Abstract

The 2016 referendum vote to leave the European Union (EU) brought about significant change in the policy and strategy of the Conservative Party. Despite David Cameron’s resignation, these dramatic shifts have not been matched by changes in personnel or dominant faction as MPs who voted Remain continue to outnumber those who voted Leave at the top echelons of the party. 140 Conservative MPs, many with a record of rebellion on EU issues, voted Leave, but among Remain-voting MPs were many ‘reluctant Remainers’. All except Ken Clarke subsequently voted for the Bill triggering Article 50 but, in a party long divided over the EU issue, the institutional support mechanisms underpinning policy change are fragile. Conservative divisions have also changed as soft and hard Brexiteers disagree over the withdrawal process and the UK’s future relationship with the EU. With the Conservatives now a minority government, parliament offers various ways in which MPs can register dissent and influence policy, from amending core Brexit legislation to supporting critical Select Committee reports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The 2016 referendum vote to leave the European Union (EU) brought about significant changes to the leadership and policy of the Conservative Party. David Cameron’s government advocated a vote to Remain as did most Conservative MPs, although ministers were permitted to campaign to Leave and the party organisation remained neutral. Cameron had developed a soft Eurosceptic position that supported membership of a reformed EU and culminated in a renegotiation that set out the UK’s ‘special status’. His pledge of an in–out referendum had been shaped by party management concerns, with hard Eurosceptic MPs rebelling frequently, and the rise of the UK Independence Party (UKIP). However, intra-party divisions contributed to the Leave vote as Conservative supporters received mixed messages from their party (Curtice 2017).

Cameron resigned after the referendum and was replaced by Theresa May who, despite supporting Remain, adopted a Brexit policy hitherto favoured by a minority of Conservative MPs. May called a general election in 2017 which she fought primarily on the Brexit issue but lost seats and formed a minority government. Despite these abrupt changes to policy and electoral strategy, Brexit has not brought similarly extensive change to personnel in government where hard Eurosceptics are outnumbered by ministers who voted Remain.

This article examines the extent to which Brexit is driving change within a party whose leadership and dominant factions had long supported membership of a reformed EU and in which hard Eurosceptics had been a minority largely confined to the backbenches. It assesses the extent to which policy, leadership and personnel have changed since the EU referendum, and then concludes by exploring the opportunities that parliament provides for Remain and Leave MPs to shape the agenda and influence policy.

Party change may result from changes within the party itself, notably a change of leader or dominant faction, or from external developments such as electoral defeat, shifts in the positions of rival parties, the emergence of niche parties, and changes in public opinion (Harmel and Janda 1994; Budge et al. 2010). In his study of change in the Conservative Party, Bale (2012) finds a complex pattern in which leaders and, to a lesser extent, factions may drive policy change but external developments create significant pressures for change. Societal and economical changes, plus international changes such as the end of Empire and European integration, are slow burners and parties adapt gradually. Here, party change is bolstered when championed by the leader and prevailing ideological faction, as when One Nation Conservatives Harold Macmillan and Edward Heath put membership of the European Economic Community at the heart of their modernisation projects.

Post-Brexit change in the Conservative Party is an unusual example given the source of party change (a discretionary referendum called by a leader confident of winning it), its sudden and extensive nature, and the mismatch between major policy change and limited change to leadership, personnel and factional dominance. This lack of congruence means that the government’s position on Brexit lacks the strong institutional underpinnings within the party which are present when a new leader and dominant faction drive change. Furthermore, the referendum has extended rather than ended Conservative divisions on the EU issue. Some Remain MPs are putting pressure on the government to pursue a softer Brexit, while a group of Leave MPs push for a hard Brexit. The EU issue is thus set to dominate and diminish yet another Conservative premiership.

Conservative MPs and the EU referendum

This article uses a dataset created by the authors to establish the positions on the EU issue and referendum of the 330 Conservative MPs in office on 23 June 2016.Footnote 1 It includes data on how each MP voted in the referendum (see below for details), their parliamentary voting record on EU issues, their positions on other key issues (e.g. immigration and same-sex marriage), whether they held or had held government office, the estimated Leave vote in each MP’s constituency (Hanretty 2017), plus their year of birth and when they entered parliament.

According to the dataset, a majority of Conservative MPs (187 of 330) voted Remain but a substantial minority (140) voted Leave (see Table 1). These figures differ slightly from those of Heppell et al. (2017, p. 9) who report 172 Remain, 144 Leave and 14 undisclosed, and Moore (2017, p. 10) with 189 Remain, 135 Leave and 6 undisclosed. It is unclear where these discrepancies arise as the authors do not provide a list of MPs. The BBC News (2016) figures of 185 Remain, 138 Leave and 7 undisclosed are closer to ours, but do not record positions for four MPs who disclosed their preference on referendum day or shortly after: Eleanor Laing and Pauline Latham voted Leave; Huw Merriman and Anne Milton voted Remain. This leaves three whose positions are unknown. Tracey Crouch who was on maternity leave then announced that she would not reveal her vote, while Iain Liddell Grainger cited uncertainty about the future of the Hinkley Point nuclear power station in his constituency. Jesse Norman (2016), a biographer of Edmund Burke, argued that as referendums were not acts of representative democracy, MPs should not disclose their position.

In their studies of how Conservative MPs voted in the referendum, neither Heppell et al. (2017) nor Moore (2017) directly test the effect of earlier Eurosceptic positions on MPs’ voting decisions. Heppell et al. do show that Euroscepticism was more prevalent in the Conservative Party, but their differentiation between ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ Eurosceptics is based upon a 2011 parliamentary vote on an EU referendum (Heppell 2013). However, as explained below, it is problematic to assume that all 81 who supported this motion were Brexiteers or that this represented the totality of hard Eurosceptic opinion.

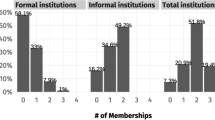

The policy preferences of MPs can be ascertained in various ways, including membership of groups, parliamentary votes and public statements.Footnote 2 Each has some utility in determining Conservative MPs’ positions on European integration, but also limitations. All are shaped by competing motivations of policy, office and votes (Moore 2017) and record the behaviour rather than simply the preferences of MPs. Are MPs, for example, willing to rebel or even disclose their views?

Membership of Eurosceptic groups shows aggregate support for positions on European integration but may not reveal the preferences of individual MPs. No formal membership list exists for the influential Fresh Start Project which attracted support from around 100 MPs and proposed a fundamental renegotiation of the UK’s relationship with the EU (Fresh Start Project 2012). The Conservatives for Britain group was established in June 2015 to monitor Cameron’s renegotiation and prepare for a Leave campaign (Baker 2015). It too claimed support from over 100 MPs. Some 100 Conservative MPs also wrote to Cameron demanding legislation on an EU referendum (Conservative Home 2012), and a parliamentary veto on EU legislation (Daily Telegraph 2014), but the signatories were not named.

Parliamentary votes

Under the 2010–2015 Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition, 49 votes on EU issues saw a Conservative rebellion and a total of 103 Conservative MPs rebelled at least once. The largest ever Conservative rebellion on European integration occurred in October 2011 when 81 MPs defied a three-line whip to support David Nuttall’s motion on an EU referendum. In May 2013, Cameron took the unusual step of granting backbenchers a free vote on an amendment to the Queen’s Speech regretting the absence of a referendum Bill (ministers were required to abstain). A total of 116 Conservative MPs supported it. In 2015–2016, 57 Conservatives rebelled across 15 divisions on EU issues, the most significant being when 37 voted with opposition parties to defeat the government and extend the referendum campaign purdah period.

Parliamentary votes indicate the extent of party cohesion but may not reflect the sincere beliefs of individual MPs (Hug 2013). They may instead reflect MPs’ calculations about policy (e.g. those with strongly held views are more likely to rebel), office (e.g. ministers and PPSs are obliged to support the government, while some MPs may conclude that rebellion would damage their promotion prospects), and votes (e.g. MPs may wish to signal their Euroscepticism to their constituents or constituency association). Despite high levels of dissent, no minister resigned on the EU issue, although two PPSs resigned so that they could vote for the 2011 referendum motion. Chris Grayling’s threat to resign did prompt Cameron to suspend collective responsibility during the referendum campaign, but ministers still came under pressure to support Remain (Shipman 2016).

Table 2 shows the EU referendum vote of Conservative MPs in office on 23 June 2016 in relation to their parliamentary activity and office status. 93 had previously rebelled on at least one parliamentary vote on EU issues. Most, but not all, voted Leave, with the more rebellious being more likely to do so. A majority who voted for the 2011 referendum motion and the 2013 Queen’s Speech ‘regret’ motion voted Leave. However, one in five of those who rebelled and a similar proportion of those who supported the 2011 motion voted Remain. This suggests that Cameron had some success in persuading Eurosceptics to support his position. However, the number who voted Leave exceeds the number who had rebelled on an EU issue. The addition of Leave-supporting ministers does not explain the increase, particularly as 20 rebels voted Remain. This suggests that some Eurosceptic MPs were reluctant to dissent in parliament and that Cameron failed to persuade all these loyalists to support him in the referendum.

Free movement, immigration and sovereignty were key issues in the referendum campaign. The 2013–2014 Immigration Bill saw two indicators of the strength of feeling on them. 76 Conservatives voted for Dominic Raab’s amendment which would have made it mandatory to deport non-UK citizens convicted of a crime carrying a prison sentence of more than a year unless they faced the threat of torture or death, regardless of the right to family life under the European Convention on Human Rights. Backbenchers were given a free vote and frontbenchers required to abstain. An amendment by Nigel Mills which would have reinstated restrictions on the entry into the UK of Bulgarian and Romanian citizens was signed by 57 Conservatives but not voted upon. Most supporters of the amendments voted Leave.

We test the importance of Eurosceptic parliamentary activity for Conservative MPs’ positions in the EU referendum using regression analyses. The dependent variable is coded 1 for a Leave vote and 0 for Remain. As this is a binary-dependent variable, we estimate logistic regression models, which predict the likelihood of falling into one category or another (in this case, Leave or Remain). We control for other motivations that an MP may have faced. We include Hanretty’s (2017) estimates of the Leave vote in each constituency to control for MPs taking account of constituency views in their voting decisions. We include the year in which each MP first entered the House of Commons to assess how far more recent entrants tend to be more Eurosceptic. We also estimate the effects of holding government office at either ministerial or PPS level at various time points. The data include all Conservative MPs who were present in the 2010–2015 Parliament and were still MPs in 2016. Table 3 shows the results of three models. Model 1 shows that the more an MP rebelled on EU issues between 2010 and 2016, the more likely they were to vote Leave. Translating these coefficients into changes in predicted probabilitiesFootnote 3 shows that the likelihood of voting Leave rises from a 25% chance for an MP with no rebellions on an EU issue, to an 83% chance if they had rebelled five times and a 99% chance if they had rebelled 10 times. Model 1 also shows that a higher Leave vote in an MP’s constituency and opposition to same sex marriage are associated with a higher likelihood of voting Leave, but these estimates are more uncertain than those of the effect of rebellions on EU-related votes. Holding ministerial office at the time of the referendum is associated with a lower likelihood of voting Leave. These findings are consistent with those of Heppell et al. (2017) and Moore (2017).

Model 2 finds that support for each of three parliamentary votes—the 2011 referendum motion, the 2013 Queen’s Speech ‘regret’ motion and the 2014 Raab amendment—is associated with a higher likelihood of voting Leave. Of the three, the Raab amendment has the largest substantive effect. Finally, model 3 shows that holding ministerial office at any time between 2010 and 2016 reduces the likelihood of voting Leave, but being a PPS at the time of the referendum had no effect. Additional testing showed that being a minister or PPS in the past but not at the time of the referendum did not have a statistically discernible effect, probably because the number of people in this category is too small for a reliable effect to be detected.

Public statements

Under the 2010–2015 coalition government, few Conservative MPs publicly advocated withdrawal. Instead, would-be Brexiteers spoke of fundamental reform. This changed as the referendum neared. Analysis of public statements made by MPs between January and June 2016 casts further light on why some hitherto loyal Conservatives backed Leave, while others with a Eurosceptic track record voted Remain. We collected and coded statements made by Conservative MPs on their referendum position. Most were taken from their websites, but some were taken from their social media sites or statements made to national or local media. Many have since been removed although some are still accessible via the internet archive Wayback Machine (https://archive.org/web/). Statements from ministers were included only when made in a personal capacity. The statements varied from detailed accounts comprising several thousand words, brief statements of a few paragraphs, to tweets stating support for one side. In total, 170 statements by Remain MPs and 132 by Leave MPs were collected. The statements were hand coded, and the coding scheme focused on key themes and policy competences plus positive and negative statements on the EU, Brexit and Cameron’s renegotiation.

The main issues identified in statements by Leave MPs were sovereignty and democracy (mentioned by 101), international trade (72), control of immigration and borders (69) and the costs of EU membership and economic benefits of Brexit (63). There is not scope here to explore these statements in depth. However, it is notable that many of the issues raised by Leave MPs are associated with a hard Brexit. The single market earns some praise but much criticism. Differences among Eurosceptics about the optimal post-Brexit relationship with the EU were apparent before the referendum, but few set out their favoured scenario. Still, there is next to no support for adopting the Swiss or Norwegian models. The failure or limited nature of Cameron’s renegotiations was identified by 69 MPs as a reason for supporting Brexit, although most placed the blame on an EU unwilling to reform rather than on the prime minister.

The statements shed light on how Eurosceptics from a range of positions (Lynch and Whitaker 2013) voted in the referendum. Outright rejectionists sought withdrawal at the earliest opportunity so renegotiation would never be sufficient for them. Maximal revisionists demanded fundamental renegotiation. The centre of gravity in the Conservative Party had already shifted closer to this position so Cameron faced an uphill task in recruiting a sizeable majority of MPs to the Remain camp. Ultimately, he neither asked for, nor was offered, fundamental change so maximal revisionists broke for Leave. The Fresh Start Project (2016) concluded that most of the reforms it sought had either not been attempted or had been only partially achieved and thus advocated Leave. Minimal revisionists supported a limited repatriation of competences and an end to any commitment to ‘ever closer union’. Renegotiation offered them something by confirming the UK’s special status, but also left them disappointed given the failure to repatriate policies. Hence, some previously loyal MPs supported Brexit.

Among Remain MPs, the key issues were the economic benefits of EU membership (mentioned by 114), with single market access and trade deals identified most frequently, and national security (49). The long-term decline of pro-European sentiment in the Conservative Party is apparent, with only 14 MPs making a case based upon British or shared European values. More than half of Remain MPs cited the costs or risks of Brexit, ranging from job losses in the constituency to the difficulties of Brexit negotiations. This mirrors the government’s emphasis on the risks of leaving, but it is revealing that many who highlight these risks have little positive to say about the EU. Others, like ministers Caroline Dinenage, Sam Gyimah and Hugo Swire, state that the UK would be fine outside the EU.

Cameron’s renegotiations were mentioned favourably by 96 Remain MPs. Given that the renegotiations barely featured in the referendum campaign, this owes much to the timing of their statements with many made shortly after the renegotiations concluded. Significantly, 45 Remain MPs expressed disappointment at the limited scope of the renegotiations and/or stressed the importance of further reform. Many of these ‘reluctant Remainers’ described themselves as Eurosceptics and stated that the decision to vote Remain had been difficult or finely balanced. Four statements from MPs with no record of EU rebellion are typical. Mark Lancaster (2016) stated that he would ‘put my personal prejudices to one side, hold my nose and be a reluctant “in” supporter’; Oliver Dowden (2016) had ‘reluctantly accepted the Prime Minister’s argument that we should remain at this stage’, while David Mowat (2016) stated that ‘on balance, I remain a reluctant inner. However, quite frankly, the issues are very close’. Michelle Donelan went further in a statement she has since removed: ‘whilst making this decision I have felt very sick, not just because it is a monumental decision but because I felt like I was betraying who I am and the views that I have always held’. Steve Brine, Alex Chalk, Alan Duncan, James Heappey, Mark Prichard and Amanda Solloway are among those stating that they had been leaning towards Leave. The underlying Euroscepticism of ministers Nick Gibb, Sajid Javid, Robin Walker and Jeremy Wright is also evident.

All Brexiteers now?

The Conservative Party’s relatively smooth transition to Brexit despite most MPs having voted Remain is explained partly by the number of Eurosceptic ‘reluctant Remainers’. Had they switched camp, there would have been majority support for Leave among Conservative MPs. However, most Remain-voting Conservatives also quickly accepted the referendum result and that the government must deliver Brexit. This has not stopped enthusiastic Remainers from expressing concern about the outcome, criticising the Leave campaign, and promising to work for a positive Brexit. The latter could mean prolonged membership of the single market and customs union. The threat of rebellion by Remain Conservatives on a December 2016 Labour motion helped persuade May to issue a White Paper on the government’s approach to Brexit. However, Ken Clarke was the only Conservative to vote against the government’s plan for Brexit and against the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill 2016–2017—which triggered Article 50—at second or third reading.

The façade of unity on the principle of leaving the EU does not then extend to unity on how that end is reached, the timing of it, or the UK’s relationship with the EU thereafter. During the passage of the Article 50 Bill, seven Remain-supporting Conservatives rebelled on a motion requiring a ‘meaningful’ parliamentary vote to approve any deal with the EU. Three rebelled on a vote on protecting the rights of EU nationals residing in the UK. In total, nine Conservatives rebelled on the Bill: Clarke, plus Heidi Allen, Alex Chalk, Tania Mathias, Bob Neill, Claire Perry, Antoinette Sandbach, Anna Soubry and Andrew Tyrie. Six abstained: Alasdair Burt, Dominic Grieve, Nick Herbert, Ben Howlett, Nicky Morgan and George Osborne. Morgan, Osborne, Soubry and Perry had been dismissed in May’s 2016 reshuffle, while Burt stepped down, but he and Perry were reinstated the following year. The Bill passed without amendment or substantial concessions by the government.

Conservative hard Brexiteers have been highly organised in parliament. They used the Backbench Business Committee to secure the 2011 EU referendum debate, kept the pressure on Cameron after his referendum pledge by tabling the 2013 motion regretting the absence of legislation on a referendum in the Queen’s Speech, which in turn persuaded the leadership to throw its weight behind Private Member’s Bills on the issue. Then Eurosceptics forced the government to give ground on the timing of the referendum and the purdah period (Shipman 2016).

After the referendum, Conservatives for Britain was dissolved and the European Research Group relaunched. It includes over 60 MPs who want to leave the single market, customs union and the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, oppose a punitive ‘divorce bill’ and lengthy transition period, and do not fear (indeed, may welcome) the prospect of leaving the EU without a deal (Riley-Smith and Yorke 2016). The group includes Eurosceptic rebels who have mastered the art of using parliamentary procedures to trouble the government. Will these MPs, for whom concessions have rarely proved sufficient, now accept some blurring of their red lines to smooth the way to Brexit? There are also differences among even hard Brexiteers on when to mobilise and on their preferred relationship with the EU, and other Leave-supporting MPs take a more pragmatic approach.

Party change: policy and strategy

The Conservatives held a soft Eurosceptic position from the late 1990s until the 2016 referendum. It supported reform of the EU (e.g. extending the single market), opt-outs or non-participation in core EU policies (e.g. economic and monetary union, some policing and criminal justice measures), the repatriation of some policies, and referendums on new EU treaties. Cameron maintained this position, and that of lowering the salience of the EU issue, but also pledged renegotiation and an in–out referendum. Measures agreed during the renegotiations included an exemption from ‘ever closer union’ and an emergency brake on in-work benefits for EU migrants.

May set out her position in a speech at Lancaster House in January 2017 (May 2017). It includes leaving the single market, ending the free movement of EU nationals and not offering unilateral guarantees on the rights of those currently resident in the UK, ending the jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice in the UK, seeking a bespoke deal, and leaving the EU without a deal if a favourable agreement cannot be reached. However, May also wants the ‘freest possible’ frictionless trade with the EU and a transition period.

Whereas Cameron had downplayed the EU issue in the 2010 and 2015 general elections, Brexit was the dominant issue in the Conservatives’ 2017 campaign and targeting Leave voters was central to the party’s strategy. However, it did not deliver the anticipated rewards. The Conservatives took the lion’s share of UKIP’s 2015 support and gained ground in constituencies with a large Leave vote, yet Labour not only retained much of its Leave-voting support but also made significant gains in constituencies that voted Remain (Heath and Goodwin 2017). This confirmed the emergence of a cosmopolitan versus non-cosmopolitan cleavage, fuelling change in Conservative support as they make gains in areas with older and less-diverse populations but lose seats with higher numbers of middle-class professionals (Jennings and Stoker 2017). Another electoral challenge is that the short-term costs of Brexit and/or leaving without a deal could badly damage the party’s reputation for competence.

Brexit also raises fundamental questions about the Conservatives’ historic identity as the party of the Union and the party of business. The former may come under strain over the future of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic, and whether EU competences are repatriated to Westminster or the devolved institutions. The 13 Scottish Conservative MPs elected in 2017 have their own distinctive Brexit agenda (e.g. on fisheries policy), as do the Democratic Unionist Party. Brexit also risks fracturing the Conservatives’ relationship with business should it, or key sectors such as financial services, regard the costs as too high. Furthermore, Brexit re-opens left–right divisions within the party as ultra-Thatcherites favour a small state, free trade ‘hyperglobalist’ model (Baker et al. 2002), while May (2017) talks of protecting workers’ rights and an interventionist industrial strategy.

Party change: leadership and personnel

May embraced Brexit after the referendum, but she was not the favoured candidate of Leave supporters in the 2016 Conservative leadership election. Table 4 shows declared supporters ahead of the second ballot, based upon data taken from MPs’ statements and lists collated by the media. May had 193 declared supporters, Leadsom 55 and Gove 28. In the second ballot itself, May received a further six votes, Gove 18 more and Leadsom an additional 29. There are significant differences in the support bases of the candidates (see also Jeffery et al. 2017). Only five ministers endorsed Leadsom, with Theresa Villiers the only Cabinet minister, although she was also supported by Boris Johnson and Iain Duncan Smith. May polled well among both backbenchers and, particularly, ministers.

Of the 187 Conservative MPs who voted Remain, at least 150 backed May whereas Leadsom was endorsed by just four. May had some appeal across the EU fault-line with 41 Leave MPs backing her: 29% of MPs who voted Leave supported May and Leavers made up 21% of her support. May had been a rather reluctant Remainer, playing a low-key role in the referendum campaign (Oliver 2016; Shipman 2016) and during the leadership contest then stressed that Brexit and lower migration would be delivered. She was endorsed by Liam Fox after his elimination on the first ballot and by two Cabinet ministers who campaigned for Brexit, Grayling (her campaign manager) and Priti Patel.

Only 51 of the 140 Conservative MPs who voted Leave (36%) publicly endorsed Leadsom, but many of the 30 who did not declare for a candidate are also likely to have voted for her. As the last Eurosceptic standing, Leadsom was the default Leave candidate. She failed to rally sufficient support from Leavers and had little appeal beyond the backbenches. This continues a trend. The EU issue has been important in each Conservative leadership election since 1990 but only in 2001, when Duncan Smith defeated Clarke, has the most Eurosceptic candidate won. Even then, Duncan Smith secured only 24% of votes on the first ballot and had next to no appeal beyond his Eurosceptic base. The 2016 contest was another in which Eurosceptics, despite their increased numbers and parliamentary organisation, could not find a candidate with sufficient appeal (to Eurosceptics and others), experience and campaigning skills. Johnson and Michael Gove had the potential to appeal across the Brexit divide, with the former focusing on sovereignty rather than immigration and suggesting further European cooperation in some areas (Johnson 2016). However, their fallout triggered mutually assured destruction. Leadsom’s limited support and some ill-judged statements prompted her withdrawal from the contest.

Government

There has been no significant increase in the number of Leave-supporting MPs in government since May became prime minister. Indeed, Table 5 shows that the proportion has fallen slightly. These figures should be treated with caution because, as we have seen, all Remain MPs bar Clarke voted to trigger Article 50 and some were ‘reluctant Remainers’. Nonetheless, they illustrate the limited nature of internal change and the fragile foundations of policy change.

In July 2016, May dismissed 13 Cabinet ministers, including Osborne and Morgan. Three prominent Leavers were appointed to lead departments that would play a pivotal role in Brexit: David Davis became Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union, Fox returned to Cabinet as Secretary of State for International Trade, and Johnson was appointed Foreign Secretary. Two junior ministers prominent in the Leave campaign, Leadsom and Patel, were promoted to full Cabinet rank. Overall, however, there has only been a net increase of one Leave-supporter in the Cabinet. Duncan Smith resigned before the referendum, and three Cabinet ministers who campaigned for Brexit—Gove, Villiers and John Whittingdale—lost their jobs in 2016, before Gove returned in the limited reshuffle that followed the 2017 general election.

The number of Leave-supporting junior ministers has fallen, with five of the 12 who backed Brexit departing in 2016. Parliamentary private secretaries are part of the ‘payroll vote’ required to support the government. Even at this first rung of the ladder, the number of Brexiteers has declined and by summer 2017 only 14 of 45 PPSs had voted Leave. Few Eurosceptic backbenchers were promoted under Cameron and May has not ended the imbalance. Of the 81 MPs who voted for the 2011 referendum motion, 17 subsequently reached ministerial office and 12 became PPSs. 35 are still on the backbenches.

May has, however, made strategic appointments by promoting the founders of the Fresh Start Project, Leadsom, George Eustice and Chris Heaton-Harris, plus Steve Baker, founder of Conservatives for Britain then chair of the European Research Group, who became a junior minister in the Department for Exiting the European Union in 2017. Suella Fernandes succeeded Baker as chair of the European Research Group and retained this position despite promotion to PPS. In the whips office, which is critical in enforcing party discipline, the imbalance has been addressed as the number of Leave supporters has risen from one to seven.

The number of hard Eurosceptics ministers may not have increased, but their influence has. They hold lead positions in departments critical to Brexit (e.g. at the Department for Exiting the EU), key positions in others (e.g. Raab’s role at the Ministry of Justice includes EU exit issues), and in departments where Brexit will have far-reaching implications (e.g. Gove and Eustice at the Department for Food, Environment and Rural Affairs). May will hope that, as compromises are made during the Brexit negotiations, Eurosceptic ministers persuade backbenchers that these are a price worth paying. The risk is that they resign and incite hard Eurosceptic rebellion.

Parliamentary party

Following the 2017 general election, the Conservative parliamentary party consists of 170 MPs who voted Remain, 138 who voted Leave and 9 (including five from Scotland) whose referendum vote is undisclosed. Again, caution is required as most who voted Remain are reconciled to Brexit. The post-1979 trend of each Conservative cohort being more Eurosceptic than its predecessor continues (Baker et al. 2002; Heppell et al. 2017). Taking into account seat losses and gains in three 2016 by elections plus the general election, as well as retirements and replacements, there is a net loss of 17 Remain-voting MPs but a net loss of two Leave MPs. 29 MPs who voted Remain stood down or lost their seats, compared to 18 who backed Leave. Among those defeated were Neil Carmichael, chair of the Conservative Group for Europe, plus two MPs from Remain constituencies who had rebelled on the Article 50 Bill, Ben Howlett (Bath) and Tania Mathias (Twickenham). Eurosceptics Peter Lilley and Gerald Howarth retired, while serial rebels David Nuttall and Stewart Jackson were defeated, the latter in the Leave stronghold of Peterborough.

Conservative MPs, Brexit and parliament

The EU issue proved difficult for Cameron and will be still more salient and contested in the 2017–2019 parliamentary session. Additional headaches for May include her failure to win a parliamentary majority or mandate for her vision of Brexit, the contentious nature of the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill 2017–2019 (formerly the ‘Great Repeal Bill’) and other Brexit legislation, the likelihood of concessions being made in negotiations with the EU, the potential for dissent from both hard and soft Brexiteers, and the difficulties in reconciling their differing priorities on sovereignty, immigration, and the single market (Cowley 2017).

Governments try to avoid dissent by restricting the parliamentary time spent on difficult issues, but Brexit will dominate the current parliament. The European Union (Withdrawal) Bill which will convert all EU law into UK law on exit proposes wide-ranging powers for ministers (‘Henry VIII’ clauses) to deal with ‘deficiencies’ in this law and implement a withdrawal agreement by using secondary legislation, over which parliament has little say. Other strategies used by Cameron to manage divisions, notably lowering the salience of the issue, deferring decisions and pledging a referendum (Lynch and Whitaker 2013), are no longer available. The EU referendum has also changed the incentives for opposition parties and backbench MPs. Before it, Labour leaders recognised that its voters and, to a lesser extent, MPs were divided on the issue and saw little electoral return from raising its salience. However, Labour won over both Remain and Leave voters in 2017 and can improve its prospects of office by exploiting Conservative divisions. Engaging with EU issues was a minority pastime for backbench MPs in the 2010–2015 parliament, with Conservative Eurosceptics responsible for many of the legislative amendments, Private Member’s Bills, parliamentary questions and contributions to EU debates. However, Brexit changes the incentives for MPs who may now have added motivation to signal their position to their constituents and stronger policy motivations. The latter has produced cross-party cooperation in, for example, the All-Party Parliamentary Group on EU Relations which favours continued membership of the customs union.

MPs can influence policy in various ways (Russell and Cowley 2016). Amendments to government legislation are foremost among them. No Conservatives voted against the second reading of the European Union (Withdrawal) Bill. However, led by Grieve, 17 Conservatives favouring a soft Brexit immediately tabled a series of amendments aimed at limiting Henry VIII powers, requiring the Brexit deal to be approved by statute, and transferring the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights into UK law. The amendments were supported by Labour and Liberal Democrat backbenchers. Rebellions smaller than those seen on many EU issues since 2010 could defeat the government, but this prospect may persuade dissenters to fall in line if they can extract some concessions.

Select Committees raise the profile of issues and shape the agenda. Having rarely considered EU issues before the referendum, many are now carrying out inquiries on Brexit-related issues. The Select Committee on Exiting the EU saw pronounced divisions in 2016–2017 when Eurosceptic Conservatives tabled amendments, forced divisions and walked out of an inquiry into the government’s negotiating objectives. Five Conservatives voted against the Committee’s third report of 2016–2017 because of its warning about ‘no deal’, but two voted in favour. Other select committees have been consensual, as is their norm. Despite all six Conservative members of the 2016–2017 Select Committee on International Trade supporting Leave, it agreed unanimously a report (2017) which recommended ruling out ‘no deal’ and considering the implications of re-joining the European Free Trade Association. The Select Committee on Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (2017) recommended that leaving Euratom be delayed or a transitional deal agreed. The government cannot, then, count on the unconditional support of Leavers, who can use parliamentary avenues other than rebellion to register their concerns.

Debates scheduled by the Backbench Business Committee and in Westminster Hall allow backbench MPs to raise issues. The former has held debates on the impact of Brexit on financial services and fisheries, while differing Conservative positions on Euratom were evident during a July 2017 Westminster Hall debate.

Conclusions

Change is often difficult for political parties, who take time to adapt to new scenarios. The Conservatives have reversed their position on European integration three times since the 1950s: applying to join the EEC in 1961 having originally ruled out entry; developing a soft Eurosceptic position from the late 1980s which saw the former the ‘party of Europe’ become less enthusiastic about the EU than the Labour Party; and supporting Brexit after the EU referendum in which the government campaigned to Remain. The first two changes were gradual but brought intense debate, dissent and defection. The sudden, far-reaching nature of the policy and strategic change forced by the EU referendum denies the Conservatives time and space to come to terms with the realities of Brexit. Adaptation to change may be surer when a new leader and dominant faction provide internal impetus. However, the switch of policy on Brexit is not because a coherent Eurosceptic faction has taken the reins. Instead, MPs who backed Remain are more numerous in government although Leave supporters do hold crucial positions and May was a somewhat reluctant Remainer.

The Leave vote raises the salience of, and inter-party and intra-party contestation on, the most divisive issue in Conservative politics of recent years. Parliament provides multiple opportunities for hard Brexiteers, many with a history of rebellion, and soft Brexiteers, smaller in number but now motivated, to register their dissent and make life difficult for the government. May had hoped that the 2017 general election would deliver a large parliamentary majority and mandate for her route map to Brexit. Instead it has made the most difficult single challenge facing any government since the end of World War 2 still more formidable.

Notes

The dataset is available at https://www.parlbrexit.co.uk.

Surveys provide evidence of MPs’ preferences on the EU issue (e.g. Cowley 2017) but gauging the preferences of individual MPs is tricky if responses are anonymous and response rates low. Early Day Motions may also be examined, but MPs on the government payroll vote do not sign them and some others chose not to.

For the calculation of these predicted probabilities, all other variables were held at their mean or—in the case of dummy variables—modal values.

References

Baker, D., A. Gamble, and D. Seawright. 2002. Sovereign nations and global markets: Modern British Conservatism and hyperglobalism. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 4 (3): 399–428.

Baker, S. 2015. Conservatives will stand up for Britain if the EU lets us down. Daily Telegraph, 6 June, www.telegraph.co.uk/news/newstopics/eureferendum/11657169/Conservatives-will-stand-up-for-Britain-if-the-EU-lets-us-down.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Bale, T. 2012. The Conservatives since 1945. The drivers of party change. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

BBC News. 2016. EU vote: where the Cabinet and other MPs stand. 22 June, www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-politics-eu-referendum-35616946. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Budge, I., L. Ezrow, and M.D. McDonald. 2010. Ideology, party factionalism and policy change: An integrated dynamic theory. British Journal of Political Science 40 (4): 781–804.

Curtice, J. 2017. Why Leave won the UK’s EU referendum. Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (S1): 19–37.

Conservative Home. 2012. 100 Tory MPs call for Cameron to prepare legislation for EU referendum. 28 June, www.conservativehome.com/thetorydiary/2012/06/100-tory-mps-call-for-cameron-to-prepare-legislation-for-eu-referendum.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Cowley, P. 2017 EU referendum: one year on MPs. UK in a Changing Europe, 26 June. http://ukandeu.ac.uk/eu-referendum-one-year-on-mps/. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Daily Telegraph. 2014. EU veto: The Tory MPs letter to David Cameron. 11 January. www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/conservative/10566124/EU-veto-The-Tory-MPs-letter-to-David-Cameron.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Dowden, O. 2016. Oliver’s column in My News: May 2016. www.oliverdowden.com/news/olivers-column-my-news-may-2016. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Fresh Start Project. 2012. Options for Change Green Paper. Renegotiating the UK’s Relationship with the EU. www.eufreshstart.org/downloads/fullgreenpaper.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Fresh Start Project. 2016. Is the ‘UK Settlement’ an EU fresh start? www.eufreshstart.co.uk/FSP%20UK%20Settlement%20Statement.pdf. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Hanretty, C. 2017. Areal interpolation and the UK’s referendum on EU membership. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties.. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457289.2017.1287081.

Harmel, R., and K. Janda. 1994. An integrated theory of party goals and party change. Journal of Theoretical Politics 63 (3): 259–287.

Heath, O., and M. Goodwin. 2017. The 2017 general election, Brexit and the return to two-party politics: An aggregate-level analysis of the result. Political Quarterly 88 (3): 345–358.

Heppell, T. 2013. Cameron and liberal conservatism: Attitudes within the parliamentary Conservative Party and Conservative ministers. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 15 (3): 340–361.

Heppell, T., A. Crines, and D. Jeffery. 2017. The United Kingdom referendum on European Union membership: The voting of Conservative parliamentarians. Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (4): 762–778.

Hug, S. 2013. Parliamentary voting. In Party governance and party democracy, ed. W.C. Muller, and H.M. Narud, 137–158. New York: Springer.

Jeffery, D., T. Heppell, R. Hayton, and A. Crines. 2017. The Conservative Party leadership election of 2016: an analysis of the voting motivations of Conservative parliamentarians. Parliamentary Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx027.

Jennings, W., and G. Stoker. 2017. Tilting towards the cosmopolitan axis? Political change in England and the 2017 general election. Political Quarterly 88 (3): 359–369.

Johnson, B. 2016. I cannot stress too much that Britain is part of Europe and always will be. Daily Telegraph, 26 June. www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/06/26/i-cannot-stress-too-much-that-britain-is-part-of-europe–and-alw/. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Lancaster, M. 2016. EU referendum. https://web.archive.org/web/20170409180147, https://www.lancaster4mk.com/home/eu-referendum/489. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Lynch, P., and R. Whitaker. 2013. Where there is discord, can they bring harmony? Managing intra-party dissent on European integration in the Conservative Party. British Journal of Politics and International Relations 15 (3): 317–339.

May, T. 2017. The Government’s negotiating objectives for exiting the EU. Speech at Lancaster House, London, 17 January. www.gov.uk/government/speeches/the-governments-negotiating-objectives-for-exiting-the-eu-pm-speech. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Moore, L. 2017. Policy, office and votes: Conservative MPs and the Brexit referendum. Parliamentary Affairs. https://doi.org/10.1093/pa/gsx010.

Mowat, D. 2016. It’s over to EU now. 26 February. https://web.archive.org/web/20170106071929/HTTP://WWW.DAVIDMOWAT.ORG.UK/IT_S_OVER_TO_EU_NOW. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Norman, J. 2016. People need independent advice and information in EU debate. The Times, 24 March.

Oliver, C. 2016. Unleashing demons. The inside story of Brexit. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

Riley-Smith, B. and Yorke, H. 2016. Heavyweight Brexiteers among 60 Tory MPs to demand clean break from EU. Daily Telegraph, 19 November, www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/11/19/heavyweight-brexiteers-go-public-as-60-tory-mps-demand-clean-bre/. Accessed 28 Aug 2017.

Russell, M., and P. Cowley. 2016. The policy power of the Westminster parliament: The ‘parliamentary state’ and empirical evidence. Governance 29 (1): 121–137.

Select Committee on Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy. 2017. Leaving the EU: priorities for energy and climate change policy. 4th Report, 2016–2017, HC 909.

Select Committee on Exiting the EU. 2017. The Government’s negotiating objectives: the White Paper. 3rd Report, 2016–2017, HC 1125.

Select Committee on International Trade. 2017. UK trade options beyond 2019. 1st Report, 2016–2017, HC 817.

Shipman, T. 2016. All out war. The full story of how Brexit sank Britain’s Political Class. London: William Collins.

Acknowledgements

The support of the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) is gratefully acknowledged (Grant Number ES/R000646/1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lynch, P., Whitaker, R. All Brexiteers now? Brexit, the Conservatives and party change. Br Polit 13, 31–47 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-017-0064-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41293-017-0064-6