Abstract

This paper aims to answer the pertinent question: What are the implications of ideology on school buildings and the culturally pluralistic context of Gazimağusa in Northern Cyprus? It traces the social and communication qualities of architecture to restructure the architectural identity of schools and the cultural patterns of this city during the British Period (1878–1960). The colonialists relied on education as an ideological tool for perceiving social and economic stability through training a new, educated middle class to replace the existing traditional authorities: Ottoman leaders and Church structures. Their failure to recognize the diverse cultural layers of the context led to unsustainable outcomes. An interpretative case research approach that involved descriptive and historical techniques was utilized to investigate this situation. Ideology had two separate but related consequences in the context chosen at both urban and architectural scales. Resulting in a cultural shift from intrinsic to extrinsic living that contradicts previous cultural alignments of the place. The urban syntax for communal life shifted to exclusivity, and cultural coexistence was divided between Turkish and Greek Cypriots on the one side; on the other, schools copied a globalized character of transformation. Based on contextual perceptions, the study advocates for a creative cultural mix of local and global concepts. The island went through modernization, hosting the two communities under British Colonial Rule who were both struggling with the colonizers on one hand and experiencing ethnic and political clashes on the other; they formed the conditions for a wide variety of school buildings. Within this context, the paper highlights school buildings as an ideological space, symbol, and tool of nationalism and colonization/decolonization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rich cultural diversity present in all three of Cyprus’ major historic cities—Lefkosa, Gazimağusa, and Girne—is one of the distinctive values threatened by the island’s division. Although Gazimağusa was not in charge of administration, as a port city, it rose to prominence as a hub for trade and tourism under British Rule (Newman, 1953, pp. 200–210). Since 1974, this significant city has been divided, with the Greek Cypriots now residing on the south side and the Turkish Cypriots on the north side. The island’s cultural layers have been shaped over time by marks from different civilizations, including Arab, Roman, Byzantine, Lusignan, Venetian, Ottoman, British, and others with roots in Cyprus. Greek and Turkish Cypriots make up the two largest communities in that cultural trajectory as an outcome of nationalistic ideologies, which led to spatial differentiation after the British Period in Cyprus (Foka, 2020). Because it is a prime example of a medieval city with a cosmopolitan, culturally diverse character, Gazimağusa is brought into the spotlight. The Greeks gave the city the name Ammochostos, which translates to “buried in the sand” and refers to the silt sand from the Pedieos River. While the Turkish version of the name was Mağusa (Gazimağusa), where Gazi means veteran, the Latins changed the name to Famagusta around 1200 AD (Stillwell et al., 1976). Based on the ethnographic documents used, this paper chooses to use either Famagusta or Gazimağusa interchangeably. This is part of the cultural changes that still confront this city today.

The city of Gazimağusa has endured centuries of cultural diversity while maintaining its quality and integrity (Carr, 1994, p. 250). Its northern border is formed by the ancient City of Salamis’ ruins, which include both Greek and Roman artifacts. Kato Deryneia, which shares boundaries with Varosha, is located south of the city (Maras). Varosha had a wealth of modern architecture, especially in the many hotel buildings constructed in its surroundings during the British era, along with tourism developments along the Mediterranean Sea. Due to the effects of the island’s major division in 1974, it is currently struggling to recover from urban decay and desolation (Tofallis, 2002, pp. 76–104). The Mediterranean Sea separates Famagusta from North Africa and to the east of the Middle East. While Lefkosa is to the West (Nicosia, the administrative city of Northern Cyprus). The fact that this city had previously been ruled by several empires and civilizations, including the Byzantines, Venetians, and Ottomans, shows that it has a long history of adaptability and resilience in the face of change. The three significant civilizations in history are the Lusignan (1192–1489), Venetian (1489–1571), and Ottoman (1571–1878). It also has a distinctive identity because of the presence of the “Walls of Famagusta,” medieval fortifications that surround a historic city.

The British colonialists also displayed ideological roots in Hegelian and Marxist philosophies while attempting to introduce the Cypriots to the secular culture that was prevalent in Europe around the 19th century. Yet Cypriots’ encounter with the Europeans brought about a change in lifestyle from pious to secularized, prosperity in the economy, and an educated class for a functional bureaucratic system. The nuclear family system replaced the extended family system that the Ottomans left behind (Luke, 1989). Their concepts are condensed into context because there is a fundamental force that governs every age and controls and influences everything that happens. In keeping with previous events, the destruction of World War I facilitated the British annexation of Cyprus in 1914. The tax burden and island-wide economic downturn caused by the Ottoman Administration gave rise to this scenario. Cyprus was made a Crown Colony in 1925, but British rule ended in 1960; the year of independence marked the transition of powers to the Republic of Cyprus. Famagusta, once regarded as one of Cyprus’s major cities and a strategic harbor city, had a lasting impact on British rule. They celebrated the spirit of the era as a global ideological wave and a global cultural movement, impressing the setting with both the positive and negative effects of imperialism. Additionally, they used educational institutions as tools to spread their beliefs and ideals. In contrast to Dominions (such as Australia, South Africa, and others) and Protectorates (such as Nigeria, Sierra Leone, and others), where the English language was made mandatory in schools like primary and secondary (Ajepe and Ademowo, 2016). The paper adds to the discourse about the relationship between ideology and architecture, and how architecture is understood in context.

Main body

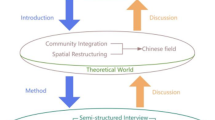

This theoretical section examines how ideology, architecture, and cultural plurality are related to the narrowing of Gazimağusa in Cyprus, now in Northern Cyprus, as a result of the island’s 1974 division into two parts.

Ideology and architecture

Ideology presupposes complex, varied viewpoints in the fields of politics, culture, and literature. It refers to an organized system of concepts, meanings, values, expressions, beliefs, sociopolitical and visual representations, and activities that define the operating principles of social institutions (Terry, 1991, pp. 4–23). Marxists and non-Marxists both have separate advocates who support the idea of ideology. Smelser and Baltes (2001) have explained which of the three interests in the latter group aligns with the objectives of this study. It has been described as an undercover mapping tool of political and cultural concepts and symbols that hold crucial resources for the assimilation and restructuring of sociopolitical life. From this definition, two ideological presumptions have been drawn. The first is concerned with the active or passive provision of plans and initiatives for determining public policy. The second postulate is that social transformation involves combining political alignment and social change. The colonizer and the colonized provide evidence for the same model’s inclusion of power struggles between social classes in society (Barthes, 2009). This communication pattern can also be built using what Althusser (1970) called an ideological state apparatus. The apparatus consists of organizations galvanized by the state to spread its values to people in society to maintain order, such as educational institutions, religious organizations, family institutions, media outlets, and law firms (Malinowski, 1960).

Moreover, in Cyprus, the British Administration incorporated socioeconomic aspirations into education, which Singh and Rex (2003) identified as a tactic to manipulate the locals’ psyches to achieve colonial goals and to create an exclusive class of individuals who would pursue those goals. They went a step further and instituted a representative system of government with an unbalanced power-sharing quota between the Christian and Muslim communities on a culturally diverse island like Cyprus. The lack of cultural validity and inclusivity hinders the freedom and equality proclaimed in the new leadership structure between the Ottoman elites and their subjects, the clergy and the laity, and the peasants and urban elites. Traditional systems of authority (Ottoman elites and Church authorities) were replaced with secular reforms as part of the ideological agenda (Byrant, 2004; Holland and Markides, 2006; Safty, 2011). The politically charged irony of the new structures quickly increased the turn toward cultural differences among the populace, despite the power the educated middle class had gained (Hook, 2015). Local communities began to think of themselves as being kept out of the corridors of power because they were unenlightened, and such sensibilities resulted in a conflict of interests (Pollis, 1998).

A new sense of “identity of equal selves” took the place of the identity of the native Cypriots. Future assimilation was anticipated, which fueled nationalistic tendencies. Due to the emergence of economic subordination as a result of the educated and middle classes’ potential involvement in business, social class differences between the educated class and rural farmers increased (Bozkurt and Trimikliniotis, 2014). Education became essential for a fulfilling life, social mobility, finding work, and maintaining ethnic identities (Argyrou, 1996). The operation of ethnic-based education and secularization kept elementary, secondary, and vocational school buildings as the guardians of particular ideologies (Pollis, 1998; Byrant, 2004; Hook, 2015). Ideology typically belongs to the natural and applied schools of thought. Modern and postmodern architects use symbolism to convey ideology and create cultural systems that shape social and cultural identity. Ideology and architectural theory and their practices are now in alignment, contributing to the transformation of design through time and technology. The need to preserve imperial ideology is evident in the architecture of different British Empire colonies (Thomas, 2015). Among the architectural typologies used to represent their ideas were school buildings, governmental structures like courts, post offices, and other public buildings.

The discipline of architecture serves as both an institution and a social platform that is undergoing change (Agrest and Gandelsonas, 1973). Communication and the changing attributes of this phenomenon, referred to as “social formation” by Ergut (1999), can evoke diverse perceptions. Buildings are considered social objects that represent ideas, values, and beliefs, connecting architectural objects to social practices through symbolic and imaginary construction. Ideology and architecture combine to inspire modern and postmodern works (Šuvaković, 2014, pp. 2–12). These theories explain how architecture interacts with society while hiding its impact on nationalism through technocrat-esthetic and technocrat-artistic methods (Pantelić, 1997). Although modern and post-modern architecture may not be directly tied to ideological philosophy, it still values and appreciates it as both an esthetic and a method of conceptualization. It serves as a symbolic representation of the work produced (Shusterman, 2009). Here, imperialism, nationalism, and architecture are combined to create a national order with tangible and symbolic cultural components (Said, 1993).

Their visualization is consistent with Hegelian philosophy and Plato’s idealism when viewed in retrospect. They argued that the dominant class is ultimately responsible for finding a solution to a problem (Miller, 1969, pp. 583–584; Moramollu, 2016). In a related vein, Kimbell (2002, p. 22) clarified this by citing the words of American historian Prescott (1847), who lived in 1900:

The surest test of the civilization of a people—is to be found in their architecture, which presents so noble a field for the display of the grand and the beautiful works; and which simultaneously, is so intimately connected with the essential comforts of life.

This presumption depicts traditional or modern architecture as the products of communication and consumption, internalized as primary (denotative) and secondary (connotative) functions (Eco, 2013). The main driving force behind imperial ideology is to establish prototypes in colonies in order to exert authority and enforce obedience. Schools remain significant structures that influence class, culture, and society, though their impact is limited to certain boundaries. They serve as an efficient social mechanism for enforcing political control, often for hidden or unnoticed purposes (Cassirer, 1970, p. 90). According to Tafuri’s (1969) analysis, the manifestations of using the spirit of the age as a type of ideology that gained popularity in the early Enlightenment period followed systematic approaches and produced results, as explored by Özsu (2016), such as

-

i.

A naturalistic approach to urban planning created model-based city plans with a lack of multiple nuances for users to perceive diversity.

-

ii.

Political approach as an exclusive interest group focused on promoting order and solving city problems (for example, the Radiant City by Le Corbusier). This mathematical-based framework of design, when adopted in collective housing developments, has failed. The Pruitt-Igoe public housing case in St. Louis, Washington, 1960 (Newman, 1972) is a practical case where the ignored social symptoms of individual identity led to hazard perception and failure.

-

iii.

The Socialist approach created the industrial city as a utopia based on functional zoning, which various schools of architecture and urban planning use to articulate spatial zoning during the preliminary stages of the design process.

-

iv.

Order and a chaotic approach gave birth to the universal city, but despite different movements at the time, the principles were limited to unity, constructionist production, and consumption, which ultimately became urban social machines—the city as an organism and the city as a social organism.

-

v.

The urban mechanism version was the contribution of Le Corbusier’s realistic experiment, conceptualizing the architect as an organizer and not a designer of objects. An assumption that responded to the economic boom and technological innovations of the time.

Manfredo Tafuri believed that modern architecture was the result of a fusion between ownership and development. The suggestion received support from individuals who had a strong interest in modern art and believed in the world’s potential. Tafuri had both favorable and unfavorable views on capitalist ideology. These concepts are spread in various contexts, though, as a result of intellectual and cultural cross-pollination (Aureli, 2010). Ideology is hidden in works of architecture and colonizes its form, transforming it from “dynamism” to “commonality,” according to the structural perspective on the interaction between ideology and architectural development in the context of Soviet architecture (Petrulis, 2002). Ridley (2002, p. 188) argues that in colonies, Imperialism highlights Ancient Greek and Roman themes in architectural objects. India is an example of this. At times, they mix the meager vernacular features of the colony in an unequally diverse form (Jayewardene-Pillai, 2007, p. 14). The creativity of architects is constrained by this type of social positioning, which also directs contextual identity toward commercial goals. Today, the concept of grand theory in modern approaches dictates that practitioners’ built works in various urban contexts adhere to logical rules (Kellow, 2006). They disregard non-quantifiable subjective variables instead. This examination of the interplay between ideology and architecture is critical in nature and exhibits a flow of energy in both the form and volume of space. It represents a comeback of nationalism and imperialism in the guise of a new social structure.

Pluralistic cultural context of Gazimağusa-Cyprus

Cultural pluralism refers to the social, political, and legal institutions of a society and practices oriented to respect difference and value diversity in such a way that social cohesion is enhanced rather than threatened’ (Penman, 2014). It differs from cultural diversity because it aims to better understand cultural differences beyond just tolerance. Cultural plurality encourages the sharing of resources and social amenities without the assimilation of cultural groups within the territory. This phenomenon is associated with ideology because it merges with those of the humanities, social sciences, and religious circles. After World War I, the social order, which cultural pluralism tends to verify, failed in the hands of the British (Higham, 1984, p. 199). Although culture transcends politics (Kallen, 1915), the latter was turned upward in contexts such as Africa, Asia, and other colonies during British colonization. Cyprus before British Rule presents a cultural context with different communities coexisting with Greek Cypriots, Turkish Cypriots, Maronite, Armenians, Latins, and others (Akçali, 2007). This integral cultural composition has made universal Cyprus a unique, culturally pluralistic context. The cultural signs and symbols of these past civilizations to date represent a rich cultural journey from the earliest days of the Middle Ages.

The multiple structures of education that study human cultures energize national identity. It supports the formation of secular culture and integrates different forms of coexistence. During the British colonial era, secularization in Cyprus led to the emergence of a middle-class workforce that was envisioned as a way to improve public services and promote social mobility. Furthermore, the exclusion of appropriate measures for cultural contingencies within the island fueled the cultural divide between Greek-speaking Cypriots and Turkish-speaking Cypriots. Gates (1993, p. 473) juxtaposed this fact by identifying sociocultural extremes as the undeniable crackers of today’s world. In the city’s image, the classical signs in educational buildings serve to communicate classical values in settings and pay tribute to the ancient origins of knowledge (Schroeder, 2013, pp. 358–362). The British Administration treated the plural nature of Cyprus lightly in schools by allowing instruction in separate ethnic languages.

Their inaction in allowing schools to use motherland-based curricula is not outside the ideological box. Such an attitude drove the cultural context of Cyprus towards nationalist ideologies of “Hellenism and Turkishness.” The cultural ecosystem formerly knitted together has been repelled from the center to the edges. Homogeneity in school buildings in Cyprus from the late British Period to now provides a new cultural image that lines up with the global context, with varying contextual implications. It was also mixed with local sensitivities and environmental qualities during the early British period before the absolute shift to modernity (Bozdogan, 2001).

In some cases, such as for residential, public, or cultural endeavors, the change in context often highlights the fundamental roles that buildings play in city planning initiatives. This approach is in line with globalization, but it fails to give sufficient attention to the intangible factors that underlie these projects. A practice criticized for ripping into the identities of cities and their historical tissues. This pertinence in Gazimağusa erased historical patterns like narrow streets and the use of human-scale visual volumes and caused a loss of city identity (Nia and Suleiman, 2017). Urban development in this context during the British Period underwent a broad physical transformation. The aspects of urban systems that have changed fall into four categories:

-

The peasant and fishing town changed into a commercial city through the harbor and tourism developments around the waterfronts of Varosha (Doratli et al., 2003).

-

The transportation of goods from Famagusta to Nicosia, the capital, transitioned from using beasts of burden to the steam engine train. (Orr, 1972, pp. 152–159).

-

A shift from vernacular styles of architecture to modern styles and construction techniques for administrative buildings, as exemplified in the Municipal edifice of the context (Fig. 1). This new identity created a cultural and visual distinction between the old city and the new urban neighborhood. Modernity dominated the housing development of Varosha Town (Phohaides, 2004, pp. 2–3), but it closed for more than four decades because of the communal war.

-

They built secondary schools to reduce the burden of parents and their children traveling to the state capital for secondary education (Ukabi, 2015).

This study contextualizes the cultural pluralism of Gazimağusa as a cultural energy that was downplayed by colonists but still had a significant impact in the context due to their nationalistic tendencies. During prior periods and histories, identity in this context retained a multicultural and multilingual character even before the frequent visits of pilgrims, merchants, and other modern artists. This place provided opportunities for masons, shoemakers, writers, multiple faith practices, and trade between the East and West (Coureas, 2005, p. 67). The city attracted the English playwright William Shakespeare for popular theater performances at Othello Castle; an example of such a play is ‘Domestic tragedy in Othello’ (1603–1644). Gazimağusa’s Levant image of diversity and flexibility was reflected in the cross-cultural pollination that created prosperity, driven by the ideology of ‘deal before ideas.’ Today, such a label can be associated with city branding if viewed in a wider socioeconomic context. It highlights the importance of buildings in society.

Consensus always exists on fundamental issues, despite the merchants’ description of the city as a transitory place where people exchange goods, concepts, and texts before dispersing (Hoffman, 2007, pp. 1–8). A label that still resonates with many migrants to Cyprus. When an epidemic breaks out, common ground is always found on matters of language, political difference, defense, and communal solemn worship (Edbury, 1999, p. 337). The preservation of each group’s identity was crucial to the setting’s Outstanding Universal Value among cultural groups (Walsh, 2013). Varosha’s urban and tourism developments were sparked by the emergence of a novel way of thinking and an avant-garde architectural style. The communal war and the 1974 divide retarded the urban development of this neighborhood. In spite of these cultural manifestations, its magnetic spirit of attraction bears roots in ideology in both major communities. In 1974, the division of Cyprus resulted in Gazimağusa also becoming divided. As a result, the concept of vocational education emerged, with more schools being established in the Canbulat neighborhood than in any other area of Gazimağusa. This post-war approach aimed to promote practical skills and training opportunities for students to meet enormous manpower demands.

Methods

This qualitative research employs an interpretative case research approach, which integrates the ideological linguistic concept of cultural texts through reviews of school-building examples from Cyprus during the British period and case studies from Gazimağusa on the northern side that were also constructed in the same era. A search for a suitable approach led to previously used three approaches: the descriptive approach (Özgüven, 2004; Aydinlik and Pulhan, 2019), the historical-interpretative approach (Djokić et al., 2016), and the investigative approach (Bilsel and Dinçyürek, 2017). In order to frame a suitable method for this paper, cross-pollinating these approaches in such a way that incorporates context evidence and interprets scenarios on one side of a range was central. It also corresponds with Bhattacherjee’s (2012, p. 105) social research framework, allowing for the use of an interpretative case approach that incorporates descriptive and historical elements. This researcher stressed that the approach is well suited for exploring the hidden reasons behind complex, interrelated social processes for which quantitative evidence is difficult to obtain. School buildings were selected because of their resilience throughout the history of civilization and because they constitute a friendly backbone for the transmission of ideology and the development of a culture of social change. Accessing 14 school examples from the documents of previous work on Cypriot architecture (Georghiou, 2018, pp. 124–188), as a comparative technique to appraise the treatment of school buildings when Cyprus was not partitioned (Table 1). These examples will enrich the analysis and discussion of selected cases within the Famagusta context.

From the Table: The many schools in Nicosia during the British colonial era are in fact associated with being the administrative capital of Cyprus before and during this civilization and responding to both ideological aspects of power, as well as urban demographic and economic indicators. The next step engages with the analysis of seven case studies from Gazimağusa of school buildings built during the British period. The study was limited to four neighborhoods within this cultural context, and the numbers of the selected cases are shown on the Map as shown in Fig. 2. and their brief information is compiled in Table 2.

From Table 2, the distribution of the cases from the study area followed the following order: Canbulat district has four cases, while the other three districts (The Walled City, Dumlupinar, and Baykal) have one case each. More schools were built toward independence in 1960, and their character is marked by lightness, openness for social interaction, and freedom, but in either direction, the school buildings are linked to different types of ideologies. The selection criteria for the cases considered were:

-

The period of construction of the school, which in most cases is printed on the entrance gate of the school or on the facade of the school building.

-

Their contextual location in the city is a form of cultural ecosystem for connection and, at the same time, evolution from the old context to the new context. The historic city maintains its fortification character as a form of boundary within the whole, but the growth of the city towards the Canbulat and Varosha neighborhoods signifies social prosperity.

-

The school types are categorized according to their level of education (elementary schools, secondary schools, and vocational schools) and functional structure.

-

Schools that are not reused for other functions by the new owners (the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus government).

The analysis of the selected cases followed the visual variables of the facade:

-

1.

The facade character of the school buildings to trace their styles and interpret how these instill cultural or ideological perceptions

-

2.

Explored the visual features of the facade and secondary elevation of each case through technical observations. This process can inspire new conceptual thinking beyond the conventional ideas identified in the literature we have researched. Such features include signs, symbols, or concepts that act as signifiers in a cultural and ideological sense. This technique relates to the type used to evaluate societal language as a semiotic construct from cultural materials (e.g., signs, images, lyrics, etc.).

Results

The case studies analyses are provided by their visuals, the facade, and an additional view of concrete evidence in each case.

Endustri Meslek Lisesi (case 1)

This school building features two unique facades. The south facade, built in 1906, directly faces the Varosha neighborhood and is a two-story building in the Neoclassical Greek Revival style with a pitched roof. The north facade, completed in 1960, overlooks the Canbulat neighborhood, a residential quarter that grew with modern trends back-to-back with Varosha’s rise to prominence in the mid-1960s. An Art Deco style, with Palladian architectural elements arranged like spiral stone steps towards the porch, defines the facade focal point for the entrance. The Greek triangle is a symbol of mythology woven into the facade. The pediment rests on a hexastyle ionic portico on a pedestal of six steps. The framework of the facade is entirely decorated with moderate-sized glazed bay windows with symmetry on both sides of the entrance. The windows are rounded with pilasters and painted white for the south facade and green for the north facade. Horizontal drip moldings run along the facade to differentiate floor-to-floor heights (Fig. 3).

Gazi İlkokulu (case 2)

The facade of this school building highlights the characteristics of Neoclassicism and the Greek Revival. The central positioning of the raised entrance in tetra-style ionic order created symmetry on the facade. Two sets of three panels of glazed bay windows separated and rounded by ornamented pilasters on both sides of the entrance are clearly visible on the facade. The ancient Greek triangle symbol and the Queen of England’s symbol are attached centrally to the pediment of the cornice of this facade and are repeated on the north and south sections of the school building (Fig. 4).

Canbulat Özgürlük Ortaokulu (case 3)

The facade of this school building depicts an early modern style in the architecture of the schools in Famagusta. The facade displays elements of the Doric order, but these traditional features are not hindering the school’s move towards a dynamic identity that encourages innovative thinking about the world. And so, openness in the appearance of the facade started to manifest as an integrated whole for the efficient socialization of students. The entrance has been updated with a reinforced concrete cantilever canopy that sits on a raised concrete base. The metal-glazed door is now illuminated, and the solid columns have been removed, reflecting modern building design principles. The use of arts and crafts elements is shown to enhance the esthetics of the facade, composed of open terraces on both floors. The placement of creamy dwarf piers stands in between wide casement windows as non-structural elements differentiated from the vertical structural members by the use of maroon emulsion paint. The top portion of the facade maintains the principles of horizontality with a straight-lined, flat, reinforced concrete roof Fig. 5.

Polatpasa İlkokulu (case 4)

The facade traces a modernist style that disconnects from copying the temple-like colonial character despite belonging to a missionary school. The common entrance has been redesigned for storage purposes. However, the reinforced concrete floating canopy above it is supported by inclined, circular double columns made of reinforced concrete at both ends. As a substitute, two simple doors are opened on both sides of the entrance as part of the facade’s defining elements, this time, leading to the terraces. The modifications are finished with aluminum and glazed paneled skin, giving the facade a new expression and giving the students a new material experience with a flat roof that obeys modern horizontality principles (Fig. 6).

Alasya İlkokulu (case 5)

Modern features are present on the facade of this school building, and the entrance is more inclusive with its transitory qualities knitted and configured with lightweight elements. Similarly, all other exit points within the building received the same treatment. The facade of this building is without decorations but is characteristically sensitive to the climatic indicators of the context, with a solid building facade line and patterns of small bay window openings fully glazed. The repetition of the window openings and the use of colors created a composite expression. The combination of corrugated iron sheets with a flat roof introduced another visual aspect to the facade. The color contrast between the right side of the entrance painted white and the left side painted maroon defines the transition from the old block to the new additions. The current owners preserved this facade feature for its integrity value (Fig. 7).

Sehit Huseyin Akil İlkokulu (case 6)

The modernist style continues in this school with its greater openness to the outdoors. This allows the inner terrace elevation to be more interactive than the facade. This could be a strategy to keep students away from the distractions of passersby and vehicular movement. Facades with an emphasis on a common entrance disappear from public view. The colonnaded terraces (conceptualized from the visual expression of the facade) flow without decoration, echoing the new ideological influence on school buildings. A lean-to-roof feature subtly began to appear as a subset of the entire facade profile. Glazed bay windows that are rounded with stone moldings contribute to the character of the facade (Fig. 8).

Gazi Magusa Meslek Lisesi (case 7)

The characteristics of postwar modernism are demonstrated in this facade: The use of precast vertical piers, continuous horizontal hoods, and segmented arches painted in leaf green enhances the shading of the large glazed window openings. The entrance’s focus is fashioned into a modernist symbolic canopy of two square columns. It carefully projects the terrace over to the front door and gives the facade an asymmetrical appearance. A crate-like screen wall on the right side of the facade acts as the sun-breaker, provides semi-privacy to users (Fig. 9), and aligns with post-war architecture, as argued by Aydinlik and Pulhan (2019).

Discussion

The highlights from de Raul’s lecture modules simplify some fundamental ideologist theories. The British involvement with schools in Gazimağusa shows that they disagree with Antonio Gramsci’s conceptualization of ‘cultural intermediaries.’ According to a paraphrase of that theory, the bourgeois use social institutions like schools to inculcate their ideas and values (de Raul, n.d.). Moreover, in the cultural context studied, the interaction of ideology in school buildings agrees with the ideological postulates of Karl Marx and Louis Althusser’s ISA-ideological State Apparatus. The former advocated class control, consciousness, and communication and used school buildings to entice the subject. In contrast, the latter re-conceptualized schools as a basis for political power orders and a realm for grooming ideologies.

The British used school buildings to spread cultural messages throughout their colonies during the colonial era because they saw them as symbols of culture. These initiatives, however, were abandoned as a result of the political shifts brought about by decolonization. By restricting access to specific social classes, especially the ruling class, the ruling class was able to capture this type of ideology.

The imperialist control of schools did not start with the British period; the previous Ottoman Rule was in charge of the İdadi school and Lycee school in Nicosia (Lycee is now reused for the TRNC Tourism Office). From the cases analyzed, two typological facade entrance expressions are obvious among the cases analyzed:

-

Centrally positioned entrance pattern: Shows an eminent use of the Porch as a facade focal point. Cases 1, 2, and 7 are examples of schools with such character and correspond with the Early British Period ideology in school buildings (1878–1925).

-

Diversified entrance pattern: The character is an open and freer facade that engages hanging elements as shade to define the main entrance. Cases 3–6 were found in this category and align with the late British Period approach to the facade expression of school buildings (1925–1960).

The cases analyzed and the examples reviewed from the documents also match the label of 1924 as the demarcation between the Early British Period and the Late British Period in the school buildings of Gazimagusa and Cyprus. This year also marked the end of Neo-Gothic or Neoclassical school buildings, which was a response to the 1931 riot. This outcome agrees with the schools built during the British Administration in other cities of Cyprus, such as Nicosia, Paphos, and Limassol. Likewise, the representation of the Greek triangle symbol and colonial signs on the facade of the school buildings came to an end. A comparison of these findings with the data in (Table 1) shown previously gave the following highlights:

-

Endustri Meslek Lisesi (case 1), the architectural expression is similar to the schools designed by Theodoros Photiades in Nicosia and Paphos during the British Period; “see Table 1 (code: b,c,d,l).”

-

Gazi İlkokulu (case 2), designed by Theodoros Photiades, shows an architectural expression resembling that of (Case 1) and the ones built at Paphos and Nicosia by the same architect; “see Table 1 (code: b–d,l).” The Greek triangle and Queen of England cultural symbols placed on the school buildings reflect imperial ideology in the cultural context of the colonies.

-

Canbulat Özgürlük Ortaokulu’s (case 3) facade shows a stylistic shift from Neoclassical to Modern style in the school buildings of Gazimagusa. This school’s design is similar to those made by the Rousou and Pericleous Firm between 1950 and 1955, as well as the one in Nicosia designed by Turkish architect Ahmet Behaeddin. Available in “(Table 1 with the codes: e–g).”

-

The Polatpasa Ilkokulu (case 4) pays tribute to the Terra Santa College in Acropolis, Nicosia, designed by G and U Durati around 1953–1956, “see Table 1 (code: j)” with modern style features and expressions.

-

Alasya İlkokulu (case 5) corresponds with the schools in other cities of Cyprus built from 1953–1960. The emphasis on facades shifted to functional zoning, which obeys the socialist approaches to city planning reviewed in the literature that created the Industrial City. The concepts of esthetic, functional, and sociocultural context are rationally merged in a way that connects with the new urban fabric.

-

Sehit Huseyin Akil Ilkokulu (case 6) displays a more organic modern facade for social cohesion than the style adopted in the early British Period. The configuration of the facade does not conform to the other 14 schools reviewed.

-

The Gazi Magusa Meslek Lisesi (case 7) was originally named Terra Santa School as part of the Mission Secondary and “school for ladies, “ see Table 1 (code: m).” Now converted to a vocational school with a mixed student intake, Architect Stavros Economov designed this school in a postwar modernist style (which agrees with the earlier findings by Aydinlik and Pulhan, (2019), with compactness and a sensitive facade to the context’s climatic conditions.

The results also show that significant schools in Gazimağusa and in Cyprus were designed by architect Theodoros Photiades during the Early British period; this paper interpreted this as a lack of Turkish Cypriot architects in Cyprus during that period. In continuity, the 1950 school buildings show a shift in the style of school architecture to the Modernist style and agree with the school commissions handled by Rousou and Pericleous Firm. Although their school designs followed modernist language in other parts of the island in a pure internationalist style, the Gazimağusa scenario evolved conceptually in contrast with the present-day expression (copying the international approach). Such evidence contradicts architectural critics’ popular and one-sided position, which completely miscalculates all modern styles as international styles. This stance was traceable to Tafuri’s assertion during the early Enlightenment period, although with reservations over some of the approaches used for city development in that era. These findings show that Gazimağusa school buildings were under the influence of secularization but, by application, did not showcase purely an international style but a conceptualized modern style of architecture. It was used in schools and government buildings in other cities in Cyprus. It was later internalized in Cyprus as Mediterranean modernity, as evidenced by the work of Gurdalli and Koldas (2015).

Ideology manifested in Gazimağusa at two levels: urban (sociological and other works of art) and architectural (school buildings and other typologies) during the British period. A breakdown of the impacts from each dimension is below:

At the urban level of the context:

-

i.

Traditional fishing and subsistence farming occupations shifted to tourism and commercialization, which affected the area’s sense of place.

-

ii.

Urban fragmentation through individualistic housing design and construction and new urban sprawl away from the Walled City towards the Varosha and Canbulat neighborhoods as new cities with modern standards of living delineated in a modern architectural expression became the practice norm.

-

iii.

Intrinsic living which references modern life, is now widespread in the various Mediterranean districts of Northern Cyprus.

-

iv.

Transportation of goods was upgraded from crude methods to mechanical means with the steam engine train narrowing the distance between the seat of power (Nicosia) and Famagusta.

At the architectural scale of the context:

-

(I)

Transformation of traditional school buildings into modern ones; embracing dynamic educational strategies

-

(II)

Schools echo the social class mentality of the educated middle class, allowing motherland-based curricula and gender separation for school types. A social–cultural modification that broke the bonds of pluralistic principles and gave rise to a culturally based nationalistic revolution.

-

(III)

The use of concrete as a new material replaced ornamentation. Planer elements transformed the facade’s expression into a secular identity. At present, all newly built schools in the TRNC display a common cultural symbol: the bust of Ataturk Kemal (the Turkish leader of “Kemalist Nationalism”).

Based on the facts highlighted, this paper argues that the application of image elements and the adoption of styles introduced into Gazimağusa school buildings during the British period indicate two characteristics: The Early British period displayed homogeneity (cases 1, 2). Interpreted as the cultural symbols of British Imperial ideology in the architecture of the colony and aligns with the situation of India that was under the British Empire, as mentioned in the literature. The Late British Period was heterogeneously configured (cases 3–7). However, this deduction requires further investigations into schools that were under other types of British colonization like Dominion (Canada, South Africa, etc.) and Protectorates (Nigeria, Brazil, etc.) to ascertain their ideological tendencies since this paper focused on schools in a Crown Colony.

In the area of teaching, the paper submits that leaving the language of instruction to ethnic preference (Greek and Turkish) and unstructured curricula endangered community cohesion. The prosperity gains of the educated middle class propel an identity crisis between the workers and the peasant farmers. Furthermore, the flow of cultural energies between a ‘single ethnic group and another’ became unbearable, and feelings of cultural assimilation became obvious among economically disadvantaged groups.

Conclusion

Based on the social and communication potentials of architecture, this study hypothesizes that traditional teaching methods correspond with conventional school buildings on the one hand, while modern educational concepts relate to creative school buildings on the other. The former interpretation agrees with the schools built during the Early British period, and the latter inference aligns with the Late British period in Gazimağusa. The shift in identity in this context was not isolated from the phenomenal architecture of school buildings in other European countries. The study argues that Famagusta was linked to the spirit of the time through the architecture of the schools. The British campaign for secularism while neglecting the cultural composition of the pluralistic context showed a lack of empathy for the locals’ identities, which afterward was consequential to the Cyprus divide. The ideological agenda was to bring positive outcomes by raising the educated class into civil service functions as a part of structural ideology, which previous administrations failed to achieve. Moreover, this appealing outcome through schools in turn supported their clever planting of the signs and symbols of imperialism as a negation of cultural plurality.

The emergence of Enosis (Hellenism) and Kemalistic (Turkishness) nationalistic movements, driven by ideology, had a profound impact on the cultural ecosystem of this context, causing people to reflect on their sense of identity. The earlier use of school buildings selectively reflected the existing vernacular character of the context and proportionality of local materials, such as the use of a traditional school building as a reference point for the construction of the new ones. However, the subtle piercing of the visual character in introducing liberal notions connected Gazimağusa to modernist ideologies and the development of the modern world as a whole. The foundation laid for modernism soon dominated the architecture of schools and other building typologies during the late British Period. The use of rational methods to create esthetics and the experimentation with concrete-modern materials in that era were used to replace vernacular themes in school buildings and the construction of new buildings in the city.

This tendency opened Gazimağusa in Cyprus to imitating a global identity still connected to avant-garde philosophy. Based on these cultural inconsistencies, sociocultural signs and symbols have been removed from school buildings except for the portrait sculpture of Ataturk in Northern Cyprus. The homogenization of school buildings today is not new. In contrast, the factor of sameness presents a mixed feeling in the context’s visual layering, upon which today’s school buildings have drifted to a style that negates architecture in context (especially on the psychology of students and way-finding) and is a major cause of concern in the overall school buildings. The assimilation of cultural hierarchies in school buildings requires further interrogation at the regional level to assemble broader empirical data to draw generalizations that challenge the findings of the present study. Since ideology keeps evolving with time, this paper calls on policymakers from Gazimağusa, Northern Cyprus, and other Cypriot leaders to develop cultural cooperation, re-evaluate the architecture of schools in the multicultural context, and develop a consistent values-based architectural language. Likewise, education regulators and the urban development unit of Northern Cyprus needed to build a consensus that would address the homogeneous architectural identity of present-day schools and the importance of the local communities in their development plans. The architects will need to formulate school designs with multiple cultural layers to ensure contextual richness, the health of students, and the sociocultural values of the region and the whole island.

References

Agrest D, Gandelsonas M (1973) Semiotics and architecture: ideological consumption or theoretical work. Oppositions 1(1):93 –100

Ajepe I, Ademowo AJ (2016) English language dominance and the fate of indigenous languages in Nigeria. Int J Hist Cult Stud 2(4):10–17

Akçali E (2007) The ‘Other' Cypriots and their Cyprus questions. Cyprus Rev 19(2):57–82

Althusser L (1970) Ideology and ideological state apparatuses. In: Notes toward an investigation, Lenin and philosophy and other essays, (1971) Brewster B (trans) and Blunden A (transcribed). Monthly Review Press, New York, Pp. 121–176

Argyrou V (1996) Tradition and modernity in the Mediterranean, the wedding as symbolic struggle. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Aureli PV (2010) Re-contextualizing Tafuri’s critique of ideology. Log 18:89–100. Available via DIALOG. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41765325. Accessed 5 May 2023

Aydinlik S, Pulhan H (2019) Education in conflict: postwar school buildings of Cyprus, in ‘War and Cities’. Open House Int 44(2):68–76. https://doi.org/10.1108/ohi-02-2019-b0009

Barthes R (2009) Mythologies. Vintage and Random House, London

Bhattacherjee A (2012) Social science research: principles, methods, and practices. University of South, Florida, p. 105

Bilsel N, Dinçyürek Ö (2017) Education under the shadow of politics: school buildings in Cyprus during the British colonial period. Paedagog Hist 53(4):394–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2017.1290664

Bozdogan S (2001) Modernism and nation building: Turkish architectural culture in the early Republic. University of Washington Press, Seattle

Bozkurt U, Trimikliniotis N (2014) Incorporating a class analysis within the national question: rethinking ethnicity, class, and nationalism in Cyprus. Nationalism Ethn Polit 20(2):244–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/13537113.2014.909162

Byrant R (2004) Imaging the modern: the culture of nationalism in Cyprus. I. B. Tauris & Co Ltd, London

Carr AW (1994) Art in the Court of the Lusignan Kings. In: Cyprus and the Crusades, Coureas JN, Riley S (eds). Society for the study of the Crusades and the Latin East and Cyprus Research Centre, Nicosia, p. 250

Cassirer E (1970) An essay on man. Ban, New York, p. 90

Coureas N (2005) Economy. In: Cyprus: society and culture, Nicolaou-Konnari A, Schabel C (eds), Medieval Mediterranean (58). Brill, pp.103‒156. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789047416241_005

de Raul (n.d.) Theories of ideology in cultural studies. Azim Premji University

Djokić V, Trajkovic JR, Krstić V (2016) An environmental critique: impact of socialist ideology on the ecological and cultural sensitivity of Belgrade’s large-scale residential settlements. Sustain 8(9):914

Doratli N, Hoskara S, Zafer N (2003) The Walled City of Famagusta (Gazimagusa): an opportunity for planned transformation. In: Petruccioli A, Stella M, Strappa G (eds), ISUF 2003, the planned city?. Uniongrafica Corcelli Editrice, International Seminar on Urban Form (Organization), Bari., pp.3-6

Eco U (2013) Function and sign: semiotics of architecture. Available via DIALOG. https://marywoodarchtheory.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/function-and-the-sign-the-semiotics-of-arch_u-eco.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr 2020

Edbury PW (ed) (1999) Kingdoms of the Crusaders: from Jerusalem to Cyprus. In: Variorum collected studies, vol 653. Ashgate, Aldershot, p. 337

Ergut TE (1999) The forming of the national in architecture. METU JFA 19(1–2):31–43

Foka Z (2020) The space in-between: tracing trans-formative processes in Nicosia’s Buffer Zone. Dissertation, Bauhaus University

Gates H (1993) The debate has been miscast from the start and Current issues and enduring questions. In: Barnet S, Bedau H (eds) A guide to critical thinking and argument, with readings (1991). St. Martin’s, Boston, pp. 473–477

Georghiou C (2018) The architecture of the Cypriots during British rule 1878–1960. En Tipis, Nicosia, pp. 124–188

Gurdall H, Koldas U (2015) Architecture of power and urban space in a divided city: a history of official buildings in Nicosia/Lefkoşa. Design J 18(1):135–157. https://doi.org/10.2752/175630615X14135446523387

Higham J (1984) Send these to me: Jews and other immigrants in urban America. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, p. 199

Hoffman RR (2007) Introduction: remapping the art of the Mediterranean and Late Antiquity and Medieval Art of the Mediterranean World. Blackwell, Malden, MA, pp. 1–8

Holland R, Markides D (2006) The British and the Hellenes: struggles for mastery in the Eastern Mediterranean 1850–1960. Oxford University Press, New York

Hook GD (2015) Protectorate Cyprus: British imperial power before World War I. I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, London

Jayewardene-Pillai S (2007) Imperial conversations: Indo-Britons and the architecture of South India. Yoda Press, New Delhi, p. 14

Kallen HM (1915) Democracy versus the melting pot. The Nation 100(2):217–220

Kellow P (2006) The ideology of architecture. INTBAU 1(15):1–23

Kimbell R (2002) Architecture and ideology. N Criterion 21(1):4–11

Luke H (1989) Cyprus under British Rule. Harrap, London

Malinowski B (1960) A scientific theory of culture. Oxford University, New York

Miller AV (1969) George Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel: The Science of Logic. George Allen & Unwin Ltd; Humanities Press, London, pp. 583–584

Moramollu G (2016) Ideology and literature. Humanit Soc Sci Rev 6(1):455–460

Newman O (1972) Creating defensible space. Center for Urban Policy Research Rutgers University, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Office of Policy Development and Research

Newman P (1953) A short history of Cyprus. Longmans Green & Co, London, pp. 200–210

Nia HA, Suleiman YH (2017) Identity in changing context: factors of losing identity in new developed part of the city of Famagusta, North Cyprus. J Contemp Urban Aff 1(2):11–20

Orr CWJ (1972) Cyprus under British Rule. Zeno Publishers, London, pp. 152–159

Özgüven B (2004) From Ottoman Province to the Colony: Late Ottoman Educational Buildings in Nicosia. METU JFA 21(1–2):33–36

Özsu C (2016) ARCH 222 presentation of Manfredo Tafuri/Toward a critique of architectural ideology (1969). TED University. Available via DIALOG. https://cerenozsu.wordpress.com/2016/04/23/toward-a-critique-of-architectural-ideology1969-by-manfredo-tafuri/. Accessed 5 May 2023

Pantelić B (1997) Nationalism and architecture: the creation of a national style in Serbian architecture and its political implications. J Soc Archit Hist 56(1):16–41

Penman R (2014) Cultural pluralism. Key concepts in intercultural dialogue 15. Center for Intercultural Dialogue. Available via DIALOG. http://centerforinterculturaldialogue.org. Accessed 20 Apr 2020

Petrulis V (2002) City and Ideology: Soviet Kaunas of 1945–1965. Available via DIALOG. http://www.eki.ee/km/place/pdf/kp3_13_Petrulis.pdf. Accessed 20 Apr 2020

Phohaides P (2004) Architecture and modernity in Cyprus, pp. 2–3. Available via DIALOG. http://www.academia.edu/4987823. Accessed 20 April 2020

Prescott WH (1847) History of the conquest of Peru. Public Library UK, Boston

Pollis A (1998) The role of foreign powers in structuring ethnicity and ethnic conflict. In: Calotyches V (ed) An unimaginable community, 1955–1997. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

Ridley J (2002) Lutyens, New Delhi, and Indian Architecture. In: Lutyens Abroad,, Stamp G, Hopkins A (eds) British School at Rome, London, p. 188

Safty A (2011) The Cyprus question: diplomacy and International Law. İUniverse, Bloomington

Said EW (1993) Culture and imperialism. Vintage Books, New York

Schroeder JE (2013) Building brands: architectural expression in the electronic age. In: Scott LM, Batra R (eds) Persuasive imagery a consumer response perspective. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, London, pp. 358–362

Shusterman R (2009) Aesthetics and postmodernism. In: Levinson J (ed) The Oxford handbook of aesthetics, ebook. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199279456.003.0047

Singh G, Rex J (2003) Pluralism and multiculturalism in colonial and post-colonial society-thematic introduction. Int J Multicult Educ 5(2):106–118. http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0013/001387/138796e.pdf

Smelser NS, Baltes PB (2001) Ideology: political aspects. Elsevier International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Available via DIALOG. https://www.elsevier.com/books/international-encyclopedia-of-social-and-behavioral-sciences/smelser/. Accessed 20 Apr 2020

Šuvaković M (2014) General theory of ideology and architecture. In: Mako V, Blagojević MR, Lazar MV (eds) Architecture and ideology. Cambridge Scholars, Newcastle, UK, pp. 2‒12

Stillwell R, MacDonald WL, McAlister MH, Princeton NJ (1976) The Princeton encyclopedia of classical sites: ARSINOE Cyprus. Princeton University Press

Tafuri M (1969) Toward a critique of architectural ideology. In: Hays KM (ed) Architecture theory 1968. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 6–35

Terry E (1991) Ideology: an introduction. Verso, London, pp. 4‒23

Thomas A (2015) Imperialism—a dictionary of modern architecture (course assignment blog for ARTH15709—20th century Western Architecture). University of Chicago. Available via DIALOG. https://www.voices.uchicago.edu/201504arth15709-01a2/2015/11/16/i/. Accessed 20 Apr 2020

Tofallis K (2002) A history of Cyprus from ancient times to the present. The Greek Institute, London, pp. 76–104

Ukabi E (2015) Comparative study on the British Colonial School Buildings in Old Calabar (Nigeria) and Famagusta (North Cyprus). Dissertation, Eastern Mediterranean University

Walsh MJK (2013) A spectacle to the world, both to angels and to men: multiculturalism in Mediaeval Famagusta, Cyprus, as seen through the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste. J East Mediterr Archaeol Herit Stud 1(3):193–118. https://doi.org/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.1.3.0193

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EBU handled the conceptualization, methodology, analysis, sourcing for research materials, writing of original draft preparation, visualization, revisions, and writing of revised copies. HG meticulously guided the formation of conceptualization, sourced materials, and reviewed the whole drafts and final revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ukabi, E.B., Gurdalli, H. Implications of ideology on school buildings and cultural pluralistic context of Gazimağusa, North Cyprus. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 734 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02220-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02220-w