As the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) has steadily increased in the United States, so has the awareness of central sleep apnea (CSA). The hallmark of CSA is transient cessation of airflow during sleep due to a lack of respiratory effort triggered by the brain. This is in contrast to OSA, in which there is absence of airflow despite continued ventilatory effort due to physical airflow obstruction. The gold standard for the diagnosis and optimal treatment assessment of CSA is inlaboratory polysomnography (PSG) with esophageal manometry, but in practice, respiratory effort is generally estimated through oronasal flow and respiratory inductance plethysmography bands placed on the chest and abdomen during PSG.

Background

The literature has demonstrated a higher prevalence of moderate-to-severe OSA in the general population compared with that of CSA. While OSA is associated with worse clinical outcomes, more evidence is needed on the long-term clinical impact and optimal treatment strategies for CSA.1 CSA is overrepresented among certain clinical populations. CSA is not frequently diagnosed in the active-duty population, but is increasing in the veteran population, especially in those with heart failure (HF), stroke, neuromuscular disorders, and opioid use. It is associated with increased admissions related to comorbid cardiovascular disorders and to an increased risk of death.2-4 The clinical concerns with CSA parallel those of OSA. The absence of respiration (apneas and hypopneas due to lack of effort) results in sympathetic surge, compromise of oxygenation and ventilation, sleep fragmentation, and elevation in blood pressure. Symptoms such as excessive daytime sleepiness, morning headaches, witnessed apneas, and nocturnal arrhythmias are shared between the 2 disorders.

Ventilatory instability is the most widely accepted mechanism leading to CSA in patients. Loop gain is the concept used to explain ventilatory control. This feedback loop is influenced by controller gain (primarily represented by central and peripheral chemoreceptors causing changes in ventilation due to PaCO2 [partial pressure of CO2 in arterial blood] fluctuations), plant gain (includes lungs and respiratory muscles and their ability to eliminate CO2), and circulation time (feedback between controller and plant).5

High loop gain and narrow CO2 reserve contribute to ventilatory instability in CSA.6 Those with high loop gain have increased sensitivity to changes in CO2. These patients tend to overbreathe in response to smaller increases in PaCO2 compared with those with low loop gain. Once the PaCO2 falls below an individual’s apneic threshold (AT), an apnea will occur.7 The brainstem then pauses ventilation to allow the PaCO2 to rise back above the AT. CSAs also can occur in healthy individuals as they transition from wakefulness into non–rapid eye movement (REM) sleep in a phenomenon called sleep state oscillation, with a mechanism that is similar to hyperventilation-induced CSAs described earlier.

Primary CSA has been defined in the International Classification of Sleep Disorders 3rd edition (ICSD-3) with the following criteria: (1) diagnostic PSG with ≥ 5 events per hour of CSAs and/or central hypopneas per hour of sleep; the number of CSAs and/or central hypopneas is > 50% of the total number of apneas and hypopneas; and there is no evidence of Cheyne-Stokes breathing (CSB); (2) the patient reports sleepiness, awakening with shortness of breath, snoring, witnessed apneas, or insomnia; (3) there is no evidence of nocturnal hypoventilation; and (4) the disorder is not better explained by another medical use, substance use disorder (SUD), or other current sleep, medical, or neurologic disorder.8

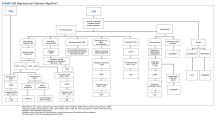

A systematic clinical approach should be used to identify and treat CSA (Figure).6,7

Adult CSA can be divided into 2 main categories based on the blood gas CO2 levels on awakening. The first type is eucapnic/hypocapnic (nonhypercapnic) CSA, which can further be subdivided into HF-induced CSA, treatment-emergent CSA, altitude-induced CSA, CSA induced by renal failure or other comorbidities, and idiopathic CSA. The second type is hypercapnic CSA, which can be further subdivided into drug-induced CSA and neuromuscular CSA. Strokes can induce hypercapnic or hypocapnic CSA.The purpose of this review is to familiarize the primary care community with CSA to aid in the identification and management of this breathing disturbance.