Abstract

Adequately funding occupational pension funds is a major concern for society in general and individual contributors in particular. The low returns accompanied with high volatility in capital markets have put many funds in distress. While the basic contributions are mostly defined by the state, the fund’s situation may require additional contributions from the insureds or may allow the distribution of surpluses. In this paper, we focus on the accumulation phase of a defined contribution plan in Switzerland with minimum returns and annual solvency targets in terms of an assets-to-liabilities funding ratio. From the viewpoint of the pension fund, we evaluate the outcome of selected funding mechanisms on the solvency situation. Taking the perspective of the contributors, we analyse the payoff and the utility. Combining both prospects, we discuss the boundary values that trigger the various participation mechanisms and their impact. We find that remediation measures, while stabilising the fund, yield a higher volatility in the insureds contributions. Further, surplus distributions lower the relative payoff utility of the funds members and increase the frequency of remediation measures. Overall, insureds and pension funds will profit from a cautious surplus distribution policy that focuses on keeping the stability high and lowers the volatility of the result.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See OECD (2015b).

See OECD (2015a).

See Credit Suisse (2014).

See, e.g. Maas et al. (2015).

See http://www.bsv.admin.ch/altersvorsorge_2020, September 2016.

See Swisscanto (2015).

Contributors changing their employer must change to the pension linked to the new company. Thereby, the assets are transferred, whereas, e.g. potential remediation measures to improve the overall state of the pension fund remain with the previous institution. Exceptions may apply, though, in the case of partial liquidation of the fund (see BVG (2015), Art. 53).

Sharpe (1976).

Black (1976).

O’Brien (1986).

Bacinello (1988).

Dufresne (1989).

Cairns et al. (2006).

Berdin and Gründl (2015).

Schmeiser and Wagner (2014).

Eling and Kiesenbauer (2013).

Alestalo and Puttonen (2006).

Ghilarducci (2010).

Braun et al. (2011).

Broeders et al. (2016).

Chen and Clever (2015).

Gerber and Shiu (2003).

Avanzi et al. (2016).

Albrecher et al. (2016).

Bischofberger and Walser (2011).

Eling (2012).

UBS (2014).

Cosandey (2014).

Eling and Holder (2013).

Broeders et al. (2011).

BVV2 (2016), Art. 44.

BVG (2015), Art. 8.

BVG (2015), Art. 16.

Björk (2004).

Gerber and Shiu (2003).

In contrast to life insurance companies, regulations such as Solvency II and the Swiss Solvency Test (SST) do not apply to Swiss pension funds. The reason why a transfer of these regulations has not been performed yet can be found in the differences between funds and insurers. In contrast to insurance companies, gains and losses are distributed among the members. Additionally, the contractual relationship between the policyholder and the pension fund is quite rigid. For example, employees are automatically affiliated in the pension plan connected to the employer. Due to these characteristics, a temporary phase of underfunding can be dealt with. Pension funds stay in business and pursue their investment strategies even when they are underfunded. Also, it is the decision of the board of the fund if, and to what extent, remediation measures and surplus payments are to be made. This stands in strong contrast to life insurance companies regulated by market authorities that require strict solvency calculations and adequate capitalisation on a year-to-year basis. While there have been efforts to suggest regulations comparable to Solvency II and the SST for pension funds (see, e.g. Schweizerische Kammer der Pensionskassen-Experten 2012; Braun et al. 2011), there are currently no regulations with respect to this.

BVG (2015), Art. 65d.

Note that, in practice, the use of the UF1 method is more common among Swiss pension funds. Furthermore, it is the board of the fund that ultimately decides on when charging remediation measures as well as on their amount.

BVG (2015), Art. 68a.

BVV2 (2016), Art. 48e.

This can be compared with the dividend distribution analysed in Avanzi et al. (2016).

See, e.g. Avanzi and Purcal (2014).

This corresponds to the historical salary changes also found in the adaptations of the BVV2 salary boundaries.

BVV2 (2016), Art. 5.

In our analysis, we do not differentiate between the sources of the contributions, but we focus on the total payoff at time T.

BVV2 (2016), Art. 12.

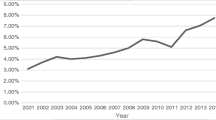

The composition of the index is 60 per cent bonds and 40 per cent equities, with about 40 per cent of the investments made in foreign currencies. For further information, see https://www.group.pictet/corporate/en/home/institutional_investors/lpp_indices/lpp2000.html, September 2016.

We chose to use annualised values based on the monthly observations to have a larger statistical basis (192 observations). The annualised expected return is calculated from the monthly expected return by multiplying by 12. The corresponding volatility is obtained from multiplication by \(\sqrt{12}\). For comparison, when calculating the performance on the base of the only 16 annual data points, we find that the expected return remains unchanged and yields 3 per cent, while the volatility is about 2 per cent higher in the considered period.

In our base case, bonuses can only be distributed if the funding ratio exceeds 110 per cent, i.e. when reserves of 10 per cent on top of the value of the liabilities are accumulated. This reference scenario corresponds to the target values mostly observed in practice (5–10 per cent). In our sensitivity analysis, we vary \(F^{\text {L}} = 110\) per cent through very low and high values ranging from 102 to 118 per cent corresponding to reserves of 2–18 per cent of the liabilities (see Table 3).

FZG (2016), Art. 23.

BVG (2015), Art. 15.

In the Swiss system, a commission regularly decides about changes of \(r_{\text {PL}}\). For this, they take the market conditions into account by using a rolling average of government bonds as a benchmark. We mirror this process in our analysis by adjusting the guaranteed interest rate \(r_{\text {PL}}\) with a delay of two years at a fixed ratio of \(r_{\text {PL}} / \mu _{B}\).

Godwin et al. (1996).

Poterba et al. (2007).

Vigna and Haberman (2001).

References

Albrecher, H., Embrechts, P., Filipović, D., Harrison, G.W., Koch, P., Loisel, S., Vanini, P. and Wagner, J. (2016) ‘Old-age provision: Past, present, future’, European Actuarial Journal 6: 287–306.

Alestalo, N. and Puttonen, V. (2006) ‘Asset allocation in finnish pension funds’, Journal of Pension Economics and Finance, 5(01): 27–44.

Avanzi, B., Henriksen, L.F.B. and Wong, B. (2016) On the distribution of the excedents of funds with assets and liabilities in presence of solvency and recovery requirements, Working Paper, from http://ssrn.com/abstract=2824887.

Avanzi, B. and Purcal, S. (2014) ‘Annuitisation and cross-subsidies in a two-tiered retirement saving system’, Annals of Actuarial Science, 8(2): 234–252.

Bacinello, A.R. (1988) ‘A stochastic simulation procedure for pension schemes’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 7(3): 153–161.

Berdin, E. and Gründl, H. (2015) ‘The effects of a low interest rate environment on life insurers’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice, 40(3): 385–415.

Bischofberger, A. and Walser, R. (2011) ‘Altersvorsorge auf dem Prüfstand - Ein Debakel als Chance’, Avenir Suisse Policy Brief, 1.

Björk, T. (2004) Arbitrage Theory in Continuous Time. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Black, F. (1976) ‘The investment policy spectrum: Individuals, endowment funds and pension funds’, Financial Analysis Journal, 32(1): 23–31.

Braun, A., Rymaszewski, P. and Schmeiser, H. (2011) ‘A traffic light approach to solvency measurement of Swiss occupational pension funds’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice, 36(2): 254–282.

Brent, R.P. (1974) ‘Algorithms for minimization without derivatives’, IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19(5): 632–633.

Broeders, D., Chen, A. and Koos B. (2011) ‘A utility-based comparison of pension funds and life insurance companies under regulatory constraints’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 49(1): 1–10.

Broeders, D., Chen, D., Minderhoud, P. and Schudel, W. (2016) Pension funds herding, DNB Working Paper No. 503, Amsterdam: De Nederlandsche Bank.

BVG ’Bundesgesetz über die berufliche Alters-, Hinterlassenen- und Invalidenvorsorge’, from https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19820152/index.html, accessed 1 January 2015.

BVV2 ’Verordnung über die berufliche Alters-, Hinterlassenen- und Invalidenvorsorge’, from https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19840067/index.html, accessed 1 April 2016.

Cairns, A.J., Blake, D. and Dowd, K. (2006) ‘Stochastic lifestyling: Optimal dynamic asset allocation for defined contribution pension plans’, Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 30(5): 843–877.

Chen, A. and Clever, S. (2015) ‘Optimal supervisory rules for pension funds under diverse pension security mechanisms’, European Actuarial Journal, 5(1): 29–53.

Cosandey, J. (2014) Generationenungerechtigkeit überwinden.

Credit Suisse Economic Research (2014) Schweizer Pensionskassen 2014: Perspektiven in der Demografie und im Anlagemanagement, technical report.

Dufresne, D. (1989) ‘Stability of pension systems when rates of return are random’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 8(1): 71–76.

Eling, M. (2012) Der Generationenvertrag in Gefahr: Eine Analyse der Transfers zwischen Jung und Alt in der Schweiz.

Eling, M. and Holder, S. (2013) ‘The value of interest rate guarantees in participating life insurance contracts: Status quo and alternative product design’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 53(3): 491–503.

Eling, M. and Kiesenbauer, D. (2013) ‘What policy features determine life insurance lapse? An analysis of the German market’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 81(2): 241–269.

FZG ’Bundesgesetz über die Freizügigkeit in der beruflichen Alters-, Hinterlassenen- und Invalidenvorsorge’, from https://www.admin.ch/opc/de/classified-compilation/19930375/index.html, accessed 1 December 2016.

Gerber, H.U. and Shiu, E.S.W. (2003) ‘Geometric Brownian motion models for assets and liabilities: From pension funding to optimal dividends’, North American Actuarial Journal, 7(3): 37–51.

Ghilarducci, T. (2010) ‘The future of retirement in aging societies’, International Review of Applied Economics, 24(3): 319–331.

Godwin, J., Goldberg, S. and Duchac, J. (1996) ‘An empirical analysis of factors associated with changes in pension-plan interest-rate assumptions’, Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 11(2): 305–322.

Jacquemart, C. (2014) Weniger Reserven, mehr Zins, NZZ am Sonntag, No 34:35.

Lisse, S. (2014) Der höchstmögliche Deckungsgrad ist nicht unbedingt der beste, finews.ch, 25 August.

Maas, P., Cachelin, J.-L. and Bühler, P. (2015) 2050: Megatrends : Alltagswelten, Zukunftsmärkte. St. Gallen: Institut für Versicherungswirtschaft.

Mirza, C. and Wagner, J. (2016) Policy characteristics and stakeholder returns in participating life insurance: Which contracts can lead to a win-win?, Risk Management and Insurance Working Paper No, 24.

O’Brien, T. (1986) ‘A stochastic-dynamic approach to pension funding’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 5(2): 141–146.

OECD (2015a) Pension market in focus, from http://www.oecd.org/finance/private-pensions/pensionmarketsinfocus.htm.

OECD (2015b) Pensions at a Glance 2015: OECD and G20 Indicators, from http://www.oecd.org/publications/oecd-pensions-at-a-glance-19991363.htm.

Poterba, J., Rauh, J.,Venti, S. and Wise, D. (2007) ‘Defined contribution plans, defined benefit plans, and the accumulation of retirement wealth’, Journal of Public Economics, 91(10): 2062–2086.

Schmeiser, H. and Wagner, J. (2014) ‘A proposal on how the regulator should set minimum interest rate guarantees in participating life insurance contracts’, The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 82(3): 659–686.

Schweizerische Kammer der Pensionskassen-Experten (2012) PKST/TSIP – Solvenztest für Schweizer Pensionskassen.

Sharpe, W.F. (1976) ‘Corporate pension funding policy’, Journal of Financial Economics, 3(3): 183–193.

Swisscanto (2015) Pensionskassen-Monitor, from http://www.swisscanto.ch/.

UBS (2014) Altersvorsorge: Lasten in die Zukunft verschoben.

Vigna, E. and Haberman, S. (2001) ‘Optimal investment strategy for defined contribution pension schemes’, Insurance: Mathematics and Economics, 28(2): 233–262.

Acknowledgements

Philipp Müller and Joël Wagner acknowledge financial support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (Grant no. 100018_159428). The authors are thankful for the comments on earlier versions of this manuscript by participants of the Western Risk and Insurance Annual Meeting 2016, the International Conference Mathematical and Statistical Methods for Actuarial Sciences and Finance 2016, the Lyon-Lausanne Seminar 2016, and the 3rd European Actuarial Journal Conference 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Müller, P., Wagner, J. The Impact of Pension Funding Mechanisms on the Stability and Payoff from Swiss DC Pension Schemes: A Sensitivity Analysis. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 42, 423–452 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-017-0048-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41288-017-0048-1