Emotional competence profile in secondary school counselors: controversy or need?

- 1Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, Santiago de Compostela, Spain

- 2Universidad de Vigo, Vigo, Spain

- 3Universidad San Jorge, Zaragoza, Spain

It is out of doubt that little attention is paid to the emotional competences of secondary school counselors in research activity, as well as in their initial and ongoing training. It seems that emotional well-being is still a pending issue that may even generate some controversy, even though, today, it is defined as a clear strategy in mental health plans. Undoubtedly, we are facing a content that facilitates the contrast of points of view and social commitment as an inherent part of the democratic process. Therefore, it was decided to carry out a study, of enormous relevance, with the purpose of knowing the perceptions of secondary school counselors within the Autonomous Community of Galicia regarding emotional competences for an ideal counseling practice in complex times and moments with great challenges in the field of educational equity. Specifically, an evaluation study was carried out on the level of training received by school counselors in emotional competences and thus be able to have a diagnosis, identifying possible strengths and weaknesses. A study with a quantitative based methodology which uses the questionnaire for data collection as a main research technique. The findings obtained suggest that the quality of the teaching and learning processes in secondary schools would be substantially improved if the emotional competence profile of the counselors was considered. In particular, the interest that emotional competences arouse in counselors is confirmed, at the same time, they recognize that they can help them properly to manage the relationship processes and, the personal balance. This research, one of the first carried out in Galicia on emotional competences in secondary school counselors, provides empirical data of great interest for future training plans that are more in line with social and professional expectations, since it provides an x-ray unique, revealing, valid and real statement of the state of the matter.

Introduction

We live within a changing world, which evolves and progresses continuously, in which educational work presents rapid and constant changes in all areas. It seems that school settings, more than ever, must adapt to changing times. In this sense, teaching in Secondary Education has become an arduous task on which persists the need to reflect on the multiple secondary factors that condition it (Reoyo et al., 2017). Certainly, we are participating in turbulent moments with great challenges in educational equity, in which one of the main challenges of present society has to do with the training of educational professionals. An initial and continuous training that may allow them to satisfactorily face the demands from their nearest working space becomes highly necessary. In this context, guidance becomes a tool for the expected change in the educational framework, with the primary function of promoting an action aimed at a personal, social, and organizational transformation. It is even considered as a key element in supporting the transformations that schools must carry out to adapt to a dynamic and changing society with new requirements (Martínez Juárez et al., 2017).

To try to provide guidance under minimum quality parameters, it is necessary that guidance practices could extend to the entire educational community and throughout student’s entire life, both in the academic sphere and in the labor sphere. Therefore, the guidance activity involves the practice of a series of varied functions and demands, among which we can highlight attention to diversity, evaluation and promotion of students, health education, education in values, management of bullying situations, resolution of discipline problems, treatment of school failure, solving demotivation situations, addition of educational innovations, etc. (Hernández Rivero and Mederos Santana, 2018).

From this perspective, secondary school counselors are conceived as education professionals with the necessary pedagogical and psychological knowledge to be able to positively influence learning improvement processes and to be in a position which enables to collaborate with teachers in the comprehensive development of students from a specific role that includes the profile of counseling, consultation, trainer, informer, assistant, pedagogical director, communicator, and coordinator. Counselors are assigned a task of responsibility in the design, development, and evaluation of initiatives for the improvement of schools. They are expected to assume the role of an educational leader (Cejudo, 2016), since they are considered catalysts for change. In short, the guidance professionals seem to be obliged to adopt the role of collaborative experts who cooperate with other professionals from their own school context, with the main objective of optimizing the educational response to each student (Grañeras and Parras, 2008; Hernández-Salamanca, 2020). But to assume such an ambitious professional profile, initial training and professional development actions must be rethought (Amber and Martos, 2017).

As it can be seen, the assigned tasks are numerous, diverse, ambiguous, and poorly delimited, ranging from a more evaluative approach to a more preventive and informative one. Sometimes it is impossible to pay attention to them in their entirety, so it is crucial to establish priorities (Amor Almedina and Serrano Rodríguez, 2019; López Díez-Caballero and Manzano-Soto, 2019). Otherwise, it will give way to frustrated expectations and interventions that lack rigor. Secondary school counselors must be prepared to face the changes that are facing in their professional future as well as to overcome new goals every day. However, to achieve a correct performance of their profession, it is necessary to define their professional profile and the related number of functions. To be able to insist, at this point, on the difficulties that orienteering usually entails, whose path, to a greater or lesser extent, is strewn with pitfalls and several sources of stress, and in some cases causing risk situations such as burnout syndrome. Situations caused both by the breadth of the functions directly attributed by the educational administration and by the process of expanding the area of action itself toward curricular and organizational advisory processes, as well as the lack of knowledge of its functional profile by the teaching staff.

Sometimes, this lack of professional definition of the counselor produces a mismatch in the relational climate with teachers, since it becomes a figure that usually prescribes what is convenient to do, with the consequent tension generated in social relations. The need to participate in meetings with the teaching staff and to foster collaborative work, without being aware of it, may be confused with supervision and evaluation.

It is inevitable to know what kind of roles high school counselors value most in their practice, that is, to know to what extent a profile of counseling, of changing agent, of communicator, of consultant or resource coordinator concerns them or they regard it as something strange and forced. In this line, emotional competences can provide the opportunity to effectively face the demands that are presented every day in the exercise of guidance, since they emphasize the interaction that occurs between the person and their environment. These types of skills allow interaction with others to be developed fluently, which is the reason why they are a good indicator for success in the counseling profession. It should not be forgotten that an emotionally intelligent professional is the one capable of correctly perceiving, understanding, regulating, and applying their own emotions and those of others, minimizing the negative effect of some and enhancing the positive results of others. Undoubtedly, knowing how to handle feelings is a basic matter to be able to carry out the counseling responsibilities. It should be noted that professionals with good attention to their emotions can transfer this ability to other fields.

Emotional competences emphasize the attitudes necessary to become aware of, understand, express and appropriately regulate the emotional phenomena that need to be addressed every second of our lives (Alonso Ferres et al., 2017; Cejudo and López-Delgado, 2017; Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2017; Hernández, 2017; López-Cassá and Pérez-Escoda, 2017; Márquez Cervantes and Gaeta González, 2017; Huertas-Fernández and Romero-Rodríguez, 2019; Barrientos-Fernández et al., 2020). They constitute a stress-absorbing factor and a better coping with the multiple conflicts and negative reactions that arise in the work environment. Therefore, they play a decisive role in the optimal performance of any type of work and in the achievement of professional success, promoting personal and social well-being and fulfilling a purpose aimed at providing added value to professional functions (Álvarez-Ramírez et al., 2017; Derakhshan et al., 2023). Paradoxically, to work as a secondary education counselor, it is not necessary to carry out any prior training activity related to emotional competences, although it is recognized that they play a fundamental role in that professional field (Schoeps et al., 2019). It is striking that they are not included in the training for the profession and that the basic competences that the high school counselor must develop are not clearly identified (Cejudo, 2017).

Salovey and Mayer (1990), when they talk about emotional competences, they refer to emotional intelligence, understood as the ability to control and regulate your own feelings and others and use them as a guide for thought and action. It should be noted that the term emotional intelligence is closely related to the ability to recognize our own feelings, the feelings of others, to motivate ourselves, and to properly manage the relationships we have with others and with ourselves (Goleman, 1998; Delgado-González et al., 2023). For this reason, it is not trivial to have the skills to recognize our own feelings and those of others, to motivate oneself and persist in the face of disappointments, control impulses, delay gratification, show empathy, regulate mood, prevent difficulties from diminishing one’s ability to think, etc.

As an acquired capacity based on emotional intelligence, it can lead to an outstanding work performance, depending on the extent to which this potential has been transferred to the world of work (Goleman, 1998). The most decisive emotional competences are based not only on abilities that have to do with recognizing and understanding one’s own emotional states and their effect on other people, but also on the ability to control and redirect negative emotional impulses and states, as well as to foster empathy and socialization spaces (Pena Garrido et al., 2016). Emotional competences form the basis of a healthy and lasting professional development. However, emotional well-being is still a pending issue that can even generate some controversy, even though today it is defined as a clear strategy in mental health plans. Undoubtedly, we are facing a content that promotes the contrast of points of view and social commitment as an inherent part of the democratic process.

In this context, it seems convenient and adequate to carry out an assessment study specifically focused basically on emotional competences, under the focus of the training received. This study, pioneering in Galicia and of enormous relevance, seeks to provide a quality response to the demands arising from secondary school counseling, especially in difficult times like the ones we are witnessing. Specifically, it seeks to know the perceptions of Galician secondary school counselors about the level of training in emotional skills, as well as having a diagnosis of the level of training in emotional skills, identifying possible strengths and weaknesses.

Method

The emotional competences of secondary education counselors, as noted above, seem to constitute an element on which the effectiveness of their work lies to a certain extent. Therefore, this fact justifies an empirical approach that enables to identify possible deficiencies at this level and guide accordingly the training of these professionals. It is convenient, then, to examine the perceptions of high school counselors about their level of competence in the field of emotions to have a strategic diagnosis. In this sense, an unprecedented study was started in the Autonomous Community of Galicia to address the training of counselors in public secondary schools. An evaluation study that has a quantitative methodological design (Likert-type assessment scale).

Sample

In the quantitative phase of the study, the reference population is made up of the group of counselors who carry out their professional work in public secondary schools in Galicia (approximate number = 323). Contact was established with the entire population available to request their participation. Finally, the sample was made up of 184 guidance professionals who gave the corresponding consent to participate in the research, which represents an effective response rate of 57%, in this case more than reasonable for this type of study. A sample made up mainly of counselors, belonging to an age group between 36 and 50 years of age, with a permanent destination in the school where they work. They also have extensive experience in the educational world and in the field of guidance. 72.28% work in an IES (Secondary Education Institute) and the remaining 27.72% in a CPI (Integrated Public School). The subjects participating in the study are well acquainted with the ESO (Secondary) educational level and are used to be working with more than 250 students, in schools with more than 50 teachers. 30.43% develop their activity in urban areas and the remaining 69.5% in rural area schools. One of their most outstanding concerns is training since most of them systematically participate in continuous training and updating activities. Few have some experience running schools, although most do hold the post of head of the Guidance Department. They do not usually work cooperatively with other guidance professionals, but they are used to be working with new technologies and are trained in foreign languages. Technological tools are quite useful for them, making easier their professional and valuing the task which they perform.

Instruments

Given the complexity of the subject of research and the lack of a single, empirically proven, and universally accepted tool by the scientific community, it was decided to develop an ad hoc instrument. Specifically, a Likert-type assessment scale, made up of 92 items that allow us to investigate the training of secondary school counselors around emotional competences. The response level of the 92 items is graded in 4 points, from least to most. Two open questions were included in the instrument, as well as questions of a general nature (age, studies completed, professional category, administrative situation, years of experience in guidance, hours of training received on school guidance, years of service in the educational field, etc.). For the external and internal validity of the scale, the evaluation provided by judges was used (2 university professors specialized in educational methodology and 8 high school counselors with extensive experience in the field of guidance) and the pilot test (N = 20), thus substantially improving the final instrument. The analysis of the internal consistency of the rating scale is performed by calculating Cronbach’s ↦ coefficient, obtaining an excellent result both globally (↦Global = 0.98) and for each of the factors. The reliability coefficient was also calculated using the “Two Halves Method” (Spearman-Brown), reaching a global value of 0.97. It can be observed that the degree of internal consistency between the items of each one of the factors is considerably high, the reliability of the scale used proved to be remarkably accurate.

Procedure

After applying the research instrument online, the responses received were carefully reviewed. The data obtained were numerically coded through a coding table where the values given to each response in the different variables were recorded. To detect possible inconsistencies, both frequency and contingency tables were used, which in this case made it possible to correct the anomalies detected. To estimate the quality of the final data matrix, a representative sample of questionnaires (n = 37) was selected, 20% of the total number of questionnaires answered for its punctual verification. The percentage of error found was less than 0.05%, assuming the quality of the data as high and proceeding to its final analysis.

For the analysis of quantitative data, with the help of the statistical package SPSS.20 and the AMOS.20 program, strategies such as:

• “Uni” and “bivariate” tabulation, including percentages in the case of categorical variables and descriptive statistics (medias and standard deviations) for quantitative variables.

• Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) by the Principal Components method, for the identification of competence factors or “macro competences.”

Results

To examine the internal structure of the scale and identify the underlying factors, using the Principal Components Method, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was carried out. As input data, the direct scores referring to training in 88 of the 92 initial items were used, setting aside 4 of them, given the scant relevance and applicability received by the study subjects. The KMO index was 0.935 and the Bartlett’s Sphericity Test (13795.49) was statistically significant (p < 0.001), indicating that the input matrix could be estimated as suitable for factorization. The resulting analysis offered a total of 14 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, which jointly explained 70.04% of the Variance of the data. Later, a Varimax rotation was applied to allow the independence of the factors and thus achieve a better characterization.

After the first item screening, a second EFA was carried out, leaving the new scale made up of 60 items, once again using the Principal Components method and a Varimax rotation. The KMO index was 0.942 and the Bartlett’s Sphericity Test was 8641.37 (p < 0.001). The resulting analysis provided a total of 10 factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, which jointly explained 68.62% of the Variance of the data, almost 1% less than that obtained with 88 items. The factorial structure obtained is more consistent.

To check the internal consistency of the scale, Cronbach’s ↦ coefficient was calculated, obtaining an excellent result both globally (↦Global = 0.98) and for each of the factors separately, considering that some factors consist of only 4 items.

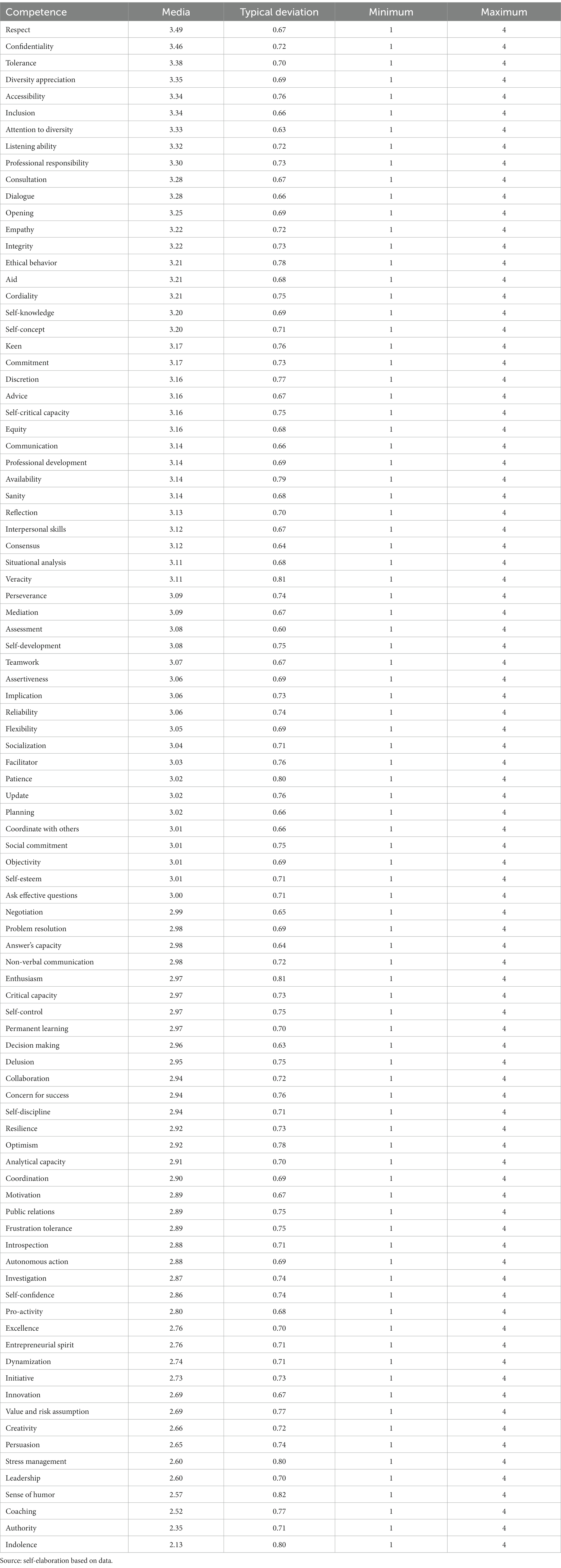

Hereinafter, the results obtained in the study are described after applying the descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum) to the items that make up the assessment scale to assess the level of perception that the guidance professionals themselves have about their training in emotional competences (see Table 1).

As it can be seen, the data obtained is revealing. In general terms, it is observed that the 12 competences with a high degree of training received by guidance professionals, on a scale from 1 to 4, are: “Respect” (3.49), “Confidentiality” (3.46), “Tolerance” (3.38), “Appreciation of diversity” (3.35), “Accessibility” (3.34), “Inclusion” (3.34), “Attention to diversity” (3.33), “Ability to listen” (3.32), “Responsibility professional” (3.30), “Consultation” (3.28), “Dialogue” (3.28), and “Opening” (3.25).

On the other hand, among the 12 competences with a lower level of perception are: “Indolence” (2.13), “Authority” (2.35), “Coaching” (2.52), “Sense of humor” (2.57), “Leadership” (2.60), “Stress management” (2.60), “Persuasion” (2.65), “Creativity” (2.66), “Courage and risk taking” (2.69), “Innovation” (2.69), “Initiative” (2.73), and “Dynamization” (2.74).

Likewise, the results of the study reveal that the secondary school counselors surveyed have a high level of training in the “Confidentiality” competence, the second-best valued option. It can also be seen that the research subjects feel specially trained in competences attached to capacities related to social sensitivity, since competences such as “Tolerance,” “Appreciation of diversity,” “Accessibility,” “Inclusion” and “Attention to diversity,” occupy the third, fourth, fifth, sixth and seventh place, respectively.

The competence “Listening ability” (3.32) appears located in the eighth place, which indicates that the subjects participating in the study believe that they are well trained in a vital aspect for the knowledge of the oriented. The “Empathy” competence ranks 13th. In the group of competences in which Galician counselors perceive themselves to be specially trained, the “Advice” competence stands out (obtaining position 23) and the “Communication” competence, ranking in this case in position 26.

The “Teamwork” competence, as can be seen, appears located in position 39, which means a low training rate. Something similar happens with the “Assertiveness” competence (located in position 40) and the “Coordinate with others” competence, which is in 49th place. A striking fact is the position obtained by the “Self-control” competence, located in position 60. The “Collaboration” competence (located in position 63) and the “Motivation” competence, in position 78, reflect a significant lack of training. It is also necessary to underline the behavior of the “Coordination” competence, with a position of 70.

The “Proactivity,” “Entrepreneurship” and “Initiative” skills, preferred skills for starting and leading genuine projects, occupy positions 77, 79, and 81, respectively. The “Innovation” competence receives a low rating, occupying position 82. The “Stress Management” competence appears as the fifth competence with the lowest score received on the evaluation scale, occupying position 87. The “Leadership” competence is located at position 88. The competence “Sense of humor” occupies position 89. The competence “Coaching” is in position 90. This reflects a low training of the counselor in this type of competence.

The secondary education counselors surveyed, on the other hand, consider themselves poorly trained in “Indolence.” The extracted data reveal this if we consider that this competence is ranked 92. This implies that emotions such as apathy, neglect, laziness, lack of response or abandonment are not part of their work culture.

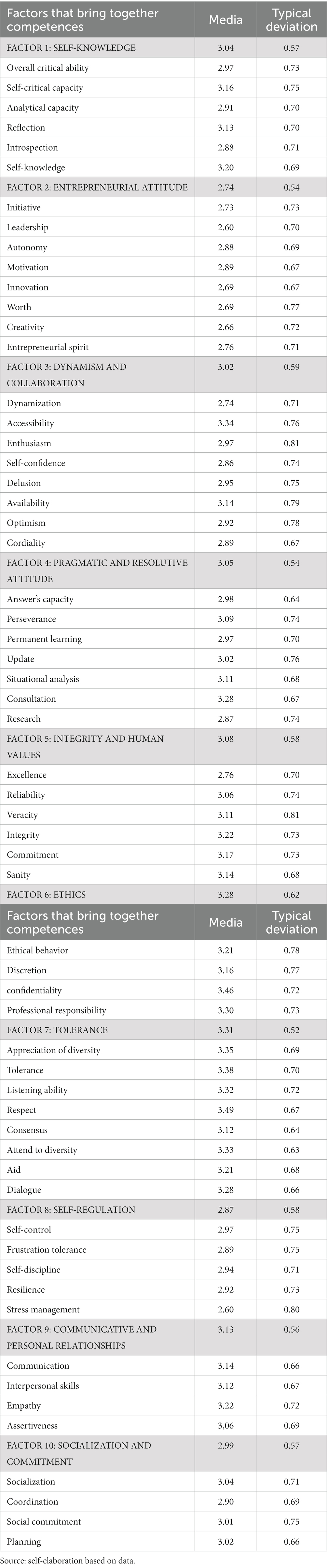

Below are the data obtained after applying an Exploratory Factor Analysis, EFA, to the items, thus bringing together the competences in 10 factors based on the saturations produced (saturations greater than 0.35). In Table 2, we present the corresponding results.

Planning

The data resulting from the 10 factors in which the items were agglutinated, after applying the Exploratory Factor Analysis, show a disparate behavior, appearing significant differences between them. Thus, for example, the factor “Tolerance” (3.31) yields higher results. This factor integrates competences such as: “Appreciation of diversity,” “Tolerance,” “Ability to listen,” “Respect,” “Consensus,” “Attention to diversity,” “Help” and “Dialogue.” Followed by the “Ethics” factor (3.28), configured by the following competences: “Ethical behavior,” “Discretion,” “Confidentiality” and “Professional responsibility.” And, of the factor “Communication and personal relationships” (3.13), which includes the competences “Communication,” “Interpersonal skills,” “Empathy” and “Assertiveness.”

And at the other extreme, with a low formative appreciation, is the factor “Entrepreneurial attitude” (2.74), which is made up of the competences: “Initiative,” “Leadership,” “Autonomy,” “Motivation,” “Innovation,” “Courage,” “Creativity” and “Entrepreneurship.” Followed by the “Self-regulation” factor (2.87) composed of the “Self-control,” “Frustration tolerance,” “Self-discipline,” “Resilience” and “Stress management” competences. And, “Socialization and commitment” (2.99), made up of the competences “Socialization,” “Coordination,” “Social commitment” and “Planning.”

Discussion

Emotional competences constitute a powerful tool that can greatly facilitate the work of guidance in secondary education, since they are decisive in personal interactions (Bisquerra Alzina and Lopez Cassa, 2021; Rodríguez-Pérez et al., 2021) and are essential to manage a work environment often characterized by conflicts, stress, and complex situations with the educational community (Rodríguez Álvarez et al., 2017; Prieto, 2018). It is verified, once again, that socio-emotional competences are considered a valuable instrument that offers guarantees for job success, since they help to quell job tension by facilitating work when the context is hostile and helping to manage relationship processes. and personal balance (Chianese and Prats Fernández, 2021; Martínez-Saura et al., 2021). Ultimately, they promote social commitment and democratic participation from an inclusive framework.

The professional exercise of guidance in secondary school presents certain vicissitudes that foster the need for a solid training load linked to the management of one’s own emotions and those of others (Prieto, 2018). Some researchers (García-Domingo, 2021; García-Vila et al., 2022) regret the explicit exclusion of emotional competences in initial training programs, since they are essential for the successful development of any activity related to the human being. High school guidance professionals appreciate that, beyond knowledge in specific areas, it is essential to have robust attitudinal training to promote good professional work in the field of educational guidance. Despite the advances, we present a deterioration in the ability to manage emotions.

In the current context, it is increasingly appreciated that job performance cannot be predicted through school grades. Academic intelligence is not enough to achieve professional success. Therefore, as Martínez-Pérez (2023) states, emotional competences must be at the same level of training as other competences (conceptual and procedural). However, even though they are considered relevant for guidance practice, they represent a weak point in the training of secondary school guidance counselors, both initial and permanent. The exercise of the guidance profession requires some skills in which its professionals want to feel prepared, safe, and strong. The reality, unfortunately, does not seem to go in that direction. The secondary school counselors surveyed attribute severe deficiencies in the formation of emotional competences, as confirmed in the evaluation study carried out. For this reason, it is appropriate that the Galician Educational Administration assume the responsibility of facing this challenge with due coherence and energy, especially in times of maximum vulnerability such as those we are witnessing. It is urgent to establish a serious, rigorous, coherent, and well-structured training plan, which allows the development of training actions of this nature. A training plan that integrates the study of emotions in a structured way (García et al., 2018).

The findings of this study show that the three competences on which the training load of secondary school guidance professionals is focused on are: “Respect,” “Confidentiality,” and “Tolerance.” Consequently, they constitute the emotional pillars of the counselors consulted. High school guidance professionals seem to have a high level of training to guarantee the autonomy of those guided, their freedom in decision-making and to make a careful and responsible use of the testimonials obtained, given that the “Respect” competence obtains the highest score. An important issue in the guidance activity, as pointed out by Grañeras and Parras (2008). The fact that the “Confidentiality” competence obtains a good assessment shows the importance of the ethical code in the professionalization of the counselor.

The “Empathy” competence, which trains to know what others feel and understand the difficulties of a user (Goleman, 1995), ranks 13th. We are talking about a fundamental competence in building the relationship with the educational community and, therefore, involved in a wide spectrum of activities that secondary school counselors carry out. The secondary school counselors participating in the study perceive themselves to be specially trained in the “Counseling” competence, obtaining 23rd place. This is a key task in the work of guidance professionals, being among the competences assigned to the Departments of Guidance in Secondary Schools from the Galician Educational Administration.

At the opposite extreme, the competences that present a high level of lack from the perspective of the surveyed guidance professionals themselves are: “Indolence,” “Authority” and “Coaching.” Therefore, they make up the block of skills with a low training profile. In relation to the “Coaching” competence, with a position of 90, what is revealed is a lack of knowledge about this field of knowledge. It is still contradictory since the counselor gives counseling with a specific objective daily. The development of “Coaching” is a great challenge for the profession itself (Bisquerra, 2008), so this type of competence should be addressed in initial and ongoing training.

The “Teamwork” competence appears located in position 39, which means a low rate of training. It is striking because teamwork is necessary in the educational world. If we add to this data that the competence “Coordinate with others” is ranked 49th, clear indications are obtained that the predominant culture in secondary schools seems to be characterized by isolation (Martínez Garrido et al., 2010). Regarding the “Collaboration” competence, located in position 63, a significant training gap is reflected. This result seems to indicate that this competence is not always promoted in the initial training of secondary school counselors, despite being essential to be able to develop collaborative processes in schools. Therefore, it is necessary to promote the “Collaboration” competence from the educational administration, to achieve the necessary training and be able to break with the role of expert of the counselor. It is urgent here to favor a collaborative position with each one of the members of the educational community, from a preventive and systemic approach. Also highlight the behavior of the “Coordination” competence, with a position of 70. It shows, in some way, a lack of training, despite appearing among the functions of secondary school counselors.

The factors whose training is considered most suitable are: “Tolerance,” “Ethics” and “Communication and personal relationships.” In this sense, the results obtained reveal optimal training in the “Communication” competence, ranking in 26th place in this case. It is a competence perceived as essential by most experienced counselors (Grañeras and Parras, 2008). The result of the “Assertiveness” competence, located in position 40, is striking. A competence that allows promoting equality between human relations, an aspect present in the professional practice of the counselor/high school and highlighted by various authors (Goleman, 1995; Repetto and Pena, 2010). We are facing a competence that allows the counselor to be able to act in defense of their interests, defend themselves without unjustified anxiety, sincerely express their feelings and carry out their rights (Repetto and Pena, 2010). Consequently, it becomes a key competence for a good secondary school guidance professional.

The factors in which the level of training is perceived to be weaker are: “Entrepreneurial attitude,” “Self-regulation” and “Socialization and commitment.” The training deficit found in the “Self-regulation” factor, which integrates skills such as “Self-control,” “Frustration tolerance,” “Self-discipline,” “Resilience,” and “Stress management,” is surprising, considering that we are facing a determining factor when it comes to managing emotions. It should be remembered that this factor makes it possible to neutralize situations that generate negative emotions and that represent a significant waste of energy. Undoubtedly, it makes it possible to maintain the helm of obligations, despite the turbulence and even “tsunamis” in which school counselors are often involved. The “Stress Management” competence can help to design actions and strategies that allow the development of concrete prevention and intervention plans to avoid stress, emotional exhaustion, and depersonalization. The training gaps detected in the “Stress Management” skill, the fifth skill with the lowest score received on the assessment scale, highlights the need for its inclusion in training plans. It cannot be ignored that we are facing a core competence in the counseling profession, since among the sources of stress perceived by secondary school counselors are: the breadth and diversity of tasks, the low awareness of teachers to assume a response to the specific needs for educational support, the difficulty in assuming the functions included in the regulations, the precarious ongoing training received, the problems in carrying out effective and efficient coordination between professionals, etc. It seems that the most emotionally competent high school counselors have the necessary resources to better cope with stressful situations and adequately manage the negative emotional responses that frequently appear in interactions with co-workers, family, and students. The position obtained by the “Self-control” competence, located in position 60, is amazing. It is not a high and expected score, as it is a competence that allows you to manage impulsive feelings, seeking balance at the most critical moments. At the same time, this competence makes it possible to think clearly despite the pressures received (Goleman, 1998). In short, we are facing a competence related to how to regulate one’s own emotions and those of others, which moderates negative emotions, intensifying positive ones and minimizing negative ones. Similarly, the “Motivation” competence is shown (position 78). The competence par excellence, among the counselor’s socioemotional competences (Repetto and Pena, 2010). Although, it is possible that this result is mediated by the culture of isolation, sometimes predominant in schools or may reflect the attitude of demotivation and lack of commitment in many teachers (Martínez Garrido et al., 2010).

The “Innovation” competence receives a low rating, occupying position 82. This seems to indicate that the secondary school counselor has not just received training in this field, as others have already confirmed (Velaz-de-Medrano et al., 2013). The “Leadership” competence is ranked 88th. It should be part of the competence training of all counselors, considering that a decision-making style is necessary to assume, promote and develop a new professional culture in the exercise orientation as proposed by Medina and Gómez (2014). And, even, in some cases, the role of leader must be signified by personal and professional pre-eminence over a group, capable of influencing the decisions and positions adopted (Amber and Martos, 2017). The score received in a competence such as “Sense of Humor” is notable, with a position of 89. On some occasions, this competence helps to cope with certain situations and guarantees personal well-being. It is increasingly considered in the professional field, although it is true that a sense of humor can be defined as a very subjective quality and is not always understood in the same way. In fact, sometimes it can even cause misunderstandings.

Conclusions and implications

The study which was carried out, was of great importance and interest for the entire educational community (teachers, students, tutors, families, etc.) and particularly for school counselors. Therefore, the results of the study will be of great help, even though the field of emotions and its research can be very controversial.

In any case, it is necessary to outline the nature of emotional processes in educational contexts, promoting the generation of valuable measurement instruments with adequate psychometric properties and the implementation of intervention programs that promote emotional competences. Perhaps one of the greatest challenges is to provide evidence regarding the benefits of emotional education, appealing to solid and cutting-edge research with contributions from new methodological frameworks.

This study is not an end point. Rather, it opens new horizons to continue investigating this complex reality. The needs for further study, given the scarcity of studies focused exclusively on the topic addressed, leading us to continue with line of work from a qualitative perspective, using discussion groups and/or in-depth interviews as data collection techniques.

The main limitation of this study is that its results cannot be generalized to the entire school context of the Spanish State. In this sense, it is convenient to expand the sample to other Autonomous Regions and even extend it to other educational levels in order to obtain greater empirical evidence, exploring possible differences.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

JV: Investigation, Writing – original draft. MF: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MM: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Alonso Ferres, M., Berrocal de Luna, E., and Jiménez Sánchez, M. (2017). Estudio sobre la inteligencia emocional y los factores contextuales en estudiantes de cuarto de educación primaria de la provincia de Granada. Revista de Investigación Educativa 36, 141–158. doi: 10.6018/rie.36.1.281441

Álvarez-Ramírez, M. R., Pena Garrido, M., and Losada Vicente, L. (2017). Misión posible: mejorar el bienestar de los orientadores a través de su inteligencia emocional. REOP 28, 19–32. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.28.num.1.2017.19356

Amber, D., and Martos, M. A. (2017). Ámbitos y funciones de los orientadores para la mejora educativa en secundaria en contextos restantes. Una mirada cruzada entre orientadores y directivos. PRO 21, 419–437. doi: 10.30827/profesorado.v21i4.10063

Amor Almedina, M. I., and Serrano Rodríguez, R. (2019). Las competencias profesionales del orientador escolar: el rol que representa desde la visión del alumnado. Revista de Investigación Educativa 38, 71–88. doi: 10.6018/rie.321041

Barrientos-Fernández, A., Pericacho-Gómez, F. J., and Sánchez-Cabrero, R. (2020). Competencias sociales y emocionales del profesorado de Educación Infantil y su relación con la gestión del clima de clase. Estudios sobre Educación 38, 59–78. doi: 10.15581/004.38.59-78

Bisquerra, R. (2008). Orientación psicopedagógica: áreas y funciones. E. J. Santos (Comps). Funciones del Departamento de Orientación (pp. 11–37). MEC.

Bisquerra Alzina, R., and Lopez Cassa, E. (2021). La evaluación en la educación emocional: Instrumentos y recursos. Aula Abierta 50, 757–766. doi: 10.17811/rifie.50.4.2021.757-766

Cejudo, J. (2016). Relación entre Inteligencia Emocional y salud mental en Orientadores Educativos. Electron. J. Res. Educ. Psychol. 14, 131–154. doi: 10.14204/ejrep

Cejudo, J. (2017). Competencias profesionales y competencias emocionales en orientadores escolares. Profesorado Revista de Currículum y Formación del Profesorado 21, 349–370.

Cejudo, J., and López-Delgado, M. L. (2017). Importancia de la inteligencia emocional en la práctica docente: un estudio con maestros. Psicología Educativa 23, 29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pse.2016.11.001

Chianese, C., and Prats Fernández, M. Á. (2021). Desarrollo de las competencias emocionales del profesorado de secundaria mediante una intervención integral en coaching. REOP 32, 110–131. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.32.num.2.2021.31282

Delgado-González, Y., Chinea-Gómez, L., and Ruíz-Pérez, O. (2023). La atención a la diversidad para la educación emocional desde la función orientadora del docente. RETOS XXI 7. doi: 10.30827/retosxxi.7.2023.25347

Derakhshan, A., Wang, Y., Wang, Y., and Ortega-Mart, J. L. (2023). Towards innovative research approaches to investigating the role of emotional variables in promoting language teachers’ and learners’ mental health. Int. J. Ment. Health Promot. 25, 823–832. doi: 10.32604/ijmhp.2023.029877

Fernández-Berrocal, P., Cabello, R., and Gutiérrez-Cobo, M. J. (2017). Avances en la investigación sobre competencias emocionales en educación. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 88, 15–26.

García, M., Hurtado, P. A., Quintero, D. M., Rivera, D. A., and Ureña, Y. A. (2018). La gestión de las emociones, una necesidad en el contexto educativo y en la formación profesional. Revista ESPACIOS 49, 8–19. Available at: http://www.revistaespacios.com/a18v39n49/a18v39n149p08.pdf

García-Domingo, B. (2021). Competencia emocional en maestros de educación infantil y primaria: fuentes de variabilidad y sugerencias de mejora. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 24, 1–15. doi: 10.6018/reifop.450111

García-Vila, E., Sepúlveda-Ruiz, M. P., and Mayorga-Fernández, M. J. (2022). Las competencias emocionales del alumnado de los Grados de Maestro/a en Educación Infantil y Primaria: una dimensión esencial en la formación inicial docente. Revista Complutense de Educación 33, 119–130. doi: 10.5209/rced.73819

Grañeras, M., and Parras, A. (2008). Orientación educativa: fundamentos teóricos, modelos institucionales y nuevas perspectivas CIDE.

Hernández, V. (2017). Las competencias emocionales del docente y su desempeño profesional. Alternativas en Psicología 37, 79–92. Available at: https://www.alternativas.me/26-numero-37-febrero-julio-2017/147-las-competencias-emocionales-del-docente-y-su-desempeno-profesional

Hernández Rivero, V., and Mederos Santana, Y. (2018). Papel del orientador/a educativo como asesor/a: funciones y estrategias de apoyo. REOP 29:40. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.29.num.1.2018.23293

Hernández-Salamanca, O. G. (2020). Percepción social de la orientación escolar en orientadores de Bogotá. Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía 31, 131–144. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.31.num.1.2020.27294

Huertas-Fernández, J. M., and Romero-Rodríguez, S. (2019). La autonomía emocional en el profesorado de secundaria. Análisis en el Marco de un proceso de coaching personal//emotional autonomy in secondary teachers. Analysis in the framework of a life coaching process. REOP 30, 120–139. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.30.num.3.2019.26276

López-Cassà, E., Pérez-Escoda, N., and Alegre, A. (2017). Competencial emocional, satisfacción en contextos específicos y satisfacción con la vida en la adolescencia. Revista de Investigación Educativa 36, 57–73. doi: 10.6018/rie.36.1.273131

López Díez-Caballero, M. E., and Manzano-Soto, N. (2019). Valoración del nuevo modelo de orientación implementado en la comunidad autónoma de Cantabria por parte de los orientadores educativos//Evaluation of the new counseling model carried out in Cantabria by guidance teachers. REOP 30, 108–127. doi: 10.5944/reop.vol.30.num.2.2019.25341

Márquez Cervantes, M. C., and Gaeta González, M. L. (2017). Desarrollo de competencias emocionales en pre-adolescentes: el papel de padres y docentes. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado 20, 221–235. doi: 10.6018/reifop/20.2.232941

Martínez Garrido, C. A., Krichesky, G., and García Barrera, A. (2010). El orientador escolar como agente interno de cambio. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación 54, 107–122. doi: 10.35362/rie540544

Martínez Juárez, M., González Morga, N., and Pérez Cusó, J. (2017). Aproximación al perfil formativo del orientador profesional en la blogosfera. Revista de Investigación Educativa 36, 39–56. doi: 10.6018/rie.36.1.306401

Martínez-Pérez, L. (2023). Pedagogía con corazón: el aprendizaje socioemocional con el modelo HEART in Mind©. Revista Internacional de Educación Emocional y Bienestar 3, 13–34. doi: 10.48102/rieeb.2023.3.2.53

Martínez-Saura, H. F., Sánchez-López, M. C., and Pérez-González, J. C. (2021). Competencia emocional en docentes de Infantil y Primaria y estudiantes universitarios de los Grados de Educación Infantil y Primaria. Estudios sobre Educación 42, 9–33. doi: 10.15581/004.42.001

Medina, A., and Gómez, R. M. (2014). El liderazgo pedagógico: competencias necesarias para desarrollar un programa de mejora en un centro de educación secundaria. Revista perspectiva educacional formación de profesores. doi: 10.4151/07189729

Pena Garrido, M., Extremera Pacheco, N., and Rey Peña, L. (2016). Las competencias emocionales: material escolar indispensable en la mochila de la vida. PYM 6–10. doi: 10.14422/pym.i368.y2016.001

Prieto, M. (2018). La psicologización de la educación: implicaciones pedagógicas de la inteligencia emocional y la psicología positiva. Educación XXI 21, 303–320. doi: 10.5944/educXX1.20200

Reoyo, N., Carbonero, M. A., and Martín, L. J. (2017). Características de eficacia docente desde las perspectivas del profesorado y futuro profesorado de secundaria. Revista de Educación 376, 62–86. doi: 10.4438/1988-592X-RE-2017-376-344

Repetto, E., and Pena, M. (2010). Las competencias socioemocionales como factor de calidad de la educación. Revista Iberoamericana sobre calidad, eficacia y cambio en educación. REICE 8, 82–99. doi: 10.15366/reice2010.8.5.005

Rodríguez Álvarez, P., Ocampo Gómez, C. I., and Sarmiento Campos, J. A. (2017). Valoración de la orientación profesional en la enseñanza secundaria postobligatoria. Revista de Investigación Educativa 36, 75–91. doi: 10.6018/rie.36.1.285881

Rodríguez-Pérez, S., Sala-Roca, J., Doval, E., and Urrea-Monclús, A. (2021). Diseño y validación del Test Situacional Desarrollo de Competencias Socioemocionales de Jóvenes (DCSE-J). RELIEVE 27, 1–17. doi: 10.30827/relieve.v27i2.22431

Salovey, P., and Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Baywood Publishing Co. 9, 185–211. doi: 10.2190/DUGG-P24E-52WK-6CDG

Schoeps, K., Tamarit, A., González, R., and Montoya-Castilla, I. (2019). Competencias emocionales y autoestima en la adolescencia: impacto sobre el ajuste psicológico. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes 6, 51–56. doi: 10.21134/rpcna.2019.06.1.7

Keywords: guidance, training, emotional competence, secondary education, well-being

Citation: Fernández Tilve MD, Malvar Méndez ML and Varela Tembra JJ (2024) Emotional competence profile in secondary school counselors: controversy or need? Front. Educ. 8:1277638. doi: 10.3389/feduc.2023.1277638

Edited by:

Delfín Ortega-Sánchez, University of Burgos, SpainReviewed by:

José Luis Ortega-Martín, University of Granada, SpainGabriel Sánchez-Sánchez, University of Murcia, Spain

Copyright © 2024 Fernández Tilve, Malvar Méndez and Varela Tembra. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: María Dolores Fernández Tilve, mdolores.fernandez.tilve@usc.es

María Dolores Fernández Tilve1*

María Dolores Fernández Tilve1*  Juan José Varela Tembra

Juan José Varela Tembra