It is the duty of health information producers to be ‘health-literacy’ friendly in all they do. It is a crucial element of tackling health inequality and misinformation. This was demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Health information must be accessible to all.’’

– Sophie Randall, Director, Patient Information Forum (PIF)

Around half of the population struggles to understand information that can help them manage their own health and care. Understanding health information (health literacy) is essential for taking medications correctly, knowing which health services to use, and managing long-term conditions. The most disadvantaged groups in society are most likely to have limited health literacy. Efforts to improve health literacy could therefore reduce health inequalities.

This Collection brings together messages from research highlighted in accessible summaries - NIHR Alerts - over the past couple of years. It covers research on what happens when health information is not clear; how we can help people understand health information; and which groups of the population may need extra support.

We hope this Collection provides useful pointers for those who provide information and for health and social care professionals. We want to help all members of the population make the best use of health information to manage their own health and wellbeing.

Health literacy widens inequalities

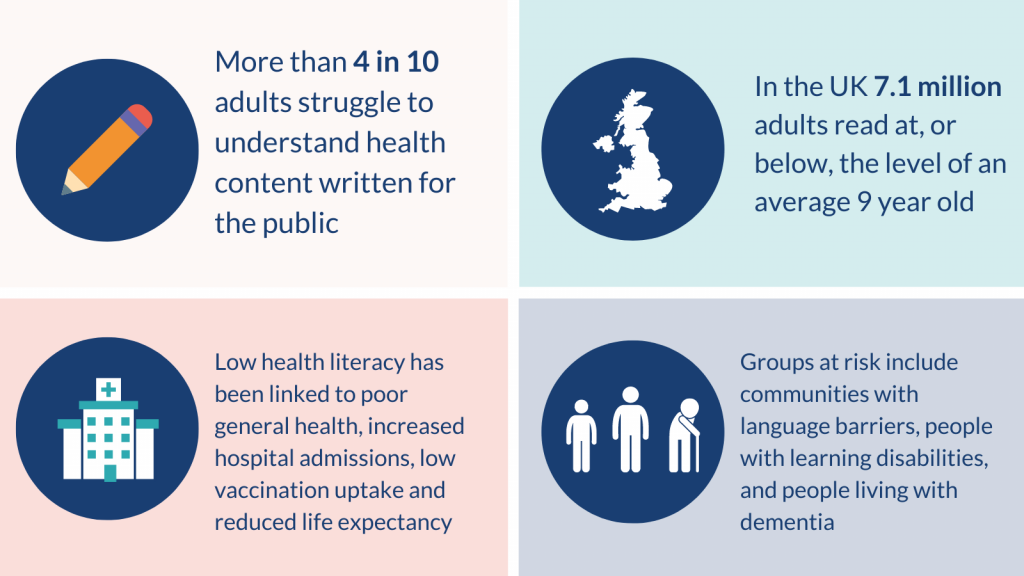

Health materials can be complex, full of medical jargon and numbers, and hard to interpret. In the UK, 7.1 million adults read at, or below, the level of an average 9 year old. More than 4 in 10 adults struggle to understand health content written for the public. And 6 in 10 adults struggle with health information that includes numbers and statistics.

The consequences of not understanding health information are stark. Low health literacy has been linked to poor general health, increased hospital admissions, low use of preventative services (such as vaccination and screening) and reduced life expectancy.

Disadvantaged groups are more likely to have limited health literacy. Improving health literacy could therefore help reduce health inequalities. Groups at risk include communities with language and cultural barriers, and people with conditions that affect comprehension (such as learning disability and dementia). Much health information is found online, which reduces access to information among groups of the population unable to use technology.

UK policy has long recognised the importance of improving health literacy. The National Health Literacy Action Plan for Scotland (2014) calls for everyone involved in health and social care to systematically address health literacy as a priority, as part of efforts to reduce health inequalities. Public Health England (2015) published a health literacy briefing drawing together practical strategies for local areas to consider. Health Education England has developed a Health Literacy Toolkit to help train NHS colleagues, charity organisations, and carers in health literacy. However, literacy levels remain low and inequalities persist.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put health literacy in the spotlight. It has demonstrated the importance of health literacy - to understand social distancing recommendations, why vaccination can bring benefits, and to spot false and possibly harmful information. Action is needed to support all members of the population to use health information to champion their own health and care.

What happens when health information is not clear?

Research shows the impact of understanding health information on a person’s capacity to manage their own health. One study looked at commonly used resources for people with the bone condition, osteoporosis. Researchers found unnecessary technical language and concluded that most of the information was too complex for people to understand. No resources met UK national standards on ease of reading. In addition, some materials were misleading, with inaccuracies and gaps in information. Resources did not present balanced information on the benefits and risks of drug treatments. This could lead to people not taking medicines they are offered, or stopping treatment.

In another study, researchers looked at people with thyroid cancer, who are sometimes asked to adjust their diet (to a low iodine diet) before receiving treatment. The evidence for low iodine diets is mixed, and the information about it varies. People with thyroid cancer were confused about what they needed to do. Some restricted their diet more and for longer than is advised. Others reported feeling distressed and anxious if they had eaten something they thought was incorrect. Their confusion arose from poor quality information and could have a lasting impact; they could blame themselves later if treatment was not successful.

How can we help people understand health information?

Simple, balanced language

People with lived and professional experience can provide helpful guidance. The researchers looking at information on osteoporosis worked with a group of specialist clinicians, GPs, and people with osteoporosis. Their recommendations included terms to avoid (such as describing bone as ‘spongey’), advice to use labelled images, and guidance on how to present balanced information on medications. Information should state who it is for, avoid technical jargon, and explain how reliable the evidence is, they said.

Finding the focus

The focus of information can affect how people act on it. Stressing the personal benefits of the COVID-19 vaccine encouraged people who were hesitant to consider vaccination. This focus was more effective than stressing benefits to the community or addressing safety concerns. The approach only affected people who were hesitant. People who were already willing, or doubtful about, getting vaccinated did not change their mind whatever the focus of the information.

Online information needs to be relevant

Many people access health information online. However, it can be difficult to assess the reliability of online information, or its relevance to an individual’s circumstances. In the study looking at diet adjustment (to a low iodine diet) prior to thyroid cancer treatment, some people in the UK unnecessarily restricted their salt intake. They had found online advice on avoiding salt, from US sources. Salt in the UK does not have iodine added (unlike in the US), and this information was not applicable to them.

The internet can also be a barrier to accessing health information. Women in a British-Pakistani community said they would welcome information about their personal risk of breast cancer as part of screening. However, completing a questionnaire online was a barrier. The women varied in their preferences for how they would like to receive information on their risk. Some preferred letters, some preferred a discussion with their GP, and some wanted both. Digital platforms can help get health content to many people, but the information also needs to be accessible offline.

Visuals, videos, and going viral

Pictures and diagrams can communicate information effectively. A study on alcohol guidelines found that labels including images showing the strength of a drink (the number of units in a serving), as well as an explicit statement of the guidelines, were most effective. These labels improved public understanding of the guidelines and how many servings people could drink.

Videos and theatre performances can also be used to communicate health-related information to a wide audience. Researchers looking at cancer services for teenagers wanted their target audience of young people to know about their results. They teamed up with a theatre company and several young people with cancer, and created a performance inspired by the research. The performance covered the impact of cancer diagnosis, the rights of a young person to be involved in decision-making, and challenges associated with cancer care. The study had a much wider reach and impact than if it had been communicated only in traditional written ways.

Social media can help spread health information. Researchers exploring the views of children and teenagers on getting the COVID-19 vaccine found that many were hesitant. To address their concerns, they wanted to use social media to spread accurate information. Materials aimed at young people, including videos and images, have been posted on TikTok, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Images, animations, and videos can help communicate information to the general public. They are especially important for groups who may need extra support to understand health information.

Who may face extra barriers understanding health information?

People facing language barriers

The researchers exploring communication preferences with women from a British-Pakistani community, also looked at the barriers to attending breast screening. They found that there is no direct translation for the terms ‘mammogram’ or ‘screening’ in the womens’ first languages, Punjabi or Urdu. Lack of literacy meant that translating letters would not necessarily be helpful. Use of family members as translators could mean that not all health information was passed on, often due to embarrassment. Women frequently did not know that translators could be provided by the NHS. They were reluctant to speak with male healthcare professionals, and often unaware that screening takes place in an all-female environment. The researchers recommend that healthcare professionals discuss screening during prior appointments, highlight in invitation letters that screening environments are all-female, and ask women about their communication preferences.

The NIHR Evidence team, in collaboration with Kingston University and St George’s University of London and The Mosaic Community Trust, is exploring how members of Black and South Asian communities access health information. Initial findings suggest that people from these communities prefer to seek health information from experts within their community that are considered credible and trustworthy (local GPs, community groups), or younger family members, rather than using translated summaries. First-hand accounts of lived experiences were also valued. The research suggests that visual formats and videos can overcome language and literacy barriers. They are easily shared on digital platforms, and can reach wide audiences.

People with language difficulties and learning disabilities

People with language difficulties may need extra support to understand information that could affect their health and wellbeing. Research found that young offenders with a language disorder are twice as likely to reoffend within a year as young offenders without such difficulties. People with developmental language disorder (DLD) have difficulty understanding what is said to them and expressing themselves. Young offenders with DLD may be unable to take advantage of rehabilitation services aiming to stop them reoffending. Rehabilitation often involves talking through what happened, listening to victims, and expressing regret. The researchers say extra support is needed for young offenders with language problems, including tailored rehabilitation, and involving speech and language therapists.

Other research has explored the support that people with learning disabilities need to develop romantic relationships. It found that people with learning disabilities placed a high value on these relationships. They benefited from extra opportunities to learn about relationships, for example discussions at support groups or as part of care plans. To share the results more widely, the research team created videos to explain their findings in a clear and simple way. They showed the videos in workshops, and people with learning disabilities said they recognised the experiences described.

In addition to videos, ‘easy-reads’ (text alternatives with images and large, clear font) can help share written information in a clear and easy to understand format. As well as the standard research summary (Alert), an easy-read summary of this research can be found on the NIHR Evidence website.

People living with dementia

People living with dementia face unique challenges when they also have another health condition. Researchers found that people with dementia who also needed cancer treatment often had difficulty retaining information and understanding what was happening. Information about the diagnosis and treatment options was explained too quickly, or in ways that were too complicated. People with dementia who had supportive family carers were more likely to receive appropriate care and treatment.

The researchers suggest that cancer care could be improved for people with dementia with longer appointments, and simpler written explanations (with pictures) that can be taken home. The researchers recommend involving carers, and, where possible, for the same staff member to be available in the same location for each visit.

Communities with low literacy

Many people in Gypsy, Traveller, and Roma communities cannot read. Research exploring end of life care in these communities found that illiteracy was a common barrier to healthcare. Reduced access to services can shorten life expectancy, lower vaccination rates, and increase long-term conditions such as diabetes and heart disease in these communities.

The research found that documents about care options were often unhelpful. This was partly due to low literacy, but also because many families felt they knew how to look after their relatives, and wanted to perform traditional rituals at home rather than in a hospital. The researchers recommend that healthcare professionals take a personalised approach to engaging with these communities, discussing individual preferences and avoiding written materials. Practical information, such as awareness of hospice at home services, could reassure communities that appropriate care is available. Local advocates could provide a bridge between the community and the healthcare systems; people may be more likely to discuss delicate subjects with members of their own communities.

Conclusion

Supporting all members of the population to understand health information can help them manage their own health, wellbeing, and care. The consequences can be far-reaching, influencing individuals’ life opportunities, the NHS’ workload, and care costs.

Information providers including healthcare professionals, NHS Trusts, and health charities can ensure that their content is clear, accessible, and balanced. Information should clearly state how reliable it is (what research it is based on) and the groups of people and locations where it is applicable. Digital platforms can be an extremely effective way of reaching large numbers of people, but they do not work for everyone and materials should also be available offline. Extra support should be considered for groups of the population who struggle to understand information, including those who face language or literacy barriers, or have learning disabilities or dementia. Videos and other visual formats can help overcome some of these barriers, and explain information in an accessible and clear way. Finding the right focus can help the messages resonate with target audiences. Working closely with communities can increase trust and the take-up of health information.

The needs of each group, and of each individual, are unique: their prior experiences, literacy levels, and communication preferences. Consideration of audiences’ needs is the starting point for developing appropriate health information, to allow individuals to manage their own health and care, and move one step closer to tackling health inequalities.

Useful resources

- Content style guide: Health literacy - NHS

- Health Education England Health Literacy Toolkit - NHS

- The Health Literacy Place - NHS Scotland

- Health and Digital Literacy Survey 2019/20, Health literacy matters poster and Covid Choices Survey - Main Findings - Patient Information Forum

- Putting patients first: Championing good practice in combatting digital health inequalities - Patient Coalition for AI, Data and Digital Tech in Health

- Accessible Information Standard: Making health and social care information accessible - NHS

- Health information in other languages - NHS

- Thinking differently about health - The Health Foundation and the FrameWorks Institute

- What we need now: What matters to people for health and care, during COVID-19 and beyond - National Voices

- Health literacy resource library - Health Literacy UK

- Health Information Week: 3 - 10 July 2023

How to cite this Collection: NIHR Evidence: Health information: are you getting your message across?; June 2022; doi: 10.3310/nihrevidence_51109

Author: Deniz Gursul, Research Dissemination Manager, NIHR

Disclaimer: This publication is not a substitute for professional healthcare advice. It provides information about research which is funded or supported by the NIHR. Please note that views expressed are those of the author(s) and reviewer(s) at the time of publication. They do not necessarily reflect the views of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.