-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Gill Rumsby, Abhishek Sharma, David P. Cregeen, Laurie R. Solomon, Primary hyperoxaluria type 2 without l‐glycericaciduria: is the disease under‐diagnosed?, Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Volume 16, Issue 8, August 2001, Pages 1697–1699, https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/16.8.1697

Close - Share Icon Share

Introduction

The primary hyperoxalurias (PH) are inherited disorders of endogenous oxalate overproduction. Type 1 (PH1) is caused by deficiency of hepatic peroxisomal alanine: glyoxylate aminotransferase (AGT) [1] and type 2 (PH2) by glyoxylate reductase (GR) deficiency [2]. The differential diagnosis formerly relied on the finding of hyperglycolic aciduria in PH1 and l‐glycericaciduria in PH2, but it is now known that approximately one third of PH1 patients have urine glycolate within the reference range [3] and that raised urinary glycolate may occur in patients without PH1 [4]. There is less information about PH2 and it has been believed that the absence of l‐glycericaciduria excluded the diagnosis of PH2.

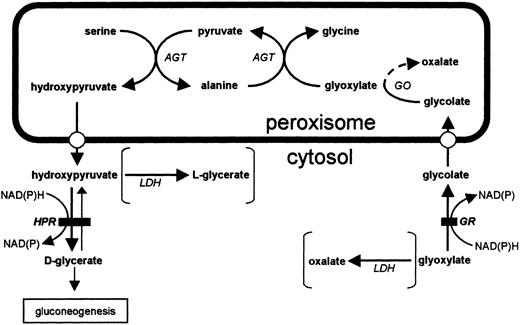

In PH2 glyoxylate and hydroxypyruvate are metabolized by lactate dehydrogenase to oxalate and l‐glycerate respectively [5] (Figure 1). This observation is consistent with deficiency of a single protein having both glyoxylate and hydroxypyruvate reductase (HPR) activity and this has now been demonstrated by identification and expression of the gene [6,7]. The major role of this enzyme may be the prevention of cytosolic glyoxylate accumulation. Loss of the enzyme therefore increases the amount of glyoxylate available for metabolism by lactate dehydrogenase to oxalate.

We describe a patient with hyperoxaluria, renal stones and renal failure who had PH2 diagnosed by measurement of GR and HPR activity in a liver biopsy and confirmed by lack of immuno‐reactive glyoxylate reductase protein but who did not have excess l‐glycerate in the urine.

Glyoxylate metabolism in the hepatocyte. Solid bar denotes site of block in PH2 and metabolites typically associated with the disease are given in parentheses. AGT, alanine: glyoxylate aminotransferase; GR, glyoxylate reductase; HPR, hydroxypyruvate reductase; GO, glycolate oxidase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase.

Case

The patient had formed renal stones since the age of four when an IVP showed renal calculi and he was admitted for their removal from the ureter. After this, he remained asymptomatic until aged 39 when in June 1988 he had a road traffic accident which caused spastic quadriparesis. In June 1990 he presented to his general practitioner with frank haematuria. Investigations showed plasma creatinine 280 μmol/l and a midstream urine grew Escherichia coli, which was treated with antibiotics. Ultrasound scan and IVP were normal but he passed a small stone 3 months later and analysis showed calcium oxalate. In January 1992 a 24 h urine contained 1.08 mmol oxalate. Between 1992 and 1995 he had several more episodes of renal colic and suspected urinary infection, four IVPs showed stones in both kidneys and he passed at least five more stones.

He was referred to the renal out‐patient department in July 1996 at the age of 47 for investigation of hypertension, renal impairment and proteinuria. Investigations included serum creatinine 273 μmol/l, urea 15.3 mmol/l, calcium 2.44 mmol/l, creatinine clearance 20 ml/min, urinary protein 0.49 g/24 h, urine calcium 0.8 mmol/24 h, urinary oxalate 1.58 and 1.48 mmol/24 h (0.08–0.49) in separate samples. Urinary organic acid analysis failed to demonstrate l‐glycerate (measured by gas chromatography) and provisionally excluded PH2. Glycolate excretion was 0.08 mmol/24 h (reference range 0.1–0.33). A renal biopsy in December 1996 showed 18 of 28 glomeruli were totally sclerosed but the remainder looked normal. There was focal tubular atrophy and mild chronic inflammation and occasional crystals in some of the tubules. He was commenced on pyridoxine 50 mg once daily and calcium carbonate 1.25 g twice daily.

He was lost to follow‐up in the renal clinic until October 1999 when he presented with loin pain and advanced renal failure (urea 23 mmol/l, creatinine 780 μmol/l) three months after having extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy for a left‐sided staghorn calculus. An ultrasound scan excluded obstruction. Suspicion remained that he had underlying metabolic cause for hyperoxaluria and he therefore had a liver biopsy in December 1999. Urine glycerate was reported detectable but not raised. He started haemodialysis in February 2000.

Liver enzyme analysis

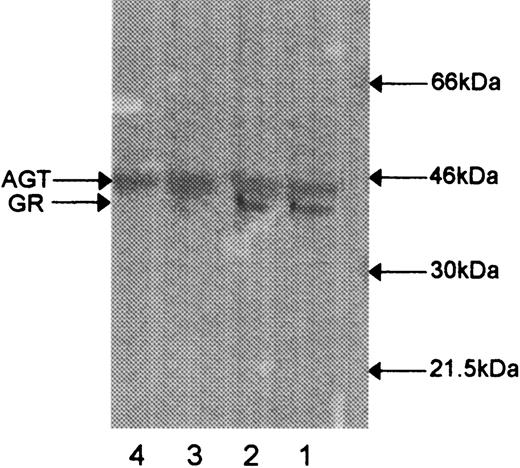

The liver biopsy was analysed for AGT, GR and HPR activities as previously described [8,9]. AGT activity was within normal limits but HPR and GR activities were both reduced at 133 nmol.min−1.mg protein−1 (reference range 322–1002) and 21 nmol.min−1.mg protein−1 (reference range 49–213) respectively. Absence of GR‐specific protein in the liver was demonstrated on Western blots using antibody raised to expressed human GR (Figure 2). Immunoreactive AGT was used as a control for sample application.

Western blot analysis of human liver sonicates hybridized with antibodies to AGT and GR. Lanes 1 and 2, control; lanes 3 and 4, patient.

Family study

One of the patient's two brothers reported stones, which had been removed surgically when he was a baby. He had further episodes of renal colic at the ages of 16 and 31, when an abdominal X‐ray suggested a stone at the lower end of the left ureter and he passed debris in the urine. He was reviewed at age 48, when he was found to have a raised urinary oxalate of 0.73 mmol/24 h (reference range 0.1–0.46 mmol/24 h). Urine glycerate was reported as present but not elevated. Plasma urea and creatinine were 4.7 mmol/l and 84 μmol/l respectively. Liver biopsy was not undertaken.

Discussion

This case demonstrates that PH2 may occur without l‐glycericaciduria and reliance on this finding may miss the diagnosis, which requires liver biopsy. The absence of l‐glyceric aciduria may have resulted from partial enzyme impairment. GR activity was not zero as in most of the liver biopsies analysed from patients with this disease [9] [Rumsby, unpublished data] although there was significant reduction of immunoreactive GR protein compared to control liver biopsies. The residual enzyme activity may be sufficient to metabolize hydroxypyruvate normally while inadequate for the reduction of glyoxylate, the enzyme having a higher affinity for hydroxypyruvate than for glyoxylate [10].

Both brothers gave a history of stones in infancy and probably have the same metabolic defect. The propositus developed frequent stones and renal failure after a road accident caused quadriparesis. Immobilization hypercalciuria may have been a second contributory factor. It is possible that his brother has a more typical phenotype and that similar partial enzyme defects will be found in other patients with moderate hyperoxaluria and occasional stone formation.

It is already known that PH2 may be underdiagnosed either by misclassification as PH1 or through the lack of available urinary l‐glycerate assays. For example Milliner and colleagues [11] found that more thorough examination of 30 patients with PH1 identified five who had PH2. It is also particularly difficult to diagnose metabolic hyperoxaluria in cases presenting in end‐stage renal failure and a true diagnosis may be missed [12]. Our patient illustrates that PH2 may also be excluded despite the standard investigation because some patients do not have significant l‐glycericaciduria. Liver biopsy, although invasive, is currently the most reliable method of confirming the diagnosis of both types of PH [8,13] and should be undertaken more often following thorough biochemical investigation.

Correspondence and offprint requests to: G. Rumsby, Department of Chemical Pathology, UCL Hospitals, Windeyer Building, Cleveland street, London W1P 6DB, UK.

The developmental aspects of this work were funded by a grant to GR from the Sir Jules Thorn Charitable Trust.

References

Danpure CJ, Jennings PR, Watts RW. Enzymological diagnosis of primary hyperoxaluria type 1 by measurement of hepatic alanine: glyoxylate aminotransferase activity.

Mistry J, Danpure CJ, Chalmers RA. Hepatic d‐glycerate dehydrogenase and glyoxylate reductase deficiency in primary hyperoxaluria type 2.

Danpure CJ. Molecular and clinical heterogeneity in primary hyperoxaluria type 1.

Van Acker KJ, Eyskens FJ, Espeel MF, Wanders RJA, Dekker C, Kerckaert IO, Roels F. Hyperoxaluria with hyperglycoluria not due to alanine: glyoxylate aminotransferase defect: A novel type of primary hyperoxaluria.

Williams H, Smith LJ. l‐glyceric aciduria. A new genetic variant of primary hyperoxaluria.

Rumsby G, Cregeen D. Identification and expression of a cDNA for human hydroxypyruvate/glyoxylate reductase.

Cramer SD, Ferree PM, Lin K, Milliner DS, Holmes RP. The gene encoding hydroxypyruvate reductase (GRHPR) is mutated in patients with primary hyperoxaluria type II.

Rumsby G, Weir T, Samuell CT. A semiautomated alanine : glyoxylate aminotransferase assay for the tissue diagnosis of primary hyperoxaluria type 1.

Giafi CF, Rumsby G. Kinetic analysis and tissue distribution of human d‐glycerate dehydrogenase/glyoxylate reductase and its relevance to the diagnosis of primary hyperoxaluria type 2.

Cregeen DP, Rumsby G. Recent developments in our understanding of primary hyperoxaluria type 2.

Chlebeck PT, Milliner DS, Smith LH. Long‐term prognosis in primary hyperoxaluria type II (l‐glyceric aciduria).

Marangella M, Petrarulo M, Cosseddu D, Vitale C, Cadario A, Portigliatti Barbos M, Gurioli L, Linari F. Detection of primary hyperoxaluria type 2 (l‐glyceric aciduria) in patients with end stage renal failure.

Comments