Abstract

HMX can be detonated by an exploding bridgewire (EBW) or a slapper. Direct HMX detonation by an electrical arc has not been demonstrated. This paper shows that the shock from a 99% worst-case lightning current (200 kA and 500 ns rise time) can detonate standard-density HMX at elevated temperatures (i.e., HMX in the most sensitive \(\delta\)-phase at a temperature above 177°C) and that the shock from a 200-kA peak current pulse with a 100 ns rise time can detonate HMX at ambient temperatures. Two necessary detonation conditions are used for these assertions. The relevant Pop-Plot for HMX is converted into an empirical detonation criterion, which is applicable to explosives subject to shocks of variable pressure. The minimum detonation spot size for detonation reported in the literature is used as the other condition. PBX-9501 and LX-04 have similar Pop-Plots to those of HMX; thus, the HMX result is directly applicable. Although PBX-9404 and PBX-9407 are HMX-based, they have somewhat lower Pop-Plot pressures than HMX and are more sensitive to shocks caused by electrical arcs than HMX. As the HMX thermal conductivity is low and the phase transition can be slow, the chance of having a sufficient amount of HMX converted to \(\delta\)-HMX during an accident is small; therefore, the threat of lightning shock-detonating HMX is very low. We recommend lightning simulation tests to be conducted for \(\delta\)-HMX. We also would like to point out that a lightning can ignite HMX, which, in turn, leads to detonation via the deflagration-to-detonation transition.

Similar content being viewed by others

REFERENCES

K. C. Chen, L. K. Warne, R. E. Jorgenson, and J. H. Niederhaus, “TATB Sensitivity to Shocks from Electrical Arcs," Propell., Explos., Pyrotech. 44 (7), 1000–1009 (2019); DOI: 10.1002/prep.201800286.

LASL Explosive Property Data, Ed. by T. R. Gibbs and A. Popolato (Univ. of California Press, 1980).

B. W. Asay, Shock Wave Science and Technology Reference Library, Vol. 5: Non-Shock Initiation of Explosives (Springer, 2010).

N. Griffiths and J. M. Groocock, “The Burning to Detonation of Solid Explosives," J. Chem. Soc., Article No. 814, 4154–4162 (1960).

“LLNL Explosives Reference Guide," LLNL-WEB-758418 (2018).

B. F. Henson, L. Smilowitz, B. W. Asay, and P. M. Dickson, “The \(\beta\)–\(\delta\) Phase Transition in the Energetic Nitramine Octahydro-1,3,5,7-tetranitro-1,3,5,7-tetrazocine: Thermodynamics," J. Chem. Phys. 117 (8), 3780–3788 (2002); DOI: 10.1063/1.1495399.

S. I. Braginskii, “Theory of the Development of a Spark Channel," Zh. Exp. Teor. Fiz. 34 (6) 1548–1557 (1958).

Y. T. Lee and R. M. More, “An Electron Conductivity Model for Dense Plasmas," Phys. Fluids 27 (5), 1273–1286 (1984); DOI: 10.1063/1.864744.

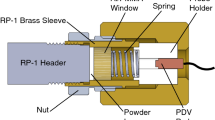

K. C. Chen and L. K. Warne, “PETN Spark-Gap Detonators," J. Energ. Mater. (2020); DOI: 10.1080/07370652.2020.1956986.

T. J. Tucker, J. E. Kennedy, and D. L. Allensworth, “Secondary Explosive Spark Detonators," in 7th Symp. on Explosives and Pyrotechnics, Franklin Inst., September 8–9, 1971.

L. K. Warne, R. E. Jorgenson, and J. M. Lehr, “Resistance of a Water Spark," SAND2005-6994 (2005); DOI: 10.1080/07370652.2020.1956986.

T. A. Brunner, K. R. Cochrane, C. J. Garasi, et al., “ALEGRA-MHDP: Version 4.6," SAND2004-5996 (2004).

G. B. Whitham, Linear and Nonlinear Waves (John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1974), pp. 191–192.

J. Lee Richard, “Static Dielectric Breakdown Strength of Condensed Heterogeneous High Explosives," NSWC TR 85-380 (1987).

Ya. B. Zel’dovich and Yu. P. Raizer, Physics of Shock Waves and High-Temperature Hydrodynamic Phenomena (Nauka, Moscow, 1966; Dover, New York, 2002), Vols. 1 and 2.

W. Benenson, J. W. Harris, H. Stoker, and H. Lutz, Handbook of Physics (Springer, New York, 2002).

L. Pauling, General Chemistry (Dover, New York, 1988).

B. M. Dobratz and P. C. Crawford, LLNL Explosives Handbook: Properties of Chemical Explosives and Explosive Simulants(1985).

J. H. J. Niederhaus, R. E. Jorgenson, L. K. Warne, and K. C. Chen, “Radiation-MHD Simulators for the Development of a Spark Discharge Channel," SAND2017-4461 (2017).

M. Wright, “Development of the Floret Test for Screening the Initiability of Explosive Materials," AIP Conf. Proc.1426, 693 (2012); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.3686373.

P. W. Cooper, Explosives Engineering (Wiley-VCH, New York, 1996).

P. Urtiew and C. M. Tarver, “Shock Initiation of Energetic Materials at Different Initial Temperatures (Review)," Fiz. Goreniya Vzryva 41 (6), 181–192 (2005) [Combust., Expl., Shock Waves 41 (6), 766–776 (2005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, K.C., Warne, L.K., Jorgenson, R.E. et al. Direct Lightning Initiation of HMX. Combust Explos Shock Waves 56, 697–704 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1134/S001050822006009X

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1134/S001050822006009X