Abstract

Chromium poisoning among leather tanners has long been known. The workers have been found to suffer from ulcers, allergic dermatitis, lung cancer, and liver necrosis due to prolonged contact with chromium salts. One of the highly catastrophic incidences of lung cancer as a result of inhaling dust containing Cr (VI) was reported in 1960 from the Kiryama factory of the Nippon-Denko concern on the island of Hokkaido, Japan.

Pollution of water resources, both surface and underground, by indiscriminate discharge of spent wastes of chromium-based industries has become a serious global concern, for it has created an acute scarcity of safe drinking water in many countries. In August 1975 it was observed that underground drinking water in Tokyo near the chromium (VI))-containing spoil heaps contained more than 2000 times the permissible limit of chromium. In Ludhiana and Chennai, India, chromium levels in underground water have been recorded at more than 12 mg/L and 550–1500 ppm/L, respectively.

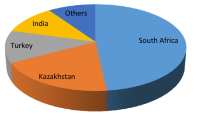

Chromium is widely distributed in nature, occupying 21st position in the index of most commonly occurring elements in the earth’s crust. Chromium occurs in nature in the form of a compound (chromium + oxygen + iron) known as “chromite.” The geographical distribution of chromite mines is uneven. Over 95% of economically viable chromite ores are situated in the southern part of Africa. Its annual global production is ca. 9 million tons, mainly mined in the former Soviet Union, Albania, and Africa. In India, over 90% of chromite deposits are located in Sukinda Valley of Orissa.

Chromium occurs in several oxidation states, ranging from Cr2+ to Cr6+, with trivalent and hexavalent states being the most stable and common in the terrestrial environment. Chromium (III) is used for leather tanning because it forms stable complexes with amino groups in organic material. In the presence of excessive oxygen, chromium (III) oxidizes into Cr (VI), which is highly toxic and more soluble in water than are other forms. Chromium (VI) can easily cross the cell membrane, whereas the phosphate-sulphate carrier also transports the chromite anions. On the other hand, Cr (III) does not utilize any specific membrane carrier and hence enters into the cell through simple diffusion. The diffusion is possible only after the formation of appropriate lipophilic ligands.

Use of chromium as industrial material was discovered only 100 years ago. It was used for the first time in the production of corrosion-resistant steel (stainless steel) and coatings. Subsequently, chromium was widely deployed in various industries; namely, electroplating, dyes and pigments, textiles, photography, and wood processing. The tanning industry is one of the major users of chromium (III) salts. During leather processing the conversion of putrefactive proteinaceous matter, skin, into non-putricible is carried out by the treatment of chromium sulphate solution. According to an estimate, ca. 32 tons of chromium sulphate salts are used annually in Indian tanneries. As a result of unplanned disposal of spent tannery wastes, ca. 2000–3200 tons of chromium as element escapes into the environment. This has raised severe ecological concern and reduced the forest cover considerably.

Aquatic vascular plants play an important role in the uptake, storage, and recycling of metals. The uptake of metals depends on the chemical form present in the system and on the life form of the macrophytes (floating, free floating, well rooted, or rootless). The free-floating species (Eichhornia, Lemna, Pistia) absorb elements through the roots/leaves, whereas the rootless speciesCeratophyllum demersum absorbs mainly through the finally divided leaves.

Submerged species showed higher chromium accumulation than do floating and emergent ones. The order is:Elodea canadensis > Lagarosiphon major > Potamogeton crispes > Trapa natans > Phragmitis communis. Roots of water hyacinth (Eichhornia crassipes) showed an accumulation of 18.92 μmol (g dry tissue wt-1) Cr. AlthoughCeratophyllum demersum andHydrodictyon reticulatum showed lower levels of chromium accumulation, their bioconcentration factor values were very high.

Floating-species duckweeds (Lemna, Spirodela) are potential accumulators of heavy metals. They have bioconcentrated Fe and Cu, as high as 78 times their concentration in wastewater. Duckweeds have also shown the ability to accumulate chromium substantially. Although duckweeds attain higher concentrations of chromium in their tissues than do other macrophytes, their bioconcentration factor (BCF) values were much lower than those reported in other aquatic species.

A moderate accumulation of chromium has been found in emergent species. Plants ofScirpus validatus andCyperus esculentus accumulated 0.55 kg and 0.73 kg-1 Cr, respectively. InBacopa monnieri andScirpus lacustris accumulations of 1600 and 739 μg g-1 dw Cr, respectively, have been reported when exposed to 5 mg L-1 Cr for 168 hours in solution culture. The accumulation of Cr was greater in the root than the shoot. Higher accumulations of chromium in roots and least in shoots of emergent species have also been recorded.

Phytotoxicity of chromium in aquatic environment has not been studied in detail. The mechanism of injury in terms of ultrastructural organization, biochemical changes, and metabolic regulations has not been elucidated. It has been pointed out that while considering the toxicity of heavy metals, a distinction should be made between elements essential to plants and metals that have no proven beneficial biochemical effects. For example, an increased level of chromium may actually stimulate growth without being essential for any metabolic process. In aquatic species—namely,Myriophyllum spicatum— the maximum increase in shoot length was found at 50 μgl-1 Cr. Higher concentrations up to 1000 μ gl-1 caused an almost linear reduction both in shoot weight and length. Duckweeds showed relatively greater tolerance to chromium. However, an inhibition of growth inSpirodela andLemna was found at 0.02 mM and 0.00002 mM Cr concentrations, respectively. Mortality ofL. aequinoctialis was found at 0.005 mM Cr and higher concentrations. The effective chromium concentrations (EC-50) for some aquatic species have been reported as follows:Lemna minor, 5.0 mg L-1, 14 days EC;L. Paucicostata, 1.0 mg L-1, 20 days EC;Myriophyllum spicatum, 1.9 mg L-1, 32 days EC; andSpirodela polyrrhiza, 50 mg L-1, 14 days EC.

Chromium toxicity on biochemical parameters showed a reduction in photosynthetic rate at 50 μgl-1 Cr inMyriophyllum spicatum. Decrease in chlorophyll and protein contents were also recorded inNajas indica, Vallisneria spiralis, andAlternanthera sessilis with an increase in chromium concentration. InLimnanthemum cristatum, a slight reduction in chlorophyll and almost no change in control were found due to chromium toxicity. Submerged species (Ceratophyllum demersum, Vallisneria spiralis) and an emergent one (Alternanthera sessilis) showed decreases in chlorophyll as well as in protein contents when treated with chromium.

Chromium-induced morphological and ultrastructural changes have been reported in several aquatic vascular plants: InLemna minor andCeratophyllum demersum, chromium-induced changes in chloroplast fine structure disorganized thylakoids with loss of grain and caused formation of many vesicles in the chloroplast. Chromium (VI) has caused stunting and browning of roots produced from the chromium-treated excised leaves ofLimnanthemum cristatum. At 226 μg/g Cr dry wt leaf tissue concentration, development of brown coloration in the hydathodes of juvenile leaves ofLimnanthemum cristatum is a characteristic chromiuminduced alteration.

Aquatic vascular plants and algae may serve as effective bioindicators in respect to metals in aquatic environments. Chromium-induced morphological and ultrastructural changes inLimnanthemum cristatum have significant indicator values and could be used for assessing the level of chromium in ambient water.Wolffia globosa, a rootless duckweed, showed substantial chromium accumulation and high concentration factor (BCF) value at very low ambient chromium concentrations, suggesting its feasibility in detecting chromium pollution in water resources. Methylene blue-stained cells ofScenedesmus acutus become uniformly dark blue during chromium (VI) treatment. This may serve as an indicator of chromium pollution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature Cited

Antonovics, J., A. D. Bradshaw &R. D. Turner. 1971. Heavy metal tolerance in plants. Adv. Ecol. Res. 7: 2–85.

Arisz, W. H. 1960. Translocation of salts inVallisneria leaves. Bull. Res. Coune. Israel 8D: 247–257.

Barcelo, J., Ch. Poschenrieder &B. Gunse. 1985. Effect of chromium VI on mineral element composition of bush beans. J. Pl. Nutrition 8(3): 211–217.

—,B. Gunse &C. Poschenreider. 1986. Chlorophyll and carotenoids content ofPhaseolus vulgaris in relation to mineral disorders induced by chromium (VI) supply. Photosynthetica 20: 245–249.

Barsdate, R. J., M. Nebert &C. P. McRoy. 1974. Lagoon contribution to sediments and water of the Bearing Sea. Pp. 553–576in D. W. Hood & E. J. Kelley (eds.), Oceanography of the Bering Sea. Institute of Marine Science, Univ. of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Bassi, M., M. G. Corradi &M. Realine. 1990. Effects of chromium (VI) on two fresh water plants,Lemna minor andPistia stratiotes, 1. Morphological observations. Cytobios 62: 27–38.

Baszynski, T., M. Król &D. Wolinska. 1981. Photosynthetic apparatus ofLemna minor L. as affected by chromate treatment. Pp. 111–121in G. Akoyunoglou (ed.), Photosynthesis, II. Electron transport and photophosphorylation. George Balaban International Science Service, Philadelphia.

Baudo, R. &P. G. Varini. 1976. Copper, manganese and chromium concentrations in five macrophytes from the delta of River Toce (northern Italy). Mem. Ist. Ital. Idrobiol. 33: 305–324.

—,G. Galanti, P. Guilizzoni &P. G. Varini. 1981. Relationships between heavy metals and aquatic organisms in the Lake Mezzola hydrographic system (northern Italy), 4. Metal concentrations in six submerged aquatic macrophytes. Mem. Ist. Ital. Idrobiol. 39: 203–225.

Bowen, H. J. M. 1979. Environmental chemistry of the elements. Academic Press, London.

Boyed, C. E. 1970. Vascular aquatic plants for mineral nutrient removal from polluted waters. Econ. Bot. 24: 95–103.

Cary, E. E., W. H. Allaway &O. E. Olson. 1997. Control of chromium concentrations in food plants, I. Absorption and translocation of chromium by plants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 25(2): 300–304.

Chandra, P. &P. Garg. 1992. Absorption and toxicity of chromium and cadmium inLimnanthemum cristatum Griseb. Sci. Total Environ. 125: 175–183.

—,R. D. Tripathi, U. N. Rai, S. Sinha &P. Garg. 1993. Biomonitoring and amelioration of non point source pollution in some aquatic bodies. Water Sci. & Technol. 28(315): 323–326.

Clark, J. R., J. R. Vanhassel, R. B. Nicholson, D. S. Cherry &J. Carins Jr. 1981. Accumulation and depuration of metals by duck-weed (Lemna perpusilla). Ecotoxicol. & Environ. Safety 5: 87–96.

Corradi, M. G. &M. Bassi. 1987. Morphological alterations induced by Cr6+ in fresh water plants. 14th Int. Bot. Congr., Berlin. (Abstract)

— &G. Gorbi. 1993. Chromium toxicity in two linked trophic levels, II. Morphophysiological effects onScenedesmus acutus. Ecotoxicol. & Environ. Safety 25: 72–78.

—,A. Bianchi &A. Albasini. 1993. Chromium toxicity inSalvia sclarea, I. Effects of hexavalent chromium on seed germination and seedling development. Environ. & Exp. Bot. 33(3): 405–413.

Cowgill, U. M. 1974. Hydrogeochemistry of Linsley Pond, North Bradford, Connecticut, III. The chemical composition of the aquatic macrophytes. Arch. Hydrobiol., Suppl. 45: 1–119.

Cranston, R. E. &J. W. Murray. 1978. The determination of chromium species in natural waters. Anal. Chim. Acta 99: 275–282.

Denny, P. 1972. Sites of nutrient absorption in aquatic macrophytes. J. Ecol. 60: 819–829.

Drifmeyer, J. E., G. W. Thayer, F. A. Cross &J. C. Zieman. 1980. Cycling of Mo, Fe, Cu and Zn by eelgrass,Zostera marina L. Am. J. Bot. 67: 1089–1096.

Dubey, C. S., B. K. Sahoo &N. R. Nayak. 2001. Chromium (VI) in waters in parts of Sukinda chromite valley and health hazards, Orissa, India. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 67: 541–548.

Dykyjova, D. 1979. Selective uptake of mineral ions and their concentration factors in aquatic higher plants. Folia Geobot. Phytotax. 14: 267–325.

Filbin, G. J. &R. A. Hough. 1979. The effects of excess copper sulphate on the metabolism of the duckweedLemna minor. Aquat. Bot. 7: 79–86.

Forstner, U. &G. T. W. Wittmann. 1979. Metal pollution in aquatic environment. Springer Verlag, Berlin.

Francko, D., L. Delay &S. Al-Hamdani. 1993. Effect of hexavalent chromium on photosynthesis rates and petiole growth inNelumbo lutea seedlings. J. Aquat. Plant Managern. 31: 29–33.

Frazier, J. M. 1972. Current status of knowledge of the biological effects of heavy metals in the Chesapeake Bay. Chesapeake Sci., 13 (suppl.): 149–153.

Gallagher, J. L. &H. V. Kibby. 1980. Marsh plants as victors in trace metal transport in Oregon tidal marshes. Am. J. Bot. 67: 1069–1074.

Gardner, W. S. 1980. Salt marsh creation: Impact of heavy metals. Pp. 126–131in J. C. Lewis & E. W. Bunce (eds.), Rehabilitation and creation of selected coastal habitats: Proceedings of a workshop. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Biological Services, Washington, D.C.

Garg, P. &P. Chandra. 1990. Toxicity and accumulation of chromium inCeratophyllum demersum L. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 44: 473–478.

—. 1994. The duckweedWolffia globosa as an indicator of heavy metal pollution: Sensitivity to Cr and Cd. Environ. Monitoring & Assessment 29: 89–95.

— &S. Devi. 1994. Chromium (VI) induced morphological changes inLimnanthemum cristatum Griseb.: A possible bioindicator. Phytomorphology 44(3–4): 201–206.

Gauglhofer, J. &V. Bianchi. 1991. Chromium. Pp. 853–861in E. Merian (ed.), Metals and their compounds in the environment. VCH, Weinheim, Germany, and New York.

Gaur, J. P., N. Noraho &Y. S. Chauhan. 1994. Relationship between heavy metal accumulation and toxicity inSpirodela polyrrhiza L. Schleid andAzolla pinnata R. Br. Aquat. Bot. 49: 183–192.

Gerth, J., R. Wienberg & U. Frostner. 1991. Chromium in contaminated soil: Bound forms and chromium immobilization by ferrous iron. Pp. 1: 54–57 in J. G. Farmer (ed.), Heavy metals in the environment. International Conference on Heavy Metals in the Environment, Edinburgh, Scotland.

Gommes, R. &H. Muntau. 1975. La Distribution de quelques metaux lourds (Zn, Cu, Cr, NI1, Mn, Co) dans la zone littorale des bassins sud et de Pallanza du lac Mageur. Mem. Ist. Ital. Idrobiol. 32: 245–259.

—. 1981. Determination in situ des vitesses d’absorption de mentaux lourd par les macrophytes du lago Maggiore. Mem. Ist. Ital. Idrobiol. 38: 347–377.

Guilizzoni, P. 1975. Manganese, copper and chromium content in macrophytes of Lake Endine (northern Italy). Mem. Ist. Ital. Idrobiol. 31: 313–332.

—. 1991. The role of heavy metals and toxic materials in the physiological ecology at submerged macrophytes. Aquat. Bot. 41: 87–109.

-,M. S. Adams & N. McGaffey. 1984. The effect of chromium on growth and photosynthesis of a submerged macrophyte,Meriophyllum spicatum. Pp. 90–96in L. Rasmussen (ed.), Ecotoxicology: Proceedings of the Third Oikos Conference. Ecological Bulletins, Stockholm.

Gupta, M., S. Sinha &P. Chandra. 1994. Uptake and toxicity of metal inScirpus lacustris L. andBacopa monnieri L. J. Environ. Sci. Health (A 29) 10: 2185–2202.

Heumann, H. G. 1987. Effects of heavy metals on growth and ultrastructure ofChara vulgaris. Protoplasma 136: 37–48.

Huffmann, E. W. D. J. R. &W. H. Allaway. 1973. Growth of plants in solution cultures containing low levels of chromium. Pl. Physiol. 52: 72–75.

Hutchinson, G. E. 1975. A treatise on limnology, III. Limnological botany. Wiley Interscience, London.

Hutchinson, T. C. &H. Czyrska. 1975. Heavy metal toxicity and synergism to floating aquatic weeds. Verh. Intern. Verein Limnol. 19: 2102–2111.

Jacobs, J. H. 1992. Treatment and stabilization of a hexavalent chromium containing waste material. Environ. Progress 11(2): 123–126.

Jain, S. K., P. Vasudevan &N. K. Jha. 1989. Removal of some heavy metals from polluted water by aquatic plants: Studies on duckweed and water velvet. Biol. Wastes. 28: 115–126.

Jana, S. 1988. Accumulation of Hg and Cr by three aquatic species and subsequent changes in several physiological and biochemical plant parameters. Water, Air, Soil Pollut. 38: 105–109.

Khasim Imam, D. &N. V. Nanda Kumar. 1989. Environmental contamination of chromium in agricultural and animal products near a chromate industry. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 43: 742–746.

King, J. M. &S. K. Coley. 1984. Toxicity of coal distillates toSpirodella polyrrhiza. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 23: 220–224.

Kumaresan, M. &P. Riyazuddin. 1991. Chemical speciation of trace metals. Res. J. Chem. Environ. 3: 64–65.

Labus, B., H. Schuster, W. Nobel &A. Kohler. 1977. Wirkung von toxischen Abwasser komporenten auf submerse macrophyten. Angew. Botanik 51: 17–36.

Landolt, E. &R. Kandeler. 1987. The family of Lemnaceae: A monographic study. Vol. 2. Veroff. Geobot. Inst. ETH. Stiftung Rubel, Zurich.

Lee, C. R., T. C. Sturgis &M. C. Landin. 1981. Heavy metal uptake by marsh plants in hydroponic solution cultures. J. Plant Nutr. 3(1–4): 139–151.

Leopold, A. C. &P. E. Kriederman. 1975. Plant growth and development. Ed. 2. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Low, K. S. &C. K. Lee. 1981. Copper, zinc, nickel and chromium uptake by Kankong air (Ipomoea aquatica Forsk). Pertanika 4: 16–20.

Mangi, J., K. Schmidt, J. Pankow, L. Gaines &P. Turner. 1978. Effects of chromium on some aquatic plants. Environ. Pollut. 16: 285–291.

Merian, E. (ed.) 1991. Metals and their compounds in the environment. VCH, Weinheim, Germany, and New York.

Muntau, M. 1981. Heavy metal distribution in the aquatic system “Southern Lake Maggiore 2”: Evolution and trend analysis. Mem. Ist. Ital. Idriobiol. 38: 505–529.

Nakayama, E., H. Tokoro, T. Kuwamoto &T. Fujinaga. 1981. Dissolved state of chromium in seawater. Nature 290: 768–770.

Nriagu, J. O. &E. Nieboer (eds.). 1988. Chromium in the natural and human environments. Advances in environmental sciences and technology, 20. John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Outridge, P. M. &B. N. Noller. 1991. Accumulation of toxic trace elements by fresh water vascular plants. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 121: 1–63.

Pawlisz, A. V., R. A. Kent, U. A. Schneider &C. Jefferson. 1997. Canadian water quality guidelines for chromium. Environ. Toxicol. Water Qual. 12: 185–193.

Pillord D. A., P. M. Rochhio, K. K. Carsidy, S. M. Stewart &B. D. Vabeem. 1987. Hexavalent chromium effects on carbon assimilation inSelenastrum capricornutum. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 38: 715–721.

Qian, J. H., A. Zayed, Y. L. Zhu, M. Yu &N. Terry. 1999. Phytoaccumulation of trace elements by wetland plants, III. Uptake and accumulation of ten trace elements by twelve plant species. J. Environ. Qual. 28: 1448–1455.

Rai, D., B. S. Sass &D. A. Moore. 1987. Chromium (III) hydrolysis constants and solubility of Chromium (III) hydroxide. Inorg. Chem. 26: 345–349.

Rai, U. N., R. D. Tripathi &N. Kumar. 1992. Bioaccumulation of chromium and toxicity on growth, photosynthetic pigments, photosynthesis,in vivo nitrate reductase activity and protein content in a chlorococcalean green algaGlaucocystis nostochinearum Itzigsohn. Chemosphere 25: 1721–1732.

—,S. Sinha, R. D. Tripathi &P. Chandra. 1995a. Wastewater treatability potential of some aquatic macrophytes: Removal of heavy metals. Ecol. Eng. 5: 5–12.

—,R. D. Tripathi, S. Sinha &P. Chandra. 1995b. Chromium and cadmium bioaccumulation and toxicity inHydrilla verticillata (l.f.) Royle andChara carollina Wildenow. J. Environ. Sci. Health A30(3): 537–551.

—,S. Sinha &P. Chandra. 1996. Metal biomonitoring in water resources of Eastern Ghats, Koraput (Orissa), India by aquatic plants. Environ. Monit. Assess. 43: 125–137.

Rauser, W. E.. 1987. Early effects of phytoxic burden of cadmium cobalt, nickel and zinc in white bean. Canad. J. Bot. 56: 1744–1749.

Ray, S. &W. J. White. 1976. Selected aquatic plants as indicator species for heavy metal pollution. J. Environ. Sci. Health All: 717–725.

Rebechini, H. M. &L. Hanzely. 1974. Lead-induced ultrastructural changes in chloroplasts. Z. pflanzenphysiol. Bd. 73: S377–386.

Riedel, G. F. 1989. Interspecific and geographical variation of the chromium sensitivity of algae. Pp. 11: 537–548in G. W. Suter II & M. A. Lewis (eds.), Aquatic toxicology and environmental fate. ASTM, Philadelphia.

Roy, B. K. &S. Mukherjee. 1982. Regulation of enzyme activities in MungbeanPhaseolus aureus seedlings by chromium. Environ. Pollut. A28: 1–6.

Saleh, F. Y., T. F. Parkerton, R. V. Lewis, J. H. Huang &K. L. Dickson. 1989. Kinetics of chromium transformations in the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 86: 25–41.

Satyakala, G. &K. Jamil. 1992. Chromium induced biochemical changes inEichhornia crassipes (Mart.) Solms. andPistia stratiotes L. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 48: 921–928.

Schmidt, K., J. Pankow, L. Gains &P. Turner. 1978. Effects of chromium on some aquatic plants. Environ. Pollut. 16: 285–291.

Sculthorpe, C. D. 1967. The biology of aquatic vascular plants. Edward Arnold, London.

Sen, A. K., N. G. Mondai &S. Mondai. 1987. Studies of uptake and toxic effects of Cr (VI) onPistia stratiotes. Water Sci. Technol. 7: 119–127.

Sinha, S. 1999. Accumulation of Cu, Cd, Cr, Mn and Pb from artificially contaminated soil byBacopa monnieri. Environ. Monit. Assess. 57: 253–264.

— &P. Chandra. 1990. Removal of Cu and Cr from water byBacopa monnieri L. Water Air Soil Pollut. 5: 271–276.

—,U. N. Rai, R. D. Tripathi &P. Chandra. 1993. Chromium and manganese uptake byHydrilla verticillata (l.f.) Royle, amelioration of chromium toxicity by manganese. J. Environ. Sci. Health A28: 1545–1552.

—,R. Saxena &S. Singh. 2002. Comparative studies on accumulation of Cr from metal solution and tannery effluent under repeated metal exposure by aquatic plants: Its toxic effects. Environ. Monitor. Assess. 80: 17–31.

Smith, S., P. J. Peterson &K. H. M. Kwan. 1989. Chromium accumulation, transport and toxicity in plants. Toxicol. Environ. Chem. 24: 241–251.

Stanley, R. A. 1974. The toxicity of heavy metals and salts to Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum L.). Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2: 233–341.

Stave, R. P. 1980. Chromium uptake and its effects on the growth of duck-weeds. M.S. thesis, Louisiana State Univ., Baton Rouge.

— &R. M. Knaus. 1985. Chromium removal from water by three species of duck-weeds. Aquat. Bot. 23(3): 261–273.

Sujana,M. G. & S. B. Rao. 1997. Unsafe chromium. Science Reporter, September 1997, 28–30.

Suseela, M. R., S. Sinha, S. Singh &R. Saxena. 2002. Accumulation of chromium and scanning electron microscopic studies inScirpus lacustris L. treated with metal and tannery effluent. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 68: 540–548.

Thyagarajan,G. 1992. In pursuit of better image: Survey of the Environment. The Hindu: 143–145.

Tripathi, R. D. &P. Chandra. 1991. Chromium uptake bySpirodela polyrrhiza (L.) Schielden in relation to pH & metal chelators. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 47: 764–769.

-& S. Smith. 1996. Effect of chromium (VI) on growth, pigment content, photosynthesis, nitrate reductase activity, metabolic nitrate pool and protein content in duckweed (Spirodela polyrrhiza). P. 159 in M. Yunus (ed.), International Conference on Plants and Environmental Pollution (ICPEP96) (abstracts), Lucknow, India.

Vajpayee, P., U. N. Rai, S. Sinha, R. D. Tripathi &P. Chandra. 1995. Bioremediation of tannery effluent by aquatic macrophytes. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 55: 546–553.

—,S. C. Sharma, R. D. Tripathi, U. N. Rai &M. Yunus. 1999. Bioaccumulation of chromium and toxicity to photosynthetic pigments, nitrate reductase activity and protein content ofNelumbo nucifera Gaertn. Chemosphere 39(12): 2159–2169.

—,U. N. Rai, M. B. Au, R. D. Tripathi, V. Yadav, S. Sinha &S. N. Singh. 2001. Chromium induced physiological changes inVallisneria spiralis L. and its role in phyto-remediation of tannery effluent. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 67: 246–256.

Vazquez, M. D., Ch. Poschenrieder &J. Barcelo. 1987. Chromium VI induced structural and ultrastructural changes in bush bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), Ann. Bot. 59: 427–438.

Walsh, A. R. &J. O’Halloran. 1966a. Chromium speciation in tannery effluent, I. An assessment of techniques and the role of organic Cr (III) complexes. Water Res. 30(10): 2393–2400.

——. 1966b. Chromium speciation in tannery effluent, II. Speciation in the effluent and in a receiving estuary. Water Res. 30(10): 1343–1354.

Wells, J. R., P. B. Kaufman &J. D. Jones. 1980. Heavy metal contents in some macrophytes from Saginaw Bay (Lake Huron, USA). Aquat. Bot. 9: 185–193.

Wolverton, B. C. 1981. Water hyacinth for controlling water pollution. Pp. 47–49in C. K. Varshney (ed.), Water pollution and management reviews. South Asian Publishers, New Delhi.

-& R. C. McDonald. 1978. Water hyacinth sorption rates of lead, mercury and cadmium. NASA, ERL, Tech. Mem. TMX No. 170.

Zaranyika, M. F. &T. Ndapwadza. 1995. Uptake of Ni, Zn, Fe, Co, Cr, Pb, Cu and Cd by water hyacinth (Eichhomia crassipes) in Mukuvsi and rivers, Zimbabwe. J. Environ. Sci. Health A30(1): 157–169.

Zayed, A., S. Gowthaman &N. Terry. 1998. Phytoaccumulation of trace elements by wetland plants, I. Duckweed. J. Environ. Qual. 27: 715–721.

Zurayk, R., B. Sukkariyah &R. Baalbaki. 2001. Common hydrophytes as bioindicators of nickel, chromium and cadmium pollution, Water, Air, Soil, Pollut. 127: 373–388.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chandra, P., Kulshreshtha, K. Chromium accumulation and toxicity in aquatic vascular plants. Bot. Rev 70, 313–327 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1663/0006-8101(2004)070[0313:CAATIA]2.0.CO;2

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1663/0006-8101(2004)070[0313:CAATIA]2.0.CO;2