- Research

- Open access

- Published:

Socio-cultural beliefs and perceptions influencing diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women in Ghana: a systematic review

BMC Women's Health volume 24, Article number: 288 (2024)

Abstract

Background

Breast cancer is currently the most commonly diagnosed cancer in Ghana and the leading cause of cancer mortality among women. Few published empirical evidence exist on cultural beliefs and perceptions about breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Ghana. This systematic review sought to map evidence on the socio-cultural beliefs and perceptions influencing the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among Ghanaian women.

Methods

This review was conducted following the methodological guideline of Joanna Briggs Institute and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses. The literature search was conducted in PubMed, CINAHL via EBSCOhost, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Embase. Studies that were conducted on cultural, religious, and spiritual beliefs were included. The included studies were screened by title, abstract, and full text by three reviewers. Data were charted and results were presented in a narrative synthesis form.

Results

After the title, abstract, and full-text screening, 15 studies were included. Three categories were identified after the synthesis of the charted data. The categories included: cultural, religious and spiritual beliefs and misconceptions about breast cancer. The cultural beliefs included ancestral punishment and curses from the gods for wrongdoing leading to breast cancer. Spiritual beliefs about breast cancer were attributed to spiritual or supernatural forces. People had the religious belief that breast cancer is a test from God and they resorted to prayers for healing. Some women perceived that breast cancer is caused by spider bites, heredity, extreme stress, trauma, infections, diet, or lifestyle.

Conclusion

This study adduces evidence of the socio-cultural beliefs that impact on the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women in Ghana. Taking into consideration the diverse cultural and traditional beliefs about breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, there is a compelling need to intensify nationwide public education on breast cancer to clarify the myths and misconceptions about the disease. We recommend the need to incorporate socio-cultural factors influencing breast cancer diagnosis and treatment into breast cancer awareness programs, education, and interventions in Ghana.

Introduction

Breast cancer is a global public health concern due to its increasing incidence coupled with the high mortality rate among women in low- and high-income countries [1]. In 2020, it was estimated that 2.3 million breast cancer cases were newly diagnosed with approximately 685,000 deaths globally [1]. In Ghana, breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality among women [2]. In 2020, breast cancer accounted for approximately 31.8% of all cancer cases in Ghana [3].

Evidence shows that cultural factors such as conceptualizations of health, illness, beliefs, and values influence breast cancer screening among women in certain populations [4,5,6]. Breast cancer screening is reported to be relatively low among women living in Ghana. A nationwide study revealed that only 4.5% of Ghanaian women aged 50 years and older had undergone mammography screening [7]. The low levels of breast cancer screening lead to undetected breast cancer symptoms, contributing to the late-stage diagnosis of breast cancer and subsequent poorer outcomes and mortality [8]. There have been low levels of awareness and knowledge about breast cancer among women in Ghana [9]. Also, there is a lack of understanding of the perceptions and beliefs toward breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Ghana.

Culture is considered a multidimensional set of shared beliefs and socially transmitted ideologies about the world, which are passed on from generation to generation [10, 11]. Cultural beliefs within certain communities across the globe are considered a determinant of health risk perceptions and behaviors in promoting or seeking health care in diverse populations [12]. In traditional Ghanaian communities, good health is recognized as a suitable relationship between the living and the dead and being in harmony with the individuals’ environment. Thus, disease is conceptualized as a malfunctioning of the body system which is probably due to a lack of harmony with supernatural/ancestral forces [13]. This belief influences how diseases are treated and the steps taken to manage the disease and ultimately how the disease is experienced [13, 14]. Cultural beliefs connected to breast cancer are among the key determinants in women’s decision-making regarding breast cancer screening practices in traditional societies [14, 15]. In most Ghanaian communities, breast cancer is believed to be associated with supernatural powers, hence, women seek alternative treatments (healing/prayer camps) first and only report to health facilities in advanced stages of breast cancer [16].

It is therefore important to consider how socio-cultural factors impact breast cancer diagnosis and treatment because these factors influence cancer care in resource-limited settings. To the best of our knowledge, no review has been conducted in Ghana specifically to address the cultural, religious, and spiritual beliefs influencing timely diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women. To fill this gap, this systematic review sought to map evidence on the cultural beliefs and perceptions that influence the timely diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the updated methodological guideline of Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [17, 18] and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. The updated JBI methodological guidance regarding conducting a mixed methods systematic review recommends that reviewers use a convergent approach to synthesize and integrate both qualitative and quantitative studies [18]. Therefore, using a mixed methods systematic review involving both quantitative and qualitative studies was deemed the most appropriate study design because this is the first evidence synthesis on the cultural, religious, and spiritual beliefs that influence breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Ghana.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

-

Studies conducted among women and explored the cultural beliefs and perceptions about breast cancer were included.

-

Studies that were only limited to Ghanaian communities were included.

-

Empirical studies published in peer-review journals.

-

Observational studies, using qualitative and/or quantitative methods were also included.

-

The exclusion criteria involved review studies, conference papers, editorials and abstracts.

-

Studies published before 2012 were also excluded.

Search strategy

This review adopted the triple-step search strategy proposed by the JBI for all types of reviews [19]. The first step involved an initial limited search in PubMed for already existing published research articles on sociocultural beliefs and perceptions about breast cancer in Ghana. The initial limited search ensured the identification of relevant keywords used in developing the preliminary search terms. Step two involved a formal search after finalizing and combining the following keywords (‘breast cancer’, ‘cultural beliefs’, ‘religious beliefs’, ‘traditional beliefs’, ‘perception’, and ‘Ghana’) using Boolean operators. A comprehensive search was conducted in PubMed, CINAHL via EBSCOhost, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Embase from 2012–2022. The final step involved manual tracing of the reference list of studies for additional studies. This was done up to the point of saturation where no new information emanated from the subsequent manual search of articles.

Study selection

Following the searches, the identified records were exported into EndNote 2020 reference manager for duplicate removal. After the duplicate removal, the reviewers ensured consistency in screening through the following process: (1) joint screening by two reviewers was conducted until they felt confident to start independent screening, (2) independent blinded screening of titles/abstracts followed by a meeting and discussion of discrepancies and (3) repetition of step 2 until an acceptable agreement was met. Following the screening of the titles/abstracts, full-text review was conducted following a two-step process. The first step involved two reviewers who screened all the articles identified after the title/abstract screening. Thereafter, two independent reviewers assessed the full-text articles for inclusion or exclusion. In the course of the full-text screening, any disagreements that emerged were discussed for consensus. Throughout the screening of the abstracts, full-texts, and data extraction, the reviewers regularly met to discuss and solve emerging issues.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed in line with the aim of this review. Two authors independently extracted the relevant information from the included articles. The following information was extracted from the articles: first author’s name, year of publication, study location, study type, aim, study population, and key findings. Disagreements during the data extraction process were resolved by a discussion and where a resolution was not reachable, the last author resolved it through further adjudication. Study selection and data extraction were conducted manually.

Data analysis

A convergent integrated approach [20] was employed to transform the data into narrative form because the extracted information was from quantitative and qualitative studies. The analysis followed JBI recommendation where we qualitized quantitative data for data transformation because this is less prone to error when codified than when qualitative data is given numerical values. Qualitizing entails taking data from quantitative studies, translating or converting it into textual descriptions so that it can be integrated with qualitative data, and providing a narrative interpretation of the quantitative results [18]. Following the convergent synthesis of the transformed data, the reviewers undertook repeated, detailed examination of the assembled data to identify categories on the basis of similarity in meaning [18]. Out of these, three categories were derived from the analysis.

Assessment of methodological quality

Using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018, two researchers (AA and RAA) evaluated each included study’s quality separately [21]. After discussing disagreements between the two reviewers (AA and RAA), BOA helped to forge a consensus. Methodological quality standards for evaluating research using mixed methodologies, quantitative, and qualitative approaches are included in the MMAT. The MMAT assesses the suitability of the research objective, study design, technique, participant recruitment, data collection, data analysis, results presentation, author comments, and conclusions. Hong et al. [21] discourages the overall quality scoring of the included studies, therefore, the methodological quality of the studies was evaluated using the recommended guidelines.

Results

Literature search

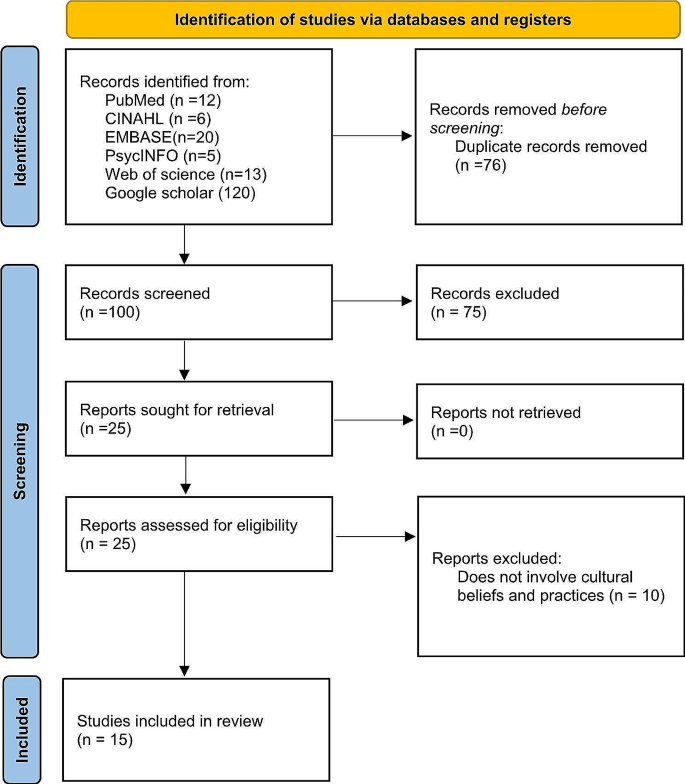

Our search yielded a total of 176 records from the electronic databases. After duplicates were automatically removed through the EndNote (n = 76), 100 records were reviewed independently by two authors based on the title and abstract. Records that did not meet the inclusion (n = 75) were removed after holding discussions to identify discrepancies in the review process. Thereafter, full texts of the remaining 25 articles were assessed for eligibility. Hand-search of the included study references yielded no results. In total, we included 15 studies [22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The article selection process is shown in the PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1).

Characteristics of the included studies and quality

The majority of the studies [22,23,24, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35] were conducted in the southern part of Ghana where there are better health infrastructures compared to the northern part of Ghana. Eight of the included studies were qualitative while the rest employed quantitative study designs. The summary of the characteristics of the 15 studies is shown in Table 1. The appraisal of the included studies was assessed using the MMAT. All the studies were included, and none were excluded due to poor methodological quality. All 15 studies met the screening criteria and provided clear research questions. The studies included clearly stated and described research design, and target population, and used appropriate measurements.

Cultural beliefs

Breast cancer is believed by some sections of Ghanaians to be a curse or a punishment from the lesser gods for sins committed by the individual [22]. Some women believed that an extra-marital immoral lifestyle provokes God’s retribution for breast cancer development [29]. Some people believed that it is an ancestral punishment for the woman’s refusal to give birth in order to continue the ancestral lineage [23] and because of this, they are given spiritual babies to suckle the breast which then causes cancer [23]. It is also believed some women have been pronounced cursed due to some wrongdoings [25]. Due to the cultural belief, some women prayed to their ancestors so that traditional medicine will heal them of the breast cancer [26].

“…when it started, my uncles came to my aid, they took me to the village to see a “Tim Lana” (referring to a traditional healer). He was very good. He told me everything about my problem. So, there was no need for visiting the hospital…” [36].

Spiritual and religious beliefs

Some studies in Greater Accra, Tamale, and Kumasi indicated that breast cancer was a spiritual attack from humans or family members that sought to kill them while some believe it emanated from evil forces [29, 31, 36]. Participants in some studies indicated that breast cancer is attributed to some spiritual or supernatural forces [32, 33, 36] and can only be cured through spiritual means [33]. Due to the spiritual beliefs, some women went to traditional healers for treatment [26, 36]. A study in the northern part of Ghana revealed that women who suffer from breast cancer are witches and have used their breasts for ritual purposes [25] while in the southern part of Ghana some participants believed that breast cancer is caused by witches [22]. For example, a narration from a participant stated:

“I believe my condition is spiritual and I realized it is coming from my mother’s side” [31].

“The problem is that my disease is a spiritual attack, so it has to be treated spiritually; the hospital drugs cannot get this out of me…” [36].

Some studies in the southern and northern part of Ghana stated that participants had a religious belief that the disease was a test from God and resulted in prayers for healing [31, 36] and also believed that God had the supernatural powers to miraculously melt the breast lump [29, 32] and completely cure them [32]. Some women also believed that it was their fate to get breast cancer [36]. Due to these religious beliefs some women had to resort to prayer camps for healing which leads to delay in diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer [26].

Misconceptions about breast cancer

Some women perceived that breast cancer is caused by spider bites [24], heredity, extreme stress [22, 32], trauma, infections [22], diet, or lifestyle [22, 35]. Some perceived risk factors of breast cancer as stated by some women included non-breastfeeding women, obesity, or overweight [25, 30, 33], and contraceptive use [30]. Some women had the perception that male health practitioners would not be allowed to examine or see their breasts while some preferred male doctors to examine their breasts [27]. A study in Accra conducted among female nonmedical students revealed that suckling the breast by a male caused breast cancer [28]. It is also perceived that putting money in the brassieres could be a possible cause of breast cancer among females [23, 35]. A study by Iddrisu et al. [31] and Agbokey [23] revealed that breast cancer is a disgraceful disease, dangerous, and a fast killer. Some people also believed that breast cancer can be cured [27, 32] by herbal treatment or medicine [25] while some believed that it is not curable [27]. Some people also believed that breast cancer was contagious and transmissible and avoided sharing equipment with breast cancer survivors [31]. A breast cancer survivor narrated:

“…my mum believes the disease can be transmitted so she does not allow me to eat with my son. I have separate bowls, spoons, and cups from that of the family…” [31].

Discussion

This study reviews the existing literature on socio-cultural beliefs influencing the timely diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women, and this revealed diverse cultural, spiritual, and religious beliefs across the regions of Ghana. The current findings emphasize critical issues that lead to misguidance and share ignorance about breast cancer and its treatment among a section of Ghanaian communities which is rooted in their personal beliefs. Cultural beliefs are key in the decision-making process for the treatment of ailments depending on their knowledge level about the condition. This could probably lead to making the right decision or the wrong treatment decision. The diverse cultural, spiritual, and religious beliefs about breast cancer could affect the health seeking behavior of women diagnosed with breast cancer within the Ghanaian communities.

Consistent with a systematic review findings [13] it is believed that breast cancer emanates as a result of supernatural forces, curses, and punishment from lesser gods/ancestors for wrongdoings. Though not all Africans hold this traditional belief in ancestral spirits, some believe that health and illness are in the hands of a higher power such as God or Allah [13]. Hence, in most African communities it is common practice to seek traditional medicine for the treatment of diseases which is in line with their beliefs [37]. Due to the cultural/traditional belief systems and practices, most women report to health facilities with advanced stages of breast cancer which adversely impacts the breast cancer diagnosis and treatment [36]. Most women resort to traditional or spiritual healing because this method of treatment combines body, soul, and spirit. In some African settings, traditional healers are trusted to treat diseases including cancer because women believe they look for both scientific and metaphysical causes of the disease. It is possible that breast cancer patients who combine both traditional and modern methods of treatment may experience treatment interference. This dual approach can impact treatment effectiveness and lead to adverse effects or complications. The provision of culturally sensitive care by recognizing unique cultural, religious, and social beliefs and practices is of paramount importance for early detection and treatment of breast cancer among women [38,39,40]. Globally, women’s cultural beliefs and perceptions towards breast cancer should be examined to optimize timely breast cancer diagnosis and treatment.

Religious fanaticism coupled with lack of knowledge about the disease condition could impede the utilization of medical treatment, especially when religious beliefs impact negatively on people’s health-seeking behaviors [36]. A study in Nigeria revealed that religious beliefs about breast cancer were observed to be a barrier to breast cancer screening among women [41]. This review found that some women in the southern part of Ghana believed that breast cancer was a test from God and resorted to prayers because they believed that God had supernatural powers to heal them from the disease. Though religious beliefs are considered to be a source of spiritual strength and help people to cope with the disease, the religious misconceptions, and mistaken beliefs are thought to contribute to delayed heath-seeking attitudes and lack of breast cancer screening among women [42]. In the current review, it was reported that some women stayed in prayer camps for almost one year seeking healing and later reported to health facilities with advanced breast cancer which has dire consequences on the survival rate of women. Efforts to sensitize women and religious leaders about the early presentation of breast disease to health facilities for diagnosis and treatment would be key to reduce the number of breast cancer cases detained in religious camps. It is also imperative for religious bodies to discuss health related issues including breast cancer to create much awareness about the condition.

This review identified varied perceptions of breast cancer where breast cancer has been attributed to spider bites and putting money in the brassieres among others. Some believed that breast cancer was a contagious and transmissible disease. These findings show poor knowledge level among women concerning breast cancer. Even though in this review most women had heard or were aware of breast cancer, the varied perceptions about breast cancer suggests low knowledge level of breast cancer. The low knowledge level of breast cancer among women have been associated with late presentation of breast cancer to health facilities [40]. Women presenting to health facilities with advanced stage breast cancer have been associated with low survival rate in the African region as compared to high income countries [43]. A study conducted in Ghana revealed that the breast cancer survival rate among women was below 50% which was probably due to late presentation and lack of breast cancer screening [44]. We recommend intensification of public health education campaigns on breast cancer in order to improve women’s knowledge of the disease which will subsequently enhance early presentation, diagnosis, and treatment.

Implication for policy and practice

Metaphors such as spider bites, supernatural forces, witchcraft, and many other beliefs are associated with breast cancer in Ghana which impact the understanding of the disease and whether or not to seek medical treatment. Therefore, culturally sensitive intervention programs targeted at improving breast cancer awareness among women, religious and traditional leaders are imperative. These intervention programs could entail community engagement, workshops, or educational materials tailored to address specific cultural beliefs and misconceptions.

Taking into consideration the diverse cultural beliefs about breast cancer, there is a compelling need for nationwide public education on breast cancer to clarify the myths and misconceptions about the disease. The education program should be culturally tailored to address the myths and misconceptions. It is important that considerations are given to these issues, not only focusing on how these issues affect women’s lives post-treatment but also on how these issues can be resolved to improve diagnosis and treatment of the disease. We recommend that socio-cultural factors influencing breast cancer diagnosis and treatment should be incorporated into breast cancer awareness programs, education, and intervention programs in Ghana. We believe these would help inform women and encourage them to report to health facilities early with breast cancer symptoms to initiate timely diagnosis and treatment to improve the outcomes of the disease in Ghana.

Further research is required to explore appropriate and effective multidimensional culturally sensitive intervention research that integrates cultural beliefs and breast cancer treatment especially, in different Ghanaian communities.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has several strengths, one major strength is the extensive and comprehensive search in various electronic databases following the methodological guideline of JBI and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines. Also, the inclusion of both qualitative and quantitative studies, allowed for a more comprehensive understanding of the socio-cultural beliefs influencing breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Ghana.

The review considered only published studies and possibly may have overlooked unpublished or gray literature that could contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. Most of the studies were concentrated in the southern part of Ghana and therefore the results might not represent all the regions in Ghana.

Conclusion

This study adduces evidence on the socio-cultural beliefs that impact diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women in Ghana. As policy makers, clinicians and other stakeholders strive to improve breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, there is a need to address the socio-cultural beliefs to improve breast cancer outcomes in Ghana and potentially reduce breast cancer-related mortality.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Afaya A, Seidu AA, Sang S, Yakong VN, Afaya RA, Shin J, Ahinkorah BO. Mapping evidence on knowledge of breast cancer screening and its uptake among women in Ghana: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):526.

International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory. 2021:https://gco.iarc.fr/.

Donnelly TT, Al Khater A-H, Al-Bader SB, Al Kuwari MG, Al-Meer N, Malik M, Singh R, Chaudhry S, Fung T. Beliefs and attitudes about breast cancer and screening practices among arab women living in Qatar: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2013;13(1):1–16.

Pasick RJ, Burke NJ. A critical review of theory in breast cancer screening promotion across cultures. Annu Rev Public Health. 2008;29:351–68.

Azaiza F, Cohen M. Between traditional and modern perceptions of breast and cervical cancer screenings: a qualitative study of arab women in Israel. Psychooncology. 2008;17(1):34–41.

Agyemang AF, Tei-Muno AN, Dzomeku VM, Nakua EK, Duodu PA, Duah HO, Bentil AB, Agbadi P. The prevalence and predictive factors of breast cancer screening among older Ghanaian women. Heliyon. 2020;6(4):e03838.

Rivera-Franco MM, Leon-Rodriguez E. Delays in breast Cancer detection and treatment in developing countries. Breast Cancer (Auckl). 2018;12:1178223417752677.

Boamah Mensah AB, Mensah KB, Aborigo RA, Bangalee V, Oosthuizen F, Kugbey N, Clegg-Lamptey JN, Virnig B, Kulasingam S, Ncama BP. Breast cancer screening pathways in Ghana: applying an exploratory single case study methodology with cross-case analysis. Heliyon. 2022;8(11):e11413.

d’Andrade RG, Strauss C. Human motives and cultural models. Volume 1. Cambridge University Press; 1992.

Koltko-Rivera ME. The psychology of worldviews. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(1):3–58.

Iwelunmor J, Newsome V, Airhihenbuwa CO. Framing the impact of culture on health: a systematic review of the PEN-3 cultural model and its application in public health research and interventions. Ethn Health. 2014;19(1):20–46.

White P. The concept of diseases and health care in African traditional religion in Ghana. HTS: Theological Stud. 2015;71(3):1–7.

Tetteh DA, Faulkner SL. Sociocultural factors and breast cancer in sub-saharan Africa: implications for diagnosis and management. Womens Health (Lond). 2016;12(1):147–56.

Kim JG, Hong HC, Lee H, Ferrans CE, Kim EM. Cultural beliefs about breast cancer in Vietnamese women. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):74.

Clegg-Lamptey JN, Dakubo JC, Attobra YN. Psychosocial aspects of breast cancer treatment in Accra, Ghana. East Afr Med J. 2009;86(7):348–53.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Khalil H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Synth. 2020;18(10):2119–26.

Stern C, Lizarondo L, Carrier J, Godfrey C, Rieger K, Salmond S, Apóstolo J, Kirkpatrick P, Loveday H. Methodological guidance for the conduct of mixed methods systematic reviews. JBI Evid Synthesis. 2020;18(10):2108–18.

Peters MD, Godfrey CM, McInerney P, Soares CB, Khalil H, Parker D. The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2015: methodology for JBI scoping reviews. 2015.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Bujold M, Wassef M. Convergent and sequential synthesis designs: implications for conducting and reporting systematic reviews of qualitative and quantitative evidence. Syst Rev. 2017;6(1):61.

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, Gagnon M-P, Griffiths F, Nicolau B. Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018. Registration Copyr 2018, 1148552(10).

Addae-Korankye A, Abada A, Imoro F. Assessment of breast cancer awareness in Tamale Metropolis in Ghana. World Sci Res. 2014;3(1):1–5.

Agbokey F. Health seeking behaviours for breast cancer among breast cancer patients at the Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital. Kumasi, Ghana: University of Ghana; 2014.

Agbokey F, Kudzawu E, Dzodzomenyo M, Ae-Ngibise KA, Owusu-Agyei S, Asante KP. Knowledge and Health Seeking Behaviour of Breast Cancer Patients in Ghana. Int J Breast Cancer 2019, 2019:5239840.

Asobayire A, Barley R. Women’s cultural perceptions and attitudes towards breast cancer: Northern Ghana. Health Promot Int. 2015;30(3):647–57.

Asoogo C, Duma SE. Factors contributing to late breast cancer presentation for health care amongst women in Kumasi, Ghana. Curationis 2015, 38(1).

Azumah FD, Onzaberigu NJ. Community knowledge, perception and attitude toward breast cancer in Sekyere East District Ghana. Int J Innov Educ Res. 2017;5(6):221–35.

Boafo IM, Tetteh PM. Self-efficacy and perceived barriers as determinants of breast self-examination among female nonmedical students of the University of Ghana. Int Q Community Health Educ. 2020;40(4):289–97.

Bonsu AB, Ncama BP. Recognizing and appraising symptoms of breast cancer as a reason for delayed presentation in Ghanaian women: a qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(1):e0208773.

Dadzi R, Adam A. Assessment of knowledge and practice of breast self-examination among reproductive age women in Akatsi South district of Volta region of Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(12):e0226925.

Iddrisu M, Aziato L, Ohene LA. Socioeconomic impact of breast cancer on young women in Ghana: a qualitative study. Nurs Open. 2021;8(1):29–38.

Kugbey N, Oppong Asante K, Meyer-Weitz A. Illness perception and coping among women living with breast cancer in Ghana: an exploratory qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e033019.

Opoku SY, Benwell M, Yarney J. Knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, behaviour and breast cancer screening practices in Ghana, West Africa. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;11:28.

Osei E, Osei Afriyie S, Oppong S, Ampofo E, Amu H. Perceived breast Cancer risk among female undergraduate students in Ghana: a cross-sectional study. J Oncol. 2021;2021:8811353.

Osei-Afriyie S, Addae AK, Oppong S, Amu H, Ampofo E, Osei E. Breast cancer awareness, risk factors and screening practices among future health professionals in Ghana: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(6):e0253373.

Salisu WJ, Mirlashari J, Seylani K, Varaei S, Thorne S. Fatalism, distrust, and breast cancer treatment refusal in Ghana. Can Oncol Nurs J. 2022;32(2):198–205.

Omonzejele PF. African concepts of health, disease, and treatment: an ethical inquiry. Explore (NY). 2008;4(2):120–6.

Wright SV. An investigation into the causes of absconding among black African breast cancer patients. S Afr Med J. 1997;87(11):1540–3.

Benedict AO. The perception of illness in traditional Africa and the development of traditional medical practice. Int J Nurs. 2014;1(1):51–9.

Afaya A, Ramazanu S, Bolarinwa OA, Yakong VN, Afaya RA, Aboagye RG, Daniels-Donkor SS, Yahaya AR, Shin J, Dzomeku VM, et al. Health system barriers influencing timely breast cancer diagnosis and treatment among women in low and middle-income Asian countries: evidence from a mixed-methods systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):1601.

Elewonibi B, BeLue R. The influence of socio-cultural factors on breast cancer screening behaviors in Lagos, Nigeria. Ethn Health. 2019;24(5):544–59.

Saeed S, Asim M, Sohail MM. Fears and barriers: problems in breast cancer diagnosis and treatment in Pakistan. BMC Womens Health. 2021;21(1):151.

Anyigba CA, Awandare GA, Paemka L. Breast cancer in sub-saharan Africa: the current state and uncertain future. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2021;246(12):1377–87.

Mensah S, Dogbe J, Kyei I, Addofoh N, Paintsil V, Osei T. Determinants of late presentation and histologic types of breast cancer in women presenting at a Teaching Hospital in Kumasi. Ghana J Cancer Prev Curr Res. 2015;3(4):00089.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The author did not receive any funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AA, and EAA conceived the study, analyzed and wrote the methods section. AA, VB and RAA conducted the literature search and wrote the background. AA, RAA, and RY screened the included articles and extracted the data. AA, AS and BOA conducted literature search and discussed the results. All the authors reviewed and provided intellectual content and modification. All the authors reviewed and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

This study did not require ethical approval.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Afaya, A., Anaba, E.A., Bam, V. et al. Socio-cultural beliefs and perceptions influencing diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer among women in Ghana: a systematic review. BMC Women's Health 24, 288 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03106-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03106-y