Abstract

Background

Biological therapies are increasingly common in the United States. Although their clinical development may deviate significantly from the classic paradigm used for small molecule drugs, there has been little systematic analysis of these programs. We describe the development programs and factors associated with approval in the first review cycle for biologics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (FDA CDER) between 2003 and 2016.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis of publicly available approval packages including clinical pharmacology/biopharmaceutics, medical and summary reviews, and approval letters for biologics approved by FDA CDER. We evaluated characteristics of the development program (eg, use of expedited pathways, clinical pharmacology studies, number and type of pivotal trials) and the prevalence and correlates of first cycle approval, a key indicator of successful product development.

Results

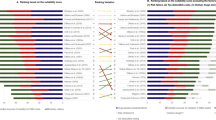

We assessed 81 development programs for 75 unique therapies. Most programs (67%) made use of at least 1 expedited designation and about half (49%) were designated as orphan products. The clinical pharmacology programs were highly variable and one in four (25%) did not include an ascending dose study, where the tolerability of the therapeutic is typically determined before pivotal trials. Since 2003, an increasing proportion of biologics have been approved on first cycle approval and with fewer than 2 pivotal clinical trials (P < .001 for trend). Of the approximately three-fourths (76%) of products that were approved on the first review cycle, the likelihood of such approval was greater among development programs that performed an ascending dose study (84% vs 55%, P = .01) or held an End of Phase 2 meeting (85% vs 57%, P = .01).

Conclusion

Considerable regulatory flexibility, with respect to the number of pivotal trials and data supporting dosing, coincides with a growing number of biologics approved on an annual basis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

US Food and Drug Administration New Molecular Entity (NME) Drug and New Biologic Approvals. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DevelopmentApprovalProcess/HowDrugsareDevelopedandApproved/DrugandBiologicApprovalReports/NDAandBLAApprovalReports/ucm373420.htm. Published September 1, 2015. Accessed January 6, 2017.

Philippidis A. The top 15 best-selling drugs of 2016. Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. https://www.genengnews.com/the-lists/the-top-15-best-selling-drugs-of-2016/77900868. Published March 2, 2017. Accessed December 24, 2017.

Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, et al. Regulatory review of novel therapeutics—comparison of three regulatory agencies. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(24):7.

Downing NS, Aminawung JA, Shah ND, Krumholz HM, Ross JS. Clinical trial evidence supporting FDA approval of novel therapeutic agents, 2005-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(4):368-377.

Ogasawara K, Breder CD, Lin DH, Alexander GC. Exposure- and dose-response analyses in dose selection and labeling of FDA-approved biologics. Clin Ther. 2018;40(1):95-102.e2.

Zineh I, Woodcock J. Clinical pharmacology and the catalysis of regulatory science: opportunities for the advancement of drug development and evaluation. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2013;93(6): 515–525.

Tabor E. Food and Drug Administration requirements for clinical studies in pediatric patients. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science. 2015;49(5):7.

Zuckerman R. A new mechanism for tracking publicly available study volunteer demographics. Drug Inform J. 2011;45:10.

Sasinowski FJ, Panico EB, Valentine JE. Quantum of effectiveness evidence in FDA’s approval of orphan drugs. Therapeutic Innovation & Regulatory Science. 2015;49(5):680–697.

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Providing Clinical Evidence of Effectiveness for Human Drug and Biological Products. Rockville, MD: HHS, 1998.

Ishibashi T, Kusama M, Sugiyama H. Analysis of regulatory review times of new drugs in Japan: association with characteristics of new drug applications, regulatory agency, and pharmaceutical companies. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37:7.

McGauran N, Wieseler B, Kreis J, Schüler YB, Kölsch H, Kaiser T. Reporting bias in medical research—a narrative review. Trials. 2010;11:37.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alexander, G.C., Ogasawara, K., Wiegand, D. et al. Clinical Development of Biologics Approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, 2003-2016. Ther Innov Regul Sci 53, 752–758 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1177/2168479018812058

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/2168479018812058