Abstract

According to Chinese leaders’ statements, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) was created with the main purpose of financing infrastructure in Asia. In this research we analyse to what extent the initiative responds to China’s discontent with its second-level ranking within the existing international financing architecture. We use the Hegemonic Transition Theory to study the diplomatic conflict arisen between China and the US because of the launching of the AIIB, and we complete our work exploring the relevance of EU Members’ support in the acceptance of the AIIB and China’s view of global governance.

Multilateral financing institutions; development; infrastructures; international finance

Introduction

The first news about the creation of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB, or the bank) was made public in October 2013, during a visit by China’s leader, Xi Jinping, to Jakarta, Indonesia ( An Asian infrastructure bank 2013“An Asian infrastructure bank: only connect.” 2013. The Economist , October 4. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.economist.com/analects/2013/10/04/only-connect

https://www.economist.com/analects/2013/...

). The draft initiative was launched with the general purpose of obtaining funds to build infrastructures across Asia and was open to the participation of any country, but with the peculiarity that it would be kept under the leadership and control of Chinese authorities. During the following months, several Asian countries joined the project, and 21 countries (including China) signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) in October 2014 to establish the AIIB ( 21 Asian countries sign MOU 2014“21 Asian countries sign MOU on establishing Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.” 2014. Shanghai Daily , October 24. https://www.shine.cn/archive/article/article_xinhua.aspx?id=248613

https://www.shine.cn/archive/article/art...

). The US opposed the project alleging that the bank would fail to meet international transparency, environmental and labour standards, procurement requirements and other safeguards. Washington lobbied against the initiative and, consequently, some traditional allies such as the European Union (EU) countries, Australia and South Korea did not join the AIIB at that first stage ( Why China is creating 2014“Why China is creating a new ‘World Bank’ for Asia.” 2014. The Economist , November 11. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2014/11/11/why-china-is-creating-a-new-world-bank-for-asia

https://www.economist.com/the-economist-...

).

Surprisingly, on March 12, 2015, the United Kingdom became the first EU country to support the bank, provoking a dispute with the White House ( Dyer and Parke 2015Dyer G., G. Parker. 2015. “US attacks UK’s constant accommodation with China.” Financial Times , March 15. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/31c4880a-c8d2-11e4-bc64-00144feab7de

https://www.ft.com/content/31c4880a-c8d2...

). Within days, the rest of the key European countries met the initiative consolidating the global status of the AIIB. In June 2015, a list of 50 countries signed the Articles of Agreement that set the legal framework of the bank ( Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank 2015Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank - AIIB. “Asian Infrastructure Bank. Articles of Agreement.” Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. July 2, http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raisons-ralliement-europeen-banque-chinoise-concurrente-banque-mondiale-francoise-nicolas-jean-francois-di-meglio-2045013.html, 2015.

http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raiso...

). Two main countries were notoriously absent from this agreement, the US and Japan: the former concerned by the consequences of the People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) growing power; the latter questioning the need to create a new bank and reluctant to support another step that would recognize a change in regional guidance.

From Chinese leaders’ perspective, the AIIB represents a strategic initiative to attain what the new doctrine calls the ‘Chinese Dream’: wealth, strength and a new leadership ( Xi Jinping and the Chinese dream 2013“Xi Jinping and the Chinese dream.” 2013. The Economist , May 4. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2013/05/04/xi-jinping-and-the-chinese-dream

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2013/0...

). That dream includes a stronger army, and China’s strategic military movements in the islands of the South China Sea do not help to allay US and Japan’s fears ( What China wants 2014“What China wants.” 2014. The Economist , August 21. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2014/08/21/what-china-wants

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2014/0...

).

The main objective of this article is to discuss the underlying forces driving the creation of the AIIB. To that purpose, first, we examine China’s approach to global governance and multilateralism through a brief literature research, paying particular attention to conceptual similarities and dissimilarities with the EU. Afterwards, we study China’s specific motivation to create the AIIB in a context conditioned by Western powers’ opposition to changes in the existing international financial architecture. Thirdly, we underline the relevance of EU countries’ alignment with China once the US and Japan had opposed to the AIIB, and we explore whether that decision may point to a stronger EU-China long-term partnership in the arena of international relations. We finally try to determine whether China is preparing an eventual “hegemonic transmission” to become the next world leader, following the Hegemonic Stability Theory (HST) approach ( Kindleberger 1973Kindleberger, C. P. World in Depression, 1929-1939. [Oakland]: University of California Press, 1973. ), or on the contrary, is merely seeking a more multilateral international order. This qualitative analysis relies mainly on primary sources (official documents), as well as secondary scholarly and policy-oriented works.

China’s view of global governance and multilateralism: similarities with the EU and differences with the USA

China’s significant economic rise has modified the international order established after World War II. Chinese leaders have fostered a successful process of reforms towards a ‘socialist market economy with Chinese characteristics’ ( Ding 2009Ding, X. “The Socialist Market Economy: China and the World.” Science & Society 73, no. 2 (2009): 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2009.73.2.235.

https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2009.73.2.2...

), which has permitted a sustained per capita Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth in a country with a population over 1,300 million people.

From the Western perspective, China was at first a regional emerging power, but in a few years, it has become a new global leader. The PRC has adopted strategic decisions that, coherently with ‘hegemonic transition’ theorists ( Kindleberger 1973Kindleberger, C. P. World in Depression, 1929-1939. [Oakland]: University of California Press, 1973. ; Chan 2008Chan, S. China, the US and the power-transition theory: a critique . London: Routledge, 2008. ) signal that the new rising power seeks to substitute the international order mainly led by the USA. In the words of China’s Foreign Minister, the growth of China “[…] has been accompanied by the extension of its national interests beyond its neighbourhood. This is a trend of story that is both natural and unstoppable” ( Yi 2015Yi, W. 2015. “China’s role in the global and regional order: participant, facilitator and contributor. Speech at the Fourth World Peace Forum”. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, June 27. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/t1276595.shtl

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665...

).

Several scholars have pointed out that the PRC is not satisfied with the existing international architecture because it is dominated by the USA with the support of its Western partners and Japan ( Yang 2016Yang, H. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and Status Seeking: China’s Foray into Global Economic Governance.” Chinese Political Science Review 1, no. 4 (2016): 754–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0043-x

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0043-...

). However, there is no consensus about whether China’s ascent will be peaceful or conflictive. China’s Foreign Minister declared that “China is a participant as well as a facilitator and contributor in the global and regional order”, and noted that “China will always be a participant in the international order, not challenger; a facilitator, not trouble-maker; and a contributor, not a “free rider” ( Yi 2015Yi, W. 2015. “China’s role in the global and regional order: participant, facilitator and contributor. Speech at the Fourth World Peace Forum”. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, June 27. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/t1276595.shtl

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665...

).

According to Xi Jinping, the global governance system should not be monopolized by a single country ( Full Transcript: Interview with Chinese President 2015“Full Transcript: Interview with Chinese President Xi Jinping.” 2015. The Wall Street Journal , September 22. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/full-transcript-interview-with-chinese-president-xi-jinping-1442894700

https://www.wsj.com/articles/full-transc...

). The EU shares this opinion, and the unipolar moment seems to be fading and giving way to a new international system characterized by a multilayered and culturally diversified polarity ( Geeraerts 2011Geeraerts, G. “China, the EU, and the new multipolarity.” European Review 19, no. 1 (2011): 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798710000335.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S106279871000033...

). Both, China and the EU, use the terms ‘multipolarity’ and ‘multilateralism’ in their rhetoric ( Scott 2013Scott, D. A. “Multipolarity, Multilateralism and Beyond …? EU–China Understandings of the International System.” International Relations 27, no. 1 (2013): 30–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117812463153.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0047117812463153...

), and although they use these terms with different emphasis and timing, prospects for overcoming conceptual differences on global governance now appear to stand a greater chance than ever before ( Ujvari 2017Ujvari, B., ed. EU-China Co-operation in Global Governance. Going beyond the Conceptual Gap . [Brussels]: Egmont The Royal Institute for International Relations, 2017. Egmont Paper, 92. ).

Chinese initiatives to create a new system for global governance include reforms of traditional international organizations, but they do not exclude the launching of new multilateral tools such as the AIIB ( Gu 2017Gu, B. “Chinese multilateralism in the AIIB.” Journal of International Economic Law 20, no. 1 (2017): 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgx006.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgx006...

). Multilateral development finance has entered a new stage in which China and other emerging donors are increasing their own funding, while traditional donors have downplayed their engagement ( Wihtol 2014Wihtol, R. Whither Multilateral Development Finance? . [Tokyo]: Asian Development Bank Institute, 2014. ADBI Working Paper Series, no. 491. ). China has made clear the specific characteristics of its approach to developing countries. The PRC stresses that it is itself a developing country and defines its financial support as south-south cooperation ( Wihtol 2014Wihtol, R. Whither Multilateral Development Finance? . [Tokyo]: Asian Development Bank Institute, 2014. ADBI Working Paper Series, no. 491. ). China’s Beijing Consensus established a new pragmatic set of policies to achieve equitable, peaceful high-quality growth and defense of national borders and interests in developing countries ( Ramo 2004Ramo, J. C. “The Beijing Consensus”. London: The Foreign Policy Centre, 2004. ). This new set of rules differs from the Washington Consensus (fiscal austerity, privatization, and market liberalization), a scheme that was highly contested after the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) intervention in the global and Asian financial crisis ( Schüller and Wogart 2017Schüller, M., and J. P. Wogart. “The emergence of post-crisis regional financial institutions in Asia – with a little help from Europe”. Asia Europe Journal 15, no. 4 (2017): 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-017-0491-4

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-017-0491-...

).

The multilateral architecture is currently facing new challenges, while there is an intense debate on whether China will integrate and share responsibility in leading the world’s governance institutions ( Zoellick 2005Zoellick, R. B. Whither China: From Membership to Responsibility? New York, N.Y.: US Department of State, 2005. ; Ikenberry and Lim 2017Ikenberry, G. J., and D. Lim. “China’s emerging institutional statecraft: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the prospects for counter-hegemony.” Brookings , April 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/research/chinas-emerging-institutional-statecraft/

https://www.brookings.edu/research/china...

). Today’s international order is complex and multi-layered so that states can support some areas of the existing order, while opposing and working around other areas ( Ikenberry and Lim 2017Ikenberry, G. J., and D. Lim. “China’s emerging institutional statecraft: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the prospects for counter-hegemony.” Brookings , April 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/research/chinas-emerging-institutional-statecraft/

https://www.brookings.edu/research/china...

). A fast-growing China committed to socialism with Chinese characteristics “is becoming an important factor for world development” ( Yi 2015Yi, W. 2015. “China’s role in the global and regional order: participant, facilitator and contributor. Speech at the Fourth World Peace Forum”. Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, June 27. http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/t1276595.shtl

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665...

). Chinese leaders defend that it is necessary to collaborate for the reform and improvement of the international order to make it more fair and equitable, but US governments have mostly treated the PRC as a threat to the existing structure. US strategy is coherent with the HST ( Kindleberger 1973Kindleberger, C. P. World in Depression, 1929-1939. [Oakland]: University of California Press, 1973. ), which views that the only stable future multinational order ought to be led by a unique power: either USA or China.

On the contrary, most EU countries do not view China’s emergence as a challenge for either the regional or the global order, and consequently they do not share Washington’s concerns. Moreover, there are several important common features in Europe’s and China’s approaches towards security in the Asia-Pacific ( Simón and Klose 2016Simón, L., and S. Klose. “European perspectives towards the rise of Asia: contextualising the debate.” Asia Europe Journal 14, no. 3 (2016): 239–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-015-0440-z.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-015-0440-...

). Of course, China and the EU diverge on some important points. EU’s conditional policy towards China is based on the assumption that China can be persuaded to incorporate Europe’s values, but Beijing has chosen to define its own path ( Geeraerts 2011Geeraerts, G. “China, the EU, and the new multipolarity.” European Review 19, no. 1 (2011): 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798710000335.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S106279871000033...

).

China’s motivation to create the AIIB

Forces that have led Chinese authorities to launch the AIIB are twofold: first, those related to the financing and the construction of new infrastructure in Asia; and, second, the reduced role played by China in the management of Bretton Woods institutions in contrast with US influence.

Lack of modern regional infrastructures in Asia

The AIIB’s preference for infrastructure construction is in line with China’s foreign aid and investment policy. The lack of modern roads, motorways, railroads, maritime ports, etc. represents a key barrier hindering the economic growth of South-East Asia ( Asian Development Bank et al. 2005Asian Development Bank, Japan Bank for International Cooperation, World Bank. Connecting East Asia: A New Framework for Infrastructure . [Tokyo]: Tokyo Launch, 2005. ), which is evidenced by the low score obtained by most developing Asian economies in the chapter on infrastructures of the Global Competitiveness Report ( Table 1 ). Accordingly, it was estimated that developing countries required financing of US$776 billion per year for infrastructure during 2010–2020 ( Bhattacharyay 2010Bhattacharyay, B. N. Estimating Demand for Infrastructure in Energy, Transport, Telecommunications, Water and Sanitation in Asia and the Pacific: 2010–2020. ADB Institute Working Paper 248 . Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute, 2010. ).

In contrast, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the World Bank (WB) only channel about $20 billion annually to the South-East region ( Hou 2015Hou, Z. 2015. “New China-led development bank gains support, despite US pressure.” Overseas Development Institute , March 26, 2015, http://www.odi.org/

http://www.odi.org/...

), of which only half is devoted to infrastructures. As a result, several regional key projects have not been completed because of the shortage of funds (e.g., the Asian Highway Route Map and the Trans-Asian Railway). Moreover, since Chinese manufacturing activity depends on the availability of huge foreign supplies of raw materials and energy, a renewed land access to Central Asia through land infrastructures (motorways, railways) would ease those flows’ circulation ( Etzioni 2016Etzioni, A. “The Asian infrastructure investment bank: a case study of multifaceted containment.” Asian Perspective 40, no.2 (2016): 173–196. ).

The AIIB was launched with an initial paid and authorised capital of $20 billion and $100 billion respectively ( AIIB 2015Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank - AIIB. “Asian Infrastructure Bank. Articles of Agreement.” Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. July 2, http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raisons-ralliement-europeen-banque-chinoise-concurrente-banque-mondiale-francoise-nicolas-jean-francois-di-meglio-2045013.html, 2015.

http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raiso...

). Although funds only cover a small proportion of quantified needs, they represent an important step forward because they will be entirely devoted to the building of new infrastructures. It is certain that, comparatively, other multilateral institutions have a higher volume of capital (ABD: $162.8 billion; WB: $223 billion; IMF: $1,000 billion), but they are aimed at more diversified objectives.

EU member states’ participation at the ADB encouraged a stronger emphasis on human rights (loans for social issues including education and health) at the detriment of economic infrastructure projects. That shift was not welcomed by the biggest recipients, China and India, because of the aforementioned extensive need for physical infrastructure-oriented loans ( Ujvari 2016Ujvari, B., ed. The European Union and the China-led transformation of global economic governance . Brussels: Academia Press, 2016. Egmont Paper, 85. ), so that the founding of the AIIB generated an immediate “competitive reaction” from the ADB, which announced $110 billion for “high-quality” infrastructure in Asia ( Kameda 2015Kameda, M. [2015]. “Abe announces $110 billion in aid for ‘high-quality’ infrastructure in Asia.” The Japan Times , May 22. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/05/22/business/abe-announces-110-billion-in-aid-for-high-quality-infrastructure-in-asia/

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/0...

).

In short, the obvious lack of financing was a very good reason to set up the AIIB. The AIIB is an important vehicle to finance infrastructures that will enhance the integration of markets within Asia and to Europe, and the first wave of projects has evidenced that the construction of infrastructure is one of the major targets of the bank ( Gabusi 2017Gabusi, G. “Crossing the river by feeling the gold: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Financial Support to the Belt and Road Initiative”. China & World Economy 25, no. 5 (2017): 23–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12212.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12212...

). Consistently with the principles guiding China’s foreign aid programs, which include mutual benefit and non-intervention, Chinese leaders have expressed that the AIIB will not impose conditions on its investment ( Peng and Keat Tok 2016Peng, Z., T. S. K. Tok. “The AIIB and China’s Normative Power in International Financial Governance Structure.” Chinese Political Science Review 1, no. 4 (2016): 736–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-y.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-...

). Furthermore, the multilateral nature of the bank will make it easier to overcome potential political bilateral tensions in countries where China’s single presence could have been more conflictive ( Callaghan and Hubbard 2016Callaghan, M., P. Hubbard. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Multilateralism on the Silk Road.” China Economic Journal 9, no. 2 (2016): 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.1162970.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.11...

).

Insufficient recognition in traditional international financial institutions

The creation of the AIIB is also a reaction to China’s ‘second-class status’ in traditional international financial institutions. The PRC expects to become a leading actor corresponding to its economic muscle, and authors such as Rogoff support this objective ( Rogoff 2015Rogoff, K. 2015. “Will China’s Infrastructure Bank Work?.” The Guardian , Project Syndicate. April 6. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/apr/07/will-chinas-infrastructure-bank-work

https://www.theguardian.com/business/201...

), but the USA and to some extent Japan have tried to prevent a rebalancing of power within the global financial architecture ( Schüller and Wogart 2017Schüller, M., and J. P. Wogart. “The emergence of post-crisis regional financial institutions in Asia – with a little help from Europe”. Asia Europe Journal 15, no. 4 (2017): 483–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-017-0491-4

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-017-0491-...

).

In the context of the Monterrey Consensus Financing for Development ( United Nations 2003United Nations. Monterrey Consensus on financing for development . Monterrey: UN, 2003. ), an enhancement of developing countries’ participation was encouraged in the decision making within the IMF and WB. Since the decisive factor is shareholding (‘quota votes’), reform in governing bodies of the WB required a general capital increase (GCI), but at that moment there was not enough shareholder support to approve a GCI ( World Bank 2003World Bank. Enhancing Voice and Participation of Developing and Transition Countries: Progress Report . Washington, D.C.: WB, 2003. ). Finally, for the 2010 voice reform, a quota framework was developed exclusively for the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) shareholding. Nevertheless, the whole reform process eventually “resulted in a modest overall shift of voting power from developed to developing and transition countries” ( Verstergaard 2011Verstergaard, J. The World Bank and the emerging world order: adjusting to multipolarity at the second decimal point . Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies, 2011. ) ( Table 2 ).

Participation in multilateral financial institutions represents a way to exercise “soft power”; even though multilateral development banks (MDBs) are created with the rationale of reducing the level of conditionality in comparison with bilateral aid agencies and private funding ( Rodrik 1995Rodrik, D. Why is there multilateral lending?. London: Centre for Economic Policy Research, 1995. Discussion paper series. ), there is usually some correlation among shareholders’ interests and the destination of funds ( Easterly and Pfutze 2008Easterly, W., T. Pfutze. “Where does the money go? Best and worst practices in foreign aid.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22, no. 2 (2008): 29–52. ).

Today the United States plays a dominant role in the WB’s lending ( Andersen et al. 2006Andersen, T. B., H. Hansen, and T. Markussen. “US politics and World Bank IDA-Lending.” Journal of Development Studies 42, no. 5 (2006): 772–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380600741946.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0022038060074194...

; Harrigan et al. 2006Harrigan, J., C. Wang, and H. E-Said. “The economic and political determinants of IMF and World Bank lending in the Middle East and North Africa”. World Development 34, no. 2 (2006): 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.016.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005....

): funds are thought to be allocated considering, among others, trade flows ( Fleck and Kilby 2006Fleck, R. K., C. Kilby. “World Bank independence: A model and statistical analysis of U.S. influence.” Review of Development Economics 10, no. 2 (2006): 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006.00314.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006...

), or even UN voting ( Andersen et al. 2006Andersen, T. B., H. Hansen, and T. Markussen. “US politics and World Bank IDA-Lending.” Journal of Development Studies 42, no. 5 (2006): 772–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380600741946.

https://doi.org/10.1080/0022038060074194...

), given that “no other country has been as adept at exploiting its power and leverage for strategic gain” ( Rogoff 2015Rogoff, K. 2015. “Will China’s Infrastructure Bank Work?.” The Guardian , Project Syndicate. April 6. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/apr/07/will-chinas-infrastructure-bank-work

https://www.theguardian.com/business/201...

).

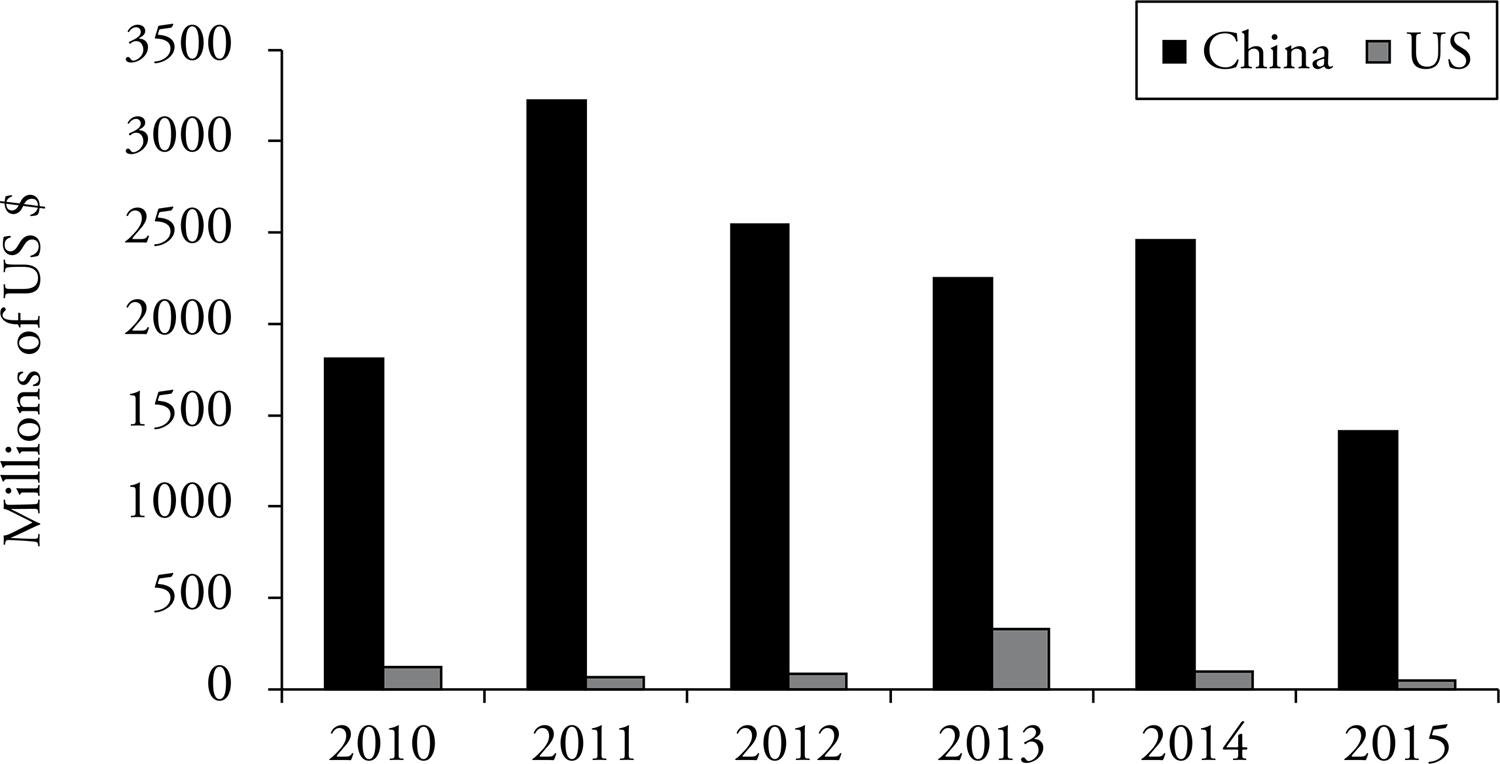

The US Congress Research Services’ periodical reports ( Nelson and Weiss 2014Nelson, R. M., and M. A. Weiss. Multilateral Development Banks: How the United States Makes and Implements Policy . Washington, D.C.: Congress Research Service Report, 2014. ; Nelson 2015Nelson, R. M. Multilateral Development Banks: US Contributions FY2000-FY-2015 . Washington, D.C.: Congress Research Service Report, 2015. ) do not hide the relevance of “U.S. Commercial Interests in MDBs […]: billions of dollars of contracts are awarded to private firms each year” ( Nelson 2013Nelson, R. M. Multilateral Development Banks: Overview and Issues for Congress . Congress Research Service Report Washington, D.C.: Congress Research Service Report, 2013. ). Moreover, in a context in which companies from China, Brazil, and India have become the main suppliers of procurement at the WB, “strategic efforts” are demanded to increase the share of contracts won by US firms ( Weiss 2012Weiss, M. A. “Multilateral Development Banks: General Capital Increases,” Congress Research Service Report . Washington, D.C.: Congress Research Service Report, 2012. ) ( Figure 1 ).

Likewise, with regard to the ADB, critics have argued that Japan and the US have often influenced lending and policy decisions: “ADB has generated substantial resources, but its policies have closely followed the preferences of its major donor, Japan” ( Krasner 1981Krasner, S. D. “Power structures and regional development banks.” International Organization 35, no. 2 (1981): 303–328. ). Some authors even suggest a greater influence of donor interests in the management of the ADB than in the WB ( Fleck and Kilby 2006Fleck, R. K., C. Kilby. “World Bank independence: A model and statistical analysis of U.S. influence.” Review of Development Economics 10, no. 2 (2006): 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006.00314.x.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006...

; Kilby 2006Kilby, C. “Donor influence in multilateral development banks: The case of Asian Development Bank”. The Review of International Organizations 1, no. 2 (2006): 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-006-8343-9.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-006-8343-...

). Increasing the influence of the PRC in the WB and the IMF would represent a new step towards a “multipolar international order” ( Geeraerts 2011Geeraerts, G. “China, the EU, and the new multipolarity.” European Review 19, no. 1 (2011): 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798710000335.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S106279871000033...

) or a “multilateralised multipolarity” ( Grevi and Vasconcelos 2008Grevi, G., and A. Vasconcelos, eds. Partnerships for effective multilateralism: EU relations with Brazil, China, Russia and India . [Paris]: Institute for Security Studies, 2008. Chaillot Paper no. 109. ). China has criticized the USA veto power in the IMF and has suggested that IMF management should have more representatives from developing countries ( Peng and Tok 2016Peng, Z., T. S. K. Tok. “The AIIB and China’s Normative Power in International Financial Governance Structure.” Chinese Political Science Review 1, no. 4 (2016): 736–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-y.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-...

). If the US transferred part of its power, it would reinforce China as a trustworthy partner, but up to present Washington has preferred to keep the status quo. The establishment of new international financial institutions reflects China’s frustration with the slow pace of reform of the WB and the IMF ( Wihtol 2015Wihtol, R. “Beijing’s Challenge to the Global Financial Architecture”. Georgetown Journal of Asian Affairs no. 15 (Spring/Summer 2015): 7–15. ). In Chinese rhetoric, the aim is to establish a fair governance structure in multilateral organizations ( Peng and Tok 2016)Peng, Z., T. S. K. Tok. “The AIIB and China’s Normative Power in International Financial Governance Structure.” Chinese Political Science Review 1, no. 4 (2016): 736–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-y.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-...

. According to the US view, reform would be a step towards hegemonic transition.

Building a new international financial architecture

Multilateral development finance went through several stages: the creation of the WB and the IMF in 1944, the establishment of regional and development banks in the 1950s and the 1960s, and the emergence of subregional banks and specialized vertical banks. In this new stage Western countries are unwilling to recapitalize and expand MDB’s operations, but they have also resisted proposals of new institutions ( Wihtol 2014Wihtol, R. Whither Multilateral Development Finance? . [Tokyo]: Asian Development Bank Institute, 2014. ADBI Working Paper Series, no. 491. ).

Asian, Inter-American and African Development Banks were created “[…] because Third World states were dissatisfied with the existing major public international financial institutions, the WB and the IMF. Developing countries believed that they would have more leverage over regional institutions” ( Krasner 1981Krasner, S. D. “Power structures and regional development banks.” International Organization 35, no. 2 (1981): 303–328. ). The challenges faced by the new international financial institutions are not new: initially, the Inter-American bank was rejected by US administration, and France and Great Britain, the two main former colonial powers in the region ( Wihtol 2015Wihtol, R. “Beijing’s Challenge to the Global Financial Architecture”. Georgetown Journal of Asian Affairs no. 15 (Spring/Summer 2015): 7–15. ), did not support the African Development Bank. As White puts it, “[…] the creation of a regional bank is essentially an act of political resistance against the developed countries’ hegemony in the world economy” ( White 1970White, J. Regional Development Banks: A study of institutional style . [London]: Overseas Development Institute, 1970. ).

The launching of the AIIB responds to the same logic. US Congress refusal to ratify 2010 voice reform has contributed to the eventual creation of new institutions. China, after having faced opposition from the US and Japan to playing a more significant role in traditional institutions, has promoted a new path. Certainly, this time the PRC’s government wants to assure the leadership, and to this purpose it has reserved 29.8% of the capital, well above the next main shareholders, namely India with 8.4% and Russia with 6.5% ( AIIB 2015Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank - AIIB. “Asian Infrastructure Bank. Articles of Agreement.” Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. July 2, http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raisons-ralliement-europeen-banque-chinoise-concurrente-banque-mondiale-francoise-nicolas-jean-francois-di-meglio-2045013.html, 2015.

http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raiso...

). Besides, the Chinese government holds 26.06% of voting shares, which gives China veto power inside AIIB.

Coherently with its critics to the IMF and the WB, the PRC has tried to propose a fairer distribution of voting rights ( Peng and Tok 2016Peng, Z., T. S. K. Tok. “The AIIB and China’s Normative Power in International Financial Governance Structure.” Chinese Political Science Review 1, no. 4 (2016): 736–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-y.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-...

). To this purpose, the distribution guarantees that Asian developing countries have larger influence than in the WB and the ADB (Asian countries have around 75% of voting rights), reserving a comparatively small proportion of shares to countries and regions outside Asia (about 25% of voting rights). Moreover, Chinese leaders are aware that AIIB success will depend on the restraint in the use of its power in the bank, so that the institution can enjoy from “performance legitimacy” in the future ( Chin 2016Chin, G. T. “Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Governance Innovation and Prospects.” Global Governance 22, no. 1 (2016): 11–25. ).

On the other hand, the AIIB is not the only institution China has promoted in order to develop a new international order. In 2014, China, together with Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa, announced the creation of the New Development Bank (BRICS-NDB) to finance reciprocal investments in infrastructure and “sustainable development” projects, with $50 billion in capital. And, in September 2013, a plan was presented to reinvigorate the ancient Silk Road with a modern network of high-speed rail, motorways, pipelines, ports and fibre-optic cables stretching across the region ( Godement and Kratz 2015Godement, F., and A. Kratz, eds. “One Belt, One Road”: China’s Great Leap Outward . [n.p.]: European Council on Foreign Relations, 2015 Jun. http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/China_analysis_belt_road.pdf

http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/China_analysis...

; The new Silk Road 2014“The new Silk Road. Stretching the threads”. 2014. The Economist , November 29. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.economist.com/china/2014/11/27/stretching-the-threads

https://www.economist.com/china/2014/11/...

; Page 2014Page, J. 2014. “China sees itself at center of new Asian order.” The Wall Street Journal , November 9. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-new-trade-routes-center-it-on-geopolitical-map-1415559290

https://www.wsj.com/articles/chinas-new-...

; Gatev 2015Gatev, I. 2015. “The Silk Road Economic Belt and Its Discontents.” China Policy Instittute: Analysis , June 23. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://cpianalysis.org/2015/06/23/the-silk-road-economic-belt-and-its-discontents/.

https://cpianalysis.org/2015/06/23/the-s...

).

In parallel, these initiatives to create a new financial architecture raise questions about Chinese attitude in the role of lender to other developing economies in South-East Asia, Africa, and Latin America. The Chinese government has announced non-interference and has tried to transmit a distinctive ‘South–South cooperation’ image. However, Chinese lending activities just seem to share what could be called a different form of conditionality ( Foster et al. 2008Foster, V., W. Butterfield, C. Chen, and N. Pushak, N. Building bridges: China’s growing role as infrastructure financier for Sub-Saharan Africa . Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, 2008. Trends and policy options, no. 5. ; Lancaster 2007Lancaster, C. 2007. “The Chinese Aid System.” Centre for Global Development, June 27. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/chinese-aid-system

https://www.cgdev.org/publication/chines...

; Mattlin and Nojonen 2011Mattlin, M., M. Nojonen. Conditionality in Chinese bilateral lending . Helsinki: Bank of Finland, 2011. Bofit discussion papers, 14. ).

Different from the traditional Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) official development assistance (ODA), the PRC finances foreign infrastructures mainly through the Ex-Im Bank, the Export-Import Bank of China, which is owned by the government and aimed at fostering trade ( Moss and Rose 2006Moss, T., and S. Rose. China Ex-Im Bank and Africa: New Lending, New Challenges . Washington: D.C.: Centre for Global Development, 2006. https://www.cgdev.org/files/11116_file_China_and_Africa.pdf. CGD Notes.

https://www.cgdev.org/files/11116_file_C...

; The Export-Import Bank of the Republic of China 2015The Export-Import Bank of the Republic of China - Ex-Im. 2014 Annual Report. Taipei City: Ex-Im Bank, 2015. ). Terms and conditions are agreed on a bilateral basis, but the China Ex-Im Bank could be increasingly using a deal structure known as the “Angola mode” or “resources for infrastructure”, whereby “repayment of the loan for infrastructure development is made in terms of natural resources” ( Foster et al. 2008Foster, V., W. Butterfield, C. Chen, and N. Pushak, N. Building bridges: China’s growing role as infrastructure financier for Sub-Saharan Africa . Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, 2008. Trends and policy options, no. 5. ). Recently adopted AIIB schemes indicates that China promotes that financial resources from MDB must be lent under concessionary conditions, theoretically following OECD ODA recommendations ( AIIB 2016Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank - AIIB. “Operational Policy on Financing.” [n. p.]: 2016 Jan [updated Mar 21, 2017], https://www.aiib.org/en/policies-strategies/_download/operation-policy/policy_operational_financing_new.pdf.

https://www.aiib.org/en/policies-strateg...

). This behaviour would as well improve the “performance legitimacy” of AIIB.

Most authors agree that China’s emergence will modify or even challenge the international financial architecture. However, there is little consensus about whether this change means the creation of an alternative architecture or just to a reform that will lead to a new multilateral architecture. Until recently, China was perceived as a ‘reformer’ of the multilateral system, but after the creation of the AIIB and other initiatives such as the BRICS-NDB, China increasingly appears as a ‘soft revisionist’ ( Renard 2015Renard, T. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB): China’s new multilateralism and the erosion of the West.” Security Policy Brief no. 65 (2015): 1–7. ).

China has contributed to the framework for investment financing, but some authors question whether these institutions compete with or complement the existing framework ( Drysdale et al. 2017Drysdale, P., A. Triggs, and J. Wang. “China’s new role in the international financial architecture.” Asian Economic Policy Review 12, no. 2 (2017): 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12182.

https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12182...

). Some media reported that the AIIB and the rest of initiatives have been launched to counterbalance or even “to rival” to the WB, the ADB and the IMF ( Sudakov 2015Sudakov, D. 2015. “New BRICS bank to change world’s financial system”. Pravda , June 24. Accessed May 19, 2018. http://www.pravdareport.com/business/finance/12-03-2015/130027-brics_bank-0/

http://www.pravdareport.com/business/fin...

; The BRICS bank: An acronym with capital 2014The BRICS bank: An acronym with capital “The BRICS bank: An acronym with capital.” 2014. The Economist , July 15. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2014/07/19/an-acronym-with-capital

https://www.economist.com/finance-and-ec...

). Instead, some scholars pointed out that it was the US, not China, that turned the AIIB into a battle for global influence ( Callaghan and Hubbard 2016Callaghan, M., P. Hubbard. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Multilateralism on the Silk Road.” China Economic Journal 9, no. 2 (2016): 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.1162970.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.11...

), because the US ‘over-reacted’ to the AIIB proposal ( Dollar 2015Dollar, D. “China’s rise as a regional and global power: The AIIB and the ‘one belt, one road’.” Horizon Papers no. 4, (Summer 2015): 162–172. ).

Some academics doubt whether the PRC is creating an alternative or complementary institutional order ( Beeson and Li 2016Beeson, M., F. Li. “China’s place in regional and global governance: A new world comes into view.” Global Policy 7, no. 4. (2016): 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12348.

https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12348...

), but most of them defend that the PRC can work well with the established economic powers in reforming the existing architecture ( Drysdale et al. 2017Drysdale, P., A. Triggs, and J. Wang. “China’s new role in the international financial architecture.” Asian Economic Policy Review 12, no. 2 (2017): 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12182.

https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12182...

). Some authors underline that the AIIB has followed international practices and was in favour of multilateralism in the setup of the AIIB, particularly after the unexpected decisions of several Western countries to participate in the initiative ( Yang 2016Yang, H. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and Status Seeking: China’s Foray into Global Economic Governance.” Chinese Political Science Review 1, no. 4 (2016): 754–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0043-x

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0043-...

). And some others underline that most of the loans approved by the AIIB have been co-financed by other MDBs (the WB, the ADB, etc.), which shows that, “these projects were not dominated by China’s narrow interest only, and were based on international credit standards” ( Gabusi 2017Gabusi, G. “Crossing the river by feeling the gold: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Financial Support to the Belt and Road Initiative”. China & World Economy 25, no. 5 (2017): 23–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12212.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12212...

).

To conclude, it is evident that the AIIB was launched to strengthen China’s soft power and to promote Chinese commercial and geopolitical interests. Through this initiative the PRC has tried to evidence some failures of the existing multilateral financing architecture, particularly the under-representation of emerging and small countries at Bretton Woods Institutions. For some, that objective could be enough to consider the initiative a challenge, but the principles and the activity of the bank do not suggest that challenging the global financial regime created by the West is PRC’s main objective. On the contrary, the AIIB rather seems to be a complement to the current system of MDB already in place

The European stance at AIIB discussions

Although China’s initial efforts at encouraging countries to join the AIIB focused on its Asian neighbours ( Huang and Chen 2015Huang, M., and N. Chen. “An analysis on the operation environment and competitiveness of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.” Asia-Pacific Development Journal 23, no. 2 (2015): 19–34. ), China has engaged European G7 members since the middle of 2014, and in early 2015 China offered to lower its own share in the bank to encourage the United States and European countries to join ( Callaghan and Hubbard 2016Callaghan, M., P. Hubbard. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Multilateralism on the Silk Road.” China Economic Journal 9, no. 2 (2016): 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.1162970.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.11...

). The invitation was not welcomed by the US and Japan; on the contrary, these countries firmly opposed the project and lobbied against the initiative.

Surprisingly, despite subsequent US pressure on its traditional European allies, during March 2015 the four largest EU economies, the United Kingdom (UK), Germany, France and Italy, decided to join the AIIB. Persuading a group of major EU countries to join the AIIB was a significant achievement to reinforce the international credibility of the bank. Apparently, a proposal forgoing veto power could have helped in attracting EU countries ( Wei and Davis 2015Wei, L., B. Davis. 2015. “China forgoes veto power at new bank to win key European nations’ support.” The Wall Street Journal , March 23. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-forgoes-veto-power-at-new-bank-to-win-key-european-nations-support-1427131055

https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-forgo...

), even if economic motivation and China’s foreign reserves were the decisive factor.

Prevalence of EU members’ individual interests

The European Commission complained that EU member states signed up for the AIIB without coordinating their decisions and ensuring representation for European institutions ( European Political Strategy Centre 2015European Political Strategy Centre - EPSC. 2015. “The Asian infrastructure investment bank: a new multilateral financial institution or a vehicle for China’s Geostrategic Goals.” European Political Strategy Center Strategic Notes no. 1, April 24. ). There was neither a joint strategy towards AIIB among EU member countries nor a clear position held by EU common institutions. The idea of “effective multilateralism” (“the practice of coordination national policies in groups of three or more states” ( Keohane 1990Keohane, R. O. “Multilateralism: an agenda for research.” International Journal 45, no. 4 (1990): 731–764. https://doi.org/10.2307/40202705.

https://doi.org/10.2307/40202705...

, 731)) as a rule for EU strategic behaviour was dismissed. The Commission and the European Investment Bank (EIB) hold 3% of the subscribed capital of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), and hence there could have been a EU joint intervention in this case ( EPSC 2015European Political Strategy Centre - EPSC. 2015. “The Asian infrastructure investment bank: a new multilateral financial institution or a vehicle for China’s Geostrategic Goals.” European Political Strategy Center Strategic Notes no. 1, April 24. ). Apparently, a joint EU response was briefly explored in the Economic and Financial Committee, but it was eventually rejected “largely due to the UK’s unilateral decision to join the bank” ( Ujvari 2016Ujvari, B., ed. The European Union and the China-led transformation of global economic governance . Brussels: Academia Press, 2016. Egmont Paper, 85. ). Finally, only the individual interests of member countries were taken into consideration, a fact that benefited those who needed world wide support for the new institution.

Surprisingly, the UK, the closest US ally, joined the initiative first, on 12 th of March 2015. Only a few days after the British government announced its decision, France, Germany and Italy expressed their intention to join the AIIB as founding members. Austria, Denmark, Finland, Hungary, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and Sweden also became founding members in 2014. The fact that only 14 EU Member States responded to China’s offer, in an apparent rush, evidences that there was no coordination on this important issue ( Renard 2015Renard, T. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB): China’s new multilateralism and the erosion of the West.” Security Policy Brief no. 65 (2015): 1–7. ; Callaghan and Hubbard 2016Callaghan, M., P. Hubbard. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Multilateralism on the Silk Road.” China Economic Journal 9, no. 2 (2016): 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.1162970.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.11...

).

In most cases, acquiring material advantages through membership can be regarded as the most important incentive. London’s future relevance as a global centre of finance was the key factor, since the UK’s membership will strengthen the City’s bid to manage AIIB transactions ( Domínguez 2015Domínguez, G. 2015. “Why Europe defies the US to join a China-led bank.” DW , March 18. Accessed May 19, 2018. http://www.dw.com/en/why-europe-defies-the-us-to-join-a-china-led-bank/a-18322773

http://www.dw.com/en/why-europe-defies-t...

). As admitted by London authorities, “demands of transferring savings to investment is a big opportunity” ( Shaohui 2015Shaohui T. 2015. “Joining AIIB is in Britain’s interest despite U.S. criticism: London mayor’s top adviser.” Xinhuanet , June 15. Accessed May 19, 2018. http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-03/15/c_134068500.htm

http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-03...

). Consistently with London’s strategy to attract Chinese banks, encourage offshore trade in the yuan and strengthen its position as the world’s main centre for foreign exchange trading, just a few days after the AIIB, the London Stock Exchange launched Europe’s first yuan-denominated money market fund ( Britain launches Europe’s first yuan money-market fund 2015“Britain launches Europe’s first yuan money-market fund”. 2015. Reuters , June 15. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-britain-china-funds-idUKKBN0ML1G120150325

https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-britai...

). In brief, the UK assessed that potential benefits were greater than the consequences of a possible, but unlikely, US retaliation ( Dyer and Parker 2015Dyer G., G. Parker. 2015. “US attacks UK’s constant accommodation with China.” Financial Times , March 15. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/31c4880a-c8d2-11e4-bc64-00144feab7de

https://www.ft.com/content/31c4880a-c8d2...

).

As for Germany, the Sino-German Joint Statement expressed that the AIIB “[...] could play an important role to provide funds for infrastructure in Asia. Germany intends to join the AIIB as a prospective founding member. China welcomes this intention” ( Joint Statement of the 1st China–Germany 2015Joint Statement of the 1st China–Germany High-Level Financial Dialogue. [Berlin]: Federal Ministry of Finance, March 17, 2015. ). Moreover, Germany is the EU country with the highest level of exports of goods to China (€75 billion in 2014, 46% of the EU total), and the one with the biggest trade surplus (€14.1 billion in 2014). Therefore, it will probably be the country to benefit the most from the AIIB’s procurement (power, transportation, communications, etc.). The so-called Germany–China axis ( Heiduk 2015Heiduk, F. “What is in a name? Germany’s strategic partnerships with Asia’s rising powers.” Asia Europe Journal 13, no. 2 (2015): 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0399-1.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0399-...

), represents a strong leverage in order to attract German authorities to Chinese positions.

With regard to France, apart from long-standing political ties, economic links in areas such as nuclear power and aerospace manufacturing were critical according to the French Ambassador to China ( Ruan 2015Ruan, V. 2015. “AIIB in quest for “best bank” standards, says French ambassador to China”. South China Morning Post , June 1. Accessed May 19, 2018. http://www.scmp.com/news/china/economy/article/1814690/aiib-quest-best-bank-standards-says-french-ambassador-china

http://www.scmp.com/news/china/economy/a...

). Similarly, mounting investments arriving from China helped the Italian government to adhere to the initiative ( After Pirelli, Chinese shopping 2015“After Pirelli, Chinese shopping spree in Italy to continue.” 2015. CNBC , March 23. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2015/03/23/after-pirelli-chinese-shopping-spree-in-italy-to-continue.html

https://www.cnbc.com/2015/03/23/after-pi...

). In the end, most EU countries considered that they were more likely to further their particular interests from the inside, taking account of a business opportunity given European know-how in manufacturing, green energies and financing, on the one hand, and Asian needs in these areas, on the other ( Nicolas 2015Nicolas, F. 2015. “Les raisons du ralliement européen à la banque chinoise concurrente de la Banque mondiale.” Atlantico , Mars 18. Accessed May 19, 2018. http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raisons-ralliement-europeen-banque-chinoise-concurrente-banque-mondiale-francoise-nicolas-jean-francois-di-meglio-2045013.html

http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raiso...

).

European multilateral institutions gained some momentum only once the AIIB had been established. In May 2016, the AIIB started to cooperate with the EBRD by signing a Memorandum of Understanding in which they agreed to collaborate through regular high-level dialogs. In May 2016, the AIIB also signed a framework for cooperation with the EIB, focusing on environmental challenges.

It must be acknowledged that the lack of an effective long-term EU strategy for China and the whole Asia comes as no surprise ( Bustillo and Maiza 2012Bustillo, R., and A. Maiza. “An analysis of the economic integration of China and the European Union: the role of European trade policy.” Asia Pacific Business Review 18, no. 3 (2012): 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2011.626990.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2011.62...

). Traditionally, European countries have spent too much time addressing domestic problems and striving for internal coherence ( Hooijmaaijers 2015Hooijmaaijers, B. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: another wakeup call for the EU?.” Global Affairs 1, no. 3 (2015): 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2015.1080895.

https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2015.10...

). Therefore, EU decisions depend mostly on the priorities of its key members. Yet, at the same time, EU Members share some basic values of their foreign policy upon which the EU’s Common Foreign and Security Policy has been built. EU countries, unlike the US, do not oppose the norms and the new financial structure proposed by China ( Peng and Tok 2016Peng, Z., T. S. K. Tok. “The AIIB and China’s Normative Power in International Financial Governance Structure.” Chinese Political Science Review 1, no. 4 (2016): 736–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-y.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-016-0042-...

). Moreover, both the EU as well as most EU member countries support the adjustment of international institutions to better match the current global economic reality ( EPSC 2016European Political Strategy Centre - EPSC. 2016. “Engaging China at a time of transition.” European Political Strategy Center Strategic Notes no. 16. ).

European contribution to the adoption of “best practices”

A total of 14 EU member states have already joined the AIIB and some others expect to get membership. For sure, the EU powers’ participation constitute a relevant asset to guarantee that the AIIB is to follow “best practices”, even if their level of influence is limited by their capital and voting shares. Germany with 4.5% of total capital is the EU country with the highest share, followed by France with 3.4%, the UK with 3.1%, and Italy with 2.6% ( AIIB 2015Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank - AIIB. “Asian Infrastructure Bank. Articles of Agreement.” Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. July 2, http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raisons-ralliement-europeen-banque-chinoise-concurrente-banque-mondiale-francoise-nicolas-jean-francois-di-meglio-2045013.html, 2015.

http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raiso...

).

On the whole, the EU countries sum 19.7% of AIIB’s capital (25% is reserved to non-regional members), and the quote reaches 28.2% when all European countries are taken into consideration, plus Australia, Korea, and New Zealand. That is a highly relevant participation given that several important decisions will require three-quarters of the votes, assuring non-Chinese-dependent economies will have a say in the practices of the bank. Moreover, since the fragmented EU response has been somewhat remedied by the fact that EU members have organised themselves into two constituencies or unified external representations in the AIIB ( Ujvari 2016Ujvari, B., ed. The European Union and the China-led transformation of global economic governance . Brussels: Academia Press, 2016. Egmont Paper, 85. ), it will be easier to manage potential coalitions with other partners. On the other hand, the way that the Brexit will impact EU-China and UK-China relationships remains uncertain to a great extent ( Le Corre 2016Le Corre, P. 2016. “Sino-EU relations, a post-Brexit jump into the unknown?.” Nikkei Asian Review . July 8. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Philippe-Le-Corre-Sino-EU-relations-a-post-Brexit-jump-into-the-unknown

https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Philipp...

; Suokas 2016Suokas, J. 2016. “AIIB chief says Brexit does not change UK’s major role in the bank.” GBTimes , June 25. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://gbtimes.com/aiib-chief-says-brexit-does-not-change-uks-major-role-bank

https://gbtimes.com/aiib-chief-says-brex...

; Kuo 2016Kuo, M. A. 2016. “US-UK-China Relations: Post-Brexit Outlook.” The Diplomat , June 26. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/us-uk-china-relations-post-brexit-outlook/

https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/us-uk-ch...

).

It is evident that EU countries’ support provided legitimacy to China’s initiative, isolating the US and Japan. Besides, European countries played an important role in triggering membership applications by other traditional US allies, namely Australia and South Korea, so that the AIIB has become perhaps China’s largest soft power success so far ( Renard 2015Renard, T. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB): China’s new multilateralism and the erosion of the West.” Security Policy Brief no. 65 (2015): 1–7. ). As a result, Japanese attitude towards the AIIB has become less aggressive, and USA seems to be changing its mind from non-declared opposition to expectancy, as expressed by President Obama jointly with Japanese Prime Minister Abe ( Talley 2015Talley, I. 2015. Obama: We’re all for the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank”. The Wall Street Journal , April 28. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2015/04/28/obama-were-all-for-the-asian-infrastructure-investment-bank/

https://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2015/04/...

).

Some authors have suggested that a sort of complementariness between ADB-WB and AIIB could be sought: AIIB would concentrate on large infrastructure projects whereas ADB-WB could focus on “irrigation systems and arterial and rural roads” ( Chin 2016Chin, G. T. “Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Governance Innovation and Prospects.” Global Governance 22, no. 1 (2016): 11–25. ). Indeed, the AIIB has already signed a Co-financing Framework Agreement with the World Bank, on the 13 th of April 2016, and a similar agreement with the ADB, on the 2 nd of May, 2016.

The adoption of those agreements, the recruiting of high-level staff from “non-suspicious” countries such as Japan, altogether with the participation of strong shareholders indicate that very likely the AIIB will respect international standards, reducing the risk of being utilised as an arm of Chinese foreign policy ( The Asian Infrastructure Investment 2015The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: The infrastructure gap “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: The infrastructure gap.” 2015. The Economist, March 19. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.economist.com/asia/2015/03/19/the-infrastructure-gap

https://www.economist.com/asia/2015/03/1...

). Nevertheless, “membership remains off the table in both Washington and Tokyo” ( Ujvari 2016Ujvari, B., ed. The European Union and the China-led transformation of global economic governance . Brussels: Academia Press, 2016. Egmont Paper, 85. ). Even if the Chinese Finance Minister Lou Jiwei declared that the AIIB would be the first MDB “mainly led by developing countries” ( Curran 2015Curran, E. 2015. “China’s New bank offers fresh approach to old problems.” Bloomberg , March 26. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-03-26/china-s-new-bank-offers-fresh-approach-to-old-problems

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/...

), the bank is controlled by China, which motives the US and Japan to stay alert to potential geopolitical consequences.

The establishment of the AIIB did not depend on European support. Some scholars even consider that “many European countries thought they needed the AIIB as a means of engagement with China more than China needed them to establish the bank” ( Callaghan and Hubbard 2016Callaghan, M., P. Hubbard. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Multilateralism on the Silk Road.” China Economic Journal 9, no. 2 (2016): 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.1162970.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.11...

). In any case, it is thanks to the warm response of the Europeans that the AIIB so rapidly has become a substantial part of the global financial architecture for development ( Gabusi 2017Gabusi, G. “Crossing the river by feeling the gold: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Financial Support to the Belt and Road Initiative”. China & World Economy 25, no. 5 (2017): 23–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12212.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12212...

). More importantly, European support for the AIIB can be interpreted as part of a strategy to encourage China to play a larger role in the multilateral global system ( Renard 2015Renard, T. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB): China’s new multilateralism and the erosion of the West.” Security Policy Brief no. 65 (2015): 1–7. ).

Some voices have claimed the potential benefits of a higher involvement of EU countries in the ADB in terms of economic, political, and geostrategic reasons ( Okano-Heijmans 2015Okano-Heijmans, M. “Untapped potential: time to rethink European engagement with the Asian Development Bank.” Asia Europe Journal 13, no. 2 (2015): 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0395-5.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0395-...

), but European economies have preferred a more balanced approach to the region, seeking equilibrium in relations towards Japan on the one hand, and China on the other. Perhaps, a more intense use of structures and mechanisms provided by the Asia Europe Meeting (ASEM), where both China and Japan participate, could become an important vehicle to get that badly needed long-term and holistic approach to Asia ( Reiterer 2009Reiterer, M. “Asia–Europe Meeting (ASEM): Fostering a multipolar world order through inter-regional cooperation.” Asia Europe Journal 7, no. 1 (2009): 179–196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-008-0210-2.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-008-0210-...

). Although mainly steered by individual member countries’ interest, the EU´s behaviour towards AIIB somehow reflects its willingness to permit a stronger Chinese influence in an increasingly multilateral future world financial order.

Conclusions

The creation of the AIIB represents a good chance to finance some much-needed infrastructure in the South-East Asian region. At the same time, the launching of a new multilateral bank led by Chinese authorities represents a substantial alteration of the current international order that shows the PRC’s displeasure with its second-level role at established international institutions.

China defends a new view of global governance based on “multipolarity” and “multilaterality”. The PRC is creating a whole set of financing instruments and, in this research we have evidenced that the AIIB represents a cornerstone of a new international financing architecture more coherent with the Beijing Consensus and, in Chinese rhetoric, more sensitive to developing countries’ needs.

On the contrary, the USA is more comfortable with the idea of “unipolarity” and supports the theory of one “unique hegemonic power”. Consequently, the USA altogether with Japan lobbied against the AIIB, but in the end China’s economic strength was enough to attract neighbouring countries and, more importantly, traditional US allies (the UK, France, Australia and South-Korea).

We conclude that EU Members’ support was very relevant for the rapid acceptance of the AIIB. The participation of EU economic powers, albeit limited, was taken as a guarantee of good practice. More importantly, even though EU powers reacted in an individual way, we conclude that sharing and promoting a “multipolar” order represents an important common value of EU-China partnership.

Even if reluctantly, Japan and the USA have finally agreed to co-operate with the AIIB. Consequently, Chinese AIIB creation cannot be considered as a clear step towards “hegemonic transition”, since the AIIB is going to be managed with the help and cooperation of the other MDBs. Instead, the creation of the AIIB should simply be labelled a progress towards a more multilateral financial world order.

References

- “21 Asian countries sign MOU on establishing Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.” 2014. Shanghai Daily , October 24. https://www.shine.cn/archive/article/article_xinhua.aspx?id=248613

» https://www.shine.cn/archive/article/article_xinhua.aspx?id=248613 - “After Pirelli, Chinese shopping spree in Italy to continue.” 2015. CNBC , March 23. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.cnbc.com/2015/03/23/after-pirelli-chinese-shopping-spree-in-italy-to-continue.html

» https://www.cnbc.com/2015/03/23/after-pirelli-chinese-shopping-spree-in-italy-to-continue.html - “An Asian infrastructure bank: only connect.” 2013. The Economist , October 4. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.economist.com/analects/2013/10/04/only-connect

» https://www.economist.com/analects/2013/10/04/only-connect - Andersen, T. B., H. Hansen, and T. Markussen. “US politics and World Bank IDA-Lending.” Journal of Development Studies 42, no. 5 (2006): 772–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380600741946

» https://doi.org/10.1080/00220380600741946 - Asian Development Bank, Japan Bank for International Cooperation, World Bank. Connecting East Asia: A New Framework for Infrastructure . [Tokyo]: Tokyo Launch, 2005.

- Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank - AIIB. “Operational Policy on Financing.” [n. p.]: 2016 Jan [updated Mar 21, 2017], https://www.aiib.org/en/policies-strategies/_download/operation-policy/policy_operational_financing_new.pdf

» https://www.aiib.org/en/policies-strategies/_download/operation-policy/policy_operational_financing_new.pdf - Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank - AIIB. “Asian Infrastructure Bank. Articles of Agreement.” Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. July 2, http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raisons-ralliement-europeen-banque-chinoise-concurrente-banque-mondiale-francoise-nicolas-jean-francois-di-meglio-2045013.html, 2015.

» http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raisons-ralliement-europeen-banque-chinoise-concurrente-banque-mondiale-francoise-nicolas-jean-francois-di-meglio-2045013.html - Beeson, M., F. Li. “China’s place in regional and global governance: A new world comes into view.” Global Policy 7, no. 4. (2016): 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12348

» https://doi.org/10.1111/1758-5899.12348 - Bhattacharyay, B. N. Estimating Demand for Infrastructure in Energy, Transport, Telecommunications, Water and Sanitation in Asia and the Pacific: 2010–2020. ADB Institute Working Paper 248 . Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute, 2010.

- “Britain launches Europe’s first yuan money-market fund”. 2015. Reuters , June 15. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-britain-china-funds-idUKKBN0ML1G120150325

» https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-britain-china-funds-idUKKBN0ML1G120150325 - Bustillo, R., and A. Maiza. “An analysis of the economic integration of China and the European Union: the role of European trade policy.” Asia Pacific Business Review 18, no. 3 (2012): 355–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2011.626990

» https://doi.org/10.1080/13602381.2011.626990 - Callaghan, M., P. Hubbard. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Multilateralism on the Silk Road.” China Economic Journal 9, no. 2 (2016): 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.1162970

» https://doi.org/10.1080/17538963.2016.1162970 - Chan, S. China, the US and the power-transition theory: a critique . London: Routledge, 2008.

- Chin, G. T. “Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: Governance Innovation and Prospects.” Global Governance 22, no. 1 (2016): 11–25.

- Curran, E. 2015. “China’s New bank offers fresh approach to old problems.” Bloomberg , March 26. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-03-26/china-s-new-bank-offers-fresh-approach-to-old-problems

» https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-03-26/china-s-new-bank-offers-fresh-approach-to-old-problems - Ding, X. “The Socialist Market Economy: China and the World.” Science & Society 73, no. 2 (2009): 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2009.73.2.235

» https://doi.org/10.1521/siso.2009.73.2.235 - Dollar, D. “China’s rise as a regional and global power: The AIIB and the ‘one belt, one road’.” Horizon Papers no. 4, (Summer 2015): 162–172.

- Domínguez, G. 2015. “Why Europe defies the US to join a China-led bank.” DW , March 18. Accessed May 19, 2018. http://www.dw.com/en/why-europe-defies-the-us-to-join-a-china-led-bank/a-18322773

» http://www.dw.com/en/why-europe-defies-the-us-to-join-a-china-led-bank/a-18322773 - Drysdale, P., A. Triggs, and J. Wang. “China’s new role in the international financial architecture.” Asian Economic Policy Review 12, no. 2 (2017): 258–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12182

» https://doi.org/10.1111/aepr.12182 - Dyer G., G. Parker. 2015. “US attacks UK’s constant accommodation with China.” Financial Times , March 15. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/31c4880a-c8d2-11e4-bc64-00144feab7de

» https://www.ft.com/content/31c4880a-c8d2-11e4-bc64-00144feab7de - Easterly, W., T. Pfutze. “Where does the money go? Best and worst practices in foreign aid.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 22, no. 2 (2008): 29–52.

- Etzioni, A. “The Asian infrastructure investment bank: a case study of multifaceted containment.” Asian Perspective 40, no.2 (2016): 173–196.

- European Political Strategy Centre - EPSC. 2015. “The Asian infrastructure investment bank: a new multilateral financial institution or a vehicle for China’s Geostrategic Goals.” European Political Strategy Center Strategic Notes no. 1, April 24.

- European Political Strategy Centre - EPSC. 2016. “Engaging China at a time of transition.” European Political Strategy Center Strategic Notes no. 16.

- Fleck, R. K., C. Kilby. “World Bank independence: A model and statistical analysis of U.S. influence.” Review of Development Economics 10, no. 2 (2006): 224–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006.00314.x

» https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9361.2006.00314.x - Foster, V., W. Butterfield, C. Chen, and N. Pushak, N. Building bridges: China’s growing role as infrastructure financier for Sub-Saharan Africa . Washington, D.C.: The World Bank, 2008. Trends and policy options, no. 5.

- “Full Transcript: Interview with Chinese President Xi Jinping.” 2015. The Wall Street Journal , September 22. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.wsj.com/articles/full-transcript-interview-with-chinese-president-xi-jinping-1442894700

» https://www.wsj.com/articles/full-transcript-interview-with-chinese-president-xi-jinping-1442894700 - Gabusi, G. “Crossing the river by feeling the gold: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Financial Support to the Belt and Road Initiative”. China & World Economy 25, no. 5 (2017): 23–45. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12212

» http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cwe.12212 - Gatev, I. 2015. “The Silk Road Economic Belt and Its Discontents.” China Policy Instittute: Analysis , June 23. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://cpianalysis.org/2015/06/23/the-silk-road-economic-belt-and-its-discontents/

» https://cpianalysis.org/2015/06/23/the-silk-road-economic-belt-and-its-discontents/ - Geeraerts, G. “China, the EU, and the new multipolarity.” European Review 19, no. 1 (2011): 57–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798710000335

» https://doi.org/10.1017/S1062798710000335 - Godement, F., and A. Kratz, eds. “One Belt, One Road”: China’s Great Leap Outward . [n.p.]: European Council on Foreign Relations, 2015 Jun. http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/China_analysis_belt_road.pdf

» http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/China_analysis_belt_road.pdf - Grevi, G., and A. Vasconcelos, eds. Partnerships for effective multilateralism: EU relations with Brazil, China, Russia and India . [Paris]: Institute for Security Studies, 2008. Chaillot Paper no. 109.

- Gu, B. “Chinese multilateralism in the AIIB.” Journal of International Economic Law 20, no. 1 (2017): 137–158. https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgx006

» https://doi.org/10.1093/jiel/jgx006 - Harrigan, J., C. Wang, and H. E-Said. “The economic and political determinants of IMF and World Bank lending in the Middle East and North Africa”. World Development 34, no. 2 (2006): 247–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.016

» https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2005.07.016 - Heiduk, F. “What is in a name? Germany’s strategic partnerships with Asia’s rising powers.” Asia Europe Journal 13, no. 2 (2015): 131–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0399-1

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-014-0399-1 - Hooijmaaijers, B. “The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank: another wakeup call for the EU?.” Global Affairs 1, no. 3 (2015): 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2015.1080895

» https://doi.org/10.1080/23340460.2015.1080895 - Hou, Z. 2015. “New China-led development bank gains support, despite US pressure.” Overseas Development Institute , March 26, 2015, http://www.odi.org/

» http://www.odi.org/ - Huang, M., and N. Chen. “An analysis on the operation environment and competitiveness of Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.” Asia-Pacific Development Journal 23, no. 2 (2015): 19–34.

- Ikenberry, G. J., and D. Lim. “China’s emerging institutional statecraft: the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the prospects for counter-hegemony.” Brookings , April 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/research/chinas-emerging-institutional-statecraft/

» https://www.brookings.edu/research/chinas-emerging-institutional-statecraft/ - Joint Statement of the 1st China–Germany High-Level Financial Dialogue. [Berlin]: Federal Ministry of Finance, March 17, 2015.

- Kameda, M. [2015]. “Abe announces $110 billion in aid for ‘high-quality’ infrastructure in Asia.” The Japan Times , May 22. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/05/22/business/abe-announces-110-billion-in-aid-for-high-quality-infrastructure-in-asia/

» https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/05/22/business/abe-announces-110-billion-in-aid-for-high-quality-infrastructure-in-asia/ - Keohane, R. O. “Multilateralism: an agenda for research.” International Journal 45, no. 4 (1990): 731–764. https://doi.org/10.2307/40202705

» https://doi.org/10.2307/40202705 - Kilby, C. “Donor influence in multilateral development banks: The case of Asian Development Bank”. The Review of International Organizations 1, no. 2 (2006): 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-006-8343-9

» https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-006-8343-9 - Kindleberger, C. P. World in Depression, 1929-1939. [Oakland]: University of California Press, 1973.

- Krasner, S. D. “Power structures and regional development banks.” International Organization 35, no. 2 (1981): 303–328.

- Kuo, M. A. 2016. “US-UK-China Relations: Post-Brexit Outlook.” The Diplomat , June 26. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/us-uk-china-relations-post-brexit-outlook/

» https://thediplomat.com/2016/06/us-uk-china-relations-post-brexit-outlook/ - Lancaster, C. 2007. “The Chinese Aid System.” Centre for Global Development, June 27. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/chinese-aid-system

» https://www.cgdev.org/publication/chinese-aid-system - Le Corre, P. 2016. “Sino-EU relations, a post-Brexit jump into the unknown?.” Nikkei Asian Review . July 8. Accessed May 19, 2018. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Philippe-Le-Corre-Sino-EU-relations-a-post-Brexit-jump-into-the-unknown

» https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Philippe-Le-Corre-Sino-EU-relations-a-post-Brexit-jump-into-the-unknown - Mattlin, M., M. Nojonen. Conditionality in Chinese bilateral lending . Helsinki: Bank of Finland, 2011. Bofit discussion papers, 14.

- Moss, T., and S. Rose. China Ex-Im Bank and Africa: New Lending, New Challenges . Washington: D.C.: Centre for Global Development, 2006. https://www.cgdev.org/files/11116_file_China_and_Africa.pdf CGD Notes.

» https://www.cgdev.org/files/11116_file_China_and_Africa.pdf - Nelson, R. M. Multilateral Development Banks: Overview and Issues for Congress . Congress Research Service Report Washington, D.C.: Congress Research Service Report, 2013.

- Nelson, R. M. Multilateral Development Banks: US Contributions FY2000-FY-2015 . Washington, D.C.: Congress Research Service Report, 2015.

- Nelson, R. M., and M. A. Weiss. Multilateral Development Banks: How the United States Makes and Implements Policy . Washington, D.C.: Congress Research Service Report, 2014.

- Nicolas, F. 2015. “Les raisons du ralliement européen à la banque chinoise concurrente de la Banque mondiale.” Atlantico , Mars 18. Accessed May 19, 2018. http://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/raisons-ralliement-europeen-banque-chinoise-concurrente-banque-mondiale-francoise-nicolas-jean-francois-di-meglio-2045013.html