Published online Sep 16, 2015. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v3.i9.838

Peer-review started: March 25, 2015

First decision: April 10, 2015

Revised: April 21, 2015

Accepted: June 4, 2015

Article in press: June 8, 2015

Published online: September 16, 2015

Patients with prosthetic cardiac valves are at high risk for thromboembolic complications and need life long anticoagulation with warfarin, which can be associated with variable dose requirements and fluctuating level of systemic anticoagulation and may predispose to thromboembolic and or hemorrhagic complications. Prosthetic cardiac valve thrombosis is associated with high morbidity and mortality. A high index of suspicion is essential for prompt diagnosis. Transthoracic echocardiography, and if required transesophageal echocardiography are the main diagnostic imaging modalities. Medically stable patients can be managed with thrombolytic therapy and anticoagulation, while some patients may require surgical thrombectomy or valve replacement. We present a case report of a patient with prosthetic mitral valve and an unusually large left atrial thrombus with both thromboembolic and hemorrhagic complications.

Core tip: Patients with mechanical prosthetic cardiac valves require life long systemic anticoagulation. Maintaining therapeutic anticoagulation consistently is challenging, given the variable dose requirements with warfarin, especially with dietary changes and drug interactions. We present a case of a patient with fluctuating control of anticoagulation, which led to an unusually large horseshoe thrombus in her left atrium and subsequent cerebrovascular complications. We also provide a review of literature, diagnostic modalities and treatment options.

- Citation: Mehra S, Movahed A, Espinoza C, Marcu CB. Horseshoe thrombus in a patient with mechanical prosthetic mitral valve: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2015; 3(9): 838-842

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v3/i9/838.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v3.i9.838

Patients with prosthetic cardiac valves are at high risk for thromboembolic complications and need life long anticoagulation with warfarin. Thrombosis of a mechanical prosthetic cardiac valve is a serious complication with high morbidity and mortality. Advancements in valve design and surgical techniques have improved prognosis but thrombo-embolism remains a source of complications in patients with mechanical prosthetic cardiac valves[1,2]. Warfarin is the only oral anticoagulant approved for systemic anticoagulation in patients with prosthetic cardiac valves. However, warfarin has been associated with variable dose requirements related to common genetic polymorphisms influencing their metabolism, varying amounts of dietary intake of vitamin K and interactions with other drugs being used concomitantly[3-5]. Fluctuating level of systemic anticoagulation may predispose to thromboembolic and or hemorrhagic complications. We present a case of a patient with a mechanical bi-leaflet mitral valve prosthesis who presented to our institution with an unusually shaped and large sized left atrial thrombus. The case exemplifies a recognized complication in this patient population and is followed by a review of literature including pathogenesis, clinical presentation and treatment options.

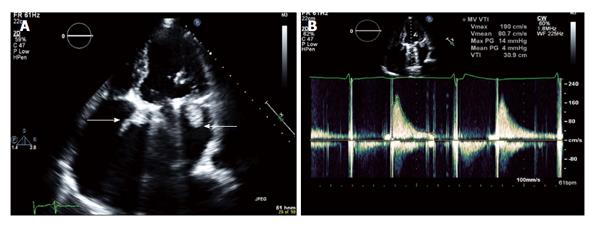

A 77-year-old female with medical history of severe rheumatic mitral stenosis treated with mitral valve replacement with 31 mm St. Jude mechanical bileaflet valve was brought to our emergency room with acute onset of right sided weakness and altered mental status by emergency medical services (EMS). Per a family member patient had complained of not feeling well and while EMS was being contacted, she became unresponsive. EMS intubated the patient for airway protection. Upon arrival to our hospital the patient was unresponsive, with heart rate of 127/min, irregular rhythm, blood pressure of 127/55 mmHg and temperature of 36.6 degrees centigrade. On chest auscultation heart sounds were soft with no clear audible valve click. Bilateral lung air entry was decreased with scattered crepitations. Neurological examination revealed pupils reactive to light but deviated to the left and right arm and leg paralysis. The patient was admitted to the medical intensive care unit. Review of her medical record showed that she had labile control of systemic anticoagulation with warfarin, with international normalized ratio (INR) fluctuating between 1.4 to 3.5 in the past six months; INR was 2.3 on admission. Initial laboratory investigations revealed leukocytosis, with white blood cells at 34.4 k/mL, hemoglobin 10.1 g/dL, platelets 845 k/mL, sodium 144 meq/L, blood urea nitrogen 23 meq/L and serum creatinine 0.7 meq/L. Electrocardiogram showed atrial fibrillation with ventricular rate of 113/min, with non-specific ST changes. Blood cultures were obtained and the patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotic coverage. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the head revealed no acute changes but old bilateral cerebellar lacunar infarcts and mild diffuse atrophy. An urgent transthoracic echocardiogram (Figure 1A) showed an oval shaped echo density (1.3 cm × 2.4 cm) attached to the atrial side of the mitral valve in a dilated left atrial cavity, likely representing a thrombus. Mean and peak pressure gradients across the mitral valve were 4 and 14 mmHg respectively (Figure 1B), which were similar to the gradients post-valve implantation. The left ventricular systolic function was mildly decreased with ejection fraction of 40%-45%.

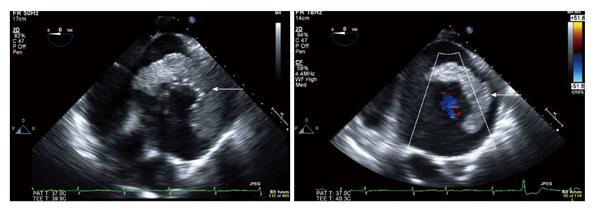

Subsequently transesophageal echocardiogram was performed which revealed a horseshoe shaped, partially mobile, echo density, consistent with thrombus around the sewing ring of the mechanical valve on the left atrial side (Figure 2). Neurology team recommended anticoagulation with therapeutic intravenous heparin at 12 units/kg body weight per hour without initial bolus. Meanwhile patient deteriorated clinically with hypotension not responsive to fluid challenge and decreasing urine output and patient was started on pressor support. Repeat CT scan of the head showed interval development of extensive hypodensity in the left frontal, parietal, insular and temporal lobes and involving the left basal ganglia, with associated petechial hemorrhages. Heparin was subsequently discontinued due to intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) seen on computed tomography of the head. The patient was initially anticoagulated with therapeutic intravenous heparin, which was subsequently discontinued due to ICH seen on computed tomography of the head. Thrombolytic therapy was contraindicated due to ICH. The patient passed away after withdrawal of life support per family’s wishes.

According to a meta-analysis by Cannegieter et al[6], the incidence of valve thrombosis in prosthetic heart valve recipients was 1 per 100 patient-years in patients on warfarin therapy and around four times higher in patients on no anticoagulation therapy. The incidence of thrombosis was twice as likely for prosthetic valves in the mitral position as compared to the aortic position. Caged ball valves have a higher incidence of thrombosis compared to tilting disc and bileaflet valves[6]. Lengyel[7] reported the incidence of prosthetic cardiac valve thrombosis to be between 1%-4% despite adequate anticoagulation. Prosthetic mechanical valves in the mitral or tricuspid position, first generation Ball-cage and tilting-disc mitral valves have higher incidence of thrombosis. The pathogenesis of thrombosis is likely multifactorial, depending upon the thrombogenic effect of prosthetic material, left atrial geometry and function, presence of atrial fibrillation, inadequate anticoagulation, altered transprosthetic blood flow and any other cause for hypercoagulable state such as malignancy or drugs[8-11]. Inadequate anticoagulation could be a result of variable dose requirements of warfarin. Three new oral anticoagulants (NOACs) - dabigatran, rivaroxaban and apixaban are approved for systemic anticoagulation for patients in atrial fibrillation but not approved for patients with prosthetic cardiac valves. NOACs have several advantages over warfarin, including less dietary interference with their metabolism, fewer drug interactions and a more predictable anticoagulant effect that allows for administration of NOACs in fixed doses without the need for routine coagulation laboratory monitoring[12]. The RE-ALIGN study evaluated the use of dabigatran in patients with mechanical heart valves. The trial was terminated early because of excess of thromboembolic and bleeding events among patients in the dabigatran group[13]. Hence despite shortcomings, warfarin is the only oral anticoagulant approved for anticoagulation in patients with prosthetic cardiac valves for now.

Clinical features suggestive of cardio-embolic source include sudden onset of symptoms, loss of consciousness at onset, rapid regression of symptoms, simultaneous or sequential strokes in different arterial territories, or evidence of embolism to other organs. Presence of bi-hemispheric cerebrovascular, combined anterior and posterior circulation, or bilateral or multilevel posterior circulation infarcts on CT scan of the head are suggestive of cardioembolism[14]. In our patient’s case the presentation was acute, with rapid deterioration in neurological status. Initially the head CT scan showed bilateral old infarcts, suggestive of cardioembolic source. However, the new infarcts on repeat imaging were extensive and confined to the left hemisphere.

Clinical presentation for patients with thromboembolic complications may vary from being asymptomatic to dyspnea, cardiogenic shock, cerebral or peripheral embolic episodes. Loss of prosthetic valve click on clinical examination may be suggestive of prosthetic valve thrombosis. Transthoracic echocardiogram is the initial diagnostic tool and provides information about valvular morphology and function. Transesophageal echocardiography is often required to provide more accurate images and to distinguish between pannus and thrombus. A thrombus has usually an echodensity similar to the myocardium while pannus appears more hyperechoic[15]. Fluoroscopy may also be useful for assessment of valve function by showing restriction of valve leaflet movements in case of prosthetic valve thrombosis[16].

Treatment options include thrombolytic therapy, surgical thrombectomy or surgical replacement of the valve. Depending on the clinical status of the patient, surgical mortality can be as high as 69%. Thrombolytic therapy can also result in thromboembolic complications or hemorrhage[17]. Cáceres-Lóriga et al[2], have recommended that in all patients with confirmed right-sided prosthetic valve thrombosis initial treatment should be intravenous thrombolytic therapy, with serial echocardiograms. Thrombolytic therapy may be repeated if required and urgent surgical consultation for valve-replacement should be sought for failure of thrombus resolution. Medically stable patients can be managed with thrombolytic therapy and then continued anticoagulation.

Thrombosis of mechanical prosthetic cardiac valves is associated with high morbidity and mortality and treatment options available can also be associated with serious complications. This mandates the need for high clinical suspicion for thrombosis when a patient with a prosthetic cardiac valve presents with shortness of breath or with an embolic event.

Rene Robinson-Armatta for providing assistance with acquiring echocardiographic images.

Acute onset of right sided weakness and altered mental status.

Unresponsive patient in atrial fibrillation with right arm and leg paralysis.

Computed tomography (CT) scan of the head done to diagnose acute cerebrovascular accident and transthoracic echocardiogram done to evaluate for cardiac source of emboli.

Laboratory tests showed elevated white cell count with mild anemia and subtherapeutic international normalized ratio (INR).

Initial CT scan of the head showed old bilateral infarcts and repeat CT head showed left frontal, parietal, insular and temporal lobes and involving the left basal ganglia, with associated petechial hemorrhages.

Patient started on broad spectrum antibiotics for possible sepsis and initially started on intravenous heparin for subtherapeutic INR, but heparin discontinued due to subsequent intracerebral petechial hemorrhages.

The authors have included references from the study by Cannegieter et al about thrombosis and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical cardiac valves. The authors have also reviewed and included in manuscript the manuscript by Barbetseas et al which explains how to differentiate thrombus from pannus.

Polymorphisms: Occurrence of more than one form; Thrombogenic: Promoting thrombosis.

Maintaining therapeutic INR in patients with mechanical prosthetic cardiac valves is critical and high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis of complications associated with prosthetic valves.

The authors present a clinical note of a 72-year-old female patient suffering from an ischemic stroke of embolic etiology secondary to thrombosis of mechanical prosthetic cardiac valve. This information is interesting from a clinical point of view.

P- Reviewer: Amiri M, Arboix A S- Editor: Tian YL L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Edmunds LH, Clark RE, Cohn LH, Grunkemeier GL, Miller DC, Weisel RD. Guidelines for reporting morbidity and mortality after cardiac valvular operations. Ad Hoc Liaison Committee for Standardizing Definitions of Prosthetic Heart Valve Morbidity of The American Association for Thoracic Surgery and The Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1996;112:708-711. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 238] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 242] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cáceres-Lóriga FM, Pérez-López H, Santos-Gracia J, Morlans-Hernandez K. Prosthetic heart valve thrombosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Int J Cardiol. 2006;110:1-6. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Singer DE, Chang Y, Fang MC, Borowsky LH, Pomernacki NK, Udaltsova N, Go AS. The net clinical benefit of warfarin anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:297-305. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 493] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 492] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Garcia D, Libby E, Crowther MA. The new oral anticoagulants. Blood. 2010;115:15-20. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 208] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 218] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Hirsh J. Oral anticoagulant drugs. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1865-1875. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 334] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Briët E. Thromboembolic and bleeding complications in patients with mechanical heart valve prostheses. Circulation. 1994;89:635-641. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 699] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 628] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Lengyel M. Management of prosthetic valve thrombosis. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13:329-334. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Taljaard JJ, Doubell AF. Prosthetic valve obstruction at Tygerberg Hospital between January 1991 and February 2001. Cardiovasc J S Afr. 1991;14:182-188. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Piper C, Horstkotte D. State of the art anticoagulation management. J Heart Valve Dis. 2004;13 Suppl 1:S76-S80. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Aoyagi S, Fukunaga S, Suzuki S, Nishi Y, Oryoji A, Kosuga K. Obstruction of mechanical valve prostheses: clinical diagnosis and surgical or nonsurgical treatment. Surg Today. 1996;26:400-406. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Deviri E, Sareli P, Wisenbaugh T, Cronje SL. Obstruction of mechanical heart valve prostheses: clinical aspects and surgical management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17:646-650. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 220] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 234] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mehra S, Prodduturvar P, Marcu CB, Chelu MG. Use of Novel Oral Anticoagulants Postcardioversion in Atrial Fibrillation: A Safety Review. British J Medicine and Medical Research. 2015;7:718-722. [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Eikelboom JW, Connolly SJ, Brueckmann M, Granger CB, Kappetein AP, Mack MJ, Blatchford J, Devenny K, Friedman J, Guiver K. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with mechanical heart valves. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1206-1214. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 978] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 931] [Article Influence: 84.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kolominsky-Rabas PL, Weber M, Gefeller O, Neundoerfer B, Heuschmann PU. Epidemiology of ischemic stroke subtypes according to TOAST criteria: incidence, recurrence, and long-term survival in ischemic stroke subtypes: a population-based study. Stroke. 2001;32:2735-2740. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 774] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 802] [Article Influence: 34.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | 15 Barbetseas J, Nagueh SF, Pitsavos C, Toutouzas PK, Quiñones MA, Zoghbi WA. Differentiating thrombus from pannus formation in obstructed mechanical prosthetic valves: an evaluation of clinical, transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiographic parameters. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32:1410-1417. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Montorsi P, Cavoretto D, Alimento M, Muratori M, Pepi M. Prosthetic mitral valve thrombosis: can fluoroscopy predict the efficacy of thrombolytic treatment? Circulation. 2003;108 Suppl 1:II79-II84. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Martinell J, Jiménez A, Rábago G, Artiz V, Fraile J, Farré J. Mechanical cardiac valve thrombosis. Is thrombectomy justified? Circulation. 1991;84:III70-III75. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |