With 320 film and television productions shooting in the state in 2016, Atlantans are growing accustomed to seeing their neighborhoods become Hollywood backdrops.

It certainly generates revenue for the state.1 In 2016, more feature films were shot in Georgia than in any other state, but do media producers consider Atlanta a creative haven or just an inexpensive place to shoot a project?2 Assessing Atlanta’s reputation in the media landscape was one of the reasons that Amelia Arsenault and I founded the Atlanta Media Project at Georgia State University. The Atlanta Media Project is a research collective offering tools, analysis, and events that highlight the cultural implications of the region’s evolving media ecology. Our academic careers are dedicated to examinations of the media industries and new media technology. The Atlanta Media Project is a platform for translating our research for a broader audience. On our website, we produce interactive maps, infographics, company profiles, and community-building projects that can inform public policy and support the development of Atlanta’s creative communities.

Our efforts work in tandem with Georgia’s investment in media production. In 2005, the Georgia legislature passed the Georgia Entertainment Industry Investment Act to encourage media production in the state.3 Since then, the incentive was enhanced4 and expanded5 offering up to a 30 percent tax credit for production and post-production costs on projects completed in Georgia. Georgia is far from the first state to pass a media related tax incentive. In fact, in 2009, forty-four states offered a film tax incentive.6 But by 2016, ten states had ended their incentives and several others had tightened requirements and capped annual spending amid criticism that it was an irresponsible use of taxpayer money.7

Indeed, after conducting extensive research on entertainment industry tax incentives, particularly in Louisiana, media and communications scholars Vicki Mayer and Tanya Goldman, concluded that the incentives are often little more than “Hollywood handouts.”8 While most of the debate about the tax incentives focuses on the financial impact, we focus on the cultural issues raised by Atlanta’s investment in entertainment and media. That is, though it is exciting to see Iron Man in Woodruff Park, what is the cultural value of Atlanta supporting Marvel’s cinematic universe? And should tax dollars be redirected to projects that are actually set in Atlanta instead?

Media Culture & Media Capitals

There is a major difference between a place that substitutes for other locations and a place with a distinct media culture. Film and media studies scholar Michael Curtin writes about the financial and cultural factors that make certain places “media capitals.”9 These places have unique production logics that mediate the flow of culture around the world. However, the status of a media capital is also fluid as investment capital, creative labor, and audience tastes change over time.

Curtin points to three factors that have historically distinguished media capitals. The first is a recognizable style that is meaningful to a regional and diasporic audience. At the Atlanta Media Project, we have been studying press coverage that attempts to define Atlanta’s distinct cultural style. For a time, the undead got most of the headlines thanks to the success of Zombieland, The Walking Dead, and the Vampire Diaries.10 Historically, Turner Broadcasting defined Atlanta as the capital of the South, best exemplified by the short-lived cable network Turner South.11 Atlanta’s reputation as “Black Hollywood” is particularly potent thanks to the enduring success of Tyler Perry Studios and recent award winning cable programs like Atlanta.12

Film studies scholar Serra Tinic has argued that tax incentives for “runaway production,” media projects that leave Hollywood to film in places that offer better financial incentives can lead to the development of indigenous media production and a cultural identity.13 It is not a matter of one identity rising above another but rather the relationship between indigenous productions and visiting productions that matters. At the Atlanta Media Project, we analyze this relationship and identify the narratives that are defining Atlanta’s media production culture.

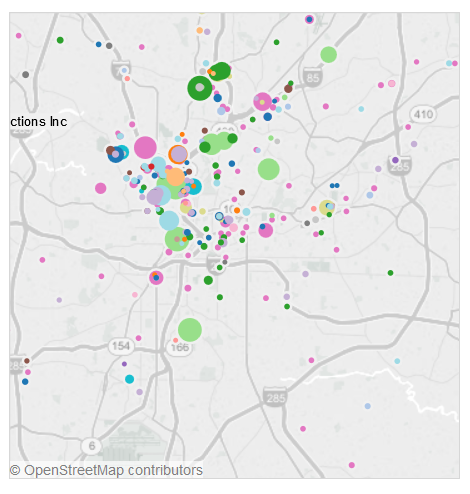

The presence of robust and sustainable creative communities is the second marker of a media capital. Atlanta’s affordability and proximity to the world’s busiest airport have proven enticing to artists, filmmakers, and tradespeople.14 In the earliest days of the Atlanta Media Project, we mapped creative clusters throughout the state in order to provide a tool for creative workers and academics interested in cultural geography. We see our efforts as part of the broader commitment of Georgia’s universities and community organizations to support our creative industries.15 Also vital, is the work of the Georgia Department of Economic Development and IATSE Local 479, which provide advocacy and support for creative workers. The state legislature has further demonstrated its dedication to expanding the labor force by collaborating with local universities to develop the Georgia Film Academy, a certificate program designed to fill vital production roles.16The final factor that makes a city a media capital is the presence of investment capital and infrastructure. Charlotte remains the financial center of the South but thanks to its proximity to Atlanta, some believe sprawl will bring the two cities together.((Rebecca Burns, “Behold the sprawl of 2060, when Atlanta and Charlotte finally converge,” Atlanta Magazine. July 25, 2014. http://www.atlantamagazine.com/news-culture-articles/behold-the-sprawl-of-2060-when-atlanta-and-charlotte-finally-converge/.) Until that happens, Georgia is focused on developing its media infrastructure, especially soundstage capacity.

When the tax incentive was passed in 2005, Atlanta only had enough capacity for a couple of major film projects at a time.17 Georgia now offers over twenty completed or planned studios.18 The crown jewel is Pinewood Atlanta Studios, which serves as the home base for Marvel’s cinematic universe. Soundstage capacity is important but it does not guarantee production longevity. In order to assess the cultural value of these companies the Atlanta Media Project has developed profiles of significant studios, infrastructure, and media companies.

Building a Brand

Being a media capital is not just about meeting benchmarks, it is also about establishing a presence in the cultural imagination of media professionals. Media studies scholar Aynne Kokas uses the term “brandscape” to describe the way that infrastructure and creative communities combine to produce an industry reputation.19 Improving Atlanta’s brand is the goal of our latest initiative the Atlanta Mobile Music project. Based on the research for my forthcoming book, the project is in an attempt to foster community through commuters’ shared love of music. In the course of my research, I found that people see their commute as a key moment in the day to connect with friends and loved ones. While mobile devices have made the commute a moment for socializing, people do not typically use them to engage with their fellow commuters.

We are asking commuters to contribute to a communal playlist that provides a glimpse of the music taste of their fellow commuters. We believe that community building efforts like this are at the heart of developing a brand that will be attractive to creative workers. In the end, it is the development of a distinct media culture that makes a media capital different from a tax shelter. The Atlanta Media Project will be producing research and looking for partnerships to ensure that Atlanta maintains its status as a media capital. Hopefully our project can help sustain the cultural momentum created by Tyler Perry’s studio expansion, the Georgia Film Academy’s education initiatives and Pinewood Studios’ planned arts community and help achieve this goal.

Citation: Tussey, Ethan. “An Emerging Media Capital or Just An Inexpensive Filming Location?: Exploring Atlanta’s Evolving Media Ecology.” Atlanta Studies. August 15, 2017. https://doi.org/10.18737/atls20170815.

Notes

- Governor Nathan Deal Press Release, “Deal: Film industry generates $9.5 billion for Georgia’s economy,” Office of the Governor, Georgia.gov, July 10, 2017. https://gov.georgia.gov/press-releases/2017-07-10/deal-film-industry-generates-95-billion-georgia%E2%80%99s-economy.[↩]

- Mia Galuppo, “Feature Film Production in Georgia Outpaced California Last Year, Study Says,” Hollywood Reporter, May 23, 2017. http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/feature-film-production-georgia-outpaced-california-last-year-study-says-1006912.[↩]

- Georgia General Assembly, H.B. 539, Georgia Entertainment Industry Investment Act, Regular Session 2005-2006.[↩]

- Georgia General Assembly, H.B. 1100, Income Tax Credit; Qualified Film, Video, or Digital Productions, Regular Session 2008.[↩]

- Georgia General Assembly, H.B. 1027, Revenue and Taxation; Tax Credit for Film or Video Production in Georgia, Regular Session 2011-2012.[↩]

- Oronde Small, and Laura Wheeler, “A Description of the Film Tax Credit and Film Industry in Georgia,” Andrew Young School Fiscal Research Center, Policy Brief, Georgia State University, February 23, 2016, p2.[↩]

- National Conference of State Legislatures, “State Film Production Incentives and Programs,” June 13, 2016. http://www.ncsl.org/research/fiscal-policy/state-film-production-incentives-and-programs.aspx.[↩]

- Vicki Mayer and Tanya Goldman, “Hollywood Handouts: Tax Credits in the Age of Economic Crisis,” Jump Cut: A Review of Contemporary Media, No. 52, Summer 2010, p5.[↩]

- Michael Curtin. “Media Capital: Towards the Study of Spatial Flows,” International Journal of Cultural Studies, 6, 2 (June 2003): 202-28.[↩]

- Robbie Brown, “Zombie Apocalypse? Atlanta Says Bring It On,” New York Times, October 18, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/19/us/zombie-apocalypse-in-atlanta.html.[↩]

- Richard Katz, “Turner, Fox compete for South,” Variety, June 16, 1999. http://variety.com/1999/biz/news/turner-fox-compete-for-south-1117503151/.[↩]

- Neela Banerjee, “Hotlanta: Is the Dirty South Really the Land of Milk and Honey?” The Root, June 7, 2010. http://www.theroot.com/hotlanta-is-the-dirty-south-really-the-land-of-milk-an-1790879782.[↩]

- Serra Tinic, On Location: Canada’s Television Industry in a Global Market. (University of Toronto Press, 2005).[↩]

- Kim Severson, “Stars Flock to Atlanta, Reshaping a Center of Black Culture,” New York Times, November 26, 2011 http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/26/us/atlanta-emerges-as-a-center-of-black-entertainment.html.[↩]

- Universities and cultural organizations throughout Georgia offer support to local creative communities including: Savannah College of Art and Design aTVfest, Atlanta Film Festival, BronzeLens Film Festival, Atlanta Jewish Film Festival, Atlanta Gamer Society, Georgia State University’s Creative Media Industries Institute, Women in Film & Television Atlanta, and Georgia Production Partnership to name a few.[↩]

- Martha Dalton, “Georgia Film Academy Helps Fill Industry’s Workforce Gap,” WABE, July 12, 2017. http://news.wabe.org/post/georgia-film-academy-helps-fill-industry-s-workforce-gap.[↩]

- J. Scott Trubey and Jennifer Brett, “Georgia speaks to Hollywood’s bottom line,” Atlanta Journal Constitution, July 29, 2013. http://www.myajc.com/business/georgia-speaks-hollywood-bottom-line/zEi6lpep0IAjXXPkxTx7YK/.[↩]

- Georgia studios include: Ambient Plus Studio, Atlanta Film Studios Paulding County, Atlanta Media Campus, Atlanta Metro Studios, Blackhall Studios, CineDome Studios, Cinema South Studios, Covington Studios, EUE/Screen Gems, Founders Studios, Lake City Crossing Sound Stage, Mailing Avenue Stageworks, North Atlanta Studios, PC&E, Pinewood Atlanta Studio, Raleigh/Riverwood Studios, Third Rail Studios, Turner Studios, Tyler Perry Studios[↩]

- Aynne Kokas. Hollywood Made in China. (Univ of California Press, 2017).[↩]