Effective remote teaching: Transitioning small group teaching online

Submitted: 23 July 2020

Accepted: 21 October 2020

Published online: 13 July, TAPS 2021, 6(3), 121-123

https://doi.org/10.29060/TAPS.2021-6-3/CS2361

Sandra E Carr, Katrine Nehyba & Bríd Phillips

Division of Health Professions Education, School of Allied Health, The University of Western Australia, Australia

I. INTRODUCTION

COVID-19 has caused a major disruption to medical education with many educators making rapid shifts to online teaching (Sandars et al., 2020). Many have had to make critical changes in their instructional delivery (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020; Perkins et al., 2020). These changes may have lasting effects on the shape of educational delivery impacting generations to come (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020). It is important to share these changes and innovations as “Students and educators can help document and analyse the effects of current changes to learn and apply new principles and practices to the future” (Rose, 2020, p. 2132). Our case study examined the transition of small group teaching from blended learning to an emergency remote teaching environment.

II. CONTEXT

At the University of Western Australia, medical students undertake a scholarly activity during the third and final years of their Doctor of Medicine that enables specialisations in research or coursework. Of these students, 27% (n=65) choose a specialisation in Medical Education and graduate having completed 75% of a graduate certificate in health professions education. The first unit, Principles of Teaching and Learning offers an introduction to educational theory, curriculum design, teaching and assessment with a focus on developing teaching skills in small and large group settings and applies blended learning strategies. The final assignment assesses small group teaching techniques and the application of peer assisted learning and feedback. This group assignment requires students to:

a. Develop, plan and deliver a face to face small group teaching activity.

b. Describe and assess the group work processes using an audio journal and group assessment rating.

c. Engage in Peer Observation of Teaching.

With the advent of COVID-19 a change in the assessment was required. The 65 students were informed that the group work would have to occur on line and the small group teaching activity would now be an online Video Presentation. Within the Blackboard learning management system, each group had access to a Discussion Board and a virtual meeting tool to support collaboration and teamwork. The marking rubric was not adjusted so the focus on application of small group teaching techniques remained. The video of the developed small group teaching activity was uploaded along with the audio journal and peer observation of teaching components of the assessment.

III. STUDENT EXPERIENCE

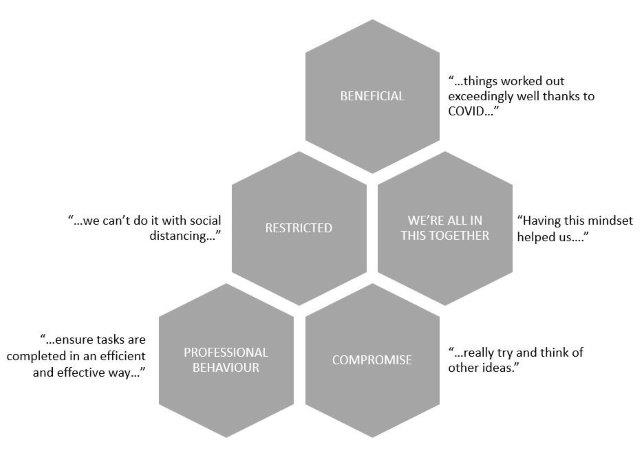

We undertook a thematic analysis of students’ audio journals and written responses to describe their experience in five broad themes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Student experiences of an online group assignment

Thirty percent of students reported aspects of working online as beneficial, and in some ways an improvement on face-to-face contact. For example, students who otherwise could have experienced difficulty meeting in person were able communicate and meet more easily:

“…we have already managed to organise our first meeting quite swiftly and with ease…”

(S1)

They also reported learning new skills:

“This group project taught me valuable skills when working in an online environment, including how to utilise and contribute in video meetings, share resources and regularly update the group…”

(S25)

“I have also learnt that filming or video is a great medium to communicate messages…once it is done, it can be a very effective tool.”

(S5)

However, not unexpectedly, some of the changes were seen as restrictions. The students talked of being “…banned from entering the hospital…” and of “…having no access…” to equipment or rooms, and “…we can’t do it with social distancing…” This led to feelings of disappointment and frustration, as they tried to find feasible options for the assignment.

“…all four of us were trying to actively brainstorm for an hour, trying to think of something…”

(S60)

“…we had fantastic plans…but unfortunately we didn’t have any of these options…”

(S25)

The perceived restrictions challenged the students’ persistence and adaptability (Ferrel & Ryan, 2020) and led them to compromise. One student, after their group changed their assignment idea from venepuncture to handwashing, said “…we…decided to try and make this idea work the best we could.” (S18). This adjustment and negotiation of ideas led to some innovative and varied submissions, using, for example, dolls; online role-plays; on-screen debate and custom virtual backgrounds.

Another theme that emerged was that of a shared experience, and a sense of we’re all in this together. The use of online communication platforms such as Zoom and Facebook Chat, and the use of shared documents meant that “…everyone could be involved, regardless…” There was evidence of a supportive environment and shared accountability, to ensure that they were “…giving everyone a chance…” and “…everyone seemed equally invested…”

Finally, despite the changes, restrictions and compromise, the students remained task-focussed and were able to plan, allocate, collaborate and communicate in their new online environment. The spread of grades for this assignment was consistent with previous cohorts, suggesting that the change in method was not detrimental to their performance. They were aware of potential dangers of working in this new, unknown way.

“…it will be important for us to be mindful of the risk of losing a professional mindset during our meetings, and divert away from the task at hand.”

(S1)

However, they described the same professional behaviours that would be expected in a face-to-face assignment, such as planning; delegation; effective communication; setting and meeting deadlines; and providing constructive feedback to other team members.

“…our team worked really well together. I suspect things worked out exceedingly well thanks to COVID and lockdown, which forced us to work online.”

(S8)

IV. CONCLUSION

Sklar states that during these unprecedented times “…it is important that our voices are loud about what we have experienced and learned” (Sklar, 2020, p. 9). In this case study we have described an experience of emergency remote teaching, in which a face-to-face small group teaching assignment was moved online. Our experience suggests that, even with its challenges, it was a success. Despite restrictions and compromise the students reported beneficial aspects to working online, and demonstrated a sense of comradery and professionalism while developing digital learning skills that are proving essential for learners and applicable for health professionals in the 21st century.

Notes on Contributors

Sandra Carr conceived the idea of the case study and contributed to the design of the work, gathered the qualitative data and interpretation of the findings. Katrine Nehyba contributed to the design of the case study, searched the supporting and relevant literature, undertook the thematic analysis of the data and constructed the Figure. Bríd Phillips contributed to the design of the work, searched the supporting and relevant literature to construct the rationale and introduction and contributed to the interpretation of the findings. All contributed to confirmation of the themes, the Discussion and Conclusion. All reviewed and contributed to each draft of the paper and approval the final submission.

Acknowledgement

This project was subject to ethical approval by the human ethics committee of the University of Western Australia. Consent was waived in line with the ethical approval obtained.

Funding

This work has not received any external funding.

Declaration of Interest

All authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

References

Ferrel, M., & Ryan, J. (2020). The Impact of COVID-19 on Medical Education. Curēus, 12(3), e7492–e7492. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Perkins, A., Kelly, S., Dumbleton, H., & Whitfield, S. (2020). Pandemic pupils: COVID-19 and the impact on student paramedics. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 17(1), 1-4. https://doi.org/10.33151/ajp.17.811

Rose, S. (2020). Medical student education in the time of COVID-19. Journal of the American Medical Association, 323(21), 2131–2132. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5227

Sandars, J., Correia, R., Dankbaar, M., de Jong, P., Goh, P., Hege, I., Masters, K., Oh, S., Patel, R., Premkumar, K., Webb, A., & Pusic, M. (2020). Twelve tips for rapidly migrating to online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. MedEdPublish, 9(1), 82. https://doi.org/10.15694/mep.2020.000082.1

Sklar, D. (2020). COVID-19: Lessons from the disaster that can improve health professions education. Academic Medicine, 95(11), 1631–1633. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003547

*Sandra Carr

Division of Health Professions Education

The University of Western Australia

35 Stirling Hwy,

Crawley WA 6009, Australia

Tel: +61 64886892

Email: Sandra.carr@uwa.edu.au

Announcements

- Fourth Thematic Issue: Call for Submissions

The Asia Pacific Scholar is now calling for submissions for its Fourth Thematic Publication on “Developing a Holistic Healthcare Practitioner for a Sustainable Future”!

The Guest Editors for this Thematic Issue are A/Prof Marcus Henning and Adj A/Prof Mabel Yap. For more information on paper submissions, check out here! - Best Reviewer Awards 2023

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2023.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2023

The Most Accessed Article of 2023 goes to Small, sustainable, steps to success as a scholar in Health Professions Education – Micro (macro and meta) matters.

Congratulations, A/Prof Goh Poh-Sun & Dr Elisabeth Schlegel! - Best Article Award 2023

The Best Article Award of 2023 goes to Increasing the value of Community-Based Education through Interprofessional Education.

Congratulations, Dr Tri Nur Kristina and co-authors! - Volume 9 Number 1 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2022

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2022.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2022

The Most Accessed Article of 2022 goes to An urgent need to teach complexity science to health science students.

Congratulations, Dr Bhuvan KC and Dr Ravi Shankar. - Best Article Award 2022

The Best Article Award of 2022 goes to From clinician to educator: A scoping review of professional identity and the influence of impostor phenomenon.

Congratulations, Ms Freeman and co-authors. - Volume 8 Number 3 of TAPS is out now! Click on the Current Issue to view our digital edition.

- Best Reviewer Awards 2021

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2021.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2021

The Most Accessed Article of 2021 goes to Professional identity formation-oriented mentoring technique as a method to improve self-regulated learning: A mixed-method study.

Congratulations, Assoc/Prof Matsuyama and co-authors. - Best Reviewer Awards 2020

TAPS would like to express gratitude and thanks to an extraordinary group of reviewers who are awarded the Best Reviewer Awards for 2020.

Refer here for the list of recipients. - Most Accessed Article 2020

The Most Accessed Article of 2020 goes to Inter-related issues that impact motivation in biomedical sciences graduate education. Congratulations, Dr Chen Zhi Xiong and co-authors.