The Jurisdictional Approach in Indonesia: Incentives, Actions, and Facilitating Connections

- 1World Resources Institute, Washington, DC, United States

- 2Terra Komunika, Jakarta, Indonesia

- 3David and Lucile Packard Foundation, Jakarta, Indonesia

As recently as 2014, the “jurisdictional approach” (JA) was an unfamiliar term among organizations working to reduce deforestation and promote sustainable land use in Indonesia. Understood as a more comprehensive approach to low-emissions development than jurisdictional-scale accounting for REDD+, JA was seen as a way to address challenges faced by early efforts to implement corporate commitments to deforestation-free supply chains. JA initiatives sought to align government-led, multistakeholder processes within provinces and districts with prospective external incentives for jurisdictional-scale performance. By early 2020, elements of the concept had been incorporated into official plans and regulations in several provinces and districts and was recognized in the government’s national medium-term development plan. Over the intervening years, the community of JA proponents and practitioners had grown rapidly and coalesced around a common understanding of what the approach entails. Credible, locally led JA initiatives were underway with international support in at least a dozen provinces and districts, and a national platform had been established to link districts that had committed to sustainability. Those initiatives were accompanied by active discourses on proposals for fiscal transfers and preferential market access to provide incentives for improved jurisdictional-scale performance based on indicators such as reduced deforestation. While it is too early to assess the ability of JA to generate significant results, practitioners have identified a number of constraints. Those include still-limited material incentives for change compared to the factors that drive business-as-usual deforestation, limited availability of spatial data for better land-use planning, low capacity of district-level officials, and misalignment of government policies between subnational and national entities and across ministries. In order to adequately test the JA theory of change, greater emphasis on creating external incentives and linking JA initiatives across jurisdictions and scales is needed to complement the facilitation of activities within individual provinces and districts.

Introduction

Indonesia has emerged as a globally significant laboratory for early experimentation with the so-called jurisdictional approach (JA) to more sustainable and equitable land use. While JA builds on a long history of land-use planning efforts in Indonesia and elsewhere, its innovative feature is the attempt to align government-led, multistakeholder processes within provinces and districts with prospective external financial and market incentives for jurisdictional-scale performance on indicators such as reducing deforestation while also meeting social and economic objectives. These initiatives have collectively spanned—and begun to integrate—REDD+, commodity supply chain initiatives, and domestic policies and finance toward common metrics of performance at jurisdictional scale (Nepstad et al., 2013).

The purpose of this paper is to summarize the development and current state of JA in Indonesia and to identify challenges constraining further progress. As recently as 2014, the “jurisdictional approach” was a new, unfamiliar, and contested term among domestic and international organizations working on initiatives to reduce deforestation and promote sustainable land use in Indonesia. Over the next 6 years, the community of JA proponents and practitioners grew rapidly and attracted interest from government and corporate officials. JA was understood as a more comprehensive approach to low-emissions development than jurisdictional-scale accounting for REDD+1 (Nepstad et al., 2012). JA gained steam as a way to address challenges faced by early efforts to implement corporate commitments to deforestation-free supply chains (Taylor and Streck, 2018). In Indonesia, that meant a particular focus on palm oil, as subnational governments exercised significant influence over licensing of oil palm plantations in forested areas.

Consistent with the emerging literature on JA, we restrict the term in several ways (Nepstad, 2017; Paoli and Palmer, 2017; Boyd et al., 2018). First, we limit JA to initiatives that address land-use challenges in areas that are defined by the boundaries of political/administrative jurisdictions. Second, we include in our definition of JA initiatives that are anchored in relevant jurisdictional-scale government agencies and involve multiple stakeholder groups. Thus, we exclude projects focused on “landscapes” that do not conform to one or more jurisdictional boundaries and activities not linked to local government. Third, for the purposes of this paper, we focus on subnational jurisdictions one and two levels down from the national scale in Indonesia, i.e., provinces and districts (kabupaten), recognizing that the country of Indonesia as a whole, subdistricts (kecamatan), and villages (desa) are also jurisdictions. This choice is consistent with the analysis of Irawan et al. (2019) demonstrating the potential of provincial- and district-level governments to contribute to national-level targets to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from deforestation.

The paper draws primarily on information and insights gained from the authors’ participation in activities supported by the David and Lucile Packard Foundation and Climate and Land Use Alliance (CLUA), which included roles as grantees and consultants focused on promoting JA in Indonesia. JA was one of seven elements included in the Foundation’s 2014 strategy to reduce deforestation and peatland conversion caused by the expansion of oil palm plantations (Seymour, 2014) and one of the four targeted outcomes of the Foundation’s revised palm oil strategy for 2018–2021 (Morris, 2018). The approach was incorporated into the Indonesia initiative of CLUA, a collaborative of foundations that seeks to support sustainable land use as an essential part of the global response to climate change (Climate and Land Use Alliance [CLUA], 2018).

The paper begins with a brief description of the Indonesian context for JA in terms of the history of deforestation and decentralization. It then describes the origins and entry points of the first generation of JA initiatives. Subsequent sections introduce a simple analytical framework that distinguishes among three types of JA initiatives and uses that framework to assess recent progress achieved and challenges faced by these initiatives. The paper closes with discussions of constraints on assessing impact and actionable recommendations and suggests how Indonesia can contribute to, and benefit from, the current global discourse on JA and associated community of practice.

The Context for JA in Indonesia

The jurisdictional approach in Indonesia targets the long-standing problems of deforestation and peatland conversion, with a focus on the country’s forest-rich outer islands, including Sumatra, Sulawesi, and the Indonesian portions of Borneo and New Guinea. Commercial-scale exploitation of these forests for timber dates back to the late 1960s, when the forestry sector provided an early source of finance to President Suharto’s highly centralized “New Order” regime and was abetted by the advice of international financial institutions for servicing debt and Japan’s demand for tropical timber (Dauvergne, 1993). Over the past four decades, forest loss and peatland degradation have unfolded through a complex interplay among ever-changing political, economic, and biophysical causes.

Forest Exploitation Under the Suharto Regime

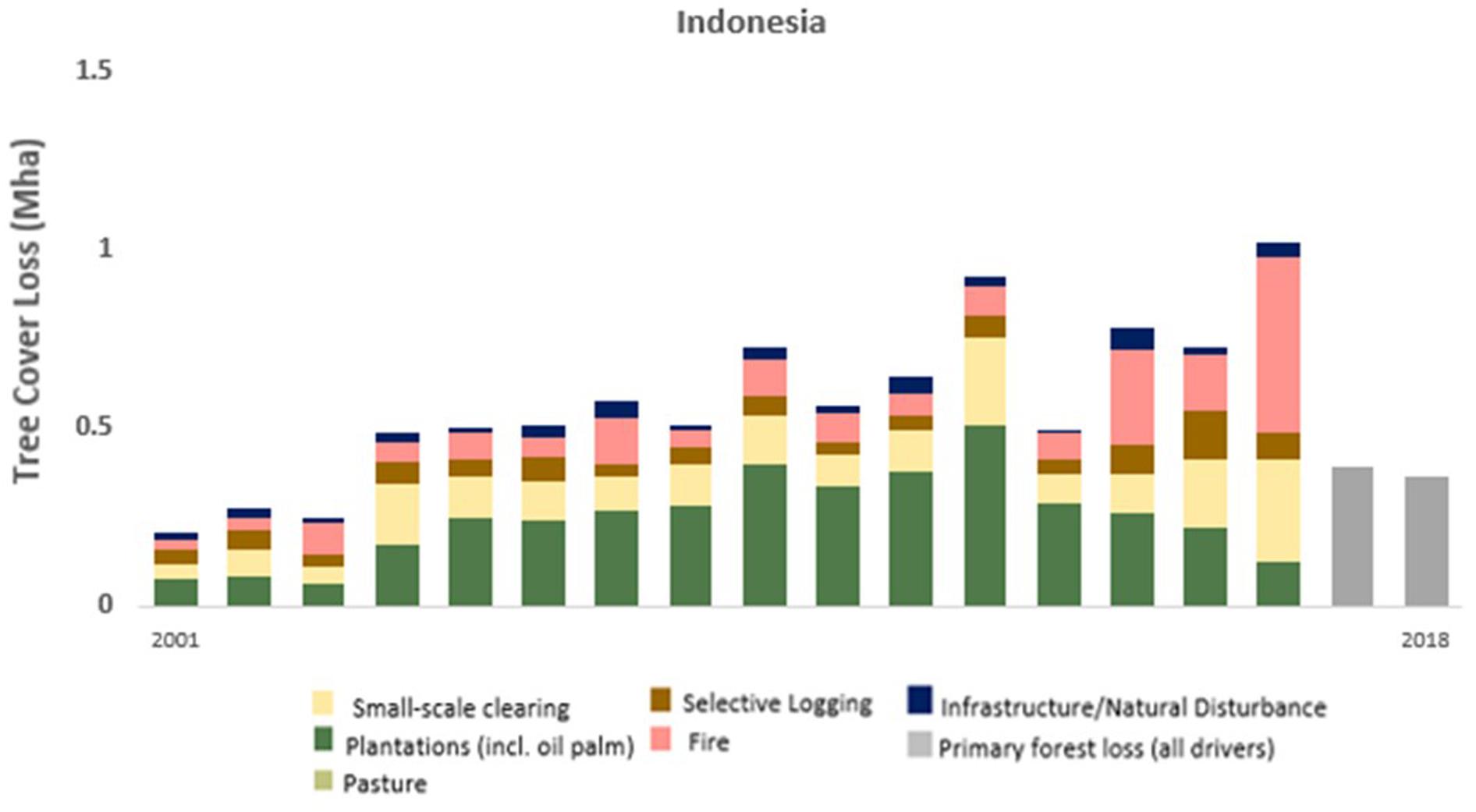

Although comparable and reliable data on the extent and drivers of tree cover loss based on satellite imagery extend back only to 2001 (Hansen et al., 2013), a stylized recounting of deforestation in Indonesia starts with the logging of lowland dipterocarp forests. More than 500 timber concessions covering almost 100 million hectares were granted to military interests, senior bureaucrats, and other “crony capitalists” in the late 1960s and 1970s by the national forestry agency, which became a separate ministry in 1985 (Dharmasaputra and Wahyudi, 2014). In the 1980s, the focus shifted to extracting timber to support wood processing industries, as Indonesia became the world’s largest plywood manufacturer. In the 1990s, the focus shifted again to the pulp and paper sector, which initially sourced significant feedstock from natural forests while plantations of fast-growing timber were still under development. In the 2000s, expansion of oil palm plantations into forests and peatlands emerged as a key driver of deforestation. Figure 1 depicts the drivers of primary forest loss in Indonesia, 2001–2018.

Figure 1. Annual primary forest loss area by disturbance driver in Indonesia, 2001–2018 (Source: Austin et al., 2019).

This large-scale exploitation of Indonesia’s forests transformed the physical landscape. Regulations designed to ensure sustainability of the timber harvest were poorly enforced, leaving behind damaged and fire-prone forests. Clearing and draining of Indonesia’s peatlands to make way for timber and oil palm plantations disrupted local hydrology and compounded the risk of fire, culminating in the catastrophic fire and haze of 1997–1998.

Natural resource exploitation also shaped the landscape of Indonesia’s political economy. Many of Indonesia’s largest personal fortunes were amassed through unsustainable exploitation of Indonesia’s forest resources, which was controlled by a limited number of large conglomerates with close ties to the regime (Dharmasaputra and Wahyudi, 2014). At the same time, the rights of indigenous peoples whose customary territories covered much of Indonesia’s forest area were ignored, as their land and forests were distributed to license holders and migrants from Java and Bali (Dauvergne, 1993).

Commitments to Forest Protection

Under the Presidency of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, Indonesia positioned itself on the international stage as committed to reducing deforestation in the context of climate action, starting with its hosting of the Conference of the Parties (COP) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Bali in 2007. At the 2009 meeting of the Group of 20 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, President Yudhoyono made a speech committing Indonesia to an emissions reduction target—the first developing country to do so—that could only be reached by dramatically reducing emissions from deforestation. The following year, the Government of Indonesia entered into a US$1 billion bilateral agreement with the Government of Norway to reduce forest-based emissions, which included a moratorium on new licenses to exploit primary forests and peatlands.

Early in the Presidency of Joko Widodo (“Jokowi”), Indonesia experienced the catastrophic forest and peatland fires of 2015, which inflicted significant costs on the economy and the public health of the region. New policies were rolled out in the aftermath of the fires, including extending the scope of the moratorium to include a ban on further development of peatlands and licensing for oil palm plantations. A significant drop in the rate of tree cover loss in 2017 and 2018 compared to previous years—including an 80% drop in deep peatland and a 40% drop in primary forests protected by the moratorium (Weisse and Goldman, 2019)—suggests that these policies had an effect. Although favorable weather and low commodity prices also no doubt contributed, the lower rates of forest loss were maintained in 2019 (Weisse and Goldman, 2020).

Democratization and Decentralization

After the fall of President Suharto in 1998, decentralization was an early focus of the nation’s efforts toward democratization. In 1998, a decree by the national parliament calling for regional autonomy was quickly followed by two laws in 1999 (Laws 22 and 25) that devolved significant government functions to the district level and governed revenue sharing across levels (Government of Indonesia, 1999a, b). Devolution of authority included natural resources management, increased subnational share of revenues from natural resource exploitation, and altered accountability relationship between provinces and districts in ways that led to prioritization of economic gain at the expense of conservation objectives (Resosudarmo, 2004). A 1999 decree authorized provinces and districts to grant permits for small-scale timber harvesting, resulting in a frenzy of logging, later curtailed in a 2002 Ministerial decree (Moeliono et al., 2009).

Later in 1999, a new forestry law was passed that was inconsistent with the decentralization laws and served as the basis for the Ministry of Forestry’s attempts to recentralize control over forests (Barr et al., 2006). Prior to the decentralization laws (which were themselves ambiguous), legal ambiguity had already been created by the 1992 Law on Spatial Planning, which provided provinces with an opportunity to prepare land-use plans that diverged from the Consensus-Based Forest Land-Use Plans (Tata Guna Hutan Kesepakatan, or TGHK) and maps issued by the Ministry of Forestry under the 1967 Basic Forest Law (Setiawan et al., 2016). Encouraged by decentralization laws and the priority given to development of the palm oil industry by other national ministries, local officials used legal ambiguity to issue permits for oil palm plantations in designated forest areas. In Central Kalimantan, this defiance of the Ministry of Forestry’s authority was eventually rewarded with a negotiated compromise in 2011, in which more than a million hectares of forest land were released from the forest estate, an effective amnesty for the irregularly issued permits (Gellert and Andiko, 2015; Setiawan et al., 2016). The case illustrated a more general lack of coherence and coordination in forest management policy and authority both vertically across levels of government and horizontally across ministries (Barr et al., 2006).

The ongoing struggle for control over forest-based natural resources, characterized as an intense “tug of war” between the Ministry of Forestry and local governments (Resosudarmo, 2004), continued in subsequent years. A revised decentralization law passed in 2004 reallocated some land management functions across levels, and a 2007 Ministerial regulation initiated the creation and regulation of forest management units (Moeliono et al., 2009). These units (Kesatuan Pengelolaan Hutan, or KPH) created a new arena for contesting power over forests, including the various administrative avenues for recognizing community forest management, across central, provincial, district, and village levels (Sahide et al., 2016). A further revision of the decentralization law in 2014 shifted the authority to issue logging, mining, and fisheries licenses from the district to the provincial level, leaving licensing for oil palm and other agricultural commodity crops in the hands of district-level authorities (Government of Indonesia, 2014). Most recently, in early 2020, a proposed omnibus bill on job creation threatened to weaken the role of local governments in spatial planning (Eloksari, 2020).

In the meantime, many forest-rich provinces and districts were being subdivided in a process called pemekaran to create new autonomous units. For example, West Papua was divided from Papua in 2003, and North Kalimantan was divided from East Kalimantan in 2012. More than 170 new districts have been created nationwide since 19992.

The history and context sketched above both motivates and constrains JA in Indonesia. Because provincial- and district-level governments wield significant authority over land-use decision-making and resource allocation (Irawan et al., 2019), a focus on improving land-use planning and enforcement at those levels is a critical component of the JA theory of change. At the same time, this history has left most jurisdictions with challenges locked in by previous land-use policies. Such legacies include highly altered and often fire-prone landscapes, long-term concession agreements and installed processing capacity, contested decision-making authority across government levels and agencies, long-simmering conflicts and competing claims to land, and mistrust among stakeholder groups.

Antecedents of JA in Indonesia

Current JA activities in Indonesia build on a long history of attempts to strengthen local government and land-use planning at the subnational level. In the late 1970s, international donors supported the national government’s Provincial Development Programmes (PDP) in 11 provinces, including Aceh and East Kalimantan (Ramachandran and de Campos Guimaraes, 1991). The PDP were designed to strengthen planning capacity at provincial and district levels for integrated rural development. The German government’s participation in the PDP in Kalimantan provinces extended through various initiatives up to the present FORCLIME3 project, which is active in strengthening institutions for forest management in districts in North, East, and West Kalimantan as well as in Central Sulawesi.

In the 1980s, the Ministry of Forestry’s social forestry program, supported by the Ford Foundation, included multistakeholder working groups in four outer island provinces to improve community participation in forest management. The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) implemented an action research agenda in the Malinau District of what is now the province of North Kalimantan in the wake of the late 1990s decentralization and supported the district head in his declaration of a “Conservation District” in Moeliono (2006). The Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) facilitated joint declarations to conserve critical ecosystems at the landscape scale among leaders of Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei in the Heart of Borneo Initiative in 2007 (World Wildlife Fund, 2007) and among the governors of Sumatra’s 10 provinces in 20084.

Antecedents in REDD+

In Indonesia, as elsewhere, it was the international discussions of REDD+ under the UNFCCC that propelled significant attention to the role of subnational governments in forest management. Although most early REDD+ initiatives were at the level of individual projects, and negotiations that would establish REDD+ accounting and finance at jurisdictional scale would not be completed until 2013, subnational leaders showed active interest from the beginning (Seymour and Busch, 2016).

Governors from the Indonesian provinces of Aceh and Papua were among the participants in a 2008 meeting in California convened by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger that led to the launch of the Governors Climate and Forest Task Force (GCFTF)5, and seven Indonesian provinces eventually became members. The GCFTF provided assistance and training to government officials in member provinces in areas such as measurement, reporting, and verification (MRV) of forest-based emission reductions in order to qualify for REDD+ finance, as well as more general support for transitioning to low-emissions development pathways. In 2009, The Nature Conservancy (TNC) launched a jurisdictional-scale REDD+ initiative in conjunction with the head of Berau District in East Kalimantan.

Indonesia’s national REDD+ Task Force, established in 2011 following the signing of the REDD+ agreement with the Government of Norway mentioned above, announced a “One Map Policy” intended to support better subnational land-use planning through resolution of conflicting maps issued by different sectoral agencies. The Task Force also developed a strategy that included implementation and monitoring at the provincial level. The Task Force designated Central Kalimantan as the first pilot province in 2012 and established a joint secretariat with the provincial government. An additional 10 provinces, including Aceh, West Sumatra, Jambi, South Sumatra, West Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, Central Kalimantan, Papua, and West Papua, were each supported to develop a REDD+ Provincial Action Plan and Strategy (Strategi dan Rencana Aksi Provinsi or SRAP), although not all were completed nor integrated into regional development plans and budgets (Ekawati et al., 2019).

After transitioning briefly to an independent agency under President Yudhoyono, Indonesia’s national REDD+ program was subsumed into the climate change directorate of the new Ministry of Environment and Forestry created in late 2014 after President Jokowi assumed office. Thereafter, the REDD+ agenda appeared to at least temporarily run out of steam, mirroring a decline in enthusiasm for REDD+ internationally. Nevertheless, provincial-level REDD+ activities supported through the GCFTF and the national REDD+ program had created institutional infrastructure and human resources that could later be leveraged to support JA.

Antecedents in Deforestation-Free Commodity Supply Chain Commitments

Another antecedent to JA in Indonesia was the early experience of companies attempting to implement commitments to get deforestation out of commodity supply chains, especially for palm oil. In late 2013, Wilmar International, a major palm oil trader and producer, bowed to pressure from activists and announced a No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation (NDPE) policy (Wilmar International, 2013). Other companies soon followed, and at the UN Climate Action Summit in September 2014, they announced a collective commitment to work together to fulfill an Indonesian Palm Oil Pledge (IPOP). The IPOP established a secretariat, which developed programs to assist companies in implementing their commitments, including coordination at the subnational level in three provinces. However, within two years, IPOP was forced to disband under pressure from the national government, which saw IPOP as an unacceptable usurpation of the government’s policy-making role (Dermawan and Hospes, 2018).

The IPOP experience put a sharp focus on the political importance of government leadership in the shift to deforestation-free supply chains. In the meantime, a growing number of participants in that effort had begun to appreciate the practical limitations of an approach limited to voluntary actions by private corporations. They realized that even if the committed companies all fulfilled their pledges within their supply chains, rogue companies could continue to clear forests—even those set aside by responsible companies—and sell the resulting products to environmentally insensitive markets (Seymour, 2017). A jurisdictional approach—one that would involve the government’s authority to make and enforce land-use policies and apply those policies throughout a jurisdiction—thus appeared to address two constraints on the potential success of the sustainable supply chain movement.

More recently, the government’s own approach to achieving sustainability in the palm oil sector was downscaled to the district level. In 2014, the Indonesian Ministry of Agriculture established a National Forum on Sustainable Palm Oil (FoKSBI) to coordinate multistakeholder activities to implement a National Action Plan (NAP) at national and subnational levels. In 2018, the districts of Siak and Pelalawan in Riau Province were selected as NAP pilots (Saragih, 2019).

Antecedents Related to Indigenous Rights

A third antecedent to the emergence of JA in Indonesia (although its potential has not yet been realized) was precipitated by a 2013 Constitutional Court ruling that opened the door to recognition of indigenous peoples’ rights to forest land. The ruling was the result of a suit brought by the Aliansi Masyarakat Adat Nusantara (AMAN), a national federation of indigenous communities, challenging the national government’s control over customary territories, or adat land, within the forest estate according to the 1999 Forestry Law. The ruling had special resonance in the provinces of Papua and West Papua, which had been granted “special autonomy” status under a 2001 law and subsequent government regulation. Special autonomy recognizes the need for local governments to be able to respond to unique circumstances and customary laws of indigenous Papuans (Fatem et al., 2018).

Following the Constitutional Court ruling, the government passed responsibility for recognizing adat communities and territories to legislative action at the district level. Several important precedents were set under this mechanism, including a decree recognizing an Indigenous Forest within a national park, and another in an area covered by a timber concession (Fay and Denduangrudee, 2018). Over the course of 2018 and 2019, AMAN facilitated the promulgation of local regulations (Peraturan Daerah) to provide the basis for recognizing indigenous customary rights in dozens of districts across Indonesia (AMAN, 2020). These developments strengthened the case for focusing on subnational jurisdictions as the most strategic scale for resolving long-standing conflicts over rights to forest land.

Early JA Initiatives and Discourses

The antecedents described above provided various entry points through which a set of jurisdictional-scale engagements began to coalesce into a JA community of practice in Indonesia around 2013 and 2014. The New York Declaration on Forests, endorsed at the same 2014 UN Summit that gave birth to IPOP, aligned the commitments of dozens of national and subnational governments, multinational corporations, non-governmental organizations, and federations of indigenous communities around 10 goals to stop deforestation by 2030 (NYDF Partners, 2019). The emergence of JA as “something new” in Indonesia can be understood as a national reflection of the Declaration’s explicit adoption of a multistakeholder approach and the weaving together of multiple international initiatives to address deforestation, including the provision of financial and market-based incentives and strengthening indigenous rights. Four early examples of JA were characterized by district-level activities nested within a provincial-scale initiative.

REDD+ provided the entry point for one of Indonesia’s first JA initiatives, which focused on the province of East Kalimantan. In November of 2014, TNC hosted a workshop in Jakarta to present and discuss a global study on jurisdictional approaches to REDD+ and low-emissions development programs (Fishbein and Lee, 2015). The study drew in part on TNC’s long-standing engagement in the district of Berau in East Kalimantan and especially the Berau Forest Carbon Program. TNC also promoted JA at the provincial level in East Kalimantan, supporting Governor Awang Farouk Ishak’s ambitions for low-carbon development through a provincial climate change council (Adams and Algamar, 2016). The governor hosted the annual global meeting of the GCFTF in Balikpapan in 2017, at which a provincial “Green Growth Compact” announced the previous year was signed by dozens of stakeholders and international supporters (Komalasari et al., 2018).

Bridging REDD+ and commodity supply chain antecedents was the Earth Innovation Institute (EII), a US-based organization with experience in jurisdictional approaches in Brazil. In 2013, EII engaged with Teras Narang, Governor of Central Kalimantan province, to develop a “Roadmap to Low-Deforestation Rural Development” (Irawan et al., 2014). While the collaboration started through the governor’s engagement with the GCFTF and Central Kalimantan’s status as a REDD+ pilot, EII’s Indonesian partner organization, Yayasan Penelitian Inovasi Bumi (INOBU), focused on district-level pilots to achieve sustainable palm oil production at jurisdictional scale in Seruyan, Kotawaringan Barat, and Gunung Mas. In 2014, the district head of Seruyan, Sudarsono, announced his support, and a program of mapping smallholder plantations ensued. In 2016, the initiative received the backing of IPOP. INOBU then brokered a sourcing agreement between a group of smallholders in Kotawaringan Barat and Unilever, which had committed in 2015 to move toward preferential sourcing from jurisdictions making progress toward sustainability (Unilever, 2017).

A third example dating from 2014 also focused on a transition to sustainable palm oil production, in this case in the province of South Sumatra. There, the Netherlands-based Sustainable Trade Initiative (IDH) initiated work on a green growth strategy in partnership with the provincial government and the World Agroforestry Centre (ICRAF). As with the EII/INOBU initiative in Central Kalimantan, the objective of the partnership was to achieve sustainable palm oil production at jurisdictional scale with an initial focus on Lalan subdistrict in the district of Musi Banyuasin (IDH, 2016). The collaboration resulted a Green Growth Plan for South Sumatra signed by the governor in 2017 and development of a supportive multistakeholder coalition.

A fourth example dates from 2013, when a coalition of international and domestic civil society organizations (CSOs) began working with the head of the newly established Tambrauw District in West Papua province, much of which was zoned as strict “conservation forest” (Samdhana Institute, n.d.). The newly elected district head had proposed establishing Tambrauw as a “Conservation District,” with “adaptive management” of conservation forest as a way of balancing biodiversity conservation objectives with economic development (Fatem et al., 2018). The CSOs, who were focused on assisting adat communities in the district to secure their land rights, formed a “Development Partnership” with the district and supported the formulation of two draft local regulations, one establishing the conservation district and one recognizing the rights of adat communities (Fatem et al., 2018). An important contribution of the CSOs was the participatory mapping of customary territories to inform indicative maps for land-use zoning (Samdhana Institute, n.d.).

Consolidation of the JA Concept

Since the earliest efforts to develop the concept and practice of JA in Indonesia, a common understanding of what was meant by “JA” gradually emerged among civil society proponents, government officials, private companies, international donor agencies, and other partners working in Indonesia (Seymour and Aurora, 2019). Such a common understanding underpinned an informal community of practice among organizations and individuals working to advance the concept within specific jurisdictions and institutions, as well as to develop a supportive enabling environment and incentives at national and international levels. Companies began to recognize the potential of JA to assist them in meeting their NDPE commitments across a supply base extending beyond their own operations to include small- and medium-sized companies and smallholders.

This development was significant, as for several years, there was confusion over the degree to which project-scale or sector-specific initiatives “counted” as JA. There were debates among CSOs over terminology (e.g., JA vs. “landscape” and “territorial” alternatives) and the most appropriate translation into the Indonesian language. An important indicator of progress in mainstreaming the concept into national development policy and practice was the integration of JA (translated as Pendekatan Yurisdiksi Berkelanjutan) into Indonesia’s 2020–2024 Medium Term Development Plan (Government of Indonesia, 2020).

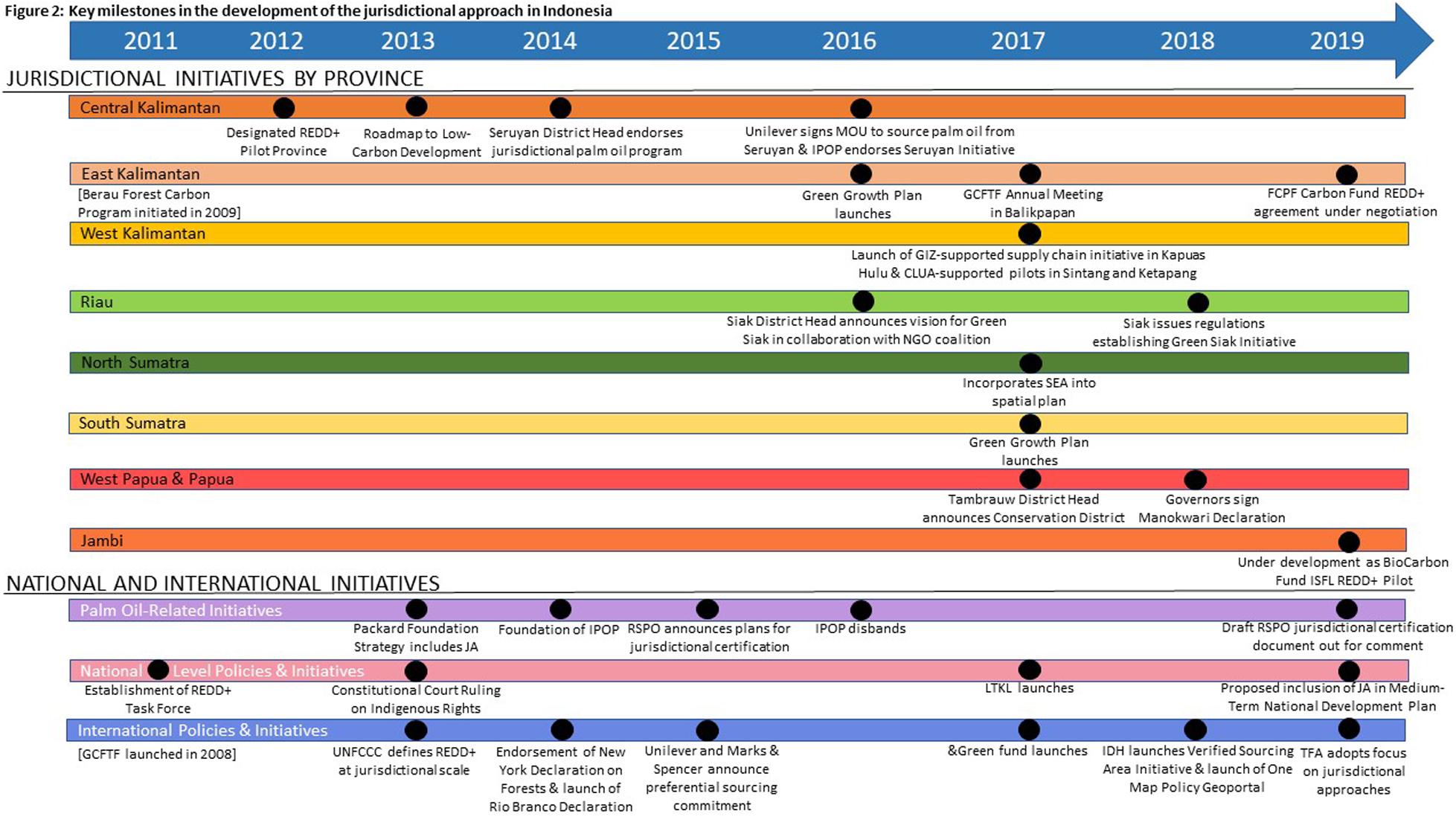

Figure 2 illustrates key milestones in the development of JA in Indonesia.

Analytical Framework

An emerging literature on JA at the global level has advanced various analytical frameworks and theories of change for understanding how JA could catalyze transformation toward sustainability in the land-use sector. Nepstad et al. (2013); Paoli et al. (2016) identify the need for a “value proposition” sufficiently material to the interests of jurisdictional leaders to motivate change, combined with the establishment of multistakeholder structures and processes to coordinate action. Boyd et al. (2018) similarly distinguish between factors external and internal to the jurisdiction leading to performance. Boshoven et al. (in review) focus on how a “global value proposition” created by preferential sourcing of deforestation-risk commodities from high-performing jurisdictions articulates with local interests. Such market-based incentives are expected to complement incentives provided by performance-based REDD+ finance, for which the theory of change has evolved (Angelsen and McNeill, 2012) and has been critiqued (Martius et al., 2018).

Hovani et al. (2018a) place more emphasis on cultivating “collective systems leadership” among actors within jurisdictions, with less reliance on external incentives. While it is indeed the case that action in a few jurisdictions in Indonesia has been motivated by internal factors, e.g., a desire to control land fires caused by forest and peatland degradation, in many other cases, it has proven difficult to gain or sustain traction for JA initiatives in the absence of at least the prospect of external reward.

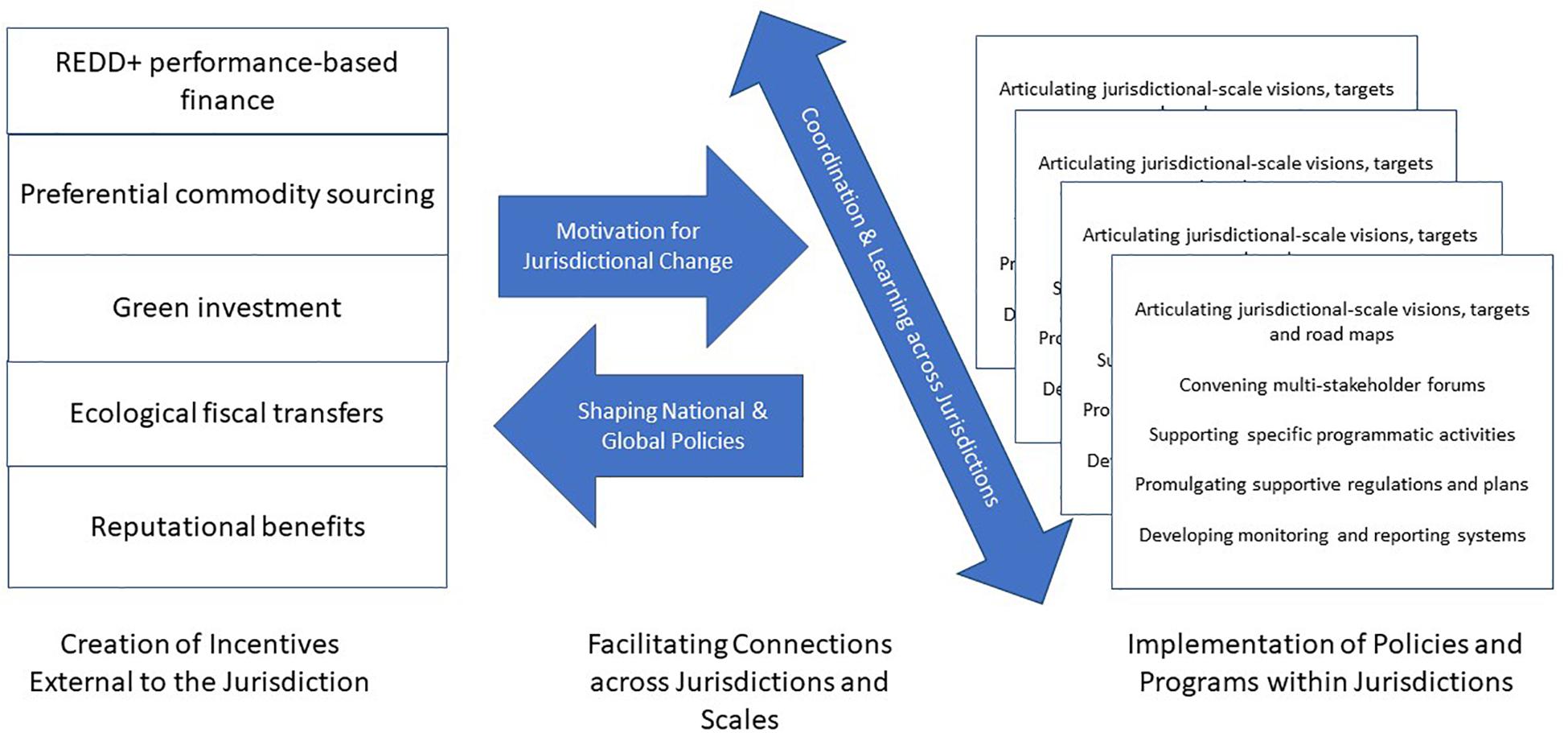

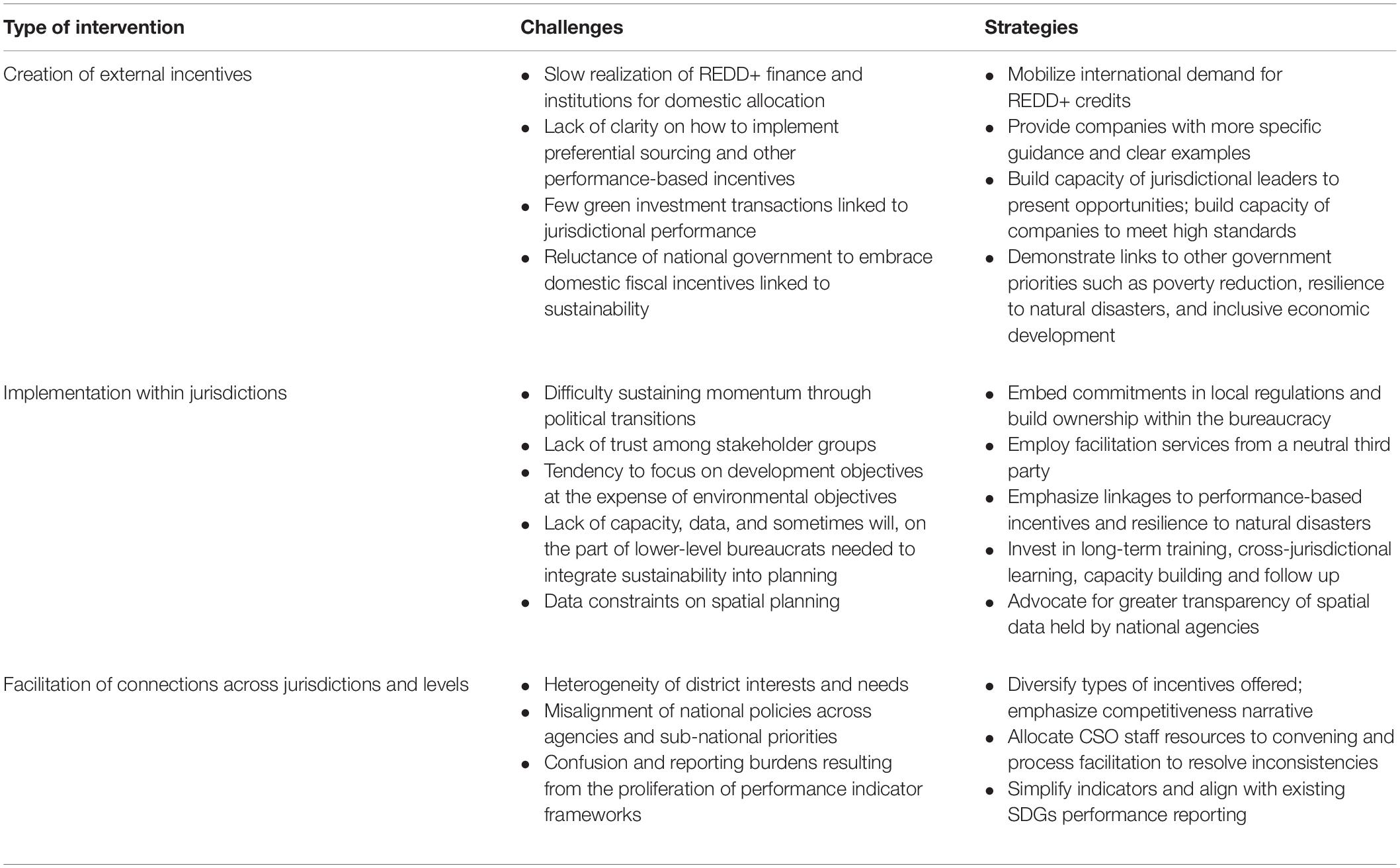

For the purpose of analyzing the progress of JA in Indonesia, we adopt a simple three-part framework that builds on and adds to those analyses. We distinguish among three types of (not mutually exclusive) JA initiatives:

• Those that focus on creating incentives (or “value propositions”) external to individual jurisdictions (adapted from Boyd et al., 2018);

• Those that focus on facilitating activities within individual jurisdictions to build political will and capacity for implementation (adapted from Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari [LTKL], 2019c); and

• Those that focus on facilitating connections between the first two types of initiatives vertically across levels, as well as horizontally across jurisdictions at the same level.

Figure 3 illustrates how these three approaches relate to each other.

In the following three sections, we describe each type of initiative, provide illustrative examples, and highlight associated progress and challenges reported by JA proponents.

Initiatives Focused on Creating External Incentives

One of the key findings of the Daemeter Consulting JA scoping study (Paoli et al., 2016) was the lack of a clear value proposition for subnational political leaders in Indonesia to undertake a transition to low-carbon development. Political, economic, and financial incentives are for the most part stacked in favor of deforestation-as-usual policies and practices. Even though most revenues from forest exploitation are captured at the national level, local governments nevertheless derive benefits from forest exploitation and conversion (Irawan et al., 2013). Encouraging migration into forest areas means more voters; converting forests to plantations means more local employment and revenue, in the form of both legal taxes and fees and illicit payments. Studies have found a positive correlation between local election cycles and illegal logging and deforestation (Burgess et al., 2011; Adrison, 2013).

Two of the main antecedents of JA in Indonesia, namely REDD+ (and associated performance-based finance) and commodity supply chain commitments (and associated preferential sourcing), were expected to provide material incentives to subnational jurisdictions for performance in reducing deforestation. However, the international frameworks needed to provide these incentives have been slow to develop and connect to subnational jurisdictions (Seymour and Harris, 2019), so their value propositions remain mostly in prospect, as described below. In the meantime, donors and CSOs have pushed for adoption of complementary domestic fiscal policies to reward performance as an alternative source of external incentives for change. JA proponents have recognized that local leaders are also interested in attracting green investment and reputational benefits.

REDD+ Performance-Based Finance

The prospect of REDD+ finance provided an entry point for some of the earliest JA initiatives in Indonesia—see Box 1 on Green Development in East Kalimantan. International REDD+ payments to the national government were expected to motivate performance in reducing emissions from deforestation at the subnational level, although the mechanisms for doing so have not yet been detailed in regulations (Irawan et al., 2019). In early 2019, Indonesia qualified for its first performance-based payment under the 2010 REDD+ agreement with the Government of Norway, thanks to modest emission reductions in 2017 and 2018 (Jong, 2019), and a USD56 million payment was announced in June 2020 (Government of Norway, 2020). In August 2020, the Board of the Green Climate Fund approved a REDD+ payment to Indonesia in the amount of USD103.8 million to recognize performance in 2014–2016 (Green Climate Fund, 2020).

Box 1. Green Development in East Kalimantan6.

The experience of JA in East Kalimantan illustrates the waxing and waning role of external incentives to motivate action at jurisdictional scale and the importance of agents to facilitate horizontal and vertical linkages.

East Kalimantan is Indonesia’s fourth largest province by area and the richest (after the special district of Jakarta) in terms of per capita income (Badan Pusat Statistik [BPS], n.d.). A leading producer of timber and plywood during Indonesia’s logging boom in the 1970s and 1980s, the province now derives the preponderance of its revenue from non-renewable resources, including oil and gas and especially coal. Conversion of forest to oil palm plantations emerged as a primary driver of forest loss over the past two decades. Berau is the third largest of seven districts in the province, covering 2.2 million hectares, with more than half of its area covered by concessions for logging, timber plantations, mining, and oil palm.

Jurisdictional approaches to controlling land-use change in East Kalimantan were initiated at both the provincial level and in the district of Berau in 2008. Motivated by the prospect of significant forest carbon finance in the wake of Indonesia’s hosting of the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties (COP) in Bali the previous year, each set up a REDD+ Working Group. Governor Awang Faroek Ishak subsequently launched a “Green East Kalimantan” (KalTim Hjau) program in 2009 and, in 2011, established a Provincial Council on Climate Change (Dewan Daerah Perubahan Iklim, or DDPI)—which evolved into a multistakeholder forum—to coordinate program activities. In parallel, the Berau Forest Carbon Program (BFCP) was launched in 2010.

Over the next 10 years, these interlinked JA initiatives served as the loci for promoting and coordinating myriad land-use interventions ranging from the level of individual villages and concessions to implementation of national and international programs. At the provincial level, commitments across sectors and stakeholder groups were later embodied in a Green Growth Compact encompassing 11 “prototype initiatives” related to forest conservation, social forestry, reducing carbon emissions, promoting sustainable agriculture, and institutional strengthening (Mongabay, 2016; Wahyuni et al., 2019).

The objectives of the Compact and specific innovations proven to be effective have been systematically mainstreamed into government policies, plans, and practice. For example, an initiative to identify and protect High Conservation Value forests within oil palm concessions was formalized in a 2018 provincial regulation on sustainable plantations. In 2019, East Kalimantan also formalized a provincial regulation on adaptation and mitigation of climate change, the first such provincial regulation in Indonesia to support the mainstreaming, planning, and implementation of emission reduction efforts (Yusuf, 2019). As another example, the Berau District Government is implementing a village-level planning and community forestry initiative called SIGAP (for Communities Inspiring Action for Change) in all 99 villages in the district, and provincial-level officials are exploring further replication (Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara [YKAN], 2018).

Linkages across levels have yielded benefits beyond scaling options. Although REDD+ was expected to be implemented at the district scale when the BFCP was initiated, subsequent changes in national law and policy shifted emphasis to the provincial scale. When East Kalimantan was selected as the pilot province for a results-based payment agreement with the FCPF Carbon Fund, the DDPI was able to build on the previous investment in developing the BFCP. It is notable that while forest carbon finance was the original stimulus for JA activities, and after 12 years finally appears to be within reach, the progress in East Kalimantan and Berau has been achieved in the absence of certain external reward.

Dozens of government agencies, donors, and development partners from among CSOs and the private sector have contributed to these achievements. Among these, TNC and its national partner Yayasan Konservasi Alam Nusantara have played a key role by facilitating linkages across sectors and levels and helping to maintain continuity through an ever-changing national policy environment and local elections. The embrace of the JA programs by a new governor and a new Berau District Head elected in 2018 indicate the robustness of the approach.

In the meantime, the prospect of results-based REDD+ finance to subnational jurisdictions arose for two provinces. After several years of preparation, by 2019 negotiations to conclude an Emissions Reduction Payment Agreement (ERPA) worth up to USD150 million between the province of East Kalimantan and the Forest Carbon Partnership Facility’s (FCPF) Carbon Fund (managed by the World Bank) had advanced to the stage of project appraisal (Government of East Kalimantan, 2019). In addition, the province of Jambi was selected for inclusion in the World Bank BioCarbon Fund’s Initiative for Sustainable Forest Landscapes (ISFL), accompanied by the establishment of a provincial-level task force (BioCarbon Fund, 2018). A prospective USD13.5 million grant in 2020 was designed to support activities that would generate emission reductions eligible for future performance-based payments.

However, a combination of the lack of certainty about the future availability of international REDD+ finance, a lack of national-level performance, and long delays in setting up the national infrastructure to receive and allocate REDD+ payments dampened enthusiasm. A lack of clarity over how any resulting financial rewards would be distributed has attenuated the incentives facing subnational jurisdictions. The financial mechanism (Badan Pengelola Dana Lingkungan Hidup or BPDLH) needed to intermediate the transfer of funds from international climate finance to domestic uses was established only in September 2019 after years of delay (Arumingtyas, 2019). The BPDLH’s REDD+ funds can be disbursed through results-based payments, grants, carbon-trade payments, or other financial instruments, and subnational governments are among potential beneficiaries, along with the national government, CSOs, private sector and research entities, and local communities (Mafira et al., 2020). However, how the new mechanism will use its flexibility to allocate funds remained unknown as of mid-2020, lending uncertainty as to the extent to which subnational jurisdictions would share in the proceeds from international payments.

Preferential Commodity Sourcing

In the case of commodity supply chain commitments, shifts in market demand were expected to reward jurisdictions exhibiting better performance in reducing deforestation with preferential sourcing and investment. Unilever and Marks & Spencer (in their roles as co-chairs of the Consumer Goods Forum) announced in 2015 a pledge to preferentially source from jurisdictions making progress toward reducing deforestation (Unilever, 2015). Various international initiatives designed to provide a framework for such preferential sourcing have since included pilots in Indonesia.

In 2015, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), a non-profit, membership-based certification body headquartered in Malaysia, endorsed a jurisdictional approach to certification of palm oil as sustainable, primarily as a way of including smallholders in systems that had been designed for industrial-scale plantations (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil [RSPO], 2015a). The initiatives supported by EII/INOBU in Central Kalimantan and IDH in South Sumatra, respectively, were among three pilots selected for developing a new RSPO standard for jurisdictional-scale certification (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil [RSPO], 2015b).7 The third pilot was the state of Sabah in Malaysia, where an ambitious target to achieve 100% certification for both palm oil and timber by 2025 had just been set (Bahar, 2018). Almost 4 years later, in mid-2019, the RSPO released for public comment a document on a jurisdictional approach to certification (Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil [RSPO], 2019).

In 2018, IDH launched a global initiative to establish “Verified Sourcing Areas” (VSA) as a strategy for linking global demand for sustainable commodities to specific producer jurisdictions (IDH, 2018a). While the first VSA pilot was established in Mato Grosso, Brazil, the second was in the district of Aceh Tamiang in the province of Aceh, Indonesia. In December 2019, a “Production, Protection, and Inclusion Compact” was signed by the head of the district along with representatives of other stakeholder groups. The Compact includes commitments and intermediate targets related to the legalization and certification of smallholder palm oil producers and protection of the adjacent Leuser Ecosystem. The external incentive for improved performance was implicit in the presence of three palm oil buyers—Unilever, Musim Mas, and PepsiCo—said to be “exploring investment opportunities” in the district (IDH, 2019).

How to assess and reward performance at jurisdictional scale, when transactions occur between buyers and specific producers, has not been obvious to corporate officials tasked with implementation of commitments to preferential sourcing. With the exception of Unilever’s memorandum of understanding (MOU) with 500 palm oil smallholders in the Central Kalimantan district of Kotawaringin Barat (which is not in fact implemented at jurisdictional scale), few market signals to reward performance—whether in terms of shifts in sourcing, increased investment, significant price premiums for certified products, or other favorable contract terms—have yet materialized. This challenge is one being taken on by companies participating in the Siak Pelalawan Landscape Program (SPLP) described in Box 2 on Green Siak.

Box 2. Siak Green Development Program.

Siak District in Riau province illustrates the key elements of the jurisdictional approach as promoted in Indonesia. About 57% of its 855,600-ha area is covered by carbon-rich peat up to 12 m deep, of which some 278,000 ha have been drained to make way for oil palm and fast-growing timber plantations. Palm oil produced by a mix of corporations and smallholders on 347,000 ha is processed in 17 mills across the district (Siak Government, 2019), while the district’s 16 timber plantation concessions supply the province’s large pulp and paper mills (Sedagho Siak and Siak District and Government, 2019).

Environmental degradation in the district has resulted in annual fires and enormous GHG emissions. Motivated in part by the especially severe fires experienced in 2015, Siak District Government announced in 2016 its commitment to be a “Green District” and to implement policies to improve environmental, social, and economic sustainability. A large part of the strategy focuses on improving management of peatlands to mitigate GHG emissions, fire, and subsidence while improving the productivity and sustainability of oil palm smallholders. The initiative was welcomed by local and national CSOs, which in 2017 established a forum called Sedagho Siak (Friends of Siak) to provide support (Elang, 2017).

In 2018, the Siak Government translated the green vision into a local regulation that determines land-use zoning. The local government further developed a road map in collaboration with Sedagho Siak that sets out clear targets and timelines, action plans, and the roles of various stakeholders to achieve them. The road map, issued in 2019, also states that concession holders are expected to implement NDPE policies in their operations (Sedagho Siak and Siak District and Government, 2019).

In 2018, a group of palm oil producers, traders, and buyers seeking to implement NDPE policies formed an alliance called Siak Pelalawan Landscape Programme (SPLP) (Proforest, 2018). Facilitated by Proforest and Daemeter, an alliance of companies including Cargill, Danone, Golden Agri-Resources, L’Oreal, Musim Mas, Neste, PepsiCo, and Unilever is lending private sector support to Siak and the neighboring district of Pelalawan, which had been chosen as a pilot for the National Sustainable Palm Oil Actin Plan (Daemeter, 2019). Coordinating with the local governments and Sedagho Siak, SPLP aims to transition large parts of both districts toward producing deforestation- and exploitation-free palm oil.

The Siak Government is also working with CSOs to address needed alignment between national and local priorities. For example, 10,000 ha of mostly deep peat that had been excised from a concession and returned by a private company to government control for protection was allocated by the central government for development under the national agrarian reform program (Halloriau, 2020). Thanks to the quick coordination by local and national CSO networks in support of the district government, 4,000 ha of the area is now under communal management. Communities in the area are trialing various types of paludiculture (a type of farming system that does not require drainage) as well as restoration. These and other JA activities are being supported by Winrock International and local CSO Elang in collaboration with the district government.

A founding member of the Sustainable Districts Association (Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari [LTKL]), Siak continues to provide examples of how JA can be implemented with the continuous support of other stakeholders.

Green Investment

Preferential access to investment was expected to constitute an additional element of the global value proposition for local leaders to pursue green development. For example, in 2017, with support from the Norwegian International Climate and Forest Initiative (NICFI) and Unilever, the IDH Sustainable Trade Initiative set up &Green, a global investment fund that provides capital for the intensification of agricultural commodity production and other business models thought to reduce deforestation. &Green’s link to JA is through a jurisdictional eligibility approach, articulated on the fund’s website as follows: “Limiting &Green investments to jurisdictions with progressive forest and/or peat protection strategies ensures reinforcement of public policy signals through private sector investment.” The Indonesian jurisdictions of Jambi, South Sumatra, and West Kalimantan were approved by the fund’s Advisory Board as meeting the eligibility criteria. &Green financed a sustainable rubber project in Jambi in 2019 (The and Green Fund, n.d.) and announced its investment in a palm oil project in Kalimantan (Green, 2020). A mid-term evaluation of the &Green fund suggests that the initiative has experienced difficulties in attracting additional capital to the fund and that investee companies have had trouble meeting its high standards (Steward Redqueen, 2020). The evaluation report did not address the effectiveness of the jurisdictional eligibility criteria in motivating improvements in public policy.

In the meantime, CSOs working on JA in Indonesia have found that attracting such investment is of particular interest to local leaders and have intensified their efforts to link JA activities to a regional competitiveness narrative. The Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari (LTKL) (described in Box 3) developed a series of “Masterclass” training programs to assist member districts in attracting green investment (Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari [LTKL], 2018a). The first series, held from December 2018 to June 2019 in collaboration with Indonesia’s District Governments Association (Asosiasi Pemerintah Kabupaten Seluruh Indonesia or APKASI), the Tropical Forest Alliance (TFA), and the Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP) focused on investment to transition production of strategic commodities, such as palm oil, rubber, cocoa, coffee, spices, coconut, and non-timber forest products, toward sustainability. Local governments were encouraged to develop an investment portfolio that was presented to potential investors at the end of the program. The Masterclass program was picked by Indonesia’s Investment Coordinating Board, which collaborated with LTKL in 2019 for similar trainings involving 29 provincial governments.

Box 3. Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari [LTKL]: Indonesia’s Sustainable Districts Association.

In a conversation among a handful of Indonesian district heads and CSO leaders in the margins of an RSPO meeting in late 2016, the idea of a platform to support districts to advance and collaborate on their sustainability agendas was born. The idea reflected recognition of the need for government leadership of the sustainability agenda (learning lessons from the IPOP experience), the need to support district heads’ stated commitments to sustainability with practical technical assistance, and the potential of collaborative action to inject district-level interests into national and international policy arenas.

Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari (Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari [LTKL], n.d.)—rendered in English as the Sustainable Districts Association—was formally established in July 2017 by eight districts from six provinces in cooperation with APKASI, the national association of district-level governments. It has since grown to 12 districts in eight provinces. LTKL is governed by a general assembly of its member districts, managed by an executive committee composed of eight district heads, and supported by a secretariat based in Jakarta. The work of the secretariat is amplified by a network of more than a dozen partner organizations, including Jakarta-based CSOs that can offer support services such as strategic planning assistance, and local alliances such as Sedagho Siak and Sahabat Muba. Priorities selected by the membership include social forestry and agrarian reform, clean energy and electrification, control of forest and peatland fires, sustainable commodity production, conservation and restoration, waste management, and disaster prevention and response.

Since its founding, LTKL has emerged as an active source of technical assistance for member districts, a convener at the national level, and a participant in shaping relevant international initiatives. Its focus has been on building both the business case and the political case for transitioning to a more sustainable development path, helping to connect district-level stakeholders to national and international sources of finance, markets, and recognition. Member districts have evidenced their sense of ownership of LTKL’s agenda by agreeing to pay a membership fee and spend their budgets on LTKL-related activities, such as the Festival Kabupaten Lestari and attendance in Masterclass trainings.

However, actual green investment transactions have been slow to materialize at scale, with or without an explicit link to incentives for jurisdictional-scale performance. For example, the Tropical Landscapes Finance Facility—launched in 2016 with the support of the United Nations Environment Programme, ICRAF, ADM Capital, and BNP Paribas with the objective of unlocking private finance for sustainable land use—had concluded only one project by early 2020. The investment is in the form of a corporate sustainability bond linked to the same rubber project financed by &Green mentioned above (TLFF, n.d.).

Ecological Fiscal Transfers

Indonesia has also been the locus of significant efforts to advance the case for using domestic fiscal policy to reward subnational jurisdictions for maintenance of forest cover. Current fiscal policies incentivize governments across levels to support land-use change, so shifts toward low-emissions development would entail opportunity costs to local government (Irawan et al., 2013). The Climate Policy Initiative published studies analyzing the potential of fiscal policy reforms to incentivize more sustainable land-use practices at the regional level both in general (Falconer et al., 2015) and for the specific case of Berau District in East Kalimantan (Mafira et al., 2019).

At the national level, proposals for “ecological fiscal transfers” follow a model pioneered in India, in which forest cover is included as a variable in the formula that governs the distribution of revenues to states (Busch and Mukherjee, 2017). In 2017, the Research Center for Climate Change at the University of Indonesia, with support from the Government of Germany, organized a study tour to India for senior officials from the Indonesian government, including members of the house of representatives, district heads and deputy heads, and officials from the ministries of finance, planning, and environment and forestry (Mumbunan, 2018). In September 2018, representatives of 13 forest-rich district governments signed the “Cikini Communique” requesting a national policy to include forest cover in the formula to determine the districts’ budget allocations (Komunike Cikini, 2018).

Other proposals focus on incentivizing forest protection through revenue allocation between subnational levels of government. In 2018, The Asia Foundation presented a proposal in several venues for “Ecological-based Provincial Fiscal Transfer for Forest Conservation” (or TAPE), in which provinces would use budgetary discretion to reward environmental performance by districts and municipalities (Pwyp Indonesia, 2018).

However, despite extensive efforts by civil society groups to make the case for using domestic fiscal policy to reward sustainability performance, and interest expressed by subnational elected leaders, the proposals described above have not yet been embraced by the Ministry of Finance and other relevant ministries. As a result, many subnational leaders continue to see forest protection as an uncompensated fiscal disability.

Reputational Benefits

Early in the development of JA in Indonesia, proponents sought to reward provincial and district leaders with international recognition for their commitments to sustainability. For example, South Sumatra Governor Alex Noerdin launched his Green Growth Action Plan at an event organized by IDH at the UNFCCC COP in Paris in 2015 and met with actor Leonardo DiCaprio (IDH, 2015); East Kalimantan Governor Awang Faroek Ishak spoke about the Green Growth Compact at an event organized by TNC at an event organized by TNC at the UNFCCC COP in Marrakech in 2016 (PR Berau, 2016); and West Papua Governor Dominggus Mandacan announced a commitment to protect the forests of his province at an event in Oslo in 2018 (Tempo, 2018). District-level leadership has been highlighted through the Musi Banyuasin District Head’s participation in the 2018 European Palm Oil Forum in Madrid (Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari [LTKL], 2019b) and the Siak District Head’s participation in the TFA annual meeting in Bogota in 2019.

Such events have served as mechanisms to elicit public commitments to sustainability and have provided incentives in the form of favorable local media attention and the perquisites associated with international travel. However, skepticism over the degree to which such commitments can be sustained in the absence of material incentives for performance is justified. Consistent with JA experience globally (Boyd et al., 2018), commitments by subnational leaders to pursue low-carbon development are not always followed immediately by actions that alter the trajectory of land-use change.

Over time, CSO proponents of JA in Indonesia have come to appreciate the importance of national-level recognition for local leadership (Aurora and Seymour, 2019). Such recognition can come in the form of acknowledgment by peer groups, media attention, and the prestigious Nirwasita Tantra awards given by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry to recognize “green leadership” at the subnational level (JPNN, 2019). In 2020, the Regional Autonomy Watch (Komite Pemantauan Pelaksanaan Otonomi Daerah or KPPOD) began developing a Regional Competitiveness Award based on key indicators of sustainability at jurisdictional scale.

Initiatives Focused on Facilitating Activities Within Jurisdictions

By far the preponderance of effort on JA in Indonesia to date has focused on facilitating activities within jurisdictions. From a handful of pilot initiatives underway in 2014, JA rapidly spread to additional districts and provinces beyond those mentioned above. For example, IDH expanded its efforts to develop Green Growth Plans to five provinces in addition to South Sumatra. At the district level, Winrock International and Elang have promoted JA in Siak in Riau, the Conservation Strategy Fund and WWF in Sintang, and Aidenvironment in Ketapang, both in West Kalimantan. These three districts were chosen as JA pilots by CLUA and supported by its member foundations.

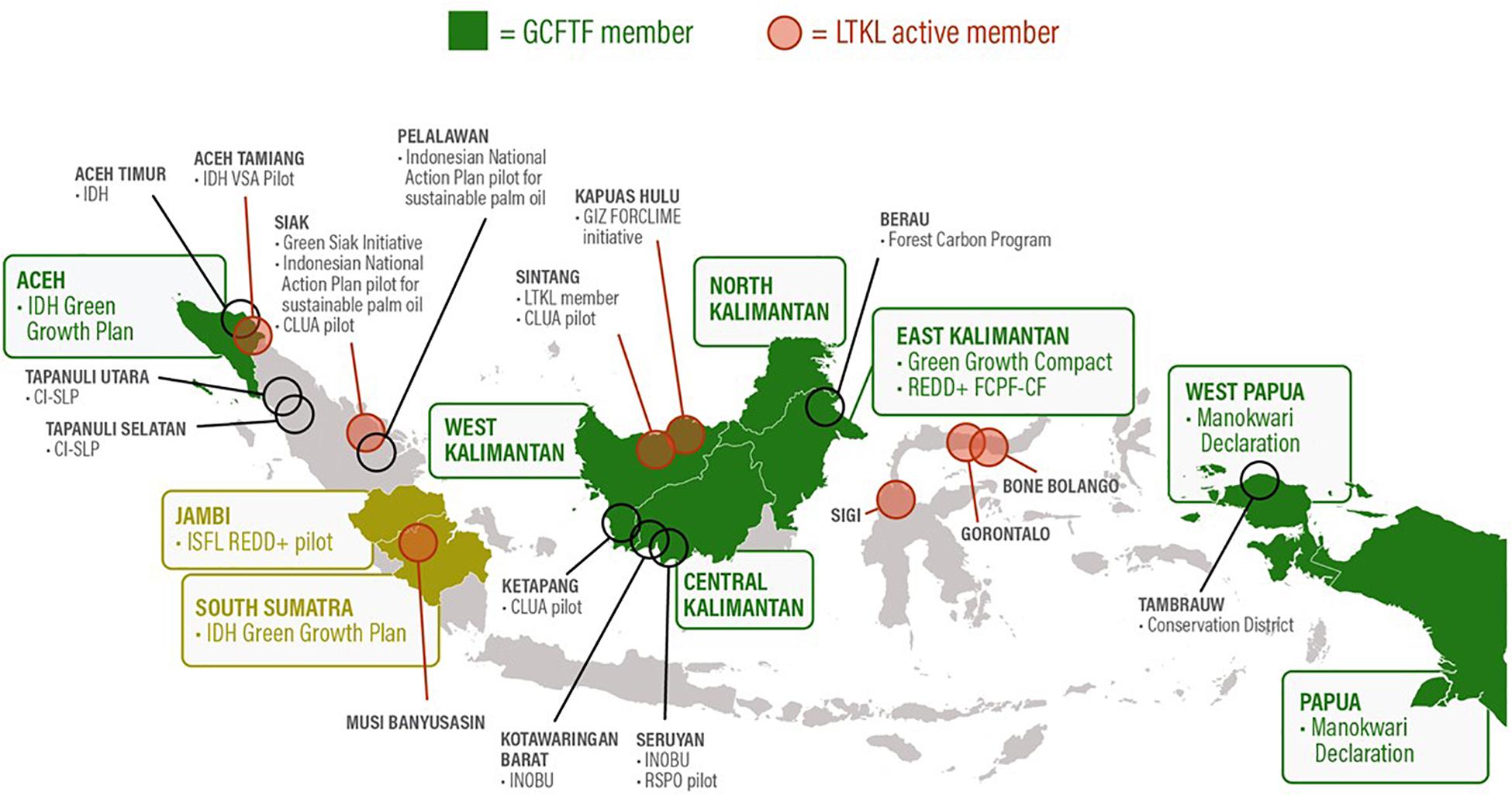

Geographically, significant attention from domestic and international NGOs and donors has been trained on the provinces of Papua and West Papua in Indonesia’s far east, where the largest expanses of intact forests remain. The governors of the two provinces in 2018 signed the Manokwari Declaration, which articulated a vision and specific steps toward sustainable land use, including a commitment to conserve 70% of the jurisdictions as forest as well as to recognize indigenous rights (IDH, 2018b). The Declaration was preceded by the declaration of Tambrauw District in West Papua as a “Conservation District” in Fatem et al. (2018). Figure 4 illustrates the number and geographic spread of provinces and districts with some level of JA activity underway as of early 2020.

The activities supported by JA proponents in individual jurisdictions have tended to include some combination of:

• Developing a jurisdictional-scale vision for green development endorsed by the governor or district head and elaborating associated targets and roadmaps;

• Convening multistakeholder forums to support implementation;

• Supporting specific programmatic activities such as smallholder legalization and certification, social forestry, or forest protection, and compiling associated data necessary for implementation;

• Integrating elements of the plan into regular planning and budgeting processes and promulgating supportive local regulations; and

• Developing systems for monitoring and reporting on progress.

A group of more than 20 CSOs in Indonesia’s emerging community of practice on JA agreed on these as key elements for effectiveness (Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari [LTKL], 2019c). The following sections provide illustrative examples of progress on these elements and associated challenges.

Articulating Jurisdictional-Scale Visions, Targets, and Road Maps

A first step in several JA initiatives has been to articulate a high-level vision for sustainable development in the jurisdiction endorsed by its elected leader. As described in Box 1, the governor’s signature Green Growth Compact rolled out over the course of 2016–2017 provided the framework for a transition to sustainability in East Kalimantan. The Green Siak Initiative described in Box 2 was launched by the district head in 2017 and a Road Map issued in 2019. The Road Map articulated objectives including balancing conservation and economic growth and reducing damage to peatlands and water catchment areas (Sedagho Siak and Siak District and Government, 2019). Without such initial political-level commitment, JA proponents have found it difficult to gain traction. For example, despite concerted efforts by various CSOs to develop a JA initiative in the district of Ketapang, little progress has been possible in the absence of leadership from the district government.

Sustaining momentum in the face of political turnover has proven a challenge. For example, when Central Kalimantan Governor Teras Narang left office in 2015, efforts to follow up on the Road Map to Low Emissions Development stalled. However, election results can also reinforce momentum for JA. In 2018, the Siak district head, Syamsuar, was elected Governor of Riau, with the prospect that he could extend his vision for green development province-wide, and in January 2020, the province officially became a pilot for the implementation of the national government’s low-carbon development effort (Tari, 2020). These developments are especially significant in light of the fact that two previous governors of the province had been successfully prosecuted and jailed for corruption related to the illegal allocation of forest permits. The political success of Syamsuar has likely informed the decision of his successor as district head, Alfedri, to support continuation of the Green Siak Initiative and leadership in LTKL.

Convening Multistakeholder Forums

Another common element of JA initiatives in Indonesia has been the establishment of supportive multistakeholder bodies. In East Kalimantan, a provincial-level forum on climate change, appointed by the governor and led by a respected senior academic, has served to coordinate various elements of the provincial green growth strategy. In Sintang, Pelalawan, and South Tapanuli Districts, Indonesian Sustainable Palm Oil Forums (FoKSBI) involving representatives from government agencies, the private sector, and civil society were formed in accordance with the National Sustainable Palm Oil Action Plan. Subsequently, with support from Conservation International, the Coalition for Sustainable Livelihoods was established in 2018 to coordinate government, private sector, and CSO activities focused on sustainable smallholder commodity production in Aceh and North Sumatra (Conservation International, n.d.). In several districts, separate platforms for CSOs to support jurisdictional-scale actions have been established, including Sahabat Muba (“Friends of Muba”) in Musi Bayuasin, Sedagho Siak (“Friends of Siak”) in Siak, and FKMS (Civil Society Communication Forum) in Sintang (Lingkar Temu Kabupaten Lestari [LTKL], 2019a). As described in Box 2, the Siak Pelalawan Landscape Programme is a collaboration among palm oil producer and buyer companies supporting the shift to sustainable production in both districts.

An obstacle to the effective functioning of several such forums has been the lack of trust between various stakeholder groups, often the legacy of past conflicts over natural resources. For example, in Riau province, many CSOs, academics, and even government officials bear an animus against the large pulp and paper sector companies that were responsible for large-scale forest and peatland destruction and associated social conflicts until relatively recently. Despite their stated desire to contribute to JA initiatives in the province, those companies were not initially welcomed into the multistakeholder processes now underway.

In West Papua and Papua, cooperation among civil society groups has been hindered by differences in strategic approaches. Although the Manokwari Declaration commits to protecting both forests and indigenous rights, conservation groups have tended to prioritize seeking official protection for remaining forest areas to safeguard them from conversion to commercial-scale plantations. Rights-oriented groups have viewed those efforts with suspicion, insisting that recognition of indigenous rights to those areas must be secured first. More broadly, this lack of trust among different elements of civil society may have contributed to the limited integration of the indigenous rights agenda into the practice of JA in Indonesia.

Supporting Specific Programmatic Activities

Most JA initiatives provide support to specific project-scale activities as a way of advancing jurisdictional-level objectives. For example, as described in Box 1, East Kalimantan’s green growth strategy has been supported by almost a dozen “prototype initiatives” with support from TNC. One such initiative called SIGAP has facilitated village-level planning and community forest management in Berau district, including assistance to communities in securing tenure through national social forestry programs. Another program element works with the provincial estate crops agency and private companies to identify and protect High Conservation Value (HCV) forests within licensed concession areas.

The East Kalimantan initiative is an exception to a more general tendency on the part of both local leaders and partners external to the jurisdictions, which is to emphasize development objectives and neglect conservation goals in prioritizing JA-related activities. This tendency is an understandable artifact of the need to identify entry points meaningful to stakeholders in the jurisdictions, as well as of the lack of external rewards for conservation.

Many of the early JA initiatives with an entry point in the palm oil sector focused on engagement with smallholder farmers to legalize, certify, and intensify production on already-cleared land. This strategy responded to a political discourse—one that reached a crescendo during the short life of IPOP—claiming that smallholders would be hurt by the implementation of deforestation-free commodity supply chain commitments. Often the strategy was justified as way of reducing pressure to clear more forests, despite the lack of supporting evidence that such efforts would be effective.

For example, the proponents of the EII/INOBU initiative to promote sustainable palm oil production in Seruyan, Central Kalimantan, focused on the mapping and legalization of oil palm smallholders in the central part of the district where forests had already been cleared but did not address ongoing illegal logging taking place in the northern part of the district. Further, the linkage between the MOU with Unilever—which agreed to source certified sustainable palm oil from 500 smallholders in Kotawaringan Barat—and the goal of reducing deforestation at the scale of the jurisdiction was unclear. Nevertheless, the program had significant direct and indirect outcomes. Thanks to better data and mapping, thousands of smallholders in the two districts have received the registration letters that are a first step toward legalization. The online database developed through the program called SIPKEBUN was adopted and is now managed by the national Ministry of Agriculture (InfoSAWIT, 2016).

Promulgating Supportive Regulations and Plans

Increasingly, proponents of JA in Indonesia have focused on mainstreaming their objectives into the standard planning and budgeting documents at jurisdictional scale, as well as into local regulations. For example, with the assistance of the Conservation Strategy Fund and CSOs in the district, the Sintang District Head issued a decree in 2019 establishing a Sustainable Sintang Regional Action Plan 2019–2021, which in turn will be integrated into the next revisions of the official medium-term plan (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah or RJPMD) and spatial plan. Similarly, the Green District Siak Road Map, prepared with input from CSOs, based on a decree from the district head, will inform the RPJMD and spatial plan. At the provincial level, the South Sumatra government has created a road map based on a decree from the governor that will be integrated into RPJMD and spatial plans. The work to protect HCV forests within concessions in East Kalimantan is supported by Regional Regulation on Sustainable Plantations.

However, a common refrain at meetings of JA proponents to exchange experience relates to the lack of spatial data at the level of subnational jurisdictions to support planning and monitoring. Slow progress in realizing the objectives of the national One Map Policy (the Geoportal for which was finally launched in late 2018) has meant that critical data—such as data on areas covered by concession licenses issued by various agencies—has been unavailable to local authorities or to the public. Further, the recent creation of new provinces and districts through the process of pemekaran has meant that many local governments are quite young, with little capacity for planning, budgeting, and fulfilling the many bureaucratic demands placed on them by higher levels of government. Even in more mature jurisdictions, JA proponents have been challenged by the lack of understanding and capacity—and sometimes interest—on the part of lower level bureaucrats to translate high-level political visions into operational plans. As a result, many JA proponents have invested significant time and resources in assisting government officials to undertake these processes. The LTKL secretariat, for example, has enlisted its network of partner organizations at the national level to provide member districts with support and training in activities such as strategic planning.

Developing Monitoring and Reporting Systems

Many JA initiatives in Indonesia have invested in developing systems to monitor and report progress. Often designed to serve multiple purposes, such systems provide feedback to multistakeholder forums within the jurisdiction to inform adaptive management of the initiative, to provide data for standard government reporting requirements, and to qualify for external incentives. For example, with support from the Earthworm Foundation, the Aceh Tamiang District Government is working closely with CSOs, companies, smallholders, and communities to monitor data on biodiversity management, respect for workers’ rights, and palm oil plantation replanting (Earthworm, n.d.).

At the provincial level, members of the GCFTF, including Aceh, West Kalimantan, East Kalimantan, and North Kalimantan, have collaborated with CIFOR and EII to assess the progress of their sustainability initiatives. This assessment includes evaluating goals and commitments toward sustainable development, monitoring and reporting systems, innovative policies and initiatives, land-use policies, multistakeholder participation in governance, emission-reduction strategies, and the management of drivers of deforestation and degradation to achieve low-emission and sustainable development (Stickler et al., 2018).

However, jurisdictions are challenged by the bewildering variety of indicator frameworks under development to assess jurisdictional sustainability for the purposes of determining preferential access to commodity markets. As a service to its members, the LTKL Secretariat is facilitating a process to develop indicators that are meaningful to both local and international stakeholders, as well as feasible for districts to report on in light of the capacity and data constraints mentioned above. LTKL has summarized the draft indicators for jurisdictional sustainability from various frameworks, including RSPO Principles & Criteria, Terpercaya (developed by the European Forestry Institute and INOBU), the Verified Sourcing Area concept (developed by IDH), and the Sustainable Landscape Rating Tool (developed by the Climate Community and Biodiversity Alliance). These in turn have been synthesized into a voluntary district reporting framework called the Regional Competitiveness Framework (Kerangka Daya Saing Daerah or KDSD). The draft KDSD was endorsed by member districts in 2019, and a trial to collect baseline data in Siak, Sintang, and Gorontalo districts was ongoing in early 2020. Preliminary findings suggest that an average of only 30% of the data needed to satisfy the indicator frameworks is available at the district level.

Initiatives Focused on Facilitating Connections Across Jurisdictions and Levels

As described in the previous section, significant effort on the part of JA proponents has been invested in facilitating activities within subnational jurisdictions. Roles taken on by local affiliates of international organizations such as TNC, IDH, Winrock International, and Conservation International, and/or local CSO coalitions such as Sedagho Siak and FKMS in Sintang have included supporting local governments to articulate their green visions into planning documents, facilitating multistakeholder forums, and coordinating CSO and private sector programs on the ground. However, in addition to the facilitation roles played within individual jurisdictions, JA proponents have identified a need for complementary facilitation of horizontal linkages across jurisdictions and vertical linkages with national and international policy arenas.

Facilitating Horizontal Connections Across Jurisdictions

As mentioned above, the participation of seven Indonesian provinces in the GCFTF was one of the antecedents of JA in Indonesia linked to REDD+. As a platform linking leaders from 38 states and provinces around the world, the GCFTF has served as a source of knowledge and inspiration for several JA initiatives in the country. Indonesian governors and/or their senior staff have participated in annual meetings of the GCFTF hosted by peer jurisdictions in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia, as well as in GCFTF-organized side events at UNFCCC COPs and other international gatherings. Seven Indonesian provinces signed on to the Rio Branco Declaration, a pledge organized by the GCFTF in 2014 committing signatories to reducing deforestation by 80% by 2020 in return for commensurate financial support from the international community. While the Declaration did not prompt significant additional REDD+ finance to jurisdictions in Indonesia or elsewhere, signatory jurisdictions in Indonesia were eligible for and received investment planning grants funded by Norway and administered by the United Nations Development Programme (Stickler et al., 2020). Hosting the GCFTF annual meeting in 2017 in East Kalimantan gave Governor Awang Faroek Ishak an opportunity to showcase the province’s Green Growth Compact to the international community and solicit commitments of support (Komalasari et al., 2018).