-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

J Wienert, K Spanier, F M Radoschewski, M Bethge, Work ability, effort–reward imbalance and disability pension claims, Occupational Medicine, Volume 67, Issue 9, December 2017, Pages 696–702, https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqx164

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Effort–reward imbalance (ERI) and self-rated work ability are known independent correlates and predictors of intended disability pension claims. However, little research has focused on the interrelationship between the three and whether self-rated work ability mediates the relationship between ERI and intended disability pension claims.

To investigate whether self-rated work ability mediates the association between ERI and intended disability pension claims.

Baseline data from participants of the Third German Sociomedical Panel of Employees, a 5-year cohort study that investigates determinants of work ability, rehabilitation utilization and disability pensions in employees who have previously received sickness benefits, were analysed. We tested direct associations between ERI with intended disability pension claims (Model 1) and self-rated work ability (Model 2). Additionally, we tested whether work ability mediates the association between ERI and intended disability pension claims (Model 3).

There were 2585 participants. Model 1 indicated a significant association between ERI and intended disability pension claims. Model 2 showed a significant association between ERI and self-rated work ability. The mediation in Model 3 revealed a significant indirect association between ERI and intended disability pension claims via self-rated work ability. There was no significant direct association between ERI and intended disability pension claims.

Our results support the adverse health-related impact of ERI on self-rated work ability and intended disability pension claims.

Introduction

The rapid growth of transnational interdependence of capital, trade and labour that characterizes economic globalization transforms work and employment to achieve a higher level of competitiveness. These changes may be accompanied by work intensification, job insecurity, poor quality of work and wage inequalities [1–3].

One common model that links job conditions with occupational health is the effort–reward imbalance (ERI) model. The ERI model assumes that beneficial effects of employment, such as participation, self-efficacy and approval, depend on the fairness of the relationship between employer and employee and that employees expect adequate reward for their efforts, such as income, esteem, career opportunities and job security [4]. The model concludes that an imbalance between effort and reward results in psychological distress and adverse health effects. There is good evidence that links ERI to negative health outcomes such as coronary heart diseases and mental health problems. Not surprisingly, ERI is also linked to intention to retire and exit from paid employment [5,6].

One concept that may assist in understanding the pathway from ERI to retirement intentions is self-rated work ability. Ilmarinen [7] describes self-rated work ability as the interaction between individual determinants (e.g. health, competence and attitudes) and the work environment. A review by van den Berg et al. [8] identified various factors that restrict self-rated work ability, such as lack of physical activity, poor musculoskeletal capacity, obesity, high mental work demands, lack of autonomy, poor physical work environment and high physical work demands. Further cross-sectional and longitudinal studies also report an independent link between ERI and poor self-rated work ability [9–11].

Numerous studies showed that poor self-rated work ability is linked to intention to retire from the labour market and early retirement. Evidence suggests that among other factors, such as poor health, sickness absence, low job control and organizational injustice, poor self-rated work ability not only predicts retirement intentions by an odds ratio of 2.2 [12], but also increased productivity loss, long-term sickness absence, unemployment and early retirement [13–15]. This theoretical interdependence raises the question of whether self-rated work ability mediates the relationship between ERI and retirement intentions.

The aim of this study was to examine the associations between ERI, self-rated work ability and intended disability pension claims (i.e. early payment of pension due to permanent ill health affecting the workers’ ability to work in the long run) in a sample of employees with an elevated risk of restrictions in their labour market participation. Replicating past findings on the interrelationship between ERI, self-rated work ability and intended disability pension claims may provide more information to explore self-rated work ability as a potential mediator of the association between ERI and intended disability pension claims.

Methods

We used baseline data from a cohort with an increased risk of restrictions in their labour market participation. The gross sample of the Third German Sociomedical Panel of Employees comprised 10000 persons who were insured by the Federal German Pension Insurance (GPI) and who received sickness benefits in 2012, were aged 40–54 years and were currently living in Germany. The Federal GPI is part of the compulsory German insurance scheme and currently administers the pension contributions of about 23 million people. By law, the GPI can approve rehabilitation programmes for employees in order to improve and restore their ability to work, thereby avoiding ill-health retirement. Samples of 5000 people were independently selected for women and men. People who had requested or had been granted pension benefits as well as people who had already received or applied for benefits between 2009 and 2012 were excluded. The study protocol received approval from the ethics committee of the Hannover Medical School (No. 1730-2013) and from the data protection commissioner of the Federal GPI. The study is registered in the German Clinical Trials Register (DRKS00004824). People selected for the sample were contacted in May 2013 by post and provided with study information, a questionnaire and a franked envelope to return the questionnaire. A reminder was sent after 6 weeks.

Intended disability pension claim was assessed with a single binary item asking: ‘Are you currently thinking about applying for a pension due to health problems?’ Participants indicated yes or no.

Self-rated work ability was assessed using the Work Ability Score (WAS). The WAS is the first item of the Work Ability Index (WAI) and assesses current work ability compared with the self-reported lifetime best [7]. This is an 11-point scale, where 0 represents complete incapacity to work and 10 represents lifetime best work ability. The WAS correlates highly with the overall WAI score [16].

ERI at work was assessed with the short version of the Effort–Reward Imbalance Questionnaire (ERIQ) developed by Siegrist et al. [1,17]. Effort was measured using three questions stating: (i) ‘I have constant time pressure due to a heavy work load’; (ii) ‘I have many interruptions and disturbances while performing my job’ and (iii) ‘Over the past few years, my job has become more and more demanding’. The reward scale comprised seven questions representing esteem, job security and promotion/salary. Esteem was assessed with two questions: (i) ‘I receive the respect I deserve from my superior or a respective relevant person’ and (ii) ‘Considering all my efforts and achievements, I receive the respect and prestige I deserve at work’. Job security was assessed with two questions: (i) ‘I have experienced or I expect to experience an undesirable change in my work situation’ and (ii) ‘My job security is poor’. Promotion/salary was assessed with three questions: (i) ‘My job promotion prospects are poor’; (ii) ‘Considering all my efforts and achievements, my job promotion prospects are adequate’ and (iii) ‘Considering all my efforts and achievements, my salary/income is adequate’. All domains were assessed using four-point Likert scales ranging from ‘totally disagree’ to ‘totally agree’. ERI was calculated as the ratio of the sum of scores on the effort and reward scales (ER ratio). The reward score was multiplied by a correction factor to account for the different number of items in the numerator and denominator. An ER ratio >1 indicates that efforts are higher than rewards.

Health-related risk factors were assessed using the body mass index (BMI), sports activity and smoking. Participants were asked to indicate their height and weight. A BMI ≥30 kg/m2 was considered to be obese. Sports activity was assessed by a single question asking whether a person had followed a regular sport, fitness or gymnastic routine throughout the past 12 months using a five-point ordinal scale ranging from ‘4 and more hours every week’ to ‘never’. Sports activity was categorized as <2 h per week versus ≥2 h a week. Smoking was assessed by a single item asking whether a person currently smokes (smoker versus non-smoker).

Social support was assessed using the Oslo 3-Item Social Support Scale [18]. The items measure the number of close friends you can count on when facing severe problems, how much concern people show in what you are doing and how easily you can get help in the neighbourhood if needed. All answers are summed up to a score ranging from 3 to 14 points. The score was categorized into low social support (3–8 points), moderate social support (9–11 points) and high social support (12–14 points) [18].

Physical workload was assessed with five questions using a four-point scale ranging from never (zero point) to often (three points) asking: ‘In the following, please indicate how often the following points describe the physical workload of your current job’: (i) ‘Heavy physical work’; (ii) ‘Holding heavy loads’; (iii) ‘Carrying heavy loads’; (iv) ‘Lifting heavy loads’ and (v) ‘Pulling/pushing heavy loads’. All answers were summed up to a total score ranging from 0 to 15 points [19]. The upper quartile of this score was classified as high physical workload.

Age (in 5-year groups), sex (female versus male), high educational level (high school diploma versus lower grades) and partnership (no partnership versus partnership) were considered relevant socio-demographic parameters.

We tested direct associations between ERI and the odds of intention to claim disability pension using logistic regression (Model 1) and self-rated work ability using linear regression (Model 2). The estimations of the associations were adjusted for age, sex, educational level, partnership, BMI, physical activity, smoking, social support and physical job demands. Additionally, we tested whether self-rated work ability mediated the association between ERI and intended disability pension claims using path analysis (Model 3). Unstandardized coefficients are reported for variables in the linear regression model and odds ratios for the logistic regression model.

Following Baron and Kenny’s [20] principles for mediation analysis, we define c as the total effect of ERI on intended disability pension claims. The immediate relationship between ERI and intended disability pension claims represents the direct effect c in our Model 3. Path a characterized the effect of ERI regressed on self-rated work ability and path b the effect of self-rated work ability regressed on intended disability pension claims. The indirect effect is represented by multiplying the a- and b-path. The total effect c is the sum of the direct and indirect effect, i.e. c = a * b + c′. A reduction of the direct effect c, compared to c, indicates a mediation effect of self-rated work ability. Additionally, the proportion of the indirect effect is reported by (a * b)/(a * b + c′). To determine the quality of each model, R2 and Nagelkerke R2 (N-R2) are reported. Requirements for linear regression were tested and fulfilled. P values were considered significant if they were <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 22.0 and Mplus 7.3 for Windows.

Results

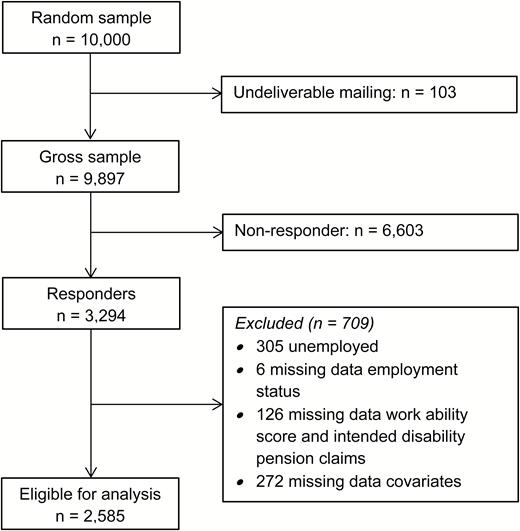

From the 10000 questionnaires that were sent out, 103 were undeliverable and 3294 of the questionnaires returned met the study criteria (response rate 33%) (Figure 1).

A total of 2585 participants were included for analysis. Participants who were not working were excluded from the analyses (n = 305), as well as participants who provided no information about whether they were working or not (n = 6). Additionally, participants who provided no information about self-rated work ability or intended disability pension claims (n = 126) or had missing data on covariates (n = 272) were excluded. The mean age was 47.8 years (SD = 4.1) and 53% were female. About one-fifth reported a high educational level (21%). The mean ERI was 1.3 (SD = 0.6) and the mean WAS was 6.8 (SD = 2.4). Overall, 6% indicated that they were considering applying for ill-health retirement. The sample characteristics are reported in Table 1. Additional box plots depicting upper and lower quartiles for self-rated work ability and ER ratio in relation to intended dis- ability pension claims and self-rated work ability versus effort reward ratio can be found in Figure S1 (available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online).

Descriptive data on study participants for the complete sample, with intended disability pension claims and with no intended disability pension claims

| . | Complete sample (n = 2585) . | Intended disability pension claims (n = 148) . | No intended disability pension claims (n = 2437) . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | |

| Age in years | 47.8 | 4.1 | 49.1 | 4.0 | 47.8 | 4.1 | ||||

| Female | 1367 (53) | 65 (44) | 1302 (53) | |||||||

| High educational level | 552 (21) | 16 (11) | 536 (22) | |||||||

| No partner | 554 (21) | 36 (24) | 518 (21) | |||||||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 579 (22) | 46 (31) | 533 (22) | |||||||

| Sports activity < 2 h/week | 1602 (62) | 114 (77) | 1488 (61) | |||||||

| Smoker | 724 (28) | 46 (31) | 678 (28) | |||||||

| Social support | 9.6 | 2.3 | 8.9 | 2.4 | 9.7 | 2.2 | ||||

| Low | 806 (31) | 67 (45) | 739 (30) | |||||||

| Moderate | 1224 (47) | 58 (39) | 1166 (48) | |||||||

| Physical workload | 4.9 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 4.9 | ||||

| High | 569 (22) | 45 (30) | 524 (22) | |||||||

| Effort–reward ratio | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.6 | ||||

| WAS | 6.8 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 6.9 | 2.3 | ||||

| . | Complete sample (n = 2585) . | Intended disability pension claims (n = 148) . | No intended disability pension claims (n = 2437) . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | |

| Age in years | 47.8 | 4.1 | 49.1 | 4.0 | 47.8 | 4.1 | ||||

| Female | 1367 (53) | 65 (44) | 1302 (53) | |||||||

| High educational level | 552 (21) | 16 (11) | 536 (22) | |||||||

| No partner | 554 (21) | 36 (24) | 518 (21) | |||||||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 579 (22) | 46 (31) | 533 (22) | |||||||

| Sports activity < 2 h/week | 1602 (62) | 114 (77) | 1488 (61) | |||||||

| Smoker | 724 (28) | 46 (31) | 678 (28) | |||||||

| Social support | 9.6 | 2.3 | 8.9 | 2.4 | 9.7 | 2.2 | ||||

| Low | 806 (31) | 67 (45) | 739 (30) | |||||||

| Moderate | 1224 (47) | 58 (39) | 1166 (48) | |||||||

| Physical workload | 4.9 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 4.9 | ||||

| High | 569 (22) | 45 (30) | 524 (22) | |||||||

| Effort–reward ratio | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.6 | ||||

| WAS | 6.8 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 6.9 | 2.3 | ||||

Descriptive data on study participants for the complete sample, with intended disability pension claims and with no intended disability pension claims

| . | Complete sample (n = 2585) . | Intended disability pension claims (n = 148) . | No intended disability pension claims (n = 2437) . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | |

| Age in years | 47.8 | 4.1 | 49.1 | 4.0 | 47.8 | 4.1 | ||||

| Female | 1367 (53) | 65 (44) | 1302 (53) | |||||||

| High educational level | 552 (21) | 16 (11) | 536 (22) | |||||||

| No partner | 554 (21) | 36 (24) | 518 (21) | |||||||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 579 (22) | 46 (31) | 533 (22) | |||||||

| Sports activity < 2 h/week | 1602 (62) | 114 (77) | 1488 (61) | |||||||

| Smoker | 724 (28) | 46 (31) | 678 (28) | |||||||

| Social support | 9.6 | 2.3 | 8.9 | 2.4 | 9.7 | 2.2 | ||||

| Low | 806 (31) | 67 (45) | 739 (30) | |||||||

| Moderate | 1224 (47) | 58 (39) | 1166 (48) | |||||||

| Physical workload | 4.9 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 4.9 | ||||

| High | 569 (22) | 45 (30) | 524 (22) | |||||||

| Effort–reward ratio | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.6 | ||||

| WAS | 6.8 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 6.9 | 2.3 | ||||

| . | Complete sample (n = 2585) . | Intended disability pension claims (n = 148) . | No intended disability pension claims (n = 2437) . | . | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | n (%) . | Mean . | SD . | |

| Age in years | 47.8 | 4.1 | 49.1 | 4.0 | 47.8 | 4.1 | ||||

| Female | 1367 (53) | 65 (44) | 1302 (53) | |||||||

| High educational level | 552 (21) | 16 (11) | 536 (22) | |||||||

| No partner | 554 (21) | 36 (24) | 518 (21) | |||||||

| BMI ≥ 30 | 579 (22) | 46 (31) | 533 (22) | |||||||

| Sports activity < 2 h/week | 1602 (62) | 114 (77) | 1488 (61) | |||||||

| Smoker | 724 (28) | 46 (31) | 678 (28) | |||||||

| Social support | 9.6 | 2.3 | 8.9 | 2.4 | 9.7 | 2.2 | ||||

| Low | 806 (31) | 67 (45) | 739 (30) | |||||||

| Moderate | 1224 (47) | 58 (39) | 1166 (48) | |||||||

| Physical workload | 4.9 | 4.9 | 6.1 | 5.4 | 4.8 | 4.9 | ||||

| High | 569 (22) | 45 (30) | 524 (22) | |||||||

| Effort–reward ratio | 1.3 | 0.6 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 1.3 | 0.6 | ||||

| WAS | 6.8 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 2.7 | 6.9 | 2.3 | ||||

The first regression model indicated a significant correlation between ERI and intended disability pension claims. A one-point increase in ERI raised the odds of intending to claim a disability pension by 50%. Besides ERI, age and low sports activity were positively associated with intended disability pension claims. Additionally, women and people with a higher educational level had lower odds of intending to make an application (Table 2). The second regression model indicated a significant association between ERI and self-rated work ability. With an increase of one point in ERI, the WAS decreased by approximately one point, which represents about half a standard deviation. Besides ERI, age, low sports activity, low social support and high physical workload were negatively associated with self-rated work ability (Table 2).

Determinants of intended disability pension claims by logistic regression self-rated work ability by linear regression

| . | Intended disability pension claims . | Self-rated work ability . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | OR . | 95% CI . | b . | 95% CI . |

| Effort–reward ratio | 1.49** | 1.13 to 1.96 | −0.94*** | −1.10 to −0.79 |

| Age (5-year steps) | 1.54*** | 1.23 to 1.91 | −0.19** | −0.29 to −0.08 |

| Female | 0.69* | 0.49 to 0.97 | −0.05 | −0.22 to 0.13 |

| High educational level | 0.49** | 0.28 to 0.83 | −0.02 | −0.20 to 0.23 |

| No partnership | 1.14 | 0.77 to 1.71 | −0.06 | −0.15 to 0.27 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 1.27 | 0.88 to 1.85 | −0.20 | −0.41 to 0.01 |

| Sports activity < 2 h/week | 1.82** | 1.22 to 2.73 | −0.52*** | −0.70 to −0.34 |

| Smoker | 1.00 | 0.69 to 1.45 | −0.02 | −0.22 to −0.17 |

| Low social support | 1.53 | 0.92 to 2.54 | −0.93*** | −1.18 to −0.68 |

| Moderate social support | 0.98 | 0.59 to 1.61 | −0.31** | −0.54 to −0.08 |

| High physical workload | 1.36 | 0.93 to 2.00 | −0.28* | −0.49 to −0.06 |

| N-R2 = 0.06 | R2 = 0.12 | |||

| . | Intended disability pension claims . | Self-rated work ability . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | OR . | 95% CI . | b . | 95% CI . |

| Effort–reward ratio | 1.49** | 1.13 to 1.96 | −0.94*** | −1.10 to −0.79 |

| Age (5-year steps) | 1.54*** | 1.23 to 1.91 | −0.19** | −0.29 to −0.08 |

| Female | 0.69* | 0.49 to 0.97 | −0.05 | −0.22 to 0.13 |

| High educational level | 0.49** | 0.28 to 0.83 | −0.02 | −0.20 to 0.23 |

| No partnership | 1.14 | 0.77 to 1.71 | −0.06 | −0.15 to 0.27 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 1.27 | 0.88 to 1.85 | −0.20 | −0.41 to 0.01 |

| Sports activity < 2 h/week | 1.82** | 1.22 to 2.73 | −0.52*** | −0.70 to −0.34 |

| Smoker | 1.00 | 0.69 to 1.45 | −0.02 | −0.22 to −0.17 |

| Low social support | 1.53 | 0.92 to 2.54 | −0.93*** | −1.18 to −0.68 |

| Moderate social support | 0.98 | 0.59 to 1.61 | −0.31** | −0.54 to −0.08 |

| High physical workload | 1.36 | 0.93 to 2.00 | −0.28* | −0.49 to −0.06 |

| N-R2 = 0.06 | R2 = 0.12 | |||

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; N-R2 = Nagelkerke R2.

Determinants of intended disability pension claims by logistic regression self-rated work ability by linear regression

| . | Intended disability pension claims . | Self-rated work ability . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | OR . | 95% CI . | b . | 95% CI . |

| Effort–reward ratio | 1.49** | 1.13 to 1.96 | −0.94*** | −1.10 to −0.79 |

| Age (5-year steps) | 1.54*** | 1.23 to 1.91 | −0.19** | −0.29 to −0.08 |

| Female | 0.69* | 0.49 to 0.97 | −0.05 | −0.22 to 0.13 |

| High educational level | 0.49** | 0.28 to 0.83 | −0.02 | −0.20 to 0.23 |

| No partnership | 1.14 | 0.77 to 1.71 | −0.06 | −0.15 to 0.27 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 1.27 | 0.88 to 1.85 | −0.20 | −0.41 to 0.01 |

| Sports activity < 2 h/week | 1.82** | 1.22 to 2.73 | −0.52*** | −0.70 to −0.34 |

| Smoker | 1.00 | 0.69 to 1.45 | −0.02 | −0.22 to −0.17 |

| Low social support | 1.53 | 0.92 to 2.54 | −0.93*** | −1.18 to −0.68 |

| Moderate social support | 0.98 | 0.59 to 1.61 | −0.31** | −0.54 to −0.08 |

| High physical workload | 1.36 | 0.93 to 2.00 | −0.28* | −0.49 to −0.06 |

| N-R2 = 0.06 | R2 = 0.12 | |||

| . | Intended disability pension claims . | Self-rated work ability . | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| . | OR . | 95% CI . | b . | 95% CI . |

| Effort–reward ratio | 1.49** | 1.13 to 1.96 | −0.94*** | −1.10 to −0.79 |

| Age (5-year steps) | 1.54*** | 1.23 to 1.91 | −0.19** | −0.29 to −0.08 |

| Female | 0.69* | 0.49 to 0.97 | −0.05 | −0.22 to 0.13 |

| High educational level | 0.49** | 0.28 to 0.83 | −0.02 | −0.20 to 0.23 |

| No partnership | 1.14 | 0.77 to 1.71 | −0.06 | −0.15 to 0.27 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 1.27 | 0.88 to 1.85 | −0.20 | −0.41 to 0.01 |

| Sports activity < 2 h/week | 1.82** | 1.22 to 2.73 | −0.52*** | −0.70 to −0.34 |

| Smoker | 1.00 | 0.69 to 1.45 | −0.02 | −0.22 to −0.17 |

| Low social support | 1.53 | 0.92 to 2.54 | −0.93*** | −1.18 to −0.68 |

| Moderate social support | 0.98 | 0.59 to 1.61 | −0.31** | −0.54 to −0.08 |

| High physical workload | 1.36 | 0.93 to 2.00 | −0.28* | −0.49 to −0.06 |

| N-R2 = 0.06 | R2 = 0.12 | |||

*P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; N-R2 = Nagelkerke R2.

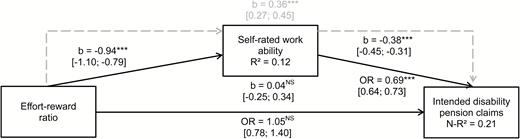

For the mediation model, predictors from the first and second regression model were included for analysis to provide a comprehensive path model estimating direct and indirect effects (Figure 2). ERI was significantly associated with self-rated work ability, and self-rated work ability was significantly associated with intended disability pension claims. The mediation model identified a significant indirect effect of ERI on intended disability pension claims via self-rated work ability. No significant association between ERI and intended disability pension claims was found. Self-rated work ability mediated 89% of the association between ERI and intended disability pension claims. A table with the complete estimated model, including all unstandardized and bias-corrected bootstrap coefficients with 5000 draws, can be found in Table S1 (available as Supplementary data at Occupational Medicine Online).

Mediation model for ERI, self-rated work ability and intended disability pension claims controlled for significant predictors from Tables 1 and 2 with direct (solid lines) and indirect (dotted lines) effects and 95% confidence intervals. When applicable, unstandardized coefficients and odds ratios are jointly reported. ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

Our results confirmed associations between ERI with self-rated work ability and intended disability pension claims and show that the association with intended disability pension claims is mediated via work ability. Our study illustrates the association between ERI and retirement intentions and shows that self-rated work ability is an important outcome for planning interventions to promote employment and to reduce early retirement. The effect of ERI on retirement intentions is not simply a desire to avoid adverse work conditions but seems to be associated with self-rated work ability. There are, on the one hand, several systematic reviews that confirm the adverse health effects of ERI [21, 22]. On the other hand, ERI means that the employer may undervalue or question a worker’s attitudes and competencies. From this perspective, the effect of ERI on self-rated work ability may be an internalization of the interaction between employer and employee by incorporating the external perception of the employer. Unfairness and disrespect may then negatively impact on attitudes and competencies, while fair treatment and respect may positively impact on attitudes and competencies.

Besides ERI, our first model identified older age, low levels of sport activity, low to moderate social support and high physical workload as negative predictors of self-rated work ability, thereby partly supporting the results found by van den Berg et al. [8]. Older age and lower levels of sports activity may represent proxies for poor health status, which, in turn, may be related to lower self-rated work ability. Adequate levels of sport or physical activity are clearly linked to health benefits. Additionally, jobs with a high physical workload may lead to musculoskeletal disorders (e.g. low back pain), which adversely affect health [23] and thereby may decrease self-rated work ability. While some studies show that social support does not significantly predict lower self-rated work ability [9], others show that social support can increase it and facilitate return to work [24].

Our second model showed that, alongside ERI, older age and low levels of sport activity increased the odds of intended disability pension claims, while being female and having a higher educational level lowered the odds of intended disability pension claims. This is supported by a review showing that increasing age as well as a lack of activity are associated with retirement [25] and may also be in line with the results found by van den Berg et al. [6], as older age and low levels of activity may represent proxies for poor health status. However, the same review also concludes that the results on gender and education are inconclusive [6]. While our study found that being female lowered the odds of intended disability pension claims some studies report that gender has no effect on actual retirement age [26] or intention to retire [27], while others agree with our findings [28]. Some researchers argue that there are gender differences in experience of the retirement process with regard to differing work histories, employment opportunities, general life experience and negative attitudes towards retirement as well as satisfaction with retirement [3,29,30]. Our results on higher education lowering the odds of intended disability pension claims are in line with previous studies. Odds ratios of 2.5 and 2.1–3.1 were reported by Solem et al. [28] Taylor et al. [27], respectively.

Despite meeting the stated research aims, the following limitations need to be mentioned. Only cross-sectional data were analysed, making it impossible to draw any conclusions on the proposed mediation effect on intended disability pension claims in the long term. Furthermore, as suggested by Kim and Moen [3], underlying attitudes towards early retirement may provide additional explanatory value to intended disability pension claims. These, however, were not assessed by the current study. Additionally, our study focussed on a very specific population with an increased risk of restrictions in labour market participation, as received sickness benefits are a good indicator of early retirement from the labour market. This could indicate that reported self-rated work ability probably does not reflect the broad population, limiting the generalizability of our results. Another limitation concerns the small amount of explained variance in intended disability pension claims and self-reported work ability, indicating that there may be other variables not included in the current analyses which may help to explain intended disability pension claims and self-reported work ability.

Despite these limitations, our results fit well with the current body of evidence and contribute to the understanding of potential associations between work-related stress, self-rated work ability and intended disability pension claims. Additionally, our sample represents a population at risk of early disability pension claims, providing useful evidence of practical significance to employers, pension insurance agencies and other decision makers.

This study found significant associations between effort–reward imbalance and intended disability pension claims and between effort–reward imbalance and self-rated work ability.

The predicted model showed that work ability mediated the relationship between effort–reward imbalance and intended disability pension claims.

The study demonstrated the importance of considering indirect pathways when examining the impact of effort–reward imbalance on intentions to retire early from the labour market due to sickness.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.