- 1Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Chungnam National University Hospital and Chungnam National University College of Medicine, Daejeon, South Korea

- 2Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Seoul National University Bundang Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seongnam, South Korea

- 3Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Pusan National University School of Medicine, Pusan National University Yangsan Hospital, Pusan, South Korea

- 4Clinical Trials Center, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, South Korea

- 5Department of Public Health and Medical Services, Chungnam National University Hospital, Daejeon, South Korea

Objective: To investigate the available evidence on early supported discharge (ESD) and transitional care (TC) delivery service in patients with cerebrovascular disease.

Methods: A systematic literature search was conducted to collect all available evidence on the use of ESD and TC services. We included cluster-randomized pragmatic trials or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that recruited patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack to receive either conventional care or any care service intervention that included rehabilitation or support provided by professional medical personnel with the aim of accelerating and supporting home discharge. Relevant data were electronically searched through international databases (Cochrane Library, EMBASE, and PubMed) and incorporated into a summary grid to investigate research outcomes and provide a narrative synthesis. Furthermore, we compared the outcomes in terms of length of hospital stay, patient and caregiver outcomes, and mortality through meta-analysis.

Results: We identified and included a total of 20 publications of various original randomized studies. There were 18 studies conducted in western countries and 2 in eastern countries. The meta-analysis revealed a tendency that ESD or TC could decrease the length of hospital stay more than the usual care [standardized mean difference (SMD) −0.13; 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.31 to 0.04 days; P = 0.14]. Moreover, there was a tendency that ESD resulted in better activities of daily living (ADL) than usual care (SMD 0.29; 95% CI −0.04 to 0.61; P = 0.08). Patient outcome based on modified Rankin scale (mRS) score (SMD −0.11; 95% CI −0.38 to 0.17; P = 0.45] and mortality (odds ratio 0.80; 95% CI 0.56–1.17; P = 0.25) did not reveal any significant difference. The Caregiver Strain Index revealed no difference.

Conclusion: We did not find a large effect size for the use of TC and ESD. When implementing the TC and ESD model from western to Asian countries, services should be prepared and implemented in accordance with national medical rehabilitation pathways for cerebrovascular disease.

Introduction

In national stroke guidelines of the USA (1), Canada (2), and Scotland (3), early supported discharge (ESD) is recommended as a rehabilitation strategy for post-acute care. In the UK, ESD is part of the stroke care system, and the target group, purpose, scope, and method of ESD are specified in the manuals (4, 5). Langhorne et al. reported that an ESD service comprising a multi-disciplinary team reduced long-term functional dependence and readmission in stroke patients and significantly shortened the length of hospital stay compared with the previous service (6). In particular, the total average length of hospital stay was reduced to 6 days, and the incidence of negative outcomes, such as death or readmission, was reduced by ~5%. No significant differences were noted in the results reported in previous studies; however, the cost of the ESD program was 15–23% lower than that of conventional treatment (6).

In the USA, transitional care (TC) services are provided for various acute diseases (7). TC in the USA must satisfy the following three criteria: contact with the patient within 2 days of discharge, face-to-face follow-up interview/evaluation within 7 or 14 days of discharge depending on the severity of the disease, and non-face-to-face care service according to the patient's needs.

However, in a recent survey on TC including 40 hospitals in North Carolina, only 31.7% of the hospitals satisfied the above-mentioned three criteria of TC (8). Duncan et al. analyzed the effects of nationwide systematic TC in the USA; however, the effects were uncertain (9). The Cochrane review categorized several stages of ESD from full service with mobile rehab team to some minimal counseling before discharge (6). We thought that both ESD and TC could be in the same category of post-acute care (PAC) of stroke with a wide range of spectrum.

In Korea, as the number of cerebrovascular disease patients is increasing due to population aging, efforts are being made to provide standardized acute treatments by developing guidelines for stroke treatment, implementing quality evaluation control by the Health Insurance Review Assessment Service, and opening 14 regional cardio-cerebrovascular centers nationwide. As a result, the mortality rate of acute stroke is decreasing. However, unlike cardiovascular disease, stroke causes neurological disorder. Therefore, the number of stroke survivors who have disabilities after initial treatment and require care in hospitals, facilities, and communities has increased. Accordingly, the medical cost for rehabilitation and management after acute stroke treatment is also increasing. Therefore, there is a need for a continuous management model based on disability and patient characteristics after acute stroke treatment. Studies must focus on developing and standardizing continuous TC and a management model according to the triage for post-stroke care and analyze the effects and hindrance factors of the model in clinical settings.

Therefore, this aimed to investigate the effects of ESD and TC programs on mortality, readmission rate, length of hospital stay, and function through a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of existing and most recent data.

Materials and Methods

Data Searches and Sources

A literature search was conducted using databases, including PubMed, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Library. For an extensive literature search, only the participants (P) and intervention (I) were considered, and searches were conducted using keywords, such as “stroke,” “transient ischemic attack (TIA),” “early supported discharge,” “transitional care,” and “rehabilitation.” The databases and search formulas used in each database are presented in Table 1.

Study Selection

The key question was selected according to a discussion about previous studies and expert opinion. The key question was “Can transitional care, including early supported discharge (ESD), have an impact on functional outcomes, readmission, mortality, and length of hospital stay after acute cerebrovascular accident?” Table 2 describes the detailed strategies for study inclusion, including population, intervention/comparator, outcomes, time, setting, and design (PICOTS-SD). We included randomized pragmatic trials (RPTs) or randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that recruited patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack to receive either conventional care or any care service intervention, wherein rehabilitation or support was provided by professional medical personnel with the aim of accelerating and supporting home discharge. The RPT provides a real-world assessment of a new care model vs. the usual care. It did not include a control group but a usual care group was examined (9). The outcome parameters for effectiveness included functional status, readmission rate, mortality, and caregiver burden. We selected studies published after 1997, given that there were significant changes in the PAC of stroke patients, such as ESD implementation in London and UK.

Literature Screening Strategy

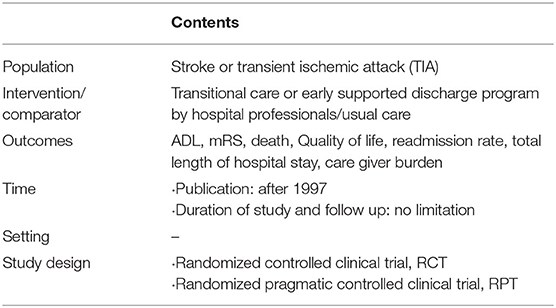

All the articles searched on each database were merged, and articles that were searched multiple times were removed. Thereafter, the title and abstract of the studies were reviewed to exclude irrelevant studies. If no decision could be made based on the title and abstract, the full text was systematically reviewed and analyzed. The literature review and analysis were conducted by the main researcher and another researcher with experience as an occupational therapist. Data were extracted by choosing necessary items from the list of available data in the selected articles. Two or more researchers independently extracted the data, and disagreements were settled through discussion. The main data that were extracted included study characteristics (study design, country, period, and patient inclusion criteria), patient characteristics (number of participants, disease classification, interventions for intervention and control groups, and location), and clinical outcomes. Each variable is described in the Supplementary Table 1. TC interventions were divided into two types: type I for interventions performed by medical staff, including doctors and nurses, excluding visiting rehabilitation; and type II for interventions that included visiting rehabilitation. This was a modified version of the method used in the Cochrane review (6). The key search terms related to “early supported discharge for stroke patients” were used to search articles in international literature search databases such as PubMed, Embase, and the Cochrane Library. The total number of searched articles was 15,090, excluding those that were searched multiple times. The search formulas for each database are shown in the Table 1. In the 1st literature selection process, the title of the studies was reviewed to assess relevance. In the 2nd selection process, the abstract was reviewed to assess relevance to key questions, and a total of 44 studies were selected. Lastly, the main text of articles selected in the 2nd selection process was reviewed according to the selection and exclusion criteria. Finally, 20 articles (articles 1–20) were selected for systematic literature review. In the meta-analysis process, the subgroup study (n = 1) of other study and long-term (>5 years) follow-up studies (n = 2) were excluded to reduce bias. Figure 1 illustrates a flowchart for selection of the articles included in this systematic literature review. Articles 5, 12, and 19 were excluded in the quantitative analysis process.

Quality Assessment of the Literature

The risk of bias (RoB) of the studies was assessed using the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool. Two researchers independently assessed the RoB of the selected studies, and disagreements were settled through discussion to reach a consensus. The detailed guidelines are described in Supplementary Table 2. RoB. If there was insufficient information about the relevant items, the RoB was evaluated as “uncertain (yellow).” If the RoB was small, it was evaluated as “low (green).” We measured RoB for only 17 RCTs excluding one RPT (article 9).

Statistical Analysis

Data were extracted in accordance with several categories, including study characteristics (design, country, duration, inclusion criteria), patient characteristics (numbers, disease categories, type of intervention, age, the composition of case and control group, place, duration of intervention, and frequency), and clinical outcomes. If a quantitative measurement was possible, we conducted a meta-analysis and confirmed heterogeneity, or we described the data qualitatively. We used the outcome value at the longest follow-up of each study. Dichotomous outcomes are presented as relative risks with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Variance and heterogeneity among the included studies were explored using forest plots and I2 statistics, respectively. Data from each study were pooled using a fixed-effects meta-analysis model for the analysis with I2 > 75% as well as by the random-effects model. If statistical heterogeneity was identified, meta-regression was conducted to explore the covariance, which affects the random effects, and to confirm the reason for heterogeneity. All statistical analyses were performed using the Review Manager 5.3 software (RevMan 2014, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark).

Results

Systematic Review

General Characteristics and Various Outcomes of Included Studies

This literature review finally examined 20 articles, of which 19 were RCTs and 1 was an RPT. Regarding international location, 85% of the studies were conducted in Europe [Norway (10–15): 6, Denmark (16–20): 5, Netherlands (21): 1, Sweden (22, 23): 2, UK (24, 25): 2, Portugal (26): 1], 10% were conducted in Asia [China (27): 1, Hong Kong (28): 1], and 5% were conducted in North America [USA (9): 1]. For the intervention types, seven studies provided type I intervention, whereas 13 studies provided type II intervention. The greatest number of studies (38%) followed up the participants for more than 12 months, whereas 33% and 28% of the studies followed up the participants for 3–6 months and <3 months, respectively. The publication year ranged from 1997 to June 2020. The greatest number of studies was published in 2004 (four studies). Two studies were published in each of 2002, 2019, and 2020, whereas one study was published each in 1997, 2000, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2009, 2011, 2014, 2015, 2016, and 2017. The list of the selected studies and the characteristics of each study are shown in Supplementary Table 3. The study design, study country, and publication year were described in a reverse order. The outcomes (measured values) of each study are summarized in Supplementary Table 4.

Meta-Analysis

Patient Outcomes

Length of Hospital Stay

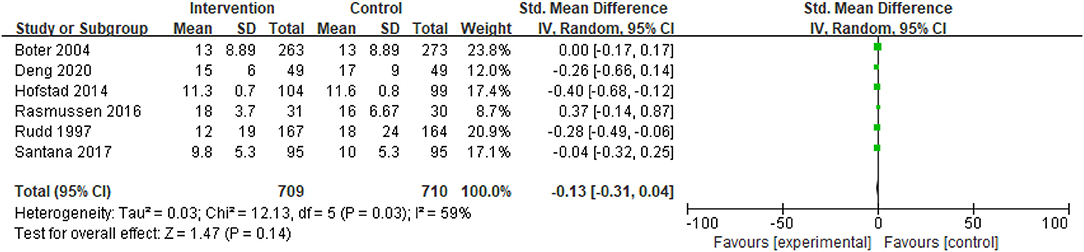

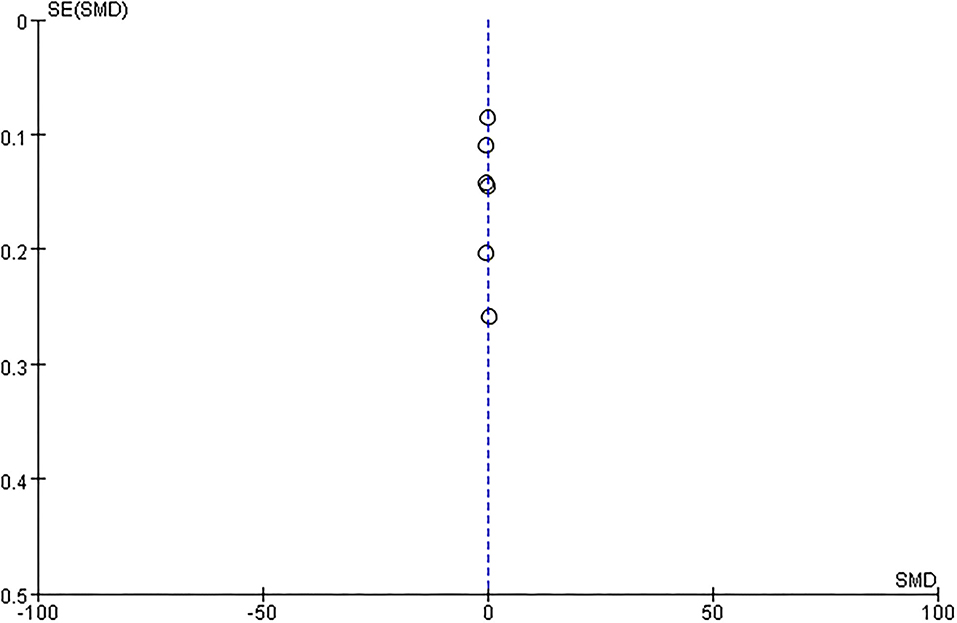

The length of hospital stay was reported in six studies. A meta-analysis of the length of hospital stays using the fixed effect model revealed significant heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 59%); thus, the fixed effect model could not be used. In contrast, analysis using a random-effects model revealed no significant heterogeneity [standardized mean difference (SMD) = −0.13; 95% CI, −0.31 to 0.04; p = 0.14] (Figure 2).

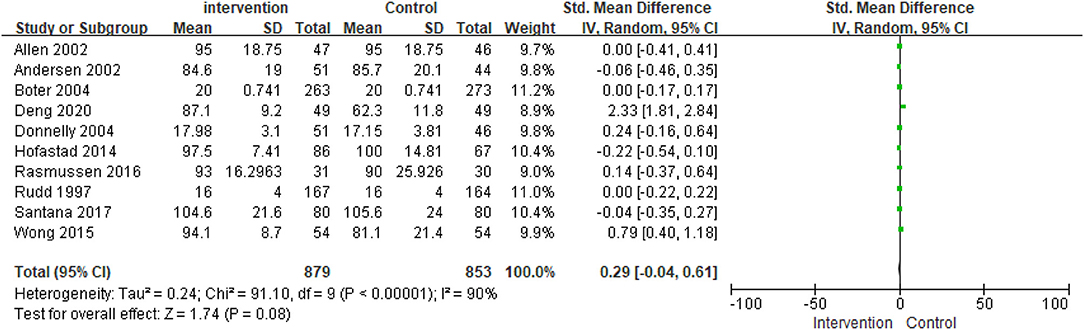

Activities of Daily Living

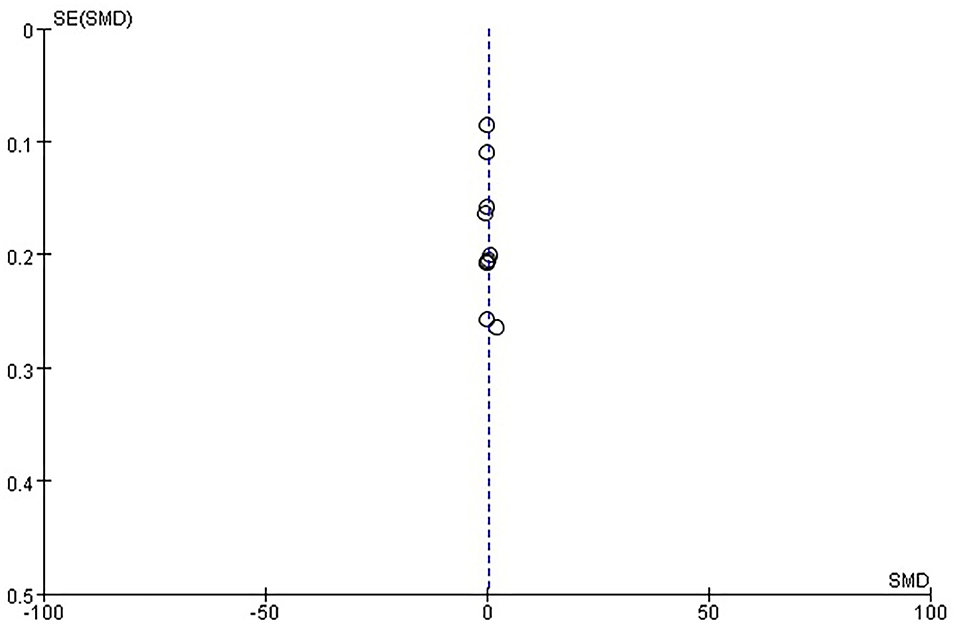

The ADL score was reported in 10 studies. The tool used to measure ADL (Barthel index, Modified Barthel index, Functional independent measure) was different in each of the studies; therefore, the scores were standardized and compared. First, a meta-analysis of ADL using the fixed effect model led to significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 90%; p < 0.000001). Thus, the fixed effect model could not be used. A meta-analysis of ADL using the random-effects model revealed no significant heterogeneity among studies (SMD = 0.29; 95% CI, −0.04 to −0.61; p = 0.08) (Figure 3).

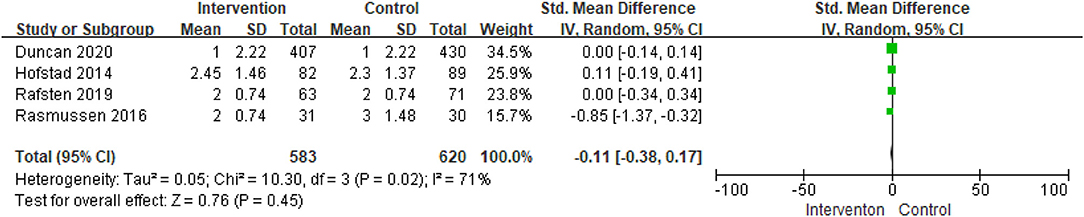

mRS

The mRS score was reported in four studies. Analysis of the mRS scores using the fixed effect model led to significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 71%, p = 0.02). Thus, the fixed effect model could not be used. A meta-analysis of mRS scores using the random-effects model revealed no significant heterogeneity among studies (SMD = −0.11; 95% CI, −0.38 to 0.17; p = 0.45) (Figure 4).

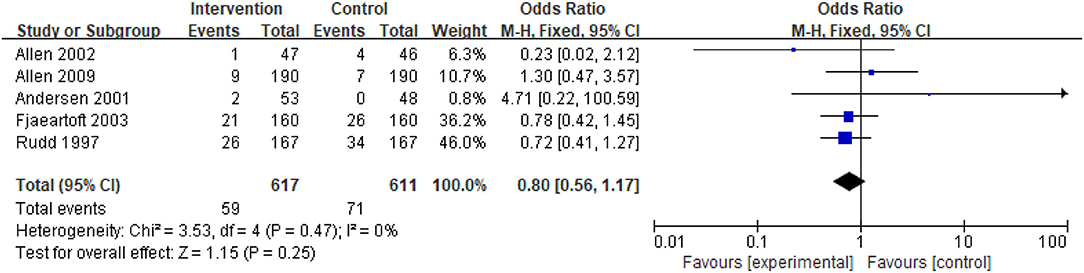

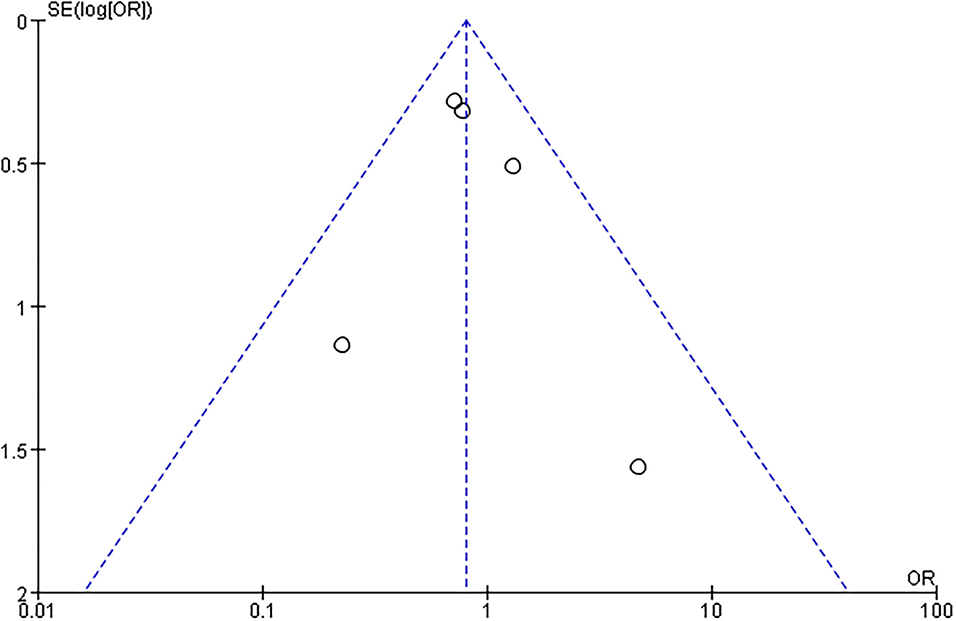

Death

Death was reported in five studies. A meta-analysis of death using the fixed effect model revealed no significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 0%). Thus, the fixed effect model was used. However, the effect size was not significant [odds ratio (OR) = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.56–1.17; p = 0.25] (Figure 5).

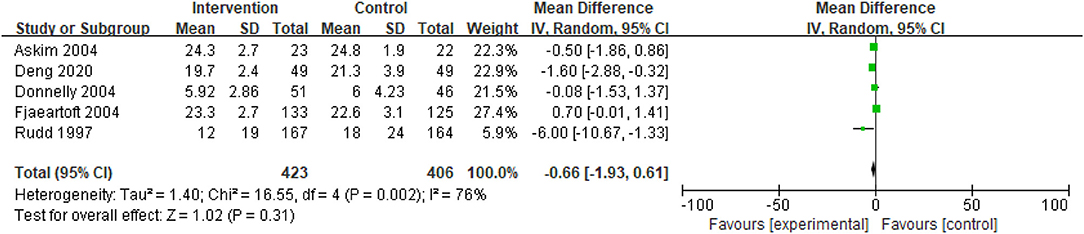

Caregiver Strain Index

Care burden was reported in five studies. A meta-analysis of care burden using the fixed effect model led to significant heterogeneity among studies (I2 = 76%). Thus, the fixed effect model could not be used. A meta-analysis of care burden using the random-effects model revealed no significant heterogeneity among studies (SMD = −0.66; 95% CI, −1.93 to 0.61; p = 0.31) (Figure 6).

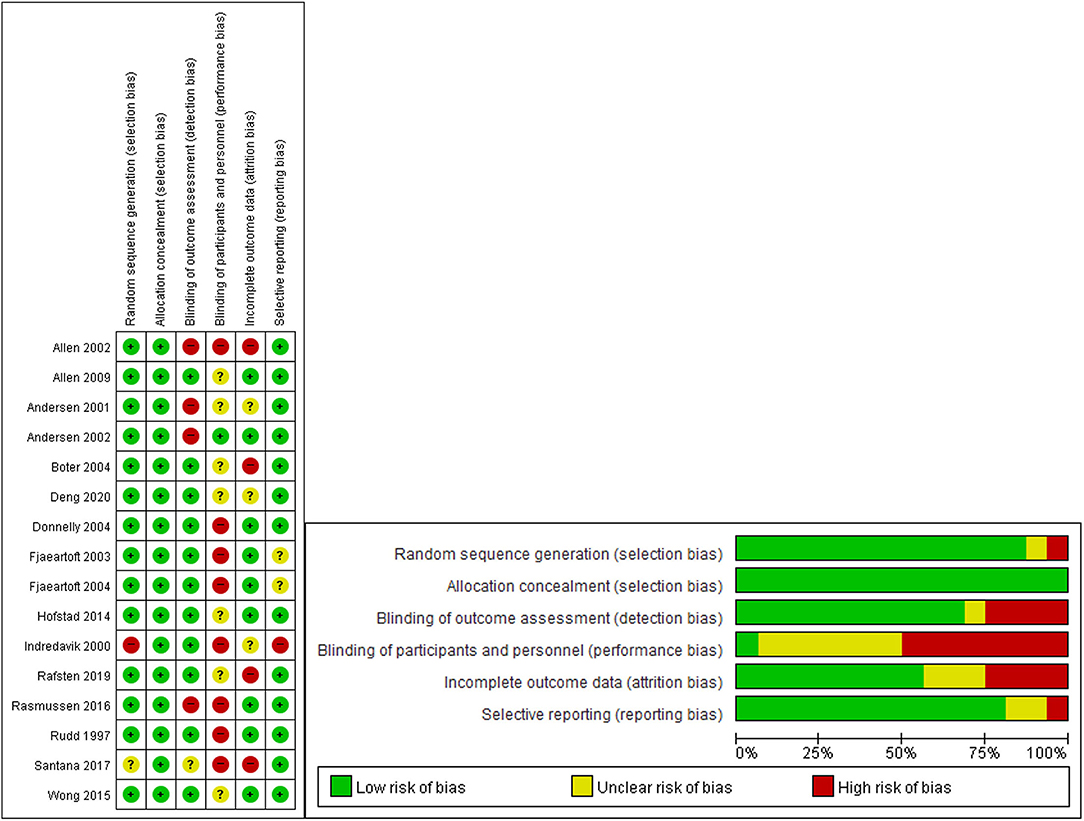

RoB

There were some studies that revealed a high RoB in terms of performance bias, detection bias, and attrition bias. In contrast, the RoB was low for the selection bias and reporting bias. In particular, most studies revealed high or unclear RoB in performance bias (Figure 7).

Figure 7. “Risk of bias” graph: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across included studies. “Risk of bias” summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Publication Bias

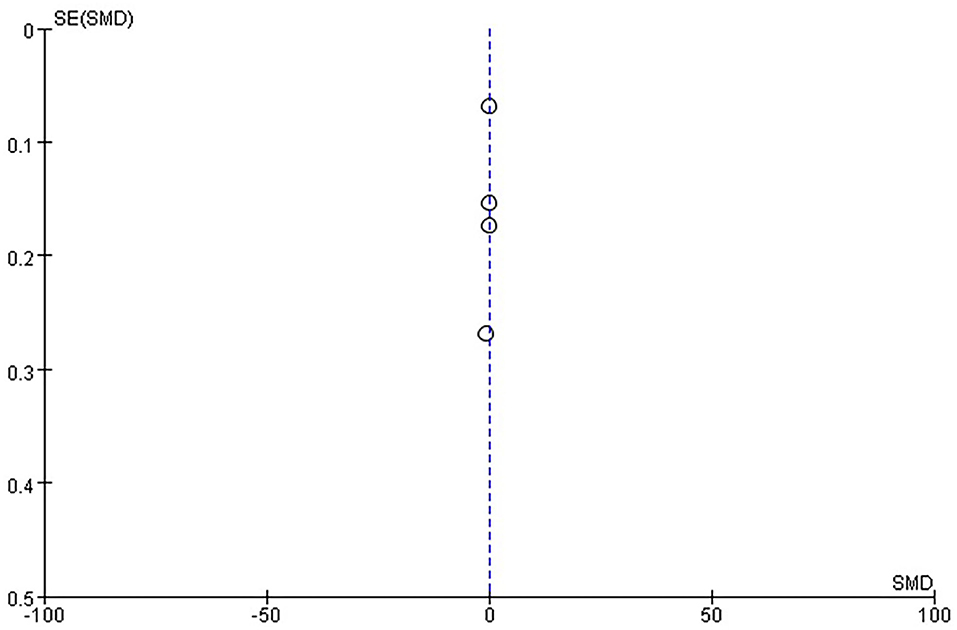

There was no evidence of funnel plot asymmetry for length of hospital stay (Figure 8), ADL (Figure 9), mRS (Figure 10), and death (Figure 11). For the CSI, it was impossible to examine small study bias due to the small number of studies reporting cardiac events.

Figure 9. Funnel plot of comparison: ESD care vs. usual care, outcome: activities of daily living (ADL).

Figure 10. Funnel plot of comparison: ESD care vs. usual care, outcome: modified Rankin scale (mRS).

Discussion

In this study, we systematically reviewed articles on ESD to assess the effects of ESD or TC on ADL, residual symptoms, quality of life, mortality, length of hospital stay, and caregiver burden. A total of 15,118 related studies were searched on three databases. The titles and abstracts were analyzed, and studies that were searched multiple times were excluded. Finally, this systematic literature review examined 20 studies (19 RCTs and 1 RPT). Among these 20 studies, two studies that followed up the participants for more than 5 years and a subgroup study were excluded, and 17 studies were finally included in the meta-analysis. In terms of location, 85, 10, and 5% of the 20 studies were conducted in Europe, Asia, and North America, respectively, demonstrating that ESD is mainly limited to western countries. However, recent studies on ESD have been reported in China, suggesting that ESD programs are also being implemented in Asian countries.

Hempler et al. conducted a systematic literature review of studies on transition management in Germany. A total of 18 studies were included in the literature review; however, there were no high-quality studies on standardized transition management systems, and the literature review study suggested that standardized discharge management services, including ESD programs, are needed in Germany. This finding is consistent with the results of our study, wherein studies conducted in Germany were not included in the meta-analysis. However, countries other than Germany are attempting various types of services, and the services are also gradually being offered in Asian countries, suggesting the need for these services in Korea. Unlike the literature review study conducted in Germany (29), our study is meaningful because two researchers independently selected and evaluated the studies for meta-analysis.

In 2017, Langhorne et al. conducted a literature search similar to our study and performed a systematic literature review and meta-analysis of 17 RCTs that included 2,422 patients. In that study, ESD reduced the length of hospital stay by ~6 days and might have reduced long-term functional dependence. In our study, there was a small number of cases in which ESD led to significant differences in the outcomes. This may be attributed to the homogeneous standard of interventions, excluding patient-led, family-led, and tele-rehabilitation, unlike those used in Cochrane's study, which deliberately set a broad criteria for interventions. Such differences led to exclusion of various studies, which might have led to a reduced number of cases in which ESD significantly improved the study outcomes (6).

We observed no significant differences in ADL between the TC methods, including ESD and conventional treatment. However, several points must be considered in the interpretation of this finding. As shown in the previous meta-analysis (6), ESD was mainly provided to high-level performing stroke patients. Thus, the ADL index included in our analysis might not accurately reflect the ADL functional status of patients due to the ceiling effects. Therefore, future studies must evaluate ADL using indicators that can evaluate high-level functions.

This systematic literature review and meta-analysis is meaningful because the most recent study (9) on TC has been included, and the types of services provided included ESD and TC in the literature search and selection.

However, this study also has several limitations. First, the definition of the interventions was unclear in each study. Thus, the type, duration, and period of intervention, and ESD team members were not completely identical. Second, most studies included in the meta-analysis were blinded to the assessor; however, the study participants could not be blinded. Thus, double-blinded studies could not be included. Third, pragmatic trials reflect realistic medical settings and could be as scientifically essential as an RCT, but it still needs a control group to be able to demonstrate an effect of the intervention. Lastly, we chose a particular set of trials relevant to the Republic of Korea. Therefore, caution is needed when interpreting the results of this study. We considered that TC programs should be a part of the ESD service in our country.

This study systematically investigated the effects of ESD and TC on medical use, function, mortality, and caregiver burden in stroke patients. We did not find a large effect size for the use of TC and ESD. When implementing the TC and ESD model from western to Asian countries, services should be prepared and implemented in accordance with national medical rehabilitation pathways for cerebrovascular disease.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SJ and MS contributed to the conception or design of the work. MJ, WK, Y-IS, and S-HK contributed to the data acquisition. IK, BC, YJ, and WC especially did statistical analysis and interpreted result of data for the work. All authors participated in drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding

This work was supported by the Research Program funded by the Korea National Institute of Health (Grant Number: 2020ER630601).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fneur.2022.755316/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Sall J, Eapen BC, Tran JE, Bowles AO, Bursaw A, Rodgers ME. The management of stroke rehabilitation: a synopsis of the 2019 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Inter Med. (2019) 171:916–24. doi: 10.7326/M19-1695

2. Mountain A, Patrice Lindsay M, Teasell R, Salbach NM, de Jong A, Foley N, et al. Canadian stroke best practice recommendations: rehabilitation, recovery, and community participation following stroke. Part two: transitions and community participation following stroke. Int J Stroke. (2020) 15:789–806. doi: 10.1177/1747493019897847

3. Smith LN, James R, Barber M, Ramsay S, Gillespie D, Chung C. Rehabilitation of patients with stroke: summary of sign guidance. BMJ. (2010) 340:c2845–c. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2845

4. Langhorne P, Holmqvist LW, Early Supported Discharge T. Early supported discharge after stroke. J Rehabil Med. (2007) 39:103–8. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0042

5. Langhorne P, Taylor G, Murray G, Dennis M, Anderson C, Bautz-Holter E, et al. Early supported discharge services for stroke patients: a meta-analysis of individual patients' data. Lancet. (2005) 365:501–6. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17868-4

6. Langhorne P, Baylan S, Early Supported Discharge T. Early supported discharge services for people with acute stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2017) 7:CD000443. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000443.pub4

7. Powers WJ, Rabinstein AA, Ackerson T, Adeoye OM, Bambakidis NC, Becker K, et al. 2018 guidelines for the early management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. (2018) 49:e46–110. doi: 10.1161/STR.0000000000000158

8. Bettger JP, Jones SB, Kucharska-Newton AM, Freburger JK, Coleman SW, Mettam LH, et al. Meeting medicare requirements for transitional care: do stroke care and policy align? Neurology. (2019) 92:427–34. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006921

9. Duncan PW, Bushnell CD, Jones SB, Psioda MA, Gesell SB, D'Agostino RB, et al. Randomized pragmatic trial of stroke transitional care: the compass study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. (2020) 13:e006285. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.006285

10. Askim T, Rohweder G, Lydersen S, Indredavik B. Evaluation of an extended stroke unit service with early supported discharge for patients living in a rural community. A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2004) 18:238–48. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr752oa

11. Fjæartoft H, Indredavik B, Johnsen R, Lydersen S. Acute stroke unit care combined with early supported discharge. Long-term effects on quality of life. A randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2004) 18:580–6. doi: 10.1191/0269215504cr773oa

12. Fjaertoft H, Indredavik B, Lydersen S. Stroke unit care combined with early supported discharge: long-term follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. (2003) 34:2687–91. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000095189.21659.4F

13. Fjærtoft H, Rohweder G, Indredavik B. Stroke unit care combined with early supported discharge improves 5-year outcome: a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. (2011) 42:1707–11. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.601153

14. Hofstad H, Gjelsvik BE, Næss H, Eide GE, Skouen JS. Early supported discharge after stroke in Bergen (ESD stroke Bergen): three and six months results of a randomised controlled trial comparing two early supported discharge schemes with treatment as usual. BMC Neurol. (2014) 14:239. doi: 10.1186/s12883-014-0239-3

15. Indredavik B, Fjaertoft H, Ekeberg G, Løge AD, Mørch B. Benefit of an extended stroke unit service with early supported discharge: a randomized, controlled trial. Stroke. (2000) 31:2989–94. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.12.2989

16. Allen K, Hazelett S, Jarjoura D, Hua K, Wright K, Weinhardt J, et al. A randomized trial testing the superiority of a postdischarge care management model for stroke survivors. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2009) 18:443–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2009.02.002

17. Allen KR, Hazelett S, Jarjoura D, Wickstrom GC, Hua K, Weinhardt J, et al. Effectiveness of a postdischarge care management model for stroke and transient ischemic attack: a randomized trial. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. (2002) 11:88–98. doi: 10.1053/jscd.2002.127106

18. Andersen HE, Eriksen K, Brown A, Schultz-Larsen K, Forchhammer BH. Follow-up services for stroke survivors after hospital discharge–a randomized control study. Clin Rehabil. (2002) 16:593–603. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr528oa

19. Andersen HE, Jurgensen K-L, Kreiner S, Forchhammer BH, Eriksen K, Brown A. Can readmission after stroke be prevented? Results of a randomised clinical study: a postdischarge follow-up service for stroke survivors. Stroke. (2000) 163:6421-7. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.31.5.1038

20. Rasmussen RS, Østergaard A, Kjær P, Skerris A, Skou C, Christoffersen J, et al. Stroke rehabilitation at home before and after discharge reduced disability and improved quality of life: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2016) 30:225–36. doi: 10.1177/0269215515575165

21. Boter H. Multicenter randomized controlled trial of an outreach nursing support program for recently discharged stroke patients. Stroke. (2004) 35:2867–72. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000147717.57531.e5

22. Rafsten L, Danielsson A, Nordin A, Björkdahl A, Lundgren-Nilsson A, Larsson MEH, et al. Gothenburg very early supported discharge study (Gotved): a randomised controlled trial investigating anxiety and overall disability in the first year after stroke. BMC Neurol. (2019) 19:277. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1503-3

23. Thorsén AM, Holmqvist LW, de Pedro-Cuesta J, von Koch L. A randomized controlled trial of early supported discharge and continued rehabilitation at home after stroke: five-year follow-up of patient outcome. Stroke. (2005) 36:297–303. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000152288.42701.a6

24. Donnelly M, Power M, Russell M, Fullerton K. Randomized controlled trial of an early discharge rehabilitation service: the belfast community stroke trial. Stroke. (2004) 35:127–33. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000106911.96026.8F

25. Rudd AG, Wolfe CDA, Tilling K, Beech R. Randomised controlled trial to evaluate early discharge scheme for patients with stroke. Br Med J. (1997) 315:1039–44. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7115.1039

26. Santana S, Rente J, Neves C, Redondo P, Szczygiel N, Larsen T, et al. Early home-supported discharge for patients with stroke in portugal: a randomised controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2017) 31:197–206. doi: 10.1177/0269215515627282

27. Deng A, Yang S, Xiong R. Effects of an integrated transitional care program for stroke survivors living in a rural community: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rehabil. (2020) 34:524–32. doi: 10.1177/0269215520905041

28. Wong FK, Yeung SM. Effects of a 4-week transitional care programme for discharged stroke survivors in hong kong: a randomised controlled trial. Health Soc Care Commun. (2015) 23:619–31. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12177

Keywords: cerebrovascular disease, continuity of patient care, transitional care, rehabilitation, early supported discharge (ESD)

Citation: Jee S, Jeong M, Paik N-J, Kim W-S, Shin Y-I, Ko S-H, Kwon IS, Choi BM, Jung Y, Chang W and Sohn MK (2022) Early Supported Discharge and Transitional Care Management After Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Neurol. 13:755316. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.755316

Received: 08 August 2021; Accepted: 16 February 2022;

Published: 15 March 2022.

Edited by:

Peter Langhorne, University of Glasgow, United KingdomReviewed by:

Noreen Kamal, Dalhousie University, CanadaLena Rafsten, University of Gothenburg, Sweden

Copyright © 2022 Jee, Jeong, Paik, Kim, Shin, Ko, Kwon, Choi, Jung, Chang and Sohn. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Min Kyun Sohn, mksohn@cnu.ac.kr

Sungju Jee

Sungju Jee Minah Jeong1

Minah Jeong1 Nam-Jong Paik

Nam-Jong Paik Won-Seok Kim

Won-Seok Kim Yong-Il Shin

Yong-Il Shin Sung-Hwa Ko

Sung-Hwa Ko Min Kyun Sohn

Min Kyun Sohn