Abstract

Research indicates that polarization has led to an increasing dispersion between moderate and more extreme voters within both parties. Intraparty polarization supposedly affects the nature of interparty competition as it creates political space for new political realignments and the rise of anti-establishment candidates. This article examines the extent and impact of intraparty polarization in Congress on US trade policy. Specifically, the article examines whether (and which) trade policy preferences are distributed within and between both parties, as well as how intraparty polarization has influenced the outcome of US trade negotiations. It is theorized that intraparty polarization causes crosscutting legislative coalitions around specific trade policies and political realignments around ideological factions, with consequences for the outcome of trade negotiations. By relying on a unique dataset of congressional letters and co-sponsorship legislation, the article first derives trade policy preferences from members of Congress and computes their ideological means. Two contemporary cases of US trade policy are examined: The Transpacific Partnership Agreement and the US–Mexico–Canada Agreement. Via a structured-focused comparison of both cases, the paper finally assesses under which combinations of preference-based and ideology-based intraparty polarization Congress manages to ratify trade agreements. Findings suggest that both parties are intrinsically polarized between free trade and fair trade preferences yet show variance in their degree of ideology-based intraparty polarization. These findings contribute to existing work on bipartisanship as well as factions in the foreign policy realm, as it shows under which circumstances legislators can build crosscutting coalitions around foreign policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intraparty polarization has become increasingly visible over the last few years in American politics. In the 2016 presidential primaries, both parties saw a record number of contenders, exposing large rifts between moderate candidates, such as Hillary Clinton or Jeb Bush, and more extreme ones, like Bernie Sanders or Donald Trump (Noel 2016; Wronski et al. 2018). Fierce intraparty competition potentially weakens the nominated presidential candidate and affects policymaking in the two-party system. Polling suggests that a substantial number of Sanders supporters in 2016, notably in key swing states, ended up either voting for Trump or did not vote at all (Kurztleben 2017). Trying to prevent a similar scenario in 2020, Joe Biden negotiated a Delegate Agreement with the Sanders campaign after Super Tuesday, which ended intraparty quarrels but eventually shifted the Biden administration’s policy agenda to the left (Ohlemacher and Barrow 2020). Intraparty contestation within the Republican party, between Trump supporters and so-called never Trumpers, had a decisive influence on the low legislative record of the 115th Congress despite unified government (Lee 2018; Saldin and Teles 2020).

New research on intraparty polarization suggests that due to decades of partisan polarization, ideologically more extreme candidates within both parties have alienated more moderate voters, contributing to a dispersion of partisans’ feelings toward their own party (Groenendyk et al., 2020). Researchers analyzing primary races have long argued that party polarization fuels intraparty competition, resulting in either a replacement of moderate politicians or an adaptation by incumbents in response to more homogenous partisan districts and intraparty pressure (Thomsen 2017; Theriault 2006). Consequently, over time, moderate Republican and Democratic voters hold less favorable views of their own respective parties compared to the opposition party, which in turn allows for new political realignments centered around anti-establishment candidates (Groenendyk et al. 2020; Abramowitz 2018).

Dynamics of intraparty polarization raise important questions for the study of interparty polarization in the foreign policy realm. Polarization has received increasing attention in recent years from scholars tracking the consequences of a decline in foreign policy bipartisanship for the maintenance of US global power (Kupchan and Trubowitz 2007; Schultz 2017; Trubowitz and Harris 2019). This debate has been accompanied by studies invested in questions related to the relative degree of domestic and foreign policy polarization in terms of ideology (Jeong and Quirk 2019), party unity (Hurst and Wroe 2016), and rates of bipartisanship (Tama 2020). This body of work suggests some variance in the extent and kind of interparty polarization across foreign policy areas, indicating that cases of cross-partisanship coalitions against the background of ideological divergence between the parties require further explanation (cf. Bryan and Tama 2020).Footnote 1

This article investigates the extent and impact of intraparty polarization in Congress on US foreign trade policy. Specifically, the article examines whether (and which) trade policy preferences are distributed within and between both parties, as well as how intraparty polarization has influenced the outcome of two specific US trade negotiations. US trade policy is particularly primed for intraparty polarization because it is commonly assumed that trade preferences, as a subset of political ideologies more generally, are shaped by factors such as the economic geography of the US or anticipated repercussions of globalization for constituents’ preferences (Milner and Tingley 2011; Rho and Tomz 2017). Scholars found evidence of higher bipartisanship rates in US trade policy compared to other foreign policy areas (Bryan and Tama 2020), further justifying the need to assess the underlying trade preferences within and between both parties (cf. Rathbun 2016).

Theoretically, and in furtherance of findings from studying intraparty polarization among voters, this article argues that intraparty polarization in Congress bears three implications for US foreign policy: First, instead of manifesting a decline in bipartisanship, intraparty polarization can produce new foreign policy coalitions around distinct policy preferences. As some studies indicate, foreign policy bipartisanship has not vanished completely but has remained operational in certain policy areas and in instances of congressional assertiveness (Bryan and Tama 2020; Tama 2020; cf. Curry and Lee 2020). Research on party fragmentation in Europe suggests that the formation of new political parties results from new social cleavages, e.g., materialists versus postmaterialists, or winners and losers of globalization (Ford and Jennings 2020). In short, it is argued here that intraparty polarization can be preference-based, foregrounding crosscutting legislative coalitions around specific trade policies.

Second, the emergence of new cleavages opens the space for new ideological gravitation centers around party factions that shift ratification pivots away from the party mean. More recent literature on foreign policy entrepreneurs has made the claim that polarization fosters political factions at the ideological extremes, which can act as free agents of policy change (Homan and Lantis 2020). As some argue, party factions can play a significant role in shaping US foreign policy by forcing the party leadership to make policy concessions in order to secure party unity (Homan and Lantis 2019; Lantis and Homan 2018; Marsh and Lantis 2016). In short, intraparty polarization can be ideology-based, foregrounding political realignments around party factions.

Third, the relationship between preference and ideology-based intraparty polarization can influence the outcome of US trade policy. An incongruence of preference and ideology-based intraparty polarization can prohibit cross-partisan coalitions for changes in US trade policy as partisan identity trumps trade preferences. In turn, a congruence of preference and ideology-based intraparty polarization can facilitate crosscutting coalitions for changes in US trade policy. Trade preferences are thereby understood as a subset of political ideologies, indicating that the ideological disposition of legislators or voters (e.g., liberal or conservative) does not necessarily translate neatly into a stable set of policy preferences mainly due to ideology’s multidimensional nature (Feldman and Johnston 2014).

The article proceeds by developing hypotheses about intraparty polarization and US foreign policy, as well as describing the methodological approach to test them empirically. This is followed by a brief overview of the development of US trade policy since World War II, which shows how US trade policy has changed against the background of a declining bipartisan consensus. The article proceeds by measuring the extent of intraparty polarization via congressional letters and co-sponsorship alliances in two cases of US trade policy: The Transpacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), as well as the renegotiation of the North Atlantic Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), also known as the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA).

Finally, the article conducts a structured, focused comparison of how congressional distribution of trade policy preferences has influenced the outcome of both agreements. The USMCA is the first major trade agreement that passed Congress with a bipartisan majority since the end of the Cold War. In contrast, the TPP fell victim to congressional disagreement about US trade objectives and remained an executive agreement until the US withdrew from the agreement under the Trump administration. Comparing congressional preferences and ideological means with the substance of both trade deals sheds light on the conditions under which two trade agreements enjoy cross-partisanship support (or not) in contemporary American politics.

Intraparty polarization and U.S. foreign policy

Researchers have identified a growing partisan and ideological divide in American politics since the early 1970s. Data on individual legislators’ voting record in Congress show both parties have not only become more unified in congressional voting but have also become ideologically more homogenous (McCarty et al. 2016: 19; Levendusky 2009; Theriault 2008). Partisan and ideological sorting is in large part driven by simultaneous social identification as well as affective polarization, which has led to a decline in liberal Republicans and conservative Democrats (Abramowitz and Webster 2016; Iyengar and Krupekin 2018).

More recent research suggests that decades of partisan polarization have led to the rise of more extreme candidates within both parties, who have alienated more moderate voters from their party (Groenendyk et al. 2020). In contrast to interparty polarization, intraparty polarization is defined as a situation in which ideologically moderate and more extreme partisans are increasingly dispersed in their feelings toward their own party. Ideologically extreme partisans generally approve of their party’s shift to the extreme, whereas moderate partisans disapprove.

Groenendyk et al. (2020) find that moderate Democrats and Republicans have, over time, developed less positive feelings toward their party. In addition, the authors find the partisan ideological mean has become affectively polarized, yet the modal partisan has not. In other words, voter preferences have diverged between parties, yet they have not converged within them to a similar extent.Footnote 2 Instead, parties are becoming increasingly divided internally. Affective polarization has metastasized from being a key component of interparty contestation, warfare, and obstructionism, to fueling intraparty contestation and factionalism. As a result, intraparty polarization opens the political space for new realignments around anti-establishment and third-party candidates (Groenendyk et al. 2020: 1620).

Research on party factions in American politics has contributed to our understanding of patterns of cross-party cooperation in Congress (Rubin 2017; Koger et al. 2009), parties’ decision-making and political strategy toward organizing the legislative (diSalvo 2009; 2012), as well as drivers of institutional powershifts within parties (Clarke 2020; Blum 2020). Intraparty polarization holds three potential implications in the foreign policy realm: First, instead of manifesting a decline in bipartisanship, intraparty polarization suggests that new foreign policy crosscutting coalitions become possible. If the parties become intrinsically divided between moderate and ideologically more extreme partisans, we would assume that this affects the distribution of foreign policy preferences within the parties as well. A dispersion of foreign policy preferences within the parties would not only imply a potentially larger range of issues becoming more salient, but also that cross-party alignments around certain preferences become more feasible. Hence, it is assumed that intraparty polarization causes diversion between two or more salient policy preferences in contrast to party unity, which in turn increases the possibility for crosscutting coalitions along alternative policy cleavages.

Second, the emergence of new cleavages can open the space for new foreign policy entrepreneurs and factions to promote alternative policy preferences with the goal of shifting their party’s ideological disposition. While it certainly is true that party ideological means have become more polarized (McCarty et al. 2016: 19), new foreign policy entrepreneurs can cause gravitation toward certain ideological modes and thus contribute to the dispersion of party unity (cf. Marsh and Lantis 2016; Rubin 2017). In contrast to preference-based intraparty polarization, ideology-based intraparty polarization is driven by the intention to shift the party’s position instead of preventing success of the opposition through strong party unity.

Third, congruence and incongruence of preference-based and ideology-based intraparty polarization can influence the execution of US foreign policy. It is assumed that intraparty polarization is prevalent when trade preferences diverge within the parties and the respective ideological means are more dispersed within the parties than between them. It is hypothesized that ideology-based interparty polarization prohibits crosscutting coalitions on trade preferences.

With preferences more dispersed across parties, the executive is expected to choose a foreign policy strategy that entails more issue-linkages and side-payments. Issue-linkages are a common tool in negotiations to package deals by discussing two or more issues for joint settlement (Poast 2012). Side-payments are a tool to encourage concessions on a given issue through monetary payments or concessions on other issues (Frieman 1993). The more dominant these strategies are toward accommodating intraparty preferences for the outcome of negotiations, the more prominent intraparty polarization is in the eyes of the executive, shaping international negotiation strategies and outcomes. However, the ultimate success of such negotiation strategies (i.e., congressional support through ratification) is influenced by the degree of congruence of preference-based and ideology-based intraparty polarization.

Measuring intraparty polarization of US foreign policy

Existing research of intraparty polarization has focused primarily on voter preferences. This is reasonable given the plethora of survey data available alongside the ongoing debate whether polarization is caused by polarized elite cues or the radicalization of the American public (or both). However, measures to account for policy-based and ideological-based intraparty polarization in Congress are rare (cf. Homan and Lantis 2020).

The most common approach to identify differences among legislators’ policy preferences has been the reliance on roll-call voting patterns (McCarty et al. 2016). One major disadvantage of relying on roll-call votes alone is that it does not reveal much about the underlying preferences of legislators, that is, whether voting was motivated by party unity or by ideological conviction (Friedrichs 2021: 51–54). Evidence from partisan support under the Trump administration, for example, suggests that despite vocal criticism from so-called Never Trumpers, the Republican Party has witnessed high voting cohesiveness in terms of passing legislation supported by the president (Bycoffe and Silver 2020). In addition, political ideologies have so far been primarily conceptualized as broader accumulations of policy preferences, yet the link between locating legislators on a left–right ideological spectrum and identifying specific policy positions across policy domains is weak at best (cf. Rathbun 2007). Finally, relying on roll-call voting data when analyzing US foreign trade policy is problematic for another, more practical reason: Since international trade negotiations are usually conducted by the executive branch without an advice and consent role of Congress, members of Congress vote after trade agreements have been negotiated and signed, obscuring the development and influence of trade preferences over the course of international negotiations.

This paper measures congressional intraparty polarization by analyzing congressional co-sponsorship alliances for trade legislations as well as congressional letters to assess both the trade policy preferences of legislators and their ideological means over the course of international trade negotiations. Co-sponsorship and co-signing alliances can potentially differ from congressional voting patterns (cf. Bendix and Jeong 2020), which suggests that any causal assumption about trade preferences and ideological means, and the final voting decision by legislators should be taken with caution. Nevertheless, the data compiled here add to existing studies suggesting that prefloor legislative activities best reflect individual legislators’ preferences in contrast to final roll call voting data, which is more likely to be subject to partisan cues (cf. Bendix and Jeong 2020).

The analysis is conducted in three steps: In a first step, legislation and letters are collected for the timespan of the respective trade negotiations. In the case of the TPP, trade negotiations comprised the 111th until the 115th Congress, with a total of 86 pieces of legislation and 129 letters addressing TPP provisions. The UMSCA was negotiated during the 115th and 116th Congress, and members of Congress introduced a total of 54 pieces of legislation and wrote 32 letters to the executive addressing UMSCA provisions. It is important to note that although both datasets are representative of congressional trade preferences and their ideological distribution across and within parties, they do not reflect the entire congressional caucus since not all members of Congress participated in cosponsoring or letter writing.Footnote 3 However, it is argued here that vocal legislators over the course of trade negotiations are representative of their party factions’ trade preferences and ideological means.

Legislation and letters are then coded for their foreign policy preferences. Four trade preferences are available: Free trade, fair trade, trade reformist, and trade protectionist (cf. Cooper 2011: 14 ff.; Friedrichs 2021: 138–140). Free trade preferences favor lowering international trade barriers as a tool to foster economic growth that result from the positive economic effects of comparative advantages and free markets. Negative implications of the unequal distribution of trade benefits—affecting those segments of the economy that are unable to compete—will be compensated by the net benefits resulting from the competitiveness of those that benefit from increasing exports. As a result, states should export goods and services they can produce more efficiently and import those goods they can produce less efficiently.

Fair trade preferences acknowledge the net benefits of trade liberalization but contend that free trade also induces unfair conditions for US firms and workers. As developing countries pay lower wages and usually do not have equal labor standards, such as the right to bargain collectively, they put US workers and firms at a competitive disadvantage as they are confronted with heighten production costs, making them more vulnerable to imports from these countries. Hence, fair trade preferences come with expectations of trade agreements that provide for a “level playing field,” meaning strong enforcement mechanisms to allow for prescribed labor but also environmental standards.

Trade reformist preferences see the material costs of trade liberalization outweighing the benefits. Accordingly, US trade adversely affects general US economic interests, as US trade policy predominately benefit multinational corporations and conglomerates to the disadvantage of small businesses, workers, and farmers. To this extent, proponents call for a re-structuring of existing agreements and expect the rules of the World Trade Organization (WTO) and US-FTAs become more favorable for developing countries. In addition, trade reformist preferences also seek to revamp the domestic political authority in executing US trade policy, with a more assertive and stronger role of Congress vis-à-vis the executive branch. This includes reforming the trade promotion authority (TPA) in a way that gives Congress more weigh in during trade negotiations.

Trade protectionist preferences understand the power of tariffs and other trade barriers to solve domestic economic woes. US trade policy should change the negative effects of globalization, e.g., by restricting imports and foreign investment. Proponents oppose multilateral trade regimes and instead seek bilateral agreements that favor US economic actors and businesses. Instead of trusting in the regulative power of FTAs, they favor trade remedies to lower the trade deficit, which is perceived as a vulnerability for the US economy and its workers.

In a second step, co-sponsorship legislation and congressional letters are computed for their ideological mean in both DW-Nominate dimensions based on the individual legislators that have subscribed to the respective initiative. The first and second DW-Nominate dimension run along a socioeconomic and social cleavage, respectively. The second dimension highlights differences within the parties on issues that are usually excluded from the traditional socioeconomic dimension, e.g., race, civil rights, social issues, currency, or lifestyle issues. The second DW-Nominate dimension allows to identify additional ideology types, such as libertarians and populists. As such, libertarians and populists take on crosscutting positions about the role of the state as well as government institutions in relation to society and the individual (Holsti and Rosenau 1996; Rathbun et al. 2016; Carmines and D’Amico 2015). As these ideological groupings help us understand changes in the relative political power distribution between Republicans and Democrats, they also account for factions within the parties. Figure 1 depicts graphically the location of each ideological group in a two-dimensional ideology space.

In a third analytical step, the paper examines how these intraparty preferences have shaped the outcome of trade negotiations by the executive. A structured, focused comparison of the negotiations and ratification of the TPP and the USMCA is applied (George 2019; George and Bennett 2005). Concessions made by the executive to different trade factions within both parties reveal how much gravitational pull intraparty polarization can have. The goal is to assess what kind of preference-based and ideology-based intraparty polarization in each case had a plausible impact on the outcome of the respective trade negotiation.

A brief history of US trade policy and the breakup of domestic bipartisanship

Domestic bipartisanship for trade liberalization ensured the US has been a key pillar of the global free trading order in the post-World War II era. Against the background of the devastating effects of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act, the pre-eminence of the US economy, and the emergent security threat posed by the Soviet Union, the post-war consensus was that lowering tariffs and expanding free trade globally contributes to economic prosperity at home and security abroad, as well as generate long-term trust in the US liberal market system based on “fairness, transparency, and the rule of law” (Alessi and McMahon 2012). Domestic bipartisanship has allowed US foreign policy to facilitate trade liberalization through non-discrimination among trading partners and by promoting trade reciprocity.

This domestic consensus facilitated the creation of a multilateral trading regime. Under the most-favored-nation (MFN) norm within the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the USA helped to establish a global trading system that displaced the previous bilateral, neomercantilism, “beggar-thy-neighbor” system. A key element of US foreign policy was thereby to facilitate trade liberalization among both developed and developing countries. Congress made sure via the Uruguay Round Agreements Act to transform the GATT into the WTO. Through the WTO, the US set the agenda for a comprehensive global trading order that included substantial reductions in agricultural subsidies, export-restraint agreements (which, however, increased the use of anti-dumping or countervailing duties as safeguards from imports), the establishment of a dispute settlement procedure, as well as a General Agreement on Trade in Services, Trade-Related Intellectual Property, and Trade-Related Investment Measures. As a result, the global average MFN tariff rates decreased significantly after 1997 (Williams 2018).

Bipartisanship consensus for trade liberalization also resulted in a delegation of authority to negotiate FTAs to the executive. Via the Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act (RTAA) of 1934, the president was authorized to enter into reciprocal trade agreements without the need for additional legislation. The purpose of the RTAA was to increase US exports as well as incentivize other countries to foster free trade by reducing tariffs of mutual interest to the US and trading partners. With the Trade Act of 1974, Congress established the so-called fast track trade negotiating authority (TPA). TPA is time limited; instructs the executive branch on negotiating objectives and sets reporting and consultation requirements; eases the path of any resulting agreement through Congress; and retains for Congress the ultimate right to vote for or against an agreement (Ferguson 2015). In return, Congress established Trade Adjustment Assistance to provide compensation and retraining assistance to workers in industries most affected by trade liberalization, as well as “trade remedies” to address concerns from industries about international competition.

During the 1980s, worldwide exports grew on average 68 percent faster than the global GDP; in the 1990s, they grew nearly 140 percent faster. By the late twentieth century, due to a large-scale internationalization of US industries and their production, the US economy’s dependency on foreign trade exceeded prevalent doubts about trade competition. At the same time, growing trade in intermediate goods alongside technical improvements contributed to growing globalized trade. US firms increasingly sought revenues by expanding trade in goods and services and facilitated globally dispersed production networks, mainly due to improvements in transportation and communication (Irwin 2017).

Changes to the US domestic economy, coupled with the changing landscape of the global economy and trading partners increased domestic contestation about US trade liberalization after the Cold War. Domestic preferences deviated between stronger protection against growing trade imbalances (and potentially subsequent lower standards of living) and promoting global business ventures (Baldwin et al. 2000). Congress emphasized more strongly that a reduction of such non-tariff barriers is critical to advance multilateral trade liberalization. This became noticeable in the light of decreasing tariffs globally, which revealed the restrictive nature of non-tariff measures, such as government quotas, variable import levies, anti-dumping and countervailing duties, or voluntary export restraints (Friedrichs 2021: 127ff.).

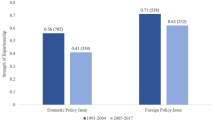

Following the passing of NAFTA in 1993, Congress witnessed sharp partisan divides over trade policy (Posadas 1996: 436). An increasing number of Democrats pressured the party leadership and argued that trade agreements were acceptable only if they had strong, enforceable provisions covering labor and environmental issues, which Republicans opposed as they felt these were prohibitive to trade liberalization as a motor for economic growth and prosperity (Ibid.: 440). This divide formed a breeding ground for domestic polarization between Democrats, who worried that the absence of such provisions would foster a race to the bottom on standards and subject domestic industries to unfair competition, and Republicans, who worried that such provisions were economically unsound and could be used as a backdoor to stricter labor and environmental regulation in the USA (Levy 2019). Figures 2 and 3 depict graphically the decline in bipartisanship consensus in the post-Cold War era for a US foreign policy that promotes trade liberalization. What is noticeable is that the decline in bipartisanship for trade liberalization was not necessarily caused by Democrats being homogenously opposed to free trade. Rather an anti-free trade faction among Democrats became more numerous and influential, causing congressional contestation in the form of decreasing congressional deference to the president, alongside stalling trade legislations (see below).

The domestic breakup of the bipartisanship consensus for trade liberalization brought three consequences to US foreign trade policy. First, ratification of negotiated FTAs has been contingent on Republican congressional majorities favoring free trade. Due to partisan polarization, all FTAs negotiated in the post-Cold War era (including NAFTA) were only ratified with a Republican majority in Congress. Democrats, in turn, slowly but steadily shifted their position away from supporting trade liberalization, mainly among those that feared freer trade would lead to adverse wage and employment effects on less educated and unionized workers (Baldwin et al. 2000: 2). In some cases, the ratification of negotiated FTAs—e.g., Panama, Peru, South Korea, and Colombia—was delayed for years, pending shifting congressional majorities.

Second, congressional TPA legislation suffered from gridlock, leading not only to fewer TPA legislation passed but also to longer periods without any updated trade legislation. This has been mainly due to stronger congressional partisan contestation about trade objectives. In the post-Cold war era, Congress only managed to pass two TPA legislation—the Trade Act of 2002 (narrowly one by the Bush administration by a single vote in the House, 215 to 214) and the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015 (which passed after several failed attempts with a bare minimum majority of 218 votes in the House and only 28 House Democrats supporting the bill). Longer periods without an updated TPA meant that trade negotiations had been primarily dictated by the executive branch and then retrospectively sought congressional approval. In the case of the Obama administration’s TPP, for instance, this resulted in non-consideration by Congress because once the administration signed the agreement with its Asia–Pacific trading partners after several years of negotiation, shifting majorities in Congress uploaded their trade preferences to an updated TPA legislation in 2015, which countervailed many of the TPP provisions (Friedrichs 2021: 151 ff.).

Third, despite fostering multilateral trade agreements, presidents focused on negotiating bilateral FTAs. Since the late 1990s, the USA has signed and ratified 14 bilateral FTAs with 20 different countries (Williams 2018: 6). This way, presidents sought to establish new trade norms for US trade liberalization, which seemed unachievable on a global multilateral level, especially in the light of concurrent legislation intended to withdraw from the WTO. Despite changes to the US economy, the evolution of individual, bilateral FTAs was also due to political shifts. Because new TPA legislation was difficult to pass through Congress, Democrats and Republicans repeatedly “bargained out” conditions for new trade agreements, for instance the so-called May 10th Agreement of 2007 between the Bush administration and Democrats.

Intraparty polarization and contemporary US trade policy

The Transpacific Partnership Agreement

The breakup of bipartisanship regarding US trade policy influenced both the Bush and Obama administration’s trade agenda of deepening interdependence with the Asia–Pacific region. After the 2006 mid-term elections, the Bush administration was forced to agree to the bipartisan May 10th Agreement in 2007 that updated the TPA-2002 congressional trade objectives in ways that reflected stronger trade rule enforcement and congressional control over US trade policy (Ferguson and Williams, 2016: 87), being more in line with the progressive wing in the Democratic party (Barfield and Levy 2009). Against the background of a contentious domestic political environment and a global rise in bilateral, regional trade agreements in response to stalling multilateral negotiations, the Bush administration sought to participate in the Transpacific Strategic Economic Partnership—an APEC free trade initiative later to be known as the TPP. The TPP was intended to integrate US trading partners into an updated and developed version of the global multilateral trading system, thereby doubling the share of US exports and imports with US trade agreement partners (Backer 2014). At the same time, Asia–Pacific countries saw an opportunity to gain more exclusive access to the US market.

Although Obama questioned the gains the USA had received from trade agreements in the past during his presidential campaign bid, as President he expanded his economic growth strategy and trade agenda amid the slow US economic recovery in the aftermath of the global financial crisis (United States Trade Representative 2008). The global economic slowdown impacted negatively on both the volume of global trade and the trade flows between countries. The Obama administration believed TPP offered the prospect of boosting US exports (Schott 2016: 12). With $1.5 trillion in merchandise in 2015 as well as more than $276 billion in services in 2014, the TPP posed significant potential for lowering trade barriers for shared economic gains (Fergusson and Williams 2016). In addition, the Obama administration believed TPP can strengthen global trade rules as well as facilitate domestic economic reforms in Asia–Pacific partner countries (Ravenhill, 2017). The Obama administration framed the TPP as a centerpiece of its “Pivot to Asia” strategy, which aimed to re-assure its Asia–Pacific allies and partners about US leadership against the background of an increasing Chinese assertion.

Shortly after Obama announced his intention to negotiate the TPP, a majority of House Democrats sponsored the Trade Reform Accountability Development and Employment (TRADE) Act. Although never put up for a vote, the legislation pushed for more progressive trade objectives beyond the May 10th agreement, including congressional oversight of trade agreements’ impact on the US economy; the level of democratization and compliance with human rights and labor standards of US trading partners; and a more assertive role of Congress in trade negotiations and trade enforcement. At the same time, a number of House Republicans signaled their opposition to any further expansion of free trade agreement standards beyond the May 10th agreement (Cooper 2011).

Congressional contestation remained prevalent throughout the TPP negotiations. The coding of trade policy preferences reveals that free trader and fair trade preferences equally polarized both parties, making up more than 60 percent of all preferences, whereas trade protectionist and trade reformist preferences oscillated at around 18 percent each. Neither party witnessed a clear majority of one particular trade preference but, overall, support for free trade was overwhelmingly supported in both parties, suggesting a shared preference across both parties in favor of free trade agreements. This finding is further supported by looking into the bipartisanship rates, with free trade (78%) and fair trade (75%) preferences enjoying the highest rates compare to trade reform (38%) and protectionist (43%) preferences. The fact that Obama strongly promoted the TPP did not incentivize Democrats to support free trade legislation or letters any more than Republicans. In fact, fair trade preferences outnumbered free trade preferences on the Democratic side, and vice versa on the Republican side.

Fair trade preferences were primarily concerned with intellectual property rights protection, especially biopharma innovations and patents, which are protected for up to 12 years under US domestic law. Another point of contention for legislators with fair trade preferences was the proper enforcement of trade rules in TPP trading partners in order to create an equal playing field for American workers and manufactures. Their main criticism was directed at Vietnam’s textile industry, Mexico’s labor laws, and Canada’s dairy market. In other areas, legislators demanded stronger regulation of state-owned enterprises and subsidies as non-tariff barriers to free trade. In return, legislators rejected so-called phase-out tariffs for sensitive US duties that would pose severe disadvantages to American industries competing with products from abroad.

Trade protectionist preferences in both parties were critical toward accession of individual member states, especially Japan and its automobile industry. Trade protectionist shared criticism of currency manipulation practices in certain TPP countries with fair traders. Legislators also bemoaned the trade deficit with TPP countries and proposed import tariffs on certain products as well as a buy American clause in TPP provisions. In addition, legislators criticized the investor-state-dispute-settlement body of the TPP, which they believed would increase foreign influence in the US economy.

Trade reformist preferences demanded stronger labor protection standards in accordance with the international labor organization as well as an overall strong commitment to the May 10th agreement, especially with regard to human rights protection. In addition, legislators proposed a reform of the TPA and the role of Congress in TPP negotiations, particularly with regard to their transparency.

Free trade preferences argued that the TPP would benefit the US textile manufacturing, particularly those that produce in TPP countries, and therefore supported a more flexible approach instead of the yarn-forward rule. They also sought lower tariffs for US dairy products in other countries. In addition, they argued that promoting free trade in the region would prevent a stronger Chinese influence.

The Obama administration took these domestic trade preferences into account when negotiating the TPP. First, the Obama administration negotiated asymmetric tariff reductions among TPP countries. While Australia, Chile, New Zealand, and Singapore were committed to comprehensive tariff liberalizations, Canada, Japan, and the USA maintained high tariffs on certain products (e.g., the USA implemented certain textile and apparel safeguards under the agreement). The Obama administration eventually negotiated bilaterally distinct tariff phase-outs and reductions with each TPP member state (Fergusson and Williams 2016). Through a side-agreement with Japan regarding non-tariff barriers on automobiles (e.g., tax breaks for domestic manufacturers or safety and environment regulations), the Obama administration sought to ease domestic concerns regarding Japan. In addition, the so-called yarn-forward rule was negotiated, which means that a country can rely on multiple TPP partners for its finished product to enjoy tariff benefits. Accommodating for a potential advantage of Vietnamese exporters, the TPP would have exempted some US apparel imports from Vietnam from the yarn-forward rule as long as Vietnam imports a specific quantity of US fabrics (Liang 2017).

Second, the Obama administration sought to balance domestic concerns about currency manipulation. The administration negotiated three provisions with TPP partners: a commitment to avoid manipulation through fair exchange rate policies (i.e., avoiding persistent exchange rate misalignments, as well as refraining from competitive devaluations); transparency and reporting through public data releases and annual assessments by the IMF; and a multilateral dialog between macroeconomic officials (Fergusson and Williams 2016). However, the administration was unable to regulate government procurements of goods and services, mainly because it would not abandon the Buy American clause written into US domestic law.

Third, the Obama administration sought a balance between intellectual property rights protection and national sovereignty. TPP entails extensions to patent and data beyond the May 10th Agreement. The USA had to mediate between poor member states—for which advocates demand quick availability of innovative pharmaceutical for public health reasons—and wealthy countries with branded pharmaceutical countries. This way, the Obama administration sought to harmonize patent, copyright, and trademark regimes throughout the TPP region. In addition, the Obama administration had to find a balance between protecting global investors (i.e., from discriminatory treatment) and TPP countries’ national sovereignty. The TPP would have addressed so-called indigenous innovation measures, which describes state-subsidized innovation that intends to discriminate foreign market intrusion innovation competition. Furthermore, TPP would have granted member states the right to deny ISDS challenging tobacco control measures to protect public health interests (Fergusson and Williams 2016).

Finally, TPP was a progressive attempt by the US to incite domestic reforms in countries with weak labor protections. The TPP provisions obligates members to a minimum wage, limits on working hours, as well as health and safety regulations (Cimino-Isaacs 2016: 262). However, due to various levels of development of each member, regulation discretion is left to each country. In addition, TPP obligates each member state to “effectively enforce its environmental laws through a sustained or recurring course of action or inaction to attract trade and investment” (Fergusson and Williams 2016: 63). These obligations were also supposed to be subject to dispute settlement procedures.

Although Congress granted the Obama administration TPA in the summer of 2015, albeit it failed to pass in a first attempt before it passed on a highly polarized vote, Senate Majority Speaker Mitch McConnell decided to not put TPP up for a vote under TPA provisions. Shortly after, House Speaker Paul Ryan decided against a vote on TPP. Since trade objectives had not been put into formal legislation for almost thirteen years since the last TPA legislation passed Congress, the polarized contestation of US trade leadership that was prevalent during TPP negotiations, prevented Congress from ratifying the TPP.

A look into the computed data on ideology-based intraparty polarization explains why—despite cross-partisan free and fair trade preferences—Congress was unable to ratify the TPP. As Figs. 4 and 5 below show, ideological interparty polarization remained strong. Ideology means of trade preferences did not reflect the same degree of dispersion within the parties. In other words, free trade and fair trade preferences were relatively equally polarized on the first and second DW-Nominate dimension. On both ideology dimensions, legislators were clustered around the party mean, preventing crosscutting coalitions on pro-TPP trade preferences.

In short, ideological means were polarized between the parties to similar degrees as their modal, suggesting a high degree of convergence and divergence between free trade and fair trade Democrats and Republicans. In sum, this suggests that despite the Obama administration’s attempts to balance domestic preferences in negotiation the TPP provisions internationally, ideological interparty polarization trumped preference-based intraparty polarization.

The US–Mexico–Canada Agreement

The post-Cold War era of the domestic breakup of bipartisanship consensus on US trade policy was interrupted by the 2020 congressional ratification of the USMCA. Passed with 385–41 votes in the House and 89–10 votes in the Senate, the USMCA constitutes the first major trade agreement passed by a bipartisan majority since 1988. The Trump administration’s negotiation with Canada and Mexico was authorized by the Bipartisan Congressional Trade Priorities and Accountability Act of 2015, Congress’ latest TPA, which was passed by a razor thin Republican majority during the Obama administration. As a result, congressional trade objectives under the 2015 TPA have not been shared by a bipartisan majority in Congress. Considering past congressional votes on FTAs under similar circumstances, particularly the highly polarized vote on NAFTA, the bipartisanship passing of USMCA presents an exception to an otherwise highly contentious US trade policy.

Similar to the TPP case, co-sponsorship legislation and congressional letters related to USMCA negotiations reveal that both parties were predominately polarized between free and fair traders. Free traders made up almost 45 percent in both parties compare to 40 percent fair traders. In terms of bipartisanship rates, all preferences enjoyed somewhat similar rates, with free traders 49%, fair traders 39%, trade protectionists 57%, and trade reformists 33%. Overall, the relative distribution of trade preferences vis-à-vis the USMCA suggests that both Democrats and Republicans were less polarized on partisan trade preferences but instead were polarized intrinsically along specific policy cleavages.

Free traders were primarily concerned with export restrictions as well as tariff impositions by the Trump administration as a tool to receive concessions from Canada and Mexico. Furthermore, free traders sought a reduction of free trade regulations in the areas of digital services, cross-border data flows and argued in favor of eliminating data and facilities localization requirements. They also demanded and expansion of energy exports and included provisions to facilitate e-commerce.

Fair traders demanded an elimination of special industry privileges, including ISDS mechanisms, job offshoring incentives, and required "Buy American" waivers. In addition, they pushed for US food safety and public health standards, as well as enforceable disciplines against currency manipulation, anti-dumping and countervailing duties, and an inclusion of high labor and environmental standards.

The Trump administration’s negotiation approach to the USMCA were sensitive to these intraparty dispersions of trade preferences and ideological factions. A key goal for the Trump administration was to reform NAFTA in terms of balancing and reducing the US trade deficit with Mexico and Canada. In the end, the USMCA retained most of NAFTA’s market-opening commitments, while making changes to market access for autos and agriculture products, as well as to investment, government procurement and intellectually property rights (Congressional Research Service 2020: 13 ff.). As such, the agreement is a somewhat odd update to the 1993 NAFTA agreement because on the one hand, it accommodates fair trade Democrats demands for stronger trade enforcement rules on labor rights and environmental laws and, on the other hand, includes trade protectionist elements that impedes economic growth. Overall, the impact of intraparty polarization is explicit in three areas of the USMCA:

First, USMCA provisions on auto trade increase regional content required for duty-free treatment of automotive, steel, and aluminum products. In a nutshell, these regional content requirements (i.e., goods entering duty free must have certain percentages of content produced in the region) will raise production costs, auto prices, as well as reduce US demand and auto exports. These provisions were not contested by fair trade Democrats because trade regionalization was linked to tougher protections and enforcement of labors rights and environmental policies. In fact, final amendments to the USMCA bill added further restrictions, namely that 70 percent of steel purchased by vehicle assemblers must originate in the region and virtually all steel must be processed entirely within North America (Lovely and Schott 2019).

Second, the Trump administration made significant changes to the dispute settlement procedures under the USMCA, particularly to strengthen enforcement of labor and environmental obligations. Whereas previously, complainants had to prove that violation of labor and environmental standards harm trade, the revised USMCA reverses this necessary presumption, increasing the prospect of a broader range of litigations. In return, fair trade Democrats, who pushed hard for this provision being included in the agreement, withheld their demand to force Canada and Mexico to join previously negotiated multilateral environmental agreements, covering the protection of endangered species, ozone regulations, or marine pollution. Moreover, Democrats did not insist to include the Paris Accord into the list.

Third, the USMCA ended up with weaker pharmaceutical patent provisions than initially negotiated by the Trump administration, mainly with respect to access to market generic drugs for Mexico and Canada. Fair trade Democrats have, in the past, demanded changes to US domestic law, which foresees a 12-year data exclusivity timeframe for expensive patented drugs before being introduced to US markets. Under the USMCA, neither is Mexico and Canada forced into longer data exclusivity periods for their own market, nor has US domestic law changed to make generic, cheaper drugs more quickly available for US consumers. Particularly Senate free trade Republicans strongly opposed the latter, potentially jeopardizing the agreement in case fair trade Democrats would not have withdrawn from their traditional demands.

A look at the ideological drivers for trade preferences regarding USMCA within both parties reveals the extent to which these trade preferences were further ideologically polarized within both parties (see Figs. 6 and 7). A majority of co-sponsors and co-signatories, both of free trade and fair trade preferences, are relatively moderate on the first DW-Nominate dimension, yet fairly spread out on the second ideological dimension, particularly in the Senate. Trade protectionists, in contrast, remained much more clustered around the partisan mean on both DW-nominate dimensions. Despite including some protectionist measures, the USMCA did not convince those trade protectionists in Congress as there is a strong overlap between voicing trade protectionist preferences during negotiations and voting against ratification of the negotiated agreement.

In sum, the analysis suggests that the combination of preference-based and ideology-based intraparty polarization foregrounded crosscutting coalitions in favor of free trade. The Trump administration thereby sought to link issues that generated support by free trade and trade protectionist factions. Yet in contrast to the Obama administration, legislators proved less ideologically unified, thus shifting the ratification pivot away from the party mean, closer to the ratification pivot.

Conclusion

The article introduced intraparty polarization, as an offspring of interparty polarization, to the study of contemporary US foreign policy. It examined the impact of intraparty polarization in two contemporary cases of US trade policy: the negotiation of TPP under the Obama administration and the renegotiation of NAFTA, the USMCA under the Trump administration. Intraparty polarization was measured via a new data set consisting of congressional co-sponsorship legislation and co-signed letters, revealing the extent of intraparty dispersion of trade preferences and their ideological means. It was hypothesized that an incongruence of preference and ideology-based intraparty polarization can prohibit crosscutting coalitions for changes in US trade policy, whereas a congruence of preference and ideology-based intraparty polarization can facilitate crosscutting coalitions for changes in US trade policy.

The analysis revealed that both parties are highly internally polarized, primarily between free and fair traders. More importantly, analysis of ideological correlates on the first and second DW-Nominate dimensions exposed that although both parties are ideologically diverged, variance in the ideological dispersion within both parties regarding the various trade preferences correlated with levels of congressional support for trade agreements. Furthermore, the empirical analysis of both cases revealed that both administrations engaged in issue-linkages and concessions but the relative success of their strategies was largely dependent on the relative congruence of intraparty preference and ideology polarization. Polarization of trade preferences within the parties possessed gravitational pull in the case of the USMCA but not in the case of TPP. In other words, congruence of preference-based and ideology-based intraparty polarization led to congressional support for the USMCA ratification, whereas incongruence of preference-based and ideology-based intraparty polarization (but instead stronger ideology-based interparty polarization) prevented congressional support for TPP ratification.

The analysis of trade preferences and their ideological underpinnings contributes to work on bipartisanship realignments in the foreign policy realm. In short, the analysis of both cases has revealed that cross-partisanship is possible when ideological polarization between the parties is low relative to ideological-based intraparty polarization. In sum, the paper provided some evidence for an increasing relevance of intraparty polarization for both the domestic alignment around new trade preferences and the outcome of US trade negotiations. It has thereby contributed to the emerging literature on domestic polarization and US foreign policy by theorizing how continuous polarization can in fact cause ideologically dispersion within the parties, with serious consequences for the execution and success of US foreign policy.

Notes

It should be noted that in this article, “bipartisan” is understood as a situation when a majority of lawmakers in the two parties vote together (cf. Bryan and Tama Bycoffe and Silver 2020). I want to thank the anonymous reviewer for clarifying this point.

This observation confirms to some extent the assumption that the American public is still less polarized than their political representatives but have fewer options to express their preferences due to polarized cues (Fiorina et al. 2011).

I am thankful to Jordan Tama for making me mindful of this.

References

Abramowitz, A., and S. Webster. 2016. The rise of negative partisanship and the nationalization of U.S. elections in the 21st century. Electoral Studies 41: 12–22.

Abramowitz, A.I. 2018. The great alignment: Race, party transformation, and the rise of donald trump. London: Yale University Press.

Alessi, C. and Mcmahon, R. 2012. U.S. Trade Policy. Congressional Research Service, Backgrounder.

Backer, L.C. 2014. The trans-pacific partnership: Japan, China, the U.S., and the emerging shape of a new world trade regulatory order. Washington University Global Studies Law Review 13: 49–81.

Baldwin, R.E., C.S. Magee, and I.M. Destler. 2000. Congressional trade votes: From NAFTA approval to fast-track defeat. Washington, D.C.: Institute for International Economics.

Barfield, C. & Levy, P. I. 2009. In Search of an Obama Trade Policy [Online]. American Enterprise Institute. Available: https://www.aei.org/research-products/report/in-search-of-an-obama-trade-policy/ [Accessed February 1 2021].

Bendix, W. & Jeong, G.-H. 2020. Beyond Party: Ideological Convictions and Foreign Policy Conflicts in the US Congress. Workshop Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Implications. Heidelberg University.

Binder, S. 2015. The dysfunctional congress. Annual Review of Political Science 18: 85–101.

Blum, R.M. 2020. How the tea party captured the gop insurgent factions in American politics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Bown, C. P. 2020. Trump's phase one trade deal with China and the US election [Online]. Peterson Institute for International Economics. Available: https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/trumps-phase-one-trade-deal-china-and-us-election [Accessed October 30 2020].

Bryan, J. and Tama, J. 2020. The Prevalence of Bipartisanship in U.S. Foreign Policy: An analysis of important congressional votes. Workshop Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Implications. Heidelberg University.

Bycoffe, A. and Silver, N. 2020. Tracking Congress in the age of trump [Online]. FiveThirtyEight. Available: https://projects.fivethirtyeight.com/congress-trump-score/ [Accessed October 26 2020].

Campbell, J.E. 2016. Polarized: Making sense of a divided America. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Carmines, E.G., and N.J. D’Amico. 2015. The new look in political ideology research. Annual Review of Political Science 18: 205–216.

Chaudoin, S., H.V. Milner, and D.H. Tingley. 2010. The center still holds: Liberal internationalism survives. International Security 35: 75–94.

Cimino-Isaacs, C. 2016. Labor Standards in the TPP. In Trans-Pacific Partnership: An Assessment, ed. C. Cimino-Isaacs, and J.J. Schott. Washington, D.C.: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Clarke, A.J. 2020. Party sub-brands and American party factions. American Journal of Political Science 64: 452–470.

Congressional Research Service. 2020. The United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA). Congressional Research Service, R44981.

Cooper, W. H. 2011. The Future of U.S. Trade Policy: An Analysis of Issues and Options for the 112th Congress. Congressional Research Service, R41145.

Curry, J.M., and F.E. Lee. 2020. The limits of party: Congress and lawmaking in a polarized era. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

DiSalvo, D. 2009. Party Factions in Congress. Congress & the Presidency 36: 27–57.

DISALVO, D. . 2012. Engines of change: Party factions in American politics, 1868–2010. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feldman, S., and C. Johnston. 2014. Understanding the determinants of political ideology: Implications of structural complexity. Political Psychology 35: 337–358.

Fergusson, I. F. and Williams, B. R. 2016. The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): Key provisions and issues for congress. Congressional Research Service, R44489.

Fergusson, I. F. 2015. Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) and the Role of Congress in Trade Policy. Congressional Research Service, RL33743.

Fiorina, M.P., S.J. Abrams, and J.C. Pope. 2011. Culture war? The myth of a polarized America. New York: Pearson.

Ford, R., and W. Jennings. 2020. The changing cleavage politics of Western Europe. Annual Review of Political Science 23: 295–314.

Friedrichs, G. 2021. U.S. global leadership role and domestic polarization: A role theory approach. New York: Routledge.

Friman, H.R. 1993. Side-payments versus security cards: Domestic bargaining tactics in international economic negotiations. International Organization 47: 387–410.

George, A.L., and A. Bennett. 2005. Case studies and theory development in the social sciences. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

George, A.L. 2019. Case studies and theory development: The method of structured, focused comparison. In Alexander L. George: A pioneer in political and social sciences, ed. Dan Caldwell. Cham: Springer.

Green, M. & Lauter, L. 2020. Congress will have return to bipartisan policy with China [Online]. Available: https://thehill.com/opinion/international/522277-congress-will-have-return-to-bipartisan-policy-with-china [Accessed October 31 2020].

Groenendyk, E., M.W. Sances, and Kirill Zhirkov. 2020. Intraparty polarization in American Politics. Journal of Politics 82: 1616.

Holsti, O.R., and J. Rosenau. 1996. Liberals, populists, libertarians, and conservatives: The link between domestic and international affairs. In Making American Foreign Policy, ed. O.R. Holsti. New York: Routledge.

Homan, P., and J.S. Lantis. 2019. The battle for U.S. foreign policy: Congress, parties, and factions in the 21st century. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Homan, P. & Lantis, J. S. 2020. Foreign policy free agents: How Lawmakers and Coalitions on the Political Margins Help Set Boundaries for U.S. Foreign Policy. Workshop Domestic Polarization and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ideas, Institutions, and Policy Implications. Heidelberg University.

Hurst, S., and A. Wroe. 2016. Partisan polarization and US foreign policy: Is the centre dead or holding. International Politics 53: 666–682.

Insidetrade. 2011. Brady hopes congress will consider fast-track for TPP, Other Trade Initiatives [Online]. Available: https://insidetrade.com/daily-news/brady-hopes-congress-will-consider-fast-track-tpp-other-trade-initiatives [Accessed February 1 2021].

Irwin, D.A. 2017. Clashing over commerce: A history of US trade policy. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Irwin, D.A. 2020. Trade policy in American economic history. Annual Review of Economics 12: 23–44.

Iyengar, S., and M. Krupenkin. 2018. Partisanship as social identity: Implications for the study of party polarization. Forum 16: 23–46.

Jeong, G.-H., and P.J. Quirk. 2019. Division at the water’s edge: The polarization of foreign policy. American Politics Research 47: 58–87.

Kertzer, J.D., and R. Brutger. 2015. Decomposing audience costs: Bringing the audience back into audience cost theory. American Journal of Political Science 60: 234–249.

Koger, G., S. Masket, and H. Noel. 2009. Cooperative party factions in American politics. American Politics Research 38: 33–53.

Kupchan, C.A., and P.L. Trubowitz. 2007. Dead Center The Demise of Liberal Internationalism in the United States. International Security 32: 7–44.

Kurtzleben, D. 2017. Here's How Many Bernie Sanders Supporters Ultimately Voted For Trump [Online]. NPR. Available: https://www.npr.org/2017/08/24/545812242/1-in-10-sanders-primary-voters-ended-up-supporting-trump-survey-finds?t=1603644754678&t=1603731247069 [Accessed October 25 2020].

Lantis, J. S. & Homan, P. 2018. Factionalism and US Foreign Policy: A Social Psychological Model of Minority Influence. Foreign Policy Analysis, 1–19.

Lee, F.E. 2015. How party polarization affects governance. Annual Review of Political Science 18: 261–282.

Lee, F.E. 2018. The 115th congress and questions of party unity in a polarized era. The Journal of Politics 80: 1464–1473.

Levendusky, M. 2009. The Partisan Sort. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levy, P. 2019. Rebuilding a Bipartisan Consensus on Trade Policy. In: Affairs, C. C. O. G. (ed.). Chicago: Chicago Council on Global Affairs.

Liang, M. 2017. Rules of origin in the trans-pacific partnership. In Paradigm shift in international economic law rule-making: TPP as a new model for trade agreements?, ed. J. Chaisse, H. Gao, and C.-F. Lo. Singapore: Springer.

Lovely, M. E. & Schott, J. J. 2019. The USMCA: New, Modestly Improved, but Still Costly [Online]. Peterson Institute for International Economics. Available: https://www.piie.com/blogs/trade-and-investment-policy-watch/usmca-new-modestly-improved-still-costly [Accessed October 30 2020].

Marsh, K. & Lantis, J. S. 2016. Are all foreign policy innovators created equal? The new generation of congressional foreign policy entrepreneurship. Foreign Policy Analysis, 1–23.

McCarty, N., K.T. Poole, and H. Rosenthal. 2016. Polarized America: The dance of ideology and unequal riches. Cambridge, London: The MIT Press.

Milner, H.V., and D.H. Tingley. 2011. Who supports global economic engagement? The sources of preferences in American Foreign Economic Policy. International Organization 65: 37–68.

Milner, H.V. 1997. Interests, institutions, and information: Domestic politics and international relations. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Noel, H. 2016. Ideological factions in the republican and democratic parties. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 667: 166–188.

Ohlemacher, S. & Barrow, B. 2020. Biden reaches deal to let Sanders keep hundreds of delegates [Online]. AP News. Available: https://apnews.com/article/1250a619e0c8195fad1aa6aea08c63c8 [Accessed October 26, 2020].

Poast, P. 2012. Does Issue Linkage Work? Evidence from European Alliance Negotiations, 1860 to 1945. International Organization 66: 277–310.

Politi, J. 2020. What’s in the US-China ‘phase one’ trade deal? [Online]. Financial Times. Available: https://www.ft.com/content/a01564ba-37d5-11ea-a6d3-9a26f8c3cba4 [Accessed November 1 2020].

Posadas, A. 1996. NAFTA’s Approval: A story of congress at work “From International Relations To National Accountability.” ILSA Journal of International and Comparative Law 2: 433–451.

Putnam, R.D. 1988. Diplomacy and domestic politics: The logic of two-level games. International Organization 42: 427–460.

Rathbun, B.C., J.D. Kertzer, J. Reifler, P. Goren, and T.J. Scotto. 2016. Taking foreign policy personally: Personal values and foreign policy attitudes. International Studies Quarterly 60: 124–137.

Rathbun, B.C. 2007. Hierarchy and community at home and abroad: Evidence of a common structure of domestic and foreign policy beliefs in American Elites. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 51: 379–407.

Rathbun, B.C. 2016. Wedges and widgets: Liberalism, libertarianism, and the trade attitudes of the American mass public and elites. Foreign Policy Analysis 12: 85–108.

Ravenhill, J. 2017. The political economy of the Trans-Pacific Partnership: A ‘21st Century’ trade agreement? New Political Economy 5: 573–594.

Rho, S., and M. Tomz. 2017. Why don’t trade preferences reflect economic self-interest? International Organization 71: 85–108.

Rubin, R.B. 2017. Building the Bloc: Intraparty organization in the US Congress. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Saldin, R.P., and S.M. Teles. 2020. Never trump: The revolt of the conservative elites. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schaffner, B.F. 2011. Party polarization. In The oxford handbook of the American Congress, ed. G.C.E. Iii, F.E. Lee, and E. Schickler. New York: Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Schneider, C. J. 2018. The domestic politics of international cooperation. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics [Online]. Available: https://oxfordre.com/politics/view/https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.001.0001/acrefore-9780190228637-e-615.

Schott, J.J. 2016. Overview: Understanding the trans-pacific partnership. In Trans-pacific partnership: An assessment, ed. C. Cimino-Isaacs and J.J. Schott. Washington, D.C: Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Schultz, K.A. 2012. Why we needed audience costs and what we need now. Security Studies 21: 369–375.

Schultz, K.A. 2017. Perils of polarization for U.S. Foreign Policy. The Washington Quarterly 40: 7–28.

Snyder, J., R.Y. Shapiro, and Y. Bloch-Elkon. 2009. Free hand abroad, divide and rule at home. World Politics 61: 155–187.

Tama, J. 2020. Forcing the president’s hand: How the US congress shapes foreign policy through sanctions legislation. Foreign Policy Analysis 16: 397–416.

Tarar, A. 2005. Constituencies and preferences in international bargaining. Journal of Conflict Resolution 49: 383–407.

Theriault, S.M. 2006. Party polarization in the US Congress: Member replacement and member adaptation. Party Politics 12: 483–503.

Theriault, S.M. 2008. Party polarization in congress. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thomsen, D.M. 2017. Opting out of congress: Partisan polarization and the decline of moderate candidates. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Trubowitz, P., and P. Harris. 2019. The end of the American century? Slow erosion of the domestic sources of usable power. International Affairs 95: 619–639.

Trubowitz, P., and N. Mellow. 2011. Foreign policy, bipartisanship and the paradox of post-September 11 America. International Politics 48: 164–187.

United States Trade Representative. 2008. Trans-Pacific Partnership Announcement [Online]. Available: https://ustr.gov/about-us/policy-offices/press-office/press-releases/2009/december/trans-pacific-partnership-announcement [Accessed February 1 2021].

Williams, B. R. 2018. Bilateral and regional trade agreements: Issues for Congress. Congressional Research Service, R45198.

Wronski, J., A. Bankert, A.A. Johnson, and L.C. Levitan. 2018. A tale of two democrats: How authoritarianism divides the democratic party. The Journal of Politics 80: 1384–1388.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

I am grateful to Jonas Gockel for research assistance.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Friedrichs, G.M. Polarized we trade? Intraparty polarization and US trade policy. Int Polit 59, 956–980 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00344-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41311-021-00344-x