Abstract

This paper contributes to the open economy local fiscal multiplier literature by estimating regional output and employment responses to federal expenditure shocks in the European Union. In particular, similarly to the literature on foreign aid and growth, I use shocks to the supply of federal transfers (European Commission commitments) of structural fund spending by subnational region as instruments for annual realized expenditure in a panel from 2000–2013. I find a large, contemporaneous multiplier of 1.8 which translates into a medium-run multiplier of 4.1 three years after the shock. Furthermore, using a novel dataset on bilateral trade between EU regions, I find evidence of demand-driven spillovers up to 2 years after a shock.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A priori, one could expect these multipliers to be different in the USA and Europe due to non-trivial differences in institutional constraints and characteristics of financial services, goods markets and labor mobility, for example.

NUTS stands for Nomenclature des Unités Territoriales Statistiques used by Eurostat. At their most aggregated level (NUTS 1), they roughly correspond to Germany’s Bundesländer with an approximate minimum of 3 million people; NUTS 2 range between 800,000 and 3 million people, with NUTS 3 comprising the smallest of the aggregates, equivalent to French Départements. Currently there are a total of 97 regions at NUTS 1, 271 regions at NUTS 2 and 1303 regions at NUTS 3 level.

Those under Objective 1 of the Cohesion Policy. Estimated coefficients of interest are adjusted for co-financing of 40% on average by private entities and local/national governments.

Close to 88% in the 2000–2006 programming period, and 97% in the 2007–2013 period.

As of June 2018, this formula was in the process of changing to include new criteria, such as youth unemployment, education levels, immigration, and carbon emissions (Financial Times 2018).

Whether this principle is actually binding is debatable. There is plausible reason to believe in fact some of these transfers are substituting, rather than adding to, local public spending.

With the exception of the United Kingdom.

Note that Nakamura and Steinsson (2014) use a 2-year cumulative shock, rather than annual.

Doing so would eliminate most of the cross-sectional variation between NUTS 2 regions, since these only vary by programming period and not by year, except insofar as their home state pattern also changes.

Unfortunately, given the short span of my time series, I cannot use Driscoll-Kraay HAC standard errors; for consistency, these need a time dimension where \(T>20-25\).

In particular, in each regression I exclude the most influential observations—defined as those with Cook’s distance greater than 1 in the simpler OLS regression of the outcome variable on the instrumental variable. In the baseline specifications this implies dropping 22 data points for Objective 1 regions (such as EE 2009 and LT 2009) and 28 for Objective 2 regions (such as SE33 2010 and NL11 2008). These are mostly observations with abnormally sharp output fluctuations and very low transfers changes. Their inclusion does not significantly affect the quantitative results in the paper—it lowers the Objective 1 contemporaneous multiplier estimate to 1.54 and increases the medium-run multiplier at the 3-year horizon to 4.6. In addition, I also exclude UK regions from Objective 2 regressions; in contrast to the previous outliers, including these observations would substantially affect the results for Objective 2 regions, turning the contemporaneous output multiplier positive and significant. However, this is disproportionately driven by extremely small expenditure changes, leading to unreasonably high multiplier estimates for the UK alone, so I chose to exclude the country from Objective 2 results presented here altogether.

There are printed sources for annual regional commitments and expenditures 1994–1999, which can be used to expand the current database going back 5 years. This is ongoing work.

Sweco ex-post consulting report to the European Commission.

I am very grateful to Emmanuel Farhi, Iván Werning, Raphael Corbi, Elias Papaioannou, and Paolo Surico for kindly sharing the codes for their respective implementations.

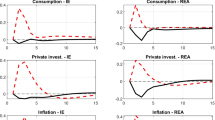

In particular, the elasticity of intertemporal substitution is set to 1, the elasticity of substitution between local and foreign goods, as well as between goods produced in different foreign countries, is set to 1, the elasticity of substitution between varieties produced in a given country to 6, and the elasticity of labor supply to 3.

Assuming a constant MPC across the business cycle, consumption and disposable income series should track each other closely. Note this assumption neglects any effects of government spending on household precautionary saving motives, such as that identified by Ercolani and Pavoni (2014).

Objective 2 regions also do receive some transfers. Although not as sizable as median Objective 1 transfers, the former are still “treated” observations, even while being a valid control group for Objective 1 regions. That continuity in treatment beyond the Objective 1 threshold is a feature often neglected by previous literature using the methodology in this section.

There is also data on expenditures at the NUTS3 level for the 2000–2006 period, but instruments exist at the NUTS 2 level only (by design). See Becker et al. (2012), who use this shorter period but more disaggregated dataset in a generalized propensity score setup.

The results are robust to their exclusion.

Restricting the analysis as in Imbens and Lemieux (2008) to a narrow band around the threshold (rather than using the entire sample) would eliminate the results presented here, partially due to smaller sample size, but also due to the similarity in outcomes around the threshold evidenced in the graphs above.

Becker, Egger and von Ehrlich find that correlation for the 1989–1993, 1994–1999 and 2000–2006 programming periods, although looking at the fine print, the 1994–1999 effect on average GDP growth they measure using RDD is only significant at the 15% level, and in all cases the coefficient is around 1% (so that treated regions grow on average 1% a year more than non-treated ones).

References

Alston, Julian M., Matthew A. Andersen, Jennifer S. James, and Philip G. Pardey. 2010. Persistence pays: U.S. agricultural productivity growth and the benefits from public R&D spending. Natural Resource Management and Policy 34: 238–267.

Ampudia, Miguel, Dimitris Georgarakos, Jiri Slacalek, Oreste Tristani, Philip Vermeulen, and Giovanni L. Violante. 2018. Monetary policy and household inequality. Working Paper Series 2170, European Central Bank.

Arnold, Nathaniel, Bergljot Barkbu, Elif Ture, Hou Wang, and Jiaxiong Yao. 2018. A Central Fiscal Stabilization Capacity for the Euro Area. IMF Staff Discussion Note 18/03, International Monetary Fund.

Auerbach, Alan J., and Yuriy Gorodnichenko. 2012. Fiscal multipliers in recession and expansion. In Fiscal Policy after the Financial Crisis, NBER Chapters, 63–98. National Bureau of Economic Research Inc.

Auerbach, Alan J., and Yuriy Gorodnichenko. 2013. Output spillovers from fiscal policy. American Economic Review 103(3): 141–46.

Bargain, Olivier, Mathias Dolls, Clemens Fuest, Dirk Neumann, Andreas Peichl, Nico Pestel, and Sebastian Siegloch. 2013. Fiscal union in Europe? Redistributive and stabilizing effects of a European tax-benefit system and fiscal equalization mechanism. Economic Policy 28(75): 375–422.

Becker, Sascha O., Peter H. Egger, and Maximilian von Ehrlich. 2010. Going NUTS: The effect of EU Structural Funds on regional performance. Journal of Public Economics 94(9–10): 578–590.

Becker, Sascha O., Peter H. Egger, and Maximilian von Ehrlich. 2012. Too much of a good thing? On the growth effects of the EU’s regional policy. European Economic Review 56(4): 648–668.

Becker, Sascha O., Peter H. Egger, and Maximilian von Ehrlich. 2013. Absorptive capacity and the growth and investment effects of regional transfers: A regression discontinuity design with heterogeneous treatment effects. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 5(4): 29–77.

Becker, Sascha O., Peter H. Egger, and Maximilian von Ehrlich. 2018. Effects of EU regional policy: 1989–2013. Regional Science and Urban Economics 69: 143–152.

Bernanke, Ben S., Mark Gertler, and Simon Gilchrist. 1999. The financial accelerator in a quantitative business cycle framework. In Handbook of Macroeconomics, Vol. 1 of Handbook of Macroeconomics, ed. J.B. Taylor, and M. Woodford, 1341–1393. Amsterdam: Elsevier. (chapter 21).

Beugelsdijk, Maaike, and Sylvester C.W. Eijffinger. 2005. The effectiveness of structural policy in the european union: An empirical analysis for the EU-15 in 1995–2001. Journal of Common Market Studies 43(1): 37–51.

Blagrave, Patrick, Giang Ho, Ksenia Koloskova, and Esteban Vesperoni. 2018. Cross-border transmission of fiscal shocks: The role of monetary conditions. IMF Working Papers 18/103, International Monetary Fund.

Blanchard, Olivier, and Roberto Perotti. 2002. An empirical characterization of the dynamic effects of changes in government spending and taxes on output. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 117(4): 1329–1368.

Blanchard, Olivier, Roberto Perotti, Christopher J. Erceg, and Jesper Lindé. 2016. Jump-starting the euro area recovery: Would a rise in core fiscal spending help the periphery?. Working Paper 21426, NBER.

Bruckner, Markus, and Anita Tuladhar. 2011. The effectiveness of government expenditures during crisis: Evidence from regional government spending in Japan 1990–2000. School of Economics Working Papers, University of Adelaide, School of Economics 2011-10, University of Adelaide, School of Economics.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel. 2019. Geographic cross-sectional fiscal spending multipliers: What have we learned? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, American Economic Association 11(2): 1–34.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel, Laura Feiveson, Zachary Liscow, and William Gui Woolston. 2012. Does state fiscal relief during recessions increase employment? Evidence from the American recovery and reinvestment act. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 4(3): 118–45.

Clemens, Michael, Steven Radelet, and Rikhil Bhavnani. 2004. Counting Chickens when They Hatch: The Short-Term Effect of Aid on Growth. International Finance, EconWPA.

Cohen-Setton, Jeremie, Egor Gornostay, and Colombe Ladreit de Lacharriere. 2019. Large fiscal expansions in OECD countries: Identification and effects. PIIE Working Paper, Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Corbi, Raphaeli, Elias Papaioannou, and Paolo Surico. 2018. Regional Transfer Multipliers. The Review of Economic Studies. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdy069.

Dixon, H., and H. Le Bihan. 2011. Generalized Taylor and generalized Calvo price and wage-setting: micro evidence with macro implications. Working papers 324, Banque de France 2011.

Economides, George, Apostolis Philippopoulos, and Petros Varthalitis. 2016. Monetary union, even higher integration, or back to national currencies? CESifo Working Paper Series 5762, CESifo Group Munich 2016.

Ederveen, Sjef, Henri L.F. Groot, and Richard Nahuis. 2006. Fertile soil for structural funds? A panel data analysis of the conditional effectiveness of european cohesion policy. Kyklos 59(1): 17–42.

Elekdag, Selim and Dirk Muir. 2014. Das Public Kapital; How Much Would Higher German Public Investment Help Germany and the Euro Area?, IMF Working Papers 14/227, International Monetary Fund December 2014.

Ercolani, Valerio, and Nicola Pavoni. 2014. The precautionary saving effect of government consumption. CEPR Discussion Papers 10067, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers July 2014.

European Commission. 2010. General provisions ERDF-ESF-Cohesion Fund (2007–2013).

European Commission. 2015. The European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI) programme. http://ec.europa.eu/priorities/jobs-growth-investment/plan/efsi/index_en.htm. Accessed November 16, 2015.

European Commission. 2016. What is new in EFSI 2.0?. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/efsi− 2.0-factsheet_en.pdf. Accessed January 06, 2018.

Farhi, E., and I. Werning. 2016. Fiscal multipliers: Liquidity traps and currency unions. Vol. 2 of Handbook of macroeconomics. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Fatas, Antonio, and Ilian Mihov. 2001. The effects of fiscal policy on consumption and employment: Theory and evidence. CEPR Discussion Papers, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers 2760, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers .

Financial Times. 2018. EU plans EUR30bn funding shift from central and eastern Europe. https://www.ft.com/content/c35f032a-628b-11e8-90c2-9563a0613e56. Accessed January 06, 2018.

Florio, Massimo, and Luigi Moretti. 2014. The effect of business support on employment in manufacturing: Evidence from the European union structural funds in Germany, Italy and Spain. European Planning Studies 22(9): 1802–1823.

Gali, Jordi. 2015. Hysteresis and the European unemployment problem revisited. Working Paper 21430, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Gali, Jordi, and Tommaso Monacelli. 2008. Optimal monetary and fiscal policy in a currency union. Journal of International Economics 76(1): 116–132.

Giavazzi, Francesco, and Marco Pagano. 1990. Can severe fiscal contractions be expansionary? Tales of two small european countries. In NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1990, Volume 5 NBER Chapters, 75–122. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Grauwe, Paul De and Wim Vanhaverbeke. 1991 Is Europe an optimum currency area? Evidence from regional data. CEPR Discussion Papers 555, C.E.P.R. Discussion Papers.

Greenstone, Michael, Richard Hornbeck, and Enrico Moretti. 2010. Identifying agglomeration spillovers: Evidence from winners and losers of large plant openings. Journal of Political Economy 118(3): 536–598.

Hall, Robert E. 2009. By how much does GDP rise if the government buys more output? Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Economic Studies Program, The Brookings Institution 40(2 (Fall)): 183–249.

Heijman, Wim, and Tobias Koch. 2011. The allocation of financial resources of the EU Structural Funds and Cohesion Fund during the period 2007–2013. Agricultural Economics 57(2): 49–56.

Holland, Dawn and Jonathan Portes. October 2012. Self-defeating austerity? National Institute Economic Review (222): F4–F10.

Horobin, William. 2019. France’s Villeroy urges fiscal stimulus in Germany. Netherlands Technical Report, Bloomberg

Ilzetzki, Ethan, Enrique G. Mendoza, and Carlos A. Vegh. 2013. How big (small?) are fiscal multipliers? Journal of Monetary Economics 60(2): 239–254.

Imbens, Guido W., and Thomas Lemieux. 2008. Regression discontinuity designs: A guide to practice. Journal of Econometrics 142(2): 615–635.

International Monetary Fund. 2014. World Economic Outlook: Legacies, Clouds, Uncertainties. October.

Kallstrom, John. 2014. Pushing for growth. Masters Thesis, Lund University.

Mohl, Philipp, and Tobias Hagen. 2010. Do EU structural funds promote regional growth? New evidence from various panel data approaches. Regional Science and Urban Economics 40(5): 353–365.

Mohl, Philipp and Tobias Hagen. 2011. Do EU structural funds promote regional employment? Evidence from dynamic panel data models. Working Paper Series, European Central Bank 1403, European Central Bank.

Nakamura, Emi, and Jon Steinsson. 2014. Fiscal stimulus in a monetary union: Evidence from US regions. American Economic Review 104(3): 753–92.

Nickell, Stephen J. 1981. Biases in dynamic models with fixed effects. Econometrica 49(6): 1417–26.

Pellegrini, Guido, Flavia Terribile, Ornella Tarola, Teo Muccigrosso, and Federica Busillo. 2013. Measuring the effects of European Regional Policy on economic growth: A regression discontinuity approach. Papers in Regional Science 92(1): 217–233.

Ramey, Valerie. 2019. Ten years after the financial crisis: What have we learned from the renaissance in fiscal research? Working Paper 25531, forthcoming in Journal of Economic Perspectives, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ramey, Valerie A. 2011. Identifying government spending shocks: It’s all in the timing. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 126(1): 1–50.

Raposo, Ines Goncalves, and Alexander Lehmann. 2019. Equity finance and capital market integration in Europe. Policy Contribution 3, Bruegel.

Sala-i-Martin, Xavier X. 1996. Regional cohesion: Evidence and theories of regional growth and convergence. European Economic Review 40(6): 1325–1352.

Serrato, Juan Carlos Suarez, and Philippe Wingender. 2016. Estimating Fiscal Local Multipliers. NBER Working Paper 22425.

Thissen, Mark, Frank van Oort, and Dario Diodato. 2013. Integration and convergence in regional Europe: European regional trade flows from 2000 to 2010. European Regional Science Association: ERSA conference papers.

Vermeulen, Philip, Daniel A. Dias, Maarten Dossche, Erwan Gautier, Ignacio Hernando, Roberto Sabbatini, and Harald Stahl. 2012. Price setting in the Euro area: Some stylized facts from individual producer price data. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking 44(8): 1631–1650.

Acknowledgements

I am especially grateful to Alan Auerbach for his guidance, encouragement and invaluable feedback on this project. I am also grateful to Barry Eichengreen, Yuriy Gorodnichenko, and Emmanuel Saez for their feedback and helpful advice at different stages of this paper. This project also benefited from discussions with Sasha Becker, Carola Binder, Erik Johnson, John Mondragon, Christina and David Romer, Johannes Wieland, and seminar participants at Berkeley, the Austrian National Bank, and the CBI-IMF-IMFER The Euro at 20 conference. Constructive suggestions by thoughtful reviewers have also significantly strengthened this paper. I am extremely grateful to John Walsh and Mark Thissen for kindly sharing the underlying data, without which this project would not have been possible. I acknowledge financial support from Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia and the Robert D. Burch Center for Tax Policy and Public Finance. The views expressed in this paper are my own and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management. All remaining errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Tables

1.1 Robustness checks

Appendix 2: Figures

Sources: European Commission—DG Regio, Eurostat, Thissen et al. (2013), author calculations

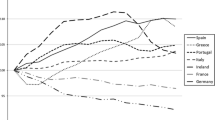

GDP growth versus trade-weighted expenditure spillover shock: 2001–2011.

Appendix 3: Fuzzy Regression Discontinuity

Several papers have exploited the discrete jump in probability of receiving Objective 1 transfers in a regression discontinuity design (Kallstrom 2014; Pellegrini et al. 2013), though the most cited reference in this line of literature (and also the first one to really explore this design) remains Becker et al. (2010). As summarized earlier, the authors use a binary treatment variable (whether or not a NUTS 2 region was eligible for Objective 1 transfers) to estimate the local average treatment effect of structural funds on average GDP growth and employment within a programming period. The analysis below aims at mirroring the strategy used by Becker et al. (2010), but addressing a couple of its limitations which the data used in the panel instrumental variables exercise above enables me to do. In particular, instead of binary treatment, I use a continuous treatment variable (actual expenditures received), that is furthermore instrumented as in the panel IV above by corresponding commitments; the same rationale for instrumenting applies as before (endogeneity in expenditures with respect to aggregate demand conditions and measurement error). In addition, although the nature of the quasi-experimental design does arise from a discontinuity in eligibility for Objective 1 funds, I use the total amount of funds transferred to regions (including Objective 2 funds) as my treatment variable; the reason behind this choice is that using merely Objective 1 transfers implicitly attributes 0 valued transfers to most regions on the right-side of the discontinuity threshold, thus exacerbating the true treatment discontinuityFootnote 17 and underestimating any existing treatment effect. As in robustness Table 12, I find some evidence of weaker treatment effects in the 2007–2013 period, due likely to the particular choice of fiscal shock identification in levels—a necessary evil of the regression discontinuity criterion.

Although I have data on annual commitments and expenditures by NUTS 2 region,Footnote 18 the treatment assignment variable (running variable in the regression discontinuity created by the threshold of eligibility for Obj.1 funds, i.e., reference-period GDP per capita) is unique per programming period. Thus, in what follows I estimate the local average treatment effect of Obj.1 fund eligibility separately for each programming period (the samples can of course also be pooled, treating each region as a separate region-programming period unit).

From the graphs below, it is apparent that we are dealing with a fuzzy discontinuity, since there are a few Obj.1 regions above the eligibility threshold. However, most regions receiving positive funds above that threshold are Obj.2 regions. Thus, a simple binary treatment regression discontinuity local average treatment effect estimation would vastly underestimate any actual effects, by imputing zero treatment on Obj.2 regions which actually get some federal funding (albeit significantly smaller than the Obj.1 sample on average). In addition, it is worthwhile noting that several Obj.1 regions are allocated funds at per capita levels comparable to Obj.2 regions—in other words, Obj.1 treatment is highly heterogeneous, and comparisons should be made between those with high levels of transfers and regular Obj.2 regions, conditional on similar reference-period GDP per capita, rather than all regions within a given band of the threshold (Figs. 8, 9).

For the “normal” 2000–2006 programming period, we can see the graphical evidence in Fig. 12 in support of a regression discontinuity design below: commitments (per capita and as a share of initial GDP) show a discontinuity and change in slope (interaction effect) at the eligibility threshold with respect to the assignment variable (reference-period GDP per capita). However, when looking at the outcome variable (average real GDP growth), it is difficult to see such a discontinuity—if anything, my evidence goes in the opposite direction from that found by Becker et al. (2010), in that growth outcomes are slightly lower immediately before the threshold relative to those immediately after. This is apparent using linear fits or 5th order asymmetric polynomials on both sides of the threshold. Note in this graphical evidence we are using commitments, rather than expenditures as treatment, since the latter can be driven by local demand conditions (this was in fact the core motivation underlying my earlier broad sample IV estimation). Graphically, however, expenditures and commitments behave alike with respect to the assignment variable (Figs. 10, 11, 12, 13).

Since I have a continuous treatment variable with non-compliers to the treatment assignment rule (fuzzy design), the RD naturally has to be estimated in two stages. In addition to using a binary indicator of whether a region is above or below the threshold (the typical exclusive instrument for treatment in this setup), I add the respective commitments series as an additional instrument. In particular, the second stage specification is

where in the first stage I estimate

\(g\left( F_{it}\right)\) and \(f\left( F_{it}\right)\), functions of the forcing variable \(F_{it}\), are approximated by asymmetric polynomials on each side of the threshold, including interaction terms. In what follows, I treat the data as a pooled cross section for each programming period, although year and country fixed effects are used, just as for the panel estimates above.Footnote 19 I estimate the treatment assignment function in the first stage via 3rd/5th degree asymmetric polynomial approximation of the total funds spent in a given programming period around the threshold.Footnote 20 The outcome variable then on the second stage is the annual GDP per capita growth rate over the respective years.

While I find a large LATE consistent with the IV results above for the 2000–2006 period [consistent with the findings of Becker et al. (2010)], the same is not true of the 2007–2013 period. Looking at the yearly cross section of GDP versus forcing (or assignment) variable, we see that the 2000–2006 negative correlation pattern persists through 2007, starts shifting toward no correlation during 2008–2009 as most regions in the Eurozone head toward negative growth territory, and is inverted in 2010 and 2011, as regions in Greece, Portugal and Spain remain at negative growth rates (trapped at the epicenter of the then emerging sovereign debt crisis), while other countries start to recover from the 2008 recession. In other words, there were asymmetric macroeconomic shocks at the country level affecting these regions over time which blur the normally observed positive correlation between the forcing variable and GDP growth.Footnote 21 Furthermore, some of the reasons related to the particular interference of the recent financial and sovereign debt crisis with the allocation mechanisms of these transfers may also contribute to explain the unusual results. This contrasts with the stronger-in-recession measured multipliers in the panel IV estimation core section of this paper using year-on-year changes in expenditures as the fiscal shock of interest, in line with the cross-country findings of Auerbach and Gorodnichenko (2012).

It is worthwhile noting that, in contrast to the earlier panel IV, the coefficient estimates on Table 16 cannot be directly interpreted as fiscal multipliers. Rather, they reflect an average response over the medium-run (the length of a programming period, 6–7 years) to ongoing treatment levels. Recall the independent variable of interest in the RD is the level of transfers (as a ratio to population or GDP), rather than a change in levels, or a shock per se whose propagation can be estimated in subsequent years.