Peer effects of enterprise green financing behavior: Evidence from China

- School of Economics and Management, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, China

Green finance is critical for adjusting the industrial structure and promoting sustainable economic development; therefore, it is important to understand enterprise green investment and financing behavior. This study aims to investigate the peer effects of enterprise green financing behavior. Based on theoretical analysis, this study selected data from Chinese A-share listed companies from 2011 to 2020 as the research sample. In this study, the fixed effects model was used to examine the peer effects of enterprise green financing. Meanwhile, a moderating effect model was employed to explore the function of the economic policy uncertainty and corporate social responsibility commitment on peer effects of enterprise green financing. The results show that the enterprise’s green financing behavior increases significantly with its peer companies’ (i.e., other companies in the same industry or the same region) green financing behavior, and responds to peer companies’ characteristics in the same industry, indicating peer effects on green financing behavior. The peer effects of enterprise green financing are stronger when the economic policy uncertainty is higher, suggesting that the green financing behavior of peer companies reduces external uncertainty by providing comprehensive and useful information, thus enhancing the enterprise’s information environment and enabling it to make better green financing decisions. Moreover, peer effects are more pronounced when corporate social responsibility commitment is higher, indicating that peer companies’ higher performance in social responsibility can improve their information transparency and build good reputation, increasing the enterprise’s disclosure and reputation costs in the capital market. Therefore, our findings highlight the importance of peer effects in enterprise green financing behavior. To enhance the enterprises’ green financing behavior and promote green finance development, the government should focus on the industrial and regional situation to conduct green finance and promote the overall green financing behavior of enterprises by establishing typical enterprises or pilot cities.

1 Introduction

China’s economy has developed rapidly since its reform and opening up (Fang et al., 2022). However, this extensive development model has also resulted in the excessive consumption of natural resources and environmental destruction (Gu et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2022), non-conducive to long-term high-quality economic and social development (Cao and Wang, 2017). Therefore, combining finance and sustainable development concepts to build a green financial system has become inevitable for transforming China’s economic development mode and ensuring sustainable development (Zhang et al., 2022). In recent years, China’s central and local governments have adopted many policies and measures to solve environmental problems (Li et al., 2021). In 2016, seven departments,1 including the People’s Bank of China, issued Guidance on Building a Green Financial System which pointed out that green finance is an economic activity that supports environmental improvement, and helps cope with climate change and save resources. It has become crucial for the development of green economy and is the key to adjusting industrial structure and promoting high-quality economic development (Wu, 2022).

China has changed its economic development mode from high-speed development to high-quality development recently (Wu et al., 2021). Capital is the blood of economic operation, so environmental governance cannot be separated from financial support (Yu, 2021). The report of the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China pointed out that the country should build a market-oriented green technological innovation system and develop green finance. In March 2021, the National People’s Congress highlighted that in the “14th Five-Year Plan” we should adhere to the concept of clear water and green mountains as gold and silver mountains and stressed promotion of green finance development and support of green technology innovation (Wang and Zhou, 2022). Green finance can guide funds from polluting enterprises to green enterprises by optimizing allocation of financial resources to promote the optimization and upgradation of green industrial structures. Therefore, it can control pollution, improve environmental quality, and promote sustainable economic development. (Gu et al., 2021). The green financial system mainly supports green economic transition through green credit, green bonds, the green stock index and related products, green development funds, green insurance, carbon financial and other financial instruments, and related policies (Weng et al., 2015). Simultaneously, the bank-led characteristic of China’s financial system determines that green credit is the most important component of green finance. (Wu, 2022). China has actively developed green finance in recent years to guide enterprises’ green investment and stimulate green innovation vitality, forming a green financing system with green credit as its largest component (Tan et al., 2022). Further development of green finance requires the government, banks, enterprises, investors, and consumers to play a synergistic role (Herman and Shenk, 2021). The government provides green financial policy support to promote the development of green finance, (Peng and Zheng, 2021), while banks develop and improve their credit policies (Lioui and Sharma, 2012; Kim et al., 2014). In addition, as the main body of energy conservation and emission reduction, enterprises’ improvement in green financing can promote green technology innovation (Li Z et al., 2018) and reduce pollution emissions (Fan et al., 2021), which is of great significance to the development of green finance and promotion of high-quality economic development.

Existing studies on green finance focus on its connotation (Chen et al., 2019), green financial products (Li Z. S et al., 2018; Flammer, 2021; Amighini et al., 2022), the green financial behavior of different subjects (Lioui and Sharma, 2012; Kim et al., 2014) and the impact of green finance on enterprises, the economy, and the environment (Li Z et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020; Flammer, 2021). On the other hand, existing studies show that peer effects affect enterprises’ investment and financing decisions (Foucault and Fresard, 2014; Leary and Roberts, 2014; Kaustia and Rantala, 2015; Bustamante and Fresard, 2021), merger and acquisition decision-making (Gu et al., 2022) and corporate governance (Adhikari and Agrawal, 2018; Yang et al., 2020), etc. Peer effects can help enterprises make important decisions when it is difficult for them to obtain useful information efficiently and at a low cost (Kaustia and Rantala, 2015). In addition to other internal and external factors, peer companies’ financing behavior is also an important factor affecting enterprise financing decisions (Devenow and Welch, 1996; Lieberman and Asaba, 2006; Leary and Roberts, 2014). In the case of the incomplete development of green finance in China, enterprise green financing behavior is likely to be affected by the green financing behavior of peer companies. However, few studies have analyzed enterprise green financing behavior from the perspective of peer effects. Therefore, this study explores whether peer companies’ green financing behavior affects enterprise green financing from the perspective of peer effects.

Based on the data of Chinese A-share listed companies from 2011 to 2020, this study empirically tested the peer effects of enterprise green financing from the two dimensions of industry and region. The study found that peer effects exist in the green financing of enterprises in the same industry (same region). That is, peer companies’ green financing behavior has a positive impact on enterprise green financing, and the characteristics of peer companies in the same industry affect enterprise green financing significantly. Furthermore, both economic policy uncertainty and corporate social responsibility commitment have positive moderating effects on the peer effects of enterprise green financing behavior.

The main contributions of this study are as follows. First, this study tests peer effects in enterprise green financing behavior, which enriches the empirical studies related to green finance and peer effects. Second, it explores the function of the economic policy uncertainty and corporate social responsibility commitment on peer effects of enterprise green financing, thus providing empirical evidence for the influence mechanism of peer effects in enterprise green financing. Third, existing studies often assume that enterprises make decisions independently of the influence of other enterprises’ behavior. However, this study shows that enterprise green financing behavior is not only affected by the external policy environment and internal factors but also by the peer companies’ green financing behavior, which provides practical value for the development of green finance in the future.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and proposes the hypothesis. Section 3 sets up the model and variables, and Section 4 presents the empirical results and analysis of peer effects in enterprise green financing. Section 5 presents an analysis of the influence mechanism of the peer effects. Finally, Section 6 summarizes the study and proposes policy suggestions.

2 Literature review and research hypothesis

2.1 Literature review

Early research on green finance focused on the role of financial institutions in environmental protection and sustainable development (White, 1996; Jeucken and Bouma, 1999). Wang (2000) introduced the concept of green finance to China and explained its necessity and basic development ideas. Subsequently, many studies explained its concept and connotation (Chen et al., 2019) and discussed the ways to construct a green financial system in future (Ma, 2016). Green finance contributes to the macroeconomy (Liu et al., 2019; Ren et al., 2020; Zhou et al., 2020), industrial structure (Guo et al., 2015; Du et al., 2017), and enterprises (Li Z. S et al., 2018; Flammer, 2021).

In 2016, seven departments, including the People’s Bank of China, issued Guidance on Building a Green Financial System, which specified that the green finance system includes green credit, green bonds, green stock index and related products, green development fund, green insurance, carbon finance, and so on. Among them, green credit, as a major component of green finance, contributes to the technological innovation of enterprises (Li Z et al., 2018; Yu, 2021) as well as investment and financing decisions (Su and Lian, 2018; Wang et al., 2021). Moreover, green credit of commercial banks is main source of funds required for the development of the green industry, so banks need to strengthen green credit management (Jiang and Xu, 2016; Ding et al., 2020) to cooperate with the government and green enterprises and jointly build a green financial system. At the same time, green bonds, an important part of green finance, started late but grew quickly. Because their green features can help build good reputation for enterprises and be supported by policies (Qi and Liu, 2021), green bonds have the characteristics of a high rating, low risk, and strong liquidity (Jin and Han, 2016). Additionally, existing studies have analyzed the green stock market (Flammer, 2021), green fund (Amighini et al., 2022), green insurance, and so on, to deepen the understanding on the construction of green financial systems.

The main bodies of green finance include banks, governments, enterprises, consumers, investors, etc. Further development of green finance requires that different main bodies play a synergistic role. In addition to the government’s continuous improvement of green finance policies and systems, banks have developed green finance services (Lioui and Sharma, 2012; Kim et al., 2014). As the main body of energy conservation and emission reduction, enterprises have to establish environmental awareness and improve green financing levels to promote green technology innovation (Li Z. S et al., 2018) and reduce pollution emissions (Fan et al., 2021). This is significant for the development of green finance and promotion of high-quality economic development.

There is no unified definition of green financing in domestic academic circles at present; its basic connotation is that enterprises take environmental protection as guidance, and conduct financing activities through financial instruments, such as green credit, green stocks, green bonds, green funds, and green insurance by using funds for energy conservation and emission reduction. This is done to promote sustainable development of enterprises, environmental protection, and high-quality economic development. On the one hand, enterprise green financing is influenced by government policy support and bank credit (Lioui and Sharma, 2012; Kim et al., 2014); on the other hand, it may be influenced by the green financing behavior of companies in the same industry or region.

Studies on peer effects started in education and sociology (Sacerdote, 2001; Glaeser et al., 2003) and have been widely studied at the enterprise level (Faulkender and Yang, 2013; Leary and Roberts, 2014; Kaustia and Rantala, 2015). Peer effects refer mainly to the influence in decision-making on economic agents by other agents in the same group. Such influence may be caused by similar resource allocation, market competition, and business risks faced by enterprises in the same industry or by similar economic development levels, policy systems, and market environments in the same region (Wang and Chu, 2022).

Peer effects affect all aspects of enterprise decision-making. Enterprise investment decisions are affected by companies in the same industry, but the changes in the two are not completely consistent (Foucault and Fresard, 2014; Bustamante and Fresard, 2021). Simultaneously, economic policy uncertainty enhances the peer effects of enterprise investment because managers tend to be consistent with their peers to reduce the impact of asymmetric information and external risks (Hu, 2022). Peer effects in merger and acquisition decision-making (Gu et al., 2022) are important factors affecting the goodwill of GEM companies’ merger and acquisition (Fu et al., 2015). In terms of corporate financing decisions, peer effects exist in the corporate capital structure (Leary and Roberts, 2014; Kaustia and Rantala, 2015; Lian et al., 2020). As for corporate governance, peer effects exist in the equity pledge of controlling shareholders, which aggravate the risk of stock price crash (Yang et al., 2020). Moreover, the increase or decrease in the dividend distribution of listed companies has peer effects (Adhikari and Agrawal, 2018), and the distribution of cash dividends by enterprises can be affected by peer companies in the social network (Feng and Wang, 2021). For executive compensation, enterprises will imitate large-scale high-profit companies in the same industry (Bizjak et al., 2008). In particular, peer companies positively affect the compensation of senior executives in the same industry and region (Zhao, 2016).

In terms of the impact on the enterprise and society, peer effects generate both positive and negative effects. On the one hand, peer effects can promote enterprise R&D investment (Xiong et al., 2016), green technology innovation (Wang and Chu, 2022), corporate social responsibility (Liu and Wu, 2016; Cao et al., 2019) and corporate donations (Wang and Cao, 2017). It is, therefore, conducive to the stable development of enterprises. On the other hand, peer effects exist in the financialization of enterprises (Zhang et al., 2021), excessive enterprise debt (Li Z et al., 2018), and violations (Lu and Chang, 2018), which aggravate the risks in enterprise and industry development.

2.2 Research hypothesis

According to existing studies, peer effects exist in various situations and reflect the average behavior of a group that affects behaviors of the individuals constituting the group (Manski, 1993). Graham and Harvey (2001) found through a survey of the chief financial officers (CFO) of American listed companies that most of them would refer to other enterprises’ decisions when making their financing decisions. Although most studies on enterprise financial policies assume that enterprise decision-making is independent of peer behavior or characteristics; in fact, enterprise financing is affected by peer financing behavior that is even more important than the influence of other factors (Devenow and Welch, 1996; Lieberman and Asaba, 2006; Leary and Roberts, 2014). Due to information asymmetry in the market, when it is difficult to obtain useful information efficiently at a lower cost, many listed companies will refer to their peer companies’ behavior to make important strategic decisions (Kaustia and Rantala, 2015). Therefore, when enterprises conduct green financing, they are affected by the green financing behavior companies in the same industry or in the same region, and the peer companies’ green financing behavior may promote the green financing behavior of enterprises themselves.

There are two potential influence mechanisms underlying peer effects on enterprise green financing. First, when faced with uncertain situations, people tend to take measures to reduce the impact of such uncertainties (Hofstede, 1980). Uncertainty avoidance theory can explain the behavioral decisions of enterprises facing uncertainty (Kim et al., 2018). Economic policy uncertainty refers micro-market entities’ inability to predict how the government will change its current economic policy (Baker et al., 2016; Gulen and Ion, 2016). Information loss occurs when the uncertainty of economic policies is high, which aggravates information asymmetry, making it difficult for enterprises to predict future changes in the economic environment and to make decisions (Ilut and Schneider, 2014). At present, green finance in China is developing rapidly but is not perfect. Enterprises may face greater financing constraints in energy conservation and emission reduction. The benefits of using funds for green technological innovation are uncertain, making it difficult for enterprises to make green financing decisions independently.

When the cost of making an optimal decision independently is high, imitating and learning from others is the optimal decision (Conlisk, 1980). According to the social learning theory, individual cognition and decision-making behavior are influenced by the external environment, especially the behavior of similar individuals. Peer behavior implies important information related to decision-making. Manski (2000) summarized peer effects into three interaction mechanisms: preference interaction, expectation interaction, and action restriction interaction. Among them, the expectation interaction mechanism emphasizes the role of peer effects in the acquisition of information by individuals or companies. When making green financing decisions, enterprises observe peer behavior in various ways, which is conducive to obtaining more comprehensive information and making decisions (Banerjee, 1992; Bikhchandani and Huang, 1993). Moreover, it plays a more obvious role when the uncertainty of economic policies is high, or the information quality of enterprises is poor (Dodgson, 1993). Therefore, if enterprise managers can obtain useful information from the peer companies’ green financing behavior to supplement their own information, this behavior will transmit useful information to the enterprise. Consequently, in the case of high economic policy uncertainty, peer effects produce positive information externalities, thereby promoting green financing behavior of enterprises. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis 1.

H1. In the peer effects of enterprise green financing behavior, economic policy uncertainty has a positive moderating effect.

Second, using the funds obtained from green financing for energy conservation and emission reduction is conducive to environmental protection, producing positive externalities and safeguarding social interests along with pursuing enterprises’ own interests (McWilliams and Siegel, 2001), which is a manifestation of enterprises undertaking social responsibilities. As the current domestic green finance system is not perfect, enterprises may lack awareness on environmental protection and pay more attention to short-term benefits. Therefore, they are reluctant to carry out green financing for green technology innovation, energy conservation, and emission reduction. However, the higher the corporate social responsibility, the higher the corporate information transparency and the lower the degree of information asymmetry with stakeholders (Pan et al., 2015), which enhances the visibility and reputation of enterprises in the capital market (Manski, 2000; Bikhchandani and Sharma, 2000).

At the same time, peer companies’ green financing behavior indicates that they bear more social responsibilities, which leads to revenue externalities and building a good corporate image as well as accumulating social capital for investors and consumers with environmental awareness (Hong et al., 2019; Lins et al., 2017). The green financing behaviors of listed companies mainly include green credit and green equity financing. For green credit, corporate social responsibility commitment can compensate for insufficient information reflected in financial reports, reduce information asymmetry between banks and enterprises, and enable enterprises to obtain more credit funds (Goss and Roberts, 2011). For green equity financing, corporate social responsibility signals to the market the enterprise’s good operating condition and initiates social responsibility, likely enhancing investors’ confidence and enabling enterprises to finance at a lower capital cost (El Ghoul et al., 2011). Furthermore, when peer companies use green financing to obtain funds for green technological innovation and more environment-friendly production, they gain advantages in product market competition (Flammer, 2015). Therefore, enterprises tend to imitate the behavior of peer companies under the influence of peer companies’ green financing behavior to avoid more disclosure and reputation costs (Scharfstein and Stein, 1990). Based on the analysis, this study proposes research hypothesis 2.

H2. In the peer effects of enterprise green financing behavior, corporate social responsibility commitment has a positive moderating effect.

3 Model design and variable description

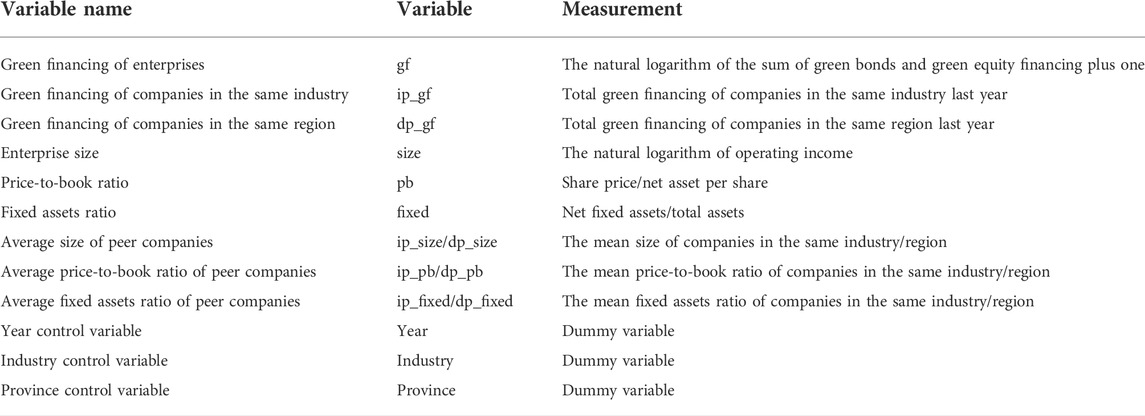

3.1 Variable definition

3.1.1 Explained variable

The explained variable is the green financing of enterprises. Green financing of enterprises mainly includes green credit, green equity financing, green bonds, green funds, and green insurance. Among them, green credit and green equity financing are the most relevant parts of listed companies and those with relatively complete data and clear indicators. Therefore, this study used the sum of green credit and green-related equity financing as data for enterprise green financing.

We downloaded all bond issuance and equity financing information for listed companies from 2011 to 2020 from the Wind database. For green credit, we complied with the definition of green bond given by the China Securities Regulatory Commission—securities that raise funds specifically to pay for green industries, green projects, or green economic activities that meet the specified conditions and are issued in accordance with legal procedures with the condition to repay principal and interest. Due to the lack of a unified definition and identification standards for green equity financing, following the definition of green bond, we manually screened the project data in line with the definition of green finance as per the company’s equity financing purpose. In particular, corporate equity financing aims to support energy conservation and emissions reduction, technology reform, green urbanization, clean and efficient use of energy, new energy development and utilization, recycling economy development, water resources saving and unconventional water resources development and utilization, pollution control, ecological forestry, energy conservation, environmental protection, low-carbon industry, ecological civilization first demonstration pilot demonstration experiment, low-carbon pilot demonstration, and other green, circular, and low-carbon development projects. The final green financing (gf) indicator consists of the natural logarithm of the sum of green bonds and green equity financing, plus one.

3.1.2 Core explanatory variable

Referring to He and Tian (2013), the green financing index of peer companies in this study was measured by the natural logarithm of the total green financing amount plus one of the peer companies in the same industry/region last year. Among them, the green financing of enterprises in the same industry is represented by ip_gf, while the green financing of enterprises in the same region is represented by dp_gf.

3.1.3 Other variables

According to Deng et al. (2022), economic uncertainty (epu) is measured by the economic policy uncertainty index constructed by Baker et al. (2016). To obtain the annual data of epu, the general method in the literature is to simply average the monthly data of Baker et al. (2016) and divide it by 100 to obtain the annual epu index.

Corporate social responsibility refers to the fact that in addition to creating profits and pursuing the maximization of shareholder wealth, enterprises should also undertake responsibilities to stakeholders, to promote social interests beyond their own interests and legal requirements (McWilliams and Siegel, 2001). With reference to Zhou (2018) and Han and Li (2021), 12 aspects in the “Basic Information Table of Social Responsibility Report of Listed Companies” of the CSMAR database were selected to reflect the quality of corporate social responsibility information disclosure. Dummy variables were set for each aspect. If disclosed, the value is one; otherwise, it is 0. Finally, the values of the 12 aspects were summed and standardized to obtain corporate social responsibility (res).

3.1.4 Control variables

Following Leary and Roberts (2014), this study selected firm size (size), price-to-book ratio (pb), and fixed assets ratio (fixed) as the firm-specific control variables. Firm size significantly affects its financing decision, as large firms have a tight target debt ratio in contrast to small firms. It is because large companies tend to be conservative about debt financing so that they can remain stable and profitable (Graham and Harvey, 2001), while small companies have limited access to equity capital and are more likely to use bank loans (Chen and Strange, 2005). Besides, companies with high price-to-book ratio prefer low leverage because of their higher financial distress costs. At the same time, they appear to issue stock when their stock price is high to the book value. (Rajan and Zingales, 1995). Moreover, companies with more tangible assets are able to collateralize and have few debt-related agency problems (Bhabra et al., 2008; Qian et al., 2009; Chang et al., 2014). We also included peer companies’ averages to control for the contextual effects and denote them by the prefix “ip_” or “dp_.”

Simultaneously, this study controlled the fixed effects of year, industry, and region in the regression to exclude their influence on the empirical results. To test peer effects in the same industry, year and region fixed effects were controlled, while year and industry fixed effects were controlled to test peer effects in the same region.

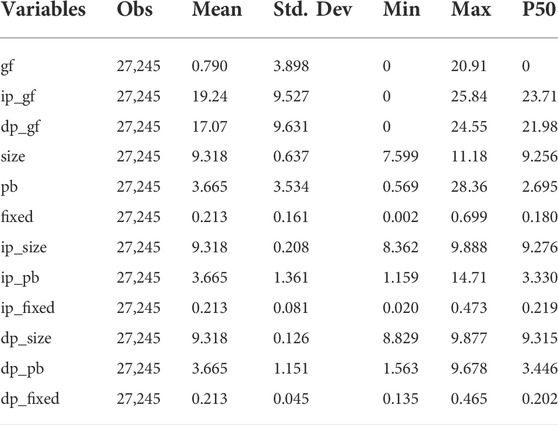

In this study, 1% winsorize truncation processing was carried out for all non-continuous variables to avoid the influence of extreme values. Tables 1, 2 present all variable definitions and descriptive statistics.

3.2 Model design

Relying on Leary and Roberts (2014), Seo (2021), and Gangopadhyay and Nilakantan (2021), this study used the following regression model to test the hypothesis:

where

To further test the influencing mechanism of peer effects on enterprise green financing, the following model was constructed in this study.

Here, epu represents economic policy uncertainty, res represents corporate social responsibility commitment, epu_i is the cross product of epu and ip_gf, epu_d is the cross product of epu and dp_gf, res_i is the cross product of res and ip_gf, and res _d is the cross product of res and dp_gf.

3.3 Data source

This study selected all A-share listed companies from 2011 to 2020 as the original sample, and the data came from China’s Wind database and CSMAR database. In total, 27,245 observations were obtained, excluding financial listed companies and ST2 companies.

4 Emperical analysis

4.1 Regression analysis

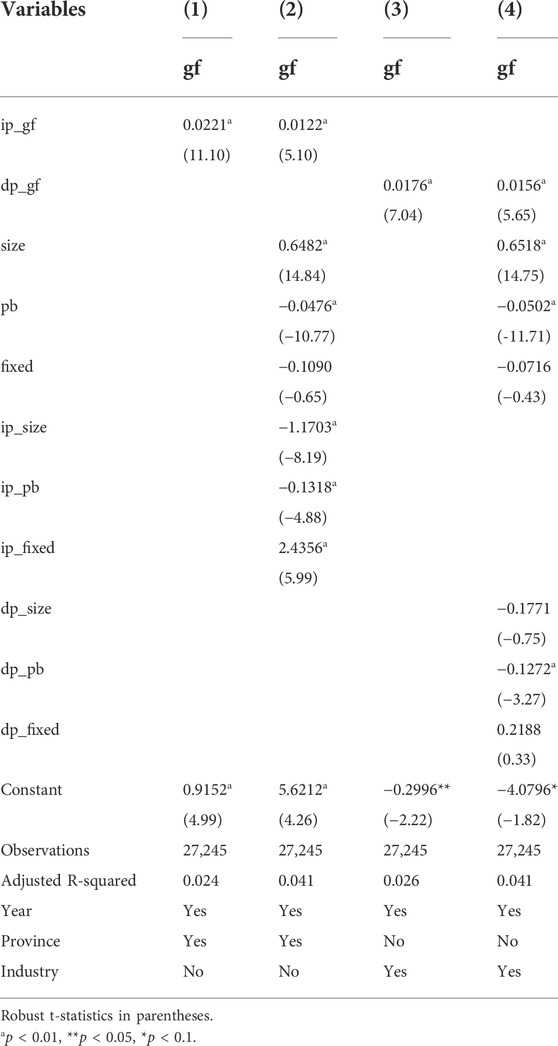

First, we tested whether peer effects existed in enterprises green financing. According to Gangopadhyay and Nilakantan (2021), contextual effects exist if enterprise green financing changes with peer companies’ characteristics (e.g., size, price-to-book ratio, and fixed assets ratio), whereas endogenous effects exist if enterprise green financing changes with peer companies’ behavior (i.e., peer companies’ green financing behavior). We focused on endogenous effects in this study.

The results are shown in Table 3. Columns (1) and (3) do not add control variables, whereas columns (2) and (4) do. In addition, columns (1) and (2) test peer effects in the same industry, whereas columns (3) and (4) test peer effects in the same region. The empirical results show that the coefficients of peer companies’ green financing behavior in the same industry are 0.0221 and 0.0122 without and with control variables, respectively, both of which are significantly positive at the 1% level. The estimated coefficients of peer companies’ green financing behavior in the same region are 0.0176 and 0.0156 without and with control variables, respectively, which are both significantly positive at the 1% level. This result indicates that endogenous effects exist in enterprise green financing behavior. Besides, the coefficients of the contextual variables (i.e., size, price-to-book ratio, and fixed assets ratio) in the same industry are individually significant at the 1% level, which indicates that contextual effects exist in industry group. Meanwhile, the results show that contextual effects in region group are not significant. Therefore, the results indicate that peer effects exist, and have an important effect on enterprise green financing behavior.

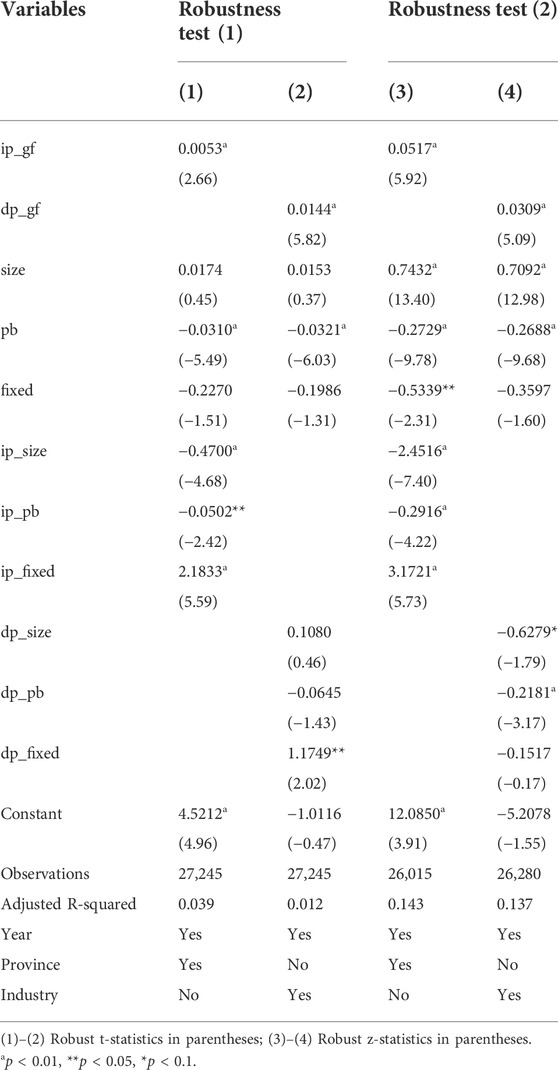

4.2 Robustness test

4.2.1 Robustness test

This study adopted the measure of transformed explained variables to conduct the robustness test (Table 4). In robustness test (1), the explained variable was replaced by gf1, measured by dividing the sum of corporate green bonds and green equity financing by total assets and multiplying by 100. In the regression results, the coefficients of endogenous variables (i.e., peer companies’ green financing behavior in the same industry/region) are 0.0053 and 0.0144, respectively, both of which are significantly positive at the 1% level. In addition, the coefficients of the contextual variables (i.e., size, price-to-book ratio, and fixed assets ratio) in the same industry are individually significant. It is consistent with the above conclusion.

In the robustness test (2), gf_dummy was selected as the explained variable, and the value was set as one if the enterprise had green financing behavior and 0 otherwise. The results show that the coefficients of endogenous variables (i.e., peer companies’ green financing behavior in the same industry/region) are 0.0517 and 0.0309, both significantly positive at the 1% level. The coefficients of the contextual variables (i.e., size, price-to-book ratio, and fixed assets ratio) in the same industry are individually significant at the 1% level.

Therefore, the conclusion is robust. Peer effects exist in enterprise green financing, in which endogenous effects exist in both industry and region group, but contextual effects exist only in industry group.

4.2.2 Endogeneity test

The green financing behavior of enterprises and that of peer companies will lead to the endogeneity problem due to the common influencing factors in the industry or region, such as the same macroeconomic policy guidance or the same economic cycle. Therefore, the endogeneity test in this study selected the lagged idiosyncratic equity return shocks of peer companies as an instrumental variable to identify peer effects in enterprise green financing (Leary and Roberts, 2014; Adhikari and Agrawal, 2018). This instrumental variable will verify whether the green financing behavior of peer companies could promote green financing of the enterprise.

The instrumental variable conforms to the two constraints of correlation and exogeneity. On the one hand, it is correlated with endogenous variables, and the stock price will have an impact on enterprise green financing. On the other hand, the idiosyncratic rate of return only contains the stock’s information. Therefore, the idiosyncratic rate of return of peer companies does not include factors that affect the entire market and industry and thus does not affect the green financing behavior of the enterprise.

The following regression model was used to construct the instrumental variable:

Among them,

The model was regressed at the beginning of each year, using the data from the previous 36 months. Then, we calculated the expected excess return (

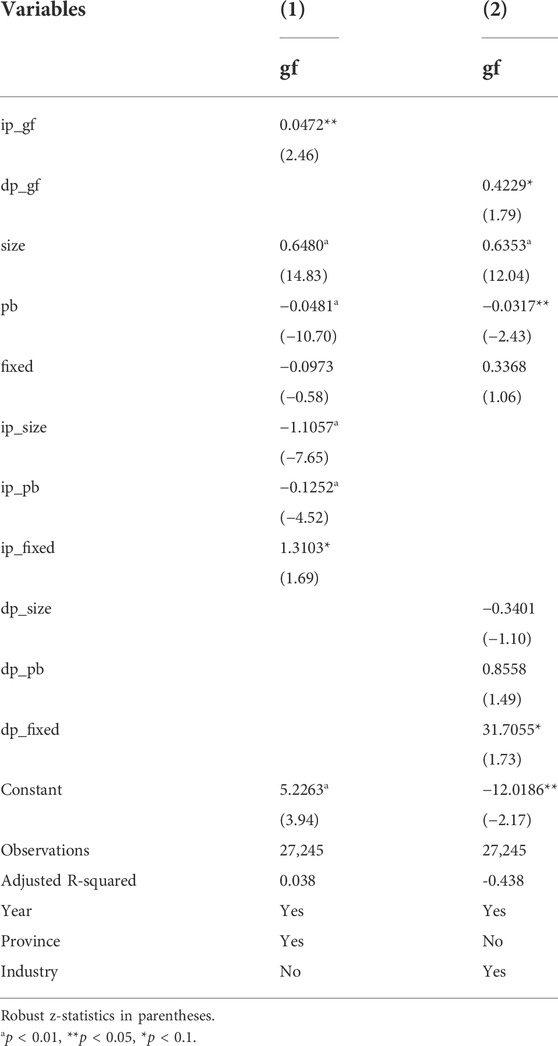

The 2SLS regression was performed with instrumental variables, and columns (1) and (2) in Table 5 show the endogeneity test results. The results show that the coefficients of endogenous variables (i.e., peer companies’ green financing behavior in the same industry/region) are 0.0472 and 0.4229, significantly positive at the 5% and 10% level, respectively. The coefficients of the contextual variables (i.e., size, price-to-book ratio, and fixed assets ratio) in the same industry are individually significant. The results show that peer effects exist in enterprise green financing behavior, and the green financing behavior of peer companies has a positive and significant impact on enterprise green financing, which is consistent with previous results.

4.2.3 Propensity score matching

The regression coefficients estimated using the above methods may be biased from the true average causal effect. Rosenbaum and Rubin (1983) proposed the matching method which constructed a control group with characteristics similar to the experimental group by matching the one-dimensional index to make the counterfactual results of the experimental group consistent with the observation results of the control group and estimate the average causal effect more accurately. King and Nielsen (2019) pointed out the advantage of the matching method: It can determine hidden random experimental samples in the sample data to estimate the average causal effect more accurately.

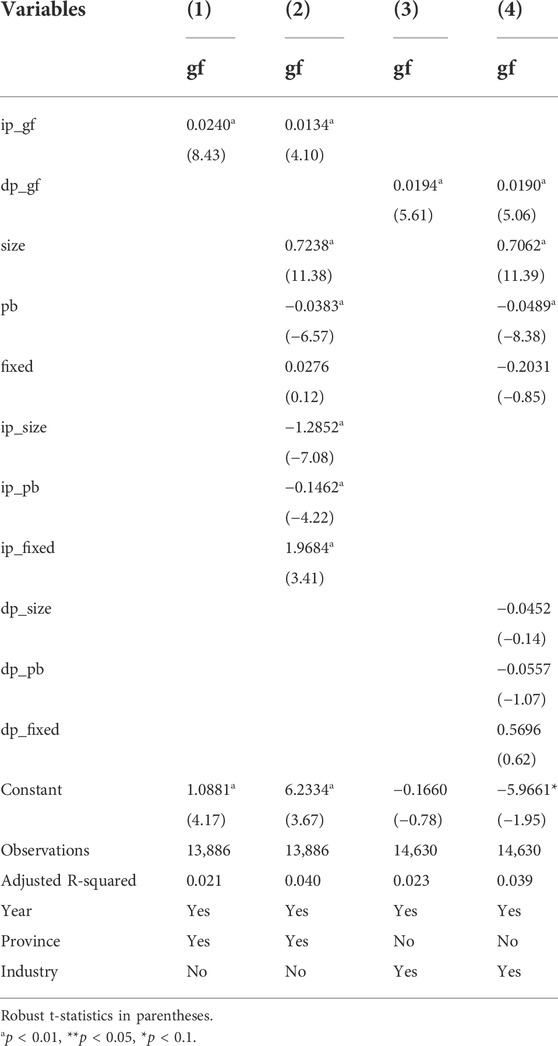

In this study, all firm characteristic variables (i.e., size, price-to-book ratio, and fixed assets ratio) were selected as covariates for propensity score matching, and the matched samples were subjected to regression analysis. As shown in Table 6, the results, after propensity score matching analysis and regression, reveal that the coefficients of peer companies’ green financing behavior in the same industry are 0.0240 and 0.0134 without and with control variables, respectively, both of which are significantly positive at the 1% level. The coefficients of peer companies’ green financing behavior in the same region are 0.0194 and 0.0190 without and with control variables, respectively, which are both significantly positive at the 1% level. The coefficients of the contextual variables (i.e., size, price-to-book ratio, and fixed assets ratio) in the same industry are individually significant at the 1% level. Hence, conclusions were further verified that there were peer effects in enterprise green financing behavior. Endogenous effects exist in both industry group and region group, while contextual effects exist only in industry group. In other words, peer companies’ green financing behavior significantly promotes enterprise green financing behavior.

5 Test of influence mechanism

Two tests based on the above analysis were conducted to explore the influence mechanism of peer effects on enterprise green financing behavior.

On the one hand, when the uncertainty of economic policies is high, the lack of external information aggravates the problem of information asymmetry (Ilut and Schneider, 2014). To mitigate the impact of such uncertainty on financing decisions (Kim et al., 2018), enterprises tend to observe and imitate the green financing behavior of their peers (Conlisk, 1980; Manski, 2000). The green financing behavior of peer companies provides comprehensive and useful information for enterprises (Banerjee, 1992; Bikhchandani and Huang, 1993), thus compensating for the lack of information in the context of uncertainty and enhancing the information environment of enterprises (Dodgson, 1993). Therefore, enterprises are more inclined to make green financing decisions by observing the effect of green financing implemented by peer companies. In other words, when economic policy uncertainty is higher, the green financing behavior of peer companies significantly promotes enterprise green financing behavior. To test the influence mechanism of economic policy uncertainty, this study used the Economic Policy Uncertainty Index (epu) constructed by Baker et al. (2016) to conduct an empirical test.

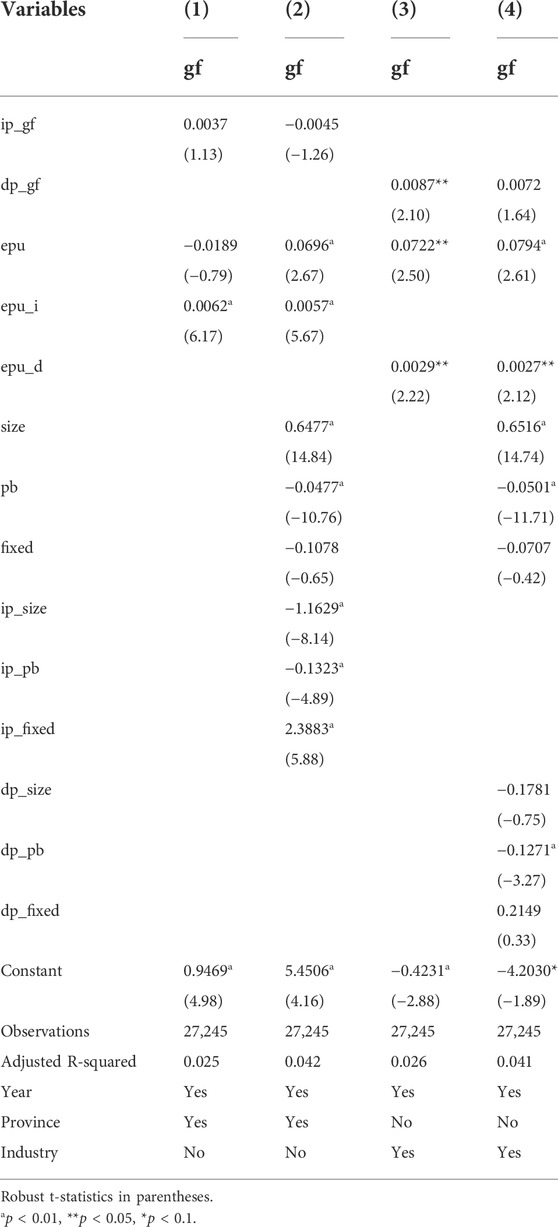

Table 7 shows the impact of economic policy uncertainty on the peer effects of enterprise green financing in the same industry/region. The coefficients of peer companies’ green financing behavior in the same industry (epu_i) are 0.0062 and 0.0057, without and with control variables, respectively, which are significant at the 1% level. The coefficients of enterprise green financing in the same region (epu_d) are 0.0029 and 0.0027, without and with control variables, respectively, which are significant at the 5% level. The empirical results show that when the economic policy uncertainty is higher, the green financing behavior of peer companies significantly promotes the green financing behavior of enterprises. Economic policy uncertainty has a positive moderating effect on the peer effects of enterprise green financing behavior.

On the other hand, when peer companies use funds obtained from green financing for energy conservation and emission reduction, it is conducive to environmental protection and produce positive externalities. Besides pursuing their own interests, peer companies maintain their social interests as well. Therefore, this is a manifestation of companies initiating undertaking social responsibility. By carrying out green financing and actively assuming social responsibilities, peer companies improve their information transparency and reduce the degree of information asymmetry with stakeholders (Pan et al., 2015), thereby gaining good visibility and reputation (Manski, 2000; Bikhchandani and Sharma, 2000). Simultaneously, green financing of peer companies can establish a good corporate image for environmentally conscious consumers and investors (Hong et al., 2019; Lins et al., 2017) to gain a competitive advantage in the product market (Flammer, 2015). Therefore, the green financing behavior of peer companies with higher social responsibility will increase disclosure cost and reputation cost for enterprises. To avoid these costs, enterprises will imitate the green financing behavior of peer companies, which will significantly promote the green financing behavior of enterprises.

To test the influence of corporate social responsibility commitment on the peer effects of enterprise green financing, this study, referring to Zhou (2018) and Han and Li (2021), selected 12 aspects from the Basic Information Sheet of Social Responsibility Report of Listed Companies in the CSMAR database to reflect the quality of corporate social responsibility information disclosure. Dummy variables were set for each aspect. If disclosed, the value was one; otherwise, it was 0. Finally, the values of the 12 aspects were summed up and standardized to obtain corporate social responsibility (res).

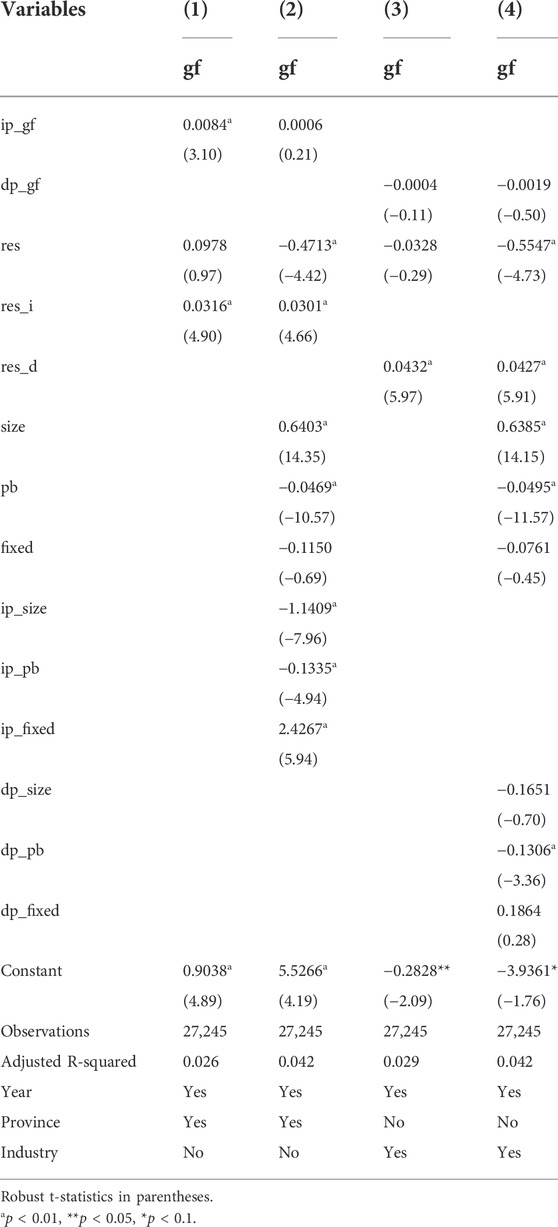

Table 8 shows the impact of corporate social responsibility undertaking on the peer effects of enterprise green financing in the same industry/region. The results show that the coefficients of res_i are 0.0316 and 0.0301, without and with control variables, respectively, which are significant at the 1% level. The coefficients of res_d are 0.0432 and 0.0427, without and with control variables, respectively, which are significant at the 1% level. The results show that when corporate social responsibility commitment is higher, the green financing behavior of peer companies will significantly promote enterprise green financing behavior. Corporate social responsibility commitment has a positive moderating effect on the peer effects of enterprise green financing behavior.

6 Conclusion and policy implication

This study empirically tested peer effects on the green financing behavior of Chinese listed companies. The following conclusions were obtained.

1) The enterprise’s green financing behavior increased significantly with its peer companies’ (i.e., other companies in the same industry or the same region) green financing behavior, and responded to peer companies’ characteristics in the same industry, which indicated that peer effects existed in enterprise green financing behavior.

2) When economic policy uncertainty was higher, the green financing behavior of peer companies significantly promoted the enterprise green financing behavior. The green financing behavior of peer companies provided comprehensive and useful information for enterprises, thus enhancing their information environment and reducing external uncertainties so that they could make green financing decisions at a lower cost.

3) When corporate social responsibility commitment was higher, the green financing behavior of peer companies significantly promoted the enterprises’ green financing behavior. The green financing behavior of peer companies would increase the disclosure and reputation costs of enterprises in capital markets.

Based on the above research, this study proposes the following policy implications: First, the government should establish a network including companies in the same industry and region, so that enterprises can better observe and learn from the green financing behavior and effectiveness of their peers and provide reference experience for themselves in green financing and environmental protection at a lower cost. Second, in the further development of green finance, the government should focus on the industrial/regional situation to conduct green finance. To make full use of peer effects in enterprise green financing, the government should further promote and encourage enterprises with green financing and provide them with financial support by establishing typical enterprises, pilot cities, and other measures to promote the overall green financing behavior of enterprises in the same industry/region. Then promote their green technological innovation, energy conservation, and emission reduction and finally achieve high-quality economic development.

This study tested peer effects in enterprise green financing behavior using samples of Chinese A-share listed companies. There are some differences between China and other countries in the green awareness of consumers and entrepreneurs and the development of green finance, so enterprise green financing behavior can also be different. Hence, future research could be extended to other countries and regions. Also, differences in the development model of green finance between China and other countries lead to differences in the composition of green financial products. Therefore, when using data from other countries for future research, a reasonable measurement method of enterprise green financing behavior should be considered. Lastly, future research could further explore the transmission mechanism of the peer effects in enterprise green financing behavior and its possible economic consequences.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

SY: conceptualization, methodology, and supervision. HZ: data curation, writing—original draft, and writing—review and editing. QZ: data curation, methodology, analysis, and writing—review and editing. TL: conceptualization, methodology, supervision and funding. All authors: contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This paper was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China (18BGL090), “Research on the Impact of Cross-level Corporate Social Networks on Dual Innovation in the New Era.”

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1On 31 August 2016, the People’s Bank of China, the Ministry of Finance, the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Environmental Protection, the China Banking Regulatory Commission, the China Securities Regulatory Commission, and the China Insurance Regulatory Commission issued the Guidance on Building a Green Financial System.

2On 22 April 1998, the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges announced that, according to the stock listing rules implemented in 1998, the trading of shares of listed companies with abnormal financial or other conditions would be treated with special treatment (abbreviated as “ST” in English). In terms of stocks, ST refers to stocks of Chinese listed companies that suffered losses for two consecutive years and received special treatment. In this paper, ST companies are excluded to prevent abnormal financial condition samples from affecting the results of the study.

References

Adhikari, B. K., and Agrawal, A. (2018). Peer influence on payout policies. J. Corp. Finance 48, 615–637. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2017.12.010

Amighini, A., Giudici, P., and Ruet, J. (2022). Green finance: An empirical analysis of the green climate fund portfolio structure. J. Clean. Prod. 350, 131383. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.131383

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., and Davis, S. J. (2016). Measuring economic policy uncertainty. Q. J. Econ. 131, 1593–1636. doi:10.1093/qje/qjw024

Banerjee, A. V. (1992). A simple model of herd behavior. Q. J. Econ. 107, 797–817. doi:10.2307/2118364

Bhabra, H. S., Liu, T., and Tirtiroglu, D. (2008). Capital structure choice in a nascent market: Evidence from listed firms in China. Financ. Manage. 37, 341–364. doi:10.1111/j.1755-053X.2008.00015.x

Bikhchandani, S., and Huang, C. (1993). The economics of treasury securities markets. J. Econ. Perspect. 7, 117–134. doi:10.1257/jep.7.3.117

Bikhchandani, S., and Sharma, S. (2000). Herd behavior in financial markets. IMF Staff Pap. 47, 279–310.

Bizjak, J. M., Lemmon, M. L., and Naveen, L. (2008). Does the use of peer groups contribute to higher pay and less efficient compensation? J. Financial Econ. 90, 152–168. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2007.08.007

Bustamante, M. C., and Frésard, L. (2021). Does firm investment respond to peers’ investment? Manage. Sci. 67, 4703–4724. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2020.3695

Cao, B., and Wang, S. (2017). Opening up, international trade, and green technology progress. J. Clean. Prod. 142, 1002–1012. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.08.145

Cao, J., Liang, H., and Zhan, X. (2019). Peer effects of corporate social responsibility. Manage. Sci. 65, 5487–5503. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2018.3100

Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. J. Finance 52, 57–82. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb03808.x

Chang, C., Chen, X., and Liao, G. (2014). What are the reliably important determinants of capital structure in China? Pacific-Basin Finance J. 30, 87–113. doi:10.1016/j.pacfin.2014.06.001

Chen, J., and Strange, R. (2005). The determinants of capital structure: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. Econ. Change 38, 11–35. doi:10.1007/s10644-005-4521-7

Chen, J. W., Jiang, N. P., and Li, X. (2019). Basic logic, optimal boundary and orientation choice of “green finance”. Reform 7, 119–131.

Conlisk, J. (1980). Costly optimizers versus cheap imitators. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 1, 275–293. doi:10.1016/0167-2681(80)90004-9

Deng, W., Song, Q. H., and Yang, M. (2022). Economic policy uncertainty and assets risk aversion of commercial banks. China Econ. Q. 22, 217–236. doi:10.13821/j.cnki.ceq.2022.01.11

Devenow, A., and Welch, I. (1996). Rational herding in financial economics. Eur. Econ. Rev. 40, 603–615. doi:10.1016/0014-2921(95)00073-9

Ding, N., Ren, Y. N., and Zuo, Y. (2020). Do the losses of the green-credit policy outweigh the gains? A PSM-DID cost-efficiency analysis based on resource allocation. J. Financial Res. 478, 112–130.

Dodgson, M. (1993). Organizational learning: A review of some literatures. Organ. Stud. 14, 375–394. doi:10.1177/017084069301400303

Du, Y. C., Ge, C. Z., He, L., and Lu, L. N. (2017). Suggestions for the green transformation and upgrading of traditional industry in Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 27, 107–110.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., Kwok, C. C. Y., and Mishra, D. R. (2011). Does corporate social responsibility affect the cost of capital? J. Bank. Finance 35, 2388–2406. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2011.02.007

Fan, H., Peng, Y., Wang, H., and Xu, Z. (2021). Greening through finance? J. Dev. Econ. 152, 102683. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2021.102683

Fang, Z., Razzaq, A., Mohsin, M., and Irfan, M. (2022). Spatial spillovers and threshold effects of internet development and entrepreneurship on green innovation efficiency in China. Technol. Soc. 68, 101844. doi:10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101844

Faulkender, M., and Yang, J. (2013). Is disclosure an effective cleansing mechanism? The dynamics of compensation peer benchmarking. Rev. Financ. Stud. 26, 806–839. doi:10.1093/rfs/hhs115

Feng, G. J., and Wang, J. Q. (2021). Cash dividend distribution and its peer effect in the social network. Manag. Rev. 33, 255–268. doi:10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2021.03.022

Flammer, C. (2021). Corporate green bonds. J. Financial Econ. 142, 499–516. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2021.01.010

Flammer, C. (2015). Does corporate social responsibility lead to superior financial performance? A regression discontinuity approach. Manage. Sci. 61, 2549–2568. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2014.2038

Foucault, T., and Fresard, L. (2014). Learning from peers’ stock prices and corporate investment. SSRN J. 111, 554–577. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2117150

Fu, C., Yang, Z., and Fu, D. G. (2015). Does peer effect affect the goodwill: Empirical evidence from high-premium M&A on the GEM. China Soft Sci. 30, 94–108. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-9753.2015.11.010

Gangopadhyay, P., and Nilakantan, R. (2021). Peer effects and social learning in banks’ investments in information technology. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 75, 456–463. doi:10.1016/j.iref.2021.03.024

Glaeser, E. L., Sacerdote, B. I., and Scheinkman, J. A. (2003). The social multiplier. J. Eur. Econ. Assoc. 1, 345–353. doi:10.1162/154247603322390982

Goss, A., and Roberts, G. S. (2011). The impact of corporate social responsibility on the cost of bank loans. J. Bank. Finance 35, 1794–1810. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.12.002

Graham, J. R., and Harvey, C. R. (2001). The theory and practice of corporate finance: Evidence from the field. SSRN J. 60, 187–243. doi:10.2139/ssrn.220251

Gu, B. B., Chen, F., and Zhang, K. (2021). The policy effect of green finance in promoting industrial transformation and upgrading efficiency in China: Analysis from the perspective of government regulation and public environmental demands. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 28, 47474–47491. doi:10.1007/s11356-021-13944-0

Gu, H., Yan, W., Elahi, E., and Cao, Y. (2020). Air pollution risks human mental health: An implication of two-stages least squares estimation of interaction effects. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 27, 2036–2043. doi:10.1007/s11356-019-06612-x

Gu, Y., Ben, S. L., and Lv, J. M. (2022). Peer effect in merger and acquisition activities and its impact on corporate sustainable development: Evidence from China. Sustainability 14, 3891. doi:10.3390/su14073891

Gulen, H., and Ion, M. (2016). Political uncertainty and corporate investment. SSRN J. 29, 523–564. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2188090

Guo, C. X., Liu, Y. H., Yang, X. Y., and Wang, H. X. (2015). Investment and financing on China’s environmental protection industry: Problems and solutions. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 25, 92–99. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1002-2104.2015.08.012

Han, X., and Li, J. J. (2021). Policy continuity, non-financial enterprises’ shadow banking activities, and social responsibility activities. J. Financial Res. 495, 131–150.

He, J. J., and Tian, X. (2013). The dark side of analyst coverage: The case of innovation. J. Financial Econ. 109, 856–878. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.04.001

Herman, K. S., and Shenk, J. (2021). Pattern discovery for climate and environmental policy indicators. Environ. Sci. Policy 120, 89–98. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2021.02.003

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. Int. Stud. Manag. Organ. 10, 15–41. doi:10.1080/00208825.1980.11656300

Hong, H. G., Kubik, J. D., Liskovich, I., and Scheinkman, J. (2019). Crime, punishment and the value of corporate social responsibility. Working paper, Columbia University. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2492202

Hu, L. F. (2022). Why does corporate investment “follow the trend”?—based on the perspective of the impact of macroeconomic policy uncertainty. Nankai Bus. Rev. 25, 1–30.

Ilut, C. L., and Schneider, M. (2014). Ambiguous business cycles. Am. Econ. Rev. 104, 2368–2399. doi:10.1257/aer.104.8.2368

Jeucken, M. H. A., and Bouma, J. J. (1999). The changing environment of banks. Greener Manag. Int. 27, 20–35. doi:10.9774/GLEAF.3062.1999.au.00005

Jiang, X. L., and Xu, H. L. (2016). Green credit operation mechanism of commercial bank of China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 26, 490–492.

Jin, J. Y., and Han, L. Y. (2016). Development trend and risk characteristics of international green bonds. Stud. Int. Finance 33, 36–44. doi:10.16475/j.cnki.1006-1029.2016.11.004

Kaustia, M., and Rantala, V. (2015). Social learning and corporate peer effects. J. Financial Econ. 117, 653–669. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2015.06.006

Kim, B., Lee, S., and Kang, K. H. (2018). The moderating role of CEO narcissism on the relationship between uncertainty avoidance and CSR. Tour. Manag. 67, 203–213. doi:10.1016/j.tourman.2018.01.018

Kim, Y., Li, H., and Li, S. (2014). Corporate social responsibility and stock price crash risk. J. Bank. Finance 43, 1–13. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2014.02.013

King, G., and Nielsen, R. (2019). Why propensity scores should not Be used for matching. Polit. Anal. 27, 435–454. doi:10.1017/pan.2019.11

Leary, M. T., and Roberts, M. R. (2014). Do peer firms affect corporate financial policy? SSRN J. 69, 139–178. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1623379

Li, G. Q., Fang, X. B., and Liu, M. T. (2021). Will digital inclusive finance make economic development greener? Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 762231. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.762231

Li, Z, Z., Liao, G., Wang, Z., and Huang, Z. (2018). Green loan and subsidy for promoting clean production innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 187, 421–431. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.03.066

Li, Z. S., Su, C., Li, H., and Kong, D. M. (2018). Excess leverage and region—Based corporate peer effects. J. Financial Res. 459, 74–90.

Lian, Y. J., Peng, Z., Cai, J., and Yang, H. S. (2020). Peer effect of capital structure in business cycle. Account. Res., 85–97. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-2886.2020.11.007

Lieberman, M. B., and Asaba, S. (2006). Why do firms imitate each other? Acad. Manage. Rev. 31, 366–385. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.20208686

Lins, K. V., Servaes, H., and Tamayo, A. (2017). Social capital, trust, and firm performance: The value of corporate social responsibility during the financial crisis. J. Finance 72, 1785–1824. doi:10.1111/jofi.12505

Lioui, A., and Sharma, Z. (2012). Environmental corporate social responsibility and financial performance: Disentangling direct and indirect effects. Ecol. Econ. 78, 100–111. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.04.004

Liu, R. Y., Wang, D. Q., Zhang, L., and Zhang, L. H. (2019). Can green financial development promote regional ecological efficiency? A case study of China. Nat. Hazards 95, 325–341. doi:10.1007/s11069-018-3502-x

Liu, S., and Wu, D. (2016). Competing by conducting good deeds: The peer effect of corporate social responsibility. Finance Res. Lett. 16, 47–54. doi:10.1016/j.frl.2015.10.013

Ma, J., Cai, L., Wang, K., Wang, C., Li, X., Zhao, X., et al. (2016). [Costal cartilage for rhinoplasty]. Comp. Econ. Soc. Syst. 32, 25.

Manski, C. F. (2000). Economic analysis of social interactions. J. Econ. Perspect. 14, 115–136. doi:10.1257/jep.14.3.115

Manski, C. F. (1993). Identification of endogenous social effects: The reflection problem. Rev. Econ. Stud. 60, 531. doi:10.2307/2298123

Mcwilliams, A., and Siegel, D. (2001). Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manage. Rev. 26, 117–127. doi:10.5465/AMR.2001.4011987

Pan, L., Lin, C., Lee, S., and Ho, K. (2015). Information ratings and capital structure. J. Corp. Finance 31, 17–32. doi:10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.01.011

Peng, J. Y., and Zheng, Y. H. (2021). Does environmental policy promote energy efficiency? Evidence from China in the context of developing green finance. Front. Environ. Sci. 9, 733349. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2021.733349

Qi, H. J., and Liu, S. Q. (2021). Is there a greenium in the bond market of China? Account. Res. 42, 131–148. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1003-2886.2021.11.010

Qian, Y., Tian, Y., and Wirjanto, T. S. (2009). Do Chinese publicly listed companies adjust their capital structure toward a target level? China Econ. Rev. 20, 662–676. doi:10.1016/j.chieco.2009.06.001

Rajan, R. G., and Zingales, L. (1995). What do we know about capital structure? Some evidence from international data. J. Finance 50, 1421–1460. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.1995.tb05184.x

Ren, S., Hao, Y., and Wu, H. (2022). The role of outward foreign direct investment (OFDI) on green total factor energy efficiency: Does institutional quality matters? Evidence from China. Resour. Policy 76, 102587. doi:10.1016/j.resourpol.2022.102587

Ren, X., Shao, Q., and Zhong, R. (2020). Nexus between green finance, non-fossil energy use, and carbon intensity: Empirical evidence from China based on a vector error correction model. J. Clean. Prod. 277, 122844. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122844

Rosenbaum, P. R., and Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 70, 41–55. doi:10.1093/biomet/70.1.41

Sacerdote, B. (2001). Peer effects with random assignment: Results for dartmouth roommates. SSRN J. 116, 681–704. doi:10.2139/ssrn.203071

Scharfstein, D. S., and Stein, J. C. (1990). Herd behavior and investment: Reply. Am. Econ. Rev. 80, 705–706. doi:10.1257/aer.90.3.705

Seo, H. (2021). Peer effects in corporate disclosure decisions. J. Account. Econ. 71, 101364. doi:10.1016/j.jacceco.2020.101364

Su, D. W., and Lian, L. L. (2018). Does green credit policy affect corporate financing and investment? Evidence from publicly listed firms in pollution-intensive industries. J. Financial Res. 462, 123–137.

Tan, C. C., Wang, Z., and Zhou, P. (2022). Fintech “enabling” and enterprise green innovation: From the perspectives of credit rationing and credit supervision. J. Finance Econ. 48, 1–18. doi:10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.20220519.101

Wang, J. H. (2000). Discussing of the green revolution in financial institutions. Ecol. Econ. 16, 45–48.

Wang, X., and Chu, X. (2022). Research on the peer effect of green technology innovation in manufacturing enterprises: Based on the multi-level context reference points. Nankai Bus. Rev. 25, 68–81. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1008-3448.2022.02.008

Wang, Y., and Cao, T. Q. (2017). On peer effects of corporate philanthropy: A study based on board networks. J. Finance Econ. 43, 69–81. doi:10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.2017.08.006

Wang, Y. L., Lei, X. D., and Long, R. Y. (2021). Can green credit policy promote the corporate investment efficiency?—based on the perspective of high-pollution enterprises’ financial resource allocation. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 31, 123–133. doi:10.12062/cpre.20200629

Wang, Y. L., and Zhou, Y. H. (2022). Green finance development and enterprise innovation. J. Finance Econ. 48, 1–15. doi:10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.20220615.101

Weng, Z. X., Ge, C. Z., Duan, X. M., and Long, F. (2015). Analysis on the green financial products development and innovation in China. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 25, 17–22. doi:10.1016/j.cjca.2015.05.021

White, M. A. (1996). Environmental finance: Value and risk in an age of ecology. Bus. Strategy Environ. 5, 198–206. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-0836(199609)5:33.0.CO;2-4

Wu, G. S. (2022). Research on the spatial impact of green finance on the ecological development of Chinese economy. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 887896. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.887896

Wu, H., Xue, Y., Hao, Y., and Ren, S. (2021). How does internet development affect energy-saving and emission reduction? Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 103, 105577. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2021.105577

Xiong, H., Payne, D., and Kinsella, S. (2016). Peer effects in the diffusion of innovations: A research framework. SSRN J. 63, 1–13. doi:10.2139/ssrn.2606726

Yang, S. L., Zhang, Q. Y., Liu, M. W., and Shi, Q. Q. (2020). Peer Effects”in controlling shareholders’ equity pledge and stock price crash risk. Bus. Manag. J. 42, 94–112. doi:10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2020.12.006

Yu, B. (2021). How does the green credit policy impact on heavy pollution firms’ technological innovation? Bus. Manag. J. 43, 35–51. doi:10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2021.11.003

Zhang, C., Cheng, X. W., and Ma, Y. Y. (2022). Research on the impact of green finance policy on regional green innovation-based on evidence from the pilot zones for green finance reform and innovation. Front. Environ. Sci. 10, 6661. doi:10.3389/fenvs.2022.896661

Zhang, J., Zhou, Y. H., and Yu, X. Y. (2021). The peer effects of firm financialization and the operating risk of the real economy. Finance Trade Econ. 42, 67–80. doi:10.19795/j.cnki.cn11-1166/f.20210804.006

Zhang, X. Y., Wang, C., and Qian, L. L. (2017). A study on ripple effect of stock price: From the perspective of firm investment decisions. J. Finance Econ. 43, 136–148. doi:10.16538/j.cnki.jfe.2017.12.009

Zhao, Y. (2016). Analysis of CEOs’ compensations’ peer effects from China listed companies. China Ind. Econ., 114–129. doi:10.19581/j.cnki.ciejournal.2016.02.009

Zhou, P. (2018). Disclosure of corporate social responsibility and actual tax burden: Walking the talk or logging rolling? Bus. Manag. J. 40, 159–177. doi:10.19616/j.cnki.bmj.2018.03.010

Keywords: green financing, peer effects, green financing behavior, China, sustainable economic development

Citation: Yang S, Zhang H, Zhang Q and Liu T (2022) Peer effects of enterprise green financing behavior: Evidence from China. Front. Environ. Sci. 10:1033868. doi: 10.3389/fenvs.2022.1033868

Received: 01 September 2022; Accepted: 12 October 2022;

Published: 26 October 2022.

Edited by:

Mobeen Ur Rehman, Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology (SZABIST), United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Muhammad Haroon Shah, Wuxi University, ChinaPartha Gangopadhyay, Western Sydney University, Australia

Copyright © 2022 Yang, Zhang, Zhang and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qiuyue Zhang, zqy_bjut@163.com

Songling Yang

Songling Yang  Huining Zhang

Huining Zhang Qiuyue Zhang

Qiuyue Zhang