Learning from the field and its listserv: Issues that concern health literacy practitioners

Abstract

This study assesses the content of email messages posted to the Health Literacy Discussion List (HLDL) during a two-year period. The study identifies issues of concern to list subscribers, describes the purposes the list serves for health professionals, and contributes to the health literacy literature by providing an email listserv as a research corpus. The authors conducted an inductive qualitative analysis of email posts to the HLDL from October 2013 to October 2015. Using an iterative process, the authors identified descriptive categories for types of posts and topics of posts. The first (SKR) and third (JM) authors reviewed subject lines of all 2,036 posts and brainstormed type and topic categories, independently read and sorted a random sample of 200 posts into those categories, and then discussed discrepancies. Based on the latter experience, the authors combined, added, or excluded certain categories and jointly created a detailed description for each type and topic category. We then sorted another random sample of 200 posts and generated a list of key words relating emails to topic categories. A Cohen’s kappa reliability coefficient was calculated to establish intercoder reliability. The second author (RVR) then conducted key word searches for sorting the remaining 1,836 email posts. The existence and frequency of email clusters and the content of emails in these clusters were used to identify and explore in greater detail the “hot topics” of interest to the field. Our analysis suggests the utility of the HLDL as a platform for sharing information and resources, announcements and calls for action, technical assistance and professional discourse.

1.Introduction

This study assesses the content of email messages posted to the Health Literacy Discussion List (HLDL) during a two-year period. The study identifies issues of concern to list subscribers, describes the purposes the list serves for health professionals, and contributes to the health literacy literature by providing an email listserv as a research corpus.

Listservs are computer-mediated discussion groups by which subscribers can send and receive electronic mail (email) messages. Listservs provide professionals with similar interests the opportunity to ask questions and make requests, share resources and information, and discuss issues of common concern. Subscribers send and receive messages (posts) to all members of the list. Members can either respond to the email messages they receive from the list or simply read the posts and not respond. A key question is what purposes do lists serve for professional communities of practice.

To understand how the HLDL serves the health literacy community of practice, the authors identified categories for types and topics of posts made to the list. We sorted emails into types of posts categories to better understand the utility of the list for members. We sorted emails into topical categories to assess the substantive areas of concern to listserv members.

This paper reviews studies of lists serving professionals and presents background information on the evolution of Health Literacy Discussion List (HLDL). The authors detail the inductive methodology used to identifying types and topics of posts made to the list. We report common themes discussed and suggest the ways in which the list supports subscribers and the health literacy field of research and practice. Finally, we discuss how this work may serve as a model for future research.

2.Background

Electronic discussion lists, also known as Listservs, are used within many professional disciplines to facilitate communication. Professionals with similar interests use listservs to exchange email messages, share information, ask questions, learn from others, and discuss relevant issues.

Professional organizations and associations often maintain listservs as a service to their field. For example, the American Evaluation Association maintains a listserv for members to exchange information and ideas related to evaluation. As new professionals enter the field, the list serves as a forum for offering feedback and soliciting advice [2].

Some discussion lists are unmoderated and allow all messages to go automatically to all list members. Other lists are moderated, meaning all email messages are read by a moderator, before they are allowed through to the group. A moderated format screens for inappropriate posts and may help promote and facilitate interaction.

Listservs are increasingly valued as a setting for investigation. There is a growing body of research looking at how and why groups of professionals such as teachers, nurses, and librarians use listservs and the topics they discuss [1,2,6,11,13,17]. Investigators have developed methodologies for content analysis of emails posted from listservs and demonstrated these methods as reliable and valid ways of conducting research.

In one example, investigators conducted content analysis of emails posted to a discussion list for councilor educators and practitioners [11]. Neukrug and colleagues examined 9,197 emails posted to the list over a three-year period [11]. They identified 20 superordinate and 17 subordinate categories using an inductive approach. The majority of posts represented resource requests (29%) and personal communication (21%). Fifteen percent were categorized as program development, and 7% were jobs related.

Another study identified types of posts and types of knowledge shared by nurses through an online community of practice discussion list [6]. Ten types of posts were identified with 56% categorized as knowledge sharing and 33% as solicitation. The next most common type of post was job postings (6%). Through interviews with list members, Hara, Noriko Hew, Khe Foon [6] found that the moderator was pivotal to facilitating knowledge sharing.

2.1.The Health Literacy Discussion List

Adult educators and health professionals began to identify a link between health and literacy in the early 1990s. The National Adult Literacy Assessment (NALS) reported half of American adults had marginal literacy skills [14]. The findings led to concerns about the complexity of health information and people’s ability to take medicine correctly, self-manage chronic diseases, and fill out medical forms. Numerous studies document the mismatch between the reading level at which health education material are written and the reading skills of the intended audience [12]. Growing evidence points to health literacy as a strong predictor of health status and health outcomes [12].

Health professionals from many disciplines began efforts to reduce the complexity of health information and increase ease of access to services. In this way, health literacy emerged as a professional subspecialty for some and a primary professional identity for others [18]. Further exploration of the link between literacy and health outcomes by researchers created a growing evidence base. As an emerging field, interaction among professionals from health, education and many other backgrounds and training generated health literacy knowledge, intervention tools, and best practices.

In 1996, the Literacy Information and Communication System (LINCS) established the LINCS Health Literacy Discussion List as an ongoing professional development forum for literacy practitioners, healthcare providers, health educators, researchers, policy makers and others to discuss health literacy needs and strategies. At its height, the list reported more than 1,500 subscribers from the United States, Canada, England, Ireland, Taiwan, Austria, New Zealand, The Netherlands, and Israel. List activity dropped when LINCS converted the email format to a web-based platform in 2011. From 2011 to early 2013, the moderator received personal emails from members saying they did not want to log into a web-based platform. Members expressed their preference to read and answer posts through email and voiced a clear dissatisfaction with the loss of professional discourse.

In response, the Institute for Healthcare Advancement (IHA) offered to host a listserv using the original email format. The Health Literacy Discussion List (HLDL) restarted in October 2013. The HLDL has more than 1,600 members and is an active online forum for discussion among a wide range of professionals. The list moderator screens all posts before releasing them to the group and deletes any that are spam. The moderator also monitors the subject lines to make sure they reflect the content of the post. This facilitates future searches through the archives. To encourage discussion, the moderator posts Wednesday Questions and periodically invites guests to facilitate discussion of current topics of interest.

Although studies have analyzed the content of professional listservs to identify utility and topics of interest, none have formally assessed the Health Literacy Discussion List (HLDL).

3.Methods

The authors analyzed 2,036 email posts to the Health Literacy Discussion List (HLDL) during a period of two years (October 2013–October 2015). Subscribers to the listserv agree to have their posts viewed by other subscribers and stored as a body of knowledge that can be searched and referenced for research. We applied a mixed methodological approach of inductive naturalistic inquiry and heuristic decision making to identify thematic codes that emerged from the data [5,9,16]. As such, this research is a descriptive evaluation of text and limited to the specific topics subscribers raise as well as the broader categories of subscriber posts. The authors developed descriptive categories for the types and topics of posts through an iterative process. Types of posts categories provided insight into the function of the listserv for members. Topics of posts categories highlighted the substantive areas of interest to listserv members.

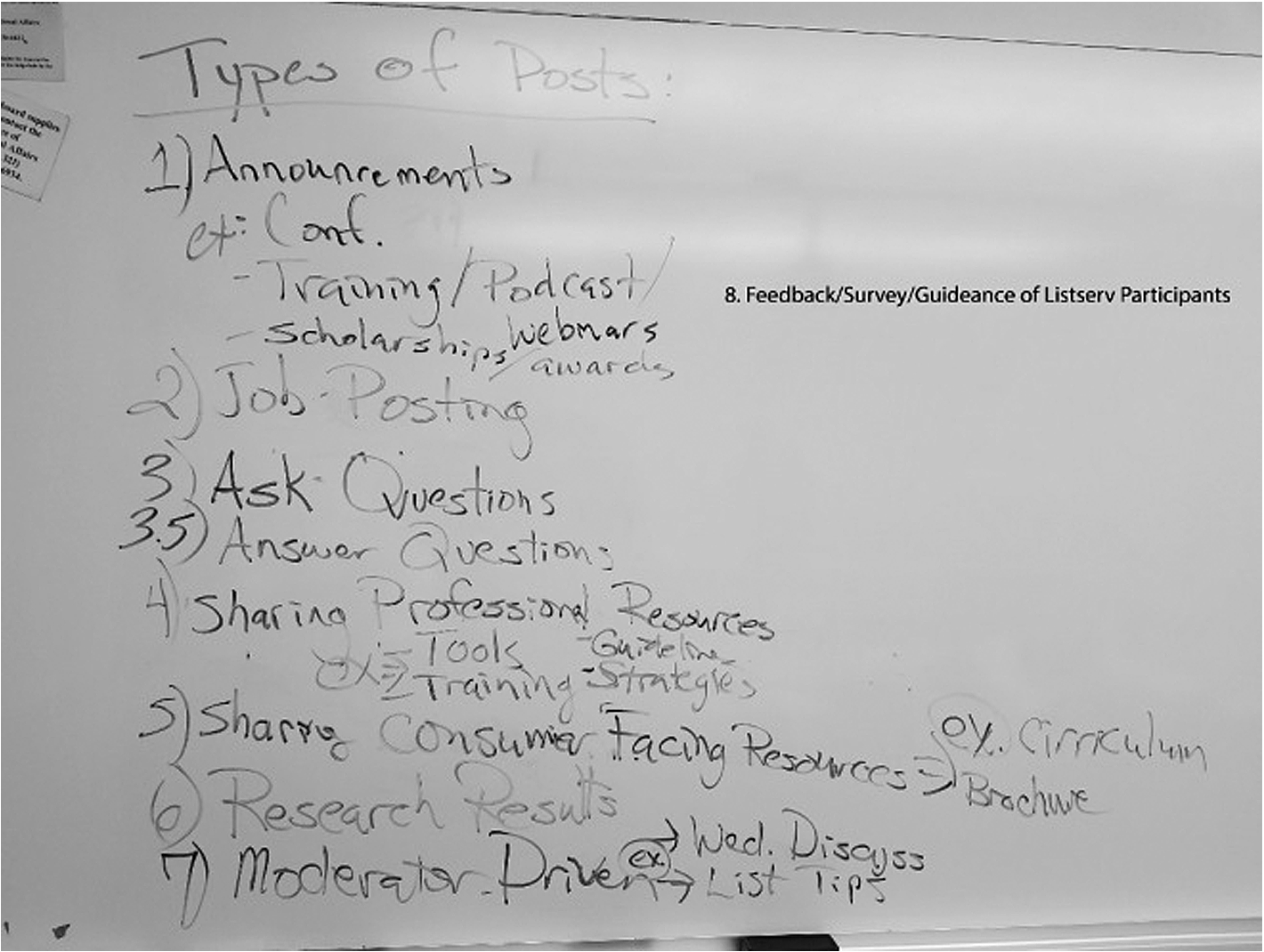

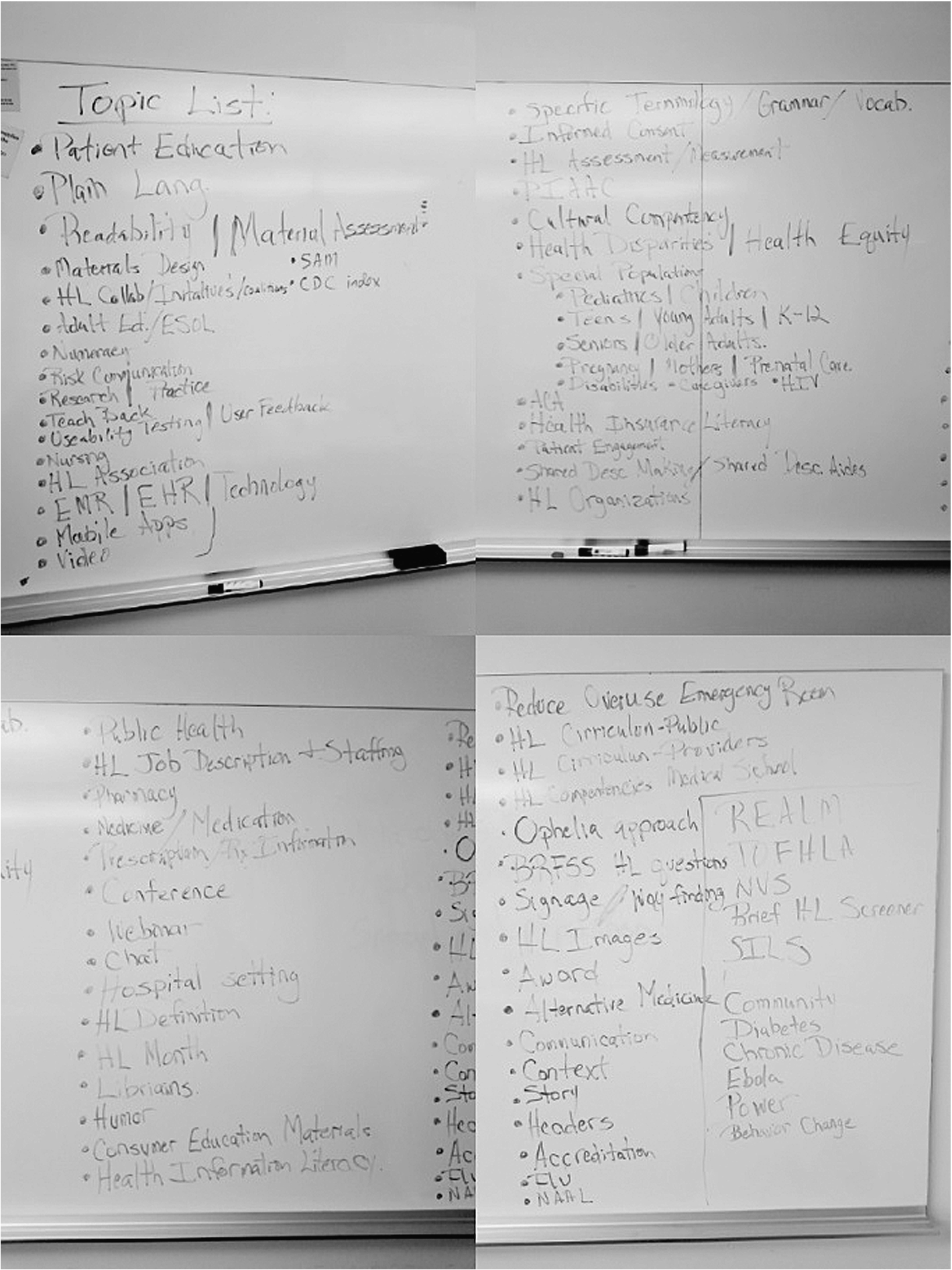

The first (SKR) and third (JM) authors reviewed the subject lines of all 2,036 emails posts as the first step in the iterative process. Following that review we independently developed lists for the types and topics of posts. We combined the lists and placed them on a white board to review and discussion. The second author (RVR) facilitated a collaborative discussion to agree on a common understanding of the types and topics categories. Note: the third author (JM) was the HLDL moderator during the assessed time period, and the first (SKR) and second (RVR) authors were subscribers to the list during the assessed period. Figure 1 displays the preliminary list of eight types of posts categories and Fig. 2 displays the preliminary list of 95 topics of posts categories.

Fig. 1.

Preliminary list of post types.

Fig. 2.

Preliminary list of post topics.

The second iterative step involved creating a “tally sheet” to categorize a random sample of 200 listserv posts into the initial types and topics categories. The 200 posts were selected without replacement to the total 2,036 posts (i.e., 1,836 remaining posts). Each post received a unique post number (P) for identification purposes. SKR and JM independently read each of the 200 posts and categorized posts by type and topical area of interest. The tally sheets were returned to RVR to calculate intercoder reliability. Cohen’s kappa reliability coefficient [3,4] estimates the level of intercoder reliability between raters analyzing qualitative data. Kappa values for the types of posts ranged from 0.42 (a “moderate” level of agreement) to 1.00 (an “almost perfect” level of agreement) [8]. Kappa values for the topical areas ranged from 0.09 (a “slight” level of agreement) to 1.00. The preliminary analyses suggested the need for further refinement as part of the heuristic decision making process [3]. During a weekly research meeting, SKR and JM each described their decision-making process to categorize posts by types and topical areas. RVR facilitated discussions and resolved disagreements on type and topics categorizing through consensus. Discussions lead to the development of a codebook containing the final list of six types of posts in Table 1 and 48 post topics in Table 2. The agreed upon list of types and topics guided the next iterative step.

Table 1

Types of posts

| Categories | Description of categories | |

| 1. | Announcements | This category primarily includes conference announcements and announcements for professional in-person trainings, podcasts, and webinars. |

| 2. | Job postings | Included in this category are job postings from organizations hiring a health literacy position, and also questions about job descriptions. |

| 3. | Asking/answering questions | Posts placed in this category include questions from list members; answers to questions; requests for clarification; and thank you posts to those responding to questions. |

| 4. | Resources | This category includes asking for and sharing professional resources and materials (i.e. teaching tools, trainings, curricula, guidelines, print resources, websites, research articles, and other); and consumer facing resources and materials (i.e. brochures, booklets, curricula, consumer websites and other). |

| 5. | Service | Included in this category are requests for list members to provide feedback or guidance on policy or other issues, complete a questionnaire or survey, and calls for action affecting the field as a whole. |

| 6. | Discussion | Posts in this category were discussions of a theme, new idea or conceptual view of some aspect of health literacy, initiated by a list member or by the moderator. The two types of moderator-initiated posts are Wednesday Questions, posted most weeks and intended to stimulate discussion, and Guest Discussions, events scheduled for a few days to a week, where a guest moderator leads a focused discussion of a topic. |

Table 2

Topics of posts

| Categories | Description of categories | key words | |

| 1. | Affordable Care Act (ACA) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to the U.S. Affordable Care Act (ACA). |

| 2. | Adult basic education (ABE) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to adult education, adult basic education (ABE), English language learning (ELL), ESL, ESOL, learner(s), teacher(s), tutoring. |

| 3. | Alternative medicine(s) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to the alternative medicine(s) or home remedy(ies). |

| 4. | Assessment/measurement: individual | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to health literacy measurement of individuals: screening tool(s), TOFLA, REALM, Newest Vital Signs, single question screen, health literacy assessment of patients, assessment in hospitals. |

| 5. | Assessment/measurement: population | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to health literacy assessment of population(s): HLS-EU-Q, Ophelia, National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NAAL), BRFSS, PIACC. |

| 6. | Association, membership organization | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to a health literacy association, membership organization, HLA, IHLA, AHL, I-HLA. |

| 7. | Award(s), funding | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to health literacy award(s), grant(s), funding, scholarship(s). |

| 8. | Certification, accreditation | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to a health literacy certification, accreditation. |

| 9. | Collaboration, coalition(s), partnership(s) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to collaboration(s), partnership(s), alliance(s) including all references to health literacy coalition(s), collaborate, collaboratively. |

| 10. | Conference(s), meeting(s), | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to a health literacy conference(s), meeting(s), IOM meeting(s), summit, institute. |

| 11. | Consumer education, health education material(s) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to consumer education, health education materials (i.e., print, radio, websites, and other multi-media). Not social media or new technologies. NOT patient education. |

| 12. | Cultural competency | Any post that uses the term cultural competency, culture, cross-cultural, culturally and linguistically appropriate (CLAS). |

| 13. | Curriculum in the community or health setting for patients or the public | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to a curriculum for teaching consumers or patients, community education, HLLI, workshop, K-12 school(s). |

| 14. | Curriculum for training health professionals | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to training health professionals, continuing education, medical school(s), competencies, health professions educator(s), session(s), course(s), HLLI, syllabus, syllabi, webinar(s), professional development. |

| 15. | Disparities, health equity | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to health disparities, health equity, unequal provision of quality health care. NOT social justice, privilege, power. |

| 16. | Definition of health literacy | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to the definition of health literacy or a conceptualization of health literacy (i.e., two-way street concept). |

| 17. | Global, international health literacy | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to global, international, or names a specific country. |

| 18. | Health communication | Any post that uses the term health communication. |

| 19. | Health literacy month | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to health literacy month (HLM). |

| 20. | Health insurance, health insurance literacy | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to health insurance, health insurance literacy. |

| 21. | History (how the field got started) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to the history of the field or how health literacy as a field of study and practice began. |

| 22. | Job announcement(s) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to a health literacy job announcement(s), job description, open position, employment, staff position, consulting. |

| 23. | Health literate organization(s) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to a health literate organization(s), Ten Attributes, assessment of organizational health literacy, health literacy environment(s), measure(s) to assess organizations. |

| 24. | Hospital, clinical setting(s) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to health literacy in hospitals setting(s), clinical setting(s), health care setting(s), doctor’s office, medical center, including subcategories with references to emergency department (ED), emergency room (ER), healthcare system(s), hospital system(s), healthcare system(s), advanced directive(s), nurses, lab results, signage, wayfinding, navigation, navigator, universal precautions, patient safety, patient satisfaction. |

| 25. | Humor | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to humor. |

| 26. | Informed consent | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to informed consent in a hospital or health care setting for surgery or a procedure, or related to research. |

| 27. | Language(s) other than English, interpreter, translation | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to language(s) other than English, interpreter, interpreting, translation, multilingual, multi-lingual, other languages, non-English, Spanish. |

| 28. | Legal | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to legal issues. |

| 29. | Librarian(s), health information literacy | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to librarian(s), library(ies), health information literacy. |

| 30. | Listserv related | Any post that is specifically listserv related such as etiquette and other guidelines from the moderator. |

| 31. | Materials assessment | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to materials assessment, readability, formulas, SMOG, Fry, SAM, CDC Index, PEMAT, check list, user feedback, user testing. |

| 32. | Materials development, plain language materials or websites | Any post that refers to, requests for, or is part of a discussion related to developing plain language, easy-to-read, easy to use materials, website design, website guidelines, writing guidelines, design guidelines, guidelines for forms, survey(s) questionnaire(s), visual(s), image(s), headers, subheaders. |

| 33. | Medicine(s), medication(s) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to medicine(s), medication(s), prescription (RX), labels, inserts, over-the-counter (OTC), pharmacy(ies). |

| 34. | Numeracy | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to numeracy, numerical. |

| 35. | Patient education, patient education material(s) | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to patient education, patient education materials (i.e., print, radio, websites, and other multi-media). Not social media or new technologies. NOT patient education. |

| 36. | Patient engagement | Any post that uses the term patient engagement. |

| 37. | Patient-provider communication | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to patient-provider communication, oral communication, jargon. |

| 38. | Public health, health promotion, social determinants of health | Any post that uses one of these terms public health, health promotion, social determinants of health. |

| 39. | Research | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to research finding(s), method(s), result(s), data, sampling, statistics, article(s), journal, participatory design, participatory research, research questions. NOT related to health literacy measurement or assessment. |

| 40. | Practice, practitioner(s) | Any post that uses the term health literacy practice or practitioner. |

| 41. | Risk communication | Any post that uses the term risk communication. |

| 42. | Shared decision making | Any post that uses the term shared decision making or shared decision making aides. |

| 43. | Social justice | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to social justices, identity, bias, power, privilege, sexual orientation. |

| 44. | Special populations/health topics | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion relating to a specific population group or health topics of concern. Subcategories include pediatric(s), children, child, kids; teens, young adults, adolescent, youth; seniors, older adults, aging; pregnancy, prenatal, mother(s), maternal, maternity; disability(ies), accessibility, accessible; caregiver(s), parent(s); HIV/AIDS; cancer; women; flu; LEP, Immigrant(s), refugee(s), non-English speaking; diabetes; VA, veteran(s); incarcerated, prison, jails, criminal justice; mental health, behavioral health; nutrition; asthma; chronic disease(s); homeless. |

| 45. | Story, narrative | Any post that is a personal story or talks about story as an effective form of communication. |

| 46. | Teach-back | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to teach-back, teachback, teach back. |

| 47. | Technology | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to technology. NOT including websites. Subcategories include chat, electronic medical record (EMR), electronic health records, smartphones, social media, mobile apps. |

| 48. | Terminology, vocabulary, glossary of terms | Any post that refers to or is part of a discussion related to plain language vocabulary, glossary of terms, glossaries, terminology, common term(s). |

A second random sample of 200 email posts were selected from the 1,836 remaining listserv posts. Using a revised “tally sheet” of type and topical areas, SKR and JM independently read and categorized the second sample of posts. The tally sheets were returned to RVR to calculate intercoder reliability. The kappa values for types of posts improved and ranged from 0.90 to 1.00 (an “almost perfect” level of agreement) [15] and kappa values for the topical categories ranged from 0.89 to 1.00 (a “substantial” to “almost perfect” level). To ensure and further validate the reliability for the topical categories of interest, RVR independently categorized the second random sample of 200 posts using the key word search function in Atlis.ti 7 [15]. Atlis.ti 7 key word search function includes the option to search and systematically analyze text using Boolean logic operators (e.g., AND, NOT, OR). Including the key word search results slightly increased the estimated kappa values for topical areas and ranged from 0.91 to 1.00 (an “almost perfect” level). The authors also identified clusters of “hot topics” most frequently discussed by listserv members from the total 2,036 posts. We elaborate further on the identified “hot topics” within the Results section.

4.Results

The authors extracted contributors’ signature lines to examine the characteristics (i.e., location, degree(s) earned, and position title) of listserv members and identified 322. Of the 322 unique contributors to the list during the two-year period, 289 included a physical address within the signature. Nine countries were represented including Australia, Canada, Israel, Italy, New Zealand, Pakistan, The Netherlands, United Kingdom, and the United States. The majority (89%) of addresses were located within the United States. We did not observe contributions to the listserv from South America and Africa. In terms of formal training, 22% of members listed a degree in Public Health, 17% in Nursing/Allied Health Science, and 11% in Library Sciences. In addition, 20 members listed a health literacy specific title in their signature line. Examples include, Health Literacy: Manger, Consultant, Director, Specialist and Coordinator.

4.1.Understanding the function of the list for members: Types of posts

Categorizing types of posts provided insight into the function of the listserv for members. The results are displayed in Table 3.

Table 3

Types of posts

| Type of post | Number of posts | Percent of posts |

| Announcements | 170 | 8.3% |

| Job postings | 36 | 1.8% |

| Asking/answering questions | 552 | 26.8% |

| Resources | 382 | 18.5% |

| Service | 21 | 1.0% |

| Discussion | 799 | 38.8% |

4.2.Identifying issues of importance to list members: Topics of posts

The authors identified eight “hot topic” areas of substantive importance to list members through our inductive approach. The eight topics of interest described here are: health literacy measurement and assessment, health literacy for public health, health literacy for health professionals, the U.S. Affordable Care Act (ACA) and health insurance, health literacy and equity, and health literacy collaborations. We selected example posts from HLDL to illustrate the diverse points of view associated with each of the topics. These examples were written by subscribers and taken verbatim from the HLDL, they were not edited or written by the authors.

4.2.1.Health literacy measurement and assessment

Health literacy measurement is a recurring topic of interest to members of the listserv. For example, listserv members discussed the use of individual level health literacy measures in clinical settings:

Question: I am reaching out to see if you might recommend a good instrument for assessing health literacy with older adults? We decided against REALM, but are using eHEALS and NVS. We are considering adding the brief health literacy screen. Do you have experience with this measure or alternatives that might work well face-to-face with this population? Thanks so much for any suggestions you can offer.

Response: Most of my research is in underserved rural communities in South Carolina and I have found that most of the research participants cannot use the NVS. Thus, I have found the Single Item screen to provide some measure of health literacy. I am also interested in learning from the experiences others have with the various instruments.

Question: The Joint Commission requires organizations to “perform a learning needs assessment that includes the patient’s cultural and religious beliefs, emotional barriers, desire and motivation to learn, physical or cognitive limitations, and barriers to communication.” Right now my organization includes a box to check for “literacy” in the learning needs assessment but we don’t have a standardized way of determining when a patient/family has literacy barriers. I’m curious to learn if and how other organizations are using the learning needs assessment for health literacy.

Response: My feeling is that time spent on getting valid patient feedback would benefit patients so much more than spending time on trying to figure out which patient goes in which category.

Having coordinated the work on the HLS-EU-Q we are keen to use this instrument, but others may have good experiences, we can learn from. Thanks in advance… .

I am at the HARC conference now, and the folks who just released the data from the PIAAC study are about to share some findings with us. See piaacgateway.org. I believe this is going to be the next version of the NAAL.

I am a research intern … . I am writing my Master’s Thesis

4.2.2.Health literacy for the public

Health literacy interventions outside clinical settings was another prevalent topic of discussion. The listserv moderator initiated an extensive discussion about health education efforts in K-12:

There currently exists a unique opportunity for health literacy advancement in K-12 education. Health literacy instruction in schools has historically been relegated to ancillary programs that are subject to budget cuts. Today, however, schools across the country are adopting the new Common Core State Standards (CCSS) in Math, English and Science. By aligning Health Literacy with CCSS it can become part of CCSS lessons and, as a result, an element of core instruction. We believe firmly that it is much easier to educate children in the concept of Health Literacy than it is to educate adults who typically already have some compromising health issue. Thanks for your interest. I hope others will join us in helping to insure that Health Literacy becomes a key element in CCSS instruction.

Question: I’m working on a developing a family literacy program for English language learners at my library, with a strong health literacy component. As a fan of the IHA’s easy to read health books, I was looking into the IHA’s HELP curriculum: https://www.iha4health.org/our-products/free-materials. I was curious if anyone on the list had experience implementing this curriculum. If so, I would be very interested in hearing how your program operated and any other details you would like to share!

Response: This page is rich in links to information on that may be helpful: http://www.ncsall.net/index.php@id=25.html. The sample lesson plans are very helpful. Also, there was some great work done in University of Illinois at Chicago, I think, on ABE and health literacy, but I can never find the curricula on the web. If anyone has a link, post it!!!! The lesson plans were great. A possible handout for you: http://say-ah.org/wp-content/uploads/SAY-AH-ENGLISH.pdf.

Response: I would be interested in reading the answers to this inquiry. I remember attending an IHA Health Literacy Conference workshop a few years ago, where the speakers shared their experiences and outcomes with using the “What to Do When Your Child Gets Sick” books. Are there published reports on this matter?

Response: KidsHealth.org has a huge amount of content for kids, as well as for teens and for adults on a wide range of medical and behavioral issues – including very basic concepts. It’s in English and in Spanish. There are a number of features that focus on helping family members talk to each other about important health topics.

4.2.3.Health literacy for health professionals

Teaching and training future health professionals was a frequent topic of discussion as members shared materials to create clearly articulated learning objectives as well as tools and techniques to achieve competencies:

We have an undergraduate pre health class for our Interdisciplinary Health Services program. This program is a pre-program for a variety of clinical and non-clinical graduate programs (different elective tracks for each program) but they all take our health literacy class. I am uploading my syllabus as well. We also have an on campus and hybrid version of the class.

This summer I taught ‘fundamentals of health literacy’ to undergraduate pre-health students at the university. I am still working out some of the ‘bugs’ but found that the course was well received. The plan is to offer it annually as an elective. If you have suggestions for improvement, please share them with me.

Please share what anyone is doing for skill development or formal staff education. If you have any data of pre- and post-education that demonstrates results of your efforts in the way of improved patient satisfaction scores or fewer patient complaints centered around communication/education issues, etc. please share.

4.2.4.Affordable Care Act (ACA) and health insurance literacy

Listserv members exchanged information and ideas related to the U.S. Affordable Care Act (ACA) and how to improve health insurance literacy. Given the introduction of the ACA in 2010, it is not surprising we found extensive discussion related to implementation strategies and materials:

Question: We’re putting on our homepage a graphic about the ACA and how time is running out. I’m … concerned about the graphic and the wording. I think we should use the word “fine” or something less harsh than “penalty.” A couple of other individuals who are doing this work, shy away from the word “penalty” because it is so negative – and I want people to make an informed decision, so if they are willing to pay the fine, that is well within their right. Thank you all in advance for your help! We’re going to try to get this up tomorrow.

Response: Some people are calling the penalty a “shared responsibility payment” and some call it a fee. We are calling it a penalty and we give out a worksheet so people can figure what their penalty will be. Do you have a list of assisters & navigators? Telling people where to get that kind of help is good information to be giving out.

Response: You could call it a tax… that what the supreme court called it.

4.2.5.Health literacy and equity

Discussion of health literacy and cultural competency among list members appears to be an evolving topic. A listserv member requested clarification around integrating health literacy and cultural competency in healthcare delivery and training:

Question: We know that health literacy and cultural competence – or cultural sensitivity – are distinct, yet have many overlapping parts. If an organization wants to improve its capacity in both of these areas, how much is the effort integrated and how much is separate? How would you approach this dual challenge and why?

Response: I think cultural competence and health literacy are linked and that they need to be integrated systematically and integrated within all communications and interactions.

Response: I always include culture and language in my health literacy courses and professional development trainings. I used the Primer on Cultural Competency and Health Literacy (2013) to help me identify overlapping competencies and relevant teaching tools. I am really looking forward to teaching this new course… and learning from my students how well the approach works and what changes I will need to make.

… last week our keynote speaker … spoke of the social determinants of health. One of things she was adamant about is that it isn’t “health equality” we should be striving for, but “health equity” – the subtle differences of which I had not truly understood until she explained it during her address…

… I have argued that our health literacy challenge is partially a result of the power and privilege of health industrial complex and how this leads to the oppression of patients. What I would like to see in future months is some discussion around power and privilege in medicine and any research that has examined it and how it impacts the communication flow between the system and patients.

4.2.6.Health literacy collaboration

Health literacy coalitions exist in a number of regions and states in the United States. Members of newly established coalitions post questions asking for support and advice. In response, leaders of established coalitions provide guidance and advice based on their own experience:

I think that a coalition needs to start with a vision, a mission, goals and objectives decided by the members of the coalition. A vision is the big picture of what the ideal world would look like. The mission is a piece of the vision that the coalition wants to address, the goals are the focus of the coalition for a given period of time, and the objectives are the steps or processes to accomplish a goal. Ideally a coalition wants to start focusing on small, concrete goals that can be accomplished and used as models. Once those are accomplished, the coalition can serve more people with the same goal or decide on new goals.

We begin each quarterly membership meeting by going around the room so that all of the

4.2.7.Health literate organizations and interventions in healthcare

Numerous discussions centered on health literacy interventions in healthcare and clinical settings, and the concept of a health literate organization. Listserv members requested and exchanged information as well as offered to discuss interventions and available resources offline with others:

Request: I am brainstorming for Health Literacy Month at my organization, and I would love to hear about the successes that you have had in the past especially when it comes to events/programs geared towards clinical staff. We are planning to do some tabling and set up some passive displays but it would be great to engage staff in other ways. If you have ideas or experiences around this I (and presumably others!) would love to hear them.

Response: I just completed a project on this [signage] in primary care clinics. You can contact me directly if you would like to discuss. I used photography as a tool to explain to stakeholders and leaders what makes good signage, and what doesn’t, after an in-depth assessment.

Response: Building Health Literate Organizations: A Guidebook to Achieving Organizational Change describes how organizations can move forward in achieving the attributes described in the Institute of Medicine discussion paper, “Ten Attributes of Health Literate Health Care Organizations”. The guidebook offers an approach that enables organizations to start where they can begin to build a pattern of success, expanding to more than one area, eventually working in all key areas for results that can be sustained.

Response: We do not include it [teach back] in our policy as making policies too prescriptive opens brings the potential for liability and Joint Commission penalty if the policy is not followed 100% of the time. Teach back is taught and its use encouraged. It is documented in the patient education section of the EHR.

4.2.8.Plain language health information

Listserv members frequently requested guidelines and information to develop materials in plain language and received invaluable expertise and exchange of resources:

Question: Does anyone know of any reasons why questions should or should not be used as headers/subheads in communications to the member/lay audience? I’m specifically looking for any guidelines, studies, or other evidence (e.g., expert opinions) that provide reasons either for or against this practice.

Response: Here is an article she wrote for PLAIN (Federal). It doesn’t address headings as questions specifically but does say people like headings.

Question: The persons at the facilities with whom we are working have asked us to use very basic patient education materials due to the many factors that we know this population faces. Although we have education on all these topics, even 6th–8th grade level literacy seems too high. Any suggestion of where to look for materials?

Response: Some of the sources I go to for some of the best clear, basic descriptions of medical conditions are through sources that have information in multiple languages. Some of these can be most easily found on MedlinePlus on their “Health Information in Multiple Languages” link. You can see they also have an “Easy-to-Read Materials” link, but those are not always 6th–8th grade.

Question: What are your thoughts on the best readability tool? Is there a HL industry standard? I have been trained in many of them and can’t figure out which one is best.

Response: I suggest you look at CMS’ Toolkit on Making Written Material Clear and Effective, Part 7: Using readability formulas: A cautionary note (https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Outreach/WrittenMaterialsToolkit/ToolkitPart07.html). Also look at tools that measure understandability and actionability, e.g., AHRQ’s Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT – www.ahrq.gov/pemat) and CDC’s Clear Communication Index (www.cdc.gov/ccindex/).

5.Discussion

This study describes how subscribers to the Health Literacy Discussion List (HLDL) use the service and what topics of discussion are of interest. The findings add to a growing body of literature that uses electronic discussion lists as a setting and corpus for research.

Among the study’s limitations, the study’s findings reflect only the assessed two-year time frame – from October 2013 to October 2015. The findings are limited to the activities of involved HLDL subscribers. The findings may or may not apply to subscribers who receive but do not interact with the listserv. The authors acknowledge a potential for selection bias since we are health literacy practitioners and were involved in HLDL activities during the study’s assessed time period. Conversely, the authors’ knowledge, experience, and involvement in HLDL and health literacy practice may have helped detect patterns in subscriber use.

In terms of basic use, the results suggest HLDL supports health literacy professionals by raising diverse topics and providing peer-generated feedback. Among its peer services, the HLDL: asks and answers questions; shares information and resources; provides technical assistance; and is a platform for professional discourse. The authors found subscribers use the list for: announcements; asking and answering questions; sharing resources; and discussion.

The majority of announcements are to promote professional development opportunities including conferences and online trainings. Subscribers also seek feedback, such as technical assistance regarding intervention approaches as well as sharing professional and consumer resources. Subscribers who are most inclined to use the list as a feedback resource, seem to be students or practitioners who are in the nascent stage of a health literacy job or career. These findings are consistent with other studies of how health and non-health professionals use a peer, subscriber listserv [1,2,6,7,10,11,13,17].

In terms of subscriber background, while some email lists serve subscribers with similar professional training, HLDL’s members are professionally diverse. Nurses, librarians, and public health professionals all subscribe and use the HLDL.

By analyzing the listserv’s signature lines, the authors found subscribers also represent an array of 20 job titles that include the words ‘health literacy,’ including Health Literacy Manager and Health Literacy Coordinator.

Interestingly, some subscribers described that professional isolation is an operant challenge for some health literacy practitioners around the world. For example, one subscriber posted: “I’m the only one in my workplace who is advocating for health literacy.” Apparently for these and other subscribers, the HLDL is a place where health literacy practitioners create a sense of community and peer support. Some other specific health literacy issues discussed within the HLDL include: health literacy research and assessment; how the U.S. Affordable Care Act and health insurance impact health literacy; health literacy interventions in healthcare settings; peer coalition building; providing or finding plain language health information; and the training of health literacy and other health professionals [2].

In contrast, with one exception there was little interaction among HLDL subscribers regarding contemporary health information technological (HIT) issues, such as the use of social media to improve public access to health information and services as well as HIT interventions to improve health outcomes. Yet, HLDL subscribers discussed their experiences with electronic medical records (EMRs). Subscribers asked questions, shared resources, and discussed the implications of integrating a health literacy measure within patient EMRs.

In addition, some subscribers used the HLDL for what the authors term ‘service to the field.’ In these cases, subscribers would ask peers to take action in some way, or formally share their expertise in a survey. In one case, subscribers were asked to review the new design of a U.S. government website and provide feedback. In another case, subscribers were asked to advocate for the inclusion of health literacy questions in the U.S. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey and to give feedback on a set of draft questions. Another small, but noteworthy, use of the list is to post health literacy job announcements.

The findings additionally suggest subscribers appreciated the role and presence of HLDL’s moderator. The study suggests subscribers value the ability of a moderator to facilitate peer discussion. The positive influence of the list moderator to generate discussion and engage subscribers is consistent with previous research [17].

The current research contributes to the growing literature on electronic discussion lists (listservs) as a setting for research. The study’s methods include the use of an independent coding tool to assess the face validity of researcher-derived findings.

Finally, the study suggests electronic data can be a data corpus for researchers who wish to assess the content of electronic mediated communication. The current research describes the specific listserv use of some health literacy practitioners and suggests the importance of online discussions about research and practice within a professional community.

6.Implications

The authors suggest three broader implications of the HLDL for health literacy knowledge and practice: as an information repository, as a site for professional development, and as a forum for identifying needs and solutions prior to discourse at professional meetings and in publications.

First, the HLDL serves as an information repository for the field of health literacy. As pointed out, listserv members did not use the web-based version of the list for approximately two years. The change from an email listserv to a web-based system from 2011 to early 2013 resulted in a loss of professional discourse. To develop and maintain a corpus of professional thought, it is critical to have a communication system such as the HLDL the health literacy community of practice will use.

Second, the list serves the field as a site for peer to peer professional development and support. Similar to other professional listservs, the HLDL serves as a means to request information and share best practices. The HLDL is especially important to the development and socialization of new professionals and students. Long term subscribers share institutional knowledge of the field, while new subscribers ask for insights about ideas and practices.

Third, the HLDL is a forum where new topics and challenges (such as the adoption of electronic medical records) are discussed before they appear at conferences or in professional papers. During the early iterations of analysis, the authors also identified information communication technologies (ICTs) such as mobile app, webinars, chat, and social media as topics of discussion. The proliferation of ICTs highlight a need and opportunity not fully realized to utilize new technologies and ICTs to leverage and enhance health literacy practice.

7.Conclusions

Electronic discussion lists are a valuable mechanism for professional discourse and development. Content analysis of the HLDL suggests that a diverse group of professionals interested in health literacy use the list to make announcements, ask and answer questions, share information and resources, and discuss practical and conceptual issues.

Topics of discussion largely mirror those reflective of the time period and include “hot topics” such as assessment and measurement, the U.S. Affordable Care Act, and creating health literate organizations. List members also addressed topics that are not yet being addressed in research or publications but warrant more immediate outlets for discussion because they are already confronted in practice. Examples include electronic medical records and a growing interest in exploring the relationship between health literacy, equity, and social justice. The list and its members serve as a source for expertise and input on issues that affect the field as a whole, and a corpus for research and tracking emerging concepts that will shape development of health literacy study and practice.

References

[1] | J. Bar-Ilan and B. Assouline, A content analysis of PUBYAC – A preliminary study, Information Technology and Libraries 16: ((1997) ), 165–174. |

[2] | C.A. Christie and T. Azzam, What’s all the talk about? Examining EVALTALK, an evaluation listserv, Am. J. Eval. 25: (2) ((2004) ), 219–234. doi:10.1177/109821400402500206. |

[3] | J. Cohen, Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit, Psychol. Bull. 70: (4) ((1968) ), 213–220. doi:10.1037/h0026256. |

[4] | J.L. Fleiss and J. Cohen, The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability, Educ. Psychol. Meas. 33: (3) ((1973) ), 613–619. |

[5] | B. Glaser and A. Strauss, The Discovery Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Inquiry, Aldin, Chicago, IL, (1967) . |

[6] | N. Hara and K.F. Hew, Knowledge-sharing in an online community of healthcare professionals, Information Technology & People 20: (3) ((2007) ), 235–261. doi:10.1108/09593840710822859. |

[7] | S. Irvine-Smith, A series of encounters: The information behaviour of participants in a subject-based electronic discussion list, J. Info. Know. Mgmt. 9: (3) ((2010) ), 183–201. doi:10.1142/S0219649210002619. |

[8] | J.R. Landis and G.G. Koch, The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data, Biometrics 33: (1) ((1977) ), 159–174. doi:10.2307/2529310. |

[9] | Y.S. Lincoln and E.G. Guba, Naturalistic Inquiry, Sage, Newbury Park, CA, (1985) . |

[10] | P.F. Marty and N.D. Alemanne, Engaging the experts in museum computing: Seven years of queries on MCN-L, Curator 56: (4) ((2013) ), 421–433. doi:10.1111/cura.12042. |

[11] | E. Neukrug, R. Cicchetti, J. Forman, N. Kyser, R. McBride and S. Wisinger, A content analysis of CESNET-L e-mail messages: Directions for information delivery in higher education, J. Comput. High. Educ. 22: (1) ((2010) ), 60–72. doi:10.1007/s12528-010-9029-0. |

[12] | L. Nielsen-Bohlman, A.M. Panzer and D.A. Kindig, Health Literacy: A Prescription to End Confusion, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC, (2004) . |

[13] | T. Pennington, C. Wilkinson and J. Vance, Physical educators online: What is on the minds of teachers in the trenches?, Physical Educator 61: (1) ((2004) ), 45–56. |

[14] | R. Rudd, I. Kirsch and K. Yamamoto, Literacy and health in America, Policy Information Report, Educational Testing Service, Princeton, NJ, 2004. |

[15] | Scientific Software Development GmbH, ATLAS.ti Version 7, Berlin, 2015. |

[16] | E. Vaast and G. Walsham, Grounded theorizing for electronically mediated social contexts, Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 22: (1) ((2013) ), 9–25. doi:10.1057/ejis.2011.26. |

[17] | B.M. Wildemuth, L. Crenshaw, W. Jenniches and J.C. Harmes, What’s everybody talking about?: Message functions and topics on electronic lists and newsgroups in information and library science, J. Educ. Libr. Inf. Sci. 38: (2) ((1997) ), 137–156. doi:10.2307/40324217. |

[18] | World Education, Health literacy: New field, new opportunities, Boston, MA, 2004, http://www.healthliteracy.worlded.org/docs/tutorial/SWF/flashcheck/main.htm. |