Abstract

This exploratory, qualitative study considers how online home-based businesses offer opportunities for ethnic entrepreneurs to ‘break out’ of traditional highly competitive and low margin sectors. Previous studies have found a positive association between ethnic minorities’ high levels of entrepreneurship and home computer use in ethnic groups. Despite these associations, previous studies have overlooked the particular opportunities offered by home-based online businesses to ethnic entrepreneurs. The study adopts mixed embeddedness as a theoretical lens to guide interviews with 22 ethnic entrepreneurs who have started online home-based businesses in the UK. We find online home-based businesses offer ethnic entrepreneurs novel opportunities to draw on their ethnic advantages and address the constraints they face. The unique affordances of this type of business allow entrepreneurs to develop the necessary IT skills by self-learning and experimentation and to sub-contract more difficult or time consuming aspects to others. The findings also show that, consistent with the theory of mixed embeddedness, whilst the entrepreneurs are influenced by social, economic and institutional forces, online businesses allow them to exert their own agency and provide opportunities to uniquely shape these forces.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Prior research has found that ethnic minorities in many developed countries are associated with high levels of entrepreneurship, with recent migrants having a particularly high propensity to engage in new business activity (Levie, 2007). This effect is particularly marked in liberal economies, such as the UK, where conditions are more favourable to business start-up than other European countries and which has resulted in significant growth in the number of ethnic enterprises (Altinay and Altinay, 2008; Ram and Jones, 2008). However, whilst there are significant numbers of ethnic enterprises, the majority of these are confined to low margin and highly competitive sectors. For example, catering, clothing and retail by Indians, Pakistanis and Bangladeshis, the take-away food sector by Chinese and hairdressing and construction by African- Caribbeans (Azmat, 2010; Dana and Morris, 2007; Edwards and Ram, 2006). The confinement of ethnic enterprises to such ‘poorly rewarded and fiercely competitive sectors’ (Ram and Jones, 2008, p.64), has led these and other authors to call for the promotion of opportunities for diversification and ‘break out’ for ethnic entrepreneurs.

Since the widespread adoption of the internet in the late 1990s, there has been considerable interest and research on online or e-businesses, and the unique opportunities and challenges that these offer (Amit and Zott, 2001). More recently, as the domain of online business has matured and broadened into distinct sub-domains, there has been a growing and distinct stream of studies that consider online home-based businesses (Gelderen et al., 2008; Anwar and Daniel, 2014; Daniel et al., 2014). Such businesses combine the opportunities afforded by both online and home-based ventures, such as the ability to set a very low affordable loss (Sarasvathy, 2001), which may be attractive to entrepreneurs that cannot raise external financing or who have limited personal resources. However, the combination of the online medium and the home-base also exacerbate the challenges manifested in the two types of business, for example, engendering feelings of isolation and difficulties in establishing trust (Anwar and Daniel, 2014).

Research aims and questions

Previous studies have found a positive association between home computer use and entrepreneurship in ethnic groups in the US (Fairlie, 2006). This suggests that ethnic groups perceive that the online environment offers them entrepreneurial opportunities. Despite this positive association, no previous studies have explored the formation of home-based or other online businesses by ethnic entrepreneurs. The study addresses this research gap by addressing three inter-related questions that follow the accepted approach to developing qualitative exploratory studies (Weick, 2007; Smith et al., 2013). The first question takes the necessary initial step to establish ‘what’ is occurring in the context of study: what types of online home-based businesses are being operated by ethnic entrepreneurs? The second question builds on this to explore ‘how’ the effects established by the first question came to be (Bryman, 2004; Bryman and Bell, 2007; Weick, 2007): how do the characteristics of online home-based businesses afford opportunities to ethnic entrepreneurs? The third question builds on the previous two questions to provide an explanation (a ‘why’) of the observed phenomena (the ‘what’) and its operation (the ‘how’). This explanation is most often provided by drawing on theory, in the case of this study the theory of mixed embeddedness: why online home-based entrepreneurs are both influenced by, and influence, social, economic and institutional forces? These three questions are important to provide a theoretically based understanding of the opportunities online home-based businesses offer to ethnic entrepreneurs in the UK. In addition to providing an understanding of this important group of entrepreneurs and this significant business type, this study provides a basis and comparator for future studies of other entrepreneurial groups adopting this type of business.

In the following sections we review the two bodies of literature relevant to this study: prior studies of online home-based businesses and studies of ethnic entrepreneurship that draw on the theory of mixed embeddedness. We then describe the method adopted for the empirical stages of this study. We present the findings of the study organised according to the three research questions. We follow this with a discussion of the findings and our conclusions. We highlight the relevance of our findings for practitioners and policy makers and discuss the limitations of this study and opportunities for future research.

Entrepreneurship and online home-based businesses

We draw on the widely accepted definition of entrepreneurship proposed by Shane and Venkataraman (2000, p.218) in their seminal paper: ‘the processes of discovery, evaluation, and exploitation of opportunities; and the set of individuals who discover, evaluate, and exploit them’. Entrepreneurship is not the sole preserve of small organisations. Large organisations can also develop highly novel approaches to delivering customer value, in what is often termed intrapreneurship or corporate entrepreneurship (Halme et al., 2012; Burns, 2012). Similarly, not all small organisations are entrepreneurial; since some may be following well tried and tested approaches (Van Wyk and Boshoff, 2004).

In the case of online businesses, those involved are deliberately seeking to leverage the flexibility of the online environment to provide novel value to their customers, often through lower cost, enhanced choice, rapid fulfilment, increased socialisation or combinations of these (e.g. Zhang et al., 2014; Shin, 2014). The vast number of online ventures requires those entering this domain to develop novel ways to compete. Those operating their online businesses from home are additionally seeking to provide value whilst maintaining extremely low operating costs, requiring them to find creative ways to leverage and combine limited resources (Daniel et al. 2015; Di Domenico et al., 2014). Hence, whilst we would not claim that all online home-based businesses are entrepreneurial, the flexibility offered by the online environment, the high levels of competition and the need to creatively use limited resources, result in many online businesses being highly entrepreneurial in nature, resulting in them being recognised as a source of innovation and business diversity (Gelderen et al., 2008; Gagliardi, 2013). Our study is limited to individuals and businesses that meet Shane and Venkataraman’s (2000) definition given above. That is, their businesses demonstrated the discovery, evaluation and exploitation of novel opportunities, such as addressing customers that were not currently served (exploitation) or developing new products or services (discovery).

Home-based and online home-based businesses: prior literature

Previous studies of home-based businesses tend to be highly descriptive and a-theoretical (e.g. Betts and Huzey, 2009; Clark and Douglas 2009–2010; Mason et al., 2011). Studies that seek to theorise home-based businesses have tended to consider a particular aspect of such businesses, such as gender (Bryant, 2000; Walker and Webster, 2004; Nansen et al. 2010) or isolation (Smith and Markham, 1998; Smith and Calasanti, 2005; Golden et al., 2008) and apply specific theories that focus on these singular aspects.

A theoretically grounded perspective of home-businesses can be obtained by turning to the domain of micro-businesses. Micro businesses are frequently defined as businesses with less than 10 employees (e.g. Europen Union 2016). Micro businesses are theorised as flexible, creative and able to adapt quickly to changing context and opportunities (Baines and Wheelock, 2000; Pretorius et al., 2005). They are also theorised as ‘staying close to the customer’, which has been characterised as entrepreneurial marketing (Morrish et al., 2010; Anwar and Daniel, 2016a). Micro businesses have also been associated with providing economic and social opportunity. In addition to allowing entrepreneurs to pursue interests (pull motivation), micro businesses formation also provides opportunities those who have had to leave paid employment (i.e. a push motivation) and the number of micro businesses such as home based businesses, is often counter cyclic with economic and paid employment growth (Clark and Drinkwater, 2000; 2010). Whilst micro businesses provide significant opportunities, they also present severe challenges. The failure rate of micro businesses is higher than for small, medium or larger businesses (Fajnzylber et al. 2006). The higher failure rate is attributed to lower resources, meaning that micro businesses are less able to withstand shocks. The high failure rate has also been attributed to limited managerial experience, with managers learning about operating their business only once they have begun (Harrison and Leitch, 2005; Keith et al., 2016).

More recently, home-based entrepreneurs and their businesses have been theorised through entrepreneur-venture fit (Anwar and Daniel, 2016b), an approach that is derived from the more widely known person-organization fit (Van Vianen, 2000; Billsberry et al., 2005). Person-organization fit is based on the premise of an individual joining a pre-existing organization with an established set of organizational characteristics. Entrepreneur-venture fit differs in that it describes how entrepreneurs will seek to establish ventures that either addresses their needs or draws on their abilities. Home-based businesses can provide either, or both, of these types of fit: for example meeting the need to stay in the home due to caring responsibilities or drawing on specialist abilities that can be provided effectively the home (Gelderen et al., 2008; Anwar and Daniel, 2016b).

Ethnic entrepreneurship and mixed embeddedness prior literature

Quantitative studies have found differences across ethnic groups in the frequency or rate of self-employment and the industry sectors that are most popular with different ethnic groups. Table 1 shows the self-employment rate (defined as the percentage of people in employment who are self-employed) varies amongst males from 31.3% for Pakistanis to 10.5% for Black Africans (Clark and Drinkwater, 2010). Table 1 also shows that the rate for female participation in self-employment also varies across ethnic groups, and is lower than the rate for males in the same ethnic group. Daniel, DiDomenico, et al. (2015) found participation in industry sectors varied by ethnic group, as shown in Table 2. Whilst their study did not differentiate businesses based at home from those based in commercial premises, they found that participation in the ICT/Professional and Financial Services sector, which includes similar types of businesses to our sample, varied from 34.6% for Caribbean and Africans to 16.3% for South Asians.

A number of theories have been proposed to explain the entrepreneurial orientation of ethnic groups. The most frequently used are cultural theory, disadvantage theory and mixed embeddedness (Azmat, 2010). Cultural theory posits that aspects such as social norms, beliefs and family ties influence ethnic entrepreneurs to start businesses, the type of business formed and the outcome of those businesses (Volery, 2007). As we have noted previously, whilst concentrations of certain ethnic groups in sectors, such as retail and take-away foods, is consistent with cultural theory, there is no recognition of other factors that have been shown to influence business start-up, such as relative position in the labour market or market opportunity (Levie, 2007). Disadvantage theory addresses the first of these aspects, suggesting that the high rate of ethnic start-ups is due to their relative disadvantage in the labour market, for example, due to limited language skills or non-recognition of overseas qualifications (Light and Gold, 2000; Ley, 2006).

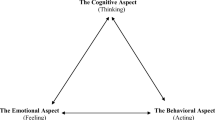

The theory of mixed embeddedness seeks to address the narrow perspectives of these theories by situating ethnic entrepreneurs in their wider social, economic and institutional or political setting, with a consideration of how these influence ethnic business start-up and ongoing operation (Kloosterman et al., 1999; Jones and Ram, 2007). As Kloosterman (2010) later expands, issues and opportunities experienced by the entrepreneur are influenced by what he refers to as the opportunity structure, where ‘the opportunity structure is itself a product of socio-economic and institutional forces’ (p.41). The dimensions of mixed embeddedness are purposefully broad, pluralist and undeterministic (Kloosterman, 2010) in order to reflect the many forces shaping the opportunities of entrepreneurs.

Whilst this makes the theory both powerful and flexible, it presents challenges when using it as a guide to data collection and analysis in empirical studies. As noted by Ram and Smallbone (2001), ‘there is no consensus on what such features [of the mixed embeddedness framework] should comprise’ (p.11). These authors collect and analyse data on: sector, size, location, access to finance, social networks, generational differences and institutions. Other studies collect and analyse data on: political economy, social ties, residential proximity and fitting in with workplace behaviours (Rath, 2002); enterprise support, urban regeneration and economic deregulation (Barrett et al., 2001); sector, educational attainment, informal and formal support organisations (Price and Chacko, 2009).

Despite its broad perspective, we suggest the theory of mixed embeddedness has a number of limitations. Firstly, it posits that the social, economic and institutional setting will exert forces on ethnic entrepreneurs, suggesting that forces act in only one direction and that entrepreneurs are victims or pawns, with little individual or collective agency. To date, there is very limited discussion of the role of agency in consideration of the mixed embedded perspective (for an exception see, Trupp, 2015). We suggest that the entrepreneurs may exert agency in at least two ways. They can elect to start enterprises that do not conform to, or even challenge the constraints of the social, economic and institutional context in which they find themselves. Alternatively, they may create enterprises that are not only influenced by the environment in which they operate, but those businesses can influence that environment. As we have noted previously, and has been observed by other researchers, the broad scope of mixed embeddedness presents challenges when using this theory to guide data collection and analysis (e.g. Ram and Smallbone, 2001; Rath, 2002; Barrett et al., 2001). Another limitation of mixed embeddedness theory and the related opportunity structure model is the focus on the start-up phase of ventures, with little guidance and insight on the how embeddedness changes over time and hence shapes and explicates aspects such as venture growth and maturity (Jones et al., 2014). This limitation results in a cross-sectional, rather than processual, consideration of entrepreneurship (McMullen and Dimov, 2013; Kloosterman and Rath, 2001)

Methods

The paper is an exploratory qualitative study of a specific type of entrepreneurship: ethnic entrepreneurs operating online home-based businesses. These entrepreneurs, operating this type of business, have not been studied before. An exploratory qualitative approach is a well-recognised approach to investigating a new area (Bryman, 2004; Bryman and Bell, 2007). Rather than seek to be statistically representative and present frequencies and trend data, qualitative studies seek to provide rich descriptions and identify the issues and themes that are important in the new context being explored (Smith et al., 2013; Suddaby et al., 2015). Qualitative studies therefore seek to address ‘what’, ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions that are important to understand when first exploring a topic, and such as we pose in this paper. Subsequent studies can then build on the important foundational work of exploratory studies. Confirmatory, quantitative studies can seek to address question such as ‘how many’ by identifying statistically representative samples and providing frequency analysis. Our study provides a theoretical understanding of the domain by drawing on the theory of mixed embeddedness.

We adopted a qualitative and exploratory research method based on key informant interviews. This represents a well-accepted exploratory research method (Kumar et al., 1993) that enables researchers to access the multi-faceted lived-experiences of a wide range of respondents (Dibbern et al., 2008). This method also allows for a progressive, iterative and reflexive approach to data gathering and theorising which is important in exploratory studies (Alvesson, 2003).

Key informant enrolment

The population of interest was key informants who were from an ethnic background and who had formed and operated online businesses at home. The online home-based businesses were consistent with the definition of these types of business provided earlier and included: online retailing, web design, digital marketing services, IT consultancy and business services.

We used three approaches to identify and recruit possible key informants. First, we adopted a purposive sampling strategy (Easterby-Smith et al., 2008) in which the researchers identified four entrepreneurs matching the study’s requirements, and known to them personally, who were then approached to participate. All agreed to take part in the study. Second, we adopted a snowballing approach (Bryman, 2004) by asking the first informants to identify others who had started home-based online businesses matching the requirements of our study. Ten additional participants were identified through this approach. Third, we used the web, particularly social networking services in order to identify individuals who appeared to fit our population of interest. Having interviewed ethnic entrepreneurs using the first two methods of enrollment (personal contacts and snowballing), the names of those interviewees were added to the LinkedIn, Facebook and Twitter accounts of the researchers. This resulted in these social media sites suggesting other contacts with similar characteristics, who were then approached to ascertain fit with the required study characteristics and willingness to participate. Five additional informants were identified and recruited from this approach. Our total sample consisted of 22 key informants.

We recognized the possibility that our three approaches to identifying key informants could be prone to self-selection bias (Bryman and Bell, 2007), with agreement to participate being more likely among entrepreneurs who viewed themselves or their businesses as positively framed. However, our focus was not on the success of the firm per se but on patterns of entrepreneurial activity in their social, economic and institutional settings.

Table 3 presents a summary of the key variables across the sample, including: gender, age, qualifications, country of origin, visa type and nature of their online home-based business.

All the businesses were active and viable when the interviews took place; however, we did not set limits on how long they had been in operation. Of the key informants, 19 were male and 3 were female, which is consistent with the quantitative study of Clark and Drinkwater (2010) which showed the participation of females is lower in self-employment than males for all ethnic groups (see Table 1). Whilst we did not seek to generate a stratified sample reflecting the incidence of male or female ownership of home-based businesses, our preponderance of male informants challenges the popular notion that home-based businesses are more often run by females, leading to them being termed as ‘kitchen-table’ or ‘pink collar’ businesses (Sulaiman et al., 2009). Consistent with previous studies that have found online entrepreneurs tend to be well-educated (Deschamps et al., 1998), 77% of our sample had a first or higher degree (Table 3). The average age of the informants was 39 years, with a minimum age of 24 years and maximum age of 62 years. This wide spread in ages is consistent with previous studies of online entrepreneurs that have found that they have a wide spread in ages similar to that found in other types of entrepreneur (Deschamps et al., 1998). Whilst the majority of the interviewees (41%) had a British passport, a similar proportion (36%) were on entrepreneur visas or had applied for one, suggesting this is an important means of attracting entrepreneurs to the UK. The remaining 14% had EU passports (see Table 3).

Consistent with our reflexive approach to our data collection and interpretation, we recognise that our lead interviewer was an Asian male, and taken with the implicit cultural influences possible in a snowballing approach, led to a greater introduction to same gender informants of a similar ethnic background.

Data collection

Data collection was guided by a semi-structured interview schedule (Punch, 2005). The schedule design followed the ideas of narrative interviewing in which informants are encouraged to tell their story relating to the subject of study (Larty and Hamilton, 2011; Bryman, 2004). We initially used broad questions such as “tell me the story of your business - why you started it and how you started it” to encourage respondents to describe their experiences and perspectives, rather than being led by the interviewer.

Most of the interviews were conducted face-to-face (16) with the remaining 6 being undertaken by telephone. Again, in the majority of cases (14), interviews took place in the business location of the entrepreneur’s home. In five cases, the entrepreneur asked to meet in a public location such as a café. Conducting face-to-face interviews in the home-based setting of the majority of businesses enabled us to collect field notes on aspects such as use of space in the home and promotional signage outside the home. In addition to the field notes, the data were supplemented with other sources (Denzin and Lincoln, 1998), such as examination of the businesses’ websites and press coverage.

Data analysis

All of the interviews were recorded. In four cases, interviews were conducted by two interviewers, allowing field note comparison to aid understanding and internal validity of the study. In all other cases, interviews were undertaken by the same single interviewer. The researchers followed an iterative approach to data collection (Strauss and Corbin, 1990), jointly reflecting on each interview before subsequent interviews were undertaken.

Interview transcripts and field notes were coded using Nvivo software. The well-accepted three-level approach to coding suggested by Miles and Huberman (1984) and followed by others (e.g. Dey, 1993; Richards, 2005) was followed. In this three types of codes were identified in the data: descriptive, topic and analytical (Richards, 2005). Descriptive codes identified attributes such as type of business, educational level, gender. Topic codes captured the subjects covered in respondents’ answers and largely followed the interview guide, but not limited by this. Finally, analytical codes captured explanations provided directly by the respondents or that could be inferred by the researchers from responses, for example, when respondents explained that operating an online business allowed them to start a business with limited capital. Codes were given an appropriate name. Each interview was analysed and then the resulting codes were aggregated across the interviews, combining data where the codes were similar, and seeking further explanations (captured in new or refined codes) where different codes or interpretations had been identified (Miles and Huberman, 1984). The three levels of resulting codes, descriptive, topic and analytical were drawn on to address the three research questions (Miles and Huberman, 1984). This three level approach is consistent with our research aim of exploring an under-researched domain as it has an inductive nature which allows the data to directly inform the findings of the study, rather than be constrained by prior models.

Internal validity was increased by the two researchers undertaking coding of the first three interview transcripts independently. Whilst consistency was high, differences were discussed and resolved. Subsequent coding was undertaken by the lead researcher with the coding being reviewed by the second researcher.

Results

Types of online home-based businesses

Our first research question considers the types of online home-based businesses being operated by ethnic entrepreneurs. Analysis of the descriptions given by the informants suggests the types of online home-based businesses can be clustered into two groups: those based on IT skills of the individual entrepreneur (64% - see Table 3), and those that draw on other skills or interests and where the entrepreneur often has very few IT skills (36% - see Table 3).

Considering the first of these, businesses based on IT skills include: web design, web hosting, IT consulting, search engine optimization, digital marketing, IT security and IT networking. In most cases the choice of business arose from the skills of the entrepreneur, skills that were often either gained or reinforced by formal education. As shown in Table 4, whilst a similar proportion of entrepreneurs running both types of businesses had bachelors and masters degrees (79% and 75% - see Table 4), those operating IT-based online home-based businesses had a higher proportion of formal qualifications in areas such as computing and e-marketing (64% - see Table 4) compared to those operating non-IT based businesses (13%). An online home-based business allows individuals with the specialist expertise provided by formal education to use this expertise to launch their own business, as described by informant 2:

I am from Bangladesh, but I am trying to be an entrepreneur in this country, and I want to establish my own business where I've got the expertise. My expertise is in computing. I have my honours in computer engineering from the University of Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Turkey, and then with a full scholarship. Then I had my Masters from the University of Bedfordshire.

The second group of entrepreneurs (informants 15 – 22) were operating online business that did not rely on IT expertise. Indeed, these informants were often keen to stress that they had little IT knowledge. They managed this lack of knowledge in two different ways. Some felt that it was not necessary for them to know about IT, and like other activities related to their business, this could be outsourced, as described by informant 15, who was selling designer clothes online:

I've just been trying to decide which things I need to learn about.. and which things are going to be a waste of time. For me, sewing, for example, is a waste of time. …. The same with the IT side. It just never occurred to me to do anything myself, to be honest. I thought, what's the point, there are lots of people out there who can do it for me.

Others felt that since the online aspect was central to their business, they did not want to be reliant on others, particularly for simple IT tasks, and so sought to teach themselves the relevant skills. As for those in the first group of companies, the online environment was conducive to this self-learning since it allows learning by doing, experimentation, the ability to search for information and the ability to request solutions to problems in online forums, as described by informant 18 who was selling Asian jewellery online:

I'm doing the qualifications for IT now, actually, because I taught myself, you see, using a computer… So, everything I've learnt on IT is self-taught…

For the group of online entrepreneurs without prior IT skills and qualifications, an online home-based business offered them an opportunity to leverage their other skills and expertise. For example, informants 19 – 21 were qualified accountants and used their online business to find customers for their accountancy services.

For others the relative ease of launching an online home-based business offered the opportunity to pursue interests away from their formal qualifications. Informant 15, who was educated and working as a doctor, described how her business had allowed her to pursue something she found more personally fulfilling:

The other big thing is that I really wanted to do something very different from my day job. I wanted to do something creative, ….I'd gone on a few trips abroad with a couple of medical charities….That was what made me more interested in doing something that would provide some cultural input for me.

The affordances of online home-based businesses

Our second research question considers how the characteristics of online home-based businesses afford opportunities to ethnic entrepreneurs. The informants were emphatic that the characteristics of online home-based businesses, which have been recognised in previous studies and were discussed in the literature review, had been influential in them setting up their own business. Characteristics that appear to have been most influential were: low cost of start-up and hence low initial funding, ability to launch and run the business alongside other income earning activities, flexibility of work location and the potential financial rewards of running their own business.

For example, informant 12 stressed how the combination of online and operation from the home meant that there were few costs associated with starting his search engine optimization business, but he was keen to stress that there were other challenges:

We just made a website, and entry is very easy. This is one of the benefits. Entry is so easy, and you don’t need any money. You start earning straightaway. But you know, entrance is easy, but managing that reputation and that standard is very, very difficult, and that is the real challenge of working from home.

The very low initial costs, compared to other types of business, meant that informants were able to fund their businesses either from their own sources, or from their family. None of the informants had sought bank or venture capital funding for their ventures. Funding from their family often included funding from their extended family in their country of origin and was without obligation, demonstrating the social and cultural support consistent with our mixed embeddedness perspective. This familial support was described by informant 2:

No, most of the funding basically we got from back home ….about half of the funding I got from my family back home….My father gave me a gift, you can say.

The ability to launch and run an online home-based business alongside other income earning activities, termed multiple incomes by Gelderen et al. (2008), also helped reduce the need to raise initial funding, since business costs and costs of living for the informants could be supported from their other income sources. This also allowed the informants to undertake a ‘soft launch’ for their business, where they could learn and experiment, before fully committing to the business. For example, informant 15 continued to work as a doctor whilst she started her business and informant worked as a taxi driver whilst establishing his online home-based networking business.

The ability to be able to work at any location and at any time is a well-documented benefit of online working Mason (2009–2010). This appeared a particularly important feature for many of the informants, perhaps more so than for non-ethnic groups. This appeared to be for a number of reasons: many of them travelled regularly and for extended periods, often returning to their country of origin, they often employed staff or contractors in overseas countries and supported clients overseas, again often in their country of origin. Informant 12 described that the ability to work from any location allowed him to run an office in Pakistan, although he was based in the UK:

Well, I am a single owner, but I have other people who are working for me. Initially I managed like a virtual team, three contractors, and there are two in different countries, but now I have an office as well back in Pakistan, and I am here [in the UK]. So I am still managing it like virtually.

Mixed embeddedness theory to explore ethnic online home-based businesses

Our third research question draws on the theory of mixed embeddedness to consider why online home-based entrepreneurs are both influenced by, and influence, social, economic and institutional forces? As discussed in the literature review section, the notion of mixed embeddedness is extensive, covering an extensive array of explicit and implicit influences on ethnic businesses. Our inductive approach to data analysis identified five highly salient sub dimensions: two social ones; family/friends and cultural; two economic ones; market sector and customers and one institutional one; visas.

Social: family/friends

The majority of informants reported significant influence and support from their families on the formation of their businesses. For example, Informant 18 described how her brother-in-law had allowed her to start her online jewellery business by providing her with stock on a sale-or-return basis:

My brother-in-law, he's always buying and selling items himself; all sorts …they said, why don't you have a go? It could be something to do; an income, and if you manage to sell it and you make a profit, then you can pay me for your lot, otherwise I'll just take it back.

As described in the previous section, the majority of the informants had received financial support from their families, which was eased by the very low start-up costs of online home-based businesses. Many of the informants also described how their families continued to provide ongoing support for their businesses. In some cases, particularly for 2nd and later generation informants, close families were mainly based in the UK, but some extended family was in their country of origin. For individuals who had recently migrated to the UK, much of their family was in their country of origin. Both of these instances provided the informants with a strong support network outside of the UK, which the online nature of the business allowed them to leverage more directly than for many offline businesses.

Social: cultural

Informants described how an emphasis on entrepreneurship within the culture of their country of origin often existed, which had been passed on to them through their parents acting as role models. For example, informant 13 described how he thought his Italian background and parents may have influenced him to start his own business:

Maybe it's because of my Italian background because in Italy everybody's got their own business. It's not people working for companies. It's very rare. There are big companies as well but mainly people with their own small business and they build their own small factory if they can, if they manage, or they work from home.

The informants also described how culture influenced the type of business they started or the products that they sold. For example, informant 15 designed and sold ladies clothes. Whilst she did not want to categorised the clothes she sold as Islamic, she recognised that they were influenced by her cultural background:

I'm Asian, I'm Bengali and you make a choice between wearing completely English clothes or Western clothes, or completely wearing Asian clothes. ….What I wanted really was to try and produce something that expressed both of those identities. …..

Some informants highlighted how, if they either had employees or customers in their country of origin, and they were operating their business in the UK it was important to understand and recognise differences in both cultures. For example, informant 12 used the matter of festivals to highlight differences between Pakistan and the UK:

Yes, I mean there are challenges.... One is cultural, for example, like festivals....Pakistani and Indian culture are not very different. But maybe if someone from the UK is working directly with them, they might have more problems initially. But it is less problems for me, and coming here [to the UK] really helped me because I understand; now I understand the working culture over here better.

Economic: market sector

Compared to the market sectors traditionally associated with ethnic groups (Altinay and Altinay, 2008; Altinay, 2010), the majority of the informants had entered sectors, which whilst highly competitive, are growth sectors, such as web hosting, e-marketing and business services, and therefore offer the opportunities for reasonable revenues. The extremely low operating costs of online home-based businesses helped ensure that the informants could retain a significant proportion of these revenues as profits, resulting in the financial rewards described by some of the informants. For example, informant 12 was candid about the financial attractiveness of his business, particularly compared to being employed in his original country:

It’s good, you know, financially it’s very good. ….I mean an employer cannot pay me a large sum, you know, and in the Pakistani market I was not getting that much. Now I have a number of clients and I am getting, you know, earning much more. So, financially you are much more comfortable here.

The market sectors chosen, particularly those that were based on IT skills (informants 1–16) were also global in nature, hence these businesses could attract and serve customers from around the world. They could also employ staff based around the world, since IT expertise is internationally recognised and transferrable and staff did not need to be based in the UK as they could do their work remotely. The international background of the informants appeared to encourage them to both seek customers, and particularly hire staff from overseas, often from their own country of origin.

Other features of the online medium also support the ability for ethnic minorities to be able to operate successfully in growing market sectors. For example, previous studies have suggested that poor language skills can often be a barrier for ethnic minorities in achieving employment or business success (Volery, 2007). Informant 2 reinforced the importance of language in winning trust of customers:

For a visa, if you have got a degree from the UK, you do not need to have an English requirement. But I am talking about in the concept of the business, because for example, I came from Bangladesh, and if my English is not that good, if I talk to an English person, a businessman, if that Englishman does not feel confident in me, then that man will not give me the business. ….

Informants described how the online medium reduced the need for direct communication and hence reduced the emphasis on language competence. For example, the informants used their web sites to present their businesses and feedback and ratings from customers could be drawn on to show their abilities to do the required work.

Economic: customers

Studies using mixed embeddedness as a theoretical lens suggest that ethnic entrepreneurs in traditional offline sectors are limited to customers located in close spatial proximity (Ramsden, 2008). If they are located in a non-affluent neighbourhood, this may result in them being limited to customers with limited financial means. Even if financial constraints are not an issue, it may limit them to a highly homogeneous customer base, resulting in difficulty in diversifying their business, and hence decreasing their ability to learn, develop new products or services and reduce exposure to risk. For example, informant 12 described how serving international clients allowed him to learn different skills:

If you have your own business and different clients from different cultures, different backgrounds, different industries, so you get many, many opportunities to learn more. So, I have learnt a lot.

Some of the informants described how they were mostly reliant on customers from similar ethnic backgrounds to their own, often because referral networks operated within cultural groups. For example, informant 2 described how the majority of the clients of his web development business had a similar background to himself:

I am from Bangladesh, and the area, it is Luton, and most of the time I go to London and these two places we have got a lot of immigrants from Asia. …. So these people, sometimes they help us. Maybe because of ethnicity, … They are referring us from one to another.

Informants whose businesses had been operating for longer, or whose businesses had become successful relatively quickly, stressed how they were not reliant on customers either from similar ethnic backgrounds or from their geographic location. For example, informant 18 described how she attracted non-Asian customers to buy her jewellery:

You'd be surprised, not all my customers are Asians. Some of them are English, as well. Quite a few are English ladies getting into some of the… they get the more intricate, like earrings, and so on, when I've sold earrings on their own, and broaches. So, you get a variety of customers.

Institutional: visas

The informants mentioned a number of forces acting on their businesses that would be considered as institutional in nature. These included: the difficulty of securing bank loans for their business, due to the time remaining on their visas, due to the online and home-based nature of their business or due to the general reluctance of banks to lend to small businesses at the time of the study and the variable availability of broadband infrastructure in the UK, particularly in residential areas where home-based businesses operate.

One institutional issue that was highly pertinent to a number of the informant was the nature and terms and conditions of their visas which allowed them to live and work in the UK. The majority of the informants had British passports (10 of the informants). In some cases, this is because they had been born in the UK or they had qualified for a passport on other grounds. Other informants, who were from the EU, were free to live and work in the UK under the EU’s Open Boarders legislation (3 informants).

The remainder of the informants (9) were living and working in the UK on visas, the majority of which were entrepreneurship visas. Four informants had entrepreneurship visas and three more had applied for these at the time of the study. Under such visas, an entrepreneur, or two entrepreneurs acting as partners, is required to invest at least £50,000 in their business in the UK over the three year period of the visa. During that time they must create two full time jobs, or a number of part-time jobs that are equivalent to two full time positions (UK Borders Agency, 2014). The informants with entrepreneurship visas were emphatic that the characteristics of online home-based businesses explored in our first and second research questions, helped them in being able to establish a business and hence qualify for an entrepreneurship visa. However, being able to maintain or extend that visa requires the entrepreneur to fulfil certain conditions, such as creating employment for others and creating a sustainable business. As was discussed in the literature review section, many home-based businesses expand by ‘jobless growth’ (Mason et al., 2011), that is by subcontracting work to other small businesses, rather than employ staff. Similarly, some respondents felt that the requirement to demonstrate the sustainability of the business after just three years was difficult and arbitrary, as described by informant 21:

I’ll quote Sultan Mohammed Shah in one of his speeches to the entrepreneurs he said that the first thousand days of a business are the really hard ones and you have to stick with it and you have to give, you know, your every piece of your breath if you say and that comprises of three years right. … it’s the fourth year that you show your 100% and you achieve you aims and then you can say there you go.

Discussion and conclusion

The theory of mixed embeddedness suggests that ethnic entrepreneurs are constrained to operate in a limited social, economic and institutional context, which influences the nature and success of the businesses undertaken. Whilst this theory appears to fit a number of examples of ethnic entrepreneurship, it suggests that the entrepreneurs have limited choice over the business sectors they operate in, suggesting that they have little agency, and limited influence over the context in which they operate their business.

Our findings suggest that online home-based businesses offer opportunities for ethnic entrepreneurs to leverage existing skills or experience. Whilst it may be apparent that such businesses would provide opportunity for entrepreneurs with IT skills, the findings of our first research question demonstrates that this type of business also offers opportunities for entrepreneurs without IT skills. The characteristics of these businesses, explored in our second research question, allow individuals without IT skills to leverage other skills such as accountancy, dress and jewellery design. The ease of operation of many web based systems and platforms allowed those entrepreneurs without IT skills to develop those skills by self-learning and experimentation, and to sub-contract more difficult or time consuming aspects to others.

Our findings provide empirical support for Kloosterman’s (2010) theorised opportunity structure model. In this model, he posits that ethnic entrepreneurs can break out of traditional low skill/low growth sectors, such as corner shops, into high growth sectors. Online businesses can offer the high growth theorised by Kloosterman. However, as he indicates for those with limited human capital who enter high growth sectors that have low thresholds, despite their growth these sectors may become as highly competitive and hence low in reward as the traditional sectors. Our identification of two types of online home-based entrepreneurs, those with IT skills and those without, support the theorisation of high and low threshold sectors within high growth markets (Kloosterman, 2010). Our study shows that low threshold sectors may be particularly prevalent in online businesses due to the relative ease of entry. The entrepreneurs in our study with lower levels of IT skills sought to develop their business by drawing on existing social networks. In offline businesses, the reliance on existing networks can result in limited geographical reach and high levels of competition, and is referred to as enclave economies (Lassalle, 2014). The wide reach of online businesses allowed them to operate beyond local enclaves. Entrepreneurs with higher levels of IT skills were keen to develop and promote their skills rather than rely on existing networks, particularly through gaining formal qualifications. Kloosterman (2010) describes a ‘global elite’ of ‘highly skilled immigrants with their portable skills …. who flock to innovative places where their specific talents can be used best’ (p.36). The significant use of entrepreneurship visas shown in our study highlights the important role of institutional factors highlighted by the mixed embeddedness perspective, in enabling the international physical mobility that is a necessary antecedent of ethnic entrepreneurship.

The study makes a number of inter-related contributions. It extends understanding of the under-research domain of home-based businesses (Di Domenico, 2008; Loscocco and Smith-Hunter, 2004; Walker and Webster, 2004), by focussing on the particular case of online home-based businesses and highlighting the salient characteristics of these sector of home-based businesses. It also brings together two domains of research that have not previously been combined; online home-based businesses and ethnic entrepreneurship. The study also contributes to the growing body of studies that use the theory mixed embeddedness to guide empirical studies. As discussed, the sub-dimensions identified in such studies should be empirically grounded and hence vary across studies according to the specific context of the study. The availability of entrepreneurship visas in the UK at the time of our study, and increased restrictions on other types of visa, made these and important part of the institutional context of our study.

The study finds that online home-based businesses offer ethnic entrepreneurs increased opportunities to choose the type of business that they start and how they operate those business. It therefore provides a compelling argument for inclusion of the notion of entrepreneurial agency in consideration of one of the central theories of ethnic entrepreneurship: mixed embeddedness. We are unaware of extant studies that have suggested such an elaboration of this theory. The study also suggests the need to broaden the frame of analysis in mixed embeddedness studies from contextual forces acting on the entrepreneur and their enterprise, to also include the influence of the entrepreneur and their enterprise on their context. For example, the relative ease with which the informants in the study felt they could hire and manage staff from around the world, and service global customers, due to their own ethnic backgrounds, has been identified as an important component of globalisation (Jones et al., 2012) and which impacts on the competitive environment within which similar businesses operate. Transnational entrepreneurship is being recognised as a distinct entrepreneurial phenomenon (Lin and Tao, 2012; Dimitratos et al., 2016). Whilst transnational entrepreneurs can operate businesses in more than one country, this usually requires physical mobility, usually between their original homeland and adopted country (Drori et al., 2009). Our study adds a novel perspective to transnational entrepreneurship as the online nature of the businesses we studied allowed our ethnic entrepreneurs to leverage their ethnic heritage to successfully operate their businesses in multiple locations, with little or no ongoing physical mobility.

Implications for practice and policy, research limitations and future research

Our study has a number of practice and policy implications. Firstly, many developed economies, including the UK continue to experience high levels of unemployment since the global recession of 2008. Governments have encouraged citizens to become self-employed, both in order to provide employment for themselves, and also to provide employment and economic wealth for others. The quarterly employment figures in the UK released in March 2014 showed that that 65% of the increase in employment witnessed was due to people becoming self-employed (Simpson, 2014), underlining the importance of self-employment to the UK economy.

Immigration policy is an important part of UK Government policy, which continues to be under close interest and scrutiny by the UK press and population. Entrepreneurship visas are seen to be means to attract individuals from countries from outside Europe, who can contribute to the social and economic development of the UK. Whilst much emphasis on immigration is on the existing qualifications and skills (Hunt, 2010), our study shows that the unique characteristics of online home-based businesses can allow individuals with drive and creativity, but without formal qualifications, to operate entrepreneurial businesses, suggesting policy should find ways of moving beyond the emphasis on formal qualifications for the allocation of visa. Similarly, in order to support ethnic entrepreneurs in the UK, or moving to the UK, resources should be invested in increasing the awareness of online home-businesses, providing relevant technical and business education and training, and improving national infrastructure such as broadband access.

There are a number of limitations with our study, which could be addressed in future studies. We recognise that our sample included a high proportion of males, operating IT based online businesses, which is likely to have arisen due to the cultural similarity to the lead interviewer. Future studies should build on this initial qualitative exploration by testing the themes identified in this study in a larger, statistically representative sample that is not based on personal contacts and snowballing. This sample should include as wide a range of types of online home-based businesses as possible, including technology, retail and professional and personal services. Future studies should also include native UK entrepreneurs operating home-based businesses to allow a comparison with ethnic entrepreneurs in order to highlight and hence better understand ethnic effects.

As we have discussed, the theory of mixed embeddedness has a very broad perspective, covering a potentially limitless range of social, economic and institutional factors. In order to use the theory to guide our data collection and interpretation of our findings, we have focussed on a limited set of dimensions. Future studies could consider different or additional dimensions and consider how online home-based entrepreneurs are both influenced by and influence the dimensions considered. Finally, for the purposes of our study we have viewed different types of online home-based businesses broadly homogeneous. Future studies could look at the different opportunities and challenges offered by different types of online business for ethnic entrepreneurs.

References

Alvesson, M. (2003). Beyond neopositivists, romantics, and localists: a reflexive approach to interviews in organizational research. Acad Manag Rev, 28(1), 13–33.

Altinay, L. (2010). Market orientation of small ethnic minority-owned hospitality firms. Int J Hosp Manag, 29(1), 148–156.

Altinay, L., & Altinay, E. (2008). Marketing strategies of ethnic minority businesses in the UK. Serv Ind J, 28(8), 1183–1197.

Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2001). Value creation in e-business. Strateg Manag J, 22(6–7), 493–520.

Anwar, M. N., & Daniel, E. M. (2014). Online Home-based Businesses: Systematic Literature Review and Future Research Agenda (UK Academy of Information Systems Conference). Oxford University. AIS Electronic Library (AISeL). 7 – 9 April. http://aisel.aisnet.org/ukais2014/4. Accessed 15 Feb 2017.

Anwar, M. N., & Daniel, E. M. (2016a). Entrepreneurial marketing in online businesses: the case of ethnic minority entrepreneurs in the UK. Qual Mark Res Int J, 19(3), 310–338.

Anwar, M. N., & Daniel, E. M. (2016b). The Role of Entrepreneur-Venture Fit in Online Home-based Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Literature Review. J Enterp Cult, http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/28771/1/Systemative%20Review%20paper_revised_141116_ACCEPTED%20VERSION_with_Names.pdf.

Azmat, F. (2010). Exploring social responsibility of immigrant entrepreneurs: Do home country contextual factors play a role? Eur Manag J, 28(5), 377–386.

Baines, S., & Wheelock, J. (2000). Work and employment in small businesses: perpetuating and challenging gender traditions. Gend Work Organ, 7(1), 45–56.

Barrett, G. A., Jones, T., & McEvoy, D. (2001). Socio-economic and policy dimensions of the mixed embeddedness of ethnic minority business in Britain. J Ethn Migr Stud, 27(2), 241–258.

Betts, S. C., & Huzey, D. (2009). Building a foundation without brick and mortar: business planning for home based and cyber businesses. Int J Bus Public Adm, 6(2), 50–60.

Billsberry, J., Ambrosini, V., Moss-Jones, J., & Marsh, P. (2005). Some suggestions for mapping organizational member’s sense of fit. J Bus Psychol, 19(4), 555–570.

Bryant, S. (2000). At home on the electronic frontier: work, gender and the information highway. N Technol Work Employ, 15(1), 19–33.

Bryman, A. (2004). Social research methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2007). Business research methods. New York: Oxford University Press.

Burns, P. (2012). Corporate entrepreneurship: innovation and strategy in large organizations. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Clark, D. N., & Douglas, H. (2009–2010). Micro business: Characteristics of home-based business in New Zealand. Small Enterp Res, 17(2), 112–123.

Clark, K., & Drinkwater, S. (2000). Pushed out or pulled in? self-employment among ethnic minorities in England and wales. Labour Econ, 7(5), 603–628.

Clark, K., & Drinkwater, S. (2010). Recent trends in minority ethnic entrepreneurship in Britain. Int Small Bus J, 28(2), 136–146.

Dana, L., & Morris, M. (2007). Towards a synthesis: a model of immigrant and ethnic entrepreneurship. In L. Dana (Ed.), Handbook of research on ethnic entrepreneurship: a co-evolutionary view on resource management (pp. 803–811). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Daniel, E. M., Anwar, M. N., & Henley, A. (2015). Contemporary ethnic minority entrepreneurship in the UK: a quantitative exploration of opportunity structure and break out (Institute for small business and entrepreneurship conference, 11–13 November 2015, Glasgow).

Daniel, E. M., DiDomenico, M. L., & Sharma, S. (2015). Effectuation and home-based online business entrepreneurs. Int Small Bus J, 33(8), 799–823.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (Eds.). (1998). Strategies in qualitative inquiry. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Deschamps, M., Dart, J., & Links, G. (1998). Home-based entrepreneurship in the information age. J Small Bus Entrep, 15(1), 74–96.

Dey, I. (1993). Qualitative data analysis: a user friendly guide for social scientists. London: Routledge.

Dibbern, J., Winkler, J., & Heinzl, A. (2008). Explaining variations in client extra costs between software projects offshored to India. MIS Q, 32(2), 333–366.

Di Domenico, M. (2008). ‘I’m Not just a Housewife’: gendered roles and identities in the home-based hospitality enterprise. Gend Work Organ, 15(4), 313–332.

Di Domenico, M. L., Daniel, E. M., & Nunan, D. (2014). Mental mobility’ in the digital age: entrepreneurs and the online home-based business, New technology. Work Employ, 29(3), 266–281.

Dimitratos, P., Buck, T., Fletcher, M., & Li, N. (2016). The motivation of international entrepreneurship: the case of Chinese transnational entrepreneurs. Int Bus Rev, 25(5), 1103–1113.

Drori, I., Honig, B., & Wright, M. (2009). Transnational entrepreneurship: an emergent field of study. Enterp Theory Pract, 33(5), 1001–1022.

Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. R. (2008). Management research. London: Sage.

Edwards, P., & Ram, M. (2006). Surviving on the margins of the economy: working relationships in small Low-wage firms. J Manag Stud, 43(4), 895–916.

Europen Union. (2016). Eur-Lex: access to European Union Law. Micro-, small- and medium-sized enterprises: definition and scope. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=URISERV%3An26026. Accessed 31 Oct 2016.

Fairlie, R. W. (2006). The personal computer and entrepreneurship. Manag Sci, 52(2), 187–203.

Fajnzylber, P., Maloney, W., & Rojas, G. M. (2006). Microenterprise dynamics in developing countries: How similar are they to those in the industrialized world? evidence from Mexico. World Bank Econ Rev, 20(3), 389–419.

Gagliardi, D. (2013). Next generation entrepreneur: innovation strategy through Web 2.0 technologies in SMEs. Tech Anal Strat Manag, 25(8), 891–904.

Gelderen, M. V., Sayers, J., & Keen, C. (2008). Home-based internet businesses as drivers of variety. J Small Bus Enterp Dev, 15(1), 162–177.

Golden, T. D., Veiga, J. F., & Dino, R. N. (2008). The impact of professional isolation on teleworker job performance and turnover intentions: does time spent teleworking, interacting face-to-face, or having access to communication enhancing technology matter? J Appl Psychol, 93(6), 1412–1421.

Halme, M., Lindeman, S., & Linna, P. (2012). Innovation for inclusive business: intrapreneurial bricolage in multinational corporations. J Manag Stud, 49(4), 743–784.

Harrison, R. T., & Leitch, C. M. (2005). Entrepreneurial learning: researching the interface between learning and the entrepreneurial context. Enterp Theory Pract, 29(4), 351–371.

Hunt, J. (2010). Skilled immigrants’ contribution to innovation and entrepreneurship in the United States. In OECD, Open for business: migrant entrepreneurship in OECD Countries, (pp. 257–272). OECD Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264095830-en. Accessed 15 Feb 2017.

Jones, T., & Ram, M. (2007). Re-embedding the ethnic business agenda. Work Employ Soc, 21(3), 439–457.

Jones, T., Ram, M., Edwards, P., Kiselinchev, A., & Muchenje, L. (2012). New migrant enterprise: novelty or historical continuity? Urban Stud, 49(14), 3159–3176.

Jones, T., Ram, M., Edwards, P., Kiselinchev, A., & Muchenje, L. (2014). Mixed embeddedness and new migrant enterprise in the UK. Entrep Reg Dev, 26(5/6), 500–520.

Keith, N., Unger, J. M., Rauch, A., & Frese, M. (2016). Informal learning and entrepreneurial success: a longitudinal study of deliberate practice among small business owners. Appl Psychol Int Rev, 65(3), 515–540.

Kloosterman, R. C., van der Leun, J. P., & Rath, J. (1999). Mixed embeddedness, migrant entrepreneurship and informal economic activities. Int J Urban Reg Res, 23(2), 253–267.

Kloosterman, R. C., & Rath, J. (2001). Immigrant entrepreneurs in advanced economies: mixed embeddedness further explored. J Ethn Migr Stud, 27(2), 189–201.

Kloosterman, R. C. (2010). Matching opportunities with resources: a framework for analysing (migrant) entrepreneurship from a mixed embeddedness perspective. Entrep Reg Dev, 22(1), 25–45.

Kumar, N., Stern, L. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1993). Conducting inter-organizational research using key informants. Acad Manag J, 36(6), 1633–1651.

Larty, J., & Hamilton, E. (2011). Structural approaches to narrative analysis in entrepreneurship research: exemplars from two researchers. Int Small Bus J, 29(3), 220–237.

Lassalle, P. (2014). The opportunity structure debate revisited: polish entrepreneurs in Glasgow (Institute for small business and entrepreneurship conference, Manchester, 5th- 6th November 2014).

Levie, J. (2007). Immigration, in-migration, ethnicity and entrepreneurship in the united kingdom. Small Bus Econ, 28(2–3), 143–169.

Ley, D. (2006). Explaining variations in business performance among immigrant entrepreneurs in Canada. J Ethn Migr Stud, 32(5), 743–764.

Light, I., & Gold, J. S. (2000). Ethnic economies. UK: Academic.

Lin, X., & Tao, S. (2012). Transnational entrepreneurs: characteristics, drivers, and success factors. J Int Entrep, 10(1), 50–69.

Loscocco, K., & Smith-Hunter, A. (2004). Women home-based business owners: insights from comparative analysis. Women Manage Rev, 19(3), 164–173.

Mason, C. (2009–2010). Home-based businesses: Challenging their Cinderella status. Small Enterp Res, 17(2), 104–111.

Mason, C. M., Carter, S., & Tagg, S. (2011). Invisible businesses: the characteristics of home-based businesses in the united kingdom. Reg Stud, 45(5), 625–639.

McMullen, J. S., & Dimov, D. (2013). Time and the entrepreneurial journey: the problems and promise of studying entrepreneurship as a process. J Manag Stud, 50(8), 1481–1512.

Miles, M., & Huberman, M. (1984). Qualitative data analysis: a sourcebook of new methods. CA: Sage.

Morrish, S. C., Miles, M. P., & Deacon, J. H. (2010). Entrepreneurial marketing: acknowledging the entrepreneur and customer-centric interrelationship. J Strateg Mark, 18(4), 303–316.

Nansen, B., Arnold, M., Gibbs, M., & Davis, H. (2010). Time, space and technology in the working-home: an unsettled nexus, New technology. Work Employ, 25(2), 136–153.

Pretorius, M., Millard, S. M., & Kruger, M. E. (2005). Creativity, innovation and implementation: management experience, venture size, life cycle stage, race and gender as moderators. S Afr J Bus Manage, 36(4), 55–68.

Price, M., & Chacko, E. (2009). The mixed embeddedness of ethnic entrepreneurs in a new immigrant gateway. J Immigrant & Refug Stud, 7(3), 328–346.

Punch, K. F. (2005). Introduction to social research: qualitative and quantitative approaches. London: Sage.

Ram, M., & Jones, T. (2008). Ethnic-minority businesses in the UK: a review of research and policy developments. Eviron Plann C Gov Policy, 26(2), 352–374.

Ram, M., & Smallbone, D. (2001). Ethnic enterprise: policy in practice. Report prepared for the Small Business Service.

Ramsden, P. (2008). Out of the ashes: supporting specialist projects for minority ethnic entrepreneurs – the experience of the UK phoenix fund programme”. In C. R. Oliveira & J. Rath (Eds.), Migrações journal - special issue on immigrant entrepreneurship (pp. 207–228). Lisbon: ACIDI.

Rath, J. (2002). A quintessential immigrant niche? the non-case of immigrants in the Dutch construction industry. Entrep Reg Dev, 14(4), 355–372.

Richards, L. (2005). Handling qualitative data: a pracical guide. London: Sage Publications.

Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Acad Manag Rev, 26(2), 243–263.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. Acad Manag Rev, 25(1), 217–226.

Shin, J. (2014). New business model creation through the triple helix of young entrepreneurs, SNSs, and smart devices. Int J Technol Manag, 66(4), 302–318.

Simpson, E. (2014). Self-employment? first choice or last resort. BBC news, June 11 th 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-27397993. Accessed 19 June 2014.

Smith, J. W., & Calasanti, T. (2005). The influences of gender, race and ethnicity on workplace experiences of institutional and social isolation: an exploratory study of university faculty. Sociol Spectr, 25(3), 307–334.

Smith, J. W., & Markham, E. (1998). Dual construct of isolation: institutional and social forms. Strategic Organ Leadersh J, 2(2), 51–66.

Smith, R., McElwee, G., McDonald, S., & Dodd, S. D. (2013). Qualitative entrepreneurship authorship: antecedents, processes and consequences. Int J Entrep Behav Res, 19(4), 364–386.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990). Basics of qualitative research. CA: Sage.

Suddaby, R., Bruton, G. D., & Si, S. X. (2015). Entrepreneurship through a qualitative lens: insights on the construction and/or discovery of entrepreneurial opportunity. J Bus Ventur, 30(1), 1–10.

Sulaiman, R., Shariff, S. S. M., & Ahmad, M. S. (2009). The e-business potential for home-based businesses in Malaysia: a qualitative study. Int J Cyber Soc Educ, 2(1), 21–36.

Trupp, A. (2015). Agency, social capital, and mixed embeddedness among akha ethnic minority street vendors in Thailand's tourist areas. SOJOURN: J Soc Issues SE Asia, 30(3), 780–818.

UK Borders Agency. (2014). https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/325888/t1_E_guidance_07_14.pdf. Accessed 2 July 2014.

Van Vianen, A. E. M. (2000). Person-organization fit: the match between newcomers’ and recruiters’ preferences for organizational cultures. Pers Psychol, 53(1), 113–149.

Van Wyk, R., & Boshoff, A. B. (2004). Entrepreneurial attitudes. S Afr J Bus Manage, 35(2), 33–38.

Volery, T. (2007). Ethnic entrepreneurship: a theoretical framework. In L.-P. Dana (Ed.), Handbook of research on ethnic entrepreneurship: a coevolutionary view on resource management. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Walker, E., & Webster, B. (2004). Gender issues in home-based businesses. Women Manage Rev, 19(8), 404–412.

Weick, K. E. (2007). The generative properties of richness. Acad Manag J, 50(1), 14–19.

Zhang, H., Lu, Y., Gao, P., & Chen, Z. (2014). Social shopping communities as an emerging business model of youth entrepreneurship: exploring the effects of website characteristics. Int J Technol Manag, 66(4), 319–345.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the SAMS (Society for the Advancement of Management Studies), UKCES (UK Commission for Employment Skills) and ESRC (Economic and Social Research Council), UK (Reference: ES/L002701/1) to provide the funds for their research and to fund the first author.

Authors’ contributions

Both the authors have been involved in recruiting and interviewing the research participants, and both of them have contributed to writing as well. Both authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Anwar, M.N., Daniel, E.M. Ethnic entrepreneurs and online home-based businesses: an exploratory study. J Glob Entrepr Res 7, 6 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-017-0065-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-017-0065-3