Abstract

While it is known that researchers need to contend with increasing demands in the evolving landscape of higher education in the UK, few studies have examined how academic researchers discursively construct their struggles. This paper explores the valuation discourses that academic researchers draw upon to construct and account for their struggles in the process of establishing themselves as academics. It strives to answer the question: What kinds of struggles do academics face when positioning themselves and their research in relation to disciplines? What kinds of valuation discourses do academic researchers draw upon to position themselves as academics working in certain disciplines? The data comes from my PhD research, where I conducted 30 qualitative interviews with academic researchers ranging from PhD students, early career researchers to Professors Emeriti, who work in applied linguistics and language-related fields in UK universities. This paper focuses on two case studies of academics who positioned themselves as “mavericks” or who resist being pigeonholed in one discipline. In order to provide some comparative basis, the two case studies come from two ends of the academic career spectrum. I examine how they constructed their struggles with positioning themselves in relation to disciplines, and the kinds of valuation discourses evoked in the process. The paper proposes a model that conceptualizes how disciplinary positioning struggles are constructed by discursive acts and in the process, produce and reinforce valuation discourses about academic disciplines. Embedded in these disciplinary positioning struggles, researchers employed academic categories (Angermuller, 2017. High Educ 73(6):963–980) and evoked valuation discourses. The paper illustrates how academics hold valuation discourses about the kinds of disciplinary positioning practices that are valued, which may sometimes differ from the valuation discourses of fellow researchers, institutions and other stakeholders in higher education. The paper argues that such incongruence in valuation discourses between the individual and others result in positioning struggles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Like all other professions, academic researchers face their fair share of difficulties at the academic workplace. In order to be known as an academic researcher, one needs to be recognized as having expertise in a disciplinary field (Angermuller, 2013; Hah, 2019). A key struggle in the academic profession revolves around claiming expertise and positioning oneself in relation to a discipline (Hah, 2018) or what this paper termed as disciplinary positioning. Many researchers grapple with this throughout their careers as they find themselves having to communicate their research and themselves as researchers to their colleagues, to institutions, research grant providers, the public and other audiences. It is possible that throughout their careers, academic researchers constantly grapple with finding the best ways to position and re-position themselves in order to be recognized as possessing expertise in a certain discipline or field and above all, be recognized as a ‘legitimate’ researcher (Archer, 2008).

To some extent, claiming membership of a discipline is essential to identify oneself as an academic researcher. However, questions arise when academic researchers do not perceive themselves as falling neatly into the fields and departments that are demarcated or created by institutions. How do academic researchers negotiate their disciplinary positioning in relation to these socially constructed categories? This paper focused on two case studies of academics who positioned themselves as resisting being pigeonholed in one discipline or “mavericks” (in one participant’s words). I examined how they positioned themselves in relation to disciplines, and the kinds of valuation discourses they evoked in their positioning practices. In order to provide some comparative basis, the two case studies come from the same field (i.e. Applied Linguistics) and from two stages of the academic career spectrum. One is an early career researcher in his first academic job and the other is a retired professor.

This paper focuses on the valuation discourses that these two academic researchers evoke to construct and account for their struggles and in the process, position themselves as academics. The paper asks the following questions: How do academic researchers construct their struggles with disciplinary positioning in the process of establishing themselves as academics? For early career researchers (ECRs), this would emerge in their experiences with obtaining the first academic job. What kinds of valuation discourses do academic researchers draw upon to account for their disciplinary positioning struggles?

This paper argues that the ways in which academic researchers construct and account for their disciplinary positioning struggles can reveal their valuation of certain academic practices over others. Respondents position themselves vis-à-vis others and through a negotiation of meaning with the interviewer. This process of meaning-making often required tacit knowledge and evoked shared (or sometimes unshared) discourses about academia. What is implicit knowledge in an interaction or shared knowledge often comes from discourses (Van Dijk, 2011) and this paper argues that these discourses often constitute some degree of valuation. Such valuation discourses come from academics’ ways of evaluating which kinds of research programme and academic practices are better than others. At times, researchers positioned their personal valuation discourses as differing from what they think other stakeholders—such as recruiting panels, institutions, funding agencies, the REFFootnote 1, or the public—value.

But why is it important to find out what academic researchers value? Discourses are produced and reproduced through social practices. Discourses about academic practices influence how decisions are made in academia such as evaluation, citations, recruitment and many more other practices (Angermuller, 2017). In turn, academic researchers’ discourses about these practices are reproduced through talk—at meetings, conversations with peers, supervision of students’ work, gossip and many more. Valuation discourses in academia establish what are accepted as more valuable and desirable, and these discourses are reinforced over time. For my respondents, these discourses come from and contribute to the formation of their social realities under specific circumstances, working at a particular institution, during a certain period of time. In other words, they made sense of their experiences based on their understanding of what is happening in the wider landscape of higher education in the UK.

Overview

This paper begins by providing a background to discourses that could be drawn upon as tacit knowledge by academic researchers to construct and account for their struggles. The impact of disciplines on academic identities is explored. Following a discussion on the interactional approach taken to analyse the data, this paper proposes a discursive model to illustrate how valuation discourses and disciplinary positioning struggles relate together. Next, the paper explains how the data was collected and the methodology taken to analyse it. The analysis examines excerpts selected from interviews with two case studies to illustrate how they construct their struggles through discursive acts and evoking tacit knowledge about academic practices. The paper ends with a discussion of the kinds of valuation discourses embedded in how academics talk about their struggles. Finally it concludes with how valuation discourses can discursively enact an academic’s positioning.

Literature review

Discourses underlying academic struggles

Following Foucault’s notion that discourses are discontinuous and are thus products of history (Foucault, 1971), Gee proposed that every time people speak and act, they give “a voice and body to a Discourse” and ultimately “changes it, through time” (Gee, 2015, p. 180). Gee made a distinction between small ‘d’ discourses and big ‘D’ Discourses. He defined small ‘d’ discourse as any stretch of text or talk while big ‘D’ Discourse is a “socially accepted association among ways of using language, other symbolic expressions, and ‘artefacts’, of thinking, feeling, believing, valuing, and acting that can be used to identify oneself as a member of a socially meaningful group or ‘social network’, or to signal (that one is playing) a socially meaningful ‘role’, or to signal that one is filling a social niche in a distinctively recognizable fashion” (Gee, 2015, p. 178). Hence, academic researchers are recognized as researchers by the ways they think about and value certain academic practices. Discourses about academia are thus socially accepted ways of using language, valuing and positioning oneself as members of the academic profession. Thus the paper aims to uncover the valuation discourses of two academics working in the applied linguistics field in the UK, by considering these questions: How do academics position themselves in relation to disciplines? What do they struggle with in the process? What valuation discourses about academia do researchers draw upon to account for their disciplinary positioning and struggles?

Valuation in academia has been studied by various scholars in terms of citations (Hyland and Giuliana, 2009), recruitment and promotions (Lamont, 2009), remuneration (Angermuller, 2017) and in terms of scientific or academic capital (Lucas, 2006). Valuation discourses in academia are essentially what academics value in terms of academic practices. These discourses could be understood as ways in which researchers estimate and weigh the worth of particular practices in academic life and as such constitute their valuation systems. Such discourses about academia often entail researchers’ assessment of which academic practices are more highly valued than others and their beliefs about what institutions value. For instance, publishing in high-impact factor journals is commonly perceived as an academic practice that is highly valued. One wonders if these valuation discourses could differ across career stages. Hence it is worth comparing the case studies of an ECR and a veteran academic with a focus on disciplinary positioning.

Disciplines and academic identities

Disciplinary positioning is understood as a discursive process that could be examined through how researchers self-position and employ certain disciplinary labels. Disciplines are seen as a product of institutional organization and so disciplinary classification is not cast in stone but is mostly socially constituted (Becher and Trowler, 2001, p. 59). While disciplines are in part identified by the existence of relevant departments, it does not follow that every department represents a discipline (Becher and Trowler, 2001, p. 41). This was indeed true when I found out that for some respondents, they self-identify with a discipline that may differ from the perceived disciplinary affiliation associated with their institutional department, partly because in their institution, there was no department for their self-identified discipline. Presumably when it was not viable for a university to establish a solely linguistics department, it may cluster several related fields and disciplines together to form hybrid configurations called “School of Languages and Communication” for instance.

Given that higher education institutions have become more discipline-oriented since the emergence of the modern research university which is structured around separate disciplines (Billig, 2013, p. 14), the notion of a disciplinary community is especially important in how researchers position themselves and communicate their research. Abbott argued that disciplines provide academics with a general conception of intellectual existence, a conception of the proper units of knowledge (2001, p. 130) and “a core element of the identity of most intellectuals in modern America” (Abbott, 2002, p. 210). Studies investigating disciplines and academic practices believe that disciplinary communities impact on academic identities and researchers’ beliefs about their work practices (Becher and Trowler, 2001; Hyland, 2012; Myers, 1990). Therefore, academic practices, ways of producing research and presenting oneself as a researcher could arguably be strongly influenced by one’s disciplinary affiliation. A logical consequence of the formation of disciplinary communities would be the need for novice researchers to try to gain membership and be socialized into a particular disciplinary community (Abbott, 2001; Becher and Trowler, 2001; Billig, 2013; Gerholm, 1990). The need to belong to a discipline or having a disciplinary affiliation helps shape the researcher’s identity. It also enables other researchers to make sense of the researcher and to see her/his research in light of the larger discipline.

Hence, what are the implications for my two case studies who resisted belonging to just one discipline (i.e. applied linguistics)? Perhaps, it is worth considering briefly how self-identified applied linguists perceive the field. The field of applied linguistics traditionally began as one which was primarily concerned about English language teaching (Davies, 2007). Over the years, the field has grown to include research that adopt a language perspective in studying and finding solutions to real world problems (Davies, 2007; Hellermann, 2015) and applied linguists are seen as mediating between theory and practitioners’ concerns that involve language use, and especially in the case of language learning (Ellis, 2016; Widdowson, 2000). Some scholars held the stance that the field has become a disparate one with almost irreconcilable interests (Cook, 2015). Being a relatively young field and less established than linguistics, the demarcations of sub-fields within applied linguistics remain relatively fuzzy.

The respondents in this paper were more inclined to describe their work as having shifted disciplines or traversing different fields and disciplines than to use the term ‘interdisciplinary’ to describe their research during the interviews. Still, it warrants a brief consideration of the literature about interdisciplinary research. Literature about interdisciplinary research continue to raise questions about how it can be defined or measured (Huutoniemi et al., 2010; Klein, 2008) and there remain gaps in our understanding about how engaging in interdisciplinary research can impact on academic careers and identities. Recent developments in higher education seem to favour interdisciplinary research as seen in the presence of specialized funding (Rylance, 2015; Van Noorden, 2015), proposals to accord recognition to it in the REF 2021 (UKRI, 2020); and growing support and efforts in universities to foster interdisciplinary collaboration (Brown et al., 2015; Choi and Richards, 2017b). But there remains scepticism as to whether interdisciplinary research is put at a disadvantage in terms of academic citations and research evaluation (Rafols et al., 2012).

The younger respondent in this paper, Alf, began his academic career in the 2010s while David, a Professor Emeritus, began his career in the 1980s. Understandably, attitudes and perceptions of interdisciplinary research have changed over the decades. Despite so, this paper argues that researchers who self-identify as working in more than a single discipline, continue to struggle. In fact, this paper contributes to our understanding of how academics, who self-identify as working at less well-defined fields or at the intersections of disciplines, position themselves.

With these in view, one wonders: How would academics position themselves if they perceive themselves as working in more than one field or discipline? How do they negotiate with institutionally imposed disciplinary demarcations in enacting their disciplinary positions? How does their positioning belie their beliefs and valuation of what it means to be an academic? And how could this paper attempt to examine their disciplinary positioning struggles? The methodological approach underpinning this paper is elaborated in the following section.

Talk constitutes social action

This paper’s approach is guided by notions in interactional linguistics and pragmatics, where talk is understood to constitute social action. Hence utterances are discursive acts that “do” something such as positioning the speaker in certain ways. During the interview, interlocutors tap into shared (sometimes unshared) tacit knowledge about academia in order to make sense of these struggles. This tacit knowledge is examined as discourses about academia. Usually implicit and unspoken, they may be implied or alluded to and are usually made more explicit during a negotiation of understanding especially when interview participants do not share the same tacit knowledge. Another question invariably follows: What are the discourses that academics draw upon to speak about themselves as researchers and to understand the academic world?

In the process of constructing and accounting for these struggles, academics position themselves in certain ways. Davies and Harré defined positioning as discursive practices which “constitute the speakers and hearers in certain ways and yet at the same time is a resource through which speakers and hearers can negotiate new positions” (1990, p. 62). Positioning in academia is understood as a discursive practice that academic researchers engage in continuously to “negotiate academic subject positions” by applying social categories to others and themselves (Angermuller, 2017, p. 967). In order to make sense of others and enable others to make sense of us as researchers, we employ academic categories and this, in turn, evokes certain ideas and beliefs that people have about which academic categories and practices are valued. This is done discursively through the co-construction of positions and meaning by the interviewer and respondent in the qualitative interview. Interview participants draw upon tacit and shared, or sometimes, unshared knowledge about academia.

Valuation discourses behind disciplinary positioning struggles

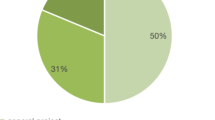

Figure 1 proposes a way of conceptualizing how disciplinary positioning struggles are enacted and talked into ‘being’ through utterances and discursive acts while at the same time, valuation discourses about academia are produced to account for these struggles. The interviewer and respondent position each other as they negotiate understanding and make sense of each other’s stances through turn-by-turn talk. Respondents position themselves vis-à-vis others or vice versa, including sometimes the interviewer through a series of discursive acts, such as justifying, accounting, clarifying, and many others. These discursive acts are fulfilled by a range of pragmatic resources, which includes voicing and humour.

Valuation discourses about academia are construed as shaping how disciplinary positioning struggles are understood and at the same time perpetuated by their construction through talk. Thus, in a continuous and never ending cycle, discourses are produced and reproduced through discursive and social practices.

Data and methodology

Data

Two case studies were selected from a pool of thirty qualitative interviews with academic researchers working in linguistics and language-related fields at seven different universities in the UK. These interviews were conducted for my PhD study, which examined the positioning practices of academic researchers in the UK. The interviews were conducted over a year from January 2016 to January 2017. Respondents had to be working in the fields of applied linguistics and linguistics as full-time academic and research staff in UK universities at the time of interview. For practical reasons, I approached relevant departments in three UK universities. However not everyone in the selected departments agreed to an interview. Out of 30 respondents, 24 came from the three universities, which I had approached initially and the rest came from other universities. Eight were academics that were recommended to me by colleagues and five were academics or PhD students whom I knew.

In a semi-structured interview, respondents were asked about their biographical backgrounds, research, academic activities and publications. The interviews typically ran from 30 min to around an hour. These interviews were audio-recorded with the participants’ consent. They were transcribed for some features of speech with transcribing conventions adapted from Jefferson’s style for conversation analysis (see Box 1). The transcripts were then coded using MaxQDA, a qualitative data analysis software. I found that the codes ‘resistance’ and ‘struggles’ came up frequently therefore academic struggles became the focus of my thesis. All data collected were anonymized and pseudonyms were used for respondents’ names and institutional affiliations in this paper.

Of the 30 interviews, ‘disciplines’ was identified as a recurrent theme that respondents discussed at length. A number of them talked about their difficulties with positioning their research in a certain field or discipline and being recognized for it. I have made observations about such disciplinary positioning struggles as a particularly salient issue among ECRs in another paper (Hah, 2019). While it can be expected that one of the struggles that some ECRs face was to establish their niche and be recognized for it, there are others who work at the intersections of fields and disciplines. They too face struggles with positioning their research in ways that they could gain recognition for. The selection of these two case studies for this paper was an attempt to probe disciplinary positioning in cases where academics want to be seen as working in more than one discipline. I also wanted to show how such discipline-related struggles were perceived by more senior academics and how they recounted these experiences faced at earlier stages of their career.

The two respondents cited in this paper come from two different universities, which would be called Eastern and Lakeside in this paper, in the UK. At the time of interview, they came from linguistics-related departments. They have been selected because they positioned themselves as academics who eschewed limitations imposed on their autonomy or creativity by perceived disciplinary boundaries or “mavericks” (in David’s words). They also came from two ends of the spectrum in a typical academic career trajectory. Alf had started his first academic job as LecturerFootnote 2 after obtaining his PhD, while David was a Professor Emeritus. They did their PhDs in different fields but have ended up in applied linguistics departments at the time of the interview. By examining how they constructed their disciplinary positioning struggles (in the past or present), I show how they evoked valuation discourses and positioned themselves as “maverick” academics.

Methodology

The role of the interviewer in qualitative interviews

The qualitative interview is understood as a speech event where meaning is co-constructed and not just a research instrument to tap into respondents’ minds (Lampropoulou and Myers, 2012; Mann, 2016). Hence the interview is seen as a co-constructed speech event where the interviewer has a role in steering, facilitating and influencing the outcomes of the interview (Kvale and Brinkmann, 2015; Roulston, 2014; Tanggaard, 2007). Interview accounts are understood as not just respondents’ reports of their experiences in their academic work life but also “rhetorical enactments that construct the events that they report” (Atkinson and Sampson, 2018, p. 10). Interview participants make sense of these experiences and events by drawing on the “collective tropes that are shared among a given speech community” (Atkinson and Sampson, 2018, p. 10). These collective tropes could be understood as knowledge that people draw upon to make sense of their social realities. When more and more people draw upon certain discourses to make sense of their social worlds, they become “distinctive ways” of thinking, understanding, interacting and valuing so as to “enact specific socially recognizable identities engaged in specific socially recognizable activities” (Gee, 2015, p. 171). In other words, these are discourses that people draw upon to make sense of their experiences. Hence, academic researchers are recognized as researchers by the discourses they engaged in, in terms of valuing and thinking about academic practices. Disciplinary positioning is one dimension of how they convey themselves as researchers.

Analysis

The following excerpts have been selected with the intention to illustrate struggles related with disciplinary positioning. I attempt to show how these struggles are manifested in academics at earlier and later stages of the academic career. In order to do this, I selected excerpts from interviews with Alf, an ECRFootnote 3, and David, a Professor Emeritus. Through the construction and accounting for their struggles, these researchers positioned themselves in certain ways (i.e. perform various academic identities) and evoked certain valuation discourses about academic practices. This is done by a close analysis of the interviews and their CVs.

Disciplinary positioning struggles at the early career stage

At the onset of an academic career, ECRs often struggle with positioning themselves and their research in order to be recognized as knowledge experts in their niche within a particular discipline (Hah, 2019) and to obtain ‘legitimacy’ as an academic (Archer, 2008; Sutherland, 2017). For many ECRs, the true test of being recognized for one’s expertise lies in obtaining the first academic position. In Alf’s case, his recount of a missed job opportunity illustrated how he positioned himself as belonging to a certain disciplinary community but was positioned otherwise by the institution.

Alf, ECR, Lecturer, Eastern University

Alf had applied for a position at what he described as an “old school linguistics department” and they had perceived him as not enough of a linguist at RizonaFootnote 4. Alf constructed his account like a story and began by setting the scene with details about the “kind of old school linguistics department” as compared to his current department which he described as “more open minded”.

Excerpt 1 Alf_20161201_#00:15:51-6#

1 | Alf: | There was this time:: when I was at: I applied for linguistics department at the University of Rizona. Er:m an::d it’s a very kind of old school linguistics department, erm this one is a little bit more open minded, and they were very like (.) ((tongue click)) traditional linguistics. |

5 | Er:m an::d I:: I got erm shortlisted for the job, erm An::d the::n there was a little bit of concern well it was the feeling I got from talking to people there and actually that’s the feedback I got from them, that I had a degree in er cognitive science, that I was not enough of a linguist. |

In a series of self-initiated repairs, Alf formulated the reason for being rejected. Just as “participants’ conversational versions of events (memories, descriptions, formulations) are constructed to do communicative, interactional work” (Edwards and Potter, 1992, p. 16), Alf was not merely recounting an experience but was, in fact, evaluating Rizona as a traditional linguistics department which connoted a lower tolerance for interdisciplinary research (later excerpt 3).

In seeking to understand why Alf could be seen as not enough of a linguist, I probed his educational background. Embedded in my question was the assumption that one’s disciplinary label needed to be supported by one’s educational credentials (10). Although Alf was quick to justify his credentials, he did not challenge this assumption and in fact, reinforced it.

Excerpt 2 Alf_20161201_#00:15:51-6# (continued)

10 | I: | Your PhD was in cognitive science? |

Alf: | My PhD was in cognitive science= | |

I: | = Oh [right. | |

Alf: | [Yah right. But my Ma-Masters was [in linguistics | |

I: | [yah right | |

15 | Alf: | And my undergrad was essentially in linguistics. |

I: | Yah right |

Alf’s admission that his PhD was in cognitive science was marked by my ‘Oh’-prefaced response (12) as new information (Heritage, 1998, 2018). Overlapping my turn, Alf quickly justified that his Masters degree was in linguistics (13) and a similar, albeit hedged, claim about his undergraduate degree (15). This exchange seemed to mirror Alf’s struggle to prove he was ‘linguist enough’ for Rizona. The assumptions inherent in my question could arguably be unwarranted. Given how diverse and heterogeneous researchers’ beliefs are about what constitutes the field of applied linguistics (Cook, 2015; Hellermann, 2015; Shuy, 2015), demarcating sub-fields within applied linguistics could be complicated. In general, the demarcation of fields and disciplines is further complicated by how funding agencies are becoming more encouraging of interdisciplinary research (Choi and Richards, 2017a) which provides impetus for the birth of new permutations and coupling of fields and disciplines. The trend towards interdisciplinarity implies more varied disciplinary categories that researchers could mobilize and thus makes it more difficult to judge a researcher’s disciplinary positioning based solely on her/his academic qualifications.

In further efforts to claim his expertise as a linguist, Alf declared that he had published in linguistics journals (Excerpt 3) and this evokes another ‘soft’ category (Angermuller, 2017) in evaluating a researcher’s disciplinary positioning according to where s/he had published. Getting published in peer-reviewed journals could logically equate to ratification by the disciplinary community and hence membership of the discipline, since journals are often seen as gatekeepers of a discipline. Hence a closer look at Alf’s publications is warranted. In his CV, Alf listed 26 journal papers and a number of proceedings, book chapters and more publications. If we were to focus on journal papers, it could be seen that 11 out of 26 papers were published in linguistics-related journalsFootnote 5 while others had topics related to language but were more inclined towards cognitive science.

Excerpt 3 Alf_20161201_#00:16:47-3#

1 | Alf: | So erm I have published in linguistics journals and so on. Erm |

I: | uh huh | |

Alf: | But then, (.) they: were like kind of like (.) Yah er:m but (.) Er:: Is he really a linguist enough? And I really felt that my: (.) the fact | |

5 | that I did so many different things and I didn’t really have a well defined research programme. I mean the-er >as I mentioned to you< I’m kind of all over the place. That fact really backfired with that particular position, because they really didn’t, they wanted somebody who’s like more specialized↑ and focuses really only | |

10 | on language. But at the end I was kind of happy that I didn’t get the job, because if they don’t like that, then I don’t wanna be there. I wanna be at a place where it’s ok with me to be doing (.) the occasional (.) non linguistics thing or something different so (.) erm- |

Alf seemed to be voicing Rizona’s evaluation of his linguistic credentials in: “Yah er:m but (.) Er:: Is he really a linguist enough?” (Excerpt 3: 3−4). Voicing or speaking in a different voice enables speakers to evoke other voices besides the speaker’s own voice and enables them to speak from multiple standpoints (Couper-Kuhlen, 1999; Goffman, 1981; Günthner, 1999; Holt, 2017). Voicing served as pragmatic recourse for speakers to fulfil their communicative goals such as indirect evaluation (Vološinov, 1973) or rapport-building with interlocutors. It could also take the form of reported speech, where it is used to re-enact an interaction and also to “enable the speaker to simultaneously convey his or her attitude towards the reported utterance” (Holt and Clift, 2006, p. 07). In this case, Alf was possibly re-enacting Rizona’s doubtful reaction.

In accounting for this rejection, Alf had positioned Rizona as a department which seemed rigid in the sense that they wanted someone focusing “really only on language” and less accepting of a diverse or less than “well defined research programme”. An unclearly defined research programme translated to an unclear disciplinary positioning. Alf ended his recount with a ‘happy’ ending insofar that he was “kind of happy” that he did not end up at Rizona. The prosodic emphasis in his assertion conveyed that the rejection was mutual on some level: “…if they don’t like that, then I don’t wanna be there” (11). If Rizona did not like his diverse research portfolio, he did not want to join them either. He also made it clear that he preferred to be in a more open-minded environment which allowed for more freedom in pursuing his research interests, including non-linguistics ones (Excerpt 3: 10–14).

As seen in Alf’s case, the struggles to define one’s disciplinary label are to do with how one is perceived by institutions, in this case Rizona had deemed him as not qualified enough as a linguist. In Alf’s account, he referred to the institution’s valuation of his academic profile as being at odds with his own valuation. There seemed to be an implicit valuation of the institutionally desired profile of a linguist to be one who has had formal academic qualifications in linguistics from Bachelors to PhD; and to have done research and published in recognizably linguistics areas. Alf’s justification seemed to construct his PhD in cognitive science and his diverse research interests as the reasons for an unclear disciplinary positioning, thereby leading to the missed job opportunity. Also embedded in Alf’s accounting for his struggle was his positioning of himself as a researcher who desires versatility in his disciplinary positioning and not to be limited to the one ascribed by his departmental affiliation. Consequently, he evoked valuation beliefs about the kinds of research environments that are deemed more desirable for researchers like himself—i.e. one that allows for researchers to pursue a more diverse research programme and essentially one that provides academic autonomy.

In an earlier part of the interview, I had asked Alf about his disciplinary affiliation. He had reported feeling “torn between calling [himself] a cognitive scientist and a linguist” (#00:09:55-7#). This conversation had led to Alf expressing his stance against disciplinary labels and how they are socially constructed (Excerpt 4).

Excerpt 4 Alf_20161201_#00:12:15-2#

1 | Alf: | I mean I think like mostly disciplines are administrative divisions that the university comes up with? Er::m |

When probed further on why he did not like labels, Alf gave the following explanation (Excerpt 5).

Excerpt 5 Alf_20161201_#00:13:17-3#

1 | Alf: | Yah, labels are useful shorthands (.) a lot of the time. So they kind of like (.) So: er::m If I call myself a linguist yah? Then: people have certain types of- Then they know Ok this person I-knows: what a morpheme is. Because I don’t have to explain to this person so in that sense they are |

5 | useful. Because when-when I know Ok this person is a linguist, then I know er:: what we can take for common ground, like what this person would understand, Er:m if she says she’s a neuroscientist then I know (.) | |

OK she probably knows about the brain. | ||

I: | Mm | |

10 | Alf: | Er:m in that sense labels are useful but I think (.) Erm if we:: I think a lot of times, people are kind of like thinking too much in the box (.) because I think a lot of problems in linguistics and in other fields, can only be tackled |

(.) erm if we take inspiration from other fields and talk to people from other fields. | ||

15 | I: | Other fields? |

Alf: | Yah other fields yah. Yah I mean ther-there’s the fields again like so:: ((laughs)) | |

I: | ((laughs)) | |

Alf: | I guess. Yah I mean thes-these fields do exist. Er:: Maybe? Erm but I | |

20 | guess we have to: er: (.) | |

I: | Yes | |

Alf: | In my mind at least I think we should be as open as possible. SO that’s | |

25 | why I don’t really like the labels too much. |

Through a series of voicing aloud (Excerpt 5: 3, 5, 8), Alf contended the usefulness of disciplinary labels as ways of making sense of academic peers and knowing “what we can take for common ground” (6–8). Herein lies the double-edged sword that disciplinary labels are. As aforementioned, disciplinary labels enable academic researchers to be made sense of and to be positioned by others within and beyond the academic profession. At the same time, academics could be bound or constrained by the assumptions, expectations and valuation discourses that others may have of someone that is positioned in one particular field. For instance, belonging to a certain disciplinary community could imply a certain degree of imbibing and participating in a scientific culture (Pinch, 1990). To Alf, claiming an affiliation with a disciplinary community brings with it a risk of “thinking in the box” and he advocated the need for scientists to “talk to people from other fields” (10–14). There was a moment of shared laughter (15–20) as Alf realized that he had contradicted his previous assertion to disregard fields and disciplines as mere institutional divisions (in Excerpt 4). Excerpts 4 and 5 could be interpreted as Alf challenging the need for disciplinary labels albeit his rumination that they could be useful to some extent.

Since Alf concluded that he was happy in his current department, his recount of a missed job opportunity might not seem like a struggle to some. Yet from Alf’s perspective, he felt that his positioning of his research and himself in more than one discipline had ‘backfired’ on him in this particular job-seeking context (Excerpt 3). This bore testament to the kinds of disciplinary positioning struggles that particularly affect ECRs. There are many other ECRs who enacted their struggles with positioning and justifying their research in other ways and most of these have to do with seeking employment, funding and getting published (Hah, 2019). One wonders if such struggles were unique only to ECRs and how more veteran academics would have grappled with questions of disciplinary positioning in the earlier parts of their career. Thus, I examined the case of a veteran academic researcher (David) in the following section.

More experienced academics and disciplinary positioning

Like Alf, David, a Professor Emeritus, was an academic researcher who placed much emphasis on following his heart in forging his research programme. In the following excerpts, he related an early decision in his academic career to follow his passion instead of staying in the discipline he did his doctorate in. In response to the first question in the interview, David set himself apart as someone who resisted against being seen as belonging to one discipline.

David, Professor Emeritus, Lakeside University

Excerpt 6 David_20160204_#00:03:24-5#

1 | I: | How come you have become who you are? |

David: | Right but er it’s various (.) various factors some of which are accidental. (.) I’ve always felt I had several persona: in the research (.) context. And I don’t commit to any particula-I don’t feel like I only have one research | |

5 | identity (.) so: er::m I don’t know how-part of the difficulty of answering this question because I don’t know how I’m seen by (.) other groups I’d rather suspect that (.) different things that I’ve published (.) speak to different people. They have different sets of readers (.) and that is because I’ve changed directions many times (.) and been interested in many different | |

10 | things. An::d I’ve never felt totally (.) inside one particular discipline. In fact I don’t very much (.) like (.) the word (.) discipline (.) cuz I do not like to be disciplined by anybody. |

David positioned himself as a researcher who had several “persona” or research identities because he had “changed directions many times and been interested in many different things” (8–10). He did not like to be seen as being in only one particular discipline and seemed to refer to the idea that being in a discipline meant having to submit to the rules that apply to belonging to that particular discipline (10–12). This seemed to evoke the idea of disciplinary socialization where more junior academics learnt to write and engage in disciplinary practices in order to signal membership of that “disciplinary tribe” (Becher and Trowler, 2001; Billig, 2013). Akin to Alf’s resistance towards having to ‘think within a disciplinary box’ (Excerpt 5), David was referring to similar discourses about the impositions of a disciplinary culture.

While David did his PhD in European Studies, he moved on to linguistics and discourse analysis early on in his career. David accounted for his shift by comparing two of the former heads of department in the department he taught at in Excerpts 7 and 8. Similar to Alf’s comparison of Rizona and the department which finally hired him, David’s comparison of his superiors evoked his valuation of what he prized in a ‘head of department’ and what being an academic meant to him.

Excerpt 7 David_20160204_#00:05:44-4#

1 | David: | So I’ve moved around (.) in many ways. (.) I made- I made a career?- I made a living (.) out of teaching Language M (.) essentially and my-my PhD was on M literature er:m |

I: | [Wow | |

5 | David: | [So it was a detailed linguistic analysis (.) as well as historical and |

literature (.) literary context. And I taught, my main-main job in my career (.) has been here, in XYZ department. […] My head of department at that time was very open-minded, erm encouraged any kind of intellectual enquiry. And I fe:lt here in those days | ||

10 | that you felt-you thought of yourself as an (.) intellectual perhaps in the French sense (.) of an intellectual (.) and not as an academic (.) committed to a particular discipline (.) with particular goals. So (.) er:m- | |

I: | What’s an intellectual in the French (.) sense? [((laughs))] | |

15 | David: | [Well it’s it’s ((laughs))] let- well the French intellectual in France (.) traditionally would: be somebody who has particular status in French society for one thing. As somebody who is a thinker, in-on anything (.) with a philosophical (.) tendency |

I: | Alright. |

David’s description of his former head of department as someone who was very “open-minded” and encouraging of any kind of “intellectual enquiry” (8–9) needs to be seen in contrast with his later head of department in Excerpt 8. There is clearly a comparison made between two of his former bosses with the former characterized as more allowing of academic autonomy and the latter as more imposing (Excerpt 8). The co-construction with the interviewer about how he perceived himself as a French intellectual further positioned him as an academic researcher who did not like to be restricted (Excerpt 7: 10–18). Interestingly, David distinguished between “intellectual” and “academic” whom he understood as “someone who is “committed to a particular discipline with particular goals”; and his making this distinction revealed his valuing of freedom in enquiry as integral to an academic’s identity.

In Excerpt 8, David spoke about how his desire for academic autonomy was threatened by the RAEFootnote 6 (1–5). At that time, from David’s perspective, his kind of research in linguistics was “not considered under the RAE or REF panels” and this implied that it was not considered by his superiors to contribute value to an RAE assessment of the department (11–15).

Excerpt 8 David_20160204_#00:08:30-8#

1 | David: | Er:m: (.) SO (.) I was already interested in linguistics when I came here (.) and: because the atmosphere was so relaxed erm from a disciplinary point of view. I just continued doing linguistics and concentrating on it more and more no problems. However when it came to the the 1980s an:d it came to |

5 | what was known as the RAE, the research assessment exercise, | |

I: | Yes. | |

David: | Or what is now known as the REF. | |

I: | Yes that’s right. | |

David: | The disciplines became much tighter. | |

10 | I: | Ok. |

David: | And so: linguistics (.) was not considered under the RAE or REF panels. | |

I: | Ok. | |

David: | So I was told that actually by my erm erm my later head of department that I should not really continue er:m researching in (.) in | |

15 | er: (.) linguistics. Really I should be doing work in M literature which I lost interest in. I basically lost interest in it and wasn’t researching. You see on my publications list, I would have separated out: the literary (.) publications. | |

I: | Mmhm | |

20 | David: | SO ANYWAY tha-that’s that’s th- (.) this is why I’ve different identities in terms of seeing myself as a researcher. |

In Excerpt 8, David referred to his later head of department with his use of reported speech, which is a form of voicing: “So I was told that actually by my erm erm my later head of department that I should not really continue er:m researching in (.) in er: (.) linguistics. Really I should be doing work in (European Language M) literature which I lost interest in”. The phrase “I was told”, in the passive voice, implied an imposition made by his former department head on the kinds of research that he and his colleagues were allowed to do at that time. There is hence a certain evaluative undertone in David’s voicing here.

A closer look at David’s career appointments and publications list confirmed that he had made a gradual shift from literary studies to linguistics. For the first 23 years of his career from obtaining his PhD, David was in a literary department. He made the switch, first, to a language and communication department before joining a linguistics department; and remained there till he retired as Professor Emeritus. While lecturing at the literary department, he was publishing about language, linguistics and discourse concurrently with literary studies. During his time at the literary department, David published 10 literary publications and 30 linguistics ones. He had indeed separated his publications related with literary studies (11) and these were less extensive than those he had published on linguistics and discourse (71).

David’s insistence on not being constrained by a discipline continued in his following observations about researchers becoming too conformist if they adhered too much to a disciplinary identity in excerpts 9 and 10. While David valued non-conformity (Excerpt 9: 1–4), at the same time, he recognized that it could come with drawbacks (4–6). The laughter that followed his utterance “there’s… not much money in it and not much prestige” indicated it as a non-serious utterance (Holt, 2013; Shaw et al., 2013), which was recognized by the interviewer, hence the laughter in her response.

Excerpt 9 David_20160204_#00:25:39-4#

1 | David: | Whereas I’m (.) I’m much more impressed by thinkers and people generally who ar- (.) who have creative ideas (.) new ideas different ideas. |

I: | Yah | |

David: | That’s what has always impressed me. It’s not- it’s probably not very good | |

5 | because there’s not much (.) not much money in it and not much prestige. ((laughs)) | |

I: | ((laughs)) I see I see. […] |

Irony is almost always an indicator of polyphony (Angermuller, 2014) and David did not really mean what he was saying here. In fact, this could be understood as self-deprecating humour and an indirect reference to his own trajectory, as David went on to claim to be a maverick in Excerpt 10.

Excerpt 10 David_20160204_#00:27:20-7#

1 | David: | Yes. I mean and I would justify it by saying (.) that there’s always a danger with being too conformist, because (.) Especially in the social sciences and and the humanities. there’s a- (.) You NEED to preserve originality and creativity and (.) you know th- the awkward (.) and the different. |

5 | I: | Mm |

David: | (1.0) are the people who are th-slightly >you know this word maverick?< (xxx) in Jewish? | |

I: | Maverick? | |

David: | Maverick. | |

10 | I: | Yes yes [I do] |

David: | [Maverick.] I think I’m prob-I see myself as a bit of a maverick. |

Excerpt 10 bore testament to David’s stance against conformity in thought and he positioned himself as a “maverick”. While the construction of a disciplinary positioning struggle is not immediately seen in David’s interview, it was indirectly referred to in Excerpts 6–8, as something that he had faced early on in his career, not without difficulties. But the positioning he had acquired from the set of decisions he made back then, could be seen in his accounting and justification for why he had resolutely adopted a “maverick” persona. David’s valuation discourses were embedded in larger discourses about social sciences and the humanities as “creative” disciplines where originality and non-conformist attitudes are encouraged. David positioned these non-conformist “thinkers” as the ones who could be “awkward” and “different” from the mainstream, and that non-conformity could come at a cost (money, prestige). There is an implication that struggles could arise from incongruence between the individual’s valuation of academic practices and the views of the mainstream. Like Alf, David valued autonomy for researchers to pursue their interests, without conforming to disciplinary boundaries.

Discussion

Alf and David had constructed struggles with defining one’s disciplinary label and not wanting to be compartmentalized in a single discipline. On the one hand, both academics wanted the freedom to pursue their research interests without adhering to any particular disciplinary or institutional obligations. On the other, there is a cost to not having a well-defined disciplinary positioning, as seen in Alf’s missed job opportunity and David’s reporting that it came with less prestige. The preceding analysis has illustrated how these two academics constructed their struggles through discursive acts and in the process, evoked valuation discourses about disciplinary positioning. Extending from the idea that discourses are produced and reproduced through talk in Fig. 1, I show how valuation discourses about disciplines are evoked in the two case studies (Fig. 2).

Embedded in their comparison of institutions and superiors, there is implicit evaluation when they accounted for their struggles. Alf’s voicing and comparison of Rizona and Eastern bore an evaluative overtone of the kind of research environment that he valued. Similarly, David’s use of reported speech constructed a juxtaposition between two of his former heads of department—one as more generous with allowing freedom of academic enquiry while the other less so, to the extent that resulted in David’s move to another institution. Voicing could be seen as a pragmatic resource that speakers employ to indirectly compare and evaluate, by evoking other voices (besides their own) and discourses. Through voicing, both Alf and David positioned themselves as resisting against research environments or institutions that imposed constraints on academic freedom.

In David’s case, we see his use of ironic or self-deprecating humour in what he conveyed as a lower regard mainstream academia have for “thinkers” and “mavericks” like himself. In this way, he positioned himself as differing from the academic majority, whom he described as academics who toed the disciplinary boundaries, while he was a “French intellectual” who pursued any research directions that he liked. These are labels that speakers create and ascribe to themselves and they serve a communicative role in positioning the speaker and others.

Both Alf and David made use of labels to position themselves as academic researchers. Alf ruminated about his dilemma between calling himself a linguist or a cognitive scientist and resisted the need to be categorized by these labels. Yet he evoked certain valuation discourses when he labelled Rizona as “old school” unlike the more “open-minded” department at Eastern, which hired him. He also described himself as being positioned as “not being linguist enough” because he did the “occasional non linguistics thing”. David used labels like “French intellectual” and “maverick” to position himself as a “thinker” who advocated creativity; unlike an academic who typically had to conform to disciplinary norms.

All these discursive acts evoked discourses of how academics need to conform to certain disciplinary norms and implicit rules (or being “disciplined”) to some extent. Alf and David’s struggles were constructed from the incongruence between their valuing of academic autonomy over what they positioned as the mainstream or institutional preference for academics to show a clear disciplinary affiliation. Consequently, they challenged disciplinary labels because they viewed disciplinary labels as imposed by institutions.

Limitations of paper and future directions

While the analysis and selected excerpts illustrated the kinds of struggles faced by academics at two key stages in a typical academic career, they may not be taken to be representative of all academics at that particular career stage. It must also be noted that not all academic researchers face the same kinds of struggles at these stages of their career as delineated. In other words, not all ECRs position themselves in the same way as Alf did. There are also researchers who do not claim to traverse disciplinary boundaries as much as David. Given that the data sample is rather small, more interviews would be needed before broader claims could be made about how academic researchers embody the desire for academic freedom and perform other aspects of their professional identity.

Conclusion

Valuation lies at the heart of many kinds of discourses about academia. Academic evaluation takes many forms as can be seen in the myriad of implicit valuation discourses relating to disciplinary positioning. Researchers constantly evaluate which kinds of research outcomes are more worthwhile, the kind of researcher they want to be perceived as (or positioned as), and the attributes of research environments that appeal to them. Such valuation discourses are embedded in tacit knowledge which researchers draw upon to make sense of their social realities and to account for their struggles. Angermuller provided a discursive perspective on how academic careers are organized by categories which define “who academics are (subjectivation) and what they are worth (valuation)”. This paper takes a closer look at how academic categories such as disciplinary labels are mobilized. It contributes a discursive exploration of how academics negotiated their disciplinary positions using categories and evoking valuation discourses. To some extent, researchers’ valuation systems could be influenced by institutional valuation, especially REF-related requirements and the preferences of funding councils. Valuation is constantly negotiated depending on who the stakeholders and what they value under a certain set of circumstances. Interdisciplinary research, while valued at one institution, might not be valued at another. Some academic researchers find that they need to have a research programme that can be recognized by institutional recruiting panels as falling within a discipline in order to obtain a job. Others benefit from having a more diverse research programme that traverses disciplines when they apply to interdisciplinary departments or research projects.

It seems to be a perennial conundrum for all academics to have to negotiate between being recognized for having expertise in a certain field of knowledge—often under the precipices of a discipline—and at the same time, be able to differentiate oneself sufficiently from other academics to be known for unique expertise or for claiming a particular niche area of knowledge. In an academic world increasingly drawn to ‘academic celebrity’ (Angermuller and Hamann, 2019), reputation seemed almost to precede the other aspects of an academic researcher’s work such as teaching, service and administration.

One wonders too if valuation discourses would differ among academics who work in teaching-oriented vis-à-vis research-oriented institutions? Would academics who have spent more of their career in teaching positions display stronger adherence to a discipline? Conversely, would academics who have experienced academic employment mostly in research positions display a more fluid trajectory between disciplines? These could be worthwhile questions in future studies.

Data availability

The datasets analysed in this paper are not publicly available, as participants in the study have been promised confidentiality; but are available (in anonymised form) from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

The Research Excellence Framework (REF), formerly known as the Research Assessment Exercise (RAE), is the system for assessing the quality of research in UK higher education institutions.

At the time of the interview, Alf had just joined the department for around 2 months.

Most of the early career researchers (ECRs) in my data set had been in full-time academic employment for less than one or two years. They were mostly postdoctoral fellows, teaching fellows or lecturers.

Pseudonym for institution that Alf applied to.

Examples of linguistics-related journals which Alf published in were: Journal of Language Evolution, Journal of Pragmatics, Journal of Phonetics and more.

Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) was the predecessor of the REF.

References

Abbott A (2001) Chaos of disciplines. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Abbott A (2002) The disciplines and the future. In: Brint S (ed) The future of the city of intellect: the changing American University. Stanford University Press, pp. 204–230

Angermuller J (2013) How to become an academic philosopher: academic discourse as a multileveled positioning practice. Sociol Hist (2), 263–289

Angermuller J (2014) Poststructuralist discourse analysis: subjectivity in enunciative pragmatics. Palgrave Macmillan

Angermuller J (2017) Academic careers and the valuation of academics. A discursive perspective on status categories and academic salaries in France as compared to the US, Germany and Great Britain. High Educ 73(6):963–980

Angermuller J, Hamann J (2019) The celebrity logics of the academic field- The unequal distribution of citation visibility of Applied Linguistics professors in Germany, France, and the United Kingdom. Z Diskursforschung 1:77–93

Archer L (2008) Younger academics’ constructions of ‘authenticity’, ‘success’ and professional identity. Stud High Educ 33(4):385–403. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070802211729

Atkinson P, Sampson C (2018) Narrative stability in interview accounts. Int J Soc Res Methodol 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1492365

Becher T, Trowler P (2001) Academic tribes and territories: intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines. The Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press, Philadelphia

Billig M (2013) Learn to write badly: how to succeed in the social sciences. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Brown R, Deletic A, Wong T (2015) Interdisciplinarity: how to catalyse collaboration. Nat N. 525(7569):315

Choi S, Richards K (2017a) The dynamics of identity struggles in interdisciplinary meetings in higher education. In: De Mieroop DV, Schnurr S (eds) Identity struggles: evidence from workplaces around the world. John Benjamins Publishing Company, vol. 69. p. 165

Choi S, Richards K (2017b) Interdisciplinary discourse—communicating across disciplines. Palgrave Macmillan

Cook G (2015) Birds out of Dinosaurs: the death and life of applied linguistics. Appl Linguist 36(4):425–433

Couper-Kuhlen E (1999) Coherent voicing: on prosody in conversational reported speech. Pragmatics and beyond new series. John Benjamins Publishing Company, pp. 11–34

Davies A (2007) Introduction to applied linguistics: from practice to theory: from practice to theory. Edinburgh University Press

Davies B, Harré R (1990) Positioning: the discursive production of selves. J Theory Soc Behav 20(1):43–63

Edwards D, Potter J (1992) Discursive psychology. Sage Publications, London

Ellis R (ed.) (2016) Becoming and being an applied linguist: the life histories of some applied linguists. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Philadelphia

Foucault M (1971) Orders of discourse. Soc Sci Inf 10(2):7–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847101000201

Gee JP (2015) Social linguistics and literacies: ideology in discourses, 5th edn. Routledge, New York

Gerholm T (1990) On tacit knowledge in academia. Eur J Educ 263–271

Goffman E (1981) Forms of talk. Blackwell, Oxford

Günthner S (1999) Polyphony and the ‘layering of voices’ in reported dialogues: an analysis of the use of prosodic devices in everyday reported speech. J Pragmat 31(5):685–708

Hah S (2018) “That’s what’s moved me to tears!”—The world of academic researchers and their struggles from a discursive perspective. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Warwick

Hah S (2019) Disciplinary positioning struggles: perspectives from early career academics. J Appl Linguist Prof Pract 12(2):144–165

Hellermann J (2015) Three contexts for my work as co-editor: introduction to the special issue. Appl Linguist 36(4):419–424

Heritage J (1998) Oh-prefaced responses to inquiry. Lang Soc 27(03):291–334

Heritage J (2018) Turn-initial particles in English: the cases of Oh and Well. In: Heritage J, Sorjonen ML (eds) Between turn and sequence—turn-initial particles across languages. John Benjamins, Amsterdam

Holt E (2013) There’s many a true word said in jest”: seriousness and nonseriousness in interaction. In: Glenn P, Holt E (eds) Studies of laughter in interaction. Bloomsbury, London, pp. 69–89

Holt E (2017) Recalling a rant: mixed form portrayed speech in interaction. Paper presented at the 15th international pragmatics conference, Belfast, UK

Holt E, Clift R (2006) Reporting talk: reported speech in interaction. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Huutoniemi K, Klein JT, Bruun H, Hukkinen J (2010) Analyzing interdisciplinarity: typology and indicators. Res Policy 39(1):79–88

Hyland K (2012) Disciplinary identities: individuality and community in academic discourse. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Hyland K, Giuliana D (eds) (2009) Academic evaluation: review genres in university settings. Palgrave Macmillan, London

Klein JT (2008) Evaluation of interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research: a literature review. Am J Prev Med 35(2):S116–S123

Kvale S, Brinkmann S (2015) InterViews: learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing, 3rd edn Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks

Lamont M (2009) How professors think: Inside the curious world of academic judgment. Harvard University Press

Lampropoulou S, Myers G (2012) Stance-taking in interviews from the Qualidata Archive. Paper presented at the Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research

Lucas L (2006) Research game in academic life. Open University Press, England

Mann S (2016) The research interview: reflective practice and reflexivity in research processes. Palgrave MacMillan, New York

Myers G (1990) Writing biology: texts in the social construction of scientific knowledge. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison

Pinch T (1990) The culture of scientists and disciplinary rhetoric. Eur J Educ 25(3): 295–304

Rafols I, Leydesdorff L, O’Hare A, Nightingale P, Stirling A (2012) How journal rankings can suppress interdisciplinary research: a comparison between innovation studies and business & management. Res Policy 41(7):1262–1282

Roulston K (2014) Interactional problems in research interviews. Qual Res 14(3):277–293

Rylance R (2015) Grant giving: global funders to focus on interdisciplinarity. Nature 525(7569):313–315

Shaw C, Hepburn A, Potter J (2013) Having the last laugh: on post-completion laughter particles. In: Glenn P, Holt E (eds) Studies of laughter in interaction. Bloomsbury, London, pp. 91–106

Shuy RW (2015) Applied linguistics past and future. Appl Linguist 36(4):434–443

Sutherland KA (2017) Constructions of success in academia: an early career perspective. Stud High Educ 42(4):743–759

Tanggaard L (2007) The research interview as discourses crossing swords the researcher and apprentice on crossing roads. Qualitative Inq 13(1):160–176

UKRI (2020) REF 2021: interdisciplinary research. Retrieved from https://www.ref.ac.uk/about/interdisciplinary-research/

Van Dijk TA (2011) Discourse, knowledge, power and politics. In: Hart C (Ed.) Critical discourse studies in context and cognition, vol. 43. John Benjamins Publishing Company, Amsterdam/ Philadelphia, pp. 27–65

Van Noorden R (2015) Interdisciplinary research by the numbers. Nature 525(7569):306–307

Vološinov VN (1973) Marxism and the philosophy of language. Translated by Ladislav Matejka and IR Titunik. Seminar Press, London

Widdowson HG (2000) Object language and the language subject: on the mediating role of applied linguistics. Annu Rev Appl Linguist 20:21–33

Acknowledgements

The writer would like to express her utmost gratitude to Prof. Johannes Angermuller for supervising the doctoral thesis that formed the basis for this paper. Any remaining errors are solely the writer’s. The research presented in this paper received funding from the European Research Council (DISCONEX project 313,172).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hah, S. Valuation discourses and disciplinary positioning struggles of academic researchers—A case study of ‘maverick’ academics. Palgrave Commun 6, 51 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0427-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-0427-2