Abstract

Several lines of evidence suggest that cytomegalovirus (CMV) may play an aetiological role in schizophrenia. Epidemiologically, both have a worldwide distribution and an increased prevalence in lower socioeconomic groups. Studies have reported that some patients experiencing initial episodes of schizophrenia have increased levels of IgG antibodies against CMV, but not other herpes viruses, in their sera and CSF. Treatment with antipsychotic medications may result in a decrease in CMV antibodies, while treatment with anti-herpes virus and anti-inflammatory medications may reduce symptoms in some individuals with schizophrenia. There is also some overlap in the genes that are thought to operate in CMV infections and schizophrenia.

The strongest argument against the role of CMV in schizophrenia is the absence of the traditional CMV neuropathological changes in the brains of individuals with schizophrenia; however, neuropathological studies of CMV have mostly been conducted in immune-compromised individuals.

Further studies on CMV and schizophrenia are needed and may lead to improved treatments for schizophrenia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Schizophrenia is a chronic neuropsychiatric disease characterised by abnormalities in brain structure and function.[1] It has been established that both genetic and environmental factors play a role in the aetiology of schizophrenia; the latter include an excess of winter-spring births,[2] an excess of urban births[3] and an excess of births in lower socioeconomic groups.[4]

Speculation regarding a possible infectious cause of schizophrenia was prominent in the early 20th century. The 1918 influenza pandemic was followed by multiple reports of cases of post-influenza psychoses with schizophrenia-like symptoms, and by 1928 it was said that “encephalitis and schizophrenia are different diseases, but it seems that some common factor to both is sometimes present and accounts for the coincidence of identical symptoms”.[5] In 1932, researchers reported having injected CSF from patients with schizophrenia into the brains of rabbits, and a recommendation was made to extend the experiments to ‘cats, dogs and apes’ by inoculating them with “vaccinia variola, measles, rubella… and herpes virus, with a view to producing encephalitis… and comparison with such a condition as katatonic stupor”.[6]

Research on a possible infectious cause of schizophrenia then fell out of favour until the last few decades of the century. In recent years, there have been reports suggesting that Toxoplasma gondii,[7,8] retroviruses,[9,10] herpes simplex virus (HSV) type 1,[11] HSV-2,[12] and cytomegalovirus (CMV)[13] may be aetiologically important in schizophrenia. This paper will review evidence regarding a possible link between CMV and schizophrenia.

1. Clinical Aspects

CMV is a β-herpes virus found only in humans and spread by direct contact (saliva, blood, semen, vaginal secretions, breast milk). Infection rates increase with age and are higher in lower socioeconomic groups.[14] The primary infection is usually asymptomatic, after which the virus latently infects the person for the remainder of their lifetime and is kept in check by the immune response, which particularly involves cytokines.[15,16] Any impairment of the immune response may lead to activation of the infectious process, such as is seen in individuals undergoing immune-suppressive chemotherapy or those affected by an HIV infection. When primary infection occurs in pregnant women, the virus may cross the placenta and cause a congenital infection characterised by hearing loss, visual impairment, mental retardation and microencephaly.[15,16]

CMV is neurotrophic and has an affinity for the limbic system,[17] one of the areas of the brain thought to be affected in schizophrenia.[18] CMV encephalitis presents in adults as a variety of neurological symptoms, with most cases occurring in HIV-infected and immune-suppressed patients.[19] One reported case was that of a non-immune-suppressed patient who presented with auditory hallucinations, delusions, tangential thinking and flattened affect, and was initially diagnosed with schizophrenia, until a presumptive diagnosis of CMV encephalitis was made postmortem based on neuropathological findings and retrospective antibody levels in the CSF.[20] It is also of interest to note that CMV infections in rodent models are associated with a deficit in sensorimotor gating that is similar to that widely reported in individuals with schizophrenia.[21]

A study of 323 patients with schizophrenia, divided into groups according to whether they primarily had deficit (n = 88) or nondeficit (n = 235) symptoms, reported that IgG antibodies against CMV, but not to other herpes viruses, were significantly more common in patients with the deficit syndrome (p = 0.006).[22]

2. Serological Studies

Between 1973 and 1992, 14 studies were reported on serum CMV antibody levels in patients with chronic schizophrenia; all reported no significant difference in levels between patients and controls (see review by Yolken and Torrey[23]). However, these studies were limited by the use of complement fixation or other less sensitive assays, by using problematic control groups, and, in particular, by studying patients who had been unwell for many years.

In recent years, five additional serological studies have been carried out in patients with a more recent onset of illness. In India, Srikanth et al.[24] reported elevated CMV antibody levels in 6 of 35 individuals with an onset of psychosis within the previous month compared with 35 controls undergoing minor surgical procedures. In Germany, a comparison was made between 86 patients with schizophrenia (mean age 30.7 ± 9.4 years), 29 of whom were experiencing their first episode, and 85 unaffected control individuals (mean age 27.8 ± 7.4 years) recruited from the general population (Schwarz MJ and Mueller N, unpublished observations). Significantly more patients than control individuals had antibodies to CMV (Chi-square 10.29; p = 0.001) but not to other herpes viruses. Also in Germany, a comparison was made between 34 patients with a first episode of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or psychosis not otherwise specified (mean age 28.4 ± 8.9 years) and 27 unaffected matched controls (Bachmann S et al., unpublished observations). A significantly higher proportion of patients had antibodies against CMV (Chi-square test; p < 0.005), and the reactivity of the patients’ sera, as measured by enzyme immunoassay in optical density, was significantly stronger than that of control individuals (Mann-Whitney U-test; p < 0.001). In both of these unpublished studies, the control groups were well matched with the patients with psychotic disorders in terms of socioeconomic and geographical variables, making it unlikely that the differences were related to differential exposure to CMV as a result of these factors.

In Baltimore, USA, a comparison was made between 415 outpatients with schizophrenia and 164 unaffected matched controls recruited from the community (Dickerson F et al., unpublished observations). The patients with schizophrenia were significantly more likely to be seropositive for CMV than the control individuals (42% vs 23%; odds ratio 2.1 [95% CI 1.2, 3.5]; p = 0.009). Compared with those patients who were seronegative for CMV, seropositive patients were more likely to be female, African-American, older and less educated.

The final recent serological study was carried out in Germany by Leweke et al.[25] and will be discussed in section 3.

3. CSF Studies

In the US in 1980, Albrecht et al.[26] reported that 60 patients with chronic schizophrenia had a significantly increased CSF/serum CMV antibody ratio compared with 26 control individuals (p = 0.001). In 1982, in a study performed in the US, Torrey et al.[13] reported that 20 of 178 (11%) patients with schizophrenia had CMV IgM (but not IgG or IgA) antibodies compared with none of 41 controls (p = 0.025). Two of the CMV-positive patients were experiencing their first episode of schizophrenia and had not been previously treated with antipsychotic medications. A second CSF specimen was available within 2 months of the original specimen for 2 of the 20 CMV IgM antibody-positive patients; this second specimen was also positive in both patients. In a third patient, a second specimen was obtained 1 year later, which was found to be negative.

Since 1980, eight other studies have assessed CMV antibodies in the CSF of individuals with schizophrenia.

In Israel, Gotlieb-Stematsky et al.,[27] and in Finland, Rimón et al.,[28] examined 19 and 40 individuals with schizophrenia, respectively, and used individuals undergoing lumbar punctures for neurological reasons as controls; no individual in any group had antibodies to CMV that were detectable using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. In England, Shrikhande et al.[29] assessed 32 individuals with schizophrenia and ten control patients with orthopaedic problems; only one patient with schizophrenia and four of the patients with orthopaedic problems had CMV antibodies in their CSF.

In Northern Ireland, King et al.[30] assessed 20 patients with chronic schizophrenia and 36 orthopaedic patients; the former group had a nonsignificant increase in the CSF levels of antibodies against CMV. In a study that was also performed in Ireland, CMV IgM antibodies were found in the CSF of 9 of 34 inpatients with schizophrenia compared with 1 of 20 hospital personnel controls (Torrey EF and Yolken RH, unpublished observations).

In US studies, Kaufmann et al.[31] reported the presence of CMV IgM antibodies in the CSF of 7 of 35 patients with schizophrenia and one of six control individuals with neurological conditions, while Van Kammen et al.[32] reported similar findings in 5 of 27 patients with schizophrenia who had been medication-free for an average of 32 days; unfortunately, a control group was not included in the latter study.

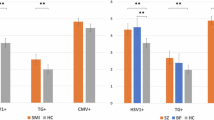

The most recent CSF study was carried out by Leweke et al.[25] in Germany. CMV IgG and IgM antibody levels were compared for both the serum and CSF of 36 first-episode, never-treated individuals with schizophrenia, ten individuals with schizophrenia who were currently medication-free but had been treated in the past, 39 individuals with recent-onset schizophrenia who were receiving medication and 73 unaffected control volunteers. For both the serum and CSF, CMV IgG antibody levels were significantly higher (serum p < 0.001; CSF p < 0.004) in the individuals with schizophrenia that had never been treated compared with the unaffected controls. Particularly noteworthy was the gradual decrease in antibody levels in both the serum and CSF from patients who were never treated to those who had previously been treated, to those currently receiving treatment, suggesting that the medication decreased the antibody response to CMV (see figure 1). There were no significant differences in levels of IgM antibodies against CMV between groups (data not shown), suggesting that the CMV infection was not of recent onset. CMV DNA was also amplified from the CSF of one of the patients with schizophrenia, using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR); sequence analysis showed that it was similar to common strains of the virus. The rate of amplification of CMV DNA from the CSF was not different from that expected from a control population of patients seropositive for CMV.

Levels of IgG antibodies to cytomegalovirus in the (a) serum and (b) CSF of individuals with recent-onset schizophrenia who had never been treated with antipsychotic medication (Never therapy); had received medication in the past (Past therapy); who were receiving medication at the time of the study (Current therapy); or who were controls without psychiatric disease (Controls). Bars represent the mean and 95% confidence intervals of the antibody levels expressed in standardised units (reproduced from Leweke et al.,[25] with kind permission from Springer Science and Business Media). ⋆ p < 0.04, ⋆⋆ p < 0.004, ⋆⋆⋆ p < 0.001 vs controls.

4. Brain Studies

Nine studies have attempted to identify the CMV genome, using hybridisation or PCR techniques, in postmortem brain tissue from individuals with schizophrenia (see review by Yolken and Torrey[23]). In one study, “a clear hybridisation signal was detected with DNA from the temporal cortex of a young man with the full picture of schizophrenia”,[33] but the other eight studies reported negative findings (Yolken and Torrey[23] and Conejero-Goldberg et al.[34]).

5. Effects of Treatment with Anti-Cytomegalovirus Medications in Patients with Schizophrenia

The study by Leweke et al.[25] suggests that antipsychotic medication may suppress CMV antibody formation. This raises the question of whether other drugs known to suppress CMV can improve symptoms in individuals with schizophrenia. Two such recent studies have been carried out.[35,36]

In one study,[35] 65 outpatients with schizophrenia receiving current treatment with antipsychotics were treated for 16 weeks with adjunctive valaciclovir, which is known to suppress the DNA replication of several members of the herpes virus family, including HSV-1, HSV-2, CMV and the varicella zoster virus (VZV). Antibody status with regards to several viruses was assessed in the study individuals. Twenty-one of the 65 patients included in the study were CMV seropositive. It was found that “individuals who were seropositive for CMV displayed a significant improvement in overall symptoms” (p < 0.0005); no such improvement was seen for individuals who were seropositive for HSV-1, HSV-2, Epstein-Barr virus, VZV or human herpesvirus 6. This suggests that the replication of CMV may be playing a role in causing the symptoms of schizophrenia in some individuals.

In the other study,[36] celecoxib, a selective inhibitor of cyclo-oxygenase (COX)-2, was administered in conjunction with risperidone in a double-blind trial of 50 patients with an acute exacerbation of their schizophrenia. Those receiving the adjunctive celecoxib had a significant improvement in their symptoms, which was greatest between weeks 2 and 4 (p = 0.001). Since it is known that CMV infection increases COX-2 expression[37] and that inhibition of COX-2 blocks the replication of CMV,[38] this mechanism may account for the improvement shown by patients in this study.

6. Genetic Studies

Predisposing genes are also known to be important in both CMV infection and schizophrenia. In this regard, resistance to CMV infection in humans is associated with variations in the gene encoding tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α.[39] Variations in the promoter and coding regions of this gene have also been found to be associated with an increased risk of schizophrenia in some studies,[40,41] but not others.[42] Similarly, variations in the gene encoding the cytokine interleukin 10 have been associated with susceptibility to both CMV infections and schizophrenia.[43,44] CMV strain differences, which have been well described, may account for different outcomes from the infectious process.

A recent study[45] looked specifically for a genetic linkage between CMV and schizophrenia. A comparison of the presence of CMV antibodies in families with multiple members affected by schizophrenia (multiplex) versus one affected member (simplex) found the presence of CMV antibodies in more family members in the former group. Additional examination of 46 single nuclear polymorphisms (SNPs) on 11 genes on chromosome 6p21-23, a region with many immune-related genes, showed ‘significant linkage and association’ between schizophrenia and CMV and SNPs for two genes – TNF and major histocompatibility complex class I chain-related gene B (MICB). The authors concluded that the results “suggest an intriguing interaction between exposure to CMV and variation at MICB and TNF or other linked loci in the aetiology of schizophrenia”.[45]

7. Neuropathological Aspects

The strongest argument against CMV playing a primary aetiological role in schizophrenia is the absence of characteristic CMV neuropathological changes in the brains of patients with schizophrenia. CMV-induced changes of the adult brain have been studied most extensively in individuals who were immune-compromised due to having AIDS or receiving immunosuppressive therapy following an organ transplant. In such individuals, CMV-encephalitis, histopathologically characterised by scattered gliomesenchymal nodules and a necrotising encephalopathy, with typical Cowdry type A inclusion bodies commonly seen in a periventricular localisation, is a common finding;[46] however, inclusion bodies are often absent in CMV infections of the brain and thus cannot be used as definitive diagnostic criteria.[47,48] Very few neuropathological studies have been carried out on immune-competent adults; those that have been conducted showed encephalitis and polyneuritis, but such findings are said to be ‘an uncommon event’.[46] Animal studies suggest that the brains of immune-competent rats are relatively resistant to CMV infections.[49]

8. Conclusions

Despite contradictory data, several studies suggest some relationship between CMV infection and schizophrenia. There appear to be some common genetic links, and an increase in CMV antibodies is seen in some populations of patients with first-episode, never-treated schizophrenia. However, it should be noted that much of the positive data is unpublished and therefore should be regarded as preliminary. The relationship may be aetiological or may be due to increased exposure to CMV in individuals who develop the symptoms of schizophrenia. Failure to find, to date, CMV or neuropathological evidence of CMV in the brains of patients with schizophrenia argues against an aetiological relationship. Nevertheless, the finding that anti-CMV medications improve the symptoms of some individuals with schizophrenia provides therapeutic possibilities that deserve further exploration.

References

Torrey EF. Studies of individuals with schizophrenia never treated with antipsychotic medications: a review. Schizophr Res 2002 Dec; 58(2–3): 101–15

Torrey EF, Miller J, Rawlings R, et al. Seasonality of births in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review of the literature. Schizophr Res 1997 Nov; 28(1): 1–38

Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB, Westergaard T, et al. Effects of family history and place and season of birth on the risk of schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 1999 Feb; 340(8): 603–8

Harrison G, Gunnell D, Glazebrook C, et al. Association between schizophrenia and social inequality at birth: case-control study. Br J Psychiatry 2001 Oct; 179: 346–50

Hendrick I. Encephalitis lethargica and the interpretation of mental disease. Am J Psychiatry 1928; 7: 989–1014

Goodall E. The exciting cause of certain states of disease, at present classified under “schizophrenia” by psychiatrists, may be infection. J Ment Sci 1932; 78: 746–55

Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia. Emerg Infect Dis 2003 Nov; 9(11): 1375–80

Yolken RH, Bachmann S, Rouslanova I, et al. Antibodies to Toxoplasma gondii in individuals with first-episode schizophrenia. Clin Infect Dis 2001 Mar; 32(5): 842–4

Karlsson H, Bachmann S, Schröder J, et al. Retroviral RNA identified in the cerebrospinal fluids and brains of individuals with schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2001 Apr; 98(8): 4634–9

Hart DJ, Heath RG, Sautter Jr FJ, et al, editor. Antiretroviral antibodies: implications for schizophrenia, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and bipolar disorder. Biol Psychiatry 1999 Mar; 45(6): 704–14

Dickerson FB, Boronow JJ, Stallings C, et al. Association of serum antibodies to herpes simplex virus 1 with cognitive deficits in individuals with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003 May; 60(5): 466–72

Buka SL, Tsuang MT, Torrey EF, et al. Maternal infections and subsequent psychosis among offspring. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2001 Nov; 58(11): 1032–7

Torrey EF, Yolken RH, Winfrey CJ. Cytomegalovirus antibody in cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients detected by enzyme immunoassay. Science 1982 May; 216(4548): 892–3

Dauncey K, Giggs J, Baker K, et al. Schizophrenia in Nottingham: lifelong residential mobility of a cohort. Br J Psychiatr 1993; 163: 613–9

Griffiths PD, McLaughlin JE. Cytomegalovirus. In: Scheid WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, editors. Infections of the central nervous system. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2004: 159–173

Scheid WM, Whitley RJ, Marra CM, editors. Infections of the central nervous system. 3rd ed. New York: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2004

Hanshaw JB. Cytomegalovirus. In: Remington JS, Klein JO, editors. Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant. Philadelphia (PA): Saunders, 1976: 127

Torrey EF, Peterson MR. Schizophrenia and the limbic system. Lancet 1974 Oct; II(7886): 942–6

Arribas JR, Storch GA, Clifford DB, et al. Cytomegalovirus encephalitis. Ann Intern Med 1996 Oct; 125(7): 577–87

Torrey EF. Functional psychoses and viral encephalitis. Integr Psychiatry 1986; 4: 224–36

Rothschild DM, O’Grady M, Wecker L. Neonatal cytomegalovirus exposure decreases prepulse inhibition in adult rats: implications for schizophrenia. J Neurosci Res 1999 Aug; 57(4): 429–34

Dickerson F, Kirkpatrick B, Boronow J, et al. Deficit schizophrenia: association with serum antibodies to cytomegalovirus. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32(2): 396–400

Yolken RH, Torrey EF. Viruses, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Clin Microbiol Rev 1995 Jan; 8(1): 131–45

Srikanth S, Ravi V, Poornima KS, et al. Viral antibodies in recent onset, nonorganic psychoses: correspondence with symptomatic severity. Biol Psychiatry 1994 Oct; 36(8): 517–21

Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Koethe D, et al. Antibodies to infectious agents in individuals with recent onset schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2004 Feb; 254(1): 4–8

Albrecht P, Torrey EF, Boone E, et al. Raised cytomegalovirus-antibody level in cerebrospinal fluid of schizophrenic patients. Lancet 1980 Oct; II(8198): 769–72

Gotlieb-Stematsky T, Zonis J, Arlazoroff A, et al. Antibodies to Epstein-Barr virus, herpes simplex type 1, cytomegalovirus and measles virus in psychiatric patients. Arch Virol 1981; 67(4): 333–9

Rimón R, Ahokas A, Palo J. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid antibodies to cytomegalovirus in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1986 Jun; 73(6): 642–4

Shrikhande S, Hirsch SR, Coleman JC, et al. Cytomegalovirus and schizophrenia: a test of a viral hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry 1985 May; 146: 503–6

King DJ, Cooper SJ, Earle JAP, et al. Serum and CSF antibody titres to seven common viruses in schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 1985 Aug; 147: 145–9

Kaufmann CA, Weinberger DR, Yolken RH, et al. Viruses and schizophrenia. Lancet 1983 (Nov); II(8359): 1136–7

van Kammen DP, Mann L, Scheinin M, et al. Spinal fluid monoamine metabolites and anti-cytomegalovirus antibodies and brain scan evaluation in schizophrenia. Psychopharm Bull 1984 Summer; 20(3): 519–22

Moises HW, Rüger R, Reynolds GP, et al. Human cytomegalovirus DNA in the temporal cortex of a schizophrenic patient. Eur Arch Psychiatry Neurol Sci 1988; 238(2): 110–3

C, Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Herpesviruses and Toxoplasma gondii in orbital frontal cortex of psychiatric patients. Schizophr Res 2003 Mar; 60(1): 65–9

Dickerson FB, Boronow JJ, Stallings CR, et al. Reduction of symptoms by valacyclovir in cytomegalovirus-seropositive individuals with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2003 Dec; 160(12): 2234–6

Mueller N, Riedel M, Scheppach C, et al. Beneficial antipsychotic effects of celecoxib add-on therapy compared to risperidone alone in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2002 Jun; 159(6): 1029–34

Martelius TJ, Wolff H, Bruggeman CA, et al. Induction of cyclo-oxygenase-2 by acute liver allograft rejection and cytomegalovirus infection in the rat. Transpl Int 2002 Dec; 15(12): 610–4

Zhu H, Cong JP, Yu D, et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase 2 blocks human cytomegalovirus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002 Mar; 99(6): 3932–7

Hurme M, Helminen M. Resistance to human cytomegalovirus infection may be influenced by genetic polymorphisms of the tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist genes. Scand J Infect Dis 1998; 30(5): 447–9

Schwab SG, Mondabon S, Knapp M, et al. Association of tumor necrosis factor alpha gene-G308A polymorphism with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003 Dec; 65(1): 19–25

Boin F, Zanardini R, Pioli R, et al. Association between -G308A tumor necrosis factor alpha gene polymorphism and schizophrenia. Mol Psychiatry 2001 Jan; 6(1): 79–82

Riedel M, Krönig H, Schwarz MJ. No association between the G308A polymorphism of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene and schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2002 Oct; 252: 232–4

Hurme M, Haanpaa M, Nurmikko T, et al. IL-10 gene polymorphism and herpesvirus infections. J Med Virol 2003; 70Suppl. 1: S48–50

Chiavetto LB, Boin F, Zanardini R, et al. Association between promoter polymorphic haplotypes of interleukin-10 gene and schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2002 Mar; 51(6): 480–4

Kim JJ, Dayal M, Bacanu S, et al. Exposure to cytomegalovirus and polymorphisms in two genes on chromosome 6p21-23 as joint risk factors for schizophrenia [abstract]. Am J Med Genetics B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004 Sept; 130B(1): 19

Craighead JE. Cytomegalovirus. In: Pathology and pathogenesis of human viral disease. San Diego (CA): Academic Press, 2000: 87–115

Bailey OT, Wolf A, Schneck SA, et al. Iatrogenic modification of tissue responses to infectious agents in the central nervous system. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis 1968; 44: 445–62

Dorfman LJ. Cytomegalovirus encephalitis in adults. Neurology 1973 Feb; 23(2): 136–44

Reuter JD, Gomez DL, Wilson JH, et al. Systemic immune deficiency necessary for cytomegalovirus invasion of the mature brain. J Virol 2004 Feb; 78(3): 1473–87

Acknowledgements

Financial support for this study was provided by the Stanley Medical Research Institute. None of the authors have any conflicts of interest that are relevant to the contents of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Torrey, E.F., Leweke, M.F., Schwarz, M.J. et al. Cytomegalovirus and Schizophrenia. CNS Drugs 20, 879–885 (2006). https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200620110-00001

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00023210-200620110-00001