-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

N.M. van den Boogaard, A.J. Bensdorp, K. Oude Rengerink, K. Barnhart, S. Bhattacharya, I.M. Custers, C. Coutifaris, A.J. Goverde, D.S. Guzick, E.C. Hughes, P. Factor-Litvak, P. Steures, P.G.A. Hompes, F. van der Veen, B.W.J. Mol, P. Bossuyt, Prognostic profiles and the effectiveness of assisted conception: secondary analyses of individual patient data, Human Reproduction Update, Volume 20, Issue 1, January/February 2014, Pages 141–151, https://doi.org/10.1093/humupd/dmt035

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

At present, it is unclear which treatment strategy is best for couples with unexplained or mild male subfertility. We hypothesized that the prognostic profile influences the effectiveness of assisted conception. We addressed this issue by analysing individual patient data (IPD) from randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

We performed an IPD analysis of published RCTs on treatment strategies for subfertile couples. Eligible studies were identified from Cochrane systematic reviews and we also searched Medline and EMBASE. The authors of RCTs that compared expectant management (EM), intracervical insemination (ICI), intrauterine insemination (IUI), all three with or without controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) and IVF in couples with unexplained or male subfertility, and had reported live birth or ongoing pregnancy as an outcome measure, were invited to share their data. For each individual patient the chance of natural conception was calculated with a validated prognostic model. We constructed prognosis-by-treatment curves and tested whether there was a significant interaction between treatment and prognosis.

We acquired data from 8 RCTs, including 2550 couples. In three studies (n = 954) the more invasive treatment strategies tended to be less effective in couples with a high chance of natural conception but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P-value for interaction between prognosis and treatment outcome were 0.71, 0.31 and 0.19). In one study (n = 932 couples) the strategies with COS (ICI and IUI) led to higher pregnancy rates than unstimulated strategies (ICI 8% versus 15%, IUI 13% versus 22%), regardless of prognosis (P-value for interaction in all comparisons >0.5), but at the expense of a high twin rate in the COS strategies (ICI 6% versus 23% and IUI 3% versus 30%, respectively). In two studies (n = 373 couples), the more invasive treatment strategies tended to be more effective in couples with a good prognosis but this difference did not reach statistical significance (P-value for interaction: 0.38 and 0.68). In one study (n = 253 couples) the differential effect of prognosis on treatment effect was limited (P-value for interaction 0.52), perhaps because prognosis was incorporated in the inclusion criteria. The only study that compared EM with IVF included 38 couples, too small for a precise estimate.

In this IPD analysis of couples with unexplained or male subfertility, we did not find a large differential effect of prognosis on the effectiveness of fertility treatment with IUI, COS or IVF.

Introduction

Despite the frequent use of fertility enhancing treatments in couples with unexplained or male subfertility, evidence from randomized trials is scarce. Most international guidelines recommend starting with less invasive treatments, for example intrauterine insemination (IUI), and moving on to more aggressive interventions, such as IVF, if these are unsuccessful or when the woman is older and the duration of subfertility is longer (ESHRE, 2001; NICE, 2004; The Practice Committe of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine, 2012).

Data from randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are contradictory and sometimes counterintuitive (Soliman et al., 1993; Guzick et al., 1999; Goverde et al., 2000; Hughes et al., 2004; Steures et al., 2006; Bhattacharya et al., 2008; Reindollar et al., 2009). These studies do not provide a clear recommendation on which couple would benefit from which treatment. For example, in a comparison between IUI and expectant management (EM) there is a non-significant beneficial effect for IUI (odds ratio: 1.53 confidence interval (CI): 0.91–2.56) (Bhattacharya et al., 2008), while in another comparison between IUI with controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) and EM there is no significant beneficial effect for IUI with COS (risk ratio (RR):0.85 CI: 0.55–1.30) (Steures et al., 2006). In studies that compared IVF with EM one showed a significant beneficial effect of IVF over EM (RR 4.5, CI 1.44–14.6) (Hughes et al., 2004), while another found a non-significant beneficial effect of EM (RR: 2.7 CI: 0.97–7.49) (Soliman et al., 1993). Several meta-analyses have pooled the results of these RCTs and also did not find convincing benefits of one treatment strategy over the other (Verhulst et al., 2006; Bensdorp et al., 2007; Steures et al., 2008; Veltman-Verhulst et al., 2012). A possible explanation for this may be the inclusion of couples with varying prognostic profiles as evident from the wide range in female age and duration of subfertility within RCTs, which results in different chances of natural conception. When conventional meta-analyses are inconclusive or contradictory and the trials included are heterogeneous, individual patient data (IPD) analysis can have additional value, because factors influencing the outcome (in this case prognosis) can be taken into account in the analysis. As such, IPD is an extension of standard meta-analysis and may create new possibilities for evaluating treatments and treatment policies. In the Netherlands, standard treatment policy is to use the prognostic profile of a subfertile couple to select couples for EM. In the present IPD analysis we wanted to evaluate whether this prognostic profile can be used to select couples for a specific treatment, such as IUI with or without COS or IVF. We evaluated whether the treatment effects in the RCTs are influenced by the prognostic profile of the couples. We hypothesized that invasive treatments, such as IUI with COS or IVF, are more effective than EM in couples with limited chances of natural conception, but less so in couples with good prospects of natural conception. To test our hypothesis, we performed an IPD analysis of published RCTs, and evaluated whether a couples' prognosis of natural conception attenuated or strengthened the impact of assisted reproduction.

Methods

We performed an IPD analysis of published RCTs on treatment strategies for subfertile couples. The protocol has been published previously (van den Boogaard et al., 2012). This study is registered in PROSPERO (registration number CRD42011001832) and the study protocol of this study is published in the BJOG.

Selection of studies

We selected studies in couples who had been trying to conceive for at least 1 year, were diagnosed with unexplained, male or cervical factor subfertility and who had never received COS, IUI or IVF in the past. Unexplained subfertility was defined as subfertility without any demonstrable cause after the basic fertility work up, including tests of ovulation, semen analysis and tubal evaluation. Mild endometriosis and one-sided tubal pathology were also categorized as unexplained subfertility. For the definition of male subfertility the World Health Organization criteria of 2009 were used (Cooper et al., 2010). The prognostic model used in our analysis includes the motility of the sperm as a predictor. This allows us to be liberal in the inclusion of studies with male subfertility. Cervical factor subfertility was defined as the absence of progressive motile spermatozoa in cervical mucus, with normal semen parameters.

RCTs were eligible if they had compared two or more of the following strategies: EM, timed intercourse with or without COS, IUI with or without COS and IVF, and if they had reported live birth or ongoing pregnancy as an outcome measure.

We included only truly RCTs. Quasi-randomized studies, where allocation relied on alternation or chart number, were not eligible. In case of a crossover design the authors were asked for the pre-crossover data.

Eligible studies were identified based on Cochrane systematic reviews of studies comparing EM, intra-cervical insemination (ICI) or IUI with and without COS and IVF in couples with unexplained, male or cervical factor subfertility (Helmerhorst et al., 2005; Pandian et al., 2005; Verhulst et al., 2006; Bensdorp et al., 2007; Steures et al., 2008). We additionally searched Medline and EMBASE to detect trials published after closure of the data collection of the Cochrane reviews. We used the following search terms (with synonyms and closely related words): ‘infertility’, ‘subfecundity’, ‘unexplained subfertility’, ‘male subfertility’, ‘cervical factor’, ‘intrauterine insemination’ ‘intrauterine insemination with COS’ and ‘in vitro fertilization’. We did not apply language restrictions. The final search was performed in January 2011. References were checked and authors of relevant studies were contacted to ask whether they were aware of any unpublished ongoing studies.

Collection of individual patient data (IPD)

For each eligible study, we tried to obtain contact information of the first author from Medline, EMBASE or from searching the Internet. We invited authors by email to share their data. If contact information of the first author was unavailable or when the first author did not respond after two or more emails, we contacted the second or last author.

We provided authors who were considering participation with a more detailed study proposal and asked authors to send us their complete database in original format, to minimize their efforts to select the appropriate variables or to convert data into a specific format. If variables and categories were not adequately labelled, a separate data dictionary was requested. The data received were crosschecked against published reports of the study. Authors were contacted for clarification in case of discrepancies and asked to supply any missing data when possible.

Data extraction

From each trial, we extracted information on the characteristics of the couples: female age, duration, type and cause of subfertility, previous miscarriages, percentage motile sperm, sperm concentration, grade of endometriosis, tubal patency, referral status, BMI, number of treatment cycles, number of follicles ≥16 mm during IUI, dose of gonadotrophins, number of embryos transferred; and the type of outcome, i.e. live birth, ongoing pregnancy and multiple birth.

Assessment of study quality

Assessment of the methodological quality of included studies was based on the information reported in the original published papers and responses to specific queries to the authors. We assessed the risk of bias assessed by checking the adequacy of randomization, comparability of groups at baseline, the completeness of follow-up and a priori sample size estimation. Generalizability was based on the description of the sample recruited. The adequacy of randomization was assessed by checking methods used for sequence generation, treatment allocation and allocation concealment. When these details were unclear in the initial publication, we contacted authors to provide further clarification.

Analysis

For every RCT we calculated the chances of natural conception leading to live birth within 12 months for each participating couple, using the validated prognostic model developed by Hunault et al. (2004). This model takes into account female age, duration of subfertility, subfertility being primary or secondary, percentage of motile sperm and being referred by a general practitioner or gynaecologist. Missing data were multiply imputed within each original dataset, using all prognostic factors and the outcome.

Using logistic regression, we estimated the probability of live birth for each couple based on the Hunault score, the treatment allocation and the interaction between the Hunault score and the treatment allocation. This interaction term explores the relation between the Hunault score and the treatment outcome. We evaluated the statistical significance of this interaction term with the Wald test statistic, using a conventional significance level of P < 0.05. If live birth was not registered, ongoing pregnancy was used.

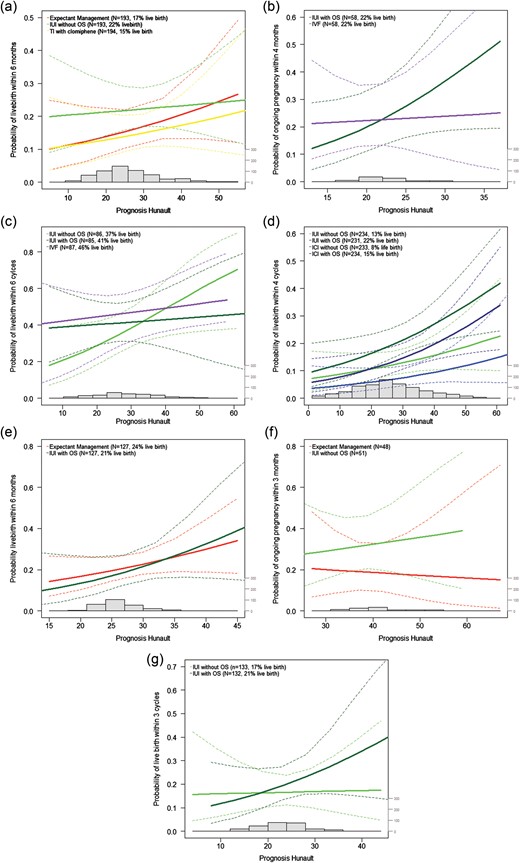

We also graphically presented the regression model. We used a prognosis-by-treatment curve, similar to the marker-by-treatment predictiveness curves proposed by Janes et al. (2011). These graphs display for each treatment arm the probability of a live birth over the range of Hunault prognoses. When a differential benefit from treatment is present, the curves intersect: on the left side of the intersection the treatment line on top results in a higher number of live births, at the intersection point both treatments result in the same number of live births, which then switches, and on the right side of the intersection the other treatment is favourable and results in a higher number of live births.

If heterogeneity allows, the original data will be merged into a single set and the abovementioned analyses will be performed for the merged data set as well.

Data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences 18.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical approval

We used anonymized data. The Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Centre in Amsterdam indicated that formal approval of an ethics committee was not required. Ethical approval to share trial data was obtained by participating trial groups in their centres if necessary.

Results

Study selection

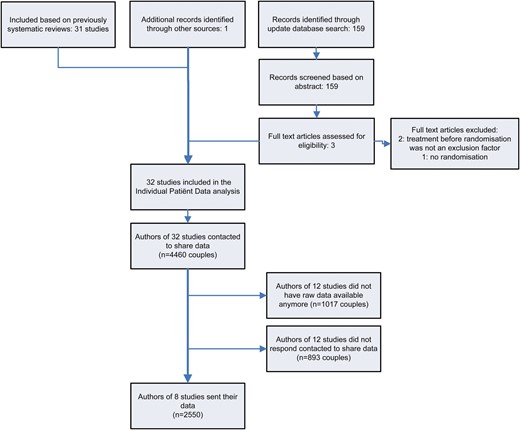

The systematic literature search and the results of the data sharing requests are summarized in a flowchart (Fig. 1). From previously published systematic reviews, 31 studies were selected as eligible. The additional literature search yielded 159 citations. Three full text manuscripts were further evaluated for eligibility, but all had to be excluded for different reasons (Tummon et al., 1997; Streda et al., 2007; Reindollar et al., 2009). One, not yet published study was included via co-authors of included studies (Custers et al., 2011). The authors of 32 eligible studies, containing 4.460 couples in total, were invited to share their IPD (Table I). Authors of 12 studies did not have the original data available (Ho et al., 1989, 1992; te Velde et al., 1989; Martinez et al., 1990; Crosignani et al., 1991; Murdoch et al., 1991; Crosignani and Walters, 1994; Nan et al., 1994; Aribarg and Sukcharoen, 1995; Chung et al., 1995; Cohlen et al., 1998; Agarwal and Mittal, 2004). The authors of 12 other studies did not respond to two or more emails (Kerin et al., 1984; Glazener et al., 1987; Kerin and Quinn, 1987; Deaton et al., 1990; Kirby et al., 1991; Karlstrom et al., 1993; Arici et al., 1994; Melis et al., 1995; Arcaini et al., 1996; Gregoriou et al., 1996; Janko et al., 1998; Jaroudi et al., 1998). Eventually, the authors of 8 of the 32 eligible studies contributed their data, containing data for 2550 of the total 4460 eligible couples. These eight studies were included in this IPD analysis (Guzick et al., 1999; Goverde et al., 2000; Hughes et al., 2004; Steures et al., 2006, 2007a, b; Bhattacharya et al., 2008; Custers et al., 2011).

Eligible studies.

| . | Authors . | Publication year . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agarwal and Mittal | 2004 |

| 2 | Arcaini et al. | 1996 |

| 3 | Aribarg and Sukcharoen | 1995 |

| 4 | Bhattacharya et al. | 2008 |

| 5 | Chung et al. | 1995 |

| 6 | Cohlen et al. | 1998 |

| 7 | Crosignani and Walters | 1994 |

| 8 | Crosignani et al. | 1991 |

| 9 | Custers et al. | 2011 |

| 10 | Deaton et al. | 1990 |

| 11 | Glazener et al. | 1987 |

| 12 | Goverde et al. | 2000 |

| 13 | Gregoriou et al. | 1996 |

| 14 | Guzick et al. | 1999 |

| 15 | Ho et al. | 1989 |

| 16 | Ho et al. | 1992 |

| 17 | Hughes et al. | 2004 |

| 18 | Janko et al. | 1998 |

| 19 | Jaroudi et al. | 1998 |

| 20 | Karlstrom et al. | 1993 |

| 21 | Kerin et al. | 1984 |

| 22 | Kerin and Quinn | 1987 |

| 23 | Kirby et al. | 1991 |

| 24 | Martinez et al. | 1990 |

| 25 | Melis et al. | 1995 |

| 26 | Murdoch et al. | 1991 |

| 27 | Nan et al. | 1994 |

| 28 | Soliman et al. | 1993 |

| 29 | Steures et al. | 2006 |

| 30 | Steures et al. | 2007a, b |

| 31 | Steures et al. | 2007a, b |

| 32 | te Velde et al. | 1989 |

| . | Authors . | Publication year . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agarwal and Mittal | 2004 |

| 2 | Arcaini et al. | 1996 |

| 3 | Aribarg and Sukcharoen | 1995 |

| 4 | Bhattacharya et al. | 2008 |

| 5 | Chung et al. | 1995 |

| 6 | Cohlen et al. | 1998 |

| 7 | Crosignani and Walters | 1994 |

| 8 | Crosignani et al. | 1991 |

| 9 | Custers et al. | 2011 |

| 10 | Deaton et al. | 1990 |

| 11 | Glazener et al. | 1987 |

| 12 | Goverde et al. | 2000 |

| 13 | Gregoriou et al. | 1996 |

| 14 | Guzick et al. | 1999 |

| 15 | Ho et al. | 1989 |

| 16 | Ho et al. | 1992 |

| 17 | Hughes et al. | 2004 |

| 18 | Janko et al. | 1998 |

| 19 | Jaroudi et al. | 1998 |

| 20 | Karlstrom et al. | 1993 |

| 21 | Kerin et al. | 1984 |

| 22 | Kerin and Quinn | 1987 |

| 23 | Kirby et al. | 1991 |

| 24 | Martinez et al. | 1990 |

| 25 | Melis et al. | 1995 |

| 26 | Murdoch et al. | 1991 |

| 27 | Nan et al. | 1994 |

| 28 | Soliman et al. | 1993 |

| 29 | Steures et al. | 2006 |

| 30 | Steures et al. | 2007a, b |

| 31 | Steures et al. | 2007a, b |

| 32 | te Velde et al. | 1989 |

Eligible studies.

| . | Authors . | Publication year . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agarwal and Mittal | 2004 |

| 2 | Arcaini et al. | 1996 |

| 3 | Aribarg and Sukcharoen | 1995 |

| 4 | Bhattacharya et al. | 2008 |

| 5 | Chung et al. | 1995 |

| 6 | Cohlen et al. | 1998 |

| 7 | Crosignani and Walters | 1994 |

| 8 | Crosignani et al. | 1991 |

| 9 | Custers et al. | 2011 |

| 10 | Deaton et al. | 1990 |

| 11 | Glazener et al. | 1987 |

| 12 | Goverde et al. | 2000 |

| 13 | Gregoriou et al. | 1996 |

| 14 | Guzick et al. | 1999 |

| 15 | Ho et al. | 1989 |

| 16 | Ho et al. | 1992 |

| 17 | Hughes et al. | 2004 |

| 18 | Janko et al. | 1998 |

| 19 | Jaroudi et al. | 1998 |

| 20 | Karlstrom et al. | 1993 |

| 21 | Kerin et al. | 1984 |

| 22 | Kerin and Quinn | 1987 |

| 23 | Kirby et al. | 1991 |

| 24 | Martinez et al. | 1990 |

| 25 | Melis et al. | 1995 |

| 26 | Murdoch et al. | 1991 |

| 27 | Nan et al. | 1994 |

| 28 | Soliman et al. | 1993 |

| 29 | Steures et al. | 2006 |

| 30 | Steures et al. | 2007a, b |

| 31 | Steures et al. | 2007a, b |

| 32 | te Velde et al. | 1989 |

| . | Authors . | Publication year . |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agarwal and Mittal | 2004 |

| 2 | Arcaini et al. | 1996 |

| 3 | Aribarg and Sukcharoen | 1995 |

| 4 | Bhattacharya et al. | 2008 |

| 5 | Chung et al. | 1995 |

| 6 | Cohlen et al. | 1998 |

| 7 | Crosignani and Walters | 1994 |

| 8 | Crosignani et al. | 1991 |

| 9 | Custers et al. | 2011 |

| 10 | Deaton et al. | 1990 |

| 11 | Glazener et al. | 1987 |

| 12 | Goverde et al. | 2000 |

| 13 | Gregoriou et al. | 1996 |

| 14 | Guzick et al. | 1999 |

| 15 | Ho et al. | 1989 |

| 16 | Ho et al. | 1992 |

| 17 | Hughes et al. | 2004 |

| 18 | Janko et al. | 1998 |

| 19 | Jaroudi et al. | 1998 |

| 20 | Karlstrom et al. | 1993 |

| 21 | Kerin et al. | 1984 |

| 22 | Kerin and Quinn | 1987 |

| 23 | Kirby et al. | 1991 |

| 24 | Martinez et al. | 1990 |

| 25 | Melis et al. | 1995 |

| 26 | Murdoch et al. | 1991 |

| 27 | Nan et al. | 1994 |

| 28 | Soliman et al. | 1993 |

| 29 | Steures et al. | 2006 |

| 30 | Steures et al. | 2007a, b |

| 31 | Steures et al. | 2007a, b |

| 32 | te Velde et al. | 1989 |

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in Table II. The studies varied in inclusion criteria, duration of the interventions, controlled ovarian stimulation protocols, starting dose and criteria for cancellation of insemination. The controlled ovarian stimulation protocols and the number of embryos transferred varied in the different IVF arms. Six studies registered live births per couple (Guzick et al., 1999; Goverde et al., 2000; Hughes et al., 2004; Steures et al., 2006, 2007a; Bhattacharya et al., 2008), whereas the other two studies only reported ongoing pregnancy (Steures et al., 2007b; Custers et al., 2011). All studies registered multiple births, which ranged from 0 to 100%.

Study characteristics.

| Study . | Population Inclusion criteria . | Intervention . | Outcome . | Quality features . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) (n = 193 versus 193 versus 194) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility or mild endometriosis with at least 2 years of infertility Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and bilateral tubal patency Semen: minimum motility of 20% | Expectant management IUI without COS Timed intercourse with COS, starting dose: 50 mg Clomiphene citrate/day Cancel criteria: ≥3 follicles in 1st cycle Duration 6 months | Live birth Expectant management 17% IUI without COS 14% Timed intercourse with COS 23% Multiple birth Expectant management 1% IUI without COS 0.5% Timed intercourse with COS 0.5% | Power calculation: yes Randomization telephone randomization system Trial design: parallel Multicentre: 5 centres ITT-analysis: yes Three arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Custers et al. (2011) (n = 58 versus 58) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility and an unfavourable prognosis of natural conception (≤30% according model of Hunaulta) Female age: ≤37 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: total motility count of ≥3 × 106 | IUI with COS, mean dose 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm IVF-eSET, starting dose 100–150 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist. ET: elective single embryo transfer in case of good quality embryo's Duration 4 months | Live birth IUI with COS 21% IVF eSET 22% Multiple birth IUI with COS 25% IVF eSET 14% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated randomization Trial design: parallel Multi centre ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Goverde et al. (2000) (n = 86 versus 85 versus 87) | Unexplained for at least 3 years or male subfertility for at least 1 year (including couples with stage I or II treated endometriosis) Female age: 18–38 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: >20 million progressively motile spermatozoa in ejaculate in unexplained subfertility, in male subfertility <20 million progressively motile spermatozoa in ejaculate and ≥600.000 progressively motile spermatozoa after Percoll processing | IUI without COS. Timing IUI: 20–30 h after LH surge IUI with COS, starting dose 75 IU/day FSH Cancel criteria: >3 follicles of ≥18 mm or >6 follicles of ≥14 mm IVF, starting dose 150–225 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist ET: 48–72 h after retrieval, 2–3 embryo's Duration 6 cycles (max) | Live birth IUI without COS 29% IUI with COS 36% IVF 28% Multiple birth IUI without COS 4% IUI with COS 29% IVF 21% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated randomization schedule in sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Single centre ITT-analysis: yes Three arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Guzick et al. (1999) (n = 233 versus 234 versus 234 versus 231) | Unexplained or male subfertility and couples with stage I or II treated endometriosis Female age: ≤40 years Basic fertility work up: regular cycle normal uterine cavity and pelvis Semen: any motile sperm | ICI without COS Timing: day after urinary LH- surge IUI without COS Timing: day after urinary LH-surge ICI + COS, starting dose 150 IU FSH/day, cancel: E2 > 3000 pg/ml IUI + COS, starting dose 150 IU FSH/day, cancel: E2 > 3000 pg/ml Duration 4 cycles (max) | Live birth ICI without COS 8% IUI without COS 13% ICI with COS 15% IUI with COS 22% Multiple birth ICI without COS 6% IUI without COS 3% ICI with COS 23% IUI with COS 30% | Power calculation: no Randomization computer generated permuted block in locked files Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 10 clinics ITT-analysis: not possible Four arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Hughes et al. (2004) (n = 20 versus 18) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility or with mild endometriosis and with at least 2 years of infertility Female age: 18–39 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: adequate to perform ICSI | Expectant managementb IVF, starting dose 150–225 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist ET: mean number of embryo's transferred: 2 and maximum 4 Duration 3 months | Live birth Expectant management 1% IVF 22% Multiple birth Expectant management 100% IVF 25% | Power calculation: yes Randomization opaque sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2006) (n = 127 versus 126) | Unexplained subfertility and an intermediate prognosis (30–40%a) Female age: ≤37 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: normal | Expectant management IUI with COS, mean dose 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm Duration 6 months | Live birth: Expectant management: 24% IUI with COS: 21% Multiple birth Expectant management: 3% IUI with COS: 7% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 26 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2007a) (n = 136 versus 136) | Abnormal PCT due to cervical factor or male factor and a poor prognosis (≤30%a) Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion and a negative PCTc Semen: normal or mild male factor | IUI without COS Timing: 20–30 h after LH-surge or 36–40 h after hCG IUI with COS, mean 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm Duration: max 3 cycles | Live birth IUI without COS 17% IUI with COS 21% Multiple birth IUI without COS 5% IUI with COS 7% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 24 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2007b) (n = 52 versus 49) | Couples with an isolated cervical factor and a good prognosis (≥30%a) Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up normal, semen normal or one-sided tubal occlusion and a negative PCT Semen: normal | IUI without COS Timing: 20–30 h after LH-surge or 36–40 h after hCG After 3 failed cycles, IUI with COS was givenc Expectant management Duration 3 months | Live birth: Expectant management: 19% IUI without COS: 31% Multiple pregnancies: Expectant management: 0% IUI without COS: 6% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 17 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Study . | Population Inclusion criteria . | Intervention . | Outcome . | Quality features . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) (n = 193 versus 193 versus 194) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility or mild endometriosis with at least 2 years of infertility Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and bilateral tubal patency Semen: minimum motility of 20% | Expectant management IUI without COS Timed intercourse with COS, starting dose: 50 mg Clomiphene citrate/day Cancel criteria: ≥3 follicles in 1st cycle Duration 6 months | Live birth Expectant management 17% IUI without COS 14% Timed intercourse with COS 23% Multiple birth Expectant management 1% IUI without COS 0.5% Timed intercourse with COS 0.5% | Power calculation: yes Randomization telephone randomization system Trial design: parallel Multicentre: 5 centres ITT-analysis: yes Three arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Custers et al. (2011) (n = 58 versus 58) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility and an unfavourable prognosis of natural conception (≤30% according model of Hunaulta) Female age: ≤37 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: total motility count of ≥3 × 106 | IUI with COS, mean dose 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm IVF-eSET, starting dose 100–150 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist. ET: elective single embryo transfer in case of good quality embryo's Duration 4 months | Live birth IUI with COS 21% IVF eSET 22% Multiple birth IUI with COS 25% IVF eSET 14% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated randomization Trial design: parallel Multi centre ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Goverde et al. (2000) (n = 86 versus 85 versus 87) | Unexplained for at least 3 years or male subfertility for at least 1 year (including couples with stage I or II treated endometriosis) Female age: 18–38 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: >20 million progressively motile spermatozoa in ejaculate in unexplained subfertility, in male subfertility <20 million progressively motile spermatozoa in ejaculate and ≥600.000 progressively motile spermatozoa after Percoll processing | IUI without COS. Timing IUI: 20–30 h after LH surge IUI with COS, starting dose 75 IU/day FSH Cancel criteria: >3 follicles of ≥18 mm or >6 follicles of ≥14 mm IVF, starting dose 150–225 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist ET: 48–72 h after retrieval, 2–3 embryo's Duration 6 cycles (max) | Live birth IUI without COS 29% IUI with COS 36% IVF 28% Multiple birth IUI without COS 4% IUI with COS 29% IVF 21% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated randomization schedule in sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Single centre ITT-analysis: yes Three arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Guzick et al. (1999) (n = 233 versus 234 versus 234 versus 231) | Unexplained or male subfertility and couples with stage I or II treated endometriosis Female age: ≤40 years Basic fertility work up: regular cycle normal uterine cavity and pelvis Semen: any motile sperm | ICI without COS Timing: day after urinary LH- surge IUI without COS Timing: day after urinary LH-surge ICI + COS, starting dose 150 IU FSH/day, cancel: E2 > 3000 pg/ml IUI + COS, starting dose 150 IU FSH/day, cancel: E2 > 3000 pg/ml Duration 4 cycles (max) | Live birth ICI without COS 8% IUI without COS 13% ICI with COS 15% IUI with COS 22% Multiple birth ICI without COS 6% IUI without COS 3% ICI with COS 23% IUI with COS 30% | Power calculation: no Randomization computer generated permuted block in locked files Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 10 clinics ITT-analysis: not possible Four arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Hughes et al. (2004) (n = 20 versus 18) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility or with mild endometriosis and with at least 2 years of infertility Female age: 18–39 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: adequate to perform ICSI | Expectant managementb IVF, starting dose 150–225 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist ET: mean number of embryo's transferred: 2 and maximum 4 Duration 3 months | Live birth Expectant management 1% IVF 22% Multiple birth Expectant management 100% IVF 25% | Power calculation: yes Randomization opaque sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2006) (n = 127 versus 126) | Unexplained subfertility and an intermediate prognosis (30–40%a) Female age: ≤37 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: normal | Expectant management IUI with COS, mean dose 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm Duration 6 months | Live birth: Expectant management: 24% IUI with COS: 21% Multiple birth Expectant management: 3% IUI with COS: 7% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 26 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2007a) (n = 136 versus 136) | Abnormal PCT due to cervical factor or male factor and a poor prognosis (≤30%a) Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion and a negative PCTc Semen: normal or mild male factor | IUI without COS Timing: 20–30 h after LH-surge or 36–40 h after hCG IUI with COS, mean 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm Duration: max 3 cycles | Live birth IUI without COS 17% IUI with COS 21% Multiple birth IUI without COS 5% IUI with COS 7% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 24 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2007b) (n = 52 versus 49) | Couples with an isolated cervical factor and a good prognosis (≥30%a) Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up normal, semen normal or one-sided tubal occlusion and a negative PCT Semen: normal | IUI without COS Timing: 20–30 h after LH-surge or 36–40 h after hCG After 3 failed cycles, IUI with COS was givenc Expectant management Duration 3 months | Live birth: Expectant management: 19% IUI without COS: 31% Multiple pregnancies: Expectant management: 0% IUI without COS: 6% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 17 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

aThe chance of natural conception within 12 months.

bCouples who received treatment of IUI with or without clomifene or FSH before randomization were excluded for this individual patient data (IPD) analysis.

cThe stimulated cycles are not included in this IPD analysis.

COS, controlled ovarian stimulation; ET, embryo transfer; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; ITT, intention to treat; IUI, intra uterine insemination; PCT, post coital test; SET, single embryo transfer.

Study characteristics.

| Study . | Population Inclusion criteria . | Intervention . | Outcome . | Quality features . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) (n = 193 versus 193 versus 194) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility or mild endometriosis with at least 2 years of infertility Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and bilateral tubal patency Semen: minimum motility of 20% | Expectant management IUI without COS Timed intercourse with COS, starting dose: 50 mg Clomiphene citrate/day Cancel criteria: ≥3 follicles in 1st cycle Duration 6 months | Live birth Expectant management 17% IUI without COS 14% Timed intercourse with COS 23% Multiple birth Expectant management 1% IUI without COS 0.5% Timed intercourse with COS 0.5% | Power calculation: yes Randomization telephone randomization system Trial design: parallel Multicentre: 5 centres ITT-analysis: yes Three arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Custers et al. (2011) (n = 58 versus 58) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility and an unfavourable prognosis of natural conception (≤30% according model of Hunaulta) Female age: ≤37 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: total motility count of ≥3 × 106 | IUI with COS, mean dose 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm IVF-eSET, starting dose 100–150 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist. ET: elective single embryo transfer in case of good quality embryo's Duration 4 months | Live birth IUI with COS 21% IVF eSET 22% Multiple birth IUI with COS 25% IVF eSET 14% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated randomization Trial design: parallel Multi centre ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Goverde et al. (2000) (n = 86 versus 85 versus 87) | Unexplained for at least 3 years or male subfertility for at least 1 year (including couples with stage I or II treated endometriosis) Female age: 18–38 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: >20 million progressively motile spermatozoa in ejaculate in unexplained subfertility, in male subfertility <20 million progressively motile spermatozoa in ejaculate and ≥600.000 progressively motile spermatozoa after Percoll processing | IUI without COS. Timing IUI: 20–30 h after LH surge IUI with COS, starting dose 75 IU/day FSH Cancel criteria: >3 follicles of ≥18 mm or >6 follicles of ≥14 mm IVF, starting dose 150–225 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist ET: 48–72 h after retrieval, 2–3 embryo's Duration 6 cycles (max) | Live birth IUI without COS 29% IUI with COS 36% IVF 28% Multiple birth IUI without COS 4% IUI with COS 29% IVF 21% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated randomization schedule in sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Single centre ITT-analysis: yes Three arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Guzick et al. (1999) (n = 233 versus 234 versus 234 versus 231) | Unexplained or male subfertility and couples with stage I or II treated endometriosis Female age: ≤40 years Basic fertility work up: regular cycle normal uterine cavity and pelvis Semen: any motile sperm | ICI without COS Timing: day after urinary LH- surge IUI without COS Timing: day after urinary LH-surge ICI + COS, starting dose 150 IU FSH/day, cancel: E2 > 3000 pg/ml IUI + COS, starting dose 150 IU FSH/day, cancel: E2 > 3000 pg/ml Duration 4 cycles (max) | Live birth ICI without COS 8% IUI without COS 13% ICI with COS 15% IUI with COS 22% Multiple birth ICI without COS 6% IUI without COS 3% ICI with COS 23% IUI with COS 30% | Power calculation: no Randomization computer generated permuted block in locked files Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 10 clinics ITT-analysis: not possible Four arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Hughes et al. (2004) (n = 20 versus 18) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility or with mild endometriosis and with at least 2 years of infertility Female age: 18–39 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: adequate to perform ICSI | Expectant managementb IVF, starting dose 150–225 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist ET: mean number of embryo's transferred: 2 and maximum 4 Duration 3 months | Live birth Expectant management 1% IVF 22% Multiple birth Expectant management 100% IVF 25% | Power calculation: yes Randomization opaque sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2006) (n = 127 versus 126) | Unexplained subfertility and an intermediate prognosis (30–40%a) Female age: ≤37 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: normal | Expectant management IUI with COS, mean dose 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm Duration 6 months | Live birth: Expectant management: 24% IUI with COS: 21% Multiple birth Expectant management: 3% IUI with COS: 7% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 26 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2007a) (n = 136 versus 136) | Abnormal PCT due to cervical factor or male factor and a poor prognosis (≤30%a) Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion and a negative PCTc Semen: normal or mild male factor | IUI without COS Timing: 20–30 h after LH-surge or 36–40 h after hCG IUI with COS, mean 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm Duration: max 3 cycles | Live birth IUI without COS 17% IUI with COS 21% Multiple birth IUI without COS 5% IUI with COS 7% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 24 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2007b) (n = 52 versus 49) | Couples with an isolated cervical factor and a good prognosis (≥30%a) Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up normal, semen normal or one-sided tubal occlusion and a negative PCT Semen: normal | IUI without COS Timing: 20–30 h after LH-surge or 36–40 h after hCG After 3 failed cycles, IUI with COS was givenc Expectant management Duration 3 months | Live birth: Expectant management: 19% IUI without COS: 31% Multiple pregnancies: Expectant management: 0% IUI without COS: 6% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 17 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Study . | Population Inclusion criteria . | Intervention . | Outcome . | Quality features . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) (n = 193 versus 193 versus 194) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility or mild endometriosis with at least 2 years of infertility Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and bilateral tubal patency Semen: minimum motility of 20% | Expectant management IUI without COS Timed intercourse with COS, starting dose: 50 mg Clomiphene citrate/day Cancel criteria: ≥3 follicles in 1st cycle Duration 6 months | Live birth Expectant management 17% IUI without COS 14% Timed intercourse with COS 23% Multiple birth Expectant management 1% IUI without COS 0.5% Timed intercourse with COS 0.5% | Power calculation: yes Randomization telephone randomization system Trial design: parallel Multicentre: 5 centres ITT-analysis: yes Three arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Custers et al. (2011) (n = 58 versus 58) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility and an unfavourable prognosis of natural conception (≤30% according model of Hunaulta) Female age: ≤37 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: total motility count of ≥3 × 106 | IUI with COS, mean dose 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm IVF-eSET, starting dose 100–150 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist. ET: elective single embryo transfer in case of good quality embryo's Duration 4 months | Live birth IUI with COS 21% IVF eSET 22% Multiple birth IUI with COS 25% IVF eSET 14% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated randomization Trial design: parallel Multi centre ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Goverde et al. (2000) (n = 86 versus 85 versus 87) | Unexplained for at least 3 years or male subfertility for at least 1 year (including couples with stage I or II treated endometriosis) Female age: 18–38 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: >20 million progressively motile spermatozoa in ejaculate in unexplained subfertility, in male subfertility <20 million progressively motile spermatozoa in ejaculate and ≥600.000 progressively motile spermatozoa after Percoll processing | IUI without COS. Timing IUI: 20–30 h after LH surge IUI with COS, starting dose 75 IU/day FSH Cancel criteria: >3 follicles of ≥18 mm or >6 follicles of ≥14 mm IVF, starting dose 150–225 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist ET: 48–72 h after retrieval, 2–3 embryo's Duration 6 cycles (max) | Live birth IUI without COS 29% IUI with COS 36% IVF 28% Multiple birth IUI without COS 4% IUI with COS 29% IVF 21% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated randomization schedule in sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Single centre ITT-analysis: yes Three arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Guzick et al. (1999) (n = 233 versus 234 versus 234 versus 231) | Unexplained or male subfertility and couples with stage I or II treated endometriosis Female age: ≤40 years Basic fertility work up: regular cycle normal uterine cavity and pelvis Semen: any motile sperm | ICI without COS Timing: day after urinary LH- surge IUI without COS Timing: day after urinary LH-surge ICI + COS, starting dose 150 IU FSH/day, cancel: E2 > 3000 pg/ml IUI + COS, starting dose 150 IU FSH/day, cancel: E2 > 3000 pg/ml Duration 4 cycles (max) | Live birth ICI without COS 8% IUI without COS 13% ICI with COS 15% IUI with COS 22% Multiple birth ICI without COS 6% IUI without COS 3% ICI with COS 23% IUI with COS 30% | Power calculation: no Randomization computer generated permuted block in locked files Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 10 clinics ITT-analysis: not possible Four arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Hughes et al. (2004) (n = 20 versus 18) | Couples with unexplained or male subfertility or with mild endometriosis and with at least 2 years of infertility Female age: 18–39 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: adequate to perform ICSI | Expectant managementb IVF, starting dose 150–225 IU/day FSH with GnRH agonist ET: mean number of embryo's transferred: 2 and maximum 4 Duration 3 months | Live birth Expectant management 1% IVF 22% Multiple birth Expectant management 100% IVF 25% | Power calculation: yes Randomization opaque sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2006) (n = 127 versus 126) | Unexplained subfertility and an intermediate prognosis (30–40%a) Female age: ≤37 years Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion Semen: normal | Expectant management IUI with COS, mean dose 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm Duration 6 months | Live birth: Expectant management: 24% IUI with COS: 21% Multiple birth Expectant management: 3% IUI with COS: 7% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 26 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2007a) (n = 136 versus 136) | Abnormal PCT due to cervical factor or male factor and a poor prognosis (≤30%a) Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up: confirmed ovulation and no or one-sided tubal occlusion and a negative PCTc Semen: normal or mild male factor | IUI without COS Timing: 20–30 h after LH-surge or 36–40 h after hCG IUI with COS, mean 75 IU FSH/day (range 37–150) Cancel: 3 follicles ≥16 mm, or 5 follicles ≥12 mm Duration: max 3 cycles | Live birth IUI without COS 17% IUI with COS 21% Multiple birth IUI without COS 5% IUI with COS 7% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 24 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

| Steures et al. (2007b) (n = 52 versus 49) | Couples with an isolated cervical factor and a good prognosis (≥30%a) Female age: no age limit Basic fertility work up normal, semen normal or one-sided tubal occlusion and a negative PCT Semen: normal | IUI without COS Timing: 20–30 h after LH-surge or 36–40 h after hCG After 3 failed cycles, IUI with COS was givenc Expectant management Duration 3 months | Live birth: Expectant management: 19% IUI without COS: 31% Multiple pregnancies: Expectant management: 0% IUI without COS: 6% | Power calculation: yes Randomization computer generated in balanced blocks, sealed envelopes Trial design: parallel Multi centre, 17 centres ITT-analysis: yes Two arms comparable at baseline: yes Follow-up >80%: yes |

aThe chance of natural conception within 12 months.

bCouples who received treatment of IUI with or without clomifene or FSH before randomization were excluded for this individual patient data (IPD) analysis.

cThe stimulated cycles are not included in this IPD analysis.

COS, controlled ovarian stimulation; ET, embryo transfer; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; ITT, intention to treat; IUI, intra uterine insemination; PCT, post coital test; SET, single embryo transfer.

One study compared IUI with and without COS with ICI with or without COS. ICI was considered as a surrogate for intercourse or EM in this study (Guzick et al., 1999).

Some of the data on two studies could not be included: in one study 101 couples had received other treatments (COS or IUI) before randomization; these couples were excluded from the analysis (Hughes et al., 2004). In another study couples started with three cycles of IUI without COS. If those three cycles failed, subsequent IUI cycles were performed with COS (Steures et al., 2007b). We only included the first three cycles of IUI without COS reported in this study.

Assessment of study quality

The methodological quality of included studies is summarized in the last column of Table II. Of the eight included studies (Guzick et al., 1999), all had performed a power calculation. All reported adequate methods of randomization and concealment of allocation. All studies had a parallel design and all studies except one (Goverde et al., 2000) were multicentre studies. In all studies the randomized groups were comparable at baseline and had a follow-up of at least 80%. Comparison of the data received from authors with the published results revealed only minimal differences in duration of subfertility, which were ignored. The quality of the data received was considered satisfactory for all included studies. There were no missing data.

Interaction between prognosis and efficacy of treatment

The chance of a natural conception within 12 months was calculated for all included couples based on the variables in the datasets (Hunault et al., 2004). For the variables female age, duration of subfertility, subfertility being primary or secondary and sperm motility, there were no missing data. In four studies (Guzick et al., 1999; Goverde et al., 2000; Hughes et al., 2004; Bhattacharya et al., 2008) the datasets did not include a variable concerning the referral status (secondary or tertiary care), but based on the context of the publication or after contacting the author, we categorized all couples in these four studies as secondary care patients. The prognosis of natural conception is summarized in Table III. The mean prognosis was comparable between treatment arms in the included trials and the standard deviation of prognosis varied from 5.3 and 13.9%.

The prognosis, the chance of natural conception within 12 months according to the prognostic model of Hunault.

| Study . | Mean prognosis according to the model of Hunault (SD) . |

|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) | Expectant management, 30.1% (9.4) |

| IUI, 30.3% (10.1) | |

| Timed intercourse with COS, 29.5% (9.4) | |

| Custers et al. (2011) | IUI-COS, 20.8% (6.8) |

| IVF eSET, 20.7% (5.4) | |

| Goverde et al. (2000) | IUI without COS, 25.5% (10.2) |

| IUI-COS, 24.4% (10.8) | |

| IVF, 24.2% (12.0) | |

| Guzick et al. (1999) | ICI without COS, 29.6% (13.3) |

| IUI without COS, 28.2% (12.7) | |

| ICI- COS, 29.9% (12.6) | |

| IUI- COS, 29.5% (12.4) | |

| Hughes et al. (2004) | Expectant management, 22.7% (13.9) |

| IVF, 24.1% (10.6) | |

| Steures et al. (2006) | Expectant management, 28.7% (6.0) |

| IUI-COS, 28.6% (5.3) | |

| Steures et al. (2007a) | IUI without COS, 23.4% (6.9) |

| IUI-COS, 24.1% (6.2) | |

| Steures et al. (2007b) | Expectant management, 39.3% (8.5) |

| IUI without COS, 37.0% (8.2) |

| Study . | Mean prognosis according to the model of Hunault (SD) . |

|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) | Expectant management, 30.1% (9.4) |

| IUI, 30.3% (10.1) | |

| Timed intercourse with COS, 29.5% (9.4) | |

| Custers et al. (2011) | IUI-COS, 20.8% (6.8) |

| IVF eSET, 20.7% (5.4) | |

| Goverde et al. (2000) | IUI without COS, 25.5% (10.2) |

| IUI-COS, 24.4% (10.8) | |

| IVF, 24.2% (12.0) | |

| Guzick et al. (1999) | ICI without COS, 29.6% (13.3) |

| IUI without COS, 28.2% (12.7) | |

| ICI- COS, 29.9% (12.6) | |

| IUI- COS, 29.5% (12.4) | |

| Hughes et al. (2004) | Expectant management, 22.7% (13.9) |

| IVF, 24.1% (10.6) | |

| Steures et al. (2006) | Expectant management, 28.7% (6.0) |

| IUI-COS, 28.6% (5.3) | |

| Steures et al. (2007a) | IUI without COS, 23.4% (6.9) |

| IUI-COS, 24.1% (6.2) | |

| Steures et al. (2007b) | Expectant management, 39.3% (8.5) |

| IUI without COS, 37.0% (8.2) |

COS, controlled ovarian stimulation; IUI, intrauterine insemination; SET, single embryo transfer.

The prognosis, the chance of natural conception within 12 months according to the prognostic model of Hunault.

| Study . | Mean prognosis according to the model of Hunault (SD) . |

|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) | Expectant management, 30.1% (9.4) |

| IUI, 30.3% (10.1) | |

| Timed intercourse with COS, 29.5% (9.4) | |

| Custers et al. (2011) | IUI-COS, 20.8% (6.8) |

| IVF eSET, 20.7% (5.4) | |

| Goverde et al. (2000) | IUI without COS, 25.5% (10.2) |

| IUI-COS, 24.4% (10.8) | |

| IVF, 24.2% (12.0) | |

| Guzick et al. (1999) | ICI without COS, 29.6% (13.3) |

| IUI without COS, 28.2% (12.7) | |

| ICI- COS, 29.9% (12.6) | |

| IUI- COS, 29.5% (12.4) | |

| Hughes et al. (2004) | Expectant management, 22.7% (13.9) |

| IVF, 24.1% (10.6) | |

| Steures et al. (2006) | Expectant management, 28.7% (6.0) |

| IUI-COS, 28.6% (5.3) | |

| Steures et al. (2007a) | IUI without COS, 23.4% (6.9) |

| IUI-COS, 24.1% (6.2) | |

| Steures et al. (2007b) | Expectant management, 39.3% (8.5) |

| IUI without COS, 37.0% (8.2) |

| Study . | Mean prognosis according to the model of Hunault (SD) . |

|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) | Expectant management, 30.1% (9.4) |

| IUI, 30.3% (10.1) | |

| Timed intercourse with COS, 29.5% (9.4) | |

| Custers et al. (2011) | IUI-COS, 20.8% (6.8) |

| IVF eSET, 20.7% (5.4) | |

| Goverde et al. (2000) | IUI without COS, 25.5% (10.2) |

| IUI-COS, 24.4% (10.8) | |

| IVF, 24.2% (12.0) | |

| Guzick et al. (1999) | ICI without COS, 29.6% (13.3) |

| IUI without COS, 28.2% (12.7) | |

| ICI- COS, 29.9% (12.6) | |

| IUI- COS, 29.5% (12.4) | |

| Hughes et al. (2004) | Expectant management, 22.7% (13.9) |

| IVF, 24.1% (10.6) | |

| Steures et al. (2006) | Expectant management, 28.7% (6.0) |

| IUI-COS, 28.6% (5.3) | |

| Steures et al. (2007a) | IUI without COS, 23.4% (6.9) |

| IUI-COS, 24.1% (6.2) | |

| Steures et al. (2007b) | Expectant management, 39.3% (8.5) |

| IUI without COS, 37.0% (8.2) |

COS, controlled ovarian stimulation; IUI, intrauterine insemination; SET, single embryo transfer.

The intercepts, slopes and interaction terms for the treatment strategies in each study are shown in Table IV. To facilitate interpretation, we have integrated the treatment term in the intercepts, and the interaction term in the slope. Differences in the overall treatment effect would then become apparent as a difference in the intercept; differences in the effect of prognosis would show themselves as a difference in slope. The far right column in Table IV shows the P-value to indicate differences in slopes: the interaction between treatment and prognosis. The interaction term was not statistically significant in any of the trials, indicating that there was no evidence of a significant differential effect of prognosis on the efficacy of treatment.

Intercepts, slopes and interaction terms of the treatment strategies per study.

| Study . | Treatment arms . | Intercept (CI) Treatment Effect . | Slope (CI) Prognosis Effect . | P-value interaction Prognosis* treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) (n = 580) | Expectant management | −2.30 (−3.56; −1.04) | 0.023 (−0.021; 0.071) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.42 (−2.50; −0.34) | 0.006 (−0.342; 0.341) | 0.711 | |

| TI with ovarian stimulation | −2.25 (−3.55; −0.92) | 0.017 (−0.025; 0.059) | 0.694 | |

| Custers et al. (2011) (n = 116) | IUI with ovarian stimulation | −3.08 (−5.22; −0.94) | 0.084 (−0.006; 0.174) | Ref |

| IVF | −1.43 (−3.87; 1.03) | 0.009 (−0.105; 0.123) | 0.312 | |

| Goverde et al. (2000) (n = 258) | IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.78 (−2.99; −0.57) | 0.043 (0.003; 0.083) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −0.50 (−1.64; 1.19) | 0.006 (−0.033; 0.045) | 0.190 | |

| IVF | −0.42 (−1.45; 0.61) | 0.010 (−0.025; 0.045) | 0.219 | |

| Guzick et al. (1999) (n = 932) | ICI without ovarian stimulation | −3.28 (−4.55; −2.01) | 0.026 (−0.009; 0.061) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −2.57 (−3.55; −1.57) | 0.022 (−0.007; 0.051) | 0.671 | |

| ICI with ovarian stimulation | −2.82 (−3.86; −1.79) | 0.035 (0.006; 0.064) | 0.878 | |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −2.27 (−3.23; −1.31) | 0.032 (0.006; 0.058) | 0.776 | |

| Steures et al. (2006) (n = 253) | Expectant management | −1.84 (−3.82; 0.15) | 0.023 (−0.043; 0.090) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −3.00 (−5.31; −0.69) | 0.057 (−0.019; 0.133) | 0.517 | |

| Steures et al. (2007a) (n = 272) | IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.696 (−3.32; −0.09) | 0.003 (−0.063; 0.669) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −2.475 (−4.14; −0.79) | 0.045 (−0.021; 0.112) | 0.675 | |

| Steures et al. (2007b) (n = 101) | Expectant management | −1.274 (−4.83; 2.29) | 0.012 (−0.076; 0.100) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −2.775 (−5.78; 0.23) | 0.048 (−0.028; 0.124) | 0.382 |

| Study . | Treatment arms . | Intercept (CI) Treatment Effect . | Slope (CI) Prognosis Effect . | P-value interaction Prognosis* treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) (n = 580) | Expectant management | −2.30 (−3.56; −1.04) | 0.023 (−0.021; 0.071) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.42 (−2.50; −0.34) | 0.006 (−0.342; 0.341) | 0.711 | |

| TI with ovarian stimulation | −2.25 (−3.55; −0.92) | 0.017 (−0.025; 0.059) | 0.694 | |

| Custers et al. (2011) (n = 116) | IUI with ovarian stimulation | −3.08 (−5.22; −0.94) | 0.084 (−0.006; 0.174) | Ref |

| IVF | −1.43 (−3.87; 1.03) | 0.009 (−0.105; 0.123) | 0.312 | |

| Goverde et al. (2000) (n = 258) | IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.78 (−2.99; −0.57) | 0.043 (0.003; 0.083) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −0.50 (−1.64; 1.19) | 0.006 (−0.033; 0.045) | 0.190 | |

| IVF | −0.42 (−1.45; 0.61) | 0.010 (−0.025; 0.045) | 0.219 | |

| Guzick et al. (1999) (n = 932) | ICI without ovarian stimulation | −3.28 (−4.55; −2.01) | 0.026 (−0.009; 0.061) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −2.57 (−3.55; −1.57) | 0.022 (−0.007; 0.051) | 0.671 | |

| ICI with ovarian stimulation | −2.82 (−3.86; −1.79) | 0.035 (0.006; 0.064) | 0.878 | |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −2.27 (−3.23; −1.31) | 0.032 (0.006; 0.058) | 0.776 | |

| Steures et al. (2006) (n = 253) | Expectant management | −1.84 (−3.82; 0.15) | 0.023 (−0.043; 0.090) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −3.00 (−5.31; −0.69) | 0.057 (−0.019; 0.133) | 0.517 | |

| Steures et al. (2007a) (n = 272) | IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.696 (−3.32; −0.09) | 0.003 (−0.063; 0.669) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −2.475 (−4.14; −0.79) | 0.045 (−0.021; 0.112) | 0.675 | |

| Steures et al. (2007b) (n = 101) | Expectant management | −1.274 (−4.83; 2.29) | 0.012 (−0.076; 0.100) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −2.775 (−5.78; 0.23) | 0.048 (−0.028; 0.124) | 0.382 |

IUI, intrauterine insemination; TI, timed intercourse.

Intercepts, slopes and interaction terms of the treatment strategies per study.

| Study . | Treatment arms . | Intercept (CI) Treatment Effect . | Slope (CI) Prognosis Effect . | P-value interaction Prognosis* treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) (n = 580) | Expectant management | −2.30 (−3.56; −1.04) | 0.023 (−0.021; 0.071) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.42 (−2.50; −0.34) | 0.006 (−0.342; 0.341) | 0.711 | |

| TI with ovarian stimulation | −2.25 (−3.55; −0.92) | 0.017 (−0.025; 0.059) | 0.694 | |

| Custers et al. (2011) (n = 116) | IUI with ovarian stimulation | −3.08 (−5.22; −0.94) | 0.084 (−0.006; 0.174) | Ref |

| IVF | −1.43 (−3.87; 1.03) | 0.009 (−0.105; 0.123) | 0.312 | |

| Goverde et al. (2000) (n = 258) | IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.78 (−2.99; −0.57) | 0.043 (0.003; 0.083) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −0.50 (−1.64; 1.19) | 0.006 (−0.033; 0.045) | 0.190 | |

| IVF | −0.42 (−1.45; 0.61) | 0.010 (−0.025; 0.045) | 0.219 | |

| Guzick et al. (1999) (n = 932) | ICI without ovarian stimulation | −3.28 (−4.55; −2.01) | 0.026 (−0.009; 0.061) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −2.57 (−3.55; −1.57) | 0.022 (−0.007; 0.051) | 0.671 | |

| ICI with ovarian stimulation | −2.82 (−3.86; −1.79) | 0.035 (0.006; 0.064) | 0.878 | |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −2.27 (−3.23; −1.31) | 0.032 (0.006; 0.058) | 0.776 | |

| Steures et al. (2006) (n = 253) | Expectant management | −1.84 (−3.82; 0.15) | 0.023 (−0.043; 0.090) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −3.00 (−5.31; −0.69) | 0.057 (−0.019; 0.133) | 0.517 | |

| Steures et al. (2007a) (n = 272) | IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.696 (−3.32; −0.09) | 0.003 (−0.063; 0.669) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −2.475 (−4.14; −0.79) | 0.045 (−0.021; 0.112) | 0.675 | |

| Steures et al. (2007b) (n = 101) | Expectant management | −1.274 (−4.83; 2.29) | 0.012 (−0.076; 0.100) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −2.775 (−5.78; 0.23) | 0.048 (−0.028; 0.124) | 0.382 |

| Study . | Treatment arms . | Intercept (CI) Treatment Effect . | Slope (CI) Prognosis Effect . | P-value interaction Prognosis* treatment . |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhattacharya et al. (2008) (n = 580) | Expectant management | −2.30 (−3.56; −1.04) | 0.023 (−0.021; 0.071) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.42 (−2.50; −0.34) | 0.006 (−0.342; 0.341) | 0.711 | |

| TI with ovarian stimulation | −2.25 (−3.55; −0.92) | 0.017 (−0.025; 0.059) | 0.694 | |

| Custers et al. (2011) (n = 116) | IUI with ovarian stimulation | −3.08 (−5.22; −0.94) | 0.084 (−0.006; 0.174) | Ref |

| IVF | −1.43 (−3.87; 1.03) | 0.009 (−0.105; 0.123) | 0.312 | |

| Goverde et al. (2000) (n = 258) | IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.78 (−2.99; −0.57) | 0.043 (0.003; 0.083) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −0.50 (−1.64; 1.19) | 0.006 (−0.033; 0.045) | 0.190 | |

| IVF | −0.42 (−1.45; 0.61) | 0.010 (−0.025; 0.045) | 0.219 | |

| Guzick et al. (1999) (n = 932) | ICI without ovarian stimulation | −3.28 (−4.55; −2.01) | 0.026 (−0.009; 0.061) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −2.57 (−3.55; −1.57) | 0.022 (−0.007; 0.051) | 0.671 | |

| ICI with ovarian stimulation | −2.82 (−3.86; −1.79) | 0.035 (0.006; 0.064) | 0.878 | |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −2.27 (−3.23; −1.31) | 0.032 (0.006; 0.058) | 0.776 | |

| Steures et al. (2006) (n = 253) | Expectant management | −1.84 (−3.82; 0.15) | 0.023 (−0.043; 0.090) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −3.00 (−5.31; −0.69) | 0.057 (−0.019; 0.133) | 0.517 | |

| Steures et al. (2007a) (n = 272) | IUI without ovarian stimulation | −1.696 (−3.32; −0.09) | 0.003 (−0.063; 0.669) | Ref |

| IUI with ovarian stimulation | −2.475 (−4.14; −0.79) | 0.045 (−0.021; 0.112) | 0.675 | |

| Steures et al. (2007b) (n = 101) | Expectant management | −1.274 (−4.83; 2.29) | 0.012 (−0.076; 0.100) | Ref |

| IUI without ovarian stimulation | −2.775 (−5.78; 0.23) | 0.048 (−0.028; 0.124) | 0.382 |

IUI, intrauterine insemination; TI, timed intercourse.

Prognosis by treatment curves

The prognosis-by-treatment curves are shown in Fig. 2a–g. To facilitate interpretation of the curves we discuss four studies in more detail. The curve for the trial of Bhattacharya et al. (2008) is shown in Fig. 2a. Most couples had a probability between 20 and 30% of conceiving naturally within 12 months. With all three treatment strategies the probability of live birth increased with a better prognosis of natural conception. In couples with a poor prognosis of natural conception the probability of live birth was higher for those treated with IUI without COS compared with EM and timed intercourse with clomiphene citrate (CC). In couples with a prognosis of natural conception of more than 50%, the probability of live birth was higher in couples who received EM. In couples receiving only CC the probability of live birth was lower in all couples, regardless of prognosis. The slopes of all three lines in the curve differ, but as shown in Table IV, this difference did not reach statistical significance (interaction IUI and EM P = 0.711 and interaction CC and EM P = 0.694).

In the study of Custers et al. (2011) (Fig. 2b) the probability of ongoing pregnancy also seems to differ between the two treatment strategies. The curve shows a higher probability of ongoing pregnancy in couples with a poor prognosis of natural conception when treated with IVF. In couples with a good prognosis of natural conception the probability of ongoing pregnancy was higher if they received IUI with COS. This difference in slope did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.312, Table IV).

The prognosis-by-treatment curves of the study of Goverde et al. (2000) (Fig. 2c) show that in couples with a poor prognosis the probability of live birth is higher in couples treated with IUI with COS and IVF compared with couples treated with IUI without COS. In couples with a good prognosis the predicted probability of live birth is higher in couples who received IUI without COS. This difference in slope did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.190 and 0.219, Table IV).

In the study of Guzick et al. (1999) ICI in a natural cycle (n = 233) and in a stimulated cycle (n = 234) were compared with IUI in a natural cycle (n = 234) and in a stimulated cycle (n = 231), in couples with unexplained subfertility or male subfertility. The prognosis-by-treatment curves (Fig. 2d) show a higher predicted probability of live birth in all couples treated with IUI or ICI with COS. In this study prognosis does not help in differentiating between treatment options. All interaction terms between prognosis and treatment in this study were not significant (P = 0.617, P = 0.878, P = 0.776, Table IV).

The trends of the curves of the two other studies can be observed in Fig. 2e and f. We did not plot curves for the study of Hughes et al. (2004) which compared IVF (n = 18) with EM (n = 20) because after excluding the couples who received treatment before randomization, the number of included couples was too small to draw a reliable curve.

To compare the prognostic marker female age with the Hunault score on the effectiveness of assisted conception we also plotted female age-by-treatment curves for all studies (data not shown). Age appeared to be a poorer predictor than the Hunault score.

The heterogeneity in treatment protocols precluded the use of meta-analysis and the benefits of increased precision from pooling data.

Discussion

Currently, there is no consensus on the best treatment strategy for couples with unexplained or mild male subfertility. In this study we explored the possibility of using prognosis of natural conception to select the best treatment strategy for these couples. We collected data from 8 primary studies including 2550 couples, almost 60% of all treatment-naïve couples ever randomized between EM, IUI or IVF and published. Our results showed that the probability of live birth or ongoing pregnancy tended to be higher with a better prognosis of natural conception but we were unable to confirm a statistically significant differential effect of prognosis of natural conception on treatment efficacy.

A major strength of this study is that we were able to collect data for almost 60% of all couples ever randomized in studies evaluating the efficacy of EM, TI, ICI or IUI with or without COS and IVF in couples without a major cause for their unfulfilled child wish. Authors of 12 studies did not have their data anymore and authors of another 12 studies could not be traced: overall these studies were older, which explains why it was harder to trace the data or the author. Untraceable studies were relatively small and the majority of these studies had a crossover design. The studies that we included in this IPD analysis were the largest ones, the most recent ones and also those of high quality.

The importance of patient selection based on prognosis of natural conception has been stressed before and validated prognostic models estimating the chances of treatment independent, i.e. natural conception are available (Collins et al., 1983; Leushuis et al., 2009). In an impact study of the prognostic model of Hunault, couples with an intermediate prognosis were randomly allocated to EM or IUI with COS, both for 6 months. The live birth rates in both groups were comparable, suggesting that couples with an intermediate or a poor prognosis are better off with EM (Steures et al., 2006). The present study aimed to confirm an association between prognostic profiles and the efficacy of assisted conception, but failed to find a significant effect of prognosis on treatment outcome.

One explanation for our negative findings may be differences in stimulation protocol and embryo transfer policies between the included studies which may override the impact of patient profile. Especially in the treatment arms of IUI with COS, higher dosage of controlled ovarian stimulation and milder cancellation criteria are not only associated with higher pregnancy rates but also higher risks of multiple pregnancies. For example, treatment of IUI with COS for six cycles resulted in one study in a live birth of 36% and multiple birth rate of 29% (Goverde et al., 2000) compared with the same treatment for 6 months in another study with a live birth rate of 21% and a multiple pregnancy rate of 7% (Steures et al., 2006). At the moment most countries find multiple birth rates of 29% not acceptable (ESHRE position paper, 2008), as multiple births are associated with higher morbidity and mortality rates for both mother and child compared with singleton pregnancies (Helmerhorst et al., 2004; Gerris, 2005). This high multiple birth rate reduces the applicability of the results of our study and also of the original study (Guzick et al., 1999): unfortunately this is the largest RCT performed in this field (n = 932). This issue emphasizes the need for more large RCTs evaluating the efficacy of IUI and IVF for couples with unexplained or male subfertility.

Our results indicate that the effect rate of IUI COS is largely correlated with twin rates. Our results question the impact of prognostic profile on the efficacy of IUI COS, implicating that the treatment effect is also limited in poor prognosis couples. Consequently, acceptable pregnancy rates in these couples are only achieved through a high multiple pregnancy rate. We should keep in mind here that studies reported on, at maximum, 6 cycles whereas many couples with unexplained subfertility will have 5–10 years of reproductive chances ahead, corresponding to 60–120 cycles. Thus, the contribution of these IUI COS cycles on the overall reproductive outcome might be rather limited and should be considered with care, specifically when high multiple pregnancy rates occur.

Only three studies in this IPD analysis included IVF, of which one was relatively small (Hughes et al., 2004), one used IVF elective single embryo transfer (Custers et al., 2011) and one was relatively old (Goverde et al., 2000). As a consequence, no firm conclusions can be drawn regarding the relation between prognosis and treatment outcome after IVF. Nevertheless, these are the only data available on treatment-naïve couples ever randomized between assisted conception and EM (Pandian et al., 2012). Only one relatively old study that compared IVF with EM did not supply data because the data were no longer available (Soliman et al., 1993). The fact that all the data on IVF cycles performed within clinical trials are, in one way or another, of relatively poor quality stresses the need for RCTs studying IVF.

Conclusion

Although we did observe a trend in the prognosis-by-treatment curves towards a relation between the chances of natural conception and the outcome of treatment, we did not find a significant effect of prognosis on treatment outcome. The included studies in themselves are too small to detect any differential capacity of the prognostic models on treatment outcome. The heterogeneity in treatment protocols precluded the use of meta-analysis and the benefits of increased precision from pooling data. Additional data from larger trials are needed to evaluate the existence of a differential effect of prognosis on treatment outcome with greater precision.

Authors' roles

B.W.J.M. is the principal investigator of this study. N.M.v.d.B. and A.J.B. are responsible for the literature search and N.M.v.d..B. is responsible for the overall logistical aspects of this study, drafted the first version of this paper and performed the analysis together with K.O.R., P.B., B.W.J.M., F.v.d.V., and P.G.A.H., S.B., I.M.C., A.J.G., D.S.G., P.S., E.C.H. shared their data and all authors read and approved the final paper.

Funding

This study is financially supported by the Academic Medical Centre and the Vrije Universiteit Medical Centre. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Exclusive licence

N.M.v.d.B. has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors.