Introduction

Throughout history, Iran has been situated at a crossroads of movements of peoples and intermingling of cultures. The rich linguistic heritage of the country reflects this diversity and dynamism. Many languages, from several language families, are represented: Iranic, Turkic, Semitic, Indic, Dravidian, Armenian, and Kartvelian, as well as sign languages. Some of the languages in these families have dozens, or even hundreds, of distinct dialects.Footnote 1 Yet the language situation of the country as a whole is still incompletely documented.

Since the 1950s, there have been a number of important efforts to map out the languages of Iran, but until now no language atlas, or even a comprehensive and detailed country-level language map, has been produced.

This paper opens with a review of important contributions to the mapping of Iran’s languages, along with some recurring limitations and challenges. We then introduce one of the recent projects that seeks to provide a complementary, integrated picture of the language situation: the Atlas of the Languages of Iran (ALI) research programme (http://iranatlas.net).Footnote 2 The body of the article outlines the objectives of the ALI research programme, the architecture of the online atlas, research methodology, and preliminary results that have been generated. The article concludes with a discussion on the contribution of the atlas, and prospects for its ongoing development and enhancement.

History of Efforts

The concept of a language atlas for Iran is nothing new.Footnote 3 Over sixty years ago, in the 1950s, the late Georges Redard at the University of Bern in Switzerland first moved ahead with the idea of working on an Atlas Linguistique de l’Iran. Data were gathered from 43 locations before the doors closed on the project, but these data have never been published.Footnote 4

In the 1970s, the Persian Academy, in collaboration with the Iranian National Geographic Organization, likewise set out on an ambitious documentation project known as Farhangsāz.Footnote 5 This time, more than 16,000 questionnaires and 14,000 recordings were collected.Footnote 6 However, with the change of political landscape at the end of the decade, the project was discontinued and it shared the fate of Redard’s earlier work: with few exceptions,Footnote 7 this wealth of data has never been analyzed or made available to the public.

The current successor to Farhangsāz is a large-scale language atlas programme which has been in operation for about seventeen years, and is carried out by the Iran Cultural Heritage Organization (ICHO).Footnote 8 Some publications documenting the linguistic characteristics of particular regions and varieties have appeared,Footnote 9 and further results in the form of an atlas, which is planned for publication in CD-ROM format,Footnote 10 are eagerly awaited by the academic community and the public.Footnote 11

In addition to these country-wide atlas initiatives, a number of projects have been conducted which offer significant contributions to the mapping of Iran’s languages, although the geographic and thematic scope of each of them is more specific or different from that of an atlas dedicated to the languages of Iran as a whole. Important examples of such atlas projects are: Stilo’s Atlas of the Araxes‒Iran Linguistic Area, which looks at linguistic features in specific locations of language contact and convergence in the north-western quarter of the country;Footnote 12 Labex EFL’s planned mapping of linguistic microvariation in the Eastern Mediterranean–Iran–Caucasus region;Footnote 13 and several linguistic map seriesFootnote 14 and atlas projects initiated for specific regions of Iran.Footnote 15 Key maps which show language distribution for the entire country, albeit as a generalized representation, are those of TAVO,Footnote 16 Izady,Footnote 17 Windfuhr,Footnote 18 and Irancarto.Footnote 19

In short, important language mapping research has taken place, and much more has been planned, but a comprehensive, detailed picture of the language situation in Iran, and a systematic overview of key linguistic features of these languages, has yet to appear in the form of a fully-fledged atlas.

For those projects which aim toward this consequential goal, there have been, and remain, an array of impediments to the development and completion of an atlas of Iran’s languages. These obstacles, which have been discussed more fully elsewhere,Footnote 20 include the sheer diversity of language families and individual language varieties spoken here; incomplete coverage and documentation of these languages, despite a history of documentation extending back more than a century;Footnote 21 issues of funding, logistics and project design; contrasting perspectives on language identity and distribution;Footnote 22 limited dissemination of project results; and limited cooperation among scholars working toward the common goal of a language atlas.Footnote 23 Any atlas project for Iran needs to come to terms with these issues in order to accomplish its objectives.

The ALI Research Programme

In order to address this gap in the literature, the Atlas of the Languages of Iran research programme was initiated in 2009, and first received seed funding in 2014. Today, ALI is an online, open-access resource (http://iranatlas.net), which is currently being developed by an international group of institutional partners and scholars.Footnote 24

Goals and guiding themes

The overall goal of the ALI research programme is to enable work toward a systematic understanding the language situation in Iran.Footnote 25 This initiative, which has the online Atlas at its core, is guided by a set of interrelated themes and questions:

Linguistic typology: What are important linguistic features of Iran’s languages and dialects, and how are they distributed geographically?

Language distribution: Where are these language varieties spoken, and how does this compare to the distribution of linguistic features?

Language classification: How do scholars and speakers classify these language varieties, and how can scholarly classifications be improved?

Language documentation: A record of the linguistic situation in Iran and a repository of linguistic data before the disappearance of much—perhaps most—of the linguistic diversity with the extension of standard, Tehran-type Persian as a mother tongue across the country.

The ALI project team, research process and atlas architecture have been brought together and crafted in direct response to the challenges which face a project of this type, as outlined in the previous section (“History of Efforts”).

Research team

The ALI research group includes scholars from twelve countries, with Iran represented foremost among them.Footnote 26 The diverse constitution of the team ensures that a wide variety of opinions and expertise are represented and communicated to the Atlas’ varied audiences, and volunteer contributions made by these researchers have enabled the project to move forward steadily.

Data platform, structure, and publication

ALI is published as an open-access, online resource and is being built by programmers at the Geomatics and Cartographic Research Centre (GCRC) using the open-source Nunaliit Atlas Framework (http://nunaliit.org),Footnote 27 which comes with a free and ready-made atlas template. In contrast to most commonly-used GIS packages such as ArcGIS or QGIS, which import static datasets into the program and focus on optimal visual representations, Nunaliit uses a “related-document” structure which is designed to handle complex relations among evolving data.Footnote 28 Inside a Nunaliit atlas, each piece of data is stored as a document with a flexible set of attributes, and each of these documents can be related to any other document in the atlas. This necessitates more initial set-up work in building an atlas, but once an atlas is operational, relations between data are easy to build, navigate, and process. For example, in a language atlas, an audio or video recording can easily be uploaded and associated with any other document (i.e. piece of data) in the atlas, such as:

the particular settlement where it was collected, along with demographic information for that place;

the category of linguistic data it shows: a certain word, grammatical construction, etc.;

the language variety that it represents, and in turn, language classifications;

clear acknowledgment of data sources: the speaker, and the person who contributed it to the atlas; or, in the case of published data, a reference to the website or book that it comes from.

All of these data types can be accessed directly through country- and province-level language distribution maps as well as other atlas modules including linguistic structure maps, language classification diagrams, and the bibliography.

The intricacy of the language situation in Iran necessitates a purposeful approach to data structure, and all of the country’s some 60,000 cities and villages are placed in ALI as potential sites for data collection. Contrasting opinions on language classification add to this complexity. However, as will be shown below (“Language classification”), Nunaliit’s related-document structure helps to define the geometry of relationships among language varieties and distinguish different kinds of relationships between them. Its interactive model-driven approach enables it to take into consideration differing scholarly opinions about classification in the same diagram, and to produce different maps on the basis of these different perspectives.

Another key feature of a Nunaliit-designed atlas is its dynamic online platform. Nunaliit enables direct remote contributions by researchers, and by atlas users generally, from anywhere that has an internet connection, and collection and subsequent upload of data from locations without such a connection. To help ensure consistency and reliability, a system for moderation and double-checking of data is an integral part of the data contribution process. The simple fact that the atlas is online means that each portion—and even each piece of data—can be published as soon as it becomes available; there is no long wait for the release of a complete print version.

The open-access format of the Atlas, simultaneously published in Persian, English, and French, enables a wider, more engaged audience than a print version. As with other state-of-the-art atlases that use open-source code,Footnote 29 the programming work that goes into the production of each Nunaliit atlas is made freely available to other scholars on Github.Footnote 30

Considering all of these points, the basic choice of an online forum for ALI—and use of the Nunaliit Framework in particular—helps to address many of the challenges mentioned above (“History of Efforts”): an extremely complex language situation; contrasting perspectives on language classification and distribution; logistical considerations, including project funding; a forum for cooperation among scholars working toward the common goals of a language atlas; and dissemination of project results.

Key Atlas activities

The four main areas of current activity and production in ALI, proceeding from the programme objectives outlined above (“Goals and guiding themes”), are:

linguistic structure maps;

language distribution maps;

language classification; and

compilation of atlas resources.

This latter activity includes collection of oral texts as part of the fieldwork process, as well as the compilation of a reference list dedicated to materials relevant to mapping and documentation of the languages of Iran.Footnote 31 This reference list is valuable because it points users to each piece of published data that is cited in the Atlas, and as it becomes more complete, it will serve as a comprehensive bibliography of all works related to the languages of Iran.

All of the four activities are essential to the development of a fully-fledged language atlas, and deeply integrated with one another through a cyclical research process in which each activity informs the others (for further discussion, see “Conclusion”): while linguistic structure maps may be viewed by linguists as central to a language atlas, and language distribution maps are often of greatest interest to a popular audience, language classification and compilation of atlas resources are seminal, ongoing activities that frame mapping activities and enable progress towards the production of maps. In the following sections, we will treat language classification, language distribution, and linguistic structure mapping in detail, and in this order, which reflects the methodological foundation and research process of the work.

Language Classification

In many language atlases, language classification is incidental to the research process. For Iran, however, careful treatment of this issue is essential to building a resource that handles linguistic data in a systematic way and is at the same time satisfactory for the diverse audiences of the Atlas.Footnote 32 A comprehensive and well-grounded classification provides a context for identification of any language variety, review of scholarly consensus and differences of opinion, corroboration with perspectives of speakers and, ultimately, an overarching organizational structure for linguistic data in the Atlas. ALI’s classificatory activities and features have been treated more fully elsewhere;Footnote 33 basic elements and highlights are reviewed here.

There are two models through which language classification is organized in ALI: a traditional classification organized as a two-dimensional tree structure,Footnote 34 and a multi-dimensional web model that allows for additional relational and representational possibilities.Footnote 35

In the two-dimensional classification, we bring together all language families, languages and dialects of Iran; and, in order to be topically complete, all languages of the Iranic (Iranian) family which are spoken outside of Iran are also included. This working classification has been developed through consultation of the literatureFootnote 36 and, as explained on the Atlas page dedicated to this two-dimensional model, the language families and subgroups of the tree have been reviewed by experts in the field.Footnote 37 A total of over 500 language varieties are inventoried here so far, of which about 400 belong to the Iranic family. This count is constantly expanding as ALI researchers encounter additional varieties in the literature as well as in the course of language distribution fieldwork.

One of the key features of this classification, as presented in the Atlas, is the backgrounding of assessments of a given variety as a language versus a dialect.Footnote 38 Many classifications,Footnote 39 as well as other types of linguistic and popular discourse, treat these two categories—“language” and “dialect”—as discrete and objectively identifiable. However, in the context of Iran, differences in the factors that people rely on for their assessments lead to greatly differing lists of languages for the country. Whereas official administrative materials usually specify between four and seven languages,Footnote 40 and popular sources have similar lists,Footnote 41 scholars often cite dozens,Footnote 42 and one source—Ethnologue—lists 80 distinct languages.Footnote 43 Counts given by speakers of the country’s many languages are between the two extremes, but mother-tongue speakers of Tehran-type Persian consistently provide smaller lists than speakers of minority language varieties.Footnote 44 In short, there is no single, definitive list of Iran’s languages that will adequately address the diverse audiences of the Atlas, even though all of them might expect one. But assessments of “language” vs. “dialect” do not contribute to the main purposes of the Atlas (see “Goals and guiding themes” above), and because of this we have chosen instead to focus on assembling an ever-expanding list of language varieties, and exploring the ways that these varieties fit together into a single coherent picture.Footnote 45

Because of its conceptual simplicity, informed by the comparative method,Footnote 46 the two-dimensional tree representation is useful as an indexing tool, and perhaps because of this, in practice it remains the dominant model in language classification today.Footnote 47 Still, even when distinctions of language and dialect are backgrounded, it is not ideally suited for the purposes of ALI, since contrasting viewpoints, arguments, and justifications for a given classification decision have to be relegated to footnotes and accompanying discussion.

Despite its pervasiveness in historical linguistics, the tree model of classification has come under persistent criticismFootnote 48 since shortly after its elaboration by Schleicher in the mid-1800s.Footnote 49 Among other issues, it overlooks the contribution of areal phenomena such as transitional structures and effects of contact, whatever the genealogical (i.e. genetic) relationFootnote 50 between language varieties. A “wave” model of language relationship, proposed in response to this gap,Footnote 51 has increasingly gained traction among scholars; and sophisticated expressions of the wave model, informed by the comparative method, have been developed recently.Footnote 52

For issues of classification, the ALI research team seeks to handle fundamental constraints of existing models, treat the complexity of the language situation in a reasoned and systematic way, and to operationalize new insights in the design of the Atlas. To this end, the authors of this article, assisted by geographic data technicians and programmers at the GCRC, have developed a multi-dimensional web model of classification for the languages of Iran (Figures 1 and 2).Footnote 53 This model contains all of the same content as the two-dimensional tree model, but allows for various types of relations to be expressed within the same diagram. The labelled diagram in Figure 2, while visually overwhelming, is a fitting representation of the complex language situation.

Figure 1. The Languages of Iran as Represented in a Multi-Dimensional Language Classification Web.

Figure 2. The Languages of Iran in a Multi-Dimensional Language Classification Web, with Language Variety Labels. Note: this figure shows static output from the interactive module.

Genealogical relations, as established by the comparative method, form a central organizing principle for the representation (Figure 3). Structural similarity through language contact is another way in which varieties can be connected to one another (Figure 4), as is relationship through ethnic identification (Figure 5). Explanations and examples of each of these types of relations are more fully detailed in the studies dedicated to this topic.Footnote 54

Figure 3. Sample Multi-Dimensional Representation of Genealogical Relations.

Figure 4. Sample Multi-Dimensional Representation of Structural Similarity through Language Contact.

Figure 5. Sample Multi-Dimensional Representation of Relationship through Ethnic Identification.

While the multi-dimensional model for language classification has wider implications for historical linguistics, it also provides a reasoned and systematic way of making explicit how the complexities of the language situation are treated in the Atlas. Importantly, the ALI project is currently exploring the way in which presuppositions and perspectives from different audiences, when applied systematically, define the maps that are produced.Footnote 55 Ongoing refinement of language classifications through field research and analysis of linguistic data, discussed in the following sections, sets in motion a dialogical research process for the Atlas.

Language Distribution and Local Place Names

While linguistic structure maps—described in the following section—are an ultimate goal for the output of the Atlas, there is a significant amount of preparatory work that goes on for each province before linguistic data collection can take place. Since it is not practical (and probably not even possible) to gather systematic linguistic data from each language community in each of Iran’s some 60,000 cities and villages, even with an extended time frame, the research team needs to select research sites judiciously and economically. This, in turn, requires familiarity with the nature and distribution of all of the language varieties that are spoken in each province.

In a series of recent papers, we provide detailed case studies of the language distribution research process for three provinces: Kordestan, Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari, and Ilam.Footnote 56 We are committed to establishing a streamlined, replicable research process for the study of language distribution, but the exact implementation varies from one province to another. It depends on the availability, background, and expertise of the scholars who will carry out this research and, of course, fieldwork conditions on the ground. While language distribution profiles and maps for some provinces have been completed after several months of intensive work, other provinces have taken more than two years to realize.

As mentioned in the paragraphs on “Data platform, structure and publication” above, substantial work goes into the preparation and structuring of the language distribution maps, because of the complexity of the data. A first step for each province is the compilation of a bibliography of all resources pertaining to the distribution of languages of that province, and all resources that contain linguistic data from those languages. From these materials, we are able to establish an initial list of all language varieties that we expect to encounter. With the help of linguists who have worked on the languages of the region, we organize the varieties into an initial working classification—an initial hypothesis that is scrutinized and tested in the subsequent fieldwork.

We then bring together geographic dataFootnote 57 and demographic dataFootnote 58 which the government of Iran makes publicly available. These data are imported and associated with a background map for each province, specially designed to orient the user and foreground language-related data (Figure 6). The background map, with all associated geographic and demographic data, is then ready to be populated by language distribution data gathered through fieldwork.

Figure 6. Sample Background Map: Hormozgan Province.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.hormozgan

Each province is managed by at least one lead researcher, primarily responsible for that area, who directs language distribution fieldwork and carries it out either in conjunction with a team of colleagues (whether senior scholars or students), or independently. For every city or village in each province, the researchers investigate two general topics: language distribution, and local place names.

First, as the major issue, language distribution: (a) What languages are spoken in this settlement as a mother tongue?; (b) Which sub-varieties of these languages are found here?; and (c) What is the estimated proportion of people who speak each variety as a mother tongue?

Members of the research team start out with a solid, fundamental understanding of the language situation in the province they are studying. However, because of the settlement-level scale of the research, in each case they have made important discoveries for themselves regarding the diversity and regional distribution of language varieties. Simply by asking these questions in relation to each settlement, researchers frequently encounter language varieties that have not been reported in the literature; and the local context of their research brings to light language communities’ own perspectives on how their language fits into a more general taxonomy of languages in the country. Both of these elements feed into the elaboration and refinement of ALI’s comprehensive working classification (see “Language Classification” above).

Results of the language distribution research are indicated in each relevant place document, along with the name of the researcher who has contributed their assessment (Figure 7). This stage of the research process, described in detail elsewhere,Footnote 59 is clearly not a census of all individuals, nor would it be feasible to aim for this. Rather, these investigations yield estimates for each place and are clearly indicated as such. Linguists and other Atlas users who have more detailed local knowledge about language distribution in particular settlements are able to propose corrections and updates directly through the moderated Atlas interface (see “Data platform, structure and publication” above).

Figure 7. Sample Language Distribution Document: Qorveh.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.kordestan

At the same time as investigating language distribution, researchers ask about local names for each settlement, as pronounced in the languages spoken there. Often, the local name is different—whether partially or completely—from the official Persian name. A few examples from Bushehr Province are as follows:Footnote 60

Local pronunciations are an important means of highlighting the diversity of the language situation on the ground, and serve as a way of connecting with each community featured in the Atlas. Phonemic transcriptionsFootnote 61 are supplied for each place, and where the research team has prepared them, IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) transcriptions and/or recordings are also made available.

Now three years into the ground-laying process of language distribution research, interactive point-based language distribution maps in ALI have been completed for five provinces of Iran, in the following order: Hormozgan, Kordestan, Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari, Bushehr, and Ilam (Figures 8–12).

Figure 8. Language Distribution in Hormozgan Province.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.hormozgan

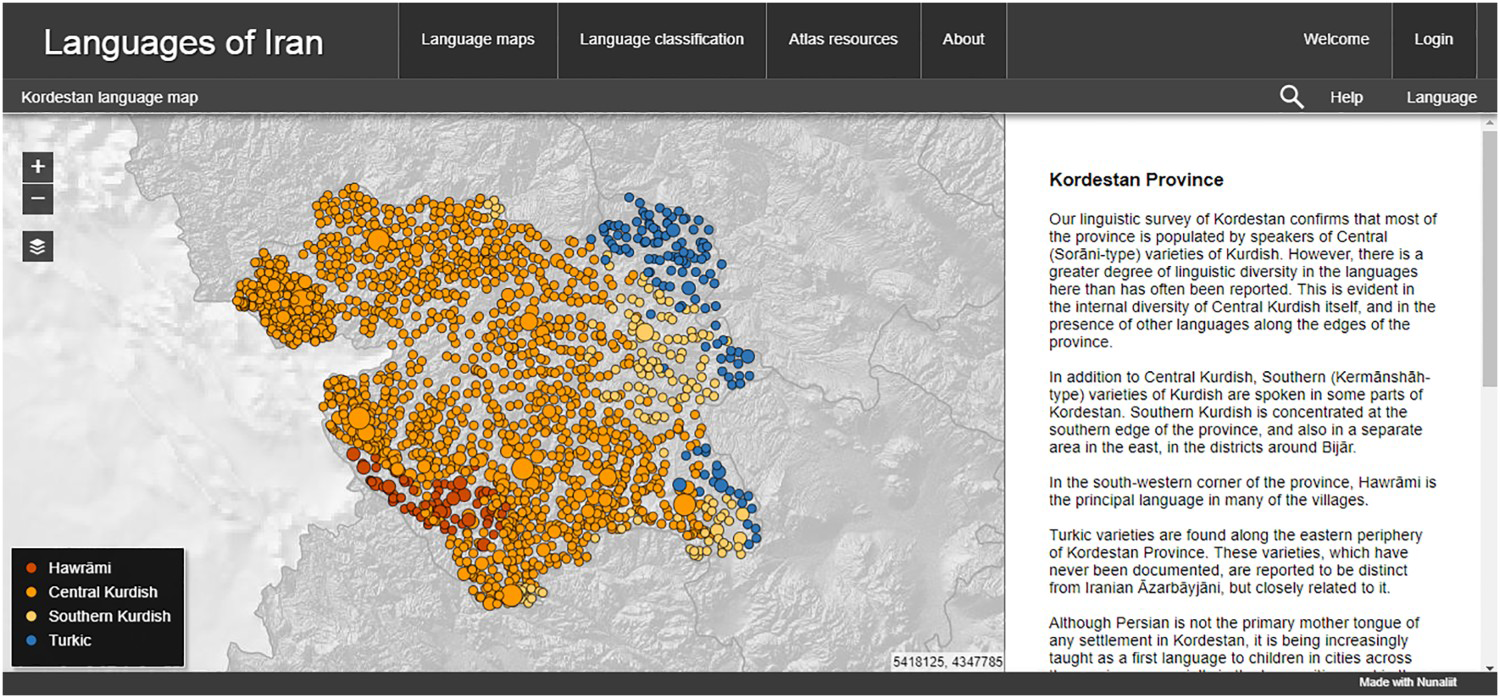

Figure 9. Language Distribution in Kordestan Province.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.kordestan

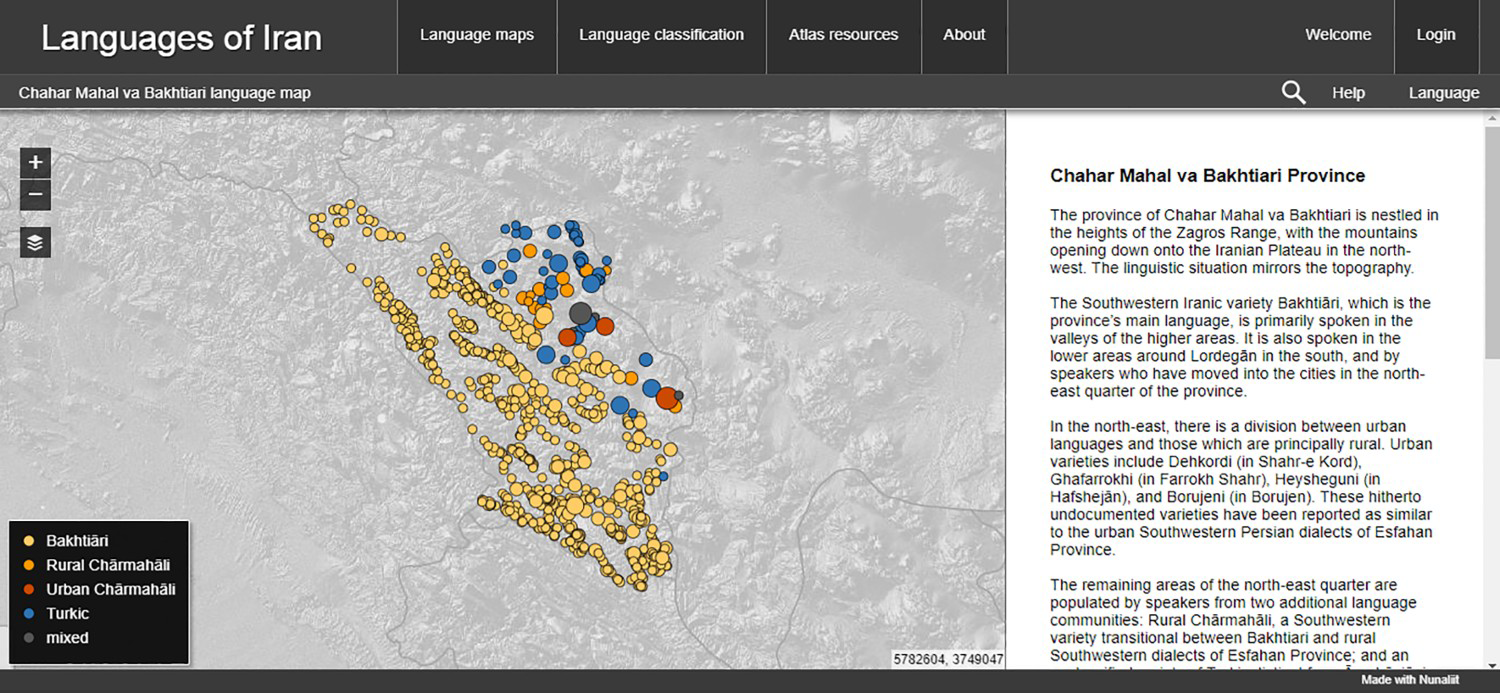

Figure 10. Language Distribution in Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.chahar_mahal_va_bakhtiari)

Figure 11. Language Distribution in Bushehr Province.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.bushehr

Figure 12. Language Distribution in Ilam Province.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.ilam

We are also developing the capability of constructing country-level language distribution maps for any individual variety or group of varieties selected by Atlas users (Figure 13).Footnote 62

Figure 13. Sample Language Distribution Map for Individual Varieties: Arabic in Bushehr and Hormozgan.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.single_language

Finally, in response to requests from other scholars, we have generated traditional static polygon maps as an alternative representation of language distribution (Figure 14).Footnote 63 These three types of maps constitute the first series of fine-grained language distribution maps published for any part of Iran, and together they are contributing to a more coherent and detailed picture of language distribution for the country as a whole.

Figure 14. Static Polygon Representation of Language Distribution in Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/language-distribution.chahar_mahal_va_bakhtiari_static

Importantly, for the purposes of the ALI research programme, the results of language distribution research also provide a basis for representative and economical selection of research sites for collection of linguistic data. This next stage of the research is described in the following section.

Collection and Mapping of Linguistic Data

The mapping of linguistic data—words, phonological features, grammatical features—is at the heart of any fully-fledged language atlas. All of the elements described so far, and especially research on language classification and language distribution, are necessary precursors to the collection, analysis, and mapping of linguistic data, since these data are principally meaningful in relation to their wider comparative linguistic and social context.

The language distribution maps developed for each province provide an accessible point of reference for identifying evenly distributed sites for collection of linguistic data. Generally, for each language varietyFootnote 64 identified in the language distribution phase, the Atlas aims to collect linguistic data from one representative site in each shahrestān (provincial sub-district) where that variety is found. In addition, since language contact phenomena are an important aspect of the language situation, data collection sites are selected at the edge of language areas, in dialectically transitional areas, and in multi-lingual cities and villages.

For larger, more linguistically diverse provinces like Hormozgan (Figure 8), these parameters necessitate data collection from well over 50 research sites. Even for a small and relatively less diverse province such as Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari, we are aiming to collect data from thirty-five locations. At present, the research team for that province, led by Mortaza Taheri-Ardali, has collected ALI pilot questionnaire data from thirty of these locations (Figure 15).Footnote 65 As Figure 15 shows, the selected linguistic data collection sites are clustered in districts with a higher level of linguistic diversity.

Figure 15. Locations for Collection of Linguistic Data in Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province.

Source: http://iranatlas.net/module/linguistic-data.cb-research-sites

Other sites where the Atlas team has already carried the pilot questionnaire out are located in Hormozgan (10 locations), Ilam (5), Kermanshah (1), Esfahan (1), Markazi (1), Boyerahmad va Kohgiluyeh (1) and Sistan va Baluchistan (1), bringing the total to 50 locations so far.

Two types of data are collected in each location: oral texts, including high-quality audio as well as video format whenever possible; and a uniform dataset across all research sites based on responses to the ALI linguistic data questionnaire.

The ALI linguistic data questionnaire

Collection and analysis of oral texts is essential in understanding natural patterns of discourse and language use; in contrast, design and administration of a linguistic data questionnaire is a systematic and efficient means of gathering focused data that can answer very basic—but hitherto unresolved—questions about the language situation in Iran, as well as the typological diversity and geographic distribution of linguistic structures.

The ALI questionnaire is designed specifically for the languages of Iran, with attention to “classic” features and isoglosses identified and applied by scholars in the field of Iranian linguistics, but going beyond these as well. Along with recurrent themes in the literature such as those found in the Compendium Linguarum Iranicarum,Footnote 66 the features treated in Stilo’s Araxes-Iran atlas projectFootnote 67 and the dialectological questionnaire published by the Persian Academy (Farhangestān)Footnote 68 have been foundational in defining the content of the ALI questionnaire. In order to ensure typological breadth and applicability to other language families in Iran, the questionnaire has been further developed in consultation with, among others, Comrie and Smith’s (Reference Comrie and Smith1977) typological questionnaire, still a standard in the field today;Footnote 69 features in the World Atlas of Language Structures (WALS);Footnote 70 and the Swadesh and Leipzig-Jakarta wordlists.Footnote 71 Chan’s questionnaire on numeral systemsFootnote 72 has also been incorporated.

The main elements of the questionnaire, for which parallel Persian and English versions are available, are: sociolinguistic context for each research site; lexicon; phonology; and morphosyntax (grammar).Footnote 73 Over a two-year period, from mid-2015 to mid-2017, the pilot version of this questionnaire was carried out in the fifty locations mentioned earlier in this section.

In the summer of 2017, the questionnaire was revised with the in-depth input of experts as part of a workshop at Bamberg University.Footnote 74 Major improvements to the questionnaire, according to the various topics covered, were as follows:

Sociolinguistic context: inclusion of questions that help provide a more detailed picture of respondents’ linguistic background and use, since these factors have a major impact on the linguistic structures that are elicited.

Lexicon: augmentation of the lexicon section, which was straightforward to administer, and which produced clear and meaningful results, from 80 to 130 words; additional elicitation supports, such as explanations and pictures, for semantically problematic items.

Phonology: removal of the dedicated phonology section, including the comprehensive phonemic inventory, which required a long segment of interview time, a high level of phonological expertise, and the ability to design and conduct ad hoc analyses and proofs; redistribution of the more basic and important synchronic as well as historical phonology-related questions into the lexicon and morphosyntax sections.

Morphosyntax: complete redesign of the morphosyntax section to enable researchers without expertise in this domain, or in a given language family, to administer the questions more easily; provision of supplementary context for discourse-dependent topics such as definiteness and morphosyntactic alignment; elicitation and tagging of data according to grammatical functionFootnote 75 rather than a closed set of expected structural possibilities.

In addition, the questionnaire as a whole was repurposed to take into account considerations of design and content related to Turkic, Semitic, and the other language families found in Iran.

Following on testing of this refined, definitive version of the questionnaire,Footnote 76 it has been recently released for use in the ALI project.Footnote 77

Processing and mapping of linguistic data

Whenever field researchers complete linguistic data collection using the ALI questionnaire, they transcribe all the data according to the project transcription conventionsFootnote 78 and send it to the province team manager for an initial check. Once outstanding questions have been defined and addressed, the manager then brings together and organizes, in an Excel file, data from all research sites in that particular province. The Atlas editors carry out a further check of the data and, together with all colleagues who have worked on the data, identify regularities in the linguistic patterning and geographic distribution of individual structures.

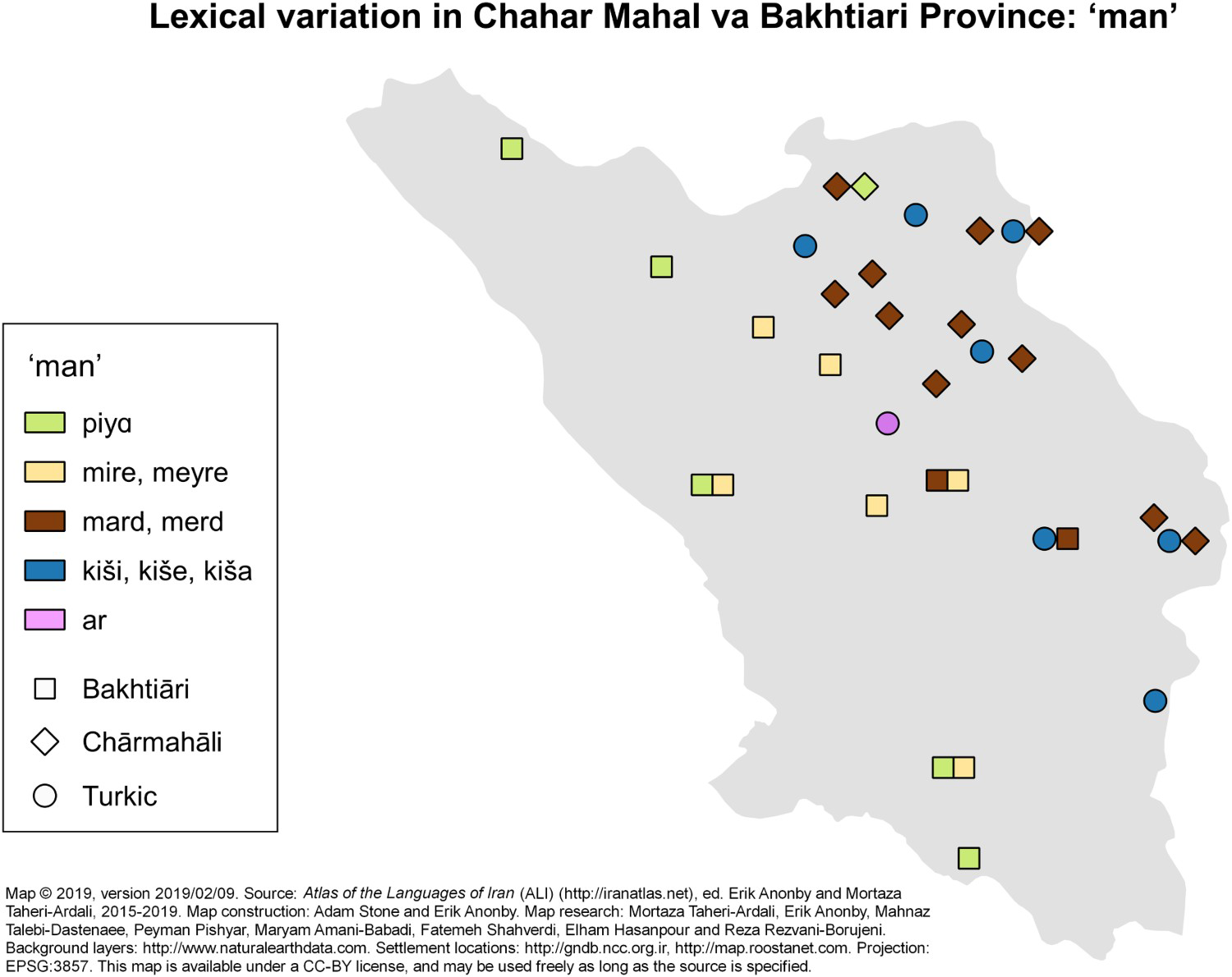

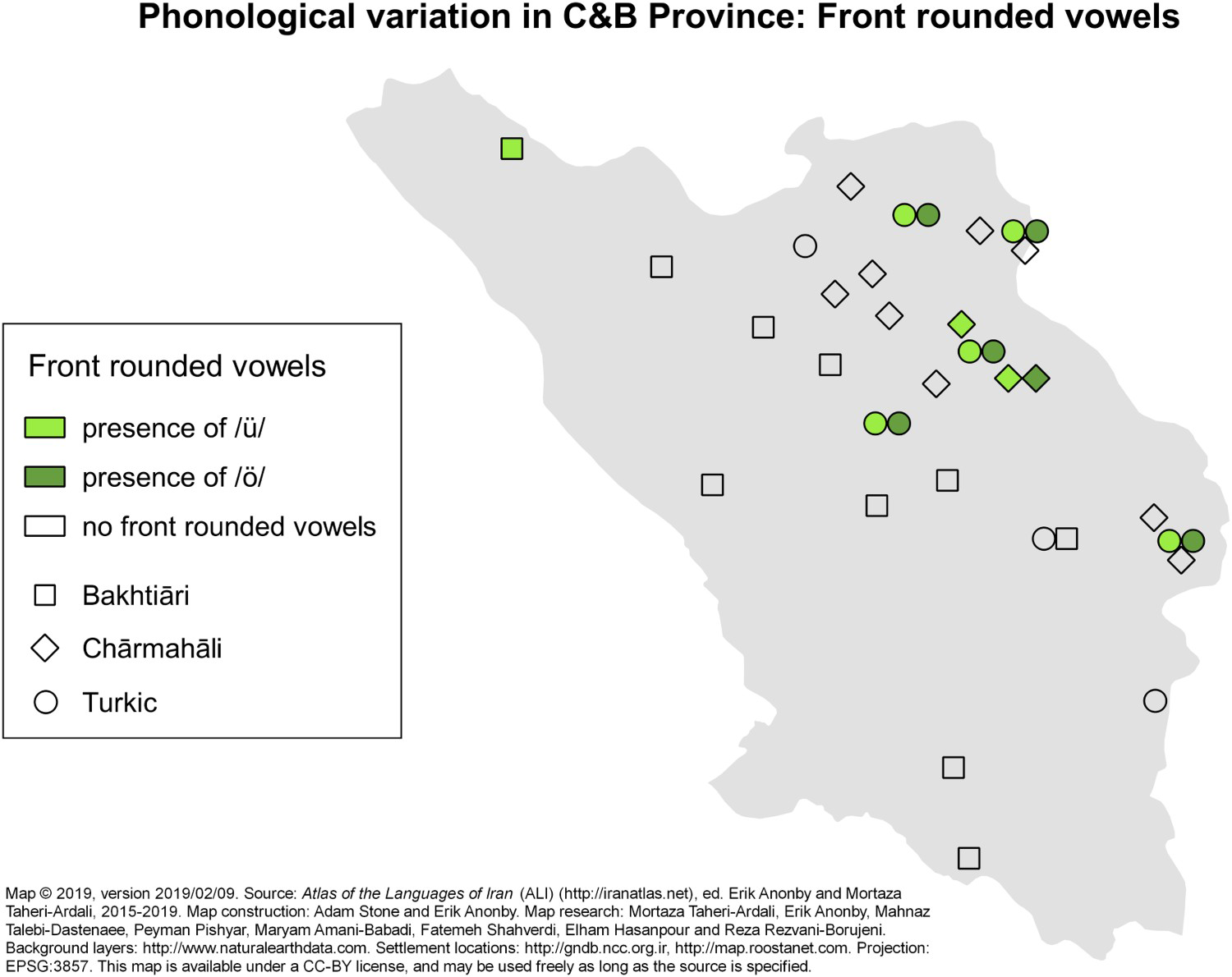

Results of linguistic data collection are currently being analyzed and released as papersFootnote 79 and as maps on the Atlas website. The region for which data collection, processing, and publication is most advanced is that of Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province, where comparative analysis has been carried out (Figure 16 shows a sample of the data) and a series of static lexical and phonological maps have been produced (Figures 17–19). While these maps reveal meaningful patterns on their own, they are important as a foretaste of the contributions that will be made by maps in other domains—notably morphosyntax—and in other provinces of Iran. Currently, as the data are being analyzed, it is giving insight into planning for the kind of programmatic structuring that will be necessary to turn the Atlas’ experimental dynamic language maps into fully developed maps—maps in which the form- and function-tagged linguistic data are fully integrated with the existing architecture of the Atlas and made accessible to users for easy output of the data in tabular format and creation of their own interactive maps in the Atlas.

Figure 16. Sample Lexical Data Sets from Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province.

Figure 17. Sample Lexical Data Map: ‘Leaf’ in the Languages of Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province.

Figure 18. Sample Lexical Data Map: “Man” in the Languages of Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province.

Figure 19. Sample Phonological Data Map: Front Rounded Vowels in the Languages of Chahar Mahal va Bakhtiari Province.

Conclusion

This article provides a first global description of the Atlas of the Languages of Iran (ALI) research programme. It begins with an account of efforts to map the languages of Iran, from the 1950s until today, and a review of challenges that have faced this enterprise.

The ALI programme, designed to address these challenges, was initiated in 2009 and has moved forward steadily since seed funding was obtained in 2014. The overarching purpose of this research programme is to enable work toward a systematic understanding the language situation in Iran. This work, which has an online Atlas at its core, revolves around the exploration of the typology, distribution, and classification of the languages of Iran. Further, Atlas activities are conceived to contribute to the documentation of the language situation in the face of the decline and, in many cases, disappearance of these languages as standard, Tehran-type Persian is increasingly adopted as a mother tongue in areas across the country.

The Atlas at the centre of this project is built using the Nunaliit Atlas Framework. Nunaliit’s related-document approach and a range of rendering and input options enable a research process and product capable of handling complexities of the language situation in Iran and reaching the diverse audiences of the Atlas in an accessible way. Key elements of present Atlas production include a multi-dimensional working classification of all language varieties in the country; language distribution maps; and linguistic structure maps generated through the collection and analysis of systematic questionnaire data. While all of these elements are important in their own right, each one contributes to the understanding and development of the others. Ongoing comparison of linguistic structure maps with language classifications, and with language distribution maps, ensures that the picture that emerges is grounded in the actual forms that speakers use. This multi-faceted perspective is critical, since linguistic data are often ambivalent with respect to language classification, and rarely show neat correspondences to perceived geographic boundaries between language varieties. Conversely, a clearly elaborated language classification and a detailed picture of language distribution provide a comparative linguistic, and social, context for these data.

Areas of current activity include the study of language distribution for remaining provinces of Iran; carrying out of the revised linguistic data questionnaire in provinces where language distribution research has been completed; and construction of an accessible portal where linguistic data are made available for download and display on user-constructed maps. Thanks to the open-source technology and the dedication of the research team, the project is sustainable in a context of modest funding. Building on the foundation of more than a century of documentation, and alongside complementary initiatives, the Atlas of the Languages of Iran is contributing to a clearer picture of the diverse language situation in Iran.