Transcribing and translating forensic speech evidence containing foreign languages—An Australian perspective

- Translating and Interpreting, Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology (RMIT University), Melbourne, VIC, Australia

There is a growing body of literature on forensic transcription of covert recordings obtained by clandestine law enforcement operations. Due to the nature of these operations, the quality of the recordings, particularly those obtained by planting listening devices in a car or a house, is often extremely poor. When tendering such recordings as evidence in court for prosecuting an alleged crime, a transcript will often accompany the recording to assist the triers of fact (i.e., judges and jurors) to hear better. In the context of multilingual and multicultural Australia, often such forensic recordings may contain languages other than English, and therefore a translation into English is required to facilitate understanding of the verbal exchanges in the recording. Little is known, however, about the people engaged by law enforcement to undertake these forensic translation tasks, what qualification and training they possess, how they carry out the tasks, and if there is a system to safeguard the quality and reliability of their translation output. This paper reports on an online survey conducted in Australia on professional interpreters and translators who have been engaged to perform this type of work. Descriptive statistics and thematic analysis of text answers provide a qualitative account of the status quo which has not been documented before. Deficiencies of the current practice and its associated risks are identified. Recommendations are proposed as the first step to address the issues identified.

1. Introduction

Law enforcement agencies at times need to engage in clandestine operations to obtain private communications to solve or prevent crimes. In an increasingly globalized world where crimes do not observe national or linguistic boundaries, covert recordings law enforcement obtain often contain foreign languages. Australia is a case in point. Professional translators and interpreters are, therefore, often engaged by law enforcement in these situations to overcome language barriers, thereby allowing investigators to carry out their investigative tasks and/or to prepare forensic linguistic evidence for court trials. For investigative purposes, professional interpreters may be employed to listen to live or covertly recorded telephonic communications and asked to provide investigators with either the gist or a full interpretation of the exchanges under surveillance; they may also be asked to identify matters of interest or scour for specific items of information instructed by the investigator. For evidentiary purposes, although the actual recording is regarded as the primary evidence and the transcript as secondary (Gilbert and Heydon, 2021), triers of fact (i.e., judges and jurors) must rely on the translation into English of the original utterances in the audio to access the meaning of the exchanges spoken in a foreign language that they do not understand.

This paper reports on an online survey conducted in Australia on the experiences of translators and interpreters involved in forensic transcription and translation (FTT) for law enforcement for both investigative and evidentiary purposes. It provides insights into this under-researched interdisciplinary area of criminal justice and translating and interpreting (T&I) studies to establish an understanding of current practice and issues which need urgent attention.

2. Background

Wiretapping operations conducted by law enforcement can be categorized into two macro-types: telephone intercepts, which are achieved by telephonic listening interventions, and environmental recordings, which are made by planting listening devices in the environment of the targeted speaker (Fraser, 2014; Romito, 2017). It should be noted, though, that with the advancement of communication technologies, the former has now become more relevant to interceptions of private messages via mobile phone, Voice Over Internet Protocol (Butterfield et al., 2016), social media post, or email. The audio quality of the latter (i.e., environmental recordings such as the bugging of a house or a car) is normally extremely poor (Fraser, 2017), “to the extent that, without prior knowledge of the contents, few if any words can be clearly identified” (Fraser and Stevenson, 2014; p. 206). These covert recordings may be used to serve two purposes: investigative or evidentiary (French and Harrison, 2006; Haworth, 2010; Fraser, 2014). For the former, information from the covert recording is used to help law enforcement “uncover the facts surrounding an alleged crime” (Fraser, 2014; p. 8), for example, when the persons of interest will be meeting, where, and to do what. If successful, the outcome of the operation becomes evidence in the court trial (Fraser, 2014). In these situations, when investigators are faced with poor quality covert recordings, they can combine their insights on the case at hand and form an educated guess about what is possibly being said in the unclear or indistinct audio, thereby deciding their next action or the direction they should take in their active investigation. They do not need to justify to anyone how they “interpret” the indistinct audio to reach what they think the utterances are. On the other hand, when a case enters legal proceedings and if the covertly obtained recordings are going to be used by law enforcement as evidence to prove guilt, the recordings become forensic speech evidence and serve evidentiary purposes. The recordings may “capture a criminal offense being committed or can contain incriminating (or exculpating) material, including admissions of guilt, involvement, or knowledge of criminal activity” (Love and Wright, 2021; pp. 1–2). Fishman (2006) aptly describes the evidentiary value of conversations captured in covert recordings:

Few, if any, forms of evidence are likely to be as probative—or as devastating. We see this most often in criminal cases: rather than rely on the testimony of witnesses who may be vulnerable to various forms of impeachment, a prosecutor simply allows a defendant's words [caught on recording] to speak for themselves. (p. 475)

Fishman (2006) further asserts that a jury's ability to use such evidence depends on two qualities of the recording: audibility and intelligibility. The former relates to whether the listener can hear what is on the recording, while the latter is about whether the listener is able to understand what is being said. When covert recordings with poor audibility and/or intelligibility are presented in Australian courts, the law allows the jury to be provided with a transcript prepared by police to help jurors hear better relevant utterances and attribute each to a speaker (Fraser and Loakes, 2020). These indistinct recordings are often transcribed by police detectives or officers involved in the case, or what Fraser (2014) calls “involved transcribers” (p. 12), with no training in transcription at all.

Transcription is highly complex, meticulous, and onerous even for clear recordings (Jenks, 2013). For covert recordings, it is clearly not the intention of the speaker to be (over) heard by a third person, therefore the possible “messiness” of the talk unlike a monitored talk, e.g., a courtroom exchange or police interview, which will be much more orderly. Transcribing covert recordings is particularly challenging because the “ground truth,” that is, the accurate, incontestable knowledge of what was really said, is not available (Fraser and Loakes, 2020; p. 416). It is, therefore, problematic that the police transcribers may be “hindered by having contextual information that is potentially unreliable (having not yet been tested by the trial process)” (Fraser and Loakes, 2020; p. 417). Using untrained police officers who have a vested interest in the influence of the transcript on a case gives rise to potential inaccuracy (Love and Wright, 2021). There has been growing concerns about unreliable transcripts and their priming effect on jurors. Empirical evidence has shown that once triers of fact are presented incorrect and misleading transcripts, they are unable to unseen them (e.g., Fraser et al., 2011; Fraser, 2014, 2021, Fraser and Stevenson, 2014), or in Fraser and Loakes (2020) term, to “reset their perception to give equal consideration to alternative interpretations” (p. 418), and their confidence does not seem to diminish considering their “inability” to hear (e.g., Fraser, 2018; Fraser and Kinoshita, 2021). Unreliable transcripts, therefore, give “extraordinary privilege for the police interpretation of indistinct covert recordings” (Fraser and Loakes, 2020; p. 418) and increase the risk of innocent people being convicted and the guilty set free (Gilbert and Heydon, 2021).

What is described so far is also true when the covert recordings contain languages other than English (LOTEs) in the Australia context. In such situations, regardless of the audio quality being acceptable, poor, or indistinct, law enforcement is unable to transcribe nor translate the audios themselves. Little is known about who perform FTT tasks, what translation approaches are adopted, and how the quality and reliability of the translation into English is attained and assessed. This paper intends to address this gap of knowledge.

3. Literature review

Scholarship on transcribing covert recordings containing LOTEs and its implications is scant. As a starting point, such FTT tasks obviously must be undertaken by people who are speakers of the same foreign language as in the audio, and in Australia and other Anglophone criminal jurisdictions, interpreters and translators are often engaged; similarly, in European countries such as Belgium “sworn translators-interpreters” are engaged to provide the service for legal wiretapping (Salaets et al., 2015), i.e. intercepted communication, while in Switzerland “intercept interpreters” are engaged (Capus and Griebel, 2021; Capus and Grisot, 2022; Capus and Havelka, 2022). American legal interpreting scholars González et al. (2012) regard FTT as “one of the most demanding and rapidly growing areas of legal interpretation” (p. 965), and therefore devote an entire chapter to this topic in their seminal volume, Fundamentals of Court Interpretation: Theory, Policy, and Practice. They assert that the primary purpose FTT serves is to “provide an impartial, accurate, complete, legally equivalent, and contextually sound transcription/translation from the SL [source language] to the TL [target language]” (González et al., 2012, p. 991), while advocating the need for specialized training for FTT in response to the hybrid nature of a task that calls for interpreting, translating, and task-specific skills (see also Mikkelson, 2016). Sections 3.4 and 3.5 will cover the scholarly views about the nature of the work and the required skills and knowledge.

It should be mentioned that González et al. (2012) chapter on FTT has a different focus from the current paper. Their chapter is mostly concerned with transcribing and translating police interviews in the US, both custodial and noncustodial, where “putative interpreters” [Calmeyer, 2010, as cited in González et al. (2012); p. 967] are used, that is, where police officers who have unspecified Spanish language competence double as interpreters, therefore creating miscommunication and harming the interviewee's defense. In these circumstances, T&I practitioners do not deal with covert recordings of suspected criminal activities. Rather, they deal with police interview recordings, which are generally of better audio quality, and all participants to the interview are aware of the recording taking place (i.e., overt recording). However, regardless of whether recordings are overt or covert, the principles that González et al. (2012) advocate—to produce quality and reliable FTT—are equally applicable. This will be explicated in Sections 3.1–3.3.

It is also worth pointing out that the emerging European literature referenced before approaches the activities undertaken by “sworn translators-interpreters” (in Belgium) or “intercept interpreters” (in Switzerland) from a slightly different perspective. It is rightly concerned about how T&I practitioners' agency and work practices in the law enforcement operation, investigation, and prosecution phases, therefore their “visibility” or, rather, “invisibility” which leads to ethical and ontological questions in their respective inquisitorial systems. While the current paper focuses more specifically on the probity, quality, and reliability of forensic speech evidence used in the adversarial criminal justice system in Australia accompanied by translations produced by T&I practitioners, the commonalities in relation to the challenges and issues faced by Australian practitioners will be remarked upon where appropriate.

3.1. Two-step process

According to González et al. (2012), FTT should be a two-step process: first, producing an orthographic transcript of the original language caught in the recording; and then translating the transcript into the target language for forensic purposes (English in the case of the US). This is because that “without the critical step of transcribing the speech event into textual form, an accurate and verifiable translation is not possible” (p. 1006). Whether such an approach is followed by T&I practitioners is a separate matter, and the survey reported in Section 5 will shed light on the reality in Australia.

The starting point of the judiciary is often that all transcripts provided by the prosecution (whether in English or translation into English from a foreign language) are accurate and fit for purpose for trials (Gilbert, 2014), and from there the defense can attempt to create uncertainty in trials about the meaning alleged by the prosecution (González et al., 2012). Although, as mentioned before, the primary evidence is the audio and the transcript is secondary (Gilbert and Heydon, 2021), in reality, audio recordings are not necessarily played in court trials for practical reasons: if the audio is in English, reading the transcript is easier for the triers of fact to visualize the words, as opposed to listening to ephemeral sounds in the recording; and if the audio is in a foreign language, there is even less incentive to play it, since triers of fact will have to rely on the translation anyway. Either way, jurors rely heavily on the transcript, unless there is a particular point the prosecution or the defense attempt to make about the recording, in which case the audio may be played. If the utterances in a foreign language in the translation provided to the jury are disputed by the defense, often the court interpreter may be asked to listen to the recording on the spot and provide their version of translation for counsels to further explore and confirm meaning. In theory, the prosecution will make the transcript available to the defense before trial for the defense to check and mount challenges to its accuracy; if it is a translation, the defense can employ their own T&I services to verify and rectify points of differences to arrive at an agreed version with the prosecution. However, in reality, the defense often does not have the resources nor sophistication to undertake such checking. In the current system, no one really knows if the translation produced by T&I practitioners is accurate (Gilbert, 2014). In the US context, González et al. (2012) assert that once the translation is entered into evidence without objection, “defense attorneys lose the opportunity to appeal, challenging the reliability of the evidence, and the LEP [Limited English Proficient] defendant faces a greater risk for wrongful conviction” (p. 977). According to Capus and Griebel (2021), intercepted communication is often not transcribed first in Switzerland either, and “different procedures seem to be utilized within the Swiss cantons and police stations regarding whether a transcript is produced in the original language before translation” (Capus and Havelka, 2022; p. 1830). The recommended two-step process engenders a better audit trail (Gilbert and Heydon, 2021) for the accused to “determine whether the transcript accurately corresponds to the recording [in the original foreign language], even though he/she may not be in a position to evaluate the accuracy of the translation” [National Association of Judiciary Interpreters and Translators (NAJIT, 2019; p. 5)]. González et al. (2012) hold that the constitutional rights of the defendant are infringed when they are only provided with a translation into English without a transcript of what they are alleged to have said in the foreign language in the recording.

3.2. Verbatim orthographic transcript

In relation to producing orthographic transcript in LOTE, that is the first step of the two-step process for evidentiary purposes, scholarly views converge on Fishman's (2006) “mirror the tape” rule (pp. 494–495), which is to include what can actually be heard on tape. Further, González et al. (2012) assert that “all the linguistic, sociolinguistic, pragmatic, and discoursal elements of the speech event” (p. 992) in the audio should be transcribed, and that “clearly discernible paralinguistic features, such as pauses, changes in voice, tone, volume, silences or hesitations, hedges, false starts, or interjections, also need to be documented via the application of the legend system” [González et al., 2012; p. 992; see also Mikkelson (2016)]. The suggested legend system referred to is intended to enable the transcript reader to reconstruct meaning more holistically (Mikkelson, 2016) when there are “paralinguistic or sociolinguistic elements that may not be explicitly stated, but are present and do carry meaning” (González et al., 2012, pp. 1039–1041). Appendix 1 shows the LOTE transcription guidelines González et al. (2012) propose. The conventions and symbols they recommend using largely conform with the Jeffersonian transcription system (Jefferson, 2004) used to transcribe English discourse.

It should be noted, though, that transcripts can never be a full representation of spoken discourse, which comes with an almost infinite number of nuances and layers of social interaction due to limitations of space (Jenks, 2013), therefore the possibility and practicality of including all details as suggested by González et al. (2012). Considering the purpose of the transcript (and its subsequent translation) advocated by Capus and Griebel (2021) holds much truth. There should be communication between the transcriber and the user of the transcript to agree on the desired level of details required for the transcript or when/where detailed discoursal information is required, as this has implications for the time it takes to produce the transcript, therefore the cost.

3.3. Translation of transcript

Once the transcript captures all necessary linguistic, paralinguistic, and extralinguistic elements (if required), an impartial, accurate, complete, legally equivalent, and contextually sound translation can then be produced, without editing, summarizing, deleting, or adding any information, while conserving the non-English speaker's language level, style, tone, and intent (González et al., 2012). González et al. (2012) go so far as to suggest that T&I practitioners should, in producing the translation, clarify in a footnote when “gesture, feature, or utterance is culturally bound or contains significant linguistic or sociolinguistic information” (p. 992).

Gilbert (2014; Gilbert and Heydon, 2021) documents various FTT issues from Vietnamese into English in drug related cases heard in the Victorian County Court in Australia. Notably the Vietnamese term “ấy”, which is an exophoric or anaphoric reference word similar to the term “it” in English, was translated numerous times in the telephone intercepts as “thingy”. The Crown alleged that “thingy” was a coded word for drugs. Yet there is no evidence in the original utterances that such a coded word or any other word exists that can be translated as “thingy” within the context of the communication. According to González et al. (2012), a literal translation approach in these high-stake situations should be used, because “the potential for prejudice is too great” (p. 991), and they recommend that the meanings of coded words be left to be professed in testimony as expert opinion by police.

The National Association of Judicial Interpreters and Translators (NAJIT, 2019) in the US endorses the two-stage process of FTT, namely, transcribing in the original language first before translation. They acknowledge FTT to be very time-consuming and exacting, citing an industry standard of up to one hour of transcribing work for every minute of conversation in a forensic recording, which does not include the subsequent translation. NAJIT (2019) further asserts that given all that is at stake in a criminal matter, there is no justification for cutting corners (see also Mikkelson, 2016; p. 69). It should be noted that in reality this NAJIT proposition will be hard to attain since the FTT costs will be prohibitive. Maintaining a balance between readability and accuracy (Tilley, 2003) should be achievable, though, through communication between the transcriber and person commissioning the work as suggested in the previous section so the FTT outcome is adequate to serve the intended purpose.

3.4. Intermodal translation

FTT is fundamentally a “translational activity sui generis” (Capus and Havelka, 2022; p. 1817), in that it entails an auditory input in the SL and a written output in the TL, which distinguishes it from conventional translation (text input to written output) and conventional interpreting (auditory input to oral output). Influential Russian linguist Jakobson (1959) delineates three ways of deciphering verbal signs:

(a) intralingual translation or rewording, an interpretation of verbal signs by means of other signs of the same language; (b) interlingual translation or translation proper, an interpretation of verbal signs by means of some other language; and (c) intersemiotic translation or transmutation, an interpretation of verbal signs by means of signs of nonverbal sign systems. (p. 233)

This Jakobson's framework is insufficient to describe the hybridity of FTT activities. Israeli translation theorist Toury (1994/[1986]) further delineates translation under Jakobson's typology into intersemiotic versus intrasemiotic, where the latter (which FTT applies) is further divided into intrasystemic (i.e., intralingual) translation versus intersystemic (i.e., interlingual) translation.

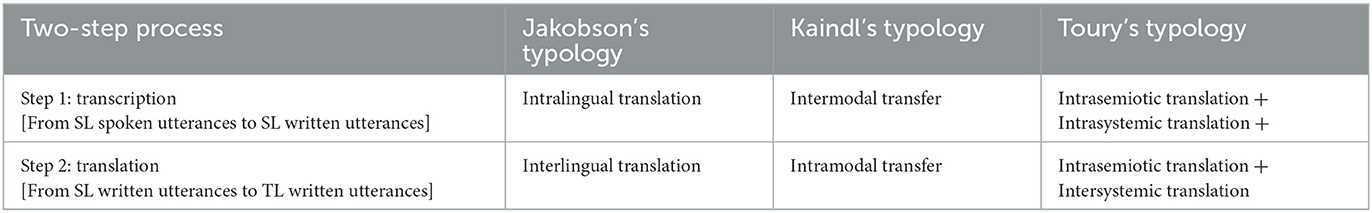

The two steps of FTT advocated by González et al. (2012) involve acts of translation: the first step corresponds to Jakobson (1959) intralingual translation as well as Toury's intrasemiotic and intrasystemic translation, while being a kind of intermodal transfer (Kaindl, 2012), i.e., from auditory to written. The second step is in Jakobson's term interlingual translation as well as a kind of intramodal transfer (Kaindl, 2012), i.e., both input and output are in written form, while it is intersystemic in Toury's term. Table 1 summarizes the two-step transcribe–translate process and how they correspond to the different translation typologies.

The first step of the two-step process—is no different from monolingual transcription from spoken English to written English which, as Fraser (2022) aptly points out, requires interpretation and decision-making by both its creator and by its end-user, and that no transcript is ever “the” transcript, rather “a” transcript. In this sense, Orletti and Moriottini (2017) also acknowledge that the transcriber “inevitably makes selections” (p. 3), and therefore transcription is never a neutral action. T&I practitioners engaged to undertake FTT, like other types of interlingual transfer tasks, must have not only linguistic competence, but also intertextual, psychological, and narrative competence (Eco, 2001; p. 13). Available T&I scholarship does not have applicable models as yet for the intermodal operation of transcribing covert recordings (i.e., Step 1 in Table 1), nor interlingual translation from the foreign language in the transcript into English (i.e., Step 2 in Table 1), which should be the direction of future scholarly endeavor.

3.5. Required skills and knowledge for FTT

Bucholtz (2007) asserts that transcription is “a sociocultural practice of representing discourse” (p. 785), while Orletti (2017) describes it as “extracting chunks of a social interaction and fixating its ‘flowing' on a printed page … [by doing so, turning] those chunks into movable items that can be repositioned into other contexts” (p. 13). Italian scholars Paoloni and Zavattaro (2007; p. 139) remark on a lack of academic curriculum for training experts in dealing with intercepted telephone calls and undercover recordings, while Bellucci (2022, as cited in Orletti, 2017) echoes the same deficiency of specific training for both police professionals and experts of forensic transcription. To successfully perform forensic transcription (intralingually), Orletti (2017) states that one must possess linguistic, phonetic, dialectological, sociolinguistic, and technological competencies.

Considering FTT as a hybrid translational activity sui generis, the required knowledge and skills for T&I practitioners to undertake FTT, therefore, comes into question, as is explicated in the NAJIT (2019) position paper on FTT:

Not all interpreters are adept at transforming the spoken word into written text with the accuracy required in the legal setting. By the same token, professional translators may lack the training to accurately transform live recorded extemporaneous speech into written form. Translators may also not be familiar with non-standard usage and jargon, as well as not being accustomed to documenting the errors and misspeaks that often color the speech of individuals with limited or no formal education. Consequently, not all translators can successfully render an authentic and accurate forensic transcription translation. (pp. 1–2)

González et al. (2012) observe that the field of FTT remains a “largely ungoverned, unlicensed, and nonprofessional practice,” arguing that “until there is acceptance of this field as a subspeciality of interpreting and the establishment of credentialing or certification, there will be great variability in product quality” (p. 980). The authors go so far as to suggest a master-level FTT specialist, who is certified for their higher level of skills and expertise with additional knowledge, experience, and academic credentials, and who not only provides routine FTT services, but also specializes in reviewing FTT work performed by others when FTT evidentiary materials are challenged by any of the parties, or when the judge orders ad hoc independent review or independent transcription/translation.

In addition to primary skills of language proficiency, cultural knowledge, and linguistic knowledge as well as an understanding of forensic linguistics (Kredens et al., 2021) which is not dissimilar to competencies required for monolingual transcription, González et al. (2012) also propose the following five personal traits for T&I practitioners to possess for FTT tasks:

1. A highly attuned, perceptive ear

2. Analytic and problem-solving skills

3. Research skills

4. Organizational skills

5. Attention to detail

It appears that apart from the first trait, which is more specific to the task of transcription, the rest tend to be soft skills that are generic to a lot of professions.

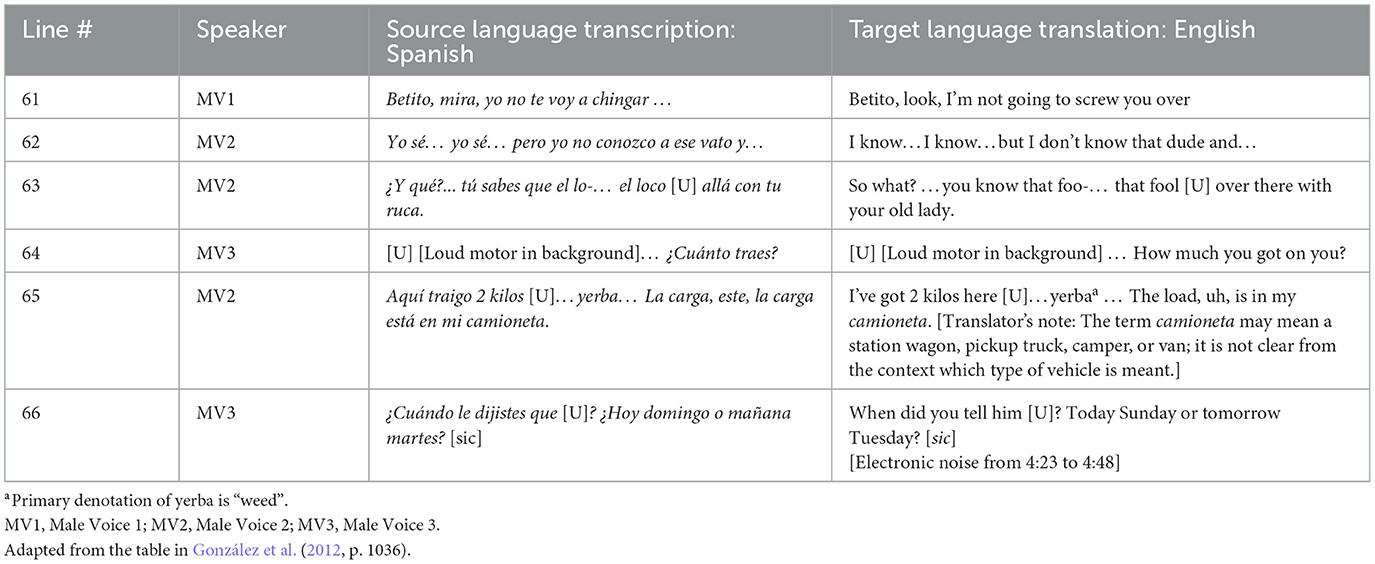

3.6. Recommended FTT formatting

González et al. (2012) recommend a four-column presentation of FTT (as shown in Table 2) in order to be clear and accountable, a recommendation endorsed by NAJIT. The first column denotes line numbers for easy reference. The second column attributes the speaker to the utterance transcribed in the line and is distinguished by male or female voices represented as MV1 (male voice 1) or FV1 (female voice 1); and as far as the transcriber can tell whether the voice belongs to the same speaker in the same recording, or a different voice, therefore MV2, MV3, and so forth, or FV2, FV3, and so forth. The third is the verbatim orthographic transcription of the SL utterance, and finally the last column is the translation from the text in the third column.

3.7. Translation of text messages

With the advancement of communication technologies and the popularization of computer-mediated communication (CMC)—defined as text, images and other data received via computer (Wainfan and Davis, 2004; p. 4) either synchronously (e.g., online chat or text message) or asynchronously (e.g., webpage or email) (O'Hagan and Ashworth, 2002), private messages have become increasingly important in crime investigations. This has necessitated the engagement of translators to assist in converting such communications in the text format from a foreign language into English in a forensic context. According to Capus and Havelka (2022), intercept interpreters in Switzerland translate text messages as part of their work, together with live and recorded conversations. Text messaging, as a form of CMC, is a unique way of communicating, which manifests in written and visual structures, but embodies the characteristics of spoken discourse with all the elements and complexities of oral communication; this hybrid nature lends itself to “finger speech,” in that it is as if the fingers speak the minds of the communicators (Cal-Meyer, 2016, para. 2). Similarly, live chats as another form of CMC are observed by O'Hagan and Ashworth (2002) to be like spoken discourse which are fraught with “anomalies such as misspellings and grammatical errors…[and are] characterized by the use of online jargon and topic fluidity” (p. 55).

In the Western Australia case R v Yang [2016] WASC 410 (Auslii, 2017), translations of text messages from Korean into English between a drug trafficking suspect with alleged accomplices came under question. The defense challenged a number of aspects of the translation of the text messages and argued that the approach taken by the translator was inconsistent with the AUSIT Code of Ethics in that a translator should preserve the “content and intent of the source message or text without omission or distortion” (AUSIT, 2012). Justice Fiannaca ruled that there were several deficiencies in the translator's evidence, including:

1. lack of translator's notes when translating a laughing emoticon into “ha”

2. lack of translator's notes when disregarding certain parts of the messages and clean up typographical errors in the messages, which could have been ambiguous

3. not reproducing all the laughing emoticons as were in the original text messages

4. repeated Korean expressive characters were translated into a single “oh” or “ah” sound, which lost its expressive characteristic

5. expressing an opinion about a conclusion to be drawn from a message (KordaMentha, 2018).

It is, therefore, important to note that the inaccuracies in the translation in this case led to limitations for the court to draw inferences from the affected messages, and the opinions provided by the translator outside of his field of expertise were manifestly disregarded (KordaMentha, 2018). His honor states that “the challenge [by the defense] … was not to the witness's [i.e., the translator's] impartiality, but to the accuracy of some of the translations and his methodology. More generally, it could be said that the challenge was to Mr. Y Lee's [i.e., the translator's] reliability as an expert” (Auslii, 2017, para 55). This case serves as a reminder for T&I practitioners to approach this type of forensic translation tasks with great caution and well-informed methodology, as the language in text messages comes with many challenges, according to Cal-Meyer (2016):

- linguistic uncertainties: e.g., grammatical inconsistencies and gaps; spontaneous use of abbreviations, onomatopoeias, alliterations, acronyms; spellcheckers altering the meaning of the message; limited use of discourse markers such as adverbs, conjunctions, prepositions, deictic pointers, and other referents of space, time, and persons/pronouns.

- pragmatic uncertainties: e.g., use of etomitcons, iconic symbols, visual representations familiar only to the texters; intermittent and interrupted conversations.

- cognitive uncertainties: e.g., fragmented and short speaker turns; whimsical ways to economize space on the screen; encapsulation or minimization of ideas, statements, propositions; limited use of cohesive devices; unclear anaphoric references; poor adherence to principles of relevance. Too long with no comments.

This type of translation, unlike translating conventional written text, was referred to as “transterpreting” by Ashworth (1997). Although he coined the term to describe the real-time translation output in the target language for live chats in what can be regarded as the prototype of today's online conference, except for the simultaneity required for “transterpreting”, the rest of the translation challenges in relation to the nature of online chats identified by O'Hagan and Ashworth (2002) are very similar to Cal-Meyer's (2016) observations above for translating text messages in a forensic context.

4. Methods

An online survey was designed to collect descriptive statistics and qualitative data to answer an overarching research question: what is the current state of service provision for FTT by T&I practitioners in Australia? The study is important to generate new knowledge to complement the growing body of literature on forensic transcription practice and its evidentiary value in criminal trials in Anglophone countries, which has so far focused on issues arising from monolingual audio materials. The three sub questions of the study are:

1. Who among interpreters and translators are engaged to undertake FTT and what is the required training and/or credential?

2. How do they perform their FTT tasks?

3. What have been their reflections about their FTT experience?

The anonymous and voluntary online survey received ethics approval from the university the author is based, and email invitations to T&I practitioners nationwide with an embedded survey link was distributed through four language service agencies having national presence as well as through the newsletters of the National Accreditation Authority for Translators and Interpreters (NAATI) and the Australian Institute of Interpreters and Translators (AUSIT). The precise size of the survey population is difficult to ascertain, due to the fact that not everyone practicing as an interpreter and/or translator holds a NAATI credential, particularly for low-demand and new-arrival languages in which there are very few or no NAATI-credentialed practitioners. However, the 13,178 practitioners currently holding some form of NAATI credential can be regarded as a reference point; they are reported to cover 147 languages, including the Australian Sign Language, and a further 38 indigenous languages (NAATI, 2021). The survey was open from April 2019 with a closing date extended from the original six months to the end of 2019. The survey questionnaire contains nineteen questions (see Appendix 2), eighteen of which are multiple-choice with free text spaces for the respondent to elaborate on the answer they chose and the last Question 19 is open-ended to elicit further voluntary contribution from the respondents on anything they wished to say about FTT.

Purposive sampling was achieved by the explanation in the email invitation, which stated the purpose of the survey and invited those who had done FTT assignments to self-identify and participate. A total of 356 questionnaires were returned via the university's Qualtrics platform from which the survey was administered. Although the response rate is only less than 3% of the population, it should be noted that not all languages are required for FTT, and that some languages are required more frequently than others. In other words, the actual population of the current study should be T&I practitioners who are involved in FTT. However, presently there is no way to ascertain this more precise population. What can be sure is that the response rate against this more precise population, had it been available, would be much higher than 3%.

Not all respondents answered all questions. As all questions yielded more than 315 responses, except for Question 15 which had 256 answers, it was decided not to exclude questionnaires which missed some questions in order to capture the respondents' contribution to the maximum. Number counts and their corresponding percentages for Questions 1 to 18 were generated by Qualtrics reporting facility, and each question has slightly different overall count depending on how many respondents skipped the question. Free text contributions for Questions 1 to 18 was analyzed using a deductive approach, considering they were specific to the questions asked, and the number of contributions for each question was not large, and thus manual count of relevant meaning units was more efficient for the purpose of further enlightening the quantitative data. On the other hand, the contributions entered for Question 19 were coded using an inductive approach (Braun and Clarke, 2006) using Nvivo 12. The author underwent the analysis in two phases by first reading through the contributions a few times to familiarize herself with the content, which enabled her to identify the central issues (Patton, 2002) and then document her initial thoughts and impressions. This phase was in keeping with the first three steps recommended by Braun and Clarke (2006) for thematic analysis: (1) familiarization with data; (2) generate initial codes; and (3) search for themes. The author then examined the initial themes emerged from the first phase to evaluate their connections, similarities, and difference. This phase reflected the next two steps by Braun and Clark's: (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes. Some meaning units were found to relate back to the specific questions and therefore were grouped with the questions to streamline the reporting. The results of the survey are presented in Section 5 below, followed by discussions based on the insights achieved.

5. Results

Of the 19 questions in the survey, Questions 1 and 2 were intended to form the profile of the respondents, which is reported under Section 5.1. Questions 3 to 17 were designed to build a picture of the FTT work practice in Australia. The statistics and insights from these questions were synthesized into seven topics and reported as sub-sections under Section 5.2. The only exception is Question 16 about practitioners testifying their FTT work in courts, which is presented in Section 5.4 separately. As a relevant enquiry but not strictly within the realms of FTT, Question 18 probed the respondents' experience in providing forensic translation services for text messages. This is reported under Section 5.3 separately. Lastly, Section 5.5 reports the three themes arising from the last Question 19 as an open invitation for further thoughts the respondents were willing to share about their FTT experiences.

5.1. Demography of respondents

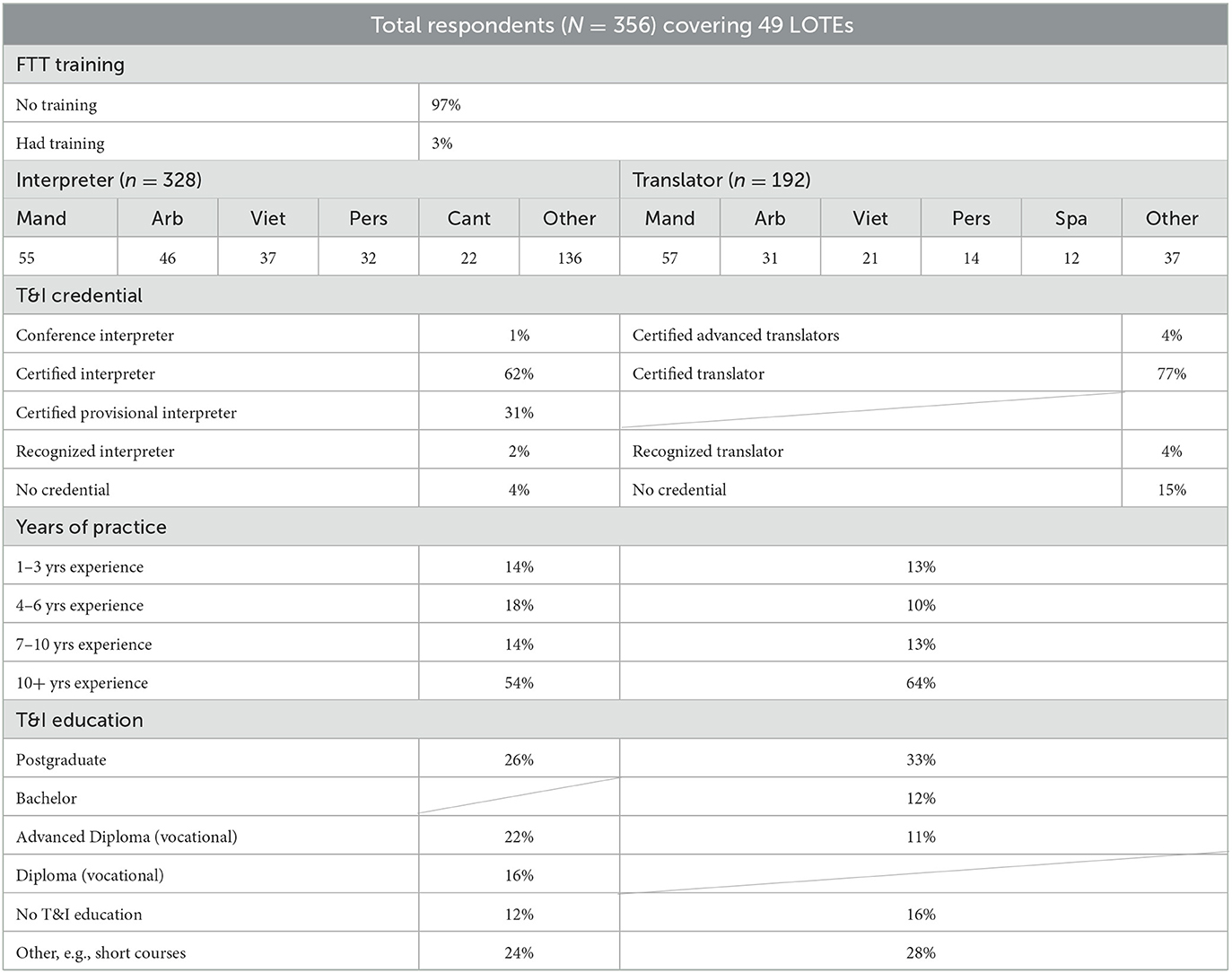

The profile of the respondents is, to a large extent, a mixture of translating and/or interpreting practitioners, who have some T&I related education and practiced at the professional level for a long time. As can be seen in Table 3 below, among the returned questionnaires, there were 328 who identified as interpreters and 192 as translators. The system is unable to identify the number of respondents who practiced both, although it is safe to say some of them are both interpreters and translators. Only 3% of the respondents reported to have had FTT specific training. A total of 49 LOTEs were reported by the respondents, with the top five languages being Mandarin (n = 55), Arabic (n = 46), Persian (n = 32), Vietnamese (n = 37), and Cantonese (n = 22). The top languages for those who self-identified as translators share exactly the same trend, with the exception of Cantonese being replaced by Spanish. This is because Cantonese is a dialect and Chinese is the language Cantonese speakers read when it comes to translation services.

The majority of the respondent interpreters were NAATI Certified Professional Interpreters (62%), followed by 31% being NAATI Certified Provisional Interpreters1 More than half of the respondent interpreters (54%) said they had more than 10 years of practicing experience, with the remaining divided among those who had 7–10 years (14%), 4-6 years (18%), and 1–3 years (14%) of experience. More than one in every ten participant interpreters (12%) had no T&I education at all, while just over a quarter (26%) had postgraduate T&I education, followed by 22% and 16% respectively having vocational training at the advanced diploma and diploma levels.

In relation to participant translators (some of whom may also be interpreters), a higher percentage (77%) were certified by NAATI at the professional level,2 with equally small proportions who reported themselves to be Certified Advanced Translators (4%) and Recognized Practicing Translators (4%). The remaining 15% of participant translators practiced without any credentials. Similar to the trend for the participant interpreters, the highest proportion of this cohort (64%) had more than 10 years of experience practicing, and those with no formal training were slightly more (16%) than the participant interpreters as well as those who had postgraduate education (33%), followed roughly equally those with a bachelor's degree (12%) and those who had vocational advanced diploma training (11%).

5.2. FTT work practice

5.2.1. Engagement pattern and work frequency

T&I practitioners were predominantly engaged in FTT assignments through interpreting agencies or directly from law enforcement (68%, n = 234). A further 25% (n = 87) offers their services directly as a sole trader, while the last 7% (n = 23) stated other ways of being engaged in FTT assignments but provided no further elaboration.

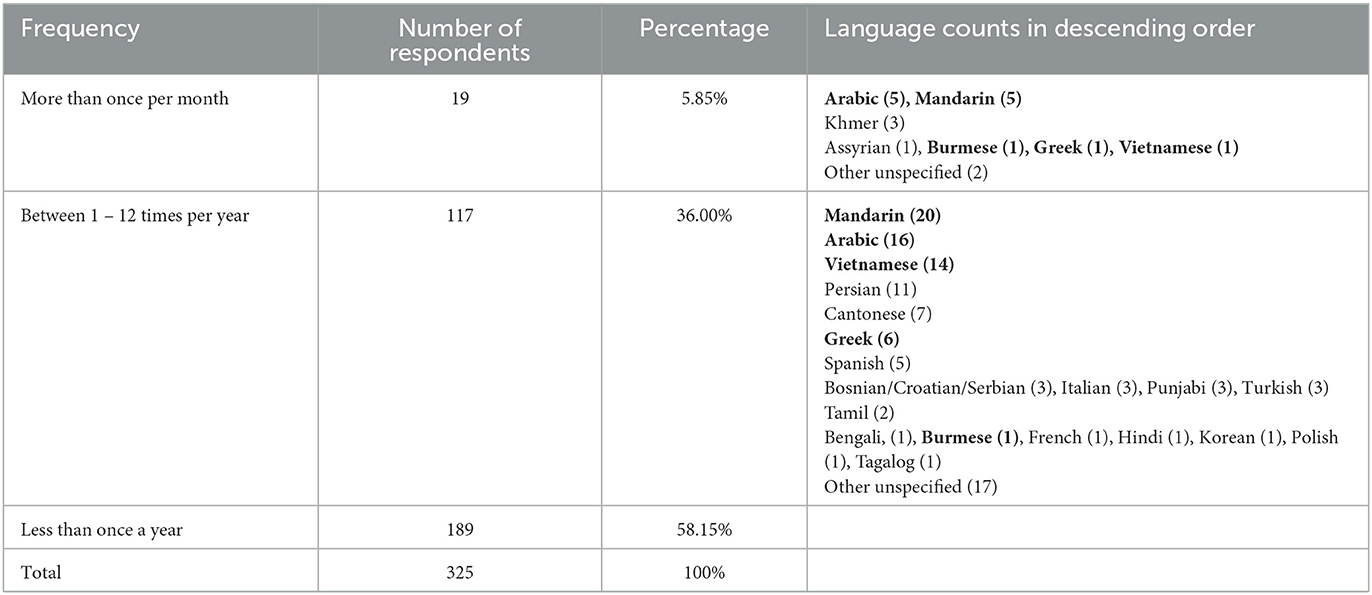

As is shown in Table 4 below, the frequency of FTT assignments appeared to be low, with 58% (n = 189) of the 325 respondents who answered Question 4 said they perform the task less than once a year. Only 6% (n = 19) said they do it more than once a month on average, while the remaining 36% (n = 117) reported doing between one to twelve assignments per annum. Those who undertook FTT assignments most frequently (i.e., more than once a month on average) cover seven languages, while those who did it not as frequently (i.e., between one to twelve times per annum) spread across 19 languages. The five languages which appear in both categories are bolded in Table 4, indicating possible higher demands of them for FTT assignments.

It is noteworthy that over 80% of the respondents (82%, n = 266) said that they usually work alone in FTT assignments, with only 32 respondents (10%) who said they normally work as part of a team. Only eight text answers were further provided by those in the latter category, of which five said they work as part of a “critical team,” or part of an “operation,” or with police officers, pointing to possibly work related to the investigative stage of cases. Only one mention in these eight text answers relates to “team translation,” pointing to the rare practice of engaging multiple T&I practitioners to check each other's work to ensure highest possible quality for transcription and translation. This reality is further corroborated by 83% of the respondents (n = 270) of Question 8 who said they were either never or rarely asked to check other practitioners' translation of forensic recordings.

5.2.2. Audio quality

Respondents predominantly described the audio quality of recordings for their FTT assignments as inconsistent, that is, sometimes good and sometimes bad (56%, n = 184), with almost equal proportions saying it is “normally good” (24%, n = 78) as opposed to “normally bad” (20%, n = 66). This points to the possibility that T&I practitioners work with both telephone intercepts, which normally have better audio quality, as well as covert recordings obtained through clandestine operations, which often feature extremely poor audio quality. The impact of bad audio quality is made clear in this participant's response: “Many a time, I had to listen to a section of the recording more than ten times. I was always worried about losing productivity in my attempts to create excellent quality output.” Overlapping talk in these environmental recordings was also commented on by respondents as increasing the challenging nature of FTT.

5.2.3. Briefing on assignments and provision of FTT protocols

When it comes to FTT work practices, a little over one third of the respondents (36%, n = 117) said that they did not usually receive a briefing about the case by the police officer in charge before they started translating the relevant forensic recording, while another roughly third (36%, n = 117) said that they were usually given a briefing. Information provided to them in the briefing was various, such as the nature and/or background of the case (e.g., “drug trafficking”), location, how the recording was done, people involved in the case, or, more bluntly, “how to pick up criminal activities” and “look for threatening evidence”. The remaining 28% (n = 92) had mixed experiences that is, a briefing was not consistently received. Further text responses from respondents in this group included: “sometimes [a briefing is provided], if it is not classified”; “sometimes … [I may have to] start straightaway, especially when I do phone call interpreting”; “I can access the warrant to obtain a full picture”; “vague info, e.g., ‘this is our crook, and he's calling his business partner”'; “number of people having conversation and mixing the languages”; and “a drug trafficking matter so that I need to understand some code words.” Respondents were further probed on whether they were usually briefed by the investigator about how to approach the translation of the LOTE utterances into English, to which two thirds of the respondents said no (66%, n = 213), for example, “they just say, there it is. Go ahead. Do your best. Talk to me about progress/problems”. Only 17% (n = 56) said yes, where the instructions they received included: “how to replay the recordings”; given “keywords” to look for in the recording; being advised to “type all the phone conversation in English”; “they want F and M for gender, or names if known;” “format [to use] and type of notes [to be inserted];” to produce “full [transcript] vs. ‘interesting part' only”; and being told “don't guess,” or “if … not clear or fragmented, leave them as they are.” The remaining 17% represented a mixture of experience by the respondents where instructions were not consistently received on how to produce the translation. The text answers revealed that “it depends on the nature of the assignment”; “they only require a summary in English”; “they advise, e.g., only focus on relevant parts, do a summary, [or] do a full translation etc.”; “told to do it verbatim”; “not much info. I feel I'm making up the rules as I go sometimes.” One participant offered invaluable insights about working for a particular law enforcement agency:

The syntax of my languages is different from that of English. Therefore, it's essential to listen to the full sentence before I can start translation. Sometimes, it may become helpful to a reader if I add the intended pronoun. For example, in my languages, a person would simply say, “How is/are?” This may be translated as “How are [you]?” or “How is/are [he/she/they]?” Unfortunately, the [name of agency] requires us to obtain special permission from a supervisor to write anything in square brackets, and generally, such permission is not granted! In my languages, there's only one pronoun for he and she. Sometimes, this creates a problem of gender recognition! Moreover, there are three different types of “you”—informal, formal, and honorable. The only punctuation marks that the [name of agency] allows are the full stop and a question mark! The use of an exclamation mark is discouraged.

5.2.4. Formatting instructions and transcribe-translate two-step process

In terms of formatting the translation for the forensic recordings, roughly two thirds of the respondents (64%, n = 205) said there were no instructions or guidance, with 19% (n = 62) saying they were advised about the required or preferred formatting. When probing what formatting instructions the respondents were given, they included templates or proformas provided in electronic formats by investigators, being told to follow a format that “should be admissible in court”; “put the accused and the other party in separate columns”; to “bold the words spoken in English by the individuals recorded”; requests to “identify who is speaking, e.g., speaker 1, speaker 2 etc.”; and to include time stamps. The majority of the respondents (72%, n = 236) translated the audio in a foreign language directly into English, with only 20% (n = 65) saying they first transcribed the foreign language in the forensic recordings before translating it into English. The remaining 9% (n = 28) of respondents reported a mix of the two practices. From the additional text the respondents entered, it is interesting to note that four respondents explicitly said that they wrote the words down first to enable a better translation into English, suggesting the utilitarian focus of this step for their translation process, rather than from the point of view of providing a traceable record for legal processes. A further three respondents said that they sometimes undertake this two-step transcribe–translate process, as exemplified by this response: “It depends on what the client wants. Sometimes I transcribe in the source language then translate and give them both copies or just translate directly.”

5.2.5. Speaker profiling

The respondents were also asked whether they had been asked to “profile” the speaker, i.e., “to give an opinion about what dialect they speak, or what region they might be from” as was explained in the question to ensure understanding. Most respondents either never (60%, n = 195) or rarely (14%, n = 45) found themselves in the situation, with only 4% (n = 13) saying they were asked all the time. The remaining 22% (n = 71) answered “sometimes”. Regardless of the answer they chose, respondents' written responses indicated that they were mostly asked to comment on the accent (e.g., north or south) and the variety of the dialect heard on the recording; which country (if the language is spoken broadly) or region the speaker was from; or what tribe/ethnicity, education level, or social status could be ascribed to the speaker. The following response illustrates the complexities encountered by practitioners when faced with such requests:

My language is Albanian. Albanian is spoken in the country Albania and also in Kosovo, where 99% of the population is Albanian. Albanian is also spoken in part of Macedonia, Greece and parts of Italy, where there is a large Albanian population. There are many dialects, and the times when I am asked about “profiling” the speakers, is when the criminals claim that they come from a certain region, but their dialect is from another region. It's a very complicated issue with Albanians.

On two occasions the text answers suggested that the practitioner was asked to discern which language was being spoken in the recording, for example, whether it was Russian or Ukrainian. No suggestion was made in the question as to whether practitioners should or should not respond to such requests, however, one participant wrote “[I told them] that they should get an opinion from a proper linguist or anthropologist who do [sic] have knowledge about the Indonesian dialects and accents,” and another participant remarked that such practice “can be fraught with danger/traps. Best not to jump to conclusions.” Similarly, another participant said “I try not to respond since such a response can be very subjective and may prejudice the case. I can usually tell the general region of the speaker but prefer not to be dogmatic.”

5.2.6. Voice identification

As a relevant question, respondents were also asked whether they had been asked to “identify” the speakers in a forensic recording, with further explanation in the question to ensure understanding: “that is, to say who they are by comparing their voices to other voices either within the same recording, or in a separate recording.” Similarly, more than eight out of every ten respondents said they were either never (77%, n = 251) or rarely (6%, n = 19) asked to perform such a task, while the remaining respondents sometimes (13%, n = 43) or always did so (3%, n = 11). Three text answers entered by respondents explicitly expressed that “I deny [sic] to do that giving the reason that I am not a voice expert”, or similar reasons. Only one text response explicitly embraced the task by saying “voice recognition is an important part of our work.” Surprisingly, one of the respondents who answered that they “rarely” performed such a task said in the text answer: “But we compare handwritten documents,” pointing to a risky and unprecedented request for T&I practitioners to act as forensic experts in comparing handwriting supposedly written in a foreign language.

5.2.7. Confidence level and time given to perform FTT tasks

When asked to rate their confidence in their FTT performance on a slider scale from 0 to 4 (0 = not confident at all, 1 = somewhat confident, 2 = moderately confident, 3 = very confident, and 4 = highly confident), the 256 respondents who answered this question returned a mean score of 2.69 (SD = 0.97), that is, between a moderate and very confident level of self-assessed performance.

To further understand the practitioners' FTT experience, they were asked if they were, on average, given the time, information, and resources they needed to do an excellent job in translating forensic recordings. More than seven out of every ten respondents said either “all the time” (32%, n = 105) or “sometimes” (41%, n = 132), leaving a minority who said “rarely” (16%, n = 51) and “never” (11%, n = 35). However, the text entered by one participant who answered “never” is concerning: “I have never been given a recording of adequate quality to transcribe or to translate, nor the background or context of the case which would enable me to understand the situation well enough to translate accurately”. Another participant who answered “rarely” was more understanding: “I think the police is trying to do their job as good [sic] as they can so I don't blame them.” Of the 22 text answers further provided by respondents who answered this question, the major themes are: time constraints for translation output impact on translation quality (5 mentions); poor quality of audio hampered the translation quality (4 mentions); and the lack of case related contextual information impedes the deciphering of the interaction on the recording (2 mentions). One text answer was particularly illuminating regarding the different capacities to rewind and re-play audios generated by different recording devices by law enforcement, pointing to possible limitations they have on FTT outcomes:

I find that the system used by the Federal Police, for example, allows you to slow down or speed up the recording and go back a few seconds and this is good when you need to re-listen to a particular part. However, recordings from listening devices use a different system that does not allow you to easily repeat a particular sentence and is very time-consuming.

5.3. Translation of text messages

Although not strictly in the realms of FTT as it does not involve transcription of recordings, respondents were asked if they had been engaged to translate text messages into English in forensic contexts, given the rising popularity of this means of communication. Over half (52%, n = 168) of the 326 respondents answered “yes.” Of the 112 text answers further entered by these respondents, there were 39 mentions of the task being “straightforward,” while 51 text answers related to the difficulties of the task. These challenges can be categorized into three broad groups:

1. Non-Latin-based languages using English alphabets in the text messaging without tone marks or diacritics, making it extremely hard to decipher meaning. The languages mentioned include Arabic, Chinese, Persian, and Vietnamese. As the following text answer explains: “Because there are tone marks in my language which are often missing in the text messages, the translator has to guess the meaning of the text which is sometimes not correct. The same spelling without tone marks has [several possible] different meanings.”

2. Use of slang/street lingo, sociolect/dialect/non-standard language, idiosyncratic language, abbreviations, coded words, emojis, swear words, ambiguous language, incomplete sentences, typographical errors, bad grammar, lack of punctuation. The following participant's response illustrates such challenges:

The issue is social media posts are often confusing, so you have to spend time to analyze the poster's language by scrolling through their previous posts to understand their language use … the Indonesian people are the king of abbreviations, they can come up with many different variations of non-standard acronyms or abbreviations. Those things might lead you to a completely different understanding.

3. Lack of context about the communication and lack of knowledge about the relationship between texters. As one participant put it: “The one big issue is in spoken Arabic. One statement can mean something and the exact opposite, for example the Arabic meaning of ‘you are kind' can mean both ‘kind' and ‘mean' depending on the context.”

5.4. Testify in court

Respondents were also asked if they were ever required to appear in court to answer questions from the prosecution and/or the defense about their translation of forensic recordings. Only 13% of the respondents (n = 42) said they were “sometimes,” with a further 1% (n = 3) saying they were asked “all the time.” The majority of respondents were either never (78%, n = 255) or rarely (9%, n = 29) required to do so. Of the 329 respondents who answered this question, 54 provided further text answers, ten of whom mentioned they had been subpoenaed but never had to testify in court either because they were eventually not called, the cases were settled before hearing, or the defense pleaded guilty. One of these ten respondents stated, “but I feel very nervous about the prospect of it.” For those who did appear in court, they were most often questioned about the accuracy of their translation and asked to explain or justify their choice of words, as was described by one participant: “Why this specific meaning of the word(s) has been used [but] not other meanings of the word, when the word has many meaning”. Similarly, another respondent stated that they were “queried on alternative possible interpretations,” while an observation was made by a further respondent: “Sometimes defense wants to use words of less impact.” The following response comprehensively summed up the challenging nature of FTT work and the prospect of having to swear in court on the accuracy of work which is generated from indistinct covert recordings containing information that is inherently hard to decipher:

It is hard to transcribe without context, and we often don't have enough context to make full sense of what is being said. For example, who are the speakers, their relationship, how many there are, etc. When you work on a case for a longer period, you start to learn more context from other recordings, but then that info can affect what you hear, or think you hear, on future recordings. It's a very difficult job and the idea of having to be cross examined on my work, particularly the decision about whether I am sure enough about what I heard to swear it in front of a court and therefore include it, or not include it in the transcription... well it's challenging!

In a similar vein, another participant described the dilemma of whether to commit to what they think they hear or to play it safe by stating the segment is indistinct, in case they must appear in court to defend the transcript/translation:

Very often the voice of the person whose phone is being intercepted is clear, but the interlocutor's voice is distorted. As an interpreter/translator you strain your ear, listen to the same part multiple times to make sure you can understand and translate, but sometimes this is just not possible. Or the lines are simply crackling or there is background noise, etc. When you produce a transcript/translation to be used in court, you need to be sure that it is correct, and very often I cannot be 100% sure that I'm hearing what I think I'm hearing. This is one added responsibility on the interpreter/translator and the dilemma arises as to whether to type what you think is being said or cover your back by typing “[indistinct]” if you know you won't be able to fully and satisfactorily back your choice in court if necessary.

Further, there was an honest revelation that “I do not like going to present myself [in court] as it is scary to be sitting there and the accused person seeing me and thinking I am working against them.” A similar statement was made by another participant: “Am I going to see the accused who made the calls [in the recording]? Will that put me in any kind of danger if they see who I am? I think more information should be provided to interpreters in such scenarios to put their mind at ease.”

5.5. Practitioner concerns

In closing the survey, respondents were given an opportunity to enter any free text they wish to comment on any aspect of FTT. Of the 72 text answers entered, the themes about poor audio quality and the lack of contextual information for cases were again dominant. Practitioners' concerns about the impacts of these limitations on their performance were palpable. In addition, a number of rare insights emerged which are categorized into the following three themes:

5.5.1. Working conditions and remuneration

The reality of the work is such that practitioners are mostly required to attend law enforcement offices in person due to data security and operational concerns. However, as one participant explains:

When you work onsite at police premises, you may not have the benefit of having a little chat here and there, stretching your legs, etc. so you end up doing many straight hours looking at the computer, straining your ear, without a break, sometimes surrounded by people you haven't met before, and even a toilet break is stressful when you have to ask someone to escort you, unlock doors, etc. and then someone has to come and log you into the system again, etc.

On rare occasions when practitioners were allowed to work offsite, it was not ideal either, as the following response illustrates:

I have the comfort of working at my own place; however, I lose the opportunity of having the agent/officer in charge at hand to ask any questions or to discuss any aspects that may arise, and the end result may be affected. Additionally, the audio software I use at home does not allow me to go back to an exact position in the recording or to slow it down to get more clarity.

A number of respondents commented on how they had to work under time pressure and the highly “complex,” “demanding,” “exhausting,” and “draining” nature of FTT tasks. One participant remarked that the task may look easy, but in fact is very hard and requires a lot of focus, highlighting the importance of incorporating linguistic as well as emotional elements in the transcripts. Other respondents raised the issue of remuneration: “Current pay offered does not compensate the effort and time put into providing a proper and best possible English version of forensic recordings”; language service agencies which deploy practitioners to such assignments “usually want the job done in a short time and pay minimum fees without considering quality and time required”; and “some agencies pay only the interpreting rate even for transcription.” A specific law enforcement agency was singled out by a participant as having tendered out FTT work to many language service agencies, and therefore every time a quote was requested for an assignment, numerous agencies competed for business basically on price, which “results in interpreters doing a taxing, complex job full of responsibility that is not commensurate with the pay.”

5.5.2. Need for translation guidance and standardized work protocols

Respondents strongly conveyed their views on the lack of translation guidance and work protocols for FTT assignments, which was also reflected in Section 5.2.2 above. One participant made the insightful observation that a translation accompanying the forensic audio evidence “by its nature [already] disrupts the evidence.” This participant went on to say that “police (and the judiciary) rarely understand this. When doing forensic transcription sometimes police cannot appreciate the complexities and implications for the evidence that the transcription constitutes. This should be of concern, understood and managed.” Another participant captured the dilemma well by asking the following question: when faced with ambiguity of meaning in forensic recordings or text extracts with little contextual information provided “should translators ask the professional for more context and discuss about word choices, or should translators offer all the likely possibilities in the translation for the judge/jury to decide which meaning it should be?”

In the absence of any explicit translation guidelines offered by law enforcement who require FTT services, it is also not known how practitioners deal with coded words and whether their neutrality is maintained. One participant stated that “once I transcribed a tape recording for drug trafficking. They mentioned red and white buttons hidden under the bed. I would not interpret what they were but just translated as it was.” Similarly, another participant also clearly articulated that for slang or coded words such as “a hit” or other drug terms, “these terms should be translated as they are. It is up to the law enforcer to work out what they mean and not the interpreter's job to conjecture.” There is also a comment which concurred with the two-step transcribe—translate process: “Transcripts are essential when doing this job. If the client is using several translators and comparing their translations, a transcript makes sure we all have the same primary source. Without a transcript this is a futile exercise.”

5.5.3. Need for specialist training and to define required competencies

Another strong theme emerging from the last free-text question in the survey is about the lack of specialist training nor clear definition of the competencies required for FTT. One comment remarked on the infrequent nature of the FTT assignments, and thus the need for the practitioner to “refresh, re-familiarize with equipment, program, find best work methods each time … [which] can be difficult and challenging to work efficiently and quickly to produce an excellent result. Training sessions would be extremely valuable.” Another comment suggested that “formal training as part of an advanced diploma or master's or as a separate long PD [professional development] should be offered.”

Practitioners rightly asked the question about who should perform FTT tasks and what credential should be required, for example, “I am not sure if interpreters are qualified to do transcription. Is transcription a translation? If yes, only certified translators should do it”; and “if I don't have the credential of LOTE into English, should I refuse the request of forensic translation when I serve as an interpreter?” These queries culminated in the following participant's comment: “I believe practitioners need to have both certifications in translation and interpreting in order to carry out this kind of forensic work.” Relevant to this, another participant suggested that NAATI should “test and award credentials for this area specifically, since I'm not sure that our current qualifications are applicable to the role.”

6. Discussion

This study has brought to light the current state of service provision for FTT by T&I practitioners in Australia by pursuing three enquiries: who does it, how they do it, and what they think about it. The landscape of this under-explored area has been mapped for the first time through the findings reported above.

6.1. Who does it

We have come to understand that a mixture of practitioners who are either interpreters, translators, or both were variously engaged for FTT assignments. Although large proportions of them had credentials awarded by NAATI, had some T&I education, and were relatively experienced practitioners, very few of them had any FTT specific training, which is currently not widely available, if at all. The two-step process recommended by best practice FTT (see discussion in 3.1) points to two areas of specialist training required: transcription (from spoken LOTE to written LOTE), and translation (from LOTE into English). The need for training for the former is no different from monolingual settings, which has been advocated by scholars (Fraser and Stevenson, 2014; Romito, 2017; Fraser and Loakes, 2020; Fraser, 2021, 2022) in order to achieve accuracy and reliability in forensic contexts. The current study reveals the fact that the majority of the respondents undertook very infrequent FTT assignments, and unlike other areas such as community interpreting for healthcare, education, or social services, FTT does not constitute their bread and butter. On the one hand, it hampers developing expertise in this line of work as was reported in Section 5.5.3. However, this also makes it possible to focus on the higher-demand languages and consider prioritizing them for targeted training to start cultivating expertise in this specialist branch under legal interpreting and translation which has so far been neglected. This should improve the status quo where only 3% of the respondents had ever received relevant FTT training. If we disregard the row showing the lowest work frequency in Table 4, (i.e., those who did FTT assignments less than once per annum), Arabic and Mandarin no doubt feature most prominently in the other two categories of higher frequency, pointing to the possibility of recruiting selected practitioners from these two languages as the candidates for targeted training. Languages such as Burmese, Greek, and Vietnamese which appeared in both categories, may be considered when training can be expanded for larger language coverage. However, further triangulation of data on high-demand languages from law enforcement and language service agencies will be desirable to confirm if these languages reflect their demand profiles, or whether adjustments to add or take out certain languages are necessary. This is because the work frequency probed in the survey was self-reported, and there was no definition given as to what constitutes an assignment. For example, whether respondents regarded a long case spanning many weeks of FTT work at a law enforcement office as one assignment or several days of single assignments, is unknown, and therefore some languages of high demand might be missed or appear to rank lower in this study, or vice versa.

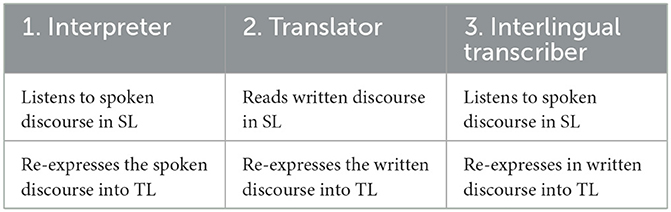

Although the respondents' average confidence level of their self-assessed FTT performance was between moderate to very confident, one may posit that the lack of training could manifest as a false sense of confidence and an ignorance of risks. Those who expressed unease about performing FTT when they are not credentialed translators from LOTE into English were right to question the probity. Interpreters are language professionals who specialize in listening to spoken discourse and converting it into spoken discourse in the TL (i.e., column 1 in Table 5 below), while translators specialize in reading written discourse and converting it into written discourse in the TL (i.e., column 2 in Table 5). Interlingual transcribers, however, listen to spoken discourse in the SL, but produce written discourse in the TL. This is why NAJIT (2019) position paper points out the deficiencies of either interpreters or translators undertaking FTT tasks. Mapping the hybrid set of competencies required for FTT and mandate that such tasks be performed by those who possess both T&I credentials should be the future direction to ensure quality output.

As a relevant issue to the enquiry of who does FTT, in addition to the concerns discussed so far about the lack of specialized training nor clarity on the required competencies, another concern is that some practitioners were asked to “profile” or to “identify” speakers in forensic recordings. A practitioner may be knowledgeable in the varieties of their LOTE, relevant accents, and their associated geographical differences; however, it is a dangerous practice to rely on an unverified non-expert to supply such information without any checking mechanisms. In relation to identifying speakers in recordings, it is understandable that in the same recording, it is necessary for the practitioner to discern different speakers and assign labels such as MV1 (Male Voice 1) or FV1 (Female Voice 1). The task by itself is challenging, as voice distortions often found in intercepted phone calls are not conducive to accuracy in identifying same speakers in a talking sequence in the same recording. It is even more challenging to ask practitioners to identify whether a certain voice belongs to the same person in different recordings. Without specialist training and stringent quality procedures, practitioners' contributions will be conjectural and unreliable. Law enforcement should refrain from soliciting such input from T&I practitioners undertaking FTT tasks, as the latter may feel pressured to respond to the request, while lacking the skills and competence to do so. Further, the finding about practitioners being asked to compare handwriting in a foreign language is even more concerning, as it is positively beyond T&I practitioners' field of expertise. If law enforcement relies on the practitioner for speaker profiling, voice identification, or even handwriting comparison, when such evidence is tendered in court and doubts are raised by defense, it will not qualify as expert opinion, which is exempted from the general rule that opinion evidence is inadmissible. For example, the state of New South Wales, Australia, Section 79(1) Evidence Act (NSW) defines an expert as a person who has specialized knowledge, based on the person's training, study, or experience. In this case, the practitioner would have failed on all three accounts rendering the evidence inadmissible.

6.2. How they do it

The current study shows conclusively the need for a set of protocols to govern:

- the competencies required to undertake FTT (i.e., ideally practitioners with both T&I credentials, and specifically from LOTE into English for the former)

- the production of FTT (i.e., a two-step process to ensure audit trail, when team translation or peer checking is required)

- the provision of case briefs (i.e., whether the nature of the assignment is investigative or evidentiary, when to introduce case information and how much information)

- the format of FTT (i.e., ideally the four-column presentation as recommended in Table 2)

- transcription conventions (i.e., uniform set of transcription symbols such are in Appendix 1), level of linguistic/paralinguistic/extralinguistic details required, and threshold for confidence level (i.e. how “sure” is sure enough to commit an indistinct utterance to words assigned to them in the transcript)

- the translation approach (i.e., how to represent uncertain meanings in uncertain contexts, when and how to provide translator's notes).