-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

David R. Buys, Casey Borch, Patricia Drentea, Mark E. LaGory, Patricia Sawyer, Richard M. Allman, Richard Kennedy, Julie L. Locher, Physical Impairment Is Associated With Nursing Home Admission for Older Adults in Disadvantaged But Not Other Neighborhoods: Results From the UAB Study of Aging, The Gerontologist, Volume 53, Issue 4, August 2013, Pages 641–653, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gns118

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Objectives: Aging adults face an increased risk of adverse health events as well as risk for a decrease in personal competencies across multiple domains. These factors may inhibit the ability of an older adult to age in place and may result in a nursing home admission (NHA). This study combines insights from Lawton’s environmental press theory with the neighborhood disadvantage (ND) literature to examine the interaction of the neighborhood environment and individual characteristics on NHA. Methods: Characteristics associated with the likelihood of NHA for community-dwelling older adults were examined using data collected for 8.5 years from the UAB Study of Aging. Logistic regression models were used to test direct effects of ND on NHA for all participants. The sample was then stratified into 3 tiers of ND to examine differences in individual-level factors by level of ND. Results: There was no direct link between living in a disadvantaged neighborhood environment and likelihood of NHA, but physical impairment was associated with NHA for older adults living highly disadvantaged neighborhood environments in contrast to older adults living in less disadvantaged neighborhood environments, where no association was observed. Discussion: These outcomes highlight (a) the usefulness of linking Lawton’s theories of the environment with the ND literature to assess health-related outcomes and (b) the importance of neighborhood environment for older adults’ ability to age in place.

Where an older adult spends the last years of their life, in the community or in nursing facilities, is becoming more important as the average age of persons in the United States continues to rise and costs associated with caring for the aging population increases (Pynoos, Nishita, Cicero, & Caraviello, 2008). For older adults there is often a tension between the desire to “age in place” and the need for formal nursing home care because of functional or cognitive impairments and a lack of support to compensate for those declines (Chen & Wilmoth, 2004).

“Aging in place” refers to older adults’ continuing to live in their homes and communities regardless of illnesses or other disabilities (Pynoos & Nishita, 2007). In contrast, nursing homes are facilities where staff and equipment provide assistance with activities of daily living, skilled nursing care, skilled rehabilitation services and/or other related health services (Medicare, 2010). It is important to more fully understand the reasons why older adults are admitted to nursing homes to target interventions that may prevent or delay institutionalization. This paper explicates the nature of the association between neighborhood disadvantage (ND) and nursing home admission (NHA) by linking two previously independent theoretical perspectives. The resulting framework is tested using data from the UAB Study of Aging.

Predictors of NHA

Many factors have been identified as contributing to NHA. Most research has focused on either individual-level characteristics (e.g., income, gender, race and functional, and cognitive status) or social characteristics (e.g., marital status, living arrangement, social networks, and social support) (Gaugler, Duval, Anderson, & Kane, 2007; Luppa, Luck, Matschinger, Konig, & Riedel-Heller, 2010; Luppa, Luck, Weyerer, et al., 2010). Specifically, lower income has been associated with a higher risk of NHA (Gaugler et al., 2007). Evidence regarding the role of gender as a predictor of NHA among older adults is mixed (Harris, 2007; Harris & Cooper, 2006; Luppa, Luck, Weyerer, et al., 2010). Whites have been shown to be more than two times as likely to be placed in a nursing home as African Americans (Buhr, Kuchibhatla, & Clipp, 2006; Gaugler, Kane, Kane, Clay, & Newcomer, 2003; Scott, Edwards, Davis, Cornman, & Macera, 1997). Additionally, function and cognition represents individual-level capabilities needed to maintain independent living. Decline in each of those domains predicts NHA (Gaugler et al., 2007; Luppa, Luck, Matschinger, et al., 2010), because as functional and cognitive competencies decline, the need for support, from individuals and perhaps institutions, increases (Lawton, 1986).

Social support refers to the various forms of assistance available to individuals, which may include informational, emotional, or instrumental types of aid (Hooyman & Kiyak, 2007), all of which have been shown to be related to NHA. Living with a spouse decreases one’s likelihood of NHA (Gaugler et al., 2003), while persons living alone are generally more likely to experience NHA (Yaffe et al., 2002). A systematic review by Luppa, Luck, Weyerer, et al. (2010) demonstrated that a limited social network was associated with increased risk of NHA, suggesting that individuals are more likely to remain independent if they have reliable personal support available to compensate for functional and cognitive deficiencies. When these social networks are utilized, the older adult can mitigate the effects of their impairment that might otherwise lead to NHA.

Missing from the literature on factors associated with NHA is the role that one’s neighborhood environment may play (Gaugler et al., 2007), even though it has been acknowledged that an ecological approach to addressing issues of aging in place is warranted (Greenfield, 2012). Persons living in highly disadvantaged and disordered geographic spaces may be less able to navigate within or through their environment in order to access the resources necessary to maintain independence. A better understanding of the relationship between neighborhood environment and NHA is important as both a theoretical and practical endeavor. Recent work by Pruchno, Wilson-Genderson, and Cartwright (2012) demonstrated that neighborhoods have multiple dimensions and can influence the health of older adults in an array of ways. Notably, their work demonstrated that violence and broken storefronts in communities, characteristics of neighborhood disorder, are associated with rates of disability. It is important to know the nature of the relationship between neighborhood environment and health-related outcomes, particularly for older adults, to construct and implement interventions at the community level based on those neighborhood-level characteristics and needs. Additionally, this work may inform policy makers about where to direct health care services that may enable aging in place.

Theoretical Framework

A helpful framework for examining the role of neighborhood environment for older adults is found in the work of Powell Lawton, particularly his environmental press theory (Lawton, 1983; Lawton & Hoover, 1981; Lawton & Nahemow, 1973; Lawton & Simon, 1968; Lawton, Windley, & Byerts, 1982). More recent literature examining the effects of ND on individual health provides insight in considering the role of specific environments on health-related outcomes and ways to characterize the neighborhood for statistical modeling and evaluation. By linking these theoretical perspectives, we may be better able to understand how neighborhoods affect older adults.

Environmental Press.—

The environmental press theory helps to explain how older adults adjust to changes in their environment. The theory is expressed as:

where behavior (B) is a function of personal competencies (P); environment (E); and the interaction between them (P × E).

Personal and environmental factors are particularly relevant for older adults because of increased sensitivity to their surroundings (Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2000; Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2010; Lawton, 1983). Lawton’s theory holds that persons who are behaviorally less competent are more sensitive to environmental stressors. This notion of behavioral or personal competencies refers to individuals’ biological health, sensory and perceptual capacities, motor skills, and cognitive capacities. Environmental factors in this equation refer to both objective and subjective factors that put strain on an individual. These characteristics are found at three different levels including the physical, the personal, and the suprapersonal environments (Lawton, 1983). The physical environment refers to the non-personal and non-social elements of a person’s place, while the personal environment refers to significant interpersonal relationships such as family and close friends. The suprapersonal environment refers to the characteristics defining a person’s place in terms of the larger social environment such as the predominant race or mean age of a person’s neighborhood (Lawton et al., 1982). These environmental subcategories—the physical, personal, and suprapersonal—posited by Lawton together comprise the environment or the place in which life events unfold for individuals. Specifically, Lawton (1982) argues that some environments make high or “strong” behavioral demands on people while others do not. When behavioral outcomes are poor for an individual, it may be due to a misalignment of personal competencies and their environment (Lawton, 1983).

Neighborhood Disadvantage.—

The concept of neighborhood generally refers to the social, economic, cultural, and physical characteristics that comprise the area in which individuals reside (Moudon et al., 2006). According to Fitzpatrick and LaGory (2003), the neighborhood can be either a social resource, a source of risk for adverse outcomes, or some combination of both for individuals residing in them. Neighborhoods in which risks are high are characterized as disadvantaged neighborhoods. Resources and risks within the community can positively or negatively affect individuals’ health status (Kawachi & Berkman, 2003; Pruchno et al., 2012). Specifically, Mirowsky and Ross (2003) have shown that low socioeconomic status among people in a neighborhood is associated with higher levels of risk or hazard in that neighborhood, independent of their own disadvantage. Similarly, they have shown that positive conditions in a community may contribute to favorable health outcomes; as such, neighborhoods may encourage the practice of healthy lifestyles through positive social support and access to other resources (Ross & Mirowsky, 2001).

Common measures used to capture levels of ND include prevalence rates of poverty and single-mother households. These measures are representative of the nature of a community’s resources. Specifically, poverty rates represent economic disadvantage, and the prevalence of female-headed households represents social disadvantage (Ross, Mirowsky, & Pribesh, 2001). This is based on the notion that single mothers are often less able to devote as much time and energy parenting their own children and have limited time to contribute to their community, as compared with partnered mothers (Ross, 2000; Ross & Mirowsky, 2001; Ross et al., 2001). Due to this, single-mother households have been shown to be associated with higher levels of disorder (Wilson, 2011, 2012), which can increase psychosocial distress for persons living in those environments (Ross & Mirowsky, 2001).

Environmental Press and ND.—

Research on the impact of ND for health outcomes lends credence to Lawton’s work and may provide a useful way of conceptualizing individuals’ environments. This work uses the more recent ND literature, and the techniques, it presents for measuring neighborhood characteristics as a way of capturing the suprapersonal environment described by Lawton. To our knowledge, this is the first research to link these two bodies of literature and quantify the suprapersonal environment in such a manner.

Research Questions

The goal of this work is to answer two research questions: Are neighborhood environmental characteristics associated with the likelihood of NHA for older adults? Second, does the level of disadvantage in one’s neighborhood environment affect the level of association with other predictors of NHA?

Models

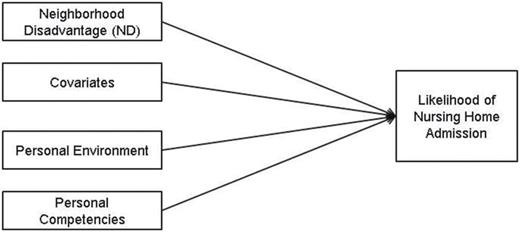

For this research, Lawton’s initial model was used to conceptualize the relationship between the environmental and personal factors and one’s likelihood of NHA over 8.5 years. The model was adapted into two forms. The first model (Figure 1) explores the direct relationship between the level of ND index (NDI) where one lives and the likelihood of NHA.

Analytic Model 1: assessing likelihood of nursing home admission.

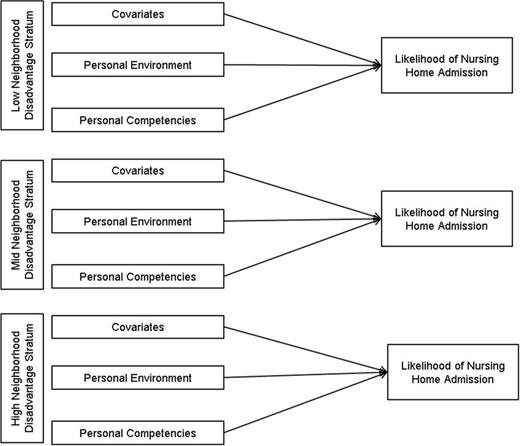

In Figure 2, the model was revised to test the effect of individual-level variables on likelihood of NHA within the different strata. For these analyses, the sample was stratified into three levels of ND, each of which was approximately the same size.

Analytic Model 2: stratified analysis of likelihood of nursing home admission.

These models capture the suprapersonal environment as measured by ND, the personal environment as measured by living alone and perceived social support, and personal competencies as measured by cognitive status, depression, and physical impairment. Figure 2 highlights the differences of individuals’ responses to various factors associated with NHA by the level of disadvantage in which they live. A stratified approach was used to examine the impact of ND on individual-level factors associated with NHA rather than hierarchical linear modeling (HLM), because HLM may lead to imprecise estimates due to an inadequate number of second-level variables, and persons nested within them, in this data set.

Methods

Sources of Data

Data from the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) Study of Aging (SOA) were used. The SOA is an observational, longitudinal study of 1,000 Medicare beneficiaries who, at baseline in 1999–2001, were community-dwelling persons aged 65 years and older living in five rural and urban counties in central Alabama. Participants represent a random sample of Medicare beneficiaries provided by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), stratified by race, gender, and residence. The population was oversampled for blacks, rural residents, and men. The final sample was 50% black, 51% rural, 50% women, and 51% married. Standardized questionnaires designed to assess mobility, social and demographic information, medical history, and health services utilization were collected at baseline in the home and in subsequent telephone follow-up interviews conducted every 6 months (Allman, Sawyer, & Roseman, 2006; Peel et al., 2005).

Additionally, participants’ addresses were geocoded, and the census tract characteristics were linked to data from the 2000 United States Census Summary Files 1 and 3. Characteristics found in these files at the census tract level were used to compute the neighborhood disadvantage index (NDI) as described by Ross, Mirowsky, and Pribesh (2001). Although using census tracts as a measure of neighborhood environment is limited by the fact that residents are not likely to recognize the seemingly invisible boundaries that are used for their demarcation (Pruchno et al., 2012), this level of measurement has been identified as an adequate and accepted tool for assessing neighborhood characteristics due to the limited availability of other data on neighborhoods (Aneshensel et al., 2007). The census tract has also been shown to detect socioeconomic gradients and neighborhood differences in the general population including populations of older adults (Krieger, Chen, Waterman, Rehkopf, & Subramanian, 2003). Before the project was initiated, the UAB institutional review board reviewed and approved both the UAB SOA and this project.

Analytic Sample

The final analytic sample was comprised of 993 participants. Three of the initial 1,000 participants were excluded because there was not adequate geographic information to identify their census tract, and four others were excluded due to missing data on key independent variables.

Dependent Variable: NHA

Likelihood of NHA is the dependent variable. Admission to a nursing home over the previous 6 months was ascertained at each interview. No persons enrolled in the study at baseline were in a nursing home, and the period of observation was 8.5 years from baseline. A participant was classified as being admitted to a nursing home at the first interview for which nursing home placement was reported, and this status was fixed.

Covariates

Poverty, an important variable used to distinguish the effects of individual disadvantage from ND, was conceptualized using the 2000 Federal Poverty Guidelines as a framework for setting cut points. Persons living alone with an income of $8,350 or persons living with someone with an income of less than $11,250 were considered poor according to that measure; therefore, we assigned poverty status to individuals living alone with an income of less than $8,000 and persons living with someone making less than $12,000 due to the categories available in the UAB Study of Aging. Additionally, age was reported in years at baseline and used as a continuous variable. Gender was included (1 = female), and race was reported as African American (coded 0) and White (coded 1).

Independent Variables

Environmental Variables.—

Environmental variables were conceptualized at the suprapersonal and personal levels.

Suprapersonal environment for individuals was measured at the characteristics census tract where they lived and conceptualized using the NDI (Ross et al., 2001). Persons in this study lived among 166 census tracts with 45 of the tracts having only one person represented in this study; 73 tracts had two, three, or four persons in the study living in the same tract, and 48 tracts had five or more persons in the tract. The NDI was generated from prevalence rates of poverty and female-headed households in the census tract and is reflective of neighborhood characteristics. In keeping with Ross, Mirowsky, and Pribesh (2001), the rates of poverty and female-headed households were divided by 10 and the mean of these values was assigned to individuals as the NDI. A one unit increase in the NDI represents a 10% increase in the prevalence of poverty and single-mother households at an individual’s census tract level. In this sample, the mean census tract rate of poverty is 17.2% with a minimum of 0.3% and a maximum of 58.6%.The mean rate of female-headed households is 9.7% with a range of 1.4–33.5%. For the second set of models, stratification of the participants by level of ND was completed by dividing the sample into three nearly equal groups, broken at the point nearest one-third of the sample with a different NDI value. Groups were labeled as low disadvantaged (n = 330), mid disadvantaged (n = 332), and high disadvantaged (n = 331).

Personal environment was measured by living arrangement and social support. Living arrangements were reported as a dichotomous variable living with someone versus living alone. Social support was measured using a modified version of the Arthritis Impact Measurement Scale for Social Support (Meenan, Mason, Anderson, Guccione, & Kazis, 1992). The questions included ‘‘How often did you feel that your family or friends would be around if you needed assistance?,” “How often did you feel that your family or friends were sensitive to your personal needs?,” “How often did you feel that your family or friends were interested in helping you solve problems?,” and “How often did you feel that your family or friends understood how getting older has affected you?,’’ which was modified from “How often did you feel that your family or friends have understood the effects of your arthritis.” Responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale and averaged, with higher scores representing lower levels of perceived social support.

Personal Competencies.—

Cognitive competency was measured using Folstein’s Mini-Mental Status Examination, designed initially as a test of cognition in a hospital setting. The instrument used in this study consists of 30 items capturing yes/no responses and yields scores with a range from 0 to 30. This has been shown to effectively differentiate individuals’ cognitive impairment in clinical, hospital, or community settings (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, 1975). A score of less than 24 is indicative of cognitive impairment and is dichotomized accordingly for analysis.

The Geriatric Depression Scale short form is a 15-item questionnaire used to capture depressive symptomology (Sheikh & Yesavage, 1986), with scores ranging from 0 to 15. Affirmative responses on more than five questions suggest depression in the participant. For analytical purposes, this was coded a dichotomous variable with persons scoring greater than 5 being assigned a value of 1 and all others assigned a value of 0.

Physical competency was measured using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB), which includes timed tests of standing balance, walking, and the ability to rise from a chair (Guralnik et al., 1994). The tests were scored from 0 to 4, with 0 representing inability to perform the task and 4 indicating best performance. The composite scores for the SPPB measure were calculated as the sum of each individual task and ranged from 0 to 12, with higher scores indicating better performance. To be consistent with the environmental press theory’s notions about decreases in competency, the composite scores of the SPPB were reverse coded for analysis so that 0 represented no difficulty with a task and 12 represented inability to perform any tasks, indicating an increase in physical impairment, and hereafter, this will be referred to in that way.

Analytic Technique

Research Question 1.—

The first question, “Are neighborhood environmental characteristics associated with likelihood of nursing home admission for older adults?” was examined initially with Pearson and Spearman correlations of continuous and dichotomous variables to test for potential collinearity, respectively. A logistic regression model was used next to test the relationship between ND and NHA during the period under which participants were being observed (8.5 years), while adjusting for other independent variables and covariates. This approach is consistent with a similar method of using logistic regression to examine event occurrence of cognitive impairment over a finite period of 4.5 years, which was utilized in another large cohort study (Unverzagt et al., 2011).

Furthermore, obtaining the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) is an important first step when modeling nested or clustered data. When the outcome is linear, the value can be interpreted as the percent of variance attributable to the second-level clustering. However, when the outcome is binary, the ICC value is not as easily estimated or interpreted. However, a value that approximates the ICC obtained with a linear outcome is calculable for binary outcomes and was conducted for this study using the SAS Proc Glimmix command. The coefficient is interpreted as the percent of variance in the logit values attributable to clustering in the second level, which in this case is the census tract.

Research Question 2.—

The second question, “Does the level of disadvantage in one’s neighborhood environment affect the level of association with other predictors of NHA?,” was examined using the three levels of disadvantage. Trichotomizing the data into strata labeled high disadvantage (HD), mid disadvantage (MD), and low disadvantage (LD) was done after considering the possible effects of the non-normal distribution of the NDI. Initially models in which the sample was dichotomized at the median value of ND as well as at the mean value were fit, and with each set of outcomes, the main finding—that persons in the higher stratum of ND demonstrated a positive association between physical impairment and NHA was present, while the same relationship did not hold true for persons in the lower disadvantaged stratum. The continuous variables used in the models were tested for differences within strata using analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests, and binary variables were tested for differences with the chi-square statistic. These results are reported in Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants from the UAB Study of Aging

| . | All participants (n = 993) . | Low NDI (n = 330) . | Mid NDI (n = 332) . | High NDI (n = 331) . | p Value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | ||

| Poverty | <.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 340 | 34 | 55 | 17 | 142 | 43 | 143 | 43 | |

| No | 653 | 66 | 275 | 83 | 190 | 57 | 188 | 57 | |

| Age | 75.3 | 7 | 74.6 | 6 | 75.6 | 6 | 75.5 | 7 | .082 |

| Gender | .335 | ||||||||

| Male | 496 | 50 | 174 | 53 | 156 | 47 | 166 | 50 | |

| Female | 497 | 50 | 156 | 47 | 176 | 53 | 165 | 50 | |

| Race | <.001 | ||||||||

| White | 499 | 50 | 251 | 76 | 154 | 46 | 94 | 28 | |

| Black | 494 | 50 | 79 | 24 | 178 | 54 | 237 | 72 | |

| Living arrangement | .024 | ||||||||

| Live with someone | 679 | 68 | 244 | 74 | 214 | 65 | 221 | 67 | |

| Live alone | 314 | 32 | 86 | 26 | 118 | 36 | 110 | 33 | |

| Social support | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | .988 |

| Cognitive status | <.001 | ||||||||

| Cognitively intact | 894 | 90 | 271 | 82 | 216 | 65 | 211 | 64 | |

| Cognitively impaired | 99 | 10 | 59 | 18 | 116 | 35 | 120 | 36 | |

| Depression | .004 | ||||||||

| Not depressed | 698 | 70 | 311 | 94 | 288 | 87 | 295 | 89 | |

| Depressed | 295 | 30 | 19 | 6 | 44 | 13 | 36 | 11 | |

| Physical impairment | 5.1 | 3 | 4.3 | 3 | 5.4 | 3 | 5.7 | 3 | <.001 |

| Nursing home admission | .465 | ||||||||

| Yes | 87 | 9 | 24 | 7 | 33 | 10 | 30 | 9 | |

| No | 906 | 91 | 306 | 93 | 299 | 90 | 301 | 91 | |

| . | All participants (n = 993) . | Low NDI (n = 330) . | Mid NDI (n = 332) . | High NDI (n = 331) . | p Value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | ||

| Poverty | <.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 340 | 34 | 55 | 17 | 142 | 43 | 143 | 43 | |

| No | 653 | 66 | 275 | 83 | 190 | 57 | 188 | 57 | |

| Age | 75.3 | 7 | 74.6 | 6 | 75.6 | 6 | 75.5 | 7 | .082 |

| Gender | .335 | ||||||||

| Male | 496 | 50 | 174 | 53 | 156 | 47 | 166 | 50 | |

| Female | 497 | 50 | 156 | 47 | 176 | 53 | 165 | 50 | |

| Race | <.001 | ||||||||

| White | 499 | 50 | 251 | 76 | 154 | 46 | 94 | 28 | |

| Black | 494 | 50 | 79 | 24 | 178 | 54 | 237 | 72 | |

| Living arrangement | .024 | ||||||||

| Live with someone | 679 | 68 | 244 | 74 | 214 | 65 | 221 | 67 | |

| Live alone | 314 | 32 | 86 | 26 | 118 | 36 | 110 | 33 | |

| Social support | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | .988 |

| Cognitive status | <.001 | ||||||||

| Cognitively intact | 894 | 90 | 271 | 82 | 216 | 65 | 211 | 64 | |

| Cognitively impaired | 99 | 10 | 59 | 18 | 116 | 35 | 120 | 36 | |

| Depression | .004 | ||||||||

| Not depressed | 698 | 70 | 311 | 94 | 288 | 87 | 295 | 89 | |

| Depressed | 295 | 30 | 19 | 6 | 44 | 13 | 36 | 11 | |

| Physical impairment | 5.1 | 3 | 4.3 | 3 | 5.4 | 3 | 5.7 | 3 | <.001 |

| Nursing home admission | .465 | ||||||||

| Yes | 87 | 9 | 24 | 7 | 33 | 10 | 30 | 9 | |

| No | 906 | 91 | 306 | 93 | 299 | 90 | 301 | 91 | |

Baseline Characteristics of Participants from the UAB Study of Aging

| . | All participants (n = 993) . | Low NDI (n = 330) . | Mid NDI (n = 332) . | High NDI (n = 331) . | p Value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | ||

| Poverty | <.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 340 | 34 | 55 | 17 | 142 | 43 | 143 | 43 | |

| No | 653 | 66 | 275 | 83 | 190 | 57 | 188 | 57 | |

| Age | 75.3 | 7 | 74.6 | 6 | 75.6 | 6 | 75.5 | 7 | .082 |

| Gender | .335 | ||||||||

| Male | 496 | 50 | 174 | 53 | 156 | 47 | 166 | 50 | |

| Female | 497 | 50 | 156 | 47 | 176 | 53 | 165 | 50 | |

| Race | <.001 | ||||||||

| White | 499 | 50 | 251 | 76 | 154 | 46 | 94 | 28 | |

| Black | 494 | 50 | 79 | 24 | 178 | 54 | 237 | 72 | |

| Living arrangement | .024 | ||||||||

| Live with someone | 679 | 68 | 244 | 74 | 214 | 65 | 221 | 67 | |

| Live alone | 314 | 32 | 86 | 26 | 118 | 36 | 110 | 33 | |

| Social support | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | .988 |

| Cognitive status | <.001 | ||||||||

| Cognitively intact | 894 | 90 | 271 | 82 | 216 | 65 | 211 | 64 | |

| Cognitively impaired | 99 | 10 | 59 | 18 | 116 | 35 | 120 | 36 | |

| Depression | .004 | ||||||||

| Not depressed | 698 | 70 | 311 | 94 | 288 | 87 | 295 | 89 | |

| Depressed | 295 | 30 | 19 | 6 | 44 | 13 | 36 | 11 | |

| Physical impairment | 5.1 | 3 | 4.3 | 3 | 5.4 | 3 | 5.7 | 3 | <.001 |

| Nursing home admission | .465 | ||||||||

| Yes | 87 | 9 | 24 | 7 | 33 | 10 | 30 | 9 | |

| No | 906 | 91 | 306 | 93 | 299 | 90 | 301 | 91 | |

| . | All participants (n = 993) . | Low NDI (n = 330) . | Mid NDI (n = 332) . | High NDI (n = 331) . | p Value . | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | Mean/ count . | SD/% . | ||

| Poverty | <.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 340 | 34 | 55 | 17 | 142 | 43 | 143 | 43 | |

| No | 653 | 66 | 275 | 83 | 190 | 57 | 188 | 57 | |

| Age | 75.3 | 7 | 74.6 | 6 | 75.6 | 6 | 75.5 | 7 | .082 |

| Gender | .335 | ||||||||

| Male | 496 | 50 | 174 | 53 | 156 | 47 | 166 | 50 | |

| Female | 497 | 50 | 156 | 47 | 176 | 53 | 165 | 50 | |

| Race | <.001 | ||||||||

| White | 499 | 50 | 251 | 76 | 154 | 46 | 94 | 28 | |

| Black | 494 | 50 | 79 | 24 | 178 | 54 | 237 | 72 | |

| Living arrangement | .024 | ||||||||

| Live with someone | 679 | 68 | 244 | 74 | 214 | 65 | 221 | 67 | |

| Live alone | 314 | 32 | 86 | 26 | 118 | 36 | 110 | 33 | |

| Social support | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | 6.1 | 3 | .988 |

| Cognitive status | <.001 | ||||||||

| Cognitively intact | 894 | 90 | 271 | 82 | 216 | 65 | 211 | 64 | |

| Cognitively impaired | 99 | 10 | 59 | 18 | 116 | 35 | 120 | 36 | |

| Depression | .004 | ||||||||

| Not depressed | 698 | 70 | 311 | 94 | 288 | 87 | 295 | 89 | |

| Depressed | 295 | 30 | 19 | 6 | 44 | 13 | 36 | 11 | |

| Physical impairment | 5.1 | 3 | 4.3 | 3 | 5.4 | 3 | 5.7 | 3 | <.001 |

| Nursing home admission | .465 | ||||||||

| Yes | 87 | 9 | 24 | 7 | 33 | 10 | 30 | 9 | |

| No | 906 | 91 | 306 | 93 | 299 | 90 | 301 | 91 | |

Finally, logistic regression analysis was performed for each stratum to examine how people living within different levels of disadvantage respond to factors hypothesized to be associated with NHA. Analyses for this study were conducted using SAS 9.3 and SPSS version 12.0.

Results

Table 1 presents baseline characteristics of all participants and of individuals by the ND strata. Over the 8.5 years in the study, 87 people (9%) experienced NHA. The mean age of the sample at baseline was 75.3. Women comprised 50% of the sample; and blacks comprised 50%; 32% of persons were living alone. The mean score of social support was 3.1. Cognitive impairment was present in 10% of the sample at baseline, and depression was present in 30% of the sample. Finally, the mean physical impairment score was 5.2.

Also included in Table 1 are the stratum-specific descriptive statistics for the sample, with results of ANOVA and chi-square tests for differences in the strata. There are no significant differences in proportions of NHA, the dependent variable, for the three groups. Among the three strata, poverty, race, prevalence of persons living alone, prevalence of persons with cognitive impairment, prevalence of persons with depression, and the mean scores of physical impairment were all significantly different. Finally, the ICC was estimated to be .0068, indicating that less than 1% of the variance in logits is attributable to clustering within census tracts.

Model Set 1

Model Set 1 tested the direct effects of ND adjusting for all factors hypothesized to be associated with NHA (Table 2).

Odds Ratios of Nursing Home Admission (n = 993)

| . | Model 1A . | Model 1B . | Model 1C . | Model 1D . | Model 1E . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suprapersonal | |||||

| NDI | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.07 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Poverty | 1.22 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.09 | |

| Age | 1.10 | 1.08*** | 1.08*** | 1.07 | |

| Gender (female) | 1.38 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.14 | |

| Race (white) | 1.93 | 1.99** | 2.17** | 2.38** | |

| Interpersonal level | |||||

| Living alone | 1.45*** | 2.48*** | 2.41*** | ||

| Social support | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | ||

| Cognitive competency | |||||

| Depression | 1.46 | 1.22 | |||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.38 | 1.25 | |||

| Physical competency | |||||

| Physical impairment | 1.11** | ||||

| Constant | .09*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** |

| Naglekerke R2 | .00 | .09 | .12 | .13 | .14 |

| . | Model 1A . | Model 1B . | Model 1C . | Model 1D . | Model 1E . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suprapersonal | |||||

| NDI | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.07 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Poverty | 1.22 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.09 | |

| Age | 1.10 | 1.08*** | 1.08*** | 1.07 | |

| Gender (female) | 1.38 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.14 | |

| Race (white) | 1.93 | 1.99** | 2.17** | 2.38** | |

| Interpersonal level | |||||

| Living alone | 1.45*** | 2.48*** | 2.41*** | ||

| Social support | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | ||

| Cognitive competency | |||||

| Depression | 1.46 | 1.22 | |||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.38 | 1.25 | |||

| Physical competency | |||||

| Physical impairment | 1.11** | ||||

| Constant | .09*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** |

| Naglekerke R2 | .00 | .09 | .12 | .13 | .14 |

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Odds Ratios of Nursing Home Admission (n = 993)

| . | Model 1A . | Model 1B . | Model 1C . | Model 1D . | Model 1E . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suprapersonal | |||||

| NDI | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.07 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Poverty | 1.22 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.09 | |

| Age | 1.10 | 1.08*** | 1.08*** | 1.07 | |

| Gender (female) | 1.38 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.14 | |

| Race (white) | 1.93 | 1.99** | 2.17** | 2.38** | |

| Interpersonal level | |||||

| Living alone | 1.45*** | 2.48*** | 2.41*** | ||

| Social support | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | ||

| Cognitive competency | |||||

| Depression | 1.46 | 1.22 | |||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.38 | 1.25 | |||

| Physical competency | |||||

| Physical impairment | 1.11** | ||||

| Constant | .09*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** |

| Naglekerke R2 | .00 | .09 | .12 | .13 | .14 |

| . | Model 1A . | Model 1B . | Model 1C . | Model 1D . | Model 1E . |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suprapersonal | |||||

| NDI | 1.03 | 1.10 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.07 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Poverty | 1.22 | 1.27 | 1.15 | 1.09 | |

| Age | 1.10 | 1.08*** | 1.08*** | 1.07 | |

| Gender (female) | 1.38 | 1.13 | 1.19 | 1.14 | |

| Race (white) | 1.93 | 1.99** | 2.17** | 2.38** | |

| Interpersonal level | |||||

| Living alone | 1.45*** | 2.48*** | 2.41*** | ||

| Social support | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.01 | ||

| Cognitive competency | |||||

| Depression | 1.46 | 1.22 | |||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.38 | 1.25 | |||

| Physical competency | |||||

| Physical impairment | 1.11** | ||||

| Constant | .09*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** |

| Naglekerke R2 | .00 | .09 | .12 | .13 | .14 |

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

There were no direct effects of ND on likelihood of NHA in any of the models. In the full model, likelihood of NHA during the 8.5 years of follow-up increased for whites (odds ratio [OR] = 2.38; p < .01), persons living alone (OR = 2.41; p < .001) and with incremental increases in physical impairment (OR = 1.11; p < .01).

Model Set 2

Model Set 2 tests the main effects of individuals’ likelihood of NHA, by neighborhood strata; results for all models are shown in Table 3.

Odds Ratios of Nursing Home Admission Stratified by Neighborhood Disadvantage Strata (n = 993)

| . | Model 2A . | Model 2B . | Model 2C . | Model 2D . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | |

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Poverty | 1.74 | .86 | 1.21 | 2.04 | .83 | 1.40 | 1.72 | .85 | 1.32 | 1.49 | .83 | 3.21 |

| Age | 1.14*** | 1.10** | 1.09** | 1.12** | 1.09** | 1.08** | 1.13** | 1.09** | 1.08** | 1.11 | 1.09* | 1.12 |

| Gender (female) | 2.24 | 2.04** | .66 | 1.99 | 1.63 | .48 | 2.01 | 1.66 | .50 | 2.14 | 1.64 | .39* |

| Race (white) | 2.48 | 3.09 | 1.19 | 3.23 | 2.77* | 1.32 | 3.00 | 3.14** | 1.55 | 3.37 | 3.17* | 1.89 |

| Interpersonal level | ||||||||||||

| Living alone | 2.97* | 2.21* | 2.68* | 2.80* | 2.21* | 2.66* | 2.87* | 2.22* | 2.49* | |||

| Social support | 1.17* | .95 | .96 | 1.15* | .95 | .96 | 1.16* | .95 | .94 | |||

| Cognitive competency | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 4.47* | .68 | 1.49 | 3.50 | .67 | .87 | ||||||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.20 | 1.30 | 1.37 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.13 | ||||||

| Physical competency | ||||||||||||

| Physical impairment | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.24** | |||||||||

| Constant | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** |

| Naglekerke R2 | .16 | .17 | .08 | .22 | .14 | .11 | .26 | .15 | .12 | .27 | .15 | .18 |

| . | Model 2A . | Model 2B . | Model 2C . | Model 2D . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | |

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Poverty | 1.74 | .86 | 1.21 | 2.04 | .83 | 1.40 | 1.72 | .85 | 1.32 | 1.49 | .83 | 3.21 |

| Age | 1.14*** | 1.10** | 1.09** | 1.12** | 1.09** | 1.08** | 1.13** | 1.09** | 1.08** | 1.11 | 1.09* | 1.12 |

| Gender (female) | 2.24 | 2.04** | .66 | 1.99 | 1.63 | .48 | 2.01 | 1.66 | .50 | 2.14 | 1.64 | .39* |

| Race (white) | 2.48 | 3.09 | 1.19 | 3.23 | 2.77* | 1.32 | 3.00 | 3.14** | 1.55 | 3.37 | 3.17* | 1.89 |

| Interpersonal level | ||||||||||||

| Living alone | 2.97* | 2.21* | 2.68* | 2.80* | 2.21* | 2.66* | 2.87* | 2.22* | 2.49* | |||

| Social support | 1.17* | .95 | .96 | 1.15* | .95 | .96 | 1.16* | .95 | .94 | |||

| Cognitive competency | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 4.47* | .68 | 1.49 | 3.50 | .67 | .87 | ||||||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.20 | 1.30 | 1.37 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.13 | ||||||

| Physical competency | ||||||||||||

| Physical impairment | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.24** | |||||||||

| Constant | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** |

| Naglekerke R2 | .16 | .17 | .08 | .22 | .14 | .11 | .26 | .15 | .12 | .27 | .15 | .18 |

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

Odds Ratios of Nursing Home Admission Stratified by Neighborhood Disadvantage Strata (n = 993)

| . | Model 2A . | Model 2B . | Model 2C . | Model 2D . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | |

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Poverty | 1.74 | .86 | 1.21 | 2.04 | .83 | 1.40 | 1.72 | .85 | 1.32 | 1.49 | .83 | 3.21 |

| Age | 1.14*** | 1.10** | 1.09** | 1.12** | 1.09** | 1.08** | 1.13** | 1.09** | 1.08** | 1.11 | 1.09* | 1.12 |

| Gender (female) | 2.24 | 2.04** | .66 | 1.99 | 1.63 | .48 | 2.01 | 1.66 | .50 | 2.14 | 1.64 | .39* |

| Race (white) | 2.48 | 3.09 | 1.19 | 3.23 | 2.77* | 1.32 | 3.00 | 3.14** | 1.55 | 3.37 | 3.17* | 1.89 |

| Interpersonal level | ||||||||||||

| Living alone | 2.97* | 2.21* | 2.68* | 2.80* | 2.21* | 2.66* | 2.87* | 2.22* | 2.49* | |||

| Social support | 1.17* | .95 | .96 | 1.15* | .95 | .96 | 1.16* | .95 | .94 | |||

| Cognitive competency | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 4.47* | .68 | 1.49 | 3.50 | .67 | .87 | ||||||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.20 | 1.30 | 1.37 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.13 | ||||||

| Physical competency | ||||||||||||

| Physical impairment | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.24** | |||||||||

| Constant | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** |

| Naglekerke R2 | .16 | .17 | .08 | .22 | .14 | .11 | .26 | .15 | .12 | .27 | .15 | .18 |

| . | Model 2A . | Model 2B . | Model 2C . | Model 2D . | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | Low . | Mid . | High . | |

| Covariates | ||||||||||||

| Poverty | 1.74 | .86 | 1.21 | 2.04 | .83 | 1.40 | 1.72 | .85 | 1.32 | 1.49 | .83 | 3.21 |

| Age | 1.14*** | 1.10** | 1.09** | 1.12** | 1.09** | 1.08** | 1.13** | 1.09** | 1.08** | 1.11 | 1.09* | 1.12 |

| Gender (female) | 2.24 | 2.04** | .66 | 1.99 | 1.63 | .48 | 2.01 | 1.66 | .50 | 2.14 | 1.64 | .39* |

| Race (white) | 2.48 | 3.09 | 1.19 | 3.23 | 2.77* | 1.32 | 3.00 | 3.14** | 1.55 | 3.37 | 3.17* | 1.89 |

| Interpersonal level | ||||||||||||

| Living alone | 2.97* | 2.21* | 2.68* | 2.80* | 2.21* | 2.66* | 2.87* | 2.22* | 2.49* | |||

| Social support | 1.17* | .95 | .96 | 1.15* | .95 | .96 | 1.16* | .95 | .94 | |||

| Cognitive competency | ||||||||||||

| Depression | 4.47* | .68 | 1.49 | 3.50 | .67 | .87 | ||||||

| Cognitive impairment | 1.20 | 1.30 | 1.37 | 1.13 | 1.25 | 1.13 | ||||||

| Physical competency | ||||||||||||

| Physical impairment | 1.10 | 1.03 | 1.24** | |||||||||

| Constant | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** | .00*** |

| Naglekerke R2 | .16 | .17 | .08 | .22 | .14 | .11 | .26 | .15 | .12 | .27 | .15 | .18 |

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

In this final, stratified model set, age was associated with NHA for persons in the MD stratum (OR = 1.09; p < .05), but not in the LD or HD strata. Women in the HD stratum were less likely to experience NHA (OR = 0.39; p < .05). Being white was significantly associated with likelihood of NHA in the MD stratum (OR = 3.17; p < .05). Within individuals’ personal environments, living alone was associated with NHA for persons in all groups (LD: OR = 2.87; p < .05; MD: OR = 2.22; p < .05; HD: OR = 2.49; p < .05). Also lower levels of social support was a significant predictor of NHA for persons in the LD stratum (OR = 1.16; p < .05). Finally, only in the HD stratum was physical impairment associated with NHA (OR = 1.24; p < .01).

In sum, these findings show that for persons in all strata, living alone increased likelihood of NHA. Lack of social support may increase the likelihood of NHA for persons in the LD stratum. Additionally, for persons in the MD strata, age and being white were associated with increased likelihood of NHA. Finally, in the HD strata being a woman and an increase in physical impairment were associated with NHA.

Discussion

The neighborhood environment is important, particularly for special ecological actors such as older adults (Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2000; Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2010; Lawton & Nahemow, 1973). Whether ND independently or directly influences an older adult’s likelihood of NHA was evaluated in this study. Additionally, we examined whether, depending on the level of ND, there are differences in the stressors leading older adults to enter a nursing home.

The findings from the first set of models, designed to test the effects of ND on likelihood of NHA, demonstrated no association between the NDI and likelihood of NHA (Table 2). Because disadvantaged neighborhoods often have limited formal services and frequently are characterized by low social cohesion (Ross & Mirowsky, 2001), it was anticipated that the effects of living in a disadvantaged neighborhood would directly affect one’s likelihood of NHA. However, this clearly was not the case. Because the causes of NHA may not be rooted in the neighborhood itself but in other factors associated with the effects of disadvantaged and disordered places, the second set of models wherein the sample was stratified by levels of ND was analyzed to assess differences in likelihood of NHA based on the strata in which the individuals were placed.

Model Set 2 (Table 3), in which the data were stratified by ND into three groups by low, mid and high disadvantage characteristics allowed the same covariates to be tested within each of those strata. In the stratified, full set of models, age was associated with NHA for persons in the MD stratum; however, it was not significant in the LD or HD strata. Also of note for this stratified model, race appeared to matter only for the MD group. Women living in high disadvantaged neighborhoods were less likely to experience NHA as compared with men. Living alone was associated with NHA across strata, and lower levels of perceived social support appeared to be significant only for persons in the LD stratum. Finally, and perhaps the most important finding of this study is that for older adults in the HD stratum, physical impairment was associated with NHA but not for persons in other strata. Specifically for a person in the HD stratum, the likelihood of NHA increased 24% for every point of increase in physical impairment. Thus, it is not so much that ND has a direct effect on NHA, but that experiencing physical impairment in highly disadvantaged neighborhoods may lead to NHA because of individuals’ inability to navigate through those spaces to get the assistance needed to age in place.

Implications

The needs of older adults, whose numbers will continue to increase in the United States over the coming decades, are of great concern because as individuals age, they require more health care and supportive services. Because much of the care that they need can be offered in the community rather than in formal medical settings like nursing homes, it is imperative that factors potentially affecting the location of care delivery be explored. This research has shown that individuals’ neighborhood environment is associated with NHA in accordance with the environmental press theory, namely that older adults are particularly susceptible to the effects of the neighborhood characteristics around them.

Theoretical Implications.—

This study linked two theoretical perspectives—the social ecological literature from gerontology and the ND literature from sociology—in a new and unique way. Lawton particularly raised the profile of older adults as unique ecological actors and highlighted the fact that as individuals begin to experience physical and cognitive decline, they become more reliant on the environment around them (Lawton & Nahemow, 1973; Lawton & Simon, 1968). The ND literature demonstrated more broadly, the mechanisms whereby environmental characteristics affect individuals’ health and health behaviors.

Linking these theoretical perspectives to the research questions posed in this manuscript has the potential to provide further theoretical explanation of the impact of environmental factors, like neighborhood effects, on quality of life and health services utilization, specifically, NHA. The relationship between one’s ecology or environment and their quality of life has been explored for several decades now, and it is known to be an important factor in the well-being of individuals; however, the way in which the environmental context works in tandem with individual-level factors has not yet been fully explained.

The more recent ND literature has shown that neighborhoods can be a source of either risk or resources for residents (Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2010). Attempts to measure ND have yielded concise variable sets and formulas that make creating an NDI relatively simple and still very meaningful. This has led to a vast body of research showing that place really does matter for health (Krieger et al., 2003). No one known to these authors before now has linked Lawton’s environmental press theory with the ND literature. This present study represents a novel approach to quantitatively assessing the characteristics of environments, particularly what Lawton described as the suprapersonal environment.

Although findings from these analyses do not provide definitive support for Lawton’s theory that older adults at risk of being unable to handle increasing physical and cognitive challenges are more influenced by the disadvantaged neighborhood environments, they certainly provide some support for that notion. This was demonstrated by the analyses in Model Set 2 where older adults in the highly disadvantaged neighborhood stratum appeared to be sensitive to physical impairments while older adults in other strata were not sensitive to the same physical impairments as a factor increasing their likelihood of NHA.

Although there were no direct effects of ND on likelihood of NHA, significant findings among the stratified sample are perhaps more theoretically meaningful and provide researchers with a new application of Lawton’s work on the environment (Lawton, 1983; Lawton & Hoover, 1981; Lawton & Nahemow, 1973; Lawton & Simon, 1968; Lawton et al., 1982) alongside the expansive literature on ND (Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2000; Fitzpatrick & LaGory, 2010; Ross & Mirowsky, 2001; Wilson, 2011).

The second theoretical implication is centered on a new use of Lawton’s theory for examining outcomes. Lawton’s work was largely theoretical, and though it has been used to examine outcomes on occasion, the theory has not been used previously to develop and test hypotheses about the relationship between environmental factors and likelihood of NHA. A theoretically derived model linking the characteristics of persons’ neighborhood environment where people live with their individual characteristics to explore the likelihood of NHA is a new and important application with policy implications.

Policy Implications.—

Individuals and corporations entrusted with designing community and individual interventions for older adults should benefit from knowing about the relationship between environmental factors and NHA. For corporate organizations or companies who deliver home- and community-based interventions, findings which show that characteristics of spaces where people live matters for likelihood of NHA could be important in tailoring interventions according to characteristics of the neighborhoods where they are situated. Furthermore, these findings may be helpful for health insurance companies who make decisions about what types of services to reimburse as they may consider funding for services based on the characteristics of the places where their clients and customers live. For instance, certain interventions included in the range of home- and community-based services may be considered more important for persons living in disadvantaged neighborhood environments than for persons living in less disadvantaged spaces.

Additionally, government policy around health care delivery should be adjusted to account for individuals’ neighborhood environment. The most direct way to do this is by focusing on the unique needs of people living in disadvantaged neighborhood environments, and perhaps, by more generally directing interventions toward neighborhoods that are disadvantaged. However, addressing the relationship between neighborhood environmental characteristics and NHA does not just require focusing on health-specific interventions. Rather, focusing on housing policy may also be important. The Department of Housing and Urban Development has spaces designated for older adults in poverty. These facilities are frequently located in low income, high disadvantage areas, so extra interventions may be needed in these spaces to counteract the nature of the neighborhoods. Directing funds to improve housing may be a way to enable older adults in these neighborhoods to remain in their communities longer and avert costly nursing home care.

Summary of Implications.—

In sum, these findings provide greater theoretical clarity on the role of neighborhood environment for likelihood of NHA and point to the need for focused efforts directed at older adults living in disadvantaged neighborhood environments. There is significant value in the care offered in the nursing home, but directing services to older adults through home- and community-based services may drive costs of care down and meet the desires of patients who wish to age in place. Because the overall health care costs of older adults will continue to rise, and interventions that allow for them to remain in the home would likely save money for their families, insurance companies, and the government, efforts to tailor interventions to specific contexts are recommended.

Limitations

As with all research, this study has limitations. The data set used did not have enough participants in each census tract to fit hierarchical logistic models, which would have been a more ideal approach to assessing how much variance in likelihood of NHA is actually attributable to the neighborhood environment. Some tracts contained as few as one participant, and to be able to adequately detect the effects of the neighborhood, as few as five cases and possibly as many as 10 cases would be needed in each census tract with a minimum of 50 second-level units (Hox, 2010; Kreft, 1996). In addition, the UAB SOA data lack measures that would be helpful in effectively assessing individuals’ actual social support and networks in addition to the perceived support variable that we do capture. Finally, we are also unable to report on individual perceptions of the neighborhood (suprapersonal) environment and are limited to the data available from the census on their objective characteristics.

Future Research

Future work on related research questions should use larger databases that allow multilevel modeling and geographic information systems (GIS) mapping techniques to be applied to the data. Also, analytic techniques such as survival analysis would answer questions about timing of NHA and improve the analysis.

Furthermore, additional description and validation of the theoretical connection between Lawton’s conceptualization of the suprapersonal environment and the more recent literature on ND is warranted. Additional work on the policy implications of this work is also in order. Finally, the supply-side factors of nursing homes may be important and should be considered in future work. Namely, the question, “Do where and in what types of neighborhoods nursing homes are located, as well as their distance to potential residents, impact individuals’ likelihood of nursing home admission?” should be addressed. This could be done with GIS, but data to answer these questions were not available for this study.

Conclusion

Older adults are unique ecological actors and are especially susceptible to the effects of their environment. This study is an important first step in assessing the specific effects of neighborhood environments on likelihood of NHA. Understanding what factors affect NHA, including characteristics of neighborhoods, is important because these factors may indicate areas where interventions are warranted. Addressing NHA is imperative because of the rising costs of health care, specifically long-term care, and future research should focus on other ways that ND affects older adults with larger data sets and more robust methods.

Funding

Dr. Buys’ work is supported in part by T32 HS013852.

This study was funded in part by grant numbers R01-AG015062, P30AG031054, and 5UL1 RR025777 from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the policy of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

Acknowledgments

D.R.B. conceptualized and implemented this research. C.A.B. provided statistical expertise and guidance for the project. P.D. lent expertise on general issues of social gerontology, gender and the design of the project. M.E.L. contributed to the theoretical framework, namely the integration of Lawton’s Environmental Press theory with the neighborhood disadvantage literature. P.S. gave insight into the Study of Aging database and provided feedback on the theoretical aspects of the study. R.M.A. is the principal investigator of the UAB Study of Aging and contributed to the discussion of predictors of nursing home admission. R.K. contributed to the review and revisions of the paper and contributed to the statistical analysis. J.L.L. provided insight into the conceptualization of the project and to the implications of the findings, particularly the policy implications.

References

Author notes

Decision Editor: Rachel Pruchno, PhD