Published online May 16, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4509

Peer-review started: July 16, 2021

First decision: October 18, 2021

Revised: October 30, 2021

Accepted: March 25, 2022

Article in press: March 25, 2022

Published online: May 16, 2022

The association of Sjögren's syndrome (SS) and lymphoma is similar. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) or extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma was the most common lymphomatous histology in SS patients. MALT in SS patients is frequently located in the parotid gland, while MALT lymphoma of the skin with SS is an exceedingly rare entity that needs to be recognized.

A 60-year-old woman presented with a 3-year history of progressive dry mouth associated with a 1-year history of enlarging cutaneous nodules. Physical examination revealed two hard subcutaneous nodules on her right lower leg. The results of Schirmer’s test were positive, despite the absence of dry eyes. Labial salivary gland biopsy revealed lymphocytic infiltration and chronic inflammation with a focus score of 2. The patient was diagnosed with SS. She underwent resection of one cutaneous nodule, and histopathological analysis identified the nodule as MALT lymphoma. Her dry mouth symptoms improved, and the nodules decreased after 6 mo of treatment with hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chemotherapy (thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, and dexamethasone).

Lymphoma is a severe complication of SS, shown by the reported unique case of cutaneous MALT lymphoma with SS.

Core Tip: Lymphoma is a severe complication of Sjögren's syndrome (SS) and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma is the most common type. We report a rare case of cutaneous MALT lymphoma with SS. A literature review was performed to provide information on the condition’s clinical manifestations and associated extensive sites. Our case highlights that the skin is rarely involved aside from the parotid gland, orbital adnexa, lung, thyroid, and stomach. Patients may have no symptoms; thus, regular physical assessments are required.

- Citation: Liu Y, Zhu J, Huang YH, Zhang QR, Zhao LL, Yu RH. Cutaneous mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma complicating Sjögren's syndrome: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(14): 4509-4518

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i14/4509.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i14.4509

Sjögren's syndrome (SS) is a chronic systemic autoimmune disease characterized by lymphocytic infiltration of exocrine glands, compromising lacrimal and salivary gland secretions. Lymphoma is a severe complication of SS. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, also known as extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma (EMZL), is the most common histologic type in SS patients[1]. The parotid gland is the most frequent location; however, it has also been detected in the lung, thyroid, and stomach[2-4]. To our knowledge, MALT lymphomas involving the skin have not been reported in patients with SS.

A 60-year-old woman was admitted to our rheumatology department due to progressive dry mouth and enlarging cutaneous nodules.

Over the past 3 years, the patient has experienced mild-to-moderate dry mouth without dry eyes or any special medicine. A painless cutaneous nodule was found in her right lower leg 1 year previously, and the nodule had gradually enlarged within the past 6 mo. The nodule was resected, and pathological examination showed a possible lymphoproliferative disease. In the following months, her symptoms of dry mouth were aggravated, and nodules in the right lower leg relapsed with an increase in number. The patient was then referred to our hospital for further examination. She did not have arthralgia, parotid gland swelling, fatigue, decreased appetite, or unintentional weight loss.

The patient’s past medical history was unremarkable.

The patient’s personal and family history was also unremarkable.

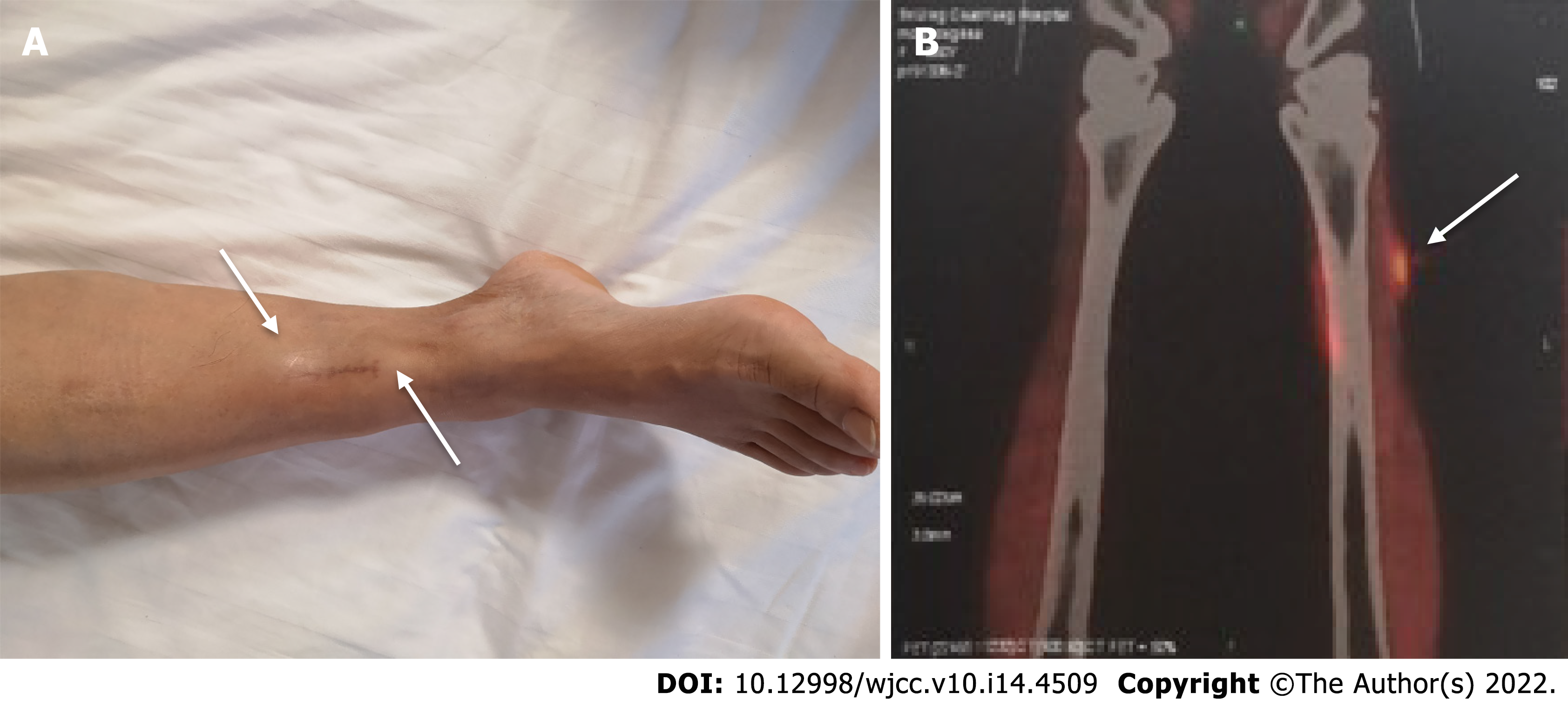

Physical examination only showed two hard subcutaneous nodules on her right lower leg (Figure 1A).

On admission, laboratory tests showed normal blood cell count, and routine urine, creatinine, coagulation markers, cardiac enzymes, complement, and inflammatory biomarker levels. Elevated alkaline phosphatase (203 U/L, reference range, 35–135 U/L) and gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (423 U/L, reference range, 7–45 U/L) were noted. Serum tumor markers (CA125, CA153, CA19-9, AFP, CEA, and CYFRA21-1) and viral serology (HIV, HBV, and HCV) was negative. Protein and immunofixation electrophoreses revealed no evidence of serum monoclonal gammopathy or Bence-Jones proteinuria. Serum-free light-chain levels were normal. Anti-nuclear antibody was positive (1 : 640 centromere pattern), while no Sjögren's syndrome type A antigen (SSA)/Ro or type B (SSB)/La antibodies were detected. The bone marrow aspirate and biopsy results were normal.

High-resolution chest computed tomography (CT) did not show any signs of interstitial pneumonitis or mediastinal lymphadenopathy. Positron emission tomography CT demonstrated increased fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in the right anterolateral tibialis anterior, and several nodular shadows (Figure 1B). There were no signs of invasion or spread to the surrounding structures or organs.

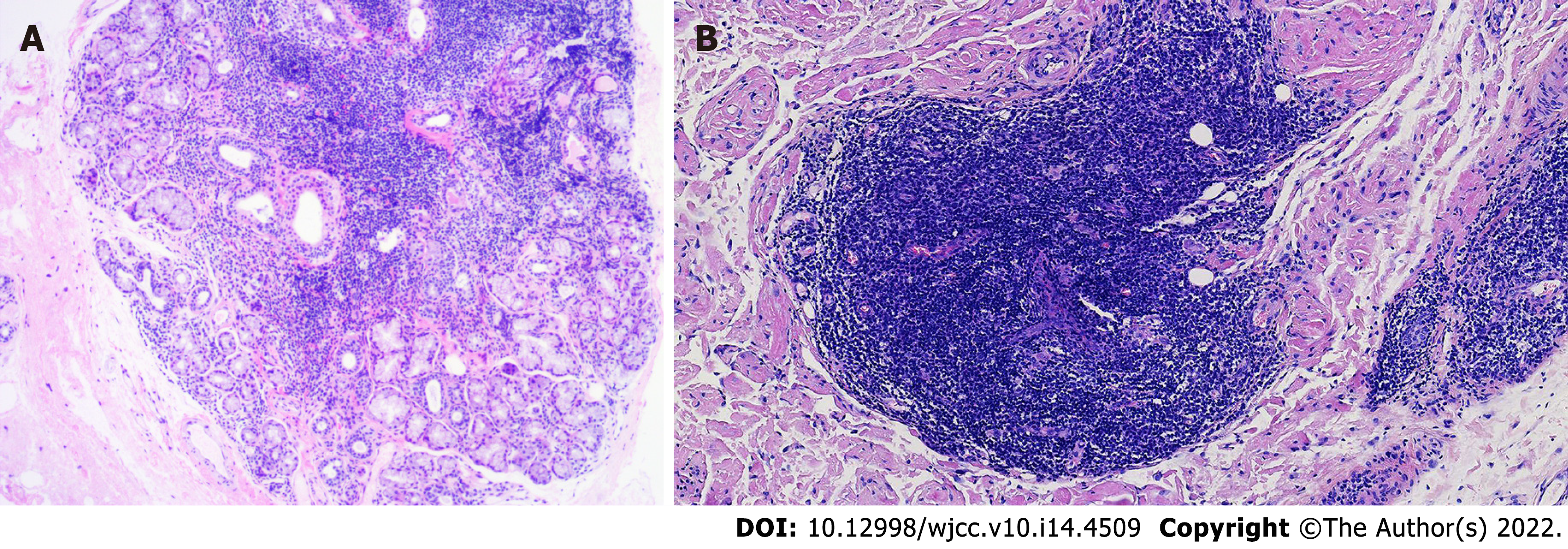

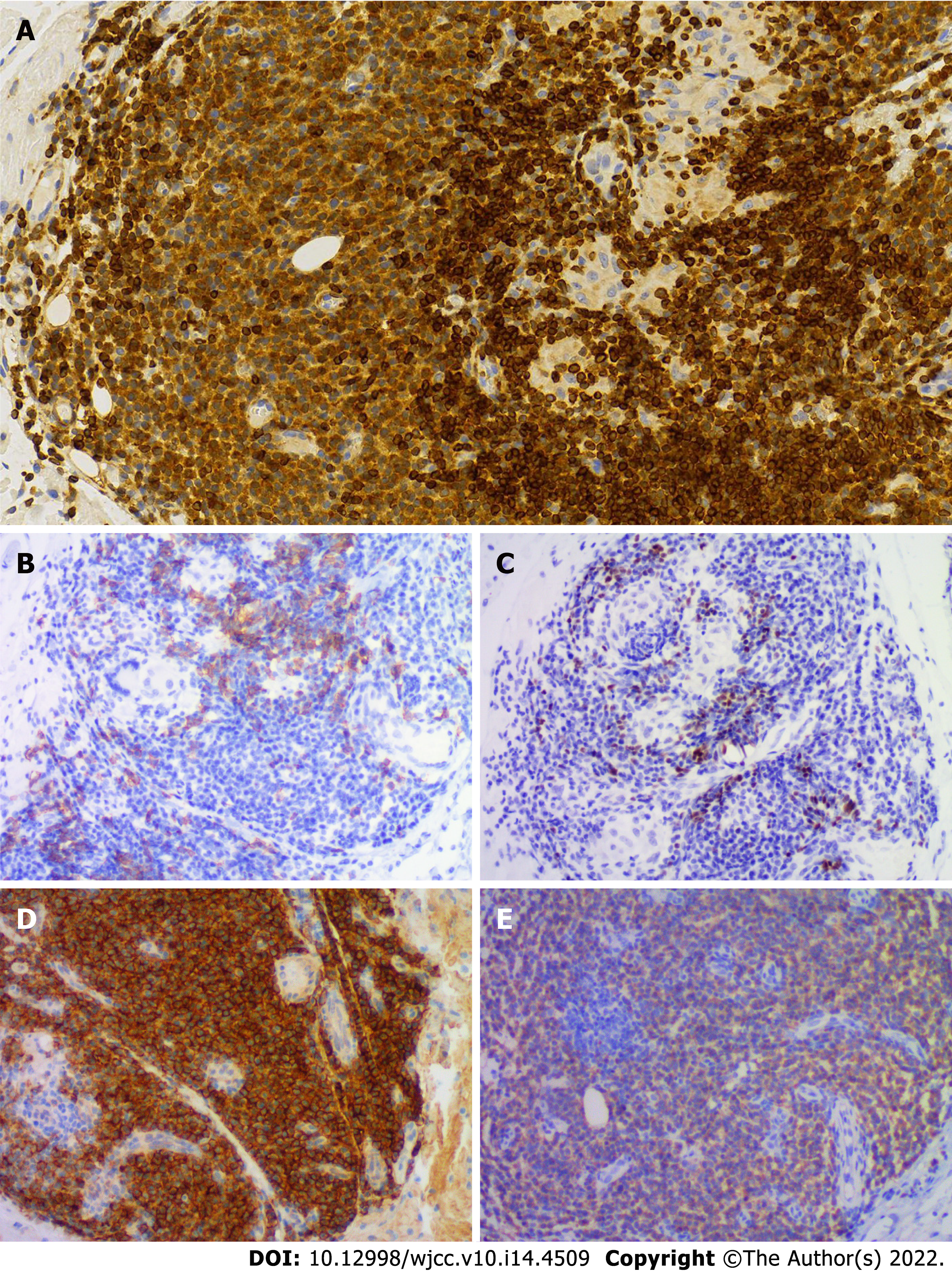

The Schirmer’s test showed positive results, despite the absence of dry eyes. Labial salivary gland biopsy revealed lymphocytic infiltration and chronic inflammation with a focus score (FS) of 2 (Figure 2A). Repeat cutaneous biopsy showed a possible neoplastic infiltration composed of small lymphocytes occupying the marginal zone and plasma cells associated with hyperplastic B-cell follicles at the periphery of the follicle zone (Figure 2B). She was Bcl2- (Figure 3A), CD5-, CD20- (Figure 3B), and PAX5-positive (Figure 3C), and CD3-, CD10-, and Bcl6-negative. Plasma cells were highlighted by CD138 (Figure 3D) and showed clear kappa-light chain restriction (Figure 3E). Immunoglobulin gene rearrangements were positive for IgK (Vk-Jk, Vk-Kde+INTR-Kde) and probably positive for IgH (FR1-JH, FR2-JH).

The patient presented with symptoms of oral dryness for more than 3 mo, without a history of head and neck radiation treatment, active hepatitis C infection, AIDS, sarcoidosis, amyloidosis, graft-versus-host disease and IgG4-related disease, and was diagnosed with SS according to the 2016 American College of Rheumatology-European League Against Rheumatism (ACR-EULAR) classification criteria for SS[5]. Primary biliary cholangitis was suspected based on elevated alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, and positive anticentromere antibody. Based on the histopathological findings, a MALT cutaneous EMZL was diagnosed. The final diagnosis was cutaneous MALT lymphoma complicating SS.

The patient was started on 400 mg of hydroxychloroquine sulfate tablets and 500 mg of ursodeoxycholic acid daily. She was then referred to a hematologist for chemotherapy with 100 mg of thalidomide daily, 50 mg of cyclophosphamide on days 1–14, and 20 mg of dexamethasone on days 1–4, 9–12, 17–20, and 25–28 in a 28-d cycle.

At the last follow-up (after 6 mo), her symptoms of dry mouth had improved and liver function had normalized. The nodules decreased, and there was no evidence of recurrent lymphoma.

We searched for articles from April 2010 to April 2020 for “Sjögren's syndrome (MeSH Terms)” AND “MALT lymphoma (MeSH Terms)” in PubMed. The language was restricted to English. Review articles, articles not reporting on SS with MALT lymphoma, articles about secondary SS, articles missing important information, and articles not found in full text were excluded. In total, 87 articles were identified by the search criteria. Fourteen non-English articles, 11 review articles, 29 not reporting on SS with MALT lymphoma, 3 about secondary SS, and 4 without full texts were excluded from the review. Twenty-six articles (including one prospective study, four retrospective studies, several case reports, and case series) with comprehensive clinical and laboratory data from 142 patients were included and analyzed in detail, including race, age, sex, symptoms, and location of MALT lymphoma[2-4,6-28]. All patients were clinically diagnosed with SS and fulfilled the ACR-EULAR classification criteria[5] or the American-European Consensus Group criteria[29]. The median age at SS diagnosis was 45 years (range, 29–73 years). The mean lymphoma onset age was 54 years (range, 35–74 years). All patients were diagnosed with MALT lymphoma after or simultaneously with SS. Among the 142 patients, 133 were female, 45 (34 missing data) presented with symptoms of dry eyes and xerostomia, 26 (46 missing data) complained of constitutional symptoms (fatigue, decreased appetite, or weight loss), 51 (40 missing data) had parotid gland swelling, while cryoglobulinemia or cryoglobulinemic vasculitis occurred in 10 (65 missing data), 37 had monoclonal gammopathy, 100 (29 missing data) showed Anti-Ro/SSA antibodies, 41 (35 missing data) had anti-La/SSB antibodies, 87 (40 missing data) were rheumatoid factor (RF)-positive, and 31 (65 missing data) had low C4 Levels. Lymphocytic infiltration focus (FS ≥ 1), which is typical for SS, was reported in 36 (87.8%) patients. In addition, 101 (71.1%) patients did not undergo baseline salivary gland biopsy, and 5 (12.2%) patients had negative FS. MALT lymphoma was found in the parotid gland (77.5%), lung (14.8%), thymus (5.6%), lymph nodes (4.2%), bone marrow (3.5%), submandibular glands (2.1%), lacrimal gland (1.4%), and other organs, such as the stomach, breast, tongue, spleen, liver, kidney, and mouth. The detailed patient characteristics are shown in Table 1. The clinical and laboratory data of the 26 cases or case series are summarized in Table 2.

| Patients characteristics | SS with MALT lymphoma (n = 142) |

| Age of SS diagnosis, mean year | 45 |

| Age of lymphoma onset, mean year | 54 |

| Female, n (%) | 133/142 (93.7) |

| Dry eye, n (%) | 45/108 (41.7) |

| Dry mouth, n (%) | 45/108 (41.7) |

| Parotid gland swelling, n (%) | 51/102 (50.0) |

| Fatigue, decreased appetite, or weight loss, n (%) | 26/96 (27.1) |

| Cryoglobulinemia or cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, n (%) | 10/77 (13.0) |

| ANA positive, n (%) | 104/113 (92.0) |

| Anti-Ro/SSA positive, n (%) | 100/113 (88.5) |

| Anti-La/SSB positive, n (%) | 41/107 (38.3) |

| Monoclonal gammopathy, n (%) | 37/82 (45.1) |

| RF positive, n (%) | 87/102 (85.3) |

| Low C4, n (%) | 31/77 (40.3) |

| Positive SG biopsy, FS ≥ 1, n (%) | 36/41 (87.8) |

| Lymphoma location Parotid gland, n (%) | 110 (77.5) |

| Lung, n (%) | 21 (14.8) |

| Thymus, n (%) | 8 (5.6) |

| Lymph nodes, n (%) | 6 (4.2) |

| Bone marrow, n (%) | 5 (3.5) |

| Submandibular glands, n (%) | 3 (2.1) |

| Lacrimal gland, n (%) | 2 (1.4) |

| Other sites, n (%) (stomach, breast, tongue, spleen, liver, kidney, mouth, lip) | 9 (6.3) |

| Ref. | n | Age of SS diagnosis | Age of lymphoma onset | Sex | Sicca symptom | Risk factor | Anti-SSA/SSB | Lymphoma location | Stage (Ann Arbor) | Treatment | Prognosis |

| Xu et al[3] | 4 | NA | 42 | M | — | PGS | SSA/SSB | Parotid gland, thymus | IVA | Surgery | Improved |

| NA | 49 | F | — | PGS, Monoclonal gammopathy, RF | SSA/SSB | Parotid gland, thymus | IVA | Surgery | Improved | ||

| NA | 49 | F | — | Monoclonal gammopathy | SSA/SSB | Thymus | IVA | Surgery | Improved | ||

| NA | 38 | F | — | RF | SSA/SSB | Thymus | IA | Surgery | Improved | ||

| Belfeki et al[6] | 1 | 60 | 65 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | PGS, Monoclonal gammopathy, low C3, low C4 | SSA | Breast | NA | NA | NA |

| Xian et al[7] | 1 | NA | 45 | F | NA | NA | NA | Lung | NA | Chemotherapy | Deceased |

| Arai et al[12] | 1 | NA | 66 | F | NA | RF | SSA | Thymus | NA | Surgery | Improved |

| Momoi et al[13] | 1 | 52 | 58 | F | NA | RF | SSA | Thymus | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy | Improved |

| Yoshida et al[14] | 1 | 32 | NA | F | NA | Monoclonal gammopathy | SSA | Thymus | NA | Surgery, chemotherapy | Improved |

| Hsu et al[15] | 1 | NA | 54 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | NA | SSA | Mouth | IE | Surgery | Improved |

| De Vita et al[16] | 1 | 41 | 46 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | PGS, cryoglobulins,RF, low C4 | SSA/SSB | Parotid gland | IE | Belimumab, RTX | Improved |

| Kobayashi et al[17] | 1 | 31 | 39 | F | Dry eye | NA | SSA/SSB | Lung | I | GS | NA |

| Taylor et al[18] | 1 | NA | 67 | F | NA | NA | NA | Lung | NA | Surgery | NA |

| Baqir et al[19] | 3 | NA | 74 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | NA | SSA/SSB | Lung | NA | NA | NA |

| NA | 48 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | NA | SSA/SSB | Lung | NA | NA | NA | ||

| NA | 53 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | NA | SSA/SSB | Lung | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Kluka et al[20] | 1 | 33 | 53 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | Monoclonal gammopathy | SSA/SSB | Lung | I | HCQ, GS | NA |

| Keszler et al[21] | 1 | 60 | 62 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | RF | — | Minor labial salivary gland | I | — | Improved |

| Watanabe et al[22] | 1 | 29 | 49 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | NA | SSA/SSB | Lung | IV | Chemotherapy | Improved |

| De Vita et al[23] | 1 | 45 | 51 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | PGS, cryoglobulins, RF, low C4 | SSA/SSB | Parotid gland | IE | RTX | Improved |

| Covelli et al[25] | 2 | 32 | 35 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | PGS, RF, low C4 | SSA | Parotid gland | NA | RTX | NA |

| 42 | 44 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | Monoclonal gammopathy, RF | SSA/SSB | Lung | NA | GS, RTX | NA | ||

| Ornetti et al[26] | 1 | 73 | 73 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | PGS | SSA | Parotid gland | NA | RTX, chemotherapy | Improved |

| Movahed et al[27] | 1 | 36 | 41 | F | Dry mouth | PGS | NA | Submandibular glands | III | — | Improved |

| Zenone et al[28] | 2 | 55 | 56 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | PGS, cryoglobulins, RF | — | Parotid gland | NA | RTX, chemotherapy, radiotherapy | Progressive |

| 31 | 42 | F | Dry eye, dry mouth | PGS, cryoglobulins, Monoclonal gammopathy | SSA/SSB | Parotid gland | NA | HCQ, RTX | Improved |

The recently reported frequency of lymphoma complicated with SS in the Asian and East Central European populations are 2.7%–9.8%[30] and 2%[31], respectively. It is estimated that the risk of lymphoma in patients with SS is about nine times higher than that in the general population[32]. MALT is the most common lymphomatous histology in SS patients[1], but nodal marginal zone lymphoma and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma have also been identified[30,32,33]. As MALT lymphoma in patients with SS is rare, its incidence is unclear. The most common sites of MALT lymphomas are the stomach, eye/adnexa, and spleen[34-36]. However, in SS patients, the parotid gland is the most frequent location of MALT lymphoma, as demonstrated by our literature review. It is reported that SS patients have a 1000-fold increased risk of MALT lymphoma of the parotid gland[37]. Other sites of MALT lymphoma in SS, such as the lung[4,7], thymus[12,13], submandibular glands[4,27], breast[6], liver[4], and stomach[4] can also be involved. However, cutaneous MALT lymphomas are exceedingly rare in SS. We confirmed our case as cutaneous MALT lymphoma according to the histopathology and immunoglobulin gene rearrangement findings in the setting of SS. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of cutaneous MALT associated with SS.

SS is characterized by polyclonal lymphocytic infiltration and chronic inflammation of the exocrine glands. In most patients, lymphoproliferation remains confined to the glandular tissue and does not undergo malignant transformation, indicating that the pathological transition to MALT lymphoma is characterized by the expansion of the centrocyte-like B-cell population and the infiltration of B cells aberrantly expressing CD5 and CD43. The precise pathogenic mechanisms of the transition from SS to lymphoma are currently being studied[38]. Differentiating benign lymphoid proliferation and malignant MALT lymphoma can be difficult and requires the integration of morphological, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric analyses of appropriate biopsy material[39-41]. MALT lymphoma at many sites (including salivary glands) is associated with the presence of lymphoepithelial islands, which become infiltrated by aggregates of neoplastic lymphoid cells. In addition, a diffuse dense infiltrate of CD20 positive cells and destruction of the normal parenchyma of the glands are features supporting lymphoma. As for immunophenotype, the neoplastic cells were positive for CD19 and CD20 and negative for CD10, Bcl-6, and cyclin D1[42]. Immunoglobulin light-chain restriction may also be demonstrated, especially in plasma cells. Molecular diagnostic analysis consisting of PCR-based analysis of immunoglobulin gene rearrangements can also be very helpful in distinguishing EMZL from reactive proliferation. As described in our patient, MALT lymphoma was diagnosed by morphology, immunophenotype, and immunoglobulin gene rearrangements of cutaneous biopsy.

Several studies have recently focused on biomarkers for developing lymphoma during the course of SS. Characteristics, such as persistent salivary gland swelling, low C4, leukopenia, cryoglobulinemia and/or cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, monoclonal gammopathy, and positive RF are considered risk factors[43-45]. De Vita et al[4] reported that salivary gland swelling and/or cryoglobulinemia at baseline were more commonly seen in SS patients evolving into lymphoma than in SS controls, and the risk of lymphoma was increased in SS patients with salivary gland swelling and/or cryoglobulinemia. According to the reviewed literature, parotid gland swelling, positive RF, monoclonal gammopathy, and low C4 are more frequent (40%–85%) in SS patients with MALT lymphoma, while cryoglobulinemia and cryoglobulinemic vasculitis are less frequent (13%). However, none of these parameters was screened in our patient. This may have been because the MALT lymphoma involved skin rather than the parotid gland. Further prospective studies are required. Constant monitoring of lymphoma is necessary in SS patients.

Labial salivary gland biopsy is a diagnostic test for SS and aids in the detection of lymphoma. Cases of MALT lymphoma with SS in the labial salivary glands have rarely been reported. Keszler et al[21] reported a case of a 60-year-old female patient with SS who developed MALT lymphoma in the labial salivary glands during a 2-year time interval. In our case, labial salivary gland biopsy revealed lymphocytic infiltration and chronic inflammation (FS = 2) and showed no evidence of neoplastic cells. An FS ≥ 3 was suggested as a predictive factor for lymphoma development[46]. However, negative FS (FS < 1) was present in five patients with MALT lymphoma in our literature review. Consistently, Haacke et al[10] showed that FS did not differ between SS patients with parotid MALT lymphoma and SS controls who were lymphoma free. The percentage of biopsies with FS ≥ 3 was even higher in the control group (36% vs 27%). Therefore, the FS of labial gland biopsies is not a predictive factor for SS-associated MALT lymphomas.

Pollard et al[24] reported the treatment of MALT lymphoma in SS, including watchful waiting, surgery, radiotherapy, surgery combined with radiotherapy, rituximab monotherapy, and rituximab combined with chemotherapy, and found that an initially high SS disease activity likely constitutes an adverse prognostic factor for the progression of lymphoma and/or SS. Such patients may require treatment for both conditions. In SS patients with localized asymptomatic MALT lymphoma and low SS disease activity, watchful waiting seems justified. In our case, the patient with low SS disease activity and localized asymptomatic MALT lymphoma received positive chemotherapy at her request.

Prompt recognition of the possible cutaneous lymphoproliferative complications of SS is essential to avoid delayed diagnosis or treatment. Further multicenter prospective studies are necessary to better understand the pathogenesis, treatment, and outcomes of MALT lymphoma in SS patients.

We thank the participant of this study and all the staff who participated the clinical management of the patient.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Rheumatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Vissink A, Netherlands S-Editor: Xing YX L-Editor: A P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Brito-Zerón P, Kostov B, Fraile G, Caravia-Durán D, Maure B, Rascón FJ, Zamora M, Casanovas A, Lopez-Dupla M, Ripoll M, Pinilla B, Fonseca E, Akasbi M, de la Red G, Duarte-Millán MA, Fanlo P, Guisado-Vasco P, Pérez-Alvarez R, Chamorro AJ, Morcillo C, Jiménez-Heredia I, Sánchez-Berná I, López-Guillermo A, Ramos-Casals M; SS Study Group GEAS-SEMI. Characterization and risk estimate of cancer in patients with primary Sjögren syndrome. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:90. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Yachoui R, Leon C, Sitwala K, Kreidy M. Pulmonary MALT Lymphoma in Patients with Sjögren's Syndrome. Clin Med Res. 2017;15:6-12. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | Xu DM, Wang L, Zhu HY, Liang JH, Li JY, Xu W. [Primary thymic mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma: 7 clinical cases report and a review of the literature]. Zhonghua Xue Ye Xue Za Zhi. 2020;41:54-58. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | De Vita S, Gandolfo S, Zandonella Callegher S, Zabotti A, Quartuccio L. The evaluation of disease activity in Sjögren's syndrome based on the degree of MALT involvement: glandular swelling and cryoglobulinaemia compared to ESSDAI in a cohort study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2018;36 Suppl 112:150-156. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 5. | Shiboski CH, Shiboski SC, Seror R, Criswell LA, Labetoulle M, Lietman TM, Rasmussen A, Scofield H, Vitali C, Bowman SJ, Mariette X; International Sjögren's Syndrome Criteria Working Group. 2016 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for primary Sjögren's syndrome: A consensus and data-driven methodology involving three international patient cohorts. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:9-16. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 6. | Belfeki N, Bellefquih S, Bourgarit A. Breast MALT lymphoma and AL amyloidosis complicating Sjögren's syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Xian JZ, Cherian SV, Idowu M, Chen L, Estrada-Y-Martin RM. A 45-Year-Old Woman With Multiple Pulmonary Nodules and Sjögren Syndrome. Chest. 2019;155:e51-e54. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 8. | Zampeli E, Kalogirou EM, Piperi E, Mavragani CP, Moutsopoulos HM. Tongue Atrophy in Sjögren Syndrome Patients with Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma: Autoimmune Epithelitis beyond the Epithelial Cells of Salivary Glands? J Rheumatol. 2018;45:1565-1571. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 9. | Demaria L, Henry J, Seror R, Frenzel L, Hermine O, Mariette X, Nocturne G. Rituximab-Bendamustine (R-Benda) in MALT lymphoma complicating primary Sjögren syndrome (pSS). Br J Haematol. 2019;184:472-475. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Haacke EA, van der Vegt B, Vissink A, Spijkervet FKL, Bootsma H, Kroese FGM. Germinal centres in diagnostic labial gland biopsies of patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome are not predictive for parotid MALT lymphoma development. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76:1781-1784. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 11. | Baldini C, Santini E, Rossi C, Donati V, Solini A. The P2X7 receptor-NLRP3 inflammasome complex predicts the development of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in Sjogren's syndrome: a prospective, observational, single-centre study. J Intern Med. 2017;282:175-186. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 12. | Arai H, Tajiri M, Kaneko S, Kushida Y, Ando K, Tachibana T, Umeda S, Okudela K, Komatsu S, Masuda M. Two surgical cases of thymic MALT lymphoma associated with multiple lung cysts: possible association with Sjögren's syndrome. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;65:229-234. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Momoi A, Nagai K, Isahai N, Sakai T, Ohshima K, Aoki S. Thymic Extranodal Marginal Zone Lymphoma of Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue with 8q24 Abnormality. Intern Med. 2016;55:799-803. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Yoshida A, Watanabe M, Ohmine K, Kawashima H. Central retinal vein occlusion caused by hyperviscosity syndrome in a young patient with Sjögren's syndrome and MALT lymphoma. Int Ophthalmol. 2015;35:429-432. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 15. | Hsu YT, Chiu PH, Chen YK, Chiang RP. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma on the mouth floor presenting with Sjögren's syndrome and giant cell tumor of spinal tendon. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2014;30:316-318. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 16. | De Vita S, Quartuccio L, Salvin S, Picco L, Scott CA, Rupolo M, Fabris M. Sequential therapy with belimumab followed by rituximab in Sjögren's syndrome associated with B-cell lymphoproliferation and overexpression of BAFF: evidence for long-term efficacy. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32:490-494. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 17. | Kobayashi T, Muro Y, Sugiura K, Akiyama M. Pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in Sjögren's syndrome without interstitial pneumonia. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:780-782. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 18. | Taylor WS, Vaughan P, Trotter S, Rajesh PB. A rare association of pulmonary carcinoid, lymphoma, and sjögren syndrome. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:1086-1087. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 19. | Baqir M, Kluka EM, Aubry M-C, Hartman TE, Yi ES, Bauer PR, Ryu JH. Amyloid-associated cystic lung disease in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Respir Med. 2013;107:616-621. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 20. | Kluka EM, Bauer PR, Aubry MC, Ryu JH. Enlarging lung nodules and cysts in a 53-year-old woman with primary Sjögren syndrome. Chest. 2013;143:258-261. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 21. | Keszler A, Adler LI, Gandolfo MS, Masquijo Bisio PA, Smith AC, Vollenweider CF, Heidenreich AM, de Stefano G, Kambo MV, Cox DP, Narbaitz M, Lanfranchi HE. MALT lymphoma in labial salivary gland biopsy from Sjögren syndrome: importance of follow-up in early detection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2013;115:e28-e33. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 22. | Watanabe Y, Koyama S, Miwa C, Okuda S, Kanai Y, Tetsuka K, Nokubi M, Dobashi Y, Kawabata Y, Kanda Y, Endo S. Pulmonary mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma in Sjögren's syndrome showing only the LIP pattern radiologically. Intern Med. 2012;51:491-495. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 23. | De Vita S, Quartuccio L, Salvin S, Corazza L, Zabotti A, Fabris M. Cryoglobulinaemia related to Sjogren's syndrome or HCV infection: differences based on the pattern of bone marrow involvement, lymphoma evolution and laboratory tests after parotidectomy. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:627-633. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Pollard RP, Pijpe J, Bootsma H, Spijkervet FK, Kluin PM, Roodenburg JL, Kallenberg CG, Vissink A, van Imhoff GW. Treatment of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma in Sjogren's syndrome: a retrospective clinical study. J Rheumatol. 2011;38:2198-2208. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 25. | Covelli M, Lanciano E, Tartaglia P, Grattagliano V, Angelelli G, Atzeni F, Sarzi-Puttini P, Lapadula G. Rituximab treatment for Sjogren syndrome-associated non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: case series. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:3281-3284. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 26. | Ornetti P, Vinit J. Images in clinical medicine. Sjögren's syndrome and MALT lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:e41. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 27. | Movahed R, Weiss A, Velez I, Dym H. Submandibular gland MALT lymphoma associated with Sjögren's syndrome: case report. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;69:2924-2929. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 28. | Zenone T. Parotid gland non-Hodgkin lymphoma in primary Sjögren syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32:1387-1390. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 29. | Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos HM, Alexander EL, Carsons SE, Daniels TE, Fox PC, Fox RI, Kassan SS, Pillemer SR, Talal N, Weisman MH; European Study Group on Classification Criteria for Sjögren's Syndrome. Classification criteria for Sjögren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:554-558. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 30. | Chiu YH, Chung CH, Lin KT, Lin CS, Chen JH, Chen HC, Huang RY, Wu CT, Liu FC, Chien WC. Predictable biomarkers of developing lymphoma in patients with Sjögren syndrome: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:50098-50108. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 31. | Sebastian A, Madej M, Sebastian M, Butrym A, Woytala P, Hałoń A, Wiland P. Prevalence and clinical presentation of lymphoproliferative disorder in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome. Rheumatol Int. 2020;40:399-404. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 32. | Johnsen SJ, Brun JG, Gøransson LG, Småstuen MC, Johannesen TB, Haldorsen K, Harboe E, Jonsson R, Meyer PA, Omdal R. Risk of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a population-based study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:816-821. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 33. | Voulgarelis M, Ziakas PD, Papageorgiou A, Baimpa E, Tzioufas AG, Moutsopoulos HM. Prognosis and outcome of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in primary Sjögren syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore). 2012;91:1-9. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 34. | Khalil MO, Morton LM, Devesa SS, Check DP, Curtis RE, Weisenburger DD, Dores GM. Incidence of marginal zone lymphoma in the United States, 2001-2009 with a focus on primary anatomic site. Br J Haematol. 2014;165:67-77. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 35. | Rosado MF, Byrne GE Jr, Ding F, Fields KA, Ruiz P, Dubovy SR, Walker GR, Markoe A, Lossos IS. Ocular adnexal lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of a large cohort of patients with no evidence for an association with Chlamydia psittaci. Blood. 2006;107:467-472. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 36. | Zucca E, Conconi A, Pedrinis E, Cortelazzo S, Motta T, Gospodarowicz MK, Patterson BJ, Ferreri AJ, Ponzoni M, Devizzi L, Giardini R, Pinotti G, Capella C, Zinzani PL, Pileri S, López-Guillermo A, Campo E, Ambrosetti A, Baldini L, Cavalli F; International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group. Nongastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. Blood. 2003;101:2489-2495. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 37. | Ekström Smedby K, Vajdic CM, Falster M, Engels EA, Martínez-Maza O, Turner J, Hjalgrim H, Vineis P, Seniori Costantini A, Bracci PM, Holly EA, Willett E, Spinelli JJ, La Vecchia C, Zheng T, Becker N, De Sanjosé S, Chiu BC, Dal Maso L, Cocco P, Maynadié M, Foretova L, Staines A, Brennan P, Davis S, Severson R, Cerhan JR, Breen EC, Birmann B, Grulich AE, Cozen W. Autoimmune disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: a pooled analysis within the InterLymph Consortium. Blood. 2008;111:4029-4038. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 38. | Nocturne G, Mariette X. Sjögren Syndrome-associated lymphomas: an update on pathogenesis and management. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:317-327. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 39. | Carbone A, Gloghini A, Ferlito A. Pathological features of lymphoid proliferations of the salivary glands: lymphoepithelial sialadenitis vs low-grade B-cell lymphoma of the malt type. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2000;109:1170-1175. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 40. | De Vita S, De Marchi G, Sacco S, Gremese E, Fabris M, Ferraccioli G. Preliminary classification of nonmalignant B cell proliferation in Sjögren's syndrome: perspectives on pathobiology and treatment based on an integrated clinico-pathologic and molecular study approach. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2001;27:757-766. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 41. | Kurtin PJ. How do you distinguish benign from malignant extranodal small B-cell proliferations? Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;111:S119-S125. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 42. | Bacon CM, Du MQ, Dogan A. Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma: a practical guide for pathologists. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:361-372. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 43. | De Vita S, Gandolfo S. Predicting lymphoma development in patients with Sjögren's syndrome. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2019;15:929-938. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 44. | Nishishinya MB, Pereda CA, Muñoz-Fernández S, Pego-Reigosa JM, Rúa-Figueroa I, Andreu JL, Fernández-Castro M, Rosas J, Loza Santamaría E. Identification of lymphoma predictors in patients with primary Sjögren's syndrome: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Int. 2015;35:17-26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 45. | Nocturne G, Virone A, Ng WF, Le Guern V, Hachulla E, Cornec D, Daien C, Vittecoq O, Bienvenu B, Marcelli C, Wendling D, Amoura Z, Dhote R, Lavigne C, Fior R, Gottenberg JE, Seror R, Mariette X. Rheumatoid Factor and Disease Activity Are Independent Predictors of Lymphoma in Primary Sjögren's Syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:977-985. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 46. | Risselada AP, Kruize AA, Goldschmeding R, Lafeber FP, Bijlsma JW, van Roon JA. The prognostic value of routinely performed minor salivary gland assessments in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:1537-1540. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] |