Abstract

Objective

To determine the agreement between two measures of medication use, namely telephone interview self-report and pharmaceutical claims data, in an elderly population.

Methods

An agreement study of 566 community-dwelling, general practice patients aged ≥65 years was conducted to compare self-reported use of medicines with pharmaceutical claims data for different retrieval periods. Classes of drugs commonly used in the elderly were selected for comparison.

Results

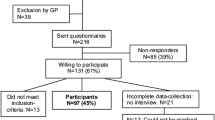

1094 people were eligible for the main study. Of these, 697 people completed a follow-up survey and 625 of these patients consented to the release of pharmaceutical claims data. A further 59 participants were excluded from the analysis because they had a home visit instead of a telephone interview. The proportion of observed agreement between the telephone self-report and the various retrieval periods was consistently high. Kappa coefficients showed good to very good agreement (≥0.75) with retrieval periods of 30, 60 and 90 days for benzodiazepines, low-risk NSAIDs, thiazide diuretics and most other drugs. The specificity of self-reported medication use compared with claims data was consistently high across all drug classes, suggesting that people usually did not mention drugs that were not included in the claims data. Sensitivity values varied according to drug class and retrieval period, and were lower for NSAIDs than for benzodiazepines and thiazide diuretics. Decline in sensitivity with increased retrieval periods was most marked for benzodiazepines, NSAIDs and low-risk NSAIDs, which are often used on an as-needed basis. Positive predictive values increased with longer retrieval periods

Conclusion

High agreement and accuracy were demonstrated for self-reported use of medicines when patients were interviewed over the telephone compared with pharmaceutical claims data. The telephone inventory method can be used in future studies for accurately measuring drug use in older people when claims data are not available.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey 1995: use of medications. Canberra (ACT): Australian Bureau of Statistics, 1999

Hancock L, Walsh R, Henry DA, et al. Drug use in Australia: a community prevalence study. Med J Aust 1992; 156: 759–64

Metlay JP, Hardy C, Strom BL. Agreement between patient self-report and a Veterans’ Affairs national pharmacy database for identifying recent exposures to antibiotics. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2003; 12(1): 9–15

Bonevski B, Sanson-Fisher RW, Campbell EM, et al. Do general practice patients find computer health risk surveys acceptable? A comparison with pen and paper method. Health Promot J Austr 1997; 7(2): 100–6

Silman A. Epidemiological studies: a practical guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995

Bonevski BA. Increasing preventive care in general practice: an examination [doctoral dissertation]. Newcastle (NSW): University of Newcastle, 1996

Farmer KC. Methods for measuring and monitoring medication regimen adherence in clinical trials and clinical practice. Clin Ther 1999; 21(6): 1074–90; discussion 3

Cockburn J. Variables related to antibiotic compliance in general practice patients: the application of behavioural science methodologies [doctoral dissertation]. Newcastle (NSW): University of Newcastle, 1986

Klungel OH, de Boer A, Paes AH, et al. Influence of question structure on the recall of self-reported drug use. J Clin Epidemiol 2000; 53(3): 273–7

Hancock L. Drug use in the Australian community: prevalence, sociodemographic characteristics of users, and context of use [doctoral dissertation]. Newcastle (NSW): University of Newcastle, 1991

Stewart M. The validity of an interview to assess a patient’s drug taking. Am J Prev Med 1987; 3(2): 95–100

Kehoe R, Wu SY, Leske MC, et al. Comparing self-reported and physician-reported medical history. Am J Epidemiol 1994; 139(8): 813–8

Paganini-Hill A, Ross RK. Reliability of recall of drug usage and other health-related information. Am J Epidemiol 1982; 116(1): 114–22

Lau HS, de Boer A, Beuning KS, et al. Validation of pharmacy records in drug exposure assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 1997; 50(5): 619–25

West SL, Savitz DA, Koch G, et al. Recall accuracy for prescription medications: self-report compared with database information. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 142(10): 1103–12

Klungel OH, de Boer A, Paes AH, et al. Agreement between self-reported antihypertensive drug use and pharmacy records in a population-based study in The Netherlands. Pharm World Sci 1999; 21(5): 217–20

Sjahid SI, van der Linden PD, Stricker BH. Agreement between the pharmacy medication history and patient interview for cardiovascular drugs: the Rotterdam elderly study. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1998; 45(6): 591–5

Wang PS, Benner JS, Glynn RJ, et al. How well do patients report noncompliance with antihypertensive medications? A comparison of self-report versus filled prescriptions. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2004; 13(1): 11–9

Johnson RE, Vollmer WM. Comparing sources of drug data about the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991; 39(11): 1079–84

Robertson J, Fryer JL, O’Connell DL, et al. Limitations of Health Insurance Commission (HIC) data for deriving prescribing indicators. Med J Aust 2002; 176(9): 419–24

King MA, Purdie DM, Roberts MS. Matching prescription claims with medication data for nursing home residents: implications for prescriber feedback, drug utilisation studies and selection of prescription claims database. J Clin Epidemiol 2001; 54(2): 202–9

Young AF, Dobson AJ, Byles JE. Health services research using linked records: who consents and what is the gain?. Aust N Z J Public Health 2001; 25(5): 417–20

Pit S, Byles J, Henry D, et al. A Quality Use of Medicines program for general practitioners and older people: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust 2007; 187(1): 23–30

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. Anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification index with defined daily doses (DDDs). Oslo: WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology, 2001

Byrt T, Bishop J, Carlin JB. Bias, prevalence and kappa. J Clin Epidemiol 1993; 46(5): 423–9

Robertson J, Fryer JL, O’Connell DL, et al. The impact of specialists on prescribing by general practitioners. Med J Aust 2001; 175(8): 407–11

Choo PW, Rand CS, Inui TS, et al. Validation of patient reports, automated pharmacy records, and pill counts with electronic monitoring of adherence to antihypertensive therapy. Med Care 1999 Sep; 37(9): 846–57

Smith NL, Psaty BM, Heckbert SR, et al. The reliability of medication inventory methods compared to serum levels of cardiovascular drugs in the elderly. J Clin Epidemiol 1999; 52(2): 143–6

Kable S. An application of interactive computer programs to promote adherence to clinical practice guidelines for childhood asthma in general practice [doctoral dissertation]. Newcastle (NSW): University of Newcastle, 2004

Reeve JF, Peterson GM, Rumble RH, et al. Programme to improve the use of drugs in older people and involve general practitioners in community education. J Clin Pharm Ther 1999; 24(4): 289–97

Department of Health and Ageing. Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme: Medicare cards and fairer benefits, 8 May 2002 [online]. Available from URL: http://www.health.gov.au/haf/ime/ [Accessed 2003 October 18]

Acknowledgements

The National and Health Medical Research Council, Australia funded the study but played no role in the formulation of the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis or preparation of this paper. SWP received a University of Newcastle Postgraduate Scholarship as a PhD student. The researchers are independent from the funding body. The researchers in the Faculty of Health are members of the Hunter Medical Research Institute.

We thank all the general practitioners (in particular Dr Parker Magin and Dr Peter Hopkins) and their patients for participating in this study; Vibeke Hansen for managing and assisting in data collection; Deborah Bowman for research assistance; Professor Tony Smith, Professor David Henry, Lucy Holt and participating general practitioners for providing extensive advice on development of the content of the medication review checklist; Chris Bonner for advice and providing the Therapeutic Flags manual; Professor Paul Glasziou for developing the grant; the peer reviewers of the thesis for their comments; the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners for approving parts of the research as a clinical audit and as a Continuing Professional Development activity; the National Prescribing Service for approving Practice Incentive Payments; Medicare Australia for providing data; all advisory group members (in particular Judith Mackson [National Prescribing Service] and Professor Kichu Nair) for their advice; all interviewers; and all statisticians involved in this study.

JC (deceased) conceived, designed, analysed and interpreted the results of the study. SWP and JEB designed, analysed and interpreted the results of the study. JC and JB developed the grant. SWP managed and conducted the study and drafted the manuscript. JEB conceived the study, and revised the manuscript. SWP and JEB contributed to the final version. SWP and JEB are guarantors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Professor Jill Cockburn passed away on 13 October 2004. She was an outstanding academic and teacher at the University of Newcastle with a national and international reputation in the field of health behaviour, including healthcare delivery, medical education, teaching interactional skills, quality assurance, quality use of medicines and cancer control.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pit, S.W., Byles, J.E. & Cockburn, J. Accuracy of Telephone Self-Report of Drug Use in Older People and Agreement with Pharmaceutical Claims Data. Drugs Aging 25, 71–80 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200825010-00008

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002512-200825010-00008