Published online Dec 18, 2023. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v11.i7.351

Peer-review started: September 10, 2023

First decision: September 29, 2023

Revised: October 4, 2023

Accepted: October 23, 2023

Article in press: October 23, 2023

Published online: December 18, 2023

Sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS) is commonly prescribed for the management of hyperkalemia, a critical electrolyte imbalance contributing to over 800000 annual visits to emergency departments.

To conduct a systematic review of documented cases of SPS-induced colitis and assess its associated prognosis.

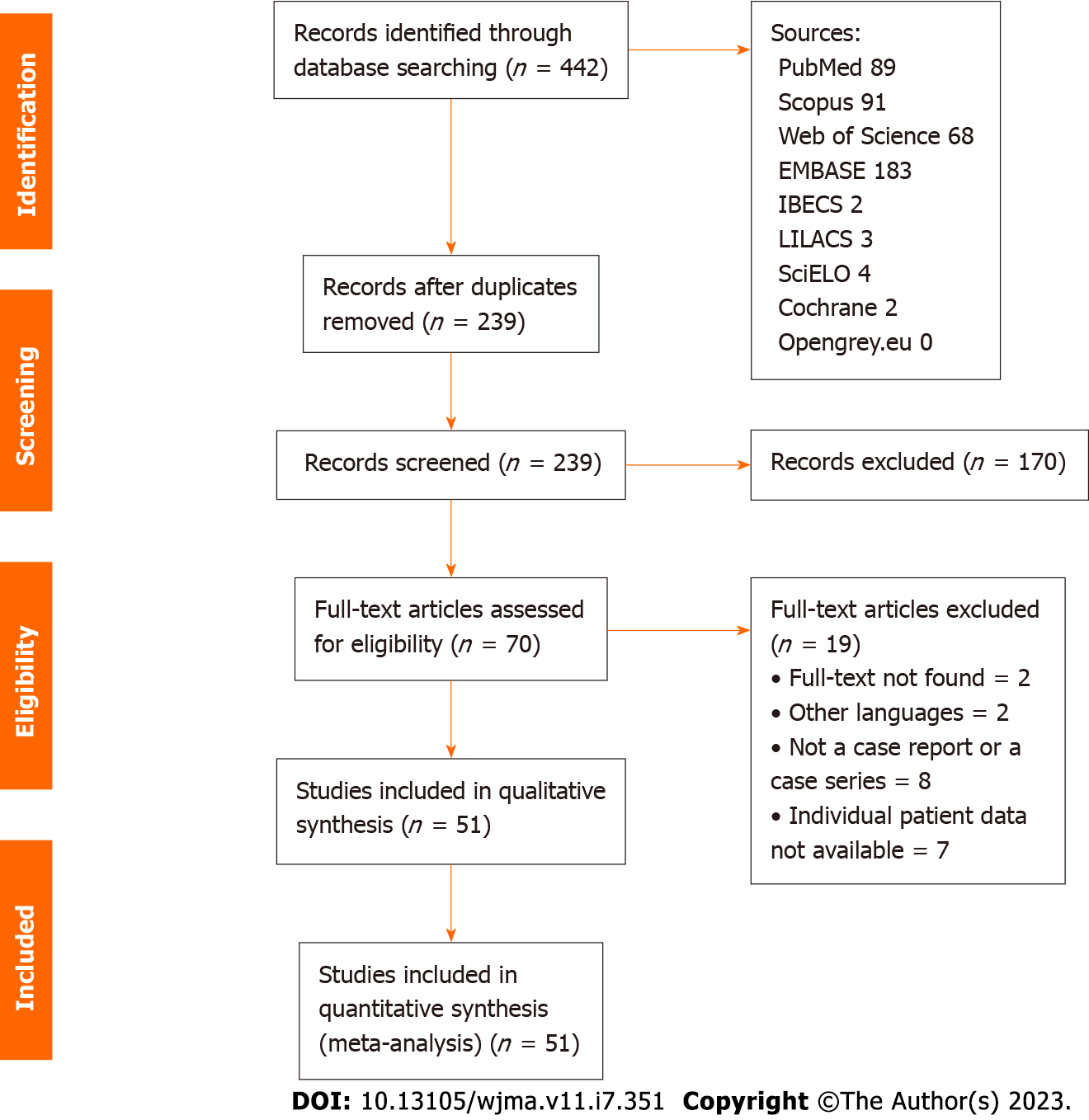

Following the PRISMA-P guidelines, our study employed Medical Subject Headings and Health Sciences Descriptors, skillfully combined using Boolean operators, to conduct comprehensive searches across various electronic databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE (PubMed), BIREME (Biblioteca Regional de Medicina), LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online), Embase, and Opengray.eu. Language criteria were confined to English, Spanish, and Portuguese, with no limitations on the publication date. Additionally, we manually scrutinized the reference lists of retrieved studies. To present our findings, we utilized simple descriptive analysis.

Our search strategy yielded a total of 442 references. After rigorous evaluation, we included 51 references, encompassing 59 documented cases of colitis. Predominant clinical presentations included abdominal pain, observed in 35 (60.3%) cases, and bloating, reported in 18 (31%) cases. The most frequently affected sites of inflammation were the cecum, rectum, and small intestine, accounting for 31%, 25.8%, and 22.4% of cases, respectively. Colonoscopy findings were described in 28 (48.2%) cases, and 29 (50%) of patients required surgical intervention. Among the subset of patients for whom outcome data was available, 39 (67.2%) experienced favorable outcomes, while 12 (20.6%) unfortunately succumbed to the condition. The mean time required for resolution was 36.7 d, with a range spanning from 1 to 120 d.

SPS demonstrates the capacity to effectively lower serum potassium levels within 24 h. However, this benefit is not without the risk of bowel injury. Our study highlights the absence of high-quality data pertaining to the incidence of adverse events associated with SPS usage, making it challenging to determine whether the potential risks outweigh the benefits. However, a significant mortality rate related to SPS-induced colitis was noted. Future investigations should prioritize randomized controlled trials with a sufficiently large patient cohort to ascertain the true utility and safety profile of this medication.

Core Tip: Our systematic review on sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS)-induced colitis underscores the critical need for a comprehensive understanding of the associated risks. While SPS effectively addresses hyperkalemia, our findings reveal a notable incidence of bowel injury. With limited high-quality data available, the balance between benefits and risks remains unclear. Future research, particularly randomized controlled trials, is essential to determine the true utility and safety profile of SPS in clinical practice.

- Citation: Aver GP, Ribeiro GF, Ballotin VR, Santos FSD, Bigarella LG, Riva F, Brambilla E, Soldera J. Comprehensive analysis of sodium polystyrene sulfonate-induced colitis: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal 2023; 11(7): 351-367

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v11/i7/351.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v11.i7.351

Adverse drug events span a broad spectrum of clinical presentations, affecting various organ systems. Recognizing and understanding these medication-related effects is essential for mitigating associated morbidity and mortality[1]. Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate (SPS) has found a specific niche in the management of hyperkalemia, a life-threatening electrolyte disturbance that leads to over 800000 emergency department visits annually[2]. This therapeutic agent gained approval from the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1958, four years prior to the implementation of the Kefauver–Harris Drug Amendments, legislation designed to ensure drug efficacy and safety[3].

The effective management of hyperkalemia is of paramount importance for preserving life, as it serves as a protective barrier against potentially fatal arrhythmias by either facilitating potassium translocation from the serum into cells or enhancing renal potassium excretion[4]. SPS, a cation exchange resin, can be administered orally or rectally, primarily exerting its effects within the colon by facilitating the exchange of sodium ions for potassium ions[1,4,5]. Nevertheless, it is crucial to note that this drug is not without its share of side effects[6]. Historically, it has been co-administered with sorbitol, an osmotic laxative, to mitigate the risk of severe constipation or fecal impaction, which can occur when SPS is administered in isolation[1]. The FDA, in 2009, issued a black box warning to underscore the heightened risk of intestinal necrosis associated with this combination therapy[3].

Typically, gastrointestinal adverse effects manifest as mild symptoms, such as nausea and constipation[7]. However, more severe and potentially fatal complications, including colonic ulceration, severe colitis, and necrosis, have been linked to SPS therapy[7,8]. Notably, the severity of these complications tends to correlate with the overall clinical condition of patients, particularly those with a history of organ transplantation, chronic kidney failure, or individuals in the postoperative period[4].

One of the most widely accepted theories regarding the mechanism of injury revolves around the presence of renin in high concentrations among patients with renal failure. The activation of renin and subsequent splanchnic vasoconstriction may lead to non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia, predisposing the colonic mucosa to injuries and electrolyte disturbances. However, it remains unclear why patients with renal failure are more susceptible to this catastrophic complication. It is possible that they are more prone to hyperkalemia, necessitating higher doses of SPS treatment than other patient groups[4].

Typically, the colon represents the gastrointestinal tract most frequently affected by SPS-induced complications. These lesions necessitate endoscopic or colonoscopic analysis with biopsy to rule out differential pathologies such as cancer. While gastric involvement is less common, it was identified in only two cases in our comprehensive review. Biopsy results typically reveal intestinal necrosis, ulcers, or perforations, with more than 90% of tissue samples exhibiting an accumulation of SPS crystals. The presence of kayexalate crystals in pathology specimens distinguishes kayexalate-induced necrosis from ischemic necrosis. Histological evidence of angulated crystals of sodium polystyrene sulfate in areas of mucosal erosions, ulcerations, or frank necrosis strongly suggests the diagnosis. Additional related findings include inflammatory exudates, pseudomembrane formation, and acute/chronic serositis. These crystals are typically identified adhered to the mucosa or embedded within the inflammatory milieu and ulcerations. Thus, in reaching a diagnosis, it is imperative to rule out conditions that can mimic SPS-induced effects, such as neoplasms, inflammatory diseases, and infectious diseases[4].

The objective is to conduct a systematic review of documented cases of SPS-induced colitis and to assess the overall prognosis associated with this condition.

This study was carried out under the recommendations contained in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines[9]. Our systematic review protocol was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), maintained by York University (CRD42022265756).

Studies were retrieved using the terms described in Supplementary material. Searches were run in January 2021 on the electronic databases Scopus, Web of Science, MEDLINE (PubMed), BIREME (Biblioteca Regional de Medicina), LILACS (Latin American and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature), SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online), Embase and Opengray.eu. There was no date of publication restrictions. The reference lists of the retrieved studies were submitted to manual search. Authors were contacted when full text was not found.

Case report or case series studies were eligible for selection. If there was more than one study published using the same case, the most recent study was selected for analysis. Studies published only as abstracts were included, as long as the data available made data collection possible. Studies written in languages other than English, Spanish, French or Portuguese were excluded.

An initial screening of titles and abstracts was the first stage to select potentially relevant papers. The second step was the analysis of the full-length papers. Two independent reviewers (GPA and GFR) extracted data using a standardized form after assessing and reaching consensus on eligible studies. The same reviewers separately assessed each study and extracted data about the characteristics of the subjects and the outcomes measured. A third reviewer (LGB) was responsible for clearing divergences in study selection and data extraction.

Methodological quality assessment of case reports and case series was performed by two independent authors (GPA and GFR) using the tool presented by Murad et al[10]. Divergences were discussed with a third reviewer (LGB) until consensus was reached. Since questions 5 and 6 of the original tool are mostly relevant to cases of adverse drug events, we modified them to better suit the cases of polystyrene-induced colitis. Therefore, we considered question 5 as ‘was there gastrointestinal damage in the case of reexposure?' and question 6 as ‘was there a temporal relationship between exposure and outcome?'.

Simple descriptive statistics, such as the mean and standard deviation (SD), frequency, and median were used to characterize the data. Data were summarized using RStudio (version 4.0.2).

A systematic search yielded a total of 442 references, from which 203 duplicates were excluded. Subsequently, a meticulous evaluation of titles and abstracts led to the exclusion of 169 references. A total of 69 full-text papers underwent thorough analysis. In the final phase, 51 references, encompassing a total of 59 cases, were included in the study. The search process is visually depicted in Figure 1. The inclusion criteria for studies were either case reports or case series.

The distribution of cases across different regions revealed that the United States of America (USA), India, Canada, and Thailand accounted for the majority, with proportions of 48.2%, 10.3%, 6.9%, and 5.1%, respectively. Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics of the included cases. Among the 59 patients, 34 (58.6%) were male. The age spectrum encompassed individuals from less than 1 year old to 89 years old, with a mean age of 60.6 years. All patients received a diagnosis of SPS-induced colitis. The predominant type of polystyrene was sodium (Kayexalte) in 47 (81%) patients, while calcium (Kalimate) polystyrene was administered to 11 patients, with a mean dose of 83.6 g administered orally in the 38 cases where the dose was reported. It is noteworthy that all cases included in the analysis were derived from publications in medical journals.

| Variable | Patients, n = 59 (100%) |

| Mean age (yr) (SD) | 60.6 ± 16.6 |

| Sex (male) | 35 (60.3) |

| Signals and symptoms | |

| Abdominal pain | 35 (60.3) |

| Bloating | 18 (31) |

| Hematochezia | 18 (31) |

| Constipation | 7 (12) |

| Diarrhea | 7 (12) |

| Hypotension | 6 (10.3) |

| Melena | 4 (6.9) |

| Fatigue | 4 (6.9) |

| Fever | 4 (6.9) |

| Vomiting | 4 (6.9) |

| Pneumoperitoneum | 3 (5.1) |

| Gastrointestinal involvement | |

| Cecum | 18 (31) |

| Rectum | 15 (25.8) |

| Small intestine | 13 (22.4) |

| Transverse colon | 10 (17.2) |

| Ascendent colon | 9 (15.5) |

| Sigmoid | 9 (15.5) |

| Descendent colon | 8 (13.7) |

| Pancolitis | 3 (5.1) |

| Stomach | 2 (3.4) |

| Mean potassium levels (mmol/L) (SD) | 6.5 ± 0.98 |

| Comorbidities | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 37 (63.7) |

| Hypertension | 20 (34.4) |

| Type 2 diabetes | 12 (20.6) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 7 (12) |

| Coronary artery disease | 6 (10.3) |

| Polystyrene type | |

| Calcium (Kalimate) | 11 (18.9) |

| Sodium (Kayexalte) | 47 (81) |

| Mean polystyrene dose (g) (SD) | 83.6 ± 70 |

| Administration route | |

| Per os | 38 (65.5) |

| Retal | 5 (8.6) |

| Per os and retal | 3 (5.1) |

| Mean time of onset symptoms (d) (SD) | 5.5 ± 6.9 |

| Biopsy | 51 (87.9) |

| Treatment | |

| Surgery | 29 (50) |

| Outcomes | |

| Recovery | 39 (67.2) |

| Death | 12 (20.6) |

| Mean time to outcome (d) (SD) | 36.7 ± 35.5 |

Abdominal pain and bloating were the most prevalent clinical presentations, observed in 35 (60.3%) and 18 (31%) cases, respectively. Hematochezia, constipation, and diarrhea followed, with frequencies of 29.3%, 12%, and 12%, respectively. A smaller proportion, 6 (10.3%) patients, presented with hypotension. Less frequent manifestations included melena, fatigue, fever, and vomiting, each reported in fewer than 5 cases. The mean time from polystyrene administration to the onset of symptoms was 5.5 d.

Chronic kidney disease was reported in 37 (63.7%) patients, followed by hypertension (34.4%) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (20.6%). Strikingly, 75.8% of patients had some form of kidney disease, such as acute kidney injury, chronic kidney disease, end-stage renal disease, or had undergone kidney transplantation. The mean potassium levels prior to treatment initiation were 6.5 mmol/L.

The most commonly affected sites of inflammation were the cecum, rectum, and small intestine, accounting for 31%, 25.8%, and 22.4% of cases, respectively. Colonoscopy was mentioned in 28 (48.2%) of the reports, with biopsy being performed in 51 (87.9%) patients. Detailed findings from these diagnostic procedures are summarized in Table 2.

| Ref. | Country | Age (yr) | Sex | Polystyrene type | Total dose (g) | First symptom (d) | Symptoms | Gastrointestinal compromise | Colonoscopy | Histology | Outcomes |

| Patel et al[52], 2017 | United States | 45 | M | Kayexalate | 30 | - | None | Small intestine, cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon | Large ulcers at terminal ileum hepatic flexure and rectum | Small bowel: Acute enteritis and basophilic crystals with “fish-scales” | Recovery |

| Mizukami et al[53], 2016 | Japan | 64 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 30 | Hematochezia | Rectum | Multiple ulcers were found in the upper to mid-rectum | Rectum: SPS crystals | Recovery |

| Rogers et al[33], 2001 | United States | 55 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 5 | Diarrhea, Melena, Abdominal Pain | Sigmoid colon, descending colon | Large rectal ulcer and surrounding edematous and boggy mucosa | Rectum: Acute transmural necrosis with inflammatory and necrotic debris on the surface. Crystalloid foreign materials that were adherent to the ulcer bed | Recovery |

| Cervoni et al[54], 2015 | United States | 58 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 21 | None | Descending colon | Severely friable mucosa with ischemic- appearing ulceration and apparent site of perforation in the proximal descending colon | Descending colon: Basophilic crystals with a mosaic pattern resembling fish scales | Recovery |

| Singla et al[55], 2016 | United States | 50 | F | Kalimate | 15 | 2 | Constipation, Abdominal Pain, Bowel Sounds Were Absent | Cecum | NR | Cecum: Colonic necrosis and presence of SPS crystals in necrotic colonic mucosa | Recovery |

| Buraphat et al[34], 2019 | Thailand | 61 | M | Kayexalate | 210 | NR | Constipation, Abdominal Pain | Small intestine | NR | Small intestine: Multiple erosions with ischemic changes and basophilic angulated crystals on the surface, Sigmoid Colon: numerous basophilic angulated crystals with a fish scale appearance were observed adhering to the surface of the mucosa | Death |

| Buraphat et al[34], 2019 | Thailand | 74 | F | Kayexalate | 150 | NR | Abdominal Pain | Cecum | NR | NR | Death |

| Buraphat et al[34], 2019 | Thailand | 89 | F | Kayexalate | 180 | NR | Constipation, Abdominal Pain | Sigmoid colon | NR | NR | Recovery |

| Fiel et al[19], 2018 | Brazil | 56 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 7 | Constipation, Abdominal Pain, Fatigue, Abdominal Distension, Pneumoperitoneum, Hypokalemia CPS Bezoar | Cecum | NR | Serositis and transmural ischemia | Death |

| Jacob et al[1], 2016 | India | 75 | M | Kalimate | NR | 7 | Abdominal Pain | Sigmoid colon | Inflamed edematous and ulcerated cecum, small ulcer with slough 4–5 cm from anal verge rectum, Stricture in splenic flexure scope could not be passed beyond, nodularity with superficial ulceration in rectum, ulcers in rectum and sigmoid colon | All biopsies showed similar findings with ulceration and inflammatory granulation tissue in most. Crystals which were basophilic and irregular ranging from 1 to 200 in number, ranging in size from 50 to 150 μ were noted. They had a mosaic or ribbed pattern or both | Recovery |

| Jacob et al[1], 2016 | India | 72 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 7 | Abdominal Pain | Rectum | NR | Equal above | Recovery |

| Jacob et al[1], 2016 | India | 72 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 7 | Abdominal Pain | Rectum | NR | Equal above | Recovery |

| Jacob et al[1], 2016 | India | 64 | F | Kayexalate | NR | 7 | NR | Descending colon | NR | Equal above | Recovery |

| Jacob et al[1], 2016 | India | 48 | F | Kayexalate | NR | 7 | NR | Rectum | NR | Equal above | Death |

| Jacob et al[1], 2016 | India | 52 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 7 | NR | Sigmoid, Rectum | NR | Equal above | Death |

| Joo et al[8], 2009 | South Korea | 34 | F | Kayexalate | 215 | 2 | Hematochezia | Descending colon | Diffuse active ulceration with mucosal necrosis and hemorrhage from the rectum to beyond the reach of an endoscope | Colitis with mucosal necrosis or ulceration and irregular shaped and sized angulated crystals with a characteristic crystalline mosaic pattern on the mucosa and ulcer bed tissue and within the necroinflammatory debris | Death |

| Akagun et al[56], 2011 | Turkey | 78 | F | Kayexalate | 60 | 2 | Abdominal Pain, Pneumoperitoneum | Sigmoid colon | NR | Necroinflammatory debris and various sized fragments of basophilic crystalloid material with angulated margins on microscopic examination | Recovery |

| Cheng et al[20], 2021 | Australia | 53 | F | Kayexalate | 30 | 15 | Diarrhea, Vomiting, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension, Fever, Pneumoperitoneum | Transverse colon | NR | Multiple discrete areas of deep ulceration with intramural necrosis abscess formation and focal transmural penetration SPS crystals were present in the inflammatory debris | Death |

| Castillo-Cejas et al[57], 2014 | Spain | 73 | M | Kayexalate | NR | NR | Hypotension | Cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon | Ischemic lesions in cecum, ascending colon and hepatic angle | Ascending colon: Mucosal necrosis and Kalimate crystals with their characteristic mosaic pattern within the granulation tissue from one of the colonic ulcers | Recovery |

| Thomas et al[23], 2009 | United States | 64 | F | Kayexalate | 90 | 27 | Hematochezia, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension, Hypotension | Sigmoid colon, Rectum | Friable area of 15 to 25 cm from the anal verge | Rectum: Ulcerated mucosa and prominent granulation tissue with small eosinophilic angulated crystals embedded in mucosal ulcers | Recovery |

| Bomback et al[31], 2009 | United States | 56 | F | Kayexalate | 15 | NR | Abdominal Pain | Transverse colon | Large sessile mass in the midtransverse colon | Transverse colon: Crypt miniaturization with leakage of red blood cells and fibrin into the lamina propria associated with polygonal basophilic crystals | Recovery |

| Scott et al[37], 1993 | United States | 48 | M | Kayexalate | 50 | 0.5 | Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension | Descending colon, Sigmoid colon, Rectum | The rectum, sigmoid, and left colonic mucosa were erythematous and friable. The mucosa became frankly necrotic at the splenic flexure | NR | Recovery |

| Chou et al[58], 2011 | Taiwan | 30 | M | Kayexalate | 90 | 3 | Hematochezia | Transverse colon | Colon ulcers included scattered erosion longitudinal ulcerations and sharply defined segment of involvement | Transverse colon and splenic flexure: Necrotic debris adjacent to eroded colonic mucosa. A few basophilic and rhomboid crystals with fish-scale-like mosaic pattern were identified | Recovery |

| Ribeiro et al[59], 2017 | Portugal | 72 | M | Kalimate | NR | 1 | Abdominal Pain | Cecum, ascending colon | Congestive and ulcerated mucosa in the right colon and a deep necrotic ulcer in the cecum, with a diameter of 40 mm | Cecum: Necroinflammatory and granulation tissue containing basophilic-stained polystyrene sulfonate crystals | Recovery |

| Wootton et al[60], 1989 | United States | 48 | M | Keyexalate | 200 | 0.5 | Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension, Fever | Transverse colon | NR | Transverse colon: Patchy transmural infarction of the colon. Near the necrotic mucosa were large quantities of amorphous Kayexalate material | Recovery |

| Chelcun et al[61], 2012 | United States | 51 | M | Keyexalate | 30 | NR | Melena | Small intestine | Large ulcer surrounded by erythema was found at the ileocecal valve | Ileocecal valve: Reactive colonic mucosa with ulceration and prominent acute inflammatory exudate containing basophilic crystals consistent with SPS use | Recovery |

| Tapia et al[62], 2009 | Switzerland | 71 | F | Kayexalate | 80 | 10 | Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain, Vomiting | Cecum, ascending colon | Segmental, circumscribed colitis in the cecum and at the left flexure | Cecum and left flexure: Segmental ulcers lightly distorted crypts with mucus depletion and fibrosis in the lamina propria accompanied by a mixed inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and some neutrophils. Colon fragments with the angular crystals/foreign bodies | Recovery |

| Trottier et al[63], 2009 | Canada | 24 | M | Kayexalate | 110 | 1 | Constipation, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension, Fever, Hypotension | Small intestine | NR | Ileum-multifocal, acute ulceration. Patchy transmural necrosis and SPS crystal deposition within the intestinal mucosa | Recovery |

| Kao et al[64], 2015 | Taiwan | 59 | M | Kalimate | 120 | 2 | Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension, Hypotension | Small intestine, Sigmoid colon | NR | Ileum-transmural necrosis and perforation with basophilic angulated crystals extending from the ulcerated luminal surface into the transmural | Death |

| Singhania et al[25], 2020 | United States | 30 | M | Kayexalate | 15 | 0.16 | Hematochezia, Vomiting, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension | All colon | NR | NR | NR |

| Goutorbe et al[65], 2011 | United States | 73 | M | Kalimate | 15 | 3 | Abdominal Pain, Hypotension, Tachycardia | Small intestine, cecum | NR | Transmural abscess massive inflammatory infiltrate, ulceration and inflammation of the ceca mucosa with a fibrinous and purulent coating. Small fray-purple or blue angulated crystals | Death |

| Gerstman et al[18], 1992 | United States | 43 | NR | Kayexalate | 50 | 2 | Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension, Confusion, Blood in the Gastric Aspirate | Cecum | NR | NR | Recovery |

| Gerstman et al[18], 1992 | United States | 42 | NR | Kayexalate | 135 | NR | Hematochezia, Abdominal Pain | Cecum | NR | NR | Recovery |

| Aguilera et al[66], 2000 | Spain | 83 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 1 | Abdominal Pain, Hypotension | Small intestine | NR | Transmural necrosis and in its course and in the peritoneal surface there are numerous basophilic crystals with hematoxylin | Death |

| Gardiner et al[30], 1997 | Canada | 66 | M | Kayexalate | 240 | NR | NR | Stomach, small intestine | NR | Coagulative necrosis of the mucosa with overlying purple rhomboid kayexalate crystals, submucosal edema and acute transmural inflammation | Death |

| Gardiner et al[30], 1997 | Canada | 71 | F | Kayexalate | 105 | NR | Hematochezia | Small intestine, ascending colon | NR | Hemorrhagic mucosal necrosis associated | Death |

| Pusztaszeri et al[67], 2007 | France | 87 | M | Kalimate | NR | NR | Abdominal Distension | Small intestine | NR | Kayexalate crystals, submucosal edema and acute transmural inflammation | NR |

| Islam et al[26], 2015 | United States | 71 | F | Kayexalate | 15 | 0.5 | Vomiting, Abdominal Pain, Nausea | Cecum | NR | Diffuse mucosal necrosis with dark purple crystals | Recovery |

| Kardashian et al[68], 2016 | United States | 65 | F | Kayexalate | NR | 2 | Hematochezia, Constipation, Abdominal Pain, Fatigue, Abdominal Distension | NR | NR | Dark purple SPS crystals | Recovery |

| Shahid et al[69], 2019 | United States | 78 | F | Kayexalate | 43 | 1 | Abdominal Pain | Cecum, ascending colon | NR | Findings of ischemic colitis with detached purple refractile material | Recovery |

| Strader et al[70], 2017 | United States | 60 | M | Kayexalate | NR | NR | Nr | Cecum | 4cm circumferential, ulcerating mass in the cecum partially obstructing the lumen as well | Biopsies in both areas reveal material morphologically consistent with kayexalate with associated colitis, ulceration and necroinflammatory debris, with no evidence of malignancy | Recovery |

| Albeldawi et al[71], 2014 | United States | 61 | M | Kayexalate | NR | NR | Hematochezia, Fatigue, Dizziness | Cecum | Evidence of colitis and localized ulcerations in the cecum | Revealed basophilic, non-polarizable, rhomboid-like crystals without evidence of necrosis | NR |

| Ofori et al[72], 2017 | United States | 80 | F | Kayexalate | NR | 7 | Hematochezia, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension | Transverse colon | Revealed lumen obstructing clot in the mid transverse colon with adjacent unhealthy mucosa which was bleeding upon contact. Scope could not be advanced safely past the large clot | NR | Recovery |

| Abramowitz et al[27], 2014 | United States | 70 | F | Kayexalate | NR | NR | Hematochezia | Rectum | Scattered diverticula throughout the colon and a 2 cm × 3 cm semi-circumferential friable rectal ulceration just proximal to the anorectal junction with active oozing of blood | Fragments of granulation tissue and crystalline fragments consistent with Kayexalate that were seen on the surface | NR |

| Rugolotto et al[73], 2007 | Italy | 0,01 | NR | Kayexalate | 6.8 | 4 | Abdominal Distension | Small intestine | NR | Ileum specimen showed multiple areas of trans-mural necrosis, whereas the lumen showed basophilic and Zihel–Neelsen stain positive angulated crystals surrounded by fibrinoid and giant cells exudates | Recovery |

| Edhi et al[74], 2018 | United States | 73 | M | Kayexalate | 30 | 1 | Abdominal Distension | Cecum, ascending colon, transverse colon, descending colon | Highly consistent with ischemic colitis in the descending colon | Inflamed and ulcerated colonic mucosa and basophilic, non-polarizable, angulated, intramucosal crystals, highly consistent with SPS induced ischemic colitis | Recovery |

| Chatelain et al[75], 2007 | France | 46 | M | Kayexalate | 150 | NR | Diarrhra, Hematochezia | Descending colon, Sigmoid colon, Rectum | Segmental ulcerations of the sigmoid colon | Ischemic colitis with ulcerations and transmural inflammation. Kayexalate crystals were present in the colonic lumen, adherent to ulcers. Thickened and fibrous submucosa containing numerous basophilic and purple polygonal crystals surrounded by macrophages and giant cells | Recovery |

| Oliveira et al[7], 2018 | Portugal | 83 | F | Kayexalate | NR | 2 | Diarrhea, Abdominal Pain | Rectum | Visualization of the rectum, a depressed area in the lower rectum, partially ulcerated, without apparent necrosis was found and biopsied | Presence of basophilic structures with mosaic pattern, 1ilar to fish scales, surrounded by an intense active chronic inflammatory infiltrate, aspects compatible with lesion caused by ion exchange resin deposition (Kayexalate Crystals) | Recovery |

| Florian et al[76], 2019 | United States | 69 | M | Kayexalate | NR | NR | Hematochezia | Cecum, Ascending colon | Extensive circumferential ulceration and pseudomembrane in the cecum and proximal ascending colon. Persistent ulcerations with erythematous friability in the same area | Revealed acute reactive epithelial atypia with embedded polystyrene sulfonate crystals | NR |

| Lee et al[77], 2017 | United States | 66 | F | Kayexalate | NR | 5 | Hematochezia | Rectum | Two relatively isolated ulcers located in the transverse colon and in the rectum | The rectal ulcer demonstrated findings of crystal-like structures suggestive of kayexalate crystals | Recovery |

| Chang et al[78], 2020 | United States | 66 | M | Kayexalate | 30 | NR | NR | Small intestine | NR | Acute ischemic enteritis featuring mucosal ulceration associated with crystals morphologically compatible with SPS, submucosal arterial and venous thrombosis and acute organizing serositis | Recovery |

| Moole et al[79], 2014 | United States | 80 | F | Kayexalate | 30 | 1 | Diarrhea, Hematochezia, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension | Sigmoid colon, Rectum | Severe well demarcated colitis in the rectosigmoid junction with a large amount of blood clots at the demarcation | Showed distal rectosigmoid ischemic colitis, with mucosal and focal submucosal necrosis and crystals consistent with Kayexalate | Recovery |

| Edhi et al[24], 2017 | United States | 78 | M | Kayexalate | NR | NR | NR | Transverse colon, Descending colon | Diffuse moderate inflammation in the descending colon, with severe inflammation in the transverse colon | Ulceration of the colonic mucosa with basophilic crystal consistent with SPS induced injury and no features of ischemia, infectious changes or granulomas | NR |

| Huang et al[80], 2011 | United States | 57 | M | Kayexalate | 160 | 5 | Constipation, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension | NR | NR | Demonstrated crystals characteristic of SPS toxicity and concluded that the patient’s bowel perforation was likely caused by SPS | Recovery |

| Gürtler et al[81], 2018 | Switzerland | 56 | M | Kayexalate | NR | 1 | Melena, Abdominal Pain | Small intestine | Gastroscopy demonstrated severe ulcerative duodenitis with no evidence of active bleeding | Revealed a severe erosive duodenitis. Abundant SPS crystals were detectable within the fibrinoleukocytic exudates of the duodenal ulcers and on the surface of the inconspicuous gastric mucosa | Recovery |

| Hajjar et al[29], 2018 | Canada | 48 | M | Kayexalate | NR | NR | Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension | Stomach | NR | Revealed the presence of fibrinoleukocytic debris with rhomboid, birefringent crystals, suggestive of Kayexalate in the gastric wall | Recovery |

| Almulhim et al[28], 2018 | Saudi Arabia | 64 | M | Kayexalate | 30 | 9 | Hematochezia, Melena, Abdominal Pain, Fatigue, Fever, Anemia | Descending colon, transverse colon | Findings were suggestive of right colon colitis with possible etiology of ischemia and necrotic appearing mucosa | Specimen was found to be granulated and contain SPS crystals | Recovery |

| Dunlap et al[5], 2016 | United States | 55 | F | Kayexalate | 30 | 2 | Diarrhea, Hematochezia, Abdominal Pain, Abdominal Distension, Peritonite | All colon | Flexible sigmoidoscopy, which identified several ulcerations that were biopsied, later revealing ischemic necrosis of the bowel | Diffusely hemorrhagic with extensive multifocal ulcerations. Crystalloid particles consistent with kayexalate were identified throughout the bowel wall | Recovery |

| dos Santos et al[12], 2021 | Brazil | 77 | F | Kayexalate | 120 | 4 | Diarrhea | Sigmoid colon | Revealed edema, enanthema, and erosion into the sigmoid colon | Typical fish scale-like SPS crystal | Recovery |

Out of the 59 patients, 29 (50%) required surgical intervention, with one patient necessitating reoperation. Among patients with available data, 39 (67.2%) experienced a favorable outcome, while 12 (20.6%) succumbed to the condition. The mean time to symptom resolution was 36.7 d, ranging from 1 to 120 d.

In the quality assessment of the included cases, 2 (3.3%) were classified as having low quality, while the remaining 57 (96.7%) were considered to have moderate quality. None of the cases were categorized as high quality.

This systematic review delves into the analysis of documented cases of SPS-induced colitis, shedding light on the importance of collecting data on medication-related adverse events to enhance healthcare safety. Hyperkalemia, if left untreated, poses significant threats such as severe arrhythmias, cardiac arrest, and fatality[11]. The use of SPS for managing hyperkalemia has a historical legacy dating back to the 1960s[12], even though robust evidence substantiating its safety and efficacy remains scant[2].

Notably, mild adverse effects associated with SPS include symptoms like diarrhea, constipation, abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, and vomiting[13]. In the systematic review, bloating was reported in 31% of cases as a minor adverse effect, while vomiting occurred in 7% of patients. However, it is crucial to distinguish these relatively well-tolerated mild effects from severe adverse outcomes potentially linked to SPS use, which can significantly increase morbidity and mortality[14]. Such severe outcomes encompass colitis, ischemic colonic necrosis, seizures, confusion, irregular heartbeat, and pneumoperitoneum[13]. This systematic review reveals that all the cases included presented with colitis, and some cases developed more severe consequences.

Interestingly, descriptions of intestinal lesions first emerged in 1987 when catastrophic colonic necrosis was documented in five cases[15,16]. Subsequently, in 2012, a cohort study involving 2194 inpatients identified colonic necrosis in 82 cases related to SPS use[17]. Studies have reported varying incidences of colon necrosis after drug administration, ranging from 0.14% to 1.8%, with a higher incidence observed in the postoperative period[5,18]. Additionally, other concerning findings associated with SPS use, such as the three cases of pneumoperitoneum requiring urgent laparotomy, have been reported[19,20]. The characteristics of the patients are detailed in Tables 1 and 2.

Although these cases, though less common, are often detected early due to patients' complaints of increased abdominal pain and distention[5]. Typically, the time to the initial manifestation is around two days. A retrospective cohort study involving 19530 adults found that new users and users receiving the recommended dose 'per label' had a higher risk of adverse effects compared to chronic users and those on lower doses[21,22]. After adjusting for 26 covariates, SPS use was associated with hospitalization or death due to intestinal ischemia/thrombosis or gastrointestinal ulcers and perforation (HR 1.25, 95%CI 1.05-1.49)[21,22]. Therefore, the threshold dose for deleterious effects has yet to be determined, and caution is advised when prescribing this medication, especially for more fragile patients[4].

In a prior systematic review, 91% of included cases had a history of renal disease, a proportion slightly higher than the 75.8% observed in this study[4]. This aligns with expectations, as SPS is commonly used in patients with renal conditions. Other common comorbidities identified in our work included hypertension and diabetes mellitus, both of which are associated with chronic kidney disease[8,23,24]. In the literature, potential risk factors associated with deleterious adverse effects include uremia, hypovolemia, peripheral vascular disease, and immunosuppressive therapy, all of which were also evident in the cases reviewed[18,25-28].

Typically, the colon is the gastrointestinal segment most frequently affected by SPS-induced complications. These lesions necessitate endoscopic/colonoscopy analysis with biopsy to rule out differential diagnoses, such as cancer[16]. Gastric involvement is less common and was identified in only two cases in our review[29,30]. Biopsy results typically reveal intestinal necrosis, ulcers, or perforations, with an accumulation of SPS crystals in more than 90% of tissue samples[5]. The presence of kayexalate crystals in pathology specimens differentiates kayexalate-induced necrosis from ischemic necrosis[5]. Histologic evidence of angulated crystals of sodium polystyrene sulfate in areas of mucosal erosions, ulcerations, or frank necrosis strongly suggests the diagnosis[31]. Other associated findings include inflammatory exudates, pseudomembrane formation, and acute/chronic serositis[32]. These crystals are typically identified adhered to the mucosa or embedded within the inflammatory milieu and ulcerations[5]. Thus, to arrive at a definitive diagnosis, it is imperative to rule out conditions that can mimic SPS-induced effects, such as neoplasms, inflammatory diseases, and infectious diseases[16]. These histological characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

However, the pathophysiological mechanism underlying these lesions remains incompletely understood[4]. One of the most widely accepted theories suggests that the presence of renin in high concentrations among patients with renal failure plays a pivotal role. Activation of renin and subsequent splanchnic vasoconstriction can lead to non-occlusive mesenteric ischemia, predisposing the colonic mucosa to injuries and electrolyte disturbances[32,33]. Nevertheless, it remains unclear why patients with renal failure are more susceptible to this catastrophic complication. It may simply be attributed to their higher likelihood of being hyperkalemic, necessitating treatment with higher doses of SPS than other patients[33].

Alternative theories propose that polystyrene's high water affinity leads to bulk formation with shear-thickening flow behavior, resulting in clumping and resin clogging, particularly in patients with compromised gastrointestinal motility[34]. This leads to resin impaction, subsequent gut obstruction, ischemic necrosis, and perforation, analogous to findings in stercoral colonic perforation[35]. Details about the drug are available in Table 3.

| Indications | Mechanism of action | Administration | Dose (g) | Adverse effects (mild) | Adverse effects (serious) | Contraindications |

| Hyperkalemia | Resin exchanges sodium with potassium ions from the intestinal cells | Orally or rectally | Usually, 15 to 60 daily | Diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, bloating | Ischemic colonic necrosis, constipation, seizures, confusion, abdominal pain, irregular heart beat | Hypokalemia, previous hypersensitivity to SPS, bowel obstruction, neonates with reduced gut motility |

Despite the relatively common use of SPS, there is limited evidence regarding its effectiveness and safety in the literature. Therefore, vigilance is warranted regarding the drug's adverse effects[36]. A previous systematic review published in 2013 reported serious adverse reactions associated with colonic necrosis, which occupied a prominent position and resulted in a mortality rate of 33% among affected patients, higher than the 21% mortality rate observed in our study[4]. Conversely, in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial, colonic necrosis was not reported[3]. However, the trial involved only 31 participants who were followed for a short period (7 d) and were less ill than the general patients who typically receive the medication[32]. Therefore, prescribing SPS should be a carefully considered decision, taking into account each patient's specific circumstances, especially in cases of sicker patients, such as older individuals and those with gastrointestinal hypomotility. Higher mortality rates have been observed in colitis induced by SPS. Therefore, it is essential to consider alternative approaches for controlling hyperkalemia. If alternative options are not available, it is strongly advised to implement routine monitoring to enable early detection of potential complications[19,36].

In the adapted quality assessment tool, the majority of cases were classified as having moderate quality (96.6%)[10]. None of the cases were categorized as high quality. This was primarily due to causality questions, which, for example, implicate the danger of reexposing the patient to SPS. Additionally, none of the cases met the criteria to score in question one, as the authors did not specify whether the cases were unique in their centers. Nonetheless, only two cases were classified as low quality[34,37]. Further details can be found in Supplementary material.

The primary limitations of our study were the limited number of available cases (n = 59) and the scarcity of data in many of the reviewed cases. Despite our efforts, some full articles could not be located, even after contacting the authors, which could be attributed to the publication year. The inclusion of articles was restricted to those published in English, Spanish, French, or Portuguese, potentially resulting in the omission of articles in other languages. Despite these limitations, most of the variables presented in Tables 1 and 2 provide valuable insights into the characteristics of the patients.

Considering that observational trials suggest that SPS may lower serum potassium levels, but not without the risk of bowel injury[2] and death resulting from hyperkalemia is an unacceptable outcome[38], alternative options for addressing elevated potassium levels should be explored, and SPS should be considered a drug of last resort[39]. Some authors argue that despite many decades of experience with SPS and its low cost, it would be premature to abandon it in favor of more expensive alternatives with similar side effects or undefined long-term toxicity[17]. When evaluating patients exposed to SPS with diarrhea, it is essential to always consider a broad range of potential differential diagnoses for colitis and diarrhea in this group of patients, such as inflammatory bowel disease[40-42], infectious enteritis and colitis[43-45], angiotensin II receptor blocker induced sprue-like enteropathy[46], celiac disease[47,48], foreign body ingestion or food poisoning[49], neoplasm[50] or pellagra[51].

In conclusion, alternative methods such as hemodialysis or glucose, insulin, or bicarbonate injections may be more effective in controlling hyperkalemia[18]. There is currently insufficient high-quality data to estimate the number of adverse events associated with SPS use, making it challenging to determine whether the benefits outweigh the risks[2,38]. Moreover, it is crucial to acknowledge that the mortality rate was notably significant, standing at 20.6% in this review. Therefore, future studies should ideally involve randomized controlled trials with an adequate number of patients to investigate the real risks and benefits of this drug.

The study details the significance of Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate (SPS) in managing hyperkalemia, a life-threatening condition. SPS, used to remove excess potassium, has side effects, including severe gastrointestinal complications. The exact mechanism of SPS-induced colitis is unclear, but it primarily affects the colon, requiring biopsy for diagnosis.

Comprehensive understanding of the SPS therapy and colitis relationship is crucial for patient safety. This research addresses knowledge gaps, aiming to contribute to future studies in drug safety and gastroenterology.

This study's main goal is to systematically review cases of SPS-induced colitis to understand its prognosis and influencing factors. Achieving these objectives enhances awareness of risks tied to SPS therapy, aiding clinical decisions for hyperkalemia management and guiding future research on risk mitigation.

This systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines for transparency and methodological rigor. A comprehensive search strategy covered multiple databases and utilized manual searches. Inclusion criteria prioritized case reports or case series studies, with language inclusion restricted to English, Spanish, French, or Portuguese. A two-step screening process and data extraction by independent reviewers ensured rigorous analysis. Methodological quality assessment employed a modified tool, addressing specific aspects related to polystyrene-induced colitis. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, providing a comprehensive dataset characterization.

The review examined 442 references, including 51 which comprised 59 cases meeting the criteria. The majority of cases were from the United States (48.2%). The patients age varied from less than 1 year to 89 years and were predominantly diagnosed with SPS-induced colitis. Common symptoms included abdominal pain, bloating, and gastrointestinal issues, with chronic kidney disease being prevalent. Diagnostic procedures such as colonoscopy and biopsies were frequently conducted. Surgical intervention was necessary for 50% of patients, and most had favorable outcomes, with a mean time to symptom resolution of 36.7 days.

This systematic review underscores the importance of monitoring adverse events related to SPS in hyperkalemia treatment. It differentiates mild from severe side effects, advocating for alternative hyperkalemia management, especially for older or fragile patients due to higher associated mortality. The exact mechanisms remain unclear, but factors such as renin concentration and water affinity are implicated.

Future research should prioritize randomized controlled trials to assess SPS use, considering its effectiveness and risks. Alternative hyperkalemia management methods and cautious SPS prescription are crucial, with a focus on addressing knowledge gaps for informed clinical decisions.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Corresponding Author's Membership in Professional Societies: Federação Brasileira De Gastroenterologia; Grupo de Estudos da Doença Inflamatória Intestinal do Brasil.

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: United Kingdom

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chiba T, Japan; Huang HM, China S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Yu HG

| 1. | Jacob SS, Parameswaran A, Parameswaran SA, Dhus U. Colitis induced by sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol: A report of six cases. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2016;35:139-142. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gupta AA, Self M, Mueller M, Wardi G, Tainter C. Dispelling myths and misconceptions about the treatment of acute hyperkalemia. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;52:85-91. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lepage L, Dufour AC, Doiron J, Handfield K, Desforges K, Bell R, Vallée M, Savoie M, Perreault S, Laurin LP, Pichette V, Lafrance JP. Randomized Clinical Trial of Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate for the Treatment of Mild Hyperkalemia in CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:2136-2142. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 109] [Article Influence: 12.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Harel Z, Harel S, Shah PS, Wald R, Perl J, Bell CM. Gastrointestinal adverse events with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) use: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2013;126:264.e9-264.24. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 200] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 206] [Article Influence: 18.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Dunlap RH, Martinez R. Total colectomy for colon perforation after kayexalate administration: a case report and literature review of a rare complication. J Surg Case Rep. 2016;2016. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Palaka E, Leonard S, Buchanan-Hughes A, Bobrowska A, Langford B, Grandy S. Evidence in support of hyperkalaemia management strategies: A systematic literature review. Int J Clin Pract. 2018;72. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Oliveira AA, Pedro F, Craveiro N, Cruz AV, Almeida RS, Luís PP, Santos C. Rectal ulcer due to Kayexalate deposition - an unusual case. Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2018;64:680-683. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Joo M, Bae WK, Kim NH, Han SR. Colonic mucosal necrosis following administration of calcium polystryrene sulfonate (Kalimate) in a uremic patient. J Korean Med Sci. 2009;24:1207-1211. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 58] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA; PRISMA-P Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15040] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13974] [Article Influence: 1552.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Murad MH, Sultan S, Haffar S, Bazerbachi F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23:60-63. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1008] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1230] [Article Influence: 205.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Montford JR, Linas S. How Dangerous Is Hyperkalemia? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;28:3155-3165. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 111] [Article Influence: 15.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Dos Santos FS, Aver GP, Paim TV, Riva F, Brambilla E, Soldera J. Sodium-Polystyrene Sulfonate-Induced Colitis. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2023;30:153-155. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Rahman S, Marathi R. Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate. 2023 Jul 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Noel JA, Bota SE, Petrcich W, Garg AX, Carrero JJ, Harel Z, Tangri N, Clark EG, Komenda P, Sood MM. Risk of Hospitalization for Serious Adverse Gastrointestinal Events Associated With Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate Use in Patients of Advanced Age. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1025-1033. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 88] [Article Influence: 17.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lillemoe KD, Romolo JL, Hamilton SR, Pennington LR, Burdick JF, Williams GM. Intestinal necrosis due to sodium polystyrene (Kayexalate) in sorbitol enemas: clinical and experimental support for the hypothesis. Surgery. 1987;101:267-272. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | Abraham SC, Bhagavan BS, Lee LA, Rashid A, Wu TT. Upper gastrointestinal tract injury in patients receiving kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulfonate) in sorbitol: clinical, endoscopic, and histopathologic findings. Am J Surg Pathol. 2001;25:637-644. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 150] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 182] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Watson MA, Baker TP, Nguyen A, Sebastianelli ME, Stewart HL, Oliver DK, Abbott KC, Yuan CM. Association of prescription of oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate with sorbitol in an inpatient setting with colonic necrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:409-416. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 62] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gerstman BB, Kirkman R, Platt R. Intestinal necrosis associated with postoperative orally administered sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol. Am J Kidney Dis. 1992;20:159-161. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 119] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Fiel DC, Santos I, Santos JE, Vicente R, Ribeiro S, Silva A, Malvar B, Pires C. Cecum perforation associated with a calcium polystyrene sulfonate bezoar - a rare entity. J Bras Nefrol. 2019;41:440-444. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Cheng ES, Stringer KM, Pegg SP. Colonic necrosis and perforation following oral sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Resonium A/Kayexalate in a burn patient. Burns. 2002;28:189-190. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Labriola L, Jadoul M. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate: still news after 60 years on the market. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1455-1458. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Laureati P, Xu Y, Trevisan M, Schalin L, Mariani I, Bellocco R, Sood MM, Barany P, Sjölander A, Evans M, Carrero JJ. Initiation of sodium polystyrene sulphonate and the risk of gastrointestinal adverse events in advanced chronic kidney disease: a nationwide study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2020;35:1518-1526. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 13.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Thomas A, James BR, Landsberg D. Colonic necrosis due to oral kayexalate in a critically-ill patient. Am J Med Sci. 2009;337:305-306. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Edhi AI, Sharma N, Hader I, Fisher A, Patel A. Sodium Polystyrene Sulfate-Induced Colonic Ulceration: 1490. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:S815-S816. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Singhania N, Al-Odat R, Singh AK, Al-Rabadi L. Intestinal necrosis after co-administration of sodium polystyrene sulfonate and activated charcoal. Clin Case Rep. 2020;8:722-724. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Islam M, Moradi D, Behuria S. Kayexalate-Induced Bowel Necrosis: A Rare Complication From a Common Drug: 311. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:S135-S136. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Abramowitz M, El Younis C. Kayexalate-Induced Rectal Ulceration as a Cause of Rectal Bleeding in a Non-uremic Patient: 1370. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:S404. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Almulhim AS, Hall E, Mershid Al Rehaili B, Almulhim AS. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate induced intestinal necrosis; a case report. Saudi Pharm J. 2018;26:771-774. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Hajjar R, Sebajang H, Schwenter F, Mercier F. Sodium polystyrene sulfonate crystals in the gastric wall of a patient with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and gastric perforation: an incidental finding or a pathogenic factor? J Surg Case Rep. 2018;2018:rjy138. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gardiner GW. Kayexalate (sodium polystyrene sulphonate) in sorbitol associated with intestinal necrosis in uremic patients. Can J Gastroenterol. 1997;11:573-577. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Bomback AS, Woosley JT, Kshirsagar AV. Colonic necrosis due to sodium polystyrene sulfate (Kayexalate). Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:753.e1-753.e2. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Dantas E, Coelho M, Sequeira C, Santos I, Martins C, Cardoso C, Freire R, Oliveira AP. Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding Associated With Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate Use. ACG Case Rep J. 2021;8:e00585. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Rogers FB, Li SC. Acute colonic necrosis associated with sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate) enemas in a critically ill patient: case report and review of the literature. J Trauma. 2001;51:395-397. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Buraphat P, Niyomnaitham S, Pongpaibul A, Maneerattanaporn M. Calcium polystyrene sulfonate-induced gastrointestinal tract necrosis and perforation. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2019;82:542-543. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Takeuchi N, Nomura Y, Meda T, Iida M, Ohtsuka A, Naba K. Development of Colonic Perforation during Calcium Polystyrene Sulfonate Administration: A Case Report. Case Rep Med. 2013;2013:102614. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Leaf DE, Cheng XS, Sanders JL, Mendu M, Schiff GD, Mount DB, Bazari H. An electronic alert to decrease Kayexalate ordering. Ren Fail. 2016;38:1752-1754. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Scott TR, Graham SM, Schweitzer EJ, Bartlett ST. Colonic necrosis following sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate)-sorbitol enema in a renal transplant patient. Report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:607-609. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 56] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Watson M, Abbott KC, Yuan CM. Damned if you do, damned if you don't: potassium binding resins in hyperkalemia. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1723-1726. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 73] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sterns RH, Rojas M, Bernstein P, Chennupati S. Ion-exchange resins for the treatment of hyperkalemia: are they safe and effective? J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:733-735. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 199] [Article Influence: 14.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Brambilla B, Barbosa AM, Scholze CDS, Riva F, Freitas L, Balbinot RA, Balbinot S, Soldera J. Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis and Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Case Report and Systematic Review. Inflamm Intest Dis. 2020;5:49-58. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Ballotin VR, Bigarella LG, Riva F, Onzi G, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Soldera J. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and autoimmune hepatitis overlap syndrome associated with inflammatory bowel disease: A case report and systematic review. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8:4075-4093. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Dall'Oglio VM, Balbinot RS, Muscope ALF, Castel MD, Souza TR, Macedo RS, Oliveira TB, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Brambilla E, Soldera J. Epidemiological profile of inflammatory bowel disease in Caxias do Sul, Brazil: a cross-sectional study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2020;138:530-536. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | da Cruz ER, Forno AD, Pacheco SA, Bigarella LG, Ballotin VR, Salgado K, Freisbelen D, Michelin L, Soldera J. Intestinal Paracoccidioidomycosis: Case report and systematic review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2021;25:101605. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Soldera J. Disseminated histoplasmosis with duodenal involvement. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:453-454. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Kanika A, Soldera J. Pulmonary cytomegalovirus infection: A case report and systematic review. WJMA. 2023;11:151-166. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 46. | Soldera J, Salgado K. Gastrointerestinal: Valsartan induced sprue-like enteropathy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1262. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Soldera J, Salgado K, Pêgas KL. Refractory celiac disease type 2: how to diagnose and treat? Rev Assoc Med Bras (1992). 2021;67:168-172. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Soldera J, Coelho GP, Heinrich CF. Life-Threatening Diarrhea in an Elderly Patient. Gastroenterology. 2021;160:26-28. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Pante L, Brito LG, Franciscatto M, Brambilla E, Soldera J. A rare cause of acute abdomen after a Good Friday. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:9539-9541. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Fistarol CHDB, da Silva FR, Passarin TL, Schmitz RF, Salgado K, Soldera J. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding due to gastrointestinal stromal tumour of duodenum. GastroHep. 2021;3:169-171. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 51. | Moro C, Nunes C, Onzi G, Terres AZ, Balbinot RA, Balbinot SS, Soldera J. Gastrointestinal: Life-threatening diarrhea due to pellagra in an elderly patient. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1465. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Patel S, Arnold CA, Gray DM. A Case of Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate (Kayexalate)-Induced Bowel Ischemia: A Reminder of Adverse Effects of a Common Medication: 2501. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG. 2017; 112: S1365. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 53. | Mizukami H, Matsushima M, Motegi E, Nakahara F, Kijima M, Uchida T, Koike J, Igarashi M, Mine T. A rare case of rectal ulcer bleeding after taking sodium polystyrene sulfonate. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology: wiley-blackwell 111 river st, hoboken 07030-5774, nj usa; 2016; 189-189. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 54. | Cervoni G, Hughes SJ. An unusual case of colonic hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:e4-e5. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Singla M, Shikha D, Lee S, Baumstein D, Chaudhari A, Carbajal R. Asymptomatic Cecal Perforation in a Renal Transplant Recipient After Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate Administration. Am J Ther. 2016;23:e1102-e1104. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Akagun T, Yazici H, Gulluoglu MG, Yegen G, Turkmen A. Colonic necrosis and perforation due to calcium polystyrene sulfonate in a uraemic patient: a case report. NDT Plus. 2011;4:402-403. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Castillo-Cejas MD, de-Torres-Ramírez I, Alonso-Cotoner C. Colonic necrosis due to calcium polystyrene sulfonate (Kalimate) not suspended in sorbitol. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2013;105:232-234. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Chou YH, Wang HY, Hsieh MS. Colonic necrosis in a young patient receiving oral kayexalate in sorbitol: case report and literature review. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2011;27:155-158. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Ribeiro H, Pereira E, Banhudo A. Colonic Necrosis Induced by Calcium Polystyrene Sulfonate. GE Port J Gastroenterol. 2018;25:205-207. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Wootton FT, Rhodes DF, Lee WM, Fitts CT. Colonic necrosis with Kayexalate-sorbitol enemas after renal transplantation. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:947-949. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Chelcun JL, Sable RA, Friedman K. Colonic ulceration in a patient with renal disease and hyperkalemia. JAAPA. 2012;25:34, 37-38. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Tapia C, Schneider T, Manz M. From hyperkalemia to ischemic colitis: a resinous way. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:e46-e47. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Trottier V, Drolet S, Morcos MW. Ileocolic perforation secondary to sodium polystyrene sulfonate in sorbitol use: a case report. Can J Gastroenterol. 2009;23:689-690. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Kao CC, Tsai YC, Chiang WC, Mao TL, Kao TW. Ileum and colon perforation following peritoneal dialysis-related peritonitis and high-dose calcium polystyrene sulfonate. J Formos Med Assoc. 2015;114:1008-1010. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Goutorbe P, Montcriol A, Lacroix G, Bordes J, Meaudre E, Souraud JB. Intestinal Necrosis Associated with Orally Administered Calcium Polystyrene Sulfonate Without Sorbitol. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45:e13. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Aguilera B, Alcaraz R. Necrosis intestinal asociada a la administración de sulfonato de poliestireno sódico. Presentación de un Caso. Rev Esp Patol. 2000;33:171-174. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 67. | Pusztaszeri M, Christodoulou M, Proietti S, Seelentag W. Kayexalate Intake (in Sorbitol) and Jejunal Diverticulitis, a Causative Role or an Innocent Bystander? Case Rep Gastroenterol. 2007;1:144-151. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Kardashian AA, Lane J. Kayexalate-induced Colitis Presenting as a Mass-like Lesion: 1432. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:S651-S652. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 69. | Shahid T, Abbas SH, Hertan H. 1595 Kayexalate-Induced Colitis: A Rare Cause of Acute Abdomen! Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:S889-S890. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 70. | Strader M, Jackson M, Ashley C, Yoon E. Kayexalate-induced Colitis: Further Insights into a Rare Condition: 1424. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:S775. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 71. | Albeldawi M, Gaur V, Weber L. Kayexalate-induced colonic ulcer. Gastroenterol Rep (Oxf). 2014;2:235-236. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 11] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Ofori E, Sunkara T, Gaduputi V. Kayexalate-Induced Ischemic Colitis: A Rare Entity: 2856. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:S1532. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 73. | Rugolotto S, Gruber M, Solano PD, Chini L, Gobbo S, Pecori S. Necrotizing enterocolitis in a 850 gram infant receiving sorbitol-free sodium polystyrene sulfonate (Kayexalate): clinical and histopathologic findings. J Perinatol. 2007;27:247-249. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Edhi AI, Cappell MS, Sharma N, Amin M, Patel A. One Oral Dose of Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate Associated with Ischemic Colitis and Crystal Deposition in Colonic Mucosa. ACG Case Rep J. 2018;5:e74. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Chatelain D, Brevet M, Manaouil D, Yzet T, Regimbeau JM, Sevestre H. Rectal stenosis caused by foreign body reaction to sodium polystyrene sulfonate crystals (Kayexalate). Ann Diagn Pathol. 2007;11:217-219. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Florian R, Jackson C. 1454 Recurrent Isolated Colon Ischemia Secondary to Kayexlate. Kayexelate Helps History to Repeat Itself. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:S806-S807. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 77. | Lee F, Jahng A. Simultaneous CMV Colitis and Kayexalate-Induced Ulcer Presenting as Hematochezia: 1591. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:S868-S869. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 78. | Chang BSF, Paz HA, Jhaveri K, Mechery V, Bijol V, Hirsch J, Barnett R. Small bowel necrosis associated with a single dose kayexalate treatment in a patient with chronic sevelamer therapy. AJKD. 1800;2020:569-70. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Moole H, Ahmed Z, Aiyer M, Puli S, Dhillon S. Sodium Polysterone Sulfonate-Induced Colonic Mucosal Necrosis in a Hypovolemic Patient With Acute Kidney Injury: 1410. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:S417. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 80. | Huang W, Volles D, Ally W. 886: sodium polystyrene sulfonate (kayexalate) associated bowel perforation. Critical Care Medicine. 39:248. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Gürtler N, Hirt-Minkowski P, Brunner SS, König K, Glatz K, Reichenstein D, Bassetti S, Osthoff M. Sodium Polystyrene Sulfonate and Cytomegalovirus-Associated Hemorrhagic Duodenitis: More than Meets the Eye. Am J Case Rep. 2018;19:912-916. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |