Abstract

Objective: Esomeprazole, the S-isomer of omeprazole, was launched in the UK in September 2000. The first proton pump inhibitor, omeprazole, has been marketed in the UK for over 10 years. However, the adverse event database of newly marketed drugs is limited, and it is only after widespread clinical use that the adverse effect profile of a drug is ascertained more comprehensively. This study aims to monitor the safety of esomeprazole prescribed in the primary care setting in England using prescription-event monitoring (PEM).

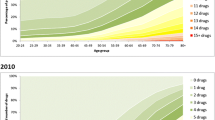

Methods: A postmarketing surveillance study using the observational cohort technique of PEM. Patients were identified from dispensed prescriptions for esomeprazole issued by general practitioners between September 2000 and April 2001. Questionnaires (‘green forms’) requesting clinical event data on these patients were sent to prescribers approximately 6 months after the date of the first dispensed prescription for each individual patient. Incidence densities (IDs), expressed as the number of first reports of an event/1000 patient-months of exposure (PME), were calculated. Significant differences between IDs for events reported in the first month (ID1) and the following 5 months (ID2–6) of exposure were regarded as potential signals. Other methods for signal detection such as medical evaluation of selected events and evaluation of reasons for stopping were also applied.

Results: Green forms containing clinically useful information for 11 595 patients (median age 56 years; 53.2% female) were received. Diarrhoea was the event with the highest ID1 in month 1 (8.0 per 1000 patient months of exposure). Adverse events that occurred significantly more often in the first month of treatment with esomeprazole compared with months 2–6 included diarrhoea, nausea/vomiting, abdominal pain, dyspepsia, headache/migraine, intolerance, malaise/lassitude, pruritis, unspecified adverse effects and abnormal sensation.

Conclusions: The safety profile of esomeprazole was consistent with the prescribing information and experience reported in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Rawlins MD, Jefferys DB. United Kingdom product licence applications involving new active substances, 1987–1989: their fate after appeals. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1993 Jun; 35(6): 599–602

Waller PC, Coulson RA, Wood SM. Regulatory pharmacovigilance in the United Kingdom: current principles and practice. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 1996 Nov; 5(6): 363–75

Thitiphuree S, Talley NJ. Esomeprazole, a new proton pump inhibitor: pharmacological characteristics and clinical efficacy. Int J Clin Pract 2000; 54(8): 537–41

Scott LJ, Dunn CJ, Mallarkey G, et al. Esomeprazole: a review of its use in the management of acid-related disorders. Drugs 2002; 62(10): 1503–38

Shakir SA. PEM in the UK. In: Mann RD, Andrews E, editors. Pharmacovigilance. 1st ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2002: 333–44

Shakir SAW. Causality and correlation in pharmacovigilance. In: Talbot J, Waller PC, editors. Stephens’ detection of new adverse drug reactions. 5th ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 2004: 329–43 323

Strom B. Sample size considerations for pharmacoepidemiology studies. In: Strom B, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 2nd ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd, 1994: 31–9

Machin D, Campbell M, Fayers P, et al. Post marketing surveillance: sample sizes required to observe a single adverse reaction with a given probability and anticipated incidence. In: Machin D, editor. Sample size tables for clinical studies. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd, 1997: 150

Machin D, Campbell M, Fayers P, et al. Post marketing surveillance: sample sizes for detection of a specified adverse reaction, background incidence known. In: Machin D, editor. Sample size tables for clinical studies. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science Ltd, 1997: 151–3

CIOMS/WHO. International guidelines for biomedical research involving human subjects. Geneva: CIOMS/WHO, 2002

Royal College of Physicians. Guidelines on the practice of ethical committees in medical research involving human subjects. 3rd ed. London: Royal College of Physicians of London, 1996

Department of Health. Supplementary operational guidelines for NHS Research Ethics Committees — November 2000: multi-centre research in the NHS the process of ethical review when there is no local researcher online]. Available at URL: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4006696 Accessed 2008 Mar 14]

Castell DO, Kahrilas PJ, Richter JE, et al. Esomeprazole (40 mg) compared with lansoprazole (30 mg) in the treatment of erosive esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97(3): 575–83

Maton PN, Vakil NB, Levine JG, et al. Safety and efficacy of long term esomeprazole therapy in patients with healed erosive oesophagitis. Drug Saf 2001; 24(8): 625–35

Shakir SAW. Prescription-event monitoring. In: Strom B, editor. Pharmacoepidemiology. 4th ed. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2005: 203–16

Martin RM, Dunn NR, Freemantle S, et al. The rates of common adverse events reported during treatment with proton pump inhibitors used in general practice in England: cohort studies. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2000 Oct; 50(4): 366–72

Wilton LV, Key C, Shakir SA. The pharmacovigilance of pantoprazole: the results of postmarketing surveillance on 11541 patients in England. Drug Saf 2003; 26(2): 121–32

AstraZeneca. Nexium (Esomeprazole) summary of product characteristics]. 2000 Jul

AstraZeneca. Nexium (Esomeprazole) summary of product characteristics]. 2003 Jan

Schöuhöfer PS, Werner B, Troger U. Ocular damage associated with proton pump inhibitors. BMJ 1997 Jun 21; 314(7097): 1805

Riordan-Eva P, Sanders MD. Omepraxole and ocular damage: facts of cases are unclear. BMJ 1998 Jan 3; 316(7124): 67

Lessell S. Omepraxole and ocular damage: concerns on safety of drug are unwarranted. BMJ 1998 Jan 3; 316(7124): 67

Garcia Rodriguez LA, Mannino S, Wallander MA, et al. A cohort study of the ocular safety of anti-ulcer drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 1996 Aug; 42(2): 213–6

Lalkin A, Loebstein R, Addis A, et al. The safety of omeprazole during pregnancy: a multicenter prospective controlled study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998 Sep; 179 (3 Pt 1): 727–30

Kallen BA. Use of omeprazole during pregnancy: no hazard demonstrated in 955 infants exposed during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2001 May; 96(1): 63–8

Nikfar S, Abdollahi M, Moretti ME, et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors during pregnancy and rates of major malformations: a meta-analysis. Dig Dis Sci 2002 Jul; 47(7): 1526–9

Ruigomez A, Garcia Rodriguez LA, Cattaruzzi C, et al. Use of cimetidine, omeprazole, and ranitidine in pregnant women and pregnancy outcomes. Am J Epidemiol 1999 Sep 1; 150(5): 476–81

Bateman DN, Colin-Jones D, Hartz S, et al. Mortality study of 18 000 patients treated with omeprazole. Gut 2003 Jul; 52(7): 942–6

Acknowledgements

The DSRU is a registered independent charity (No. 327206) that works in association with the University of Portsmouth, UK. It receives unconditional donations from pharmaceutical companies, which have no control over the conduct or the publication of studies carried out by the DSRU. The Unit has received such funds from the manufacturer of Nexium® (esomeprazole). Professor Shakir has been a member of advisory committees on other products for the manufacturer of Nexium®. Drs Davies and Wilton have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the contents of this article.

The authors thank the numerous general practitioners and the UK Prescription Pricing Division (formerly Prescription Pricing Authority) for their important participation in this study. Thank you also to Mrs Lesley Flowers, Mr Shayne Freemantle and Mrs Phyl Dudley for their assistance in the preparation of this report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Davies, M., Wilton, L.V. & Shakir, S.A.W. Safety Profile of Esomeprazole. Drug-Safety 31, 313–323 (2008). https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200831040-00005

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/00002018-200831040-00005