Current status of asthma care in South Korea: nationwide the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service database

Introduction

Asthma is a major public health problem that affects approximately 300 million people worldwide (1). Its prevalence is estimated to be 7–10% and has continued to increase over the last half century (1-3). The economic burden of asthma is substantial, as it imposes an additional $1,907 annually for each patient and total of $18 billion are spent in the United States (4). Furthermore, asthma results in higher healthcare utilization and limited productivity, and these disadvantages are more severe in those with poor control of their asthma (5,6).

Asthma is an ambulatory care sensitive condition, in which considerable hospitalization can be avoided by high-quality primary healthcare (7). Therefore, it is important to maintain fair quality control in primary health care. Care can include assessment, treatment adjustment, and review of the treatment response (8). The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reported that asthma hospitalization rates are 98.5/100,000 in South Korea, which is considerably higher than the OECD average of 43.8/100,000 and is avoidable with high-quality primary care (9).

Pulmonary function testing (PFT) is the mainstay for diagnosing and monitoring patients with asthma, and inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are the most important medications (8,10). However, only half of patients with asthma undergo PFT at diagnosis and <20% of patients do so at follow-up (11). Other studies that targeted Asia-Pacific patients reported that only 13% of patients are treated with an ICS (12). This discrepancy between the guidelines and real-world data is crucial, as it may lead to misdiagnosis, malpractice, and dissipation of public resources. Nonetheless, no studies have revealed these quality-control factors in different types of medical institutions.

All healthcare institutions in South Korea claim medical expenses through the Health Insurance Review and Assessment Service (HIRA) (13). This organization evaluates the adequacy of medical expenses and approves insurance reimbursements from National Health Insurance, National Medical Aid, and the Korean Veterans Health Service, which support almost the entire national population. The HIRA collects patient clinical information reported by physicians for insurance claims. Therefore, clinical data of almost every patient diagnosed with asthma in the nation can be identified in the HIRA database.

In this study, we analyzed the HIRA database to assess asthma quality control in South Korea. Moreover, we investigated whether there are differences in quality control between different types of medical institutions.

Methods

Data source and selection

We analyzed the HIRA database based on insurance claims for reimbursements from all medical institutions in South Korea from July 2013 to June 2014. This database includes general demographic data, 10th revision of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10), type of medical institution, medications prescribed, and medical costs. We extracted medical information of patients with asthma from the HIRA database from July 2013 to June 2014. Inclusion criteria were: (I) age >15 years; (II) ICD-10 code for asthma (J45 or J46), as the primary or first secondary diagnosis; (III) use of asthma medication prescribed by an outpatient clinic more than once per year; (IV) or history of admission while taking a systemic steroid and at least one outpatient clinic with asthma medication.

Subjects for evaluation

The types of medical institutions included in the database were tertiary hospitals, general hospitals, hospitals, convalescent hospitals, primary health clinics, public health centers, branch offices of the public health center, and county hospitals. Oriental hospitals, dental clinics, and maternity clinics were excluded. Medical institutions that did not treat any patients with asthma during the study period were excluded. The number of patients with asthma was determined, and the medical institutions were categorized by type. We also identified the patient distributions by sex and age.

Assessment of asthma care quality

We measured performance rates of PFT in patients with asthma. We also compared the performance rates between the different types of medical institutions. PFT included the basic pulmonary function test, flow-volume curve, cardiopulmonary exercise test, peak expiratory flow rate test, and bronchial provocation test. Patients who were incapable of performing the PFT, including patients with dementia or decreased mentality or facial palsy were excluded. Medical institutions that treated <10 patients with asthma per year were excluded from the analysis.

We calculated the prescription rate for asthma medications by route of administration (oral, intravenous, patch, and inhalation) and drug category (oral corticosteroid, leukotriene receptor antagonist, methylxanthine, oral bronchodilator, patch bronchodilator, ICS, ICS plus long-acting β2-agonist, short acting β2-agonist, and short acting muscarinic antagonist). All statistical analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical statement

The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (No. KC16RESI0560).

Results

Subjects for evaluation

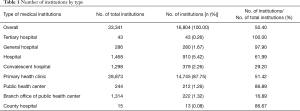

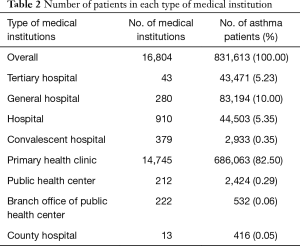

A total of 16,804 medical institutions were included, which was 50.40% of all institutions registered in the HIRA database. The number of each medical institution is presented in Table 1. Of all institutions, tertiary hospitals accounted for 0.26% and primary health clinics accounted for 87.75% of the institutions included. Every tertiary hospital in the database was included in this study, and 51.42% of primary health clinics were included.

Full table

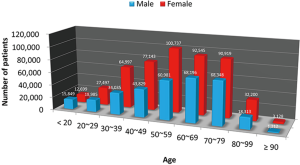

The numbers of patients treated for asthma in each medical institution type are shown in Table 2. The total number of patients with asthma was 831,613. Among them, 43,471 (5.23%) were managed in a tertiary hospital, and 686,063 (82.50%) were managed by a primary health clinic. The number of females was 501,865 (60.35%) and 481,726 (57.93%) were 50–79 years old. The most prevalent age for asthma was 50–59 years in females and 70–79 years in males. The patient distributions by age and sex are illustrated in Figure 1.

Full table

Assessment of asthma control quality

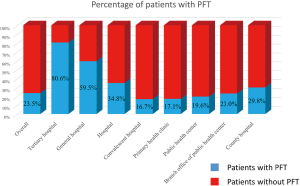

The overall pulmonary function test performance rate was 23.47%, which was highest in tertiary hospitals (80.59%) and general hospitals (59.52%) compared to that in primary health clinics (17.06%). Variation within each institution was highest in the primary health clinics and lowest in the tertiary hospitals (Figure 2).

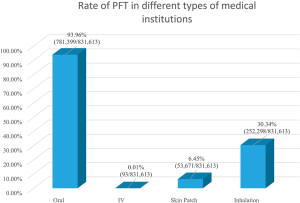

Route of drug administration was mostly oral (93.96%; 781,399/831,613; Figure 3). By contrast, inhalation agents were prescribed to only 30.34% of patients (252,298/831,613). The fewest patients were treated with intravenous drugs.

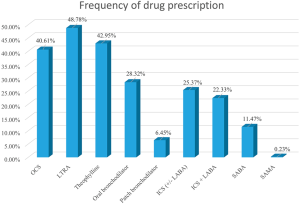

By analyzing the frequency of drug prescription by its category, the prescription rate for oral corticosteroids was 40.61%, that for leukotriene antagonists 48.78%, oral β2-agonist was 28.32%, oral theophylline was 42.95%, and ICS 25.37% (Figure 4).

Discussion

We reported nationwide asthma quality-control data in South Korea. The majority of patients were treated in primary health clinics, and only 5% of the patients were treated in tertiary hospitals. Although PFT and ICS are the most important diagnostic and treatment methods, respectively, only 23.47% of patients with asthma were assessed with PFT, and 25.37% of patients were treated with ICS (8,10). These results suggest that diagnosis and treatment of asthma remain insufficient.

Results of earlier studies correspond with those of the present study, which reported low PFT rates in the asthma population; however, these studies have reported a higher rate than that in the present study (11,14-16). A population-based study in Canada revealed that the PFT rate improved from 2006 to 2010 at both the initial diagnosis (46.8% to 52.5%) and during monitoring (16.4% to 19.1%) (11). The 2010 German Health Update (GEDA) reported that lung function in 54.1% of the asthmatic population is monitored (14). They revealed that younger patients (age, 18–54 years) and obese patients received PFT less frequently. A study of primary care in Sweden that investigated adherence to the recommended guidelines in patients with asthma (15) revealed that 33% of patients underwent PFT at the initial diagnosis, and 60% of patients underwent the testing during follow-up. Our results indicate that despite the fact that spirometry is crucial in the diagnosis and monitoring of patients with asthma, its underutilization is unsatisfactory, even compared to previous studies. Furthermore, the pulmonary function test rate in primary health clinics was much lower than that in health clinics, which may be due to a lack of spirometry equipment.

In the present study, oral agents were used in 93.96% of patients with asthma, which is strikingly high regarding the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines, suggesting that inhalation agents are the preferred control choice options (8). In addition, oral corticosteroids were used in 40.61% of patients, which is recommended in step 5. By contrast, ICS were used in only 25.37%, which is substantial in step higher than 1. More than half of patients with asthma are suboptimally controlled, indicating maltreatment of patients with asthma in South Korea (17). Only 13% of Asia-Pacific patients with asthma in the 2003 Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific (AIRIAP) study were prescribed an ICS (12). In a Canadian study, researchers reported that the ICS prescription rate increased from 2006 to 2010 (72.9% to 76.6%) (11). In addition, ICS therapy was used by 38.4% of patients with asthma in the GEDA study, and younger patients had a lower prescription rate (31.6% vs. 50.3%) (14). Our results suggest that adherence to asthma treatment guidelines is higher in South Korea compared to that in the Asia-Pacific study, but poorer compared to European studies.

We analyzed the South Korean insurance claims database in 2013, which covers almost every patient in the nation (16,804 medical institutions and 831,613 patients). This is a large nationwide dataset that shows difference between the guidelines and real-world practice. Patients with asthma were categorized by the medical institutions that they had visited. Most patients were treated in primary health clinics rather than tertiary or general hospitals, which may not be equipped to offer PFT or other diagnostic methods. This may be the reason for the poor asthma quality control. Therefore, a national program may be crucial for asthma management in South Korea. The National Asthma Program conducted in Finland from 1994 to 2004 substantially reduced the morbidity and social burden of asthma (18).

Several limitations of this study should be mentioned. First, this was an observational retrospective study, and several biases may be present due to its study design. Second, the HIRA database does not include any information on the asthma control state of each patient. Only a short acting β2-agonist may be sufficient and no controller may be needed for patients at step 1 of the GINA guidelines (8). However, less than half of patients with asthma are in the mild intermittent asthma category and may have no need for an ICS (19). Our results still suggest a lower prescription rate for ICS regarding these data. Third, although this study was based on one of the largest nationwide databases, we investigated only 1-year of the dataset. It is necessary to analyze these data over the long-term in subsequent studies. Fourth, there may be some issues on the accuracy of the asthma diagnosis as a result of characteristics of the HIRA database. We diagnosed patients with asthma based on doctors’ decisions and reports but neglected objective diagnostic measures, such as clinical symptoms and pulmonary function tests. Therefore, serial results must be investigated in subsequent years in the same data. Finally, as this study extracted the patients’ data from HIRA database by ICD-10 code and prescription code, we could not specify the performance of PFT as initial diagnosis or follow-up monitoring.

Conclusions

We investigated the large 2013 HIRA nationwide database to assess asthma quality control in South Korea. Most patients with asthma were treated in primary health clinics not general or tertiary hospitals. PFT was underutilized, and the ICS prescription rate was insufficient.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by HIRA (Join Project on Quality Assessment Research).

Footnote

Conflicts of Interest: CK Rhee received consulting/lecture fees from MSD, AstraZeneca, Novartis, GSK, Takeda, Mundipharma, Sandoz, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Teva-Handok. Others have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Statement: The study was approved by Institutional Review Board of the Catholic University of Korea, Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital (No. KC16RESI0560).

References

- Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, et al. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy 2004;59:469-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Anandan C, Nurmatov U, van Schayck OC, et al. Is the prevalence of asthma declining? Systematic review of epidemiological studies. Allergy 2010;65:152-67. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kay AB. Allergy and allergic diseases. First of two parts. N Engl J Med 2001;344:30-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Sullivan PW, Ghushchyan VH, Slejko JF, et al. The burden of adult asthma in the United States: evidence from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011;127:363-369.e1-3.

- Sullivan PW, Slejko JF, Ghushchyan VH, et al. The relationship between asthma, asthma control and economic outcomes in the United States. J Asthma 2014;51:769-78. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Williams SA, Wagner S, Kannan H, et al. The association between asthma control and health care utilization, work productivity loss and health-related quality of life. J Occup Environ Med 2009;51:780-5. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibson OR, Segal L, McDermott RA. A systematic review of evidence on the association between hospitalisation for chronic disease related ambulatory care sensitive conditions and primary health care resourcing. BMC Health Serv Res 2013;13:336. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- GINA Guideline, 2016. Available online: http://ginasthma.org/

- OECD. Health at Glance 2015. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/

- Kim DK, Park YB, Oh YM, et al. Korean Asthma Guideline 2014: Summary of Major Updates to the Korean Asthma Guideline 2014. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul) 2016;79:111-20. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- To T, Guan J, Zhu J, et al. Quality of asthma care under different primary care models in Canada: a population-based study. BMC Fam Pract 2015;16:19. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lai CK, De Guia TS, Kim YY, et al. Asthma control in the Asia-Pacific region: the Asthma Insights and Reality in Asia-Pacific Study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;111:263-8. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Health Insurance Review and Assessment Services. Available online: http://www.hira.or.kr/eng/index.html

- Steppuhn H, Langen U, Mueters S, et al. Asthma management practices in adults--findings from the German Health Update (GEDA) 2010 and the German National Health Interview and Examination Survey (DEGS1) 2008-2011. J Asthma 2016;53:50-61. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Weidinger P, Nilsson JL, Lindblad U. Adherence to diagnostic guidelines and quality indicators in asthma and COPD in Swedish primary care. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 2009;18:393-400. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gershon AS, Victor JC, Guan J, et al. Pulmonary function testing in the diagnosis of asthma: a population study. Chest 2012;141:1190-1196. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Braido F, Brusselle G, Guastalla D, et al. Determinants and impact of suboptimal asthma control in Europe: The International Cross-Sectional And Longitudinal Assessment On Asthma Control (LIAISON) study. Respir Res 2016;17:51. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Haahtela T, Tuomisto LE, Pietinalho A, et al. A 10 year asthma programme in Finland: major change for the better. Thorax 2006;61:663-70. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Fuhlbrigge AL, Adams RJ, Guilbert TW, et al. The burden of asthma in the United States: level and distribution are dependent on interpretation of the national asthma education and prevention program guidelines. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;166:1044-9. [Crossref] [PubMed]