainly taking place in teacher education colleges, whereas the disciplinary tradition characterized secondary school teacher education offered by the universities. This distinction is now disappearing for two reasons. As already mentioned, all teacher education is, from 2017, at a graduate level, and second, recently a merging process of universities and colleges has taken place in Norway. Most institutions offer today elementary as well as secondary school education. The recent strong academization of teacher education puts pressure on teacher educators to supervise candidates’ research projects and to publish their own research. Today teacher educators are expected to be research competent.

Another factor playing a central role in the establishment of NAFOL was the rather harsh criticism Norwegian educational research was subject to in a report by the Norwegian Research Council (2004). The research was criticized for being too theoretical and discipline focused, and of little use to the practical aspects of teacher education and teaching. The report recommended Norwegian teacher education institutions to focus on five areas for improvement: (1) research leadership and organization, (2) internationalization, (3) thematic efforts and prioritization, (4) recruitment, and (5) national coordination and cooperation (Østern and Smith, 2013).

As a follow up to the criticism, the Government announced in a White Paper (2009) that research schools in teacher education would be established to strengthen research in the effort to develop a research-based teacher education. The Norwegian Research Council was assigned to send out a call for research schools in 2009 (Østern and Smith, 2013). A remarkable factor in the establishment of NAFOL was that to avoid institutional competition in applying for funding, which might lead to smaller regional research schools, 22 Norwegian teacher education institutions (the following year two more were accepted into the network), agreed to jointly apply for funding for a true national research school in teacher education, which would be built on coordination and cooperation. A committee was appointed to write the application, and there was agreement of the structure and the leadership of the planned research school from the beginning. Full funding for 6 years was granted by the Research Council at the end of 2009, and the first cohort of doctoral candidates was accepted in January 2010.

Aim and Rationale

In the network application submitted to the Research Council of Norway in 2009 the aim of a national research school in teacher education was expressed as follows:

NAFOL will work to strengthen the quality of teacher education for all school levels through a structured, robust, and long-term investment in an organized doctoral education within a national network of cooperating higher education institutions (Norwegian University of Science and Technology [NTNU], 2009, p. 3).

The expression all school levels includes pre-school teacher education, and it has been an important goal in NAFOL to develop a research-based early childhood education, and to upgrade the research competence of pre-school teacher educators.

Another expressed perspective was that teacher education needs to develop its own knowledge base which emphasizes research-based knowledge and presents the uniqueness of practice and educational sciences in a broader perspective. The idea behind NAFOL was that developing such a knowledge base would take time, and it had to be done by the profession itself, by teacher educators who were active researchers. The national doctoral school would offer practicing teacher educators the opportunity to engage in doctoral studies with additional support and follow up (Norwegian University of Science and Technology [NTNU], 2009). Thus, NAFOL would create a framework for teacher educators’ expansive learning.

Expansive Learning

The ‘father’ of the concept ‘expansive learning’ claims that any learning theory should seek to answer four questions (Engeström (2001, p. 133):

(1) Who are the subjects of learning, how are they defined and located?

(2) Why do they learn, what makes them make the effort?

(3) What do they learn, what are the contents and outcomes of learning?

(4) How do they learn, what are the key actions or processes of learning?

In NAFOL the subjects of learning are practicing teacher educators who are located in teacher education institutions all over Norway, and their learning is, therefore, not confined to one institution, but takes place within a greater society (Engeström, 2015) of higher education institutions, schools and pre-schools. They learn because they want to expand their knowledge within a specific topic (research theme) and acquire new skills (research skills). The effort they make is huge, taking on a new role and engaging in activities previously unfamiliar to them. The outcomes of learning are likely to be new personal professional knowledge and contributing to a variety of knowledge fields, and, not least, obtaining a Ph.D. degree. NAFOL creates opportunities for individual learning (personal feedback) and learning in groups (small and larger groups), and the learning crosses boundaries as their doctoral projects are within different disciplines, apply different methods, and take place in different contexts. Thus, the learning opportunities offered by NAFOL reflect the metaphor of expansive learning which Sannino et al. (2016) argue “depicts the multidirectional movement of learners constructing and implementing a new, wider, and more complex object for their activity” (p. 603).

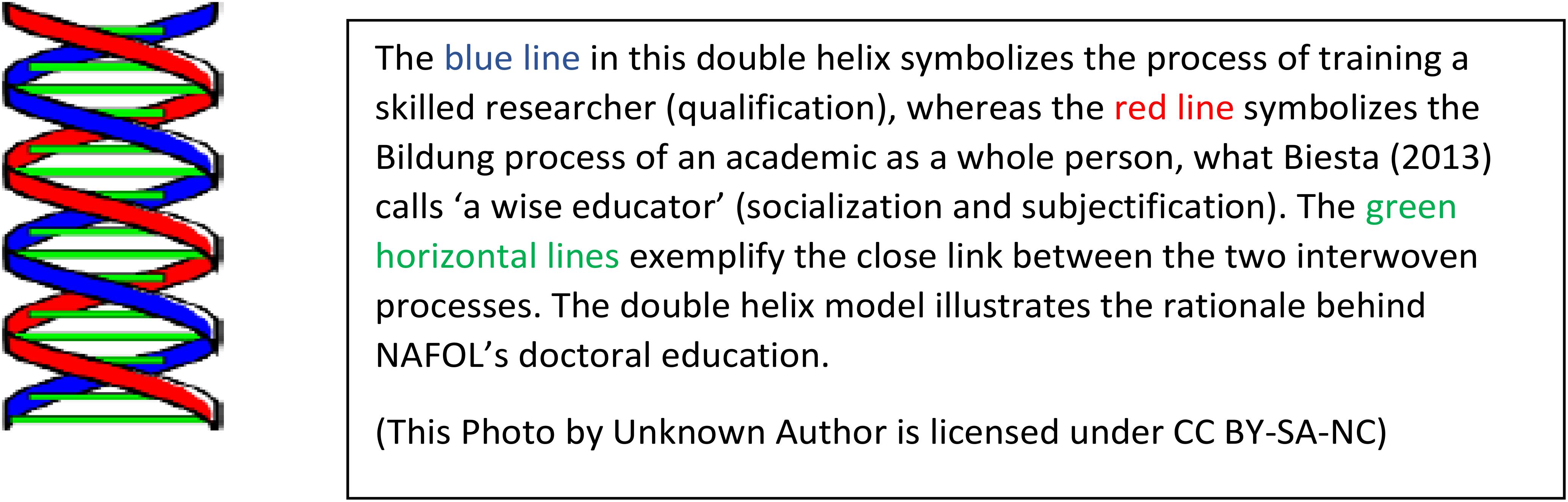

The rationale behind the research education in NAFOL is that we have taken an educative (Bildung) perspective in addition to having a strong training perspective in the process of educating new researchers for the academic community. The expansive learning of the NAFOL doctoral candidates is characterized by the fact that they go through a role change process, from being an acknowledged teacher to becoming an acknowledged researcher, however, without reducing their competence in teaching. It is not merely a question of being trained as a skilled researcher, it includes developing social and ethical standpoints and values related to taking on a professional identity as academics, being able to cooperate with colleagues and support each other. It is a question of developing resilience when things get tough, cope with setbacks, lack of progress and rejections of their academic work. Moreover, NAFOL stresses the importance of being open to presenting work in progress and to receive and provide constructive feedback within peer groups and expert groups. The bildung aspect of NAFOL is strong, as our rational is that the research school should educate a whole person, a scholar, holding social values, a person who is informed about aspects of the world beyond their own context and research projects. Thus, the theoretical foundations of NAFOL are rooted in a strong social-cultural perspective, and the various cohorts become communities of learning, based on trust and support (Wenger et al., 2002). During the 4-year NAFOL period the doctoral candidates have seminars hosted by teacher education institutions all over Norway and abroad. Each seminar includes social, cultural and often outdoor events in addition to an intense academic program.

The educational view on which NAFOL is based can be described by using Biesta’s work on the purposes of education; qualification, socialization, and subjectification (Biesta, 2009). NAFOL works toward the qualification for the degree of Ph.D., which is a major goal for the research school. In addition, the aim of NAFOL is to socialize the doctoral candidates into the academic community in a wide perspective, and finally, to focus on the development of the individual person within and beyond the relevant research field and community. A major goal is that every one of the candidates shall find her/his own professional identity as a researching teacher educator and act upon that. Thus, there is a strong emphasis on subjectification in the rational according to which NAFOL works. The learning is expansive, going beyond the respective research projects of the individual candidate. Biesta (2013) uses the term ‘becoming educationally wise’ which requires more than knowledge and skills, it also requires insights and independent positioning. He discusses “three reference points for thinking about the future of teacher education: a focus on the formation and transformation of the person toward educational wisdom; a focus on learning through the practicing of educational judgments; and a focus on the study of the educational virtuosity of others” (Biesta, 2013, p. 19). NAFOL has built a doctoral education for teacher educators founded on this view and has developed and continues to develop the program of the research school accordingly.

Network and Organization

Norwegian Research School in Teacher Education was established as a consortium of 24 teacher education institutions (universities and colleges) in 2010 with financial support by the Norwegian Research Council. Today the network consists of 17 institutions. It does not mean, however, that any institutions have withdrawn from NAFOL, but the reduced network is a result of a merging process in Norwegian higher education institutions. NAFOL has an external steering board which meets twice per year, and an advisory board in which all network institutions are represented. They meet once per year. The Head of NAFOL is a full professor employed by the university that administers the research school, and this institution also provides the administrative support. The research school consists of all Norwegian teacher education institutions besides one, and it is this network that ‘owns’ NAFOL.

The NAFOL program is 4 years, and the original project period was 6 years (till 2016). The aim was to educate 80 doctoral candidates in four yearly cohorts of 20 candidates. However, the project period has been continuously expanded upon the request of the policy makers, and additional funding has been provided. Currently NAFOL is planned to continue out 2021, and in addition to the 181 graduates, there are currently 86 candidates in the program in three cohorts. The last cohort accepted to NAFOL is cohort 10. Each cohort has a designated full professor as the coordinator and who is in close contact with the candidates during and in between the seminars.

The Candidates

Before providing more information about who the NAFOL candidates are, it is necessary to inform about the context of Norwegian doctoral education in general. The doctoral education in Norway is for a Ph.D. degree, and other degrees, such as Doctor in Education, Ed.D., are not accepted. All doctoral candidates in Norway are employed by a higher education institution, and they seek a position when applying to a Ph.D. program. This means that they are paid a reasonable salary on which they can live, and they enjoy the full rights of academic employees during the project period which is 3 full years or, as most doctoral candidates within education have, a 4-year period of 75% devoted to research and 25% to teaching in teacher education. It is rather difficult to get a Ph.D. position in Norway since the institutions publish a call internationally and in Norway for all openings, and the competition is keen. It is acknowledged that doctoral candidates in Norway enjoy better conditions for doing their Ph.D. than in many other countries.

All NAFOL doctoral candidates are practicing teacher educators or, recently, also practicing teachers from school involved with pre- and inservice teacher education. They work in all kinds of teacher education, from pre-school teacher education to upper secondary school, including leadership education, and within a variety of disciplines; sciences, humanities, social sciences, physical education, art education, domestic science, out door education, etc. NAFOL is proud that 25% of the doctoral candidate/graduates are related to pre-school teacher education. The candidates have practical experience and are in their thirties or beyond, often with family and children. The candidates are enrolled in a doctoral program in their respective institutions, and NAFOL offers additional support for 4 years. It is the respective institution that awards the Ph.D. degree, and NAFOL awards a certificate for participating in the research school. Thus, NAFOL offers an expansive learning process to the doctoral candidates. During the 10 years NAFOL has existed, it has become increasingly competitive to be accepted into the research school as the expansive learning NAFOL offers has become a sought-after support in taking a Ph.D.

The Program

In planning NAFOL there were clear aims for each of the 4 years; in the 1st year the focus is on becoming a member of a researcher community, next to becoming an academic writer in the second, moving into developing research skills to examine practice-theory dimensions in teacher education, leading up to the final year where publication and dissemination of research are emphasized. Throughout the 4 years written and oral communication, research skills, and the practice-theory linkage are emphasized alongside the urge to develop a critical and analytic competence.

The Norwegian doctoral education requires a minimum of 30 European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) in addition to the research dissertation. Each institution with doctoral programs offers doctoral courses, where research methodology and scientific theory are compulsory courses in most institutions, in addition to more specific courses related to the discipline or the research field. The NAFOL doctoral candidates engage in expansive learning beyond the common doctoral education as NAFOL offers four additional courses tailor-made for teacher education research, (1) professional theory of teacher education, (2) academic writing, (3) dissemination of research, and (4) teacher education research methodology. These courses are integrated into the 16 seminars the doctoral candidates have during the 4-year NAFOL period. To explain how the courses are integrated, it is necessary to provide more information about the structure of the program and the seminars.

Seminars

Each cohort of approximately 20–25 candidates are accepted into the program in January every year. In the following 4 years NAFOL organizes four 2–3 days seminars for each cohort hosted by the network institutions, all together 16 seminars for each cohort. Two of these seminars will be abroad, in cooperation with a university in one of the Nordic countries and in a European country. The seminars abroad last for 3–4 days. Norway is a long country with big distances, and NAFOL covers travel (usually flights) and hotel accommodation expenses for all candidates for all 16 seminars. The content of the seminars is planned in accordance with the yearly aims presented above, and care is taken that there is a clear progression in the program. The progression follows the various stages in working on a doctoral dissertation, with input from national and international guest speakers, and assignments subject to peer and expert feedback in smaller groups. Each assignment is closely related to the dissertation, e.g., forming research questions, writing a literature review, establishing a theoretical framework, presenting the methodology, findings, and writing the discussion. As most NAFOL candidates choose to have an article-based dissertation, much time in the seminars is spent on writing for publication in peer-reviewed journals. Oral and written dissemination to a variety of stakeholders is an additional component of the seminars. Each seminar offers a module of two or more of the expansive doctoral courses in the NAFOL program.

The seminars usually start with a brief artistic performance, followed by an intense academic program. There is a cultural event in the evening and a joint dinner.

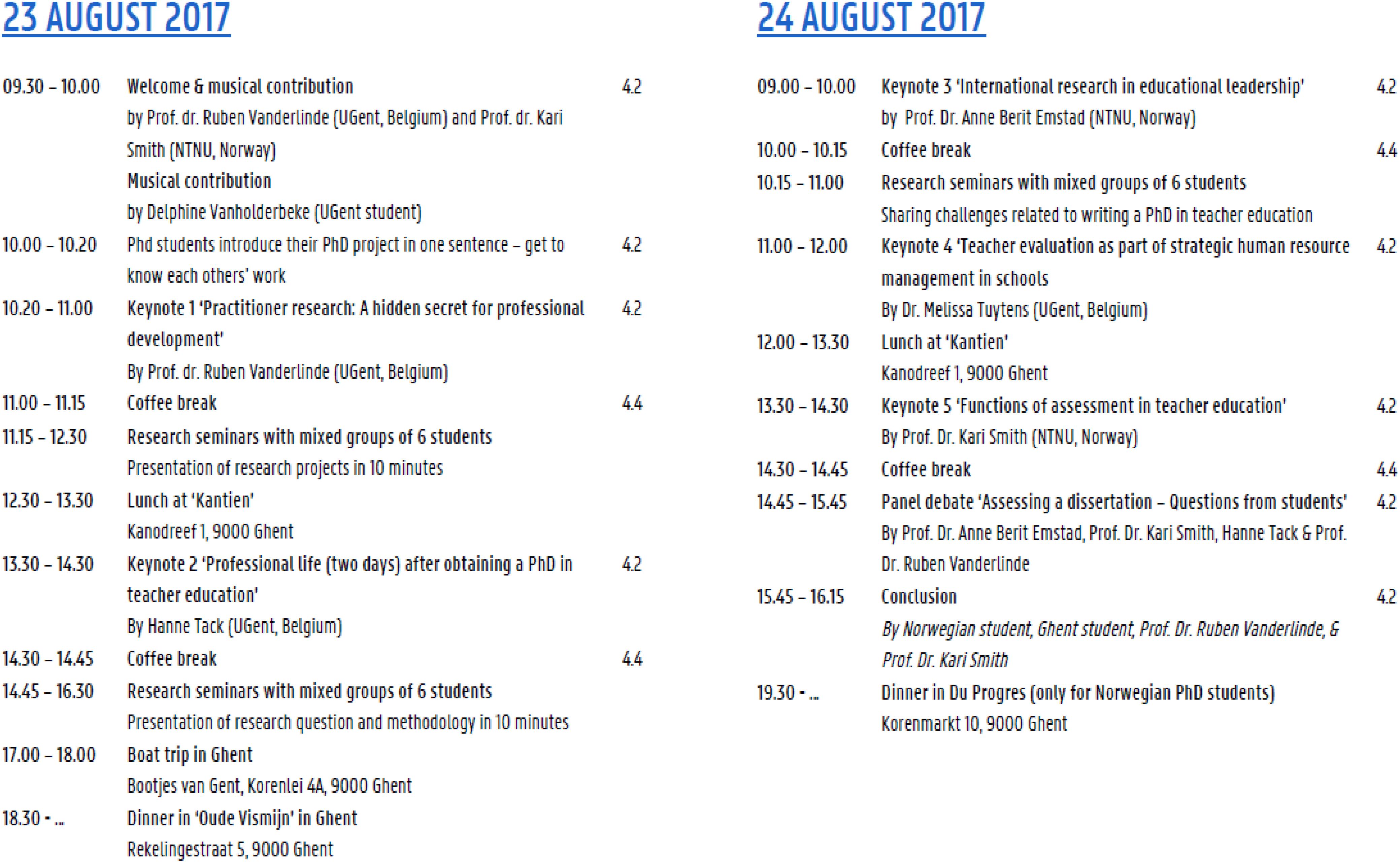

An example of an international NAFOL seminar in cooperation with Ghent University illustrates the above description. In addition to the 2 days with candidates from Ghent, the Norwegian candidates had a 3rd day with master classes and process-seminars which will be explained below (see Figure 2).

Figure 1. NAFOL’s rationale. The blue line in this double helix symbolizes the process of training a skilled researcher (qualification), whereas the red line symbolizes the Bildung process of an academic as a whole person, what Biesta (2013) calls ‘a wise educator’ (socialization and subjectification). The green horizontal lines exemplify the close link between the two interwoven processes. The double helix model illustrates the rationale behind NAFOL’s doctoral education. (This Photo by Unknown Author is licensed under CC BY-SA-NC).

Master Classes and Process Seminars

Academics are expected to present their research for feedback and criticism from the academic community, and NAFOL’s doctoral education aims to prepare the candidates for the tough reality in the academy. In addition to constructive feedback the candidates receive from peers and experienced researchers on short assignments in small groups, NAFOL also offers, to expand the candidates’ learning, expert feedback on longer texts, articles, in master classes and on the full dissertation in process-seminars.

When a NAFOL candidate has a complete draft of an article, he/she is given the possibility to engage in a constructive feedback dialog with an invited expert in the field who is not the candidate’s supervisor, in a master class. This takes place prior to submitting the article to a peer reviewed journal. The expert reads the article in advance and prepares a formative feedback session of 45 min with the candidate and peers from the cohort in the audience. The feedback is used when finalizing the article for submission to the journal. The doctoral candidates are given the possibility to have a masterclass for all three/four articles of the dissertation.

An article-based dissertation in Norway normally consists of three/four articles and an extended meta-text of up to 100 pages which conceptualizes the project by writing more extensively about the theoretical framework, discussing relevant research in depth, presenting the theory of the selected methodology and synthesizing the findings of the various articles. Subsequently, the Norwegian article-based dissertation should reflect scholarly knowledge at a high level and research competence documented in the published articles. The NAFOL candidates are offered the opportunity to present a full draft of the dissertation to an external reader for formative constructive feedback in a process-seminar before finalizing the dissertation for submission. The external reader will be an acknowledged professor, national or international, from the respective field of the doctoral project. The process-seminar is open to other NAFOL candidates and lasts for about 90 min. NAFOL covers all expenses for master classes and process-seminars. This is an important factor in the effort to expand the learning of the doctoral candidates beyond the doctoral program of their institution and the supervision team.

Summer Schools and Conferences

Within the cohort the doctoral candidates establish a strong community of learning as they meet four times per year. All the candidates in a cohort will be at more or less the same stage in the doctoral project, thus they support each other in facing similar challenges. However, the whole NAFOL community offers a wider community of learning, and therefore one of the seminars every year is a cross cohort seminar in the form of a summer school or an international conference.

The biannual summer school has become a rather big event as all NAFOL doctoral candidates, their supervisors, and NAFOL alumni are invited to participate. National and international researchers are invited for plenary presentations, debate sessions and feedback sessions in cross cohort groups. The candidates are invited to engage in professional dialogs with each other and with a variety of renowned researchers and scholars. As in the other seminars, social and cultural activities are included.

In the year when NAFOL does not organize a summer school, there is an international conference to which all NAFOL candidates, supervisors, alumni, and two doctoral candidates from each of the Nordic and European universities NAFOL has worked with. International and national high-profile researchers are invited for keynotes and workshops. All NAFOL candidates must present at this conference, either a poster, paper, roundtable or symposium with discussants. The candidates are given the role of introducing and thanking keynote speakers, chairing sessions and acting as chairs of panel discussions. These are roles they are expected to take on as academics, and at the NAFOL international conferences they are given the opportunity to practice in a low-stake setting. Moreover, the cohort in its fourth year is given the responsibility to organize and lead the social events and conference dinner. The conference becomes an important arena for the NAFOL candidates to expand their learning beyond the cognitive aspects, they are socialized into the academic world.

Keynote speakers and candidates who present papers at the conference are invited to submit their presentations for publication in the NAFOL book. The process of having a paper accepted is rigorous, first an abstract of 1,000 words goes through blind review, and those that are accepted, are invited to submit full papers which again are subject to blind reviews. At the end, only the best papers are accepted for publication in the book which is published by a well-known Norwegian publisher. The fourth book, Value and Validity in Teacher Education Research, is expected to be published early 2020. The book offers an additional opportunity for the NAFOL candidates to expand their learning.

Financial Support

The many activities described above are free of cost for all NAFOL candidates which makes it possible for equal participation once they are accepted into the program. The research school also offers financial support for active participation in international conferences and for study leaves at a university outside Norway. NAFOL supports the candidates in finding suitable places where they will have an onsite mentor and opportunities to discuss their work with other doctoral candidates and researchers. Norway is a small country, 51/2 million people, and we depend on international cooperation and networks. One of NAFOL’s aim is to strengthen the internationalization of Norwegian teacher education and teacher education research. Learning is expansive beyond Norway, a must in the era of globalization. NAFOL is funded by the Norwegian Research Council which receives earmarked funding from the Government.

Results/Evaluation

When a nation invests so heavily in developing a research-informed teacher education and strengthening teacher educators’ research competence, there is an implied claim that the national research schools must meet the expectations and fulfill the expressed goals. NAFOL has been evaluated in various ways during these 10 years, and in the following some of the results from these evaluations are presented.

Extended Funding

The most common periods for projects funded by the Norwegian Research Council are 3 years for research projects and 6 years for research schools. As mentioned above, when NAFOL received the first funding in 2010, it was for 6 years, and the aim was to educate 80 teacher educators for a Ph.D. degree in four cohorts, however, the actual number was 100. As NAFOL became known and respected among teacher educators and teacher education institutions, the number of applicants increased, and continuous additional funding was granted without any formal application to the Research Council by the NAFOL network institutions. NAFOL was required to write a yearly report on its activities, the progress of the doctoral candidates and the financial management, and year after year further funding was provided. As for now, the extended project period is 12 years, ending in 2021. By then 10 cohorts will graduate from the research school, three of which are currently in the process. Cohort 9 consists of two groups of 22 candidates each. The reason for having a cohort with two groups was that the number of applicants was so high that despite a considerable rejection rate, the Steering Board found it necessary to accept two groups to cohort 9 to meet the demands of the network institutions.

External Interim Evaluation 2013

It is common in Norway that a research school with rich external funding becomes subject to external evaluation by an international evaluation team. This was also the case with NAFOL, and in 2013 the external evaluation report was submitted. The material used by the external evaluation team were the application submitted by NAFOL to the Research Council, NAFOL’s self-evaluation, additional information about the activities, evaluations by 21 network institutions and interviews with NAFOL representatives, management and candidates (Norwegian Research Council, 2013).

The conclusions of the report reads:

NAFOL is well organized with a clear structure, which can be attributed to a well-functioning management consisting of a scientific leader, a consciously structured administration, a board and a council. Both Ph.D. students and supervisors from the partner institutions meet and build networks. Overall, the partner institutions are very satisfied with the cooperation. NAFOL maintains a high profile in terms of internationalization. The strategic importance of the research school is considered very important. There is a clearly set out plan for the school for the whole period until the end in 2016. All in all, NAFOL shows high goal achievement. However, three factors of uncertainty have been identified – collaboration with a kindred research school, NATED1, vulnerability related to the replacement of people in leading managing positions and concern for what will happen after 2016 (Norwegian Research Council, 2013, p. 11).

National Research School in Teacher Education situates the expansive learning of the candidates in new networks created across the country and across research topics and methods, thus, teacher educators’ learning crosses boundaries (Engeström and Sannino, 2010). The three vulnerable factors turned out to be less of a challenge than expected, as the related research school did not continue after 2015, leading people who retired were replaced by others who were engaged in NAFOL in different roles, and the project was extended, so the worries about post 2016 have now become the worries of post 2021.

Self-Evaluation 2015

Upon request from the Research Council in August 2015, NAFOL was told to conduct a wide self-evaluation to be submitted to the Research Council by the end of 2015. This was a central document in deciding whether to extend the NAFOL period and expand the funding beyond the original first 6 years. The Academic Head of NAFOL was responsible for the self-evaluation, however, she hired an external researcher to collect data from the network institutions and alumni to reduce the many biases related to self-evaluation. The research question that guided the self-evaluation was: How do network institutions, represented by deans, graduates, and of NAFOL’s founders, perceive the impact of NAFOL’s work in its first project period? (Vattoy and Smith, 2018).

Data were collected by questionnaires to deans of teacher education in the network institutions and NAFOL alumni. In addition, interviews took place with central people in NAFOL, and recordings from a Council and a Steering Board meeting. The extensive report was submitted to the Research Council in November 2015 (Smith, 2015), and a paper, Developing a Platform for a Research-Based Teacher Education (Vattoy and Smith, 2018) summarizing the report, was published in 2018 in the NAFOL book, Where are we? Where do we want to go? What do we want to do next? International and Norwegian Teacher Education Research (Smith, 2018). The main findings of the self-evaluation suggest that

NAFOL’s main contribution centers around three areas: establishing networks and cooperation, developing a teacher educator identity, and research linking theory and practice in teacher education, whereas the main criticism relates to attention to early childhood education (Vattoy and Smith, 2016, p. 35).

The findings suggest that NAFOL fulfills its aims to develop a knowledge base in teacher education and to strengthen the research competence of teacher educators. The candidates appreciate the support of relevant networks, and they develop an identity of teacher educators as researchers, they go beyond their comfort zone mediated by peers and experienced researchers (Engeström, 2001).

Even though 25% of the candidates work in pre-school teacher education, the program has not been planned with this specific group in mind. NAFOL candidates work with education of teachers at all school levels and with all school subjects, and the program addresses general aspects of writing a dissertation and developing academic competence in teacher education, and it does not tailor the program to specific thematic domains within teacher education. Hence, the criticism of lack of attention to early childhood education is justified, and similar criticism could also have come from, e.g., secondary school teacher educators, math teacher educators etc.

External Evaluation 2018 (Master Thesis)

In 2017 a master thesis examining the impact of NAFOL on its alumni was submitted to a Norwegian university (not the host university) by a graduate student with no relation to NAFOL whatsoever (Sunde, 2017). The thesis was summarized in an article which will be published in the forthcoming NAFOL book, Value and Validity in Teacher Education Research (Smith, 2020). This study was a qualitative study based on in depth interviews with 8 NAFOL alumni exploring the question How do NAFOL alumni experience the participation and their own learning and development in NAFOL? (Sunde, 2020). The main findings show that NAFOL provided:

(a) A close supporting network which the candidates’ respective institutional doctoral programs did not provide.

(b) Participation in a strong academic community.

(c) Knowledge about how to conduct research.

(d) Professional and social networks.

(e) Shared responsibility for providing mutual support in the peer group.

(f) Additional supervision and feedback throughout the doctoral project.

(g) Learning an academic language.

(h) Low threshold for communication (Sunde, 2017, 2020).

The above findings indicate that NAFOL provides a framework for teacher educators’ expansive learning in the process of taking on a dual role as teachers educators, that of teachers and of researchers (Smith and Flores, 2019). Sunde (2020) who has called his paper, Everybody should have a research school, concludes that the scientific community of learning in a research school is a good and important arena for professional development.

Numbers

The above evaluations document that NAFOL has been working according to the expressed goals in the application submitted to the Research Council in 2009. The socialization and subjectification processes the candidates experience in NAFOL are emphasized in the different evaluation activities. However, by the end of the day NAFOL has been, and will be, evaluated according to the measurable achievements, the Ph.D. qualification of the candidates. Does the expansive learning framework offered by NAFOL accumulate in an expansive qualification for Norwegian teacher educators? Hence, it is necessary to look at the figures representing the measurable contribution of NAFOL to developing a research-based teacher education and to strengthen the research competence of Norwegian teacher educators.

This section will briefly present figures related to candidates, completed dissertations, attrition, and publication and dissemination of research.

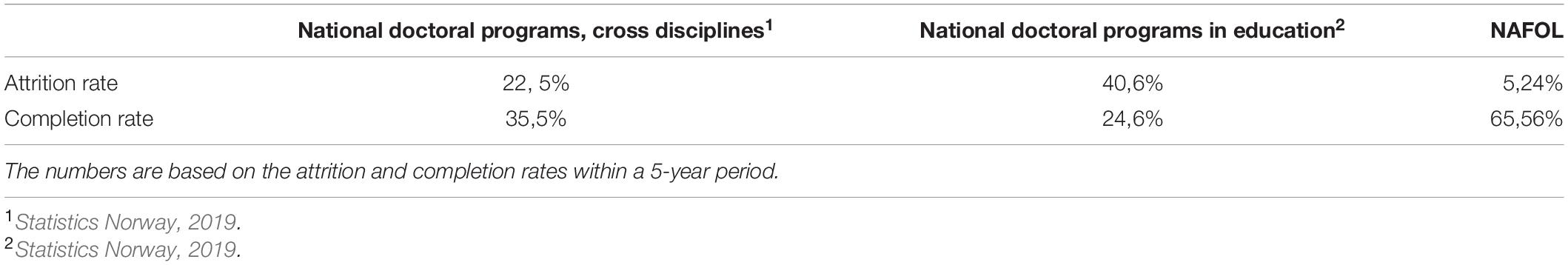

Since 2010, 267 candidates have been accepted to NAFOL. Out of these 12 have left the program, mainly due to severe health problems, and 2 have left their doctoral studies after the NAFOL period. That means that the attrition rate is 5.24%. The national attrition rate from doctoral programs is 22.5% cross disciplines, and 40.6% in education (Statistics Norway, 2019). Currently there are 86 candidates in the program, cohorts 8, 9 (two groups), and 10. The last intake (cohort 10) was January 2019, and these candidates will only have 3 years in NAFOL as the end of the project is the end of December 2021.

The completion rate of accepted doctoral dissertations in all disciplines in Norway after 5 years is 35.5%. For teacher education and educational dissertations, the completion rate is 24.6% within 5 years (Statistics Norway, 2019). The completion rate in NAFOL is 65.56%, and all dissertations are within the domain of teacher education.

In 2019 NAFOL candidates published 26 peer reviewed papers and presented 61 papers at scientific conferences. This number represents only 1 year, and on average we could multiply this by 8 years (assuming that not much publications took place in the two 1st years of the research school). The NAFOL candidates have contributed with 208 empirical peer reviewed papers to the Norwegian researched based knowledge in teacher education. 61 conference presentations per year adds to the dissemination of Norwegian teacher education research, amounting to 488 conference presentations. For such a small country as Norway and Norwegian teacher education the above numbers are significant. NAFOL has contributed to developing a stronger research-based teacher education.

An additional summative evaluation of NAFOL will be conducted by an external group of evaluators and administered by the Norwegian Research Council in 2021.

Discussion

In the following discussion the reasons for the success of NAFOL as documented in the various evaluations and reported numbers will be addressed before elaborating on the challenges NAFOL has experienced and some worries about the future of expansive learning of teacher educators.

The main task of NAFOL has been to support teacher educators in the process of becoming researchers in addition to their roles as teachers. This is a difficult process, developing a new form of expertise (Murray and Male, 2005; Czerniawski et al., 2017), especially under the explicit pressure from policy makers to make teacher education more research-based. In addition, many teacher educators realize they are obliged to engage in research in order to continue working in teacher education. They are expected to supervise master thesis, and publications are central to their career in the academy (Smith and Flores, 2019). Cochran-Smith (2005) claims that engaging in research is an integrated component of any teacher educator’s job responsibility, which aligns with Krokfors et al. (2011) definition of what constitutes a research-based teacher education presented in the introduction of this paper. NAFOL is a research school in teacher education, and the focus has always been on practice-oriented research relevant to the practice field. Teacher educators must find a balance between teaching and research, and a way to combine both (Vanassche and Kelchtermans, 2016). The NAFOL research profile as stated in the grant application has from the beginning been subject teaching methodology (didactics), teachers’ mandate in society, and the teaching profession and professional development. Teacher educators are given the possibility to expand their roles beyond being a teacher to also becoming a researcher within their respective professional interests in their doctoral projects. However, starting a doctoral education is found to be a difficult process, and Jones (2013) concludes in a large review study of doctoral education over 40 years that many doctoral students feel isolated and lonely. In NAFOL the students are, as previously mentioned, accepted into cohorts which become communities of learning and of practice.

Lave and Wenger (1991) define communities of practice as an arena within which participants are given the opportunity to develop special competence through social practices and experts. The cohort serves as a community of practice and learning over 4 years. The candidates are all in the same stage of their doctoral projects, they learn to trust their peers and the cohort coordinator, and the threshold level of communication is low. This leads to the fact that they are open to provide and receive constructive feedback, and to talk about the challenges they face. Friendships are created in addition to very strong professional networks across the country and beyond. The candidates experience they can engage in their expansive learning processes in a safe environment with peer and expert support (Vattoy and Smith, 2018). This might explain the low attrition rate from NAFOL, and the high completion rate compared to the national average.

The cohorts meet four times per year for 4 years outside their own institutions which provides time and space to develop close social relations. In the seminars they meet international and national experts who comment on their work. This creates motivation to attend the seminars and to prepare the assignments (Vattoy and Smith, 2018). Much work is done in small groups, and the candidates are expected to present texts for discussion. Moreover, the assignments are also obligatory for the integrated doctoral courses in NAFOL. There is a kind of social, as well as, structural pressure to produce. They are induced into a continuously evolving process in their doctoral work. It is difficult to be active in NAFOL without experiencing progress. The dissertation is over the 4 years broken into manageable tasks which toward the end take the form of full papers or a complete dissertation. Continuous formative and constructive feedback throughout the 4 years is the core of NAFOL and essential to completing the projects. The feeling of not having progress, of being stuck, is found to be a major reason for attrition from doctoral programs (Jones, 2013). The candidates are qualified as researchers with a Ph.D. degree, and at the same time they are socialized into the academy, creating strong professional networks within their own subjective professional engagement. NAFOL has become a community which aims to practice Biesta’s (2009) goals of education.

Another reason for NAFOL’s success can be ascribed to the strong financial support the candidates have available to expand their learning beyond a regular doctoral program. They are given the opportunities to attend conferences and to visit international institutions and create global networks. The candidates do not have to worry about the financial aspects of expanding their learning, which probably is unique in any doctoral education. The Norwegian policy makers have invested heavily in developing a strong research-based teacher education, and NAFOL has been the core of this investment (Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge, 2006–2007, 2008–2009).

The success of NAFOL has, however, also become its main challenge which is elaborated in the next section.

Challenges

When the research school was established, there was a concern that NAFOL would not have enough candidates, and the aim of having cohorts of 20 seemed to be visionary. Therefore, each network institution committed to provide a specific number of candidates in the 1st years. However, already after the 2nd year, when NAFOL became known, the number of applicants per year increased, and an increasing number of applicants were rejected. Keeping in mind that all applicants had already been admitted to a doctoral program based on a detailed project description in one of the network institutions, NAFOL was not in a position, or did not find it ethically correct, to reassess the quality of the project descriptions. Other criteria such as relevance to teacher education and NAFOL’s three research domains, and motivation for engaging in expansive learning beyond the institutional doctoral program, were applied. Still, many applicants were found suitable, and as a result two cohorts had 30 candidates and more. However, it became clear that in large cohorts there were a few candidates who were less active, and their participation and progress were not as expected. They were less socialized into the group, and the benefits of the NAFOL activities were not fully exploited. This affected their doctoral work and the completion of the dissertation. Hence, in 2018 the Steering Board decided to have two groups within the cohort (9), each group given a coordinator, to be able to accept more candidates, yet at the same time to maintain the advantages of working within a small community of learning.

NAFOL has become an integrated part of Norwegian teacher education institutions in their efforts to strengthen teacher education research. The institutions are under pressure to employ research competent people with a Ph.D.- degree, and a growing number of positions for doctoral candidates are offered. In the last years the number of applicants to NAFOL has increased, and the rejection rate has been beyond 60%. This means that in many institutions there are two groups of candidates enrolled in their educational doctoral programs, those who are accepted into NAFOL and those who are not. An example is taken from a large university which have nearly 70 doctoral candidates in teacher education, however, only 8 of them are currently accepted to NAFOL. As emphasized in this paper, NAFOL provides expansive learning and individually tailored support to its doctoral candidates which is found to increase the chances for completion. When some candidates in an institution’s doctoral education enjoy these benefits and others do not, an A and B team of candidates are created. As some of the NAFOL candidates say, “We are members of the national Olympic team.” This is a challenging situation for many network institutions.

NAFOL was established to develop a research-based teacher education by educating teacher educators to become researchers and academics in a time when Norway really needed a courageous and innovative national investment such as a well-structured, high quality and richly funded research school. The success of NAFOL has been described in this article. Today, however, the situation has changed, and the success has created a challenge that requires new bold innovative models for expanding teacher educators’ learning as researchers in the future. New models should be inclusive, and not exclusive, as NAFOL due to its huge success, has become. It is therefore timely that the current structure of NAFOL ends in 2021, and different initiatives are tried out and implemented.

Already in 2019 did the NAFOL management, in cooperation with the Steering and Advisory Board, start discussing possible future models which will keep the network intact on one hand, however, include all doctoral students and not only cater for an exclusive group on the other hand. This is still work in progress, in dialog with the Norwegian Research Council and the policy makers. The direction is that the institutional doctoral programs will take over the responsibility for creating strong networks and individual support, whereas the national research school will offer doctoral courses specifically relevant to teacher education research and be responsible for annual seminars/conferences with international speakers and spaces for presenting work in progress for formative feedback from peers and experts.

Conclusion

In this paper the unique initiative of creating a national research school in teacher education has been described. NAFOL was right when it was established in 2010 and has contributed to developing a rich research supported knowledge base in, of, and for teacher education (Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge, 2017). It has been a major factor in the quantum leap Norwegian teacher education research has had and is currently experiencing.

The success of NAFOL is due to the national needs, national investment, the structure, pedagogical and social activities, quality of academic and administrative staff, and not least the dedication of the candidates. The teacher educators chose to, and invested in, expansive learning which took place at several levels, first and foremost in acquiring research competence and a doctoral qualification. Second, they chose to expand their learning beyond a regular doctoral education and participate in NAFOL with its additional requirements and support. Thirdly, the learning expands across Norway, Scandinavia, and Europe.

NAFOL has become well known internationally and acknowledged in European policy documents:

In Norway, the Ministry of Education and Research has started a research program for teacher educators (PRAKUT), engaging them in practice based educational research in close cooperation with schools. This program is supported by a National Graduate School in Teacher Education (NAFOL), where teacher educators can join Ph.D. programs. While supporting the development of teacher educators’ research expertise, this initiative also contributes to the development of the knowledge base on teaching, teacher educators, and teachers (European Commission, 2013, pp. 24–25).

Success, however, is context and time dependent, and NAFOL was right when it was established in 2010 and till 2021. However, in the future new models for ensuring teacher educators’ expansive learning must be developed, as there is still a long way to go, also according to Norwegian Policy makers (Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge, 2017). The accumulated experiences from NAFOL presented in this paper can expand the learning of policy makers and teacher education institutions in other countries about how to develop national models for expanding teacher educators’ learning.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

KS was a professor of Education at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU). She was an experienced school teacher and teacher educator, and she was currently the Head of the Norwegian National Research School in Teacher Education (NAFOL). She was, until this year, the Chair of the International Forum for Teacher Educator Development (InFo-TED). Her main research interests are assessment and professional development at all levels of education. She has published widely and is often invited to present her work internationally.

Funding

NAFOL was funded by the Norwegian Research Council and owned by the NAFOL network of teacher education institutions. Information about NAFOL and the network can be found here: https://nafol.net/en/nafol/.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

- ^ NATED, National Graduate School in Educational Research.

References

Afdal, H. W. (2012). Knowledge in teacher education curricula – Examining differences between a research-based programme and a general professional programme. Nord. Stud. Educ. 32, 245–261.

Aspfors, J., and Eklund, G. (2017). Explicit and implicit perspectives on research-based teacher education: newly qualified teachers’ experiences in Finland. J. Educ. Teach. 43, 400–413.

Biesta, G. (2013). “Becoming educationally wise: towards a virtue-based conception of teaching and teacher education,” in Teacher Education Research between National Identity and Global Trends, eds A. L. Østern, K. Smith, T. Ryhaug, T. Krüger, and M. B. Postholm (Trondheim: Akademia Publishing), 29–52.

Biesta, G. J. J. (2009). Good education in an age of measurement: on the need to reconnect with the question of purpose in education. Educ. Assess. Eval. Accountabil. 21, 33–46. doi: 10.1007/s11092-008-9064-9

Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). Teacher educators as researchers: multiple perspectives. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.003

Cochran-Smith, M., and Villegas, A. M. (2016). “Research on teacher preparation: charting the landscape of a sprawling field,” in Handbook of Research on Teaching, 5th Edn, eds D. Gitomer and C. Bell (Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association), 439–547. doi: 10.3102/978-0-935302-48-6_7

Czerniawski, G., Guberman, A., and MacPhail, A. (2017). The professional developmental needs of higher education-based teacher educators: an international comparative needs analysis. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 40, 127–140. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2016.1246528

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. J. Educ. Work 14, 133–156. doi: 10.1080/13639080020028747

Engeström, Y. (2015). Learning by Expanding: An Activity-Theoretical Approach to Developmental Research, 2nd Edn. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Engeström, Y., and Sannino, A. (2010). Studies of expansive learning: foundations, findings and future challenges. Educ. Res. Rev. 5, 1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002

European Commission (2007). Improving the Quality of Teacher Education. Brussel: European Commission.

European Commission (2013). Supporting Teacher Educators for Better Learning Outcomes. Brussel: European Commission.

Jones, M. (2013). Issues in doctoral studies - Forty years of journal discussion: where have we been and where are we going? Int. J. Doct. Stud. 8, 83–104.

Krokfors, L., Kynäslahti, H., Stenberg, K., Toom, A., Maaranen, K., Jyrhämä, R., et al. (2011). Investigating Finnish teacher educators’ views on research-based teacher education. Teach. Educ. 22, 1–13. doi: 10.1080/10476210.2010.542559

Lave, J., and Wenger, E. (1991). Situated Learning : Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

Munthe, E., and Rogne, M. (2015). Research-based teacher education. Teach. Teach. Educ. 46, 17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2014.10.006

Munthe, E., and Rogne, M. (2016). “Norwegian teacher education: development, steering and current trends,” in Do universities Have a Role in the Education and Training of Teachers? An International Analysis of Policy and Practice, ed. B. Moon (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 35–55.

Murray, J., and Male, T. (2005). Becoming a teacher educator: evidence from the field. Teach. Teach. Educ. 21, 125–142. doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.006

Nieme, H. (2016). “Academic and practical: research-based teacher education in Finland,” in Do Universities Have a Role in the Education and Training of Teachers? An International Analysis of Policy and Practice, ed. B. Moon (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press), 19–35.

Norwegian Ministry of Education (2014). Lærerløftet: På lag for Kunnskapsskolen [Lifting the Teachers: On the Same Team for the Knowledge School]. Available at: https://www.regjeringen.no/globalassets/upload/kd/vedlegg/planer/kd_strategiskole_web.pdf

Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge (2006–2007). Government White Paper no. 16. …Og Ingen Stod Igjen: Tidlig Innsats for Livslang Læring (…and No One Was Left Behind: Early Intervention for Life-Long Learning). Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Education.

Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge (2008–2009). Government White Paper no. 11. Læreren. Rollen og utdanning (The Teacher. The Role and Education). Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Education.

Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge (2017). Lærerutdanning 2025 (Teacher Education 2025). Oslo: Norwegian Ministry of Knowledge.

Norwegian Research Council (2004). Norsk Pedagogisk Forskning. En Evaluering Av Forskningen Ved Utvalgte Universiteter Og Høgskoler. (Norwegian Pedagogical Research. An Evaluation of the Research in Selected Universities and University Colleges. Oslo: Norwegian Research Council.

Norwegian Research Council (2013). Nasjonal Forskerskole for Lærerutdanningene (NAFOL)- En Utvärdering Efter Halva Tiden. (National Research School for Teacher Education (NAFOL)- An Interim Evaluation. Oslo: Norwegian Research Council.

Norwegian University of Science and Technology [NTNU] (2009). Nasjonal Forskerskole for Lærerutdanningene (NAFOL) (National Research School in Teacher Education-NAFOL). Oslo: Norwegian Research Council.

OECD (2005). Teachers Matter: Attracting, Developing and Retaining Effective Teachers. OECD Publishing.

Østern, A. L., and Smith, K. (2013). “Response of the National Graduate School for Teacher Education NAFOL, to the call for a more research based teacher education in Norway,” in Teacher Education Research between National Identity and Global Trends, eds A. L. Østern, K. Smith, T. Ryhaug, T. Krüger, and M. B. Postholm (Trondheim: Akademia Publishing), 13–28.

Sannino, A., Engeström, Y., and Lemos, M. (2016). Formative interventions for expansive learning and transformative agency. J. Learn. Sci. 25, 599–633. doi: 10.1080/10508406.2016.1204547

Smith, K. (ed.) (2018). Norsk Og Internasjonal Lærerutdanningsforsking. Hvor Er Vi? Hvor Skal Vi Gå? Hva Skal Vi Gjøre nå? (Norwegian and International Teacher Education Research. Where Are We? Where Do We Want to Go? What Shall We Do Next?) Norwegian and English. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Smith, K. (ed.) (2020). Value and Validity in Teacher Education Research. Norwegian and English. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Smith, K., and Flores, M. A. (2019). The Janus faced teacher educator. Eur. J. Teach. Educ. 42, 433–446. doi: 10.1080/02619768.2019.1646242

Statistics Norway (2019). Gjennomføring Ved Universitet og Høyskoler (Completion by Universities and University Colleges). Oslo: Statistics Norway.

Sunde, J. I. (2020). “Alle skulle hatt en forskerskole». Ein kvalitativ studie av tidlegera stipendiater sine erfaringer med forskerskulen NAFOL. («Everybody should have a research school». A qualitative study of NAFOL alumni’s experiences with the NAFOL Research School),” in Validity and Value of Teacher Education Research, ed. K. Smith (Bergen: Fagbokforlaget).

Sunde, J. I. (2017). “Alle Skulle Hatt en Forskerskole». Ein Kvalitativ Studie av Tidlegera Stipendiater Sine Erfaringer Med Forskerskulen NAFOL. («Everybody Should Have a Research School». A Qualitative Study of NAFOL Alumni’s Experiences with the NAFOL Research School). Master thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen.

Vanassche, E., and Kelchtermans, G. (2016). Facilitating self-study of teacher education practices: toward a pedagogy of teacher educator professional development. Prof. Dev. Educ. 42, 100–122. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2014.986813

Vattoy, K. D., and Smith, K. (2018). “Developing a Platform for a Research-Based Teacher Education,” in Norsk og internasjonal lærerutdanningsforsking. Hvor er vi? Hvor skal vi gå? Hva skal vi gjøre nå? (Norwegian and International Teacher Education Research. Where are we? Where do we want to go? What shall we do next?), ed. K. Smith (Bergen: Fagbokforlaget), 17–44.

Keywords: expansive learning, teacher educators, research-based teacher education, doctoral education, research-school

Citation: Smith K (2020) Expansive Learning for Teacher Educators- The Story of the Norwegian National Research School in Teacher Education (NAFOL). Front. Educ. 5:43. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2020.00043

Received: 08 February 2020; Accepted: 01 April 2020;

Published: 28 April 2020.

Edited by:

Cheryl J. Craig, Texas A&M University, United StatesReviewed by:

Auli Toom, University of Helsinki, FinlandJoseph Samuel Backman, Alpine School District, United States

Copyright © 2020 Smith. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kari Smith, kari.smith@ntnu.no

Kari Smith

Kari Smith