The Impact of Preeclampsia on Work-Related Psychosocial Aspects and Need for Recovery

*Corresponding Author(s):

Muijsers HECDepartment Of Cardiology, Radboud University Medical Center, Geert-Grooteplein Zuid 10, 6525 GA, Nijmegen, Netherlands

Tel:+31 243616785,

Email:hella.muijsers@radboudumc.nl

Abstract

Objective: Women with a history of preeclampsia and/or Hemolysis Elevated Liver enzymes Low Platelets (HELLP) syndrome report impaired cognitive functioning, such as concentration problems and decreased memory function. The presence of subjective cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms and cognitive deficits may affect working abilities. Data on work-related psychosocial aspects and need for recovery after a pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia/HELLP are lacking. We assess whether work-related aspects, need for recovery, and recovery opportunities are altered in women with a history of preeclampsia/HELLP.

Methods: Online questionnaires were administered to members of the Dutch HELLP Foundation to collect data on medical and obstetric history and on work-related psychosocial aspects, need for recovery and recovery opportunities. The latter were measured using the short Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ-II), the work-related need for recovery scale and the recovery opportunities scale.

Results: A total of 137 women with a mean (SD) age of 36 (5.8) years completed the questionnaire. Participation occurred a median of 3 years after the index pregnancy, which had a mean gestational age at delivery of 34 weeks and 2 days. Participating women scored remarkably poor on psychosocial work aspects, such as work pace, self-rated health, and risk of burn-out. Quantitative demands, influence at work, work-family conflicts, and mental stress were domains requiring attention as well. Furthermore, 106 women showed a high work-related need for recovery.

Conclusion: Work-related aspects are affected by previous preeclampsia/HELLP, especially work pace, quantitative demands, influence at work and work-related need for recovery.

Keywords

HELLP syndrome; Preeclampsia; Work-related need for recovery; Work-related psychosocial aspects; Work-related recovery opportunities

Introduction

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are severe pregnancy complications, leading to both short- and long-term consequences. The most severe hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, preeclampsia, is a major cause of maternal morbidity and mortality and affects 3-5% of all pregnancies [1]. Preeclampsia can be further complicated by Hemolysis Elevated Liver enzymes Low Platelets (HELLP) syndrome [2], which occurs in 0.2-0.8% of all pregnancies [3]. Preeclampsia is an important and internationally recognized female-specific cardiovascular risk factor, leading to a fourfold elevated risk of hypertension and a twofold higher risk of cardiovascular disease at younger age [4]. Preeclampsia is also associated with an elevated risk of developing dementia, in particular vascular dementia, possibly due to on-going endothelial dysfunction and inflammation [5].

Preeclampsia/HELLP is considered to be a serious life-event and can understandably lead to psychosocial distress. Previously affected women consistently report impaired cognitive functioning, varying from attention deficits, concentration problems, and decreased short- and long-term memory function in the years following the complicated pregnancy [6,7]. Although preeclampsia is associated with subjective cognitive impairment, no objective differences on neurocognitive tests could be demonstrated in a systematic review [8]. It is postulated that complaints of cognitive failure are most probably a reflection of neurocognitive dysfunction in complex, stressful daily-life situations [9]. The presence of subjective cognitive impairment, perhaps enhanced by depressive symptoms [10], may affect return to work and executive functioning at work. Only a few studies investigated the psychosocial impact of preeclampsia on return to work after the index pregnancy [11-13]. Rep et al., [11] showed that in addition to the psychological effects of preeclampsia/HELLP, some women did not resume work at all due to sick leave (9%) or health problems (7%). Similar results were found by Gaugler-Senden et al., [13]. In a study by Poel et al., [12], the number of women not resuming work after a pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia/HELLP was even higher, as 23% did not return due to sick leave and 14% stopped working due to health problems.

For women resuming work after such complicated pregnancies, there is no evidence regarding work-related psychosocial aspects and stress thus far. As a result, recognition of problems and professional support when problems occur is lacking. A higher need for recovery after work is a major symptom of chronic work-related stress and risk of burn-out [14]. If opportunities to recover from work efforts are insufficient [15], the employee will start the next working day with a residual need for recovery. This cumulative process can lead to burnout [14]. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to investigate the impact of preeclampsia/HELLP on work-related psychosocial aspects, need for recovery, and recovery opportunities, and to identify women at the highest risk of developing work-related stress.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The study population consisted of members of the Dutch HELLP Foundation (‘HELLP Stichting’; https://www.hellp.nl/). All members previously experienced preeclampsia and/or HELLP syndrome. Involvement in this community is voluntary with a small entry donation for membership. All members were invited to participate in an online questionnaire that was posted on the HELLP Foundation website in February 2017. Attention was created on the website and related social media. A waiver was provided by the Regional Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects Arnhem-Nijmegen, The Netherlands, since medical-ethical approval was not required for this questionnaire. The results were reported according to the STROBE checklist [16].

Instruments

The questionnaire developed for this study consisted of questions on general health, medical and obstetric history, and general occupational activity. Work-related psychosocial aspects, need for recovery, and recovery opportunities were measured using the short Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire [17], the need for recovery scale [14] and the recovery opportunities scale [15].

Work-related psychosocial aspects

Work-related psychosocial aspects were measured using the short Dutch version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire (COPSOQ-II) [17], consisting of 36 items grouped into 19 different scales that covered five psychosocial domains: demands at work, work organization, interpersonal relationships and leadership, values at workplace, and health and well-being. We measured the following psychosocial working conditions using the 19 different scales: quantitative demands, work pace, emotional demands, influence at work, possibilities for development, meaning of work, commitment to the workplace, predictability, rewards, role clarity, quality of leadership, social support, job satisfaction, work-family conflict, vertical trust, justice and respect, self-rated health, risk of burn-out and work-related stress.

The validation of this questionnaire was described elsewhere [17]. The internal consistency determined using Cronbach alpha was 0.872. Each scale is a composite of two items and has a theoretical range of 0-100. Most questions have five response options, ranging from ‘always’ or ‘to a very large extent’ to ‘never’ or ‘to a very small extent’. The answers were transformed to a value ranging from 0 to 100 points. Scale scores were computed as the average of the values of single items. The cut-off values above or below which scores are labelled problematic or needing attention differ among the various scales.

Need for recovery

The work-related need for recovery scale is a scale to measure symptoms of fatigue at work, consisting of 11 items, each with a 2-point frequency scale (0 = no, 1 = yes). Therefore, the possible score ranged from 0 to 11. This scale was transformed to a range between 0 (minimum) and 100 (maximum) for analysis of the data. At individual level, a cut-off of 54.5 or higher indicates an elevated need for recovery, requiring intervention [18]. This is an adequate and validated scale for early symptoms of fatigue at work [14,19].

Recovery opportunities

The opportunities to recover from work efforts and diminishing load effects were determined using the recovery opportunities scale. This scale consists of 9 items, each with four answering categories, which are: always, often, sometimes and never [15]. As these answers are scored 0 to 3 points, the maximum possible score on the recovery opportunities scale is 27. A score of 19 or higher suggests a paucity of work-related recovery opportunities. The recovery opportunities scale has good reliability and validity [15].

Statistical analysis

For all continuous baseline characteristics normality was evaluated using skewness and kurtosis. Normally distributed data were expressed as means with Standard Deviation (SD), while non-normally distributed data were expressed as medians with the minimum to maximum range (range). Categorical data are shown as absolute values and percentages. To explore which women are at the highest risk of developing work-related stress, women with elevated scores on the need for recovery scale and the recovery opportunities scale were identified and compared to the other study participants. Differences between groups were tested using independent samples t-tests or Mann-Whitney-U tests, whichever was appropriate. All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Version 25.0, while Graphpad Prism Version 5.03 was used to create graphs.

Results

A total of 211 women opened the online questionnaire and 182 women started answering questions, of which 137 women completed all questions (75%). The highest loss of participants was at the COPSOQ-II questionnaire, which was not completed by 31 women, of which 13 (42%) were unemployed. Only the fully completed online questionnaires were included in the analyses. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the study population. The mean age (SD) of the participants at time of participation was 36 (5.8) years. Participation occurred a median of 3 years after the index pregnancy. Most women experienced two pregnancies and had at least one living child. Women recalled their index pregnancy most often as a combined preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome (80%). Of the remaining women, 20 women recalled having had preeclampsia only (15%), while only 7 women had an isolated HELLP syndrome without hypertension (5%). The mean gestational age of the index pregnancy at delivery was 34 weeks and 2 days, with a corresponding lower mean (SD) birth weight of 2128 (874) grams.

|

Continuous variables (mean ± SD) |

|

|

Age |

35.6 (5.8) |

|

Age at index pregnancy |

30.1 (4.3) |

|

GA index pregnancy (weeks) |

34.3 (3.4) |

|

Birth weight index pregnancy (gram) |

2128 (874) |

|

Continuous variables (median and min-max range) |

|

|

Years post index pregnancy |

3 (0-27) |

|

Number of pregnancies |

2 (1-5) |

|

Dichotomous variables (numbers and percentages) |

|

|

Diabetes mellitus |

2 (1.5) |

|

Pre-existing hypertension |

3 (2.2) |

|

Current hypertension |

14 (10.2) |

|

Preeclampsia/HELLP in first completed pregnancy |

121 (88.3) |

|

Early-onset preeclampsia/HELLP (< 34 weeks) |

56 (40.9) |

|

Preeclampsia |

20 (14.6) |

|

HELLP syndrome |

7 (5.1) |

|

Combined preeclampsia/HELLP |

110 (80.3) |

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of the study participants (n = 137).

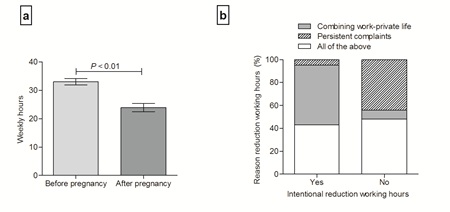

Three women (2%) had pre-existing hypertension and only 14 women (10%) were diagnosed with hypertension after pregnancy or were using antihypertensive medication. For almost 30% of the participating women, the index pregnancy was the sole reason to decide not to have a subsequent pregnancy. Another 50% feared a new pregnancy, but the desire to have more children dominated eventually. Only 11 women (8%) reported to have recovered fully after pregnancy, while 49 women (36%) indicated to have recovered partly. However, over half of the women (56%) did not recover at all after the index pregnancy. Table 2 shows occupational characteristics of the study participants. All women worked before pregnancy, for an average of 33 hours per week. After pregnancy, 74% resumed work, 26 women (19%) were on sick leave or reintegrating, and 10 women (7%) were not capable of working anymore. Most women reduced the number of working hours after pregnancy. As shown in figure 1a, this difference in weekly working hours before and after pregnancy was statistically significant. The main reason for intentional reduction of working hours was to combine work and private life. However, 39 women (29%) did not intend to reduce their occupational activities after pregnancy. For 22 of these women (16%), the only reason for the unintended reduction was persisting physical or mental symptoms (Figure 1b).

|

Continuous variables (mean ± SD) |

|

|

Weekly working hours before pregnancy |

33.1 (6.9) |

|

Weekly working hours after pregnancy |

24.0 (8.6) |

|

Reduction in weekly working hours |

-9.1 (8.6) |

|

Categorical variables (numbers and percentages) |

|

|

Current work status |

|

|

Employed |

128 (93.4) |

|

Unemployed |

9 (6.6) |

|

Incapacitated for work |

|

|

No |

101 (73.7) |

|

Sick leave/reintegrating |

26 (19.0) |

|

Yes |

10 (7.3) |

|

Intentional reduction of working hours |

86 (62.8) |

|

Non-intentional reduction of working hours |

39 (28.5) |

|

Received mental support |

71 (51.8) |

|

Provider of household income |

|

|

Participant main provider |

16 (11.7) |

|

Partner main provider |

51 (37.2) |

|

Both provide equally |

70 (51.1) |

|

Marital status |

|

|

Single |

6 (4.4) |

|

Married or cohabiting |

131 (95.6) |

|

Highest completed education |

|

|

Secondary education |

53 (38.7) |

|

Tertiary education (bachelor or higher) |

84 (61.3) |

Table 2: Occupational characteristics of the study participants (n =137).

Figure 1: Panel a: weekly working hours before and after pregnancy. Results are shown as means with 95% confidence interval. Panel b: Motivation to reduce weekly working hours comparing intentional versus non-intentional reduction.

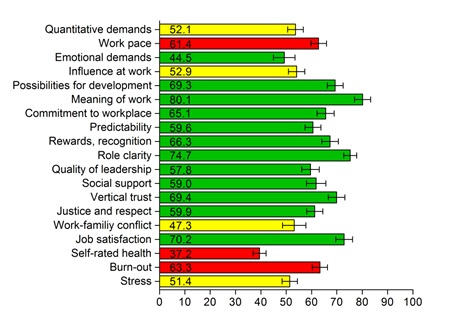

Over half of the women (52%) indicated to have received mental support by a psychologist or social worker after the index pregnancy. Most participants were married or cohabiting, provided equally to the household income, and participants were relatively highly educated. Figure 2 shows the mean scores on the different COPSOQ-II scales. The exact 95% confidence intervals for all scales are shown in the supplemental table. Problems among the women in this study were mostly seen in the domains demands at work, and health and well-being. Women with a history of preeclampsia/HELLP scored remarkably poor on work pace, self-rated health and burn-out. For work pace and burn-out a score of 55 or higher is elevated and acknowledged as problematic, for self-rated health a score of 45 or lower is problematic. Quantitative demands, influence at work, work-family conflict and stress were domains requiring attention as well. The scales quantitative demands, work-family conflict and stress are favorable with a score below 45 and problematic above 55, for influence at work the score is reversed.

Figure 2: Results from the COPSOQ II questionnaire. Results are shown as mean (numbers) with 95% confidence intervals. The colors indicate whether results are favorable (green), problematic (red), or doubtful requesting further attention (yellow).

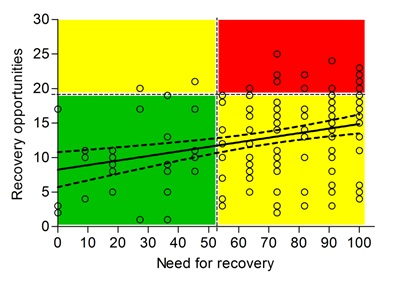

Figure 3 illustrates the scores on the scales for work-related need for recovery and recovery opportunities. Strikingly, 106 women (77%) showed signs of work-related need for recovery, with a mean (SD) score of 69.7 (27.1). Most of these women had enough opportunities to recover from work, with a mean (SD) score of 12.9 (5.7). However, 19 women (14%) scored high on both the work-related need for recovery scale and the recovery opportunities scale. These women were statistically significant younger than women in the green and/or yellow zones (mean age (SD) 32.1 (5.2) versus 36.1 (5.7) years, respectively; P=0.004) and all experienced preeclampsia/HELLP in their first pregnancy. In addition, they seemed to have reduced their weekly working hours unintentionally more often (42% versus 26%, P=0.16) and to a greater extent (mean reduction in hours (SD) -12.3 (10.4) versus -8.8 (8.2), P=0.09). On the COPSOQ-II questionnaire these women scored statistically significant worse on demands at work (work pace and emotional demands) and influence at work.

Figure 3: Linear regression analysis of the association between need for recovery and recovery opportunities. A score of 54.5 or higher for need for recovery is elevated and indicates that intervention is required. For recovery opportunities a score of 19 or higher is elevated, demonstrating a lack of possibilities to recuperate. The colors indicate whether the results are favorable (green), only one of the two scores is elevated (yellow), or scores on both scales are elevated (red).

Figure 3: Linear regression analysis of the association between need for recovery and recovery opportunities. A score of 54.5 or higher for need for recovery is elevated and indicates that intervention is required. For recovery opportunities a score of 19 or higher is elevated, demonstrating a lack of possibilities to recuperate. The colors indicate whether the results are favorable (green), only one of the two scores is elevated (yellow), or scores on both scales are elevated (red).

Discussion

In this study, work-related psychosocial aspects were importantly affected by a prior pregnancy complicated by preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome, especially work pace, quantitative demands and influence at work, leading to stress-related problems and reduction in working hours. The psychosocial impact of preeclampsia/HELLP is high, especially in the first few years after the index pregnancy. Our results showed that 73% of the women resumed work, but 26 women (19%) were still on sick leave and 10 women (7%) were not capable of working anymore, which is comparable to existing evidence [11,13]. In this study, we showed that women with a history of preeclampsia/HELLP scored poor on work pace, self-rated health and burn-out measures. In addition, attention seems to be required for quantitative demands, influence at work, work-family conflict and stress. In previous research, the COPSOQ questionnaires showed to be a potent predictor of self-reported health, mental health and work-related outcome [20,21].

Especially demands at work, such as work pace, quantitative demands, and work-family conflict were altered, which could suggest impaired executive functioning. Fields et al., [22] showed that women with a history of preeclampsia had impaired executive functioning, verbal learning and attention. These cognitive changes were consistent with changes observed in vascular disease and cerebral white matter lesions [22]. In the general population, cerebral white matter lesions are associated with cognitive decline and predict an increased risk of stroke, dementia and death [23]. Imaging studies showed that women with a history of preeclampsia more often have cerebral white matter lesions compared to women who have had a normotensive pregnancy, within the first few years after the complicated pregnancy as well as decades later [24-26]. However, these lesions have not been associated with cognitive impairment after preeclampsia thus far [27]. It could be postulated that the elevated risk of developing white matter lesions and vascular dementia after preeclampsia/HELLP is the result of cardiovascular risk factors, such as hypertension [5]. Recent research showed that the elevated cardiovascular risk after preeclampsia/HELLP is largely mediated by the development of chronic hypertension [28].

Notably, 106 women showed signs of work-related need for recovery implicating fatigue at work, which might indicate chronic work-related stress. Beside the elevated cardiovascular risk after preeclampsia/HELLP, both psychosocial factors [29] and a high need for recovery [30] are linked to cardiovascular disease and high blood pressure, probably mediated through neuroendocrine activation after work [31]. Plausibly, women encountering problems in execution of work and recovery from their work may profit from early recognition to prevent burn-out or even permanent sick leave due to these problems. Most women in our study reported to have sufficient recovery opportunities, but over 90% of the participants reduced their weekly working hours after pregnancy. The question could be raised whether working hours were reduced to have enough recovery opportunities, especially to match private life demands, in order to achieve balance in work and family tasks. Eek et al., [32] found that women still take the largest responsibility for household and childcare leading to more stress and fatigue, thereby reducing their own health and well-being. Women have fewer recovery opportunities compared to men, leading to an increased risk of future sickness absence [33].

Nineteen women scored high on the need for recovery with a lack of recovery opportunities, indicating an imbalance in work load and recuperation time. We showed that especially younger women, who experienced preeclampsia/HELLP in their first pregnancy, were at risk of developing work-related fatigue. These women experienced work-family conflicts to a greater extent, which could be expected having a young child in need of care. However, it could also indicate that these women require an extended period to recover after the complicated pregnancy. As recovery seems to get better over time, screening on the need for recovery and recovery opportunities in women at return to work and in the first years afterwards might contribute to timely recognition of psychosocial problems. Early recognition of these issues after preeclampsia/HELLP is correlated with a shorter duration of treatment of these complaints [12].

In line with the assumption that women reduced their weekly working hours to meet private life demands, we showed that the main reason to reduce working hours was to combine work and private life. Unintended reduction was mainly driven by persistent complaints in combination with work-family conflict. These women scored higher on psychosocial aspects, need for recovery and recovery opportunities. Therefore, unintentional reduction of working hours after pregnancy might be a reason to initiate further investigations into work-related psychosocial aspects. The strength of this study is the use of validated questionnaires to evaluate work-related psychosocial aspects, need for recovery and recovery opportunities. This is the first study to evaluate these work-related psychosocial aspects in women with a history of preeclampsia/HELLP. However, several limitations of this study should be taken into account, such as the potential for selection due to the call for participation among members of the HELLP foundation. This may have led to inclusion of women with more severe complications during and/or after pregnancy. Furthermore, we used self-reported information on medical and obstetric history, including the type of hypertensive disorder of pregnancy, which may have resulted in some misclassification of these factors. We can only compare the results in this cohort of women with prior preeclampsia/HELLP with results in the general population. Therefore, it is impossible to determine whether the differences found are the result of prior preeclampsia/HELLP, reduced psychosocial functioning after becoming a mother leading to a change in responsibilities, or a combination of both.

Twenty-five percent of the women did not fully complete the questionnaire, mainly due to unemployment. As the standard questionnaires used were focused on work aspects, they were extremely difficult to complete when unemployed. We do not know whether the unemployment is the result of the pregnancy complications. If so, our results may be attenuated, since women who did not reintegrate after pregnancy might experience more severe impairments. Therefore, the results of this study are applicable to women still working after pregnancy only.

Conclusion

Work-related psychosocial aspects are affected by previous preeclampsia/HELLP, especially work pace, quantitative demands, and influence at work, leading to stress-related problems and reduction in working hours. Preeclampsia may negatively affect occupational activity and need for recovery. Early recognition of women with an elevated need for recovery, a lack of recovery opportunities, and unintended reduction of weekly working hours is necessary to prevent work-related stress. Prospective follow-up of work-related aspects both in women after a normotensive pregnancy and in women with a history of preeclampsia/HELLP is warranted to evaluate the long-term impact of preeclampsia.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the Dutch ‘HELLP Stichting’ for support in conducting this study and all participating women for their contribution.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection and analysis were performed by HM, NR and MFD. The first draft of the manuscript was written by HM and AM, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

A waiver was provided by the Regional Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects Arnhem-Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Availability of Data

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author, HM. The data are not publicly available due to the sensitive nature of the questions asked in this study.

References

- Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S, Magee LA, de Groot CJM, et al. (2016) Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 387: 999-1011.

- Dusse LM, Alpoim PN, Silva JT, Rios DR, Brandão AH, et al. (2015) Revisiting HELLP syndrome. Clin Chim Acta 451: 117-120.

- Sibai BM, Ramadan MK, Usta I, Salama M, Mercer BM, et al. (1993) Maternal morbidity and mortality in 442 pregnancies with hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelets (hellp syndrome). Am J Obstet Gynecol 169: 1000-1006.

- Leon LJ, McCarthy FP, Direk K, Gonzalez-Izquierdo A, Prieto-Merino D, et al. (2019) Preeclampsia and Cardiovascular Disease in a Large UK Pregnancy Cohort of Linked Electronic Health Records: A CALIBER Study. Circulation 140: 1050-1060.

- Basit S, Wohlfahrt J, Boyd HA (2018) Pre-eclampsia and risk of dementia later in life: nationwide cohort study. BMJ 363: 4109.

- Postma IR, Groen H, Easterling TR, Tsigas EZ, Wilson ML, et al. (2013) The brain study: Cognition, quality of life and social functioning following preeclampsia; an observational study. Pregnancy Hypertens 3: 227-234.

- Brussé I, Duvekot J, Jongerling J, Steegers E, De Koning I (2008) Impaired maternal cognitive functioning after pregnancies complicated by severe pre-eclampsia: A pilot case-control study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 87: 408-412.

- Elharram M, Dayan N, Kaur A, Landry T, Pilote L (2018) Long-term cognitive impairment after preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 132: 355-364.

- Postma IR, Bouma A, Ankersmit IF, Zeeman GG (2014) Neurocognitive functioning following preeclampsia and eclampsia: A long-term follow-up study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 211: 37.

- Mommersteeg PM, Drost JT, Ottervanger JP, Maas AH (2016) Long-term follow-up of psychosocial distress after early onset preeclampsia: The preeclampsia risk evaluation in females cohort study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 37: 101-109.

- Rep A, Ganzevoort W, Bonsel GJ, Wolf H, de Vries JI (2007) Psychosocial impact of early-onset hypertensive disorders and related complications in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 197: 158.

- Poel YH, Swinkels P, de Vries JI (2009) Psychological treatment of women with psychological complaints after pre-eclampsia. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 30: 65-72.

- Gaugler-Senden IP, Duivenvoorden HJ, Filius A, De Groot CJ, Steegers EA, et al. (2012) Maternal psychosocial outcome after early onset preeclampsia and preterm birth. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 25: 272-276.

- van Veldhoven M, Broersen S (2003) Measurement quality and validity of the "need for recovery scale". Occup Environ Med 60.

- van Veldhoven MJP, Sluiter JK (2009) Work-related recovery opportunities: Testing scale properties and validity in relation to health. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 82: 1065-1075.

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, et al. (2007) The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med 4: 296.

- Pejtersen JH, Kristensen TS, Borg V, Bjorner JB (2010) The second version of the copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Scand J Public Health 38: 8-24.

- Broersen JPJ, Fortuin RJ, Dijkstra L, van Veldhoven M, Prins J (2004) Monitor arboconvenanten: Kengetallen en grenswaarden. TBV - Tijdschrift voor Bedrijfs- en Verzekeringsgeneeskunde 12: 104-108.

- de Croon EM, Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH (2006) Psychometric properties of the need for recovery after work scale: Test-retest reliability and sensitivity to detect change. Occup Environ Med 63: 202-206.

- Nuebling M, Seidler A, Garthus-Niegel S, Latza U, Wagner M, et al. (2013) The gutenberg health study: Measuring psychosocial factors at work and predicting health and work-related outcomes with the eri and the copsoq questionnaire. BMC public health 13: 538.

- Burr H, Albertsen K, Rugulies R, Hannerz H (2010) Do dimensions from the copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire predict vitality and mental health over and above the job strain and effort-reward imbalance models? Scand J Public Health 38: 59-68.

- Fields JA, Garovic VD, Mielke MM, Kantarci K, Jayachandran M, et al. (2017) Preeclampsia and cognitive impairment later in life. Am J Obstet Gynecol 217: 74.

- Debette S, Markus HS (2010) The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 341: 3666.

- Soma-Pillay P, Suleman FE, Makin JD, Pattinson RC (2017) Cerebral white matter lesions after pre-eclampsia. Pregnancy Hypertens 8: 15-20.

- Aukes AM, De Groot JC, Wiegman MJ, Aarnoudse JG, Sanwikarja GS, et al. (2012) Long-term cerebral imaging after pre-eclampsia. BJOG 119: 1117-1122.

- Mielke MM, Milic NM, Weissgerber TL, White WM, Kantarci K, et al. (2016) Impaired cognition and brain atrophy decades after hypertensive pregnancy disorders. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 9: 70-76.

- Postma IR, Bouma A, de Groot JC, Aukes AM, Aarnoudse JG, et al. (2016) Cerebral white matter lesions, subjective cognitive failures, and objective neurocognitive functioning: A follow-up study in women after hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 38: 585-598.

- Honigberg MC, Zekavat SM, Aragam K, Klarin D, Bhatt DL, et al. (2019) Long-term cardiovascular risk in women with hypertension during pregnancy. J Am Coll Cardiol 74: 2743-2754.

- Di Pilla M, Bruno RM, Taddei S, Virdis A (2016) Gender differences in the relationships between psychosocial factors and hypertension. Maturitas 93: 58-64.

- van Amelsvoort LG, Kant IJ, Bültmann U, Swaen GM (2003) Need for recovery after work and the subsequent risk of cardiovascular disease in a working population. Occup Environ Med 60: 83-87.

- Sluiter JK, Frings-Dresen MH, van der Beek AJ, Meijman TF (2001) The relation between work-induced neuroendocrine reactivity and recovery, subjective need for recovery, and health status. J J Psychosom Res 50: 29-37.

- Eek F, Axmon A (2015) Gender inequality at home is associated with poorer health for women. Scand J Public Health 43: 176-182.

- Boschman JS, Noor A, Sluiter JK, Hagberg M (2017) The mediating role of recovery opportunities on future sickness absence from a gender- and age-sensitive perspective. PLoS One 12: 0179657.

Citation: Muijsers HEC, Maas AHEM, van der Heijden OWH, Roeleveld N, Frings-Dresen MHW (2021) The Impact of Preeclampsia on Work-Related Psychosocial Aspects and Need for Recovery. J Reprod Med Gynecol Obstet 6: 080.

Copyright: © 2021 Muijsers HEC, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.