Parenting apps review: in search of good quality apps

Introduction

Parenthood is a period of dramatic physical, social, and psychological adjustments that are full of joy and worry for many parents. First-time parents may be particularly challenged, as they may feel unprepared to care for their infants. They may rely upon the Internet and mobile applications or “apps” for support in handling day to day parenting situations (1-3). Health care professionals and app developers have introduced numerous apps to support parenting. However, parents continue to report difficulty locating apps that meet their needs due to the proliferation of irrelevant and low-quality apps (4-7). Therefore, the purpose of this review paper was to offer a list of good quality parenting apps, available on the Google Play Store, that parents can use and health care professionals can suggest.

Contemporary parents are active users of apps to find information and support on common parenting issues such as improving infant sleep, tracking their babies’ growth and development, and sharing memorable moments (8-10). First-time parents appreciate the convenience of apps as they offer immediate assistance, day or night, when more traditional parenting supports and services are typically inaccessible. Further, apps that work offline make it easier for parents to use their features in the absence of Internet access (2,4,11). In fact, Zhao et al. (12) reported that the 24/7 access offered by apps helped mothers adjust and transition to their new role as parents.

Since the advent of personal tablets and smartphones, there are a growing number of apps available on any given topic. The Google Play and Apple app store contain 2.1 and 2 million apps respectively (13). Searching for “parenting apps” in Google resulted in over 160 million hits (https://www.google.ca/?gws_rd=ssl#q=parenting+apps). The widespread use of apps makes it an ideal platform to support parents in their parenting (12). However, the proliferation of low-quality apps creates barriers for parents in effectively utilizing apps. Lupton and Pedersen (8) reported that 12% of mothers found parenting apps unhelpful due to inaccuracies, irrelevance, and anxiety-provoking content. Unappealing design, lack of interactive features, poor functioning, and lack of credible and useful content were found to compromise app quality and deter parents from using an app. Bhandari et al. (14) found that app design affected parents’ first impressions about quality, thereby significantly encouraging or discouraging their download. Additionally, certain app features were more desirable to parents. Zhao et al. (12) reported 13 out of 21 parents rated interactive features such as reminders, calendar, keyword searches, and social networking as key reasons for using an app.

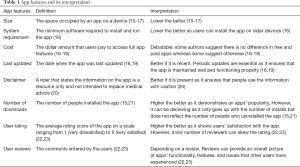

An app is a self-contained software program that comes in various sizes and features. The app is designed for a particular purpose and is downloadable from app stores to mobile devices, such as tablets and smartphones. There are a variety of attributes that users may consider when selecting an app. Reading about basic app features provided on the app description page can help parents make decisions about what to select and downloads. Each app description page is populated by the app developer and provides basic information about the app and showcases apps’ features. Basic features include size, system requirement, cost, last update, disclaimer, number of downloads, user rating and user comments (15-23). Table 1 presents definitions and interpretations of basic app features.

Full table

Understanding the aforementioned features can assist parents in identifying an appropriate app for their parenting needs. However, this is not the only consideration in searching for a good quality app. According to the research, apps that are aesthetically pleasant, easy to use, functional, engage users, and provide credible information are generally considered to be high quality (24,25). Parents face numerous challenges in search of good quality parenting apps such as insufficient information or app features, navigation issues, and undue advertisements that hinders an app use and cause frustrations.

Aims

Many researchers have identified issues with existing parenting apps (5,6,12,26) and reported that parents and health care professionals face difficulties finding good quality apps (4,7,27,28); however, there is a lack of studies suggesting quality apps that parents can use. Therefore, this paper intended to facilitate decision making among parents by offering a review of quality apps that parents can use, and health care professionals can suggest.

Methods

The Google Play Store was searched for freely available apps using prespecified eligibility criteria. First, an initial screening of all apps (n=4,300) was performed using the information available on the app store. Following this, 175 apps that met the criteria were downloaded on a device and were further screened for eligibility. Finally, quality evaluation of sixteen apps was conducted using Mobile App Rating Scale (MARS), a reliable tool specifically designed for app evaluation. Prior to the app review, the authors viewed the MARS training video available on YouTube (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=25vBwJQIOcE) as recommended by the MARS developers. The data for review was extracted from Google Play description pages (https://play.google.com/store) and the apps themselves.

Search strategy

The authors searched apps from the Google Play Store on June 1st, 2018 using the following eighteen terms: mum, mom, mommy, mama, mother, father, dad, daddy, papa, newborn, baby, infant, kid, child, children, family, parent, and parenting. The search was conducted on a public computer and none of the search restrictions were applied except free.

Eligibility criteria

The authors included apps based on the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. Apps were included that were: (I) written in English; (II) available to the general public; and (III) a self-contained product that did not necessitate add-ons or an external device to operate. Apps were excluded that were: (I) duplicates; (II) exclusively for pregnancy; (III) targeting children or parents of children above the age of one; (IV) targeting infants’ rather than parents (given screen time guidelines from Canadian Pediatric Society); (V) targeting health care professionals; (VI) focusing on diseases or conditions such as autism (study population was limited to healthy parents and healthy infants); (VII) focusing on parental dating and shopping (due to the potential risk of privacy and security such as theft and fraud); (VIII) non-relevant apps (apps focusing on food, nature, games, religion and parental greetings cards/quotes); (IX) deleted from the app store; and (X) targeting specific countries (e.g., child support apps).

Apps (n=175) that met the inclusion/exclusion criteria were downloaded onto a Samsung Galaxy 7 tablet for further screening. Apps were further excluded if they had: inadequate information/features (n=48), navigation issues (n=39), insufficient free features (n=25), lack of credible information/sources (n=24), excessive advertisements (n=19), and demanded unnecessary personal information (n=4).

App evaluation tool: MARS

A multidisciplinary team of health care professionals and app designers/developers constructed the MARS tool to effectively evaluate the quality of apps. The internal consistency is alpha =0.90, and interrater reliability intraclass correlation coefficient is 0.79 (24). MARS is available free online (https://mhealth.jmir.org/article/downloadSuppFile/3422/14733). MARS is comprised of four subscales that measure: (I) engagement—fun, interesting, customizable, interactive, and well-targeted to audience; (II) functionality—performance, ease of use, navigation, and gestural design; (III) aesthetics—layout, graphics, and overall visual appeal of the app; and (IV) information—quality, quantity and credibility of information, accuracy of app description page, and app goals. Each category is evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale (1 =inadequate, 2 =poor, 3 =acceptable, 4 =good, and 5 =excellent) or not applicable to provide a mean score for each subscale. The total mean value of all four subscales is considered the final measurement of the app quality (24).

Results

Of the 4,300 apps identified in the initial search, only 0.4% of the apps (n=16) met the quality criteria. All apps were free and available to the general public. The majority of the eligible apps were also available on the iOS platform, while only three apps were exclusively for the Android users. Most of the apps included in this review were featured in health and fitness (n=5) and parenting (n=5) categories. All of the apps (n=16) contained a privacy policy either on the app itself or on the official website; a majority (n=12) were updated within the last year, and a half (n=8) were free of advertisements or “ads”. The lowest customer star rating was 3.9/5, and the highest was 4.8/5. A majority of the apps (n=12) were rated above 4.5 by users. The number of downloads ranged from one thousand to ten million. The lowest number of downloads was for the app Babybrains developed by a neuroscientist, and the highest number of downloads was for a commercial app, BabyCenter.

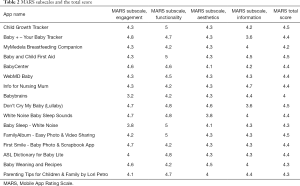

The overall highest MARS score was 4.5/5 for four apps, and the lowest was 4/5 for one app. The remaining 11 apps received ratings between 4.2 and 4.4 out of 5. The MARS subscale engagement mean was 4.3, with apps rated from 3.2 to 4.8/5. Most apps were rated high on functionality and ease of use (functionality mean score =4.6; ranging from 4.2 to 5), followed by visual appeal (aesthetic mean score =4.2; ranging from 3.8 to 4.6) and information (mean score =4.2; ranging from 3.6 to 4.7). Table 2 depicts the final scores for each subscale.

Full table

Brief overview of eligible apps

The apps covered varied aspects of parenting thus, for the ease of reporting the apps were divided into six categories according to their primary purposes such as tracking apps; information apps; sleeping-aid apps; photo sharing apps and; miscellaneous apps. The tracking apps allowed parents to track babies’ basic activities, such as feeding, voiding, and bowel movements. Information apps provided parenting information such as infant feeding, age-appropriate activities, first aid, and more. Sleeping-aid apps presented white noises and lullabies to soothe infants and induce sleep. Photo sharing apps permitted parents to share baby moments privately with loved ones. The miscellaneous app category comprised of apps that did not fit any of the categories mentioned above, such as meditation. The authors presented the comparison tables in each category, except the miscellaneous apps, for parents to select apps based on the features that matter most to them and health care professionals to recommend app based on parents’ needs.

Tracking apps

Tracking apps help parents understand their infants’ basic activity patterns, identify concerns, and report accurate data to health care professionals upon their regular and emergency visits. These apps make parenting easier by allowing sleep-deprived parents to retrieve data with a click of a button instead of using their tired mind recalling when their little one was fed last. Researchers had documented several features that make a tracking app appealing to parents (8,10,29,30) including: (I) ability to customize the app based on parents’ needs and style such as ability to add/delete activity, option to choose from automated or manual data entry, and data editing; (II) notifications/reminders for upcoming feeding and diaper change; (III) visual representation of the data through charts and graphs; (IV) synchronize or “sync” function to collaborate infant care and see real-time updates entered by other caregivers; (V) data export and sharing options and; (VI) built-in app support through chat rooms and forums.

The review included three tracking apps: Child Growth Tracker, Baby + – Your Baby Tracker, and MyMedela Breastfeeding Companion. The highest rated app in this category was the Child Growth Tracker app (4.5/5) due to the highest scores on functionally subscale 5/5 and on information subscale 4.2/5 compared to other apps in this category. The Child Growth Tracker app is simple and easy to use app that provides multiple evidenced-based scales to monitor a child’s growth.

Table 3 illustrates the comparison between the apps to help parents select one based on their needs and style preferences. For example, out of all three apps, Baby + – Your Baby Tracker has the most tracking options, as well as additional features such as white noise, lullabies, baby book, and information. This app might be more suitable for parents who prefer a multifunctional app and would like to track more than just basic activities. On the contrary, the Child Growth Tracker is solely designed for recording infants’ growth such as height, weight, head circumference, and body mass index (BMI). Over time, when the frequency of infants’ basic activities reduces some parents only like to monitor their growth by years. The MyMedela Breastfeeding Companion app was designed specifically for breastfeeding mothers to promote Medela LLC. products; however, users do not have to buy any Medela products to use the app. The app provides basic activity tracking and some information. Parents should be advised to use caution given that the information provided might be influenced by commercial gains.

Full table

Information apps

First-time parents often feel unprepared for the care of their newborn, have doubts about what to expect regarding child development and questions about infant care. Many parents have used the Internet and apps to find quick and succinct answers to their immediate concerns (1-3). Researchers have identified some characteristics that parents look for in an information app (5,6,7,12) such as: (I) credible; (II) appropriate amount of information; (III) relevant; (IV) various modes of information delivery; (V) keyword search; and (VI) discussion forums.

The review included five information apps: Baby and Child First Aid, BabyCenter, WebMD Baby, Info for Nursing Mum, and Babybrains. The top-rated app in this category was the Baby and Child First Aid app (4.5/5). The app scores highest (5/5) on functionality subscale, is easy to navigate and provides first aid information from a reputable source, Red Cross. The Info for Nursing Mum app is specifically targeted to breastfeeding mothers and can be useful for first-time parents in the first couple of months. In comparison, the Baby and Child First Aid app covers emergency information for children and parents that is useful for years to come. The BabyCenter and WebMD Baby apps offer information on various parenting concerns and include additional functions such as a baby book, whereas Babybrains app is specific to activities that enhance infants’ brain development. While Baby and Child First Aid and Info for Nursing Mum apps do not allow users to personalize the app based on the infant’s age, the other apps permit parents to customize their homepage based on their baby’s age. Table 4 shows a comparison between information apps.

Full table

Sleeping-aid apps

Sleep is a significant concern for new parents, and there is an abundance of literature available on the types and efficacy of soothing noises and lullabies to promote infant sleep (31-33). The apps presented in this paper intend to support parents in selecting the best available apps for white noises and lullabies if they choose these strategies. The authors identified key features of sleeping-aid apps that parents might find useful, including: (I) personalization options such as timer, fade out, ability to combine different sounds, record or add own sound/lullaby; (II); running in the background so parents can use their mobile device while lullabies/white noises are playing; and (III) work offline so parents can use it in the absence of the Internet.

The authors included three sleeping-aid apps: Don’t Cry My Baby (Lullaby), Baby Sleep - White Noise, and White Noise Baby Sleep Sounds. The most highly rated of the three was the Don’t Cry My Baby (Lullaby), scoring 4.5/5. While this app has more lullabies and less white noises compared to the other two, it has additional features such as animals/instruments/cars sounds and a rattle that parents can use as a distraction; however, health care professionals should caution parents about screen time guidelines if parents decide to use this feature. Table 5 provides a comparison between sleeping-aid apps.

Full table

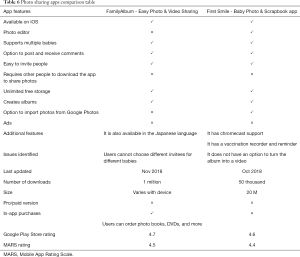

Photo sharing apps

Parenting is generally associated with an increased level of stress among parents. Sharing happy parenting moments with family and friends allow parents to prolong and intensify the positive emotions and appreciate the joy associated with parenting thus facilitating adjustments to their new role. A study of 435 parents of young children indicated individual and relational benefits of sharing positive parenting events with loved ones (34). Many researchers have reported parents use social media to feel connected with their social network and to showcase and validate their parenting practices through likes and comments (35) however, sharing identifiable information along with photos may pose privacy and security risks (36,37). Therefore, some app developers have developed private photo sharing apps as an alternative to posting photos on public platforms. These apps allow parents to share photos with people they know and can trust with their infants’ photos. There are two private photo sharing apps included in this review: First Smile - Baby Photo & Scrapbook App and FamilyAlbum - Easy Photo & Video Sharing. Both apps have similar features except FamilyAlbum - Easy Photo & Video Sharing app allows parents to order photo books online, whereas the First Smile - Baby Photo & Scrapbook App offers photo editing option. Family Album - Easy Photo & Video Sharing app was rated highest (4.5/5) in this category because of the highest score on functionality subscale (5/5). Table 6 provides a comparison between the two photo sharing apps.

Full table

Miscellaneous apps

Miscellaneous apps category contained apps that did not fit in the categories mentioned above. These apps were ASL Dictionary for Baby Lite, Baby Weaning and Recipes, and Parenting Tips for Children & Family by Lori Petro. These apps were exclusive to one particular activity such as baby sign language, baby weaning, and meditation; therefore, it was difficult to create a comparison table. The highest rated app in miscellaneous app category was ASL Dictionary for Baby Lite (4.4/5) due to the highest score on functionality subscale (4.8/5) compared to other apps in this category. The authors identified key features of these apps, and a brief overview of each app is provided in Table 7 to assist parents and health care professionals in selecting desired apps.

Full table

Discussion

In this review of free parenting apps available on the Google Play Store, the authors found only 16 (0.4%) relevant quality apps out of 4,300 apps which reflects the extent of the problem contemporary parents face in a quest of finding a good quality app. The constant increase of app use amongst parents (1-3), the proliferation of low-quality apps (4-7), and the reluctance of health care professionals to suggest an app (24,25) present a timely opportunity to offer an app review that provides a list of good quality apps that parents can use. This app review offers a brief overview of quality apps that are evaluated using MARS (24), a rigorously developed tool by a multidisciplinary team to appraise the quality of an app. The review also highlights the need for more evidence-based apps as none of the apps included in this review have trailed or tested for efficacy. This finding is similar to other studies (7,38,39).

Fathers play an important role in the development of an infant’s physical, social, and mental well-being. Similar to mother, fathers also go through uncertainty and anxiety related to infant care and require support after the birth of their child. However, it was intriguing to note that despite having four specific search terms for fathers (dad, daddy, papa, and father) none of the apps qualified for the MARS review that addresses fathers’ needs. The literature revealed a few apps such as mDad (40), Milkman (41), and DadTime (42) designed by health care professionals, especially for fathers. However, it seems that these apps are still under review or might not be developed for Android users as none of the apps came up on the Google Play Store search.

Evidenced-based apps are more scientifically robust, but they often lack user engagement and intuitive user interfaces compared to commercial apps (43,44). Commercial apps may pose privacy and security risks by leaking or selling personal data to third parties and provide content that may have influenced by commercial gains (7). However, commercial apps seem to be more popular among parents (4,7,44). For example, in this study, BabyCenter, a commercially developed app had the highest number of downloads (10 million) compared to an evidenced-based app that does not only have a low number of downloads (1,000) but also scored lowest on the MARS engagement subscale amongst all apps. Tinschert (38) presented a review of asthma apps and shared similar findings that academic apps scored lowest on MARS engagement subscale.

Implications for practice

Considering current trends of increased smartphone use, health care professionals have a responsibility to support digital literacy among parents. Health care professionals can encourage parents to look for the privacy policy of apps to ensure that personal information is not shared with the third party; to check for the source of information or Health On the Net (HON) seal, to verify the quality of health information; and to appraise apps using app evaluation tools, such as the user version of the MARS (uMARS) (45). These strategies will assist parents in identifying risks and benefits associated with the use of a particular app, thus facilitating informed decision-making regarding app use.

Several researchers have presented parenting app reviews but have limited their findings to discuss the quality issues with existing apps (5,6,12,26), thus leaving parents and health care professionals to discover the quality apps on their own. Future apps reviews should not merely focus on concerns regarding available apps but should also offer apps that are of good quality. Providing a list of quality apps that parents can use will reduce the frustrations associated with app search and will increase the utilization of good quality apps. This app review is the first phase of a project that aims at developing a website that will serve as a hub for quality parenting apps. The website will be updated frequently and will also allow parents to suggest quality apps.

Creating strategic partnerships between academic and commercial entities for future app development may result in apps that are scientifically robust and appealing to users. Research methodologies, such as the participatory design that advocates developing technology with the users, should be used in developing user-centered parenting apps. These approaches will increase parents’ uptake of academic apps and reduces the dangers associated with the use of low-quality apps. Future research should also focus on developing and disseminating apps for fathers as the involvement of fathers is a crucial component of family-centered care.

Limitations

Certain limitations need to be taken into account when considering the results and contributions of this review. The authors only included free apps available in the English language, and as a result, there is a possibility that some quality apps may have been missed. The primary author reviewed the apps independently using MARS. Although the MARS has good interrater reliability (24,38) there is a possibility that authors’ subjectivity might have impacted the scores; therefore, users are required to use caution in interpreting the findings of the review. The rapid rate at which apps develop, update, and disseminate imposes challenges to present an up-to-date review of the apps. It is likely that some of the apps’ characteristics might not be the same as the authors presented in this review.

Conclusions

Apps are increasingly becoming an essential part of technologically savvy parents’ life. However, the rapid growth of apps presents a challenge for parents and health care professionals to locate good quality apps. The authors offered a list of free 16 quality parenting apps available on Google Play Store and provided a brief overview of each app for parents, thereby facilitating selection of apps based on their style and need. The Google Play Store lacks quality apps for fathers, thus providing an opportunity for researchers to recognize the role of fathers and develop apps that geared towards supporting fathers in adjusting to their new role. Academic apps should not only focus on evidenced-based content but also include parents’ preferences and perspectives in designing future apps. Involving end users in designing and developing apps will lead to better user-centered apps available for the general population and will increase the ownership and utilization of these apps. Health care professionals should be equipped with the strategies to guide parents safe use of technology and to support technologically savvy parents in their quest to finding good quality apps.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Eleni Stroulia, Professor, Faculty of Science, University of Alberta, for her participation in the conception and design of the project as one of the supervisory committee members.

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: The abstract of this paper is approved for oral presentation at the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) National Conference & Exhibition: 2019 Council on Clinical Information Technology (COCIT). New Orleans, Louisiana, United States. The abstract will be presented by the primary author in Oct 2019.

Ethical Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

References

- Jang J, Dworkin J, Hessel H. Mothers' use of information and communication technologies for information seeking. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw 2015;18:221-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Asiodu IV, Waters CM, Dailey DE, et al. Breastfeeding and use of social media among first-time African American mothers. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs 2015;44:268-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Shorey S, Dennis C, Bridge S, et al. First-time fathers’ postnatal experiences and support needs: a descriptive qualitative study. J Adv Nurs 2017;73:2987-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hearn L, Miller M, Lester L. Reaching perinatal women online: the Healthy You, Healthy Baby website and app. J Obes 2014;2014:573928.

- Taki S, Campbell KJ, Russell CG, et al. Infant feeding websites and apps: a systematic assessment of quality and content. Interact J Med Res 2015;4:e18. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Davis DW, Logsdon MC, Vogt K, et al. Parent education is changing: a review of smartphone apps. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 2017;42:248-56. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lupton D, Pedersen S. An Australian survey of women's use of pregnancy and parenting apps. Women Birth 2016;29:368-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lupton D. The use and value of digital media for information about pregnancy and early motherhood: a focus group study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2016;16:171. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pehora C, Gajaria N, Stoute M, et al. Are parents getting it right? a survey of parents' internet use for children's health care information. Interact J Med Res 2015;4:e12. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chin K. Prospective data collection for feeding difficulties and nutrition [dissertation]. Boston, MA: Boston University, 2018.

- Mindell JA, Leichman E, Composto J, et al. Development of infant and toddler sleep patterns: real-world data from a mobile application. J Sleep Res 2016;25:508-16. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhao J, Freeman B, Li M. How do infant feeding apps in china measure up? a content quality assessment. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e186. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Number of apps available in leading app stores as of 3rd quarter 2018. (Accessed 2019 April 2). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/276623/number-of-apps-available-in-leading-app-stores/

- Bhandari U, Neben T, Chang K, et al. Effects of interface design factors on affective responses and quality evaluations in mobile applications. Comput Human Behav 2017;72:525-34. [Crossref]

- Morse S, Murugiah M, Soh Y, et al. Mobile health applications for pediatric care: review and comparison. Ther Innov Regul Sci 2018;52:383-91. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Noei E, Syer M, Zou Y, et al. A study of the relation of mobile device attributes with the user-perceived quality of Android app. Empir Softw Eng 2017;22:3088-116. [Crossref]

- Zhao S, Pan G, Zhao Y, et al. Mining user attributes using large-scale APP lists of smartphones. IEEE Syst J 2017;11:315-23. [Crossref]

- Harbach M, Hettig M, Weber S, et al. Using personal examples to improve risk communication for security and privacy decisions. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Toronto, ON, Canada; April 26–May 01, 2014.

- Brouard B, Bardo P, Bonnet C, et al. Mobile applications in oncology: is it possible for patients and healthcare professionals to easily identify relevant tools? Ann Med 2016;48:509-15. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Charbonneau DH. Health disclaimers and website credibility markers: guidance for consumer health reference in the affordable care act era. RUSQ 2015;54:30-6. [Crossref]

- Zhang P, Dong L, Chen H, et al. The rise and need for mobile apps for maternal and child health care in China: survey based on app markets. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e140. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Palomba F, Linares-Vásquez M, Bavota G. Crowdsourcing user reviews to support the evolution of mobile apps. J Syst Softw 2018;137:143-62. [Crossref]

- Genc-Nayebi N, Abran AA. Systematic literature review: opinion mining studies from mobile app store user reviews. J Syst Softw 2017;125:207-19. [Crossref]

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Mobile app rating scale: a new tool for assessing the quality of health mobile apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2015;3:e27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Golden A, Krauskopf P. Systematic evaluation of mobile apps. J Nurse Pract 2016;12:e27-8. [Crossref]

- Silva BM, Rodrigues JJ, de la Torre Díez I, et al. Mobile-health: A review of current state in 2015. J Biomed Inform 2015;56:265-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Boe Danbjørg D, Wagner L, Rønde Kristensen B, et al. Nurses' experience of using an application to support new parents after early discharge: an intervention study. Int J Telemed Appl 2015;2015:851803.

- Aitken M. Patient adoption of mHealth use, evidence and remaining barriers to mainstream acceptance. 2015. (Accessed 2019 April 2). Available online: https://www.iqvia.com/-/media/iqvia/pdfs/institute-reports/patient-adoption-of-mhealth.pdf

- Demirci JR., Bogen DL. Feasibility and acceptability of a mobile app in an ecological momentary assessment of early breastfeeding. Matern Child Nutr 2017. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang CJ, Chaovalit P, Pongnumkul S. A Breastfeed-Promoting Mobile App Intervention: Usability and Usefulness Study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- O’Loughlin H. Effect of a heart beating breathing doll on infant sleep [master's thesis]. Canterbury, New Zealand: University of Canterbury; 2018. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7e22/67f8b62db569798d97c49e49a7734c8666c0.pdf. Accessed 24 March, 2019.

- Brooks W. Putting lullabies to bed: the effects of screened presentations on lullaby practices. AJME 2016;50:83-97.

- Taheri L, Jahromi M, Abbasi M, et al. Effect of recorded male lullaby on physiologic response of neonates in NICU. Appl Nurs Res 2017;33:127-30. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Burkhart ML, Borelli JL, Rasmussen HF, et al. Cherish the good times: relational savoring in parents of infants and toddlers. Pers Relatsh 2015;22:692-711. [Crossref]

- Oeldorf-Hirsch A, Sundar S. Social and technological motivations for online photo sharing. JoBEM 2016;60:624-42.

- Brosch A. When the child is born into the internet: sharenting as a growing trend among parents on Facebook. TNER 2016;43:225-35. [Crossref]

- Benevento A. Parents frame childhood for the world to see in digital media postings [dissertation]. New York: The City University of New York, 2018.

- Tinschert P, Jakob R, Barata F, et al. The potential of mobile apps for improving asthma self-management: a review of publicly available and well-adopted asthma apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e113. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Baker TB, Gustafson DH, Shah D. How can research keep up with eHealth? Ten strategies for increasing the timeliness and usefulness of eHealth research. J Med Internet Res 2014;16:e36. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lee SJ, Walsh TB. Using technology in social work practice: the mDad (mobile device assisted dad) case study. Adv Soc Work 2015;16:107-24. [Crossref]

- White BK, Martin A, White JA, et al. Theory-based design and development of a socially connected, gamified mobile app for men about breastfeeding (milk man). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4:e81. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Encouraging Attendance and Engagement in Parenting Programs: developing a Smartphone Application with Fathers, for Fathers. 2018. (Accessed 2019 March 14). Available online: https://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/opre/b3_dadtime_brief_508.pdf

- Jake-Schoffman DE, Silfee VJ, Waring ME, et al. Methods for Evaluating the Content, Usability, and Efficacy of Commercial Mobile Health Apps. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e190. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hingle M, Patrick H. There are thousands of apps for that: navigating mobile technology for nutrition education and behavior. J Nutr Educ Behav 2016;48:213-8.e1. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Stoyanov SR, Hides L, Kavanagh DJ, et al. Development and Validation of the User Version of the Mobile Application Rating Scale (uMARS). JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2016;4:e72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Virani A, Duffett-Leger L, Letourneau N. Parenting apps review: in search of good quality apps. mHealth 2019;5:44.