Abstract

Fiscal austerity is a policy characteristic of governments that adhere to conservative economic ideologies. In recent decades, however, especially after the 2009 Eurozone Crisis, leftist and left-centre coalition governments have also adopted austerity policies. While it is documented that fiscal austerity incurs electoral costs upon incumbent governments and these costs depend on their partisanship, whether and how the partisanship of the incumbent government affects the pattern of protest movements remains unknown. In this paper, I hypothesized that fiscal austerity by leftist governments, through adding a ‘premium’ to public grievances and demining citizens’ utility of electoral participation, results in a higher likelihood of protest movements than fiscal austerity implemented by right-dominant governments. I supported this hypothesis by analysing panel data for 37 developed countries between 1973 and 2015. Besides, the partisan-pronounced effects on the protest likelihood are observed particularly for non-violent protests such as demonstrations and strikes and for the post-2000 era.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fiscal austerity inflicts a harsh impact on citizens' economic and social well-being by worsening their employment opportunities, welfare benefits, and financial situations. Given such adverse consequences, austerity measures have fuelled furious responses from citizens in many countries, especially after the 2009 Eurozone Crisis. In Greece, for example, citizens initiated a large-scale anti-austerity movement, the ‘Indignant Citizens Movement’, through nationwide demonstrations and strikes (BBC 2010). Portuguese youth launched the campaign, Geração à Rasca (desperate generation) (Scott 2011), inspiring the neighbouring movement in Spain, the ‘15-M Movement’, to protest labour market reforms. In the United Kingdom, a group of college students called the ‘UK Uncut’ initiated direct actions against public expenditure cuts (The Guardian 2010).

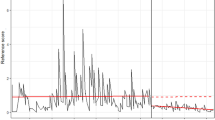

In the literature on comparative political economy, the recognition that fiscal austerity can be a significant spur to large-scale protest movements is hardly new (e.g., Paldam 1993). However, noteworthy is the fact that the frequency of such movements has surged in recent years. This is shown in Fig. 1, which tracks the annual mean number of protest movements in 37 developed countries; the trends denote a steady decline in the frequency of such movements during the 1990s and early 2000s, but a dramatic reversal after 2010.

Given the sustained interest in the role of political parties in comparative political economies, surprisingly little is known about whether and how the varying partisanship of the incumbent government affects the pattern of these anti-austerity movements. According to the classic partisan theory (e.g., Hibbs 1977), left-wing parties are more strongly committed to fiscal expansion than right-wing parties. Thus, the previous literature documents that fiscal austerity, dissonant with this traditional image, inflicts electoral losses disproportionately on left-dominant governments (e.g., Horn 2021). I argue that the logic similar to this ‘brand dilution’ thesis applies to the context of protest movements. Specifically, I contend that austerity policies, when adopted by left-dominant governments, add a ‘premium’ to public grievances, which means that public grievances are increased by the fact that the left-dominant governments initiated austerity. Core supporters of left-wing parties are likely to feel disappointed and even betrayed when their favoured government implements austerity policies. Furthermore, this may undermine confidence in the perceived utility of elections as an opportunity for expressing interests, causing these supporters to retreat from the electoral process (cf., Schäfer and Streeck 2013) and opt for other forms of political participation, possibly including protest movements (cf., Flesher Fominaya 2017). Hence, I hypothesize that austerity measures led by the left-dominant governments result in a higher likelihood of protest movements than those led by the governments of rightist parties. I tested this hypothesis by analysing panel data for 37 developed countries between 1973 and 2015 and presented supporting evidence.

Political consequences of fiscal austerity and the role of partisanship

What political consequences does fiscal austerity bring about? One of the possible consequences is ‘electoral punishment’: incumbent governments responsible for fiscal austerity incur electoral losses. This ‘electoral punishment’ thesis builds on the seminal work of Pierson (1996), which contends that welfare states inherently create supportive beneficiaries within themselves, thus deterring governments from welfare retrenchment. The empirical evidence on electoral punishment, however, is mixed: In the earlier stage of the scholarship, sometimes referring to the economic benefits of austerity (e.g., Alesina and Ardagna 2010), empirical studies emerged to cast doubt on this claim (e.g., Giger and Nelson 2011; Giger 2010; Arias and Stasavage 2019; Peltzman 1992). More recent studies, in contrast, provide empirical evidence in favour of the ‘electoral punishment’ thesis (e.g., Bojar et al. 2022; Jacques and Haffert 2021; Hübscher et al. 2021). The scholars of this line also scrutinize conditions in which the ‘electoral punishment’ thesis holds. For instance, Lindbom (2014), who analysed the effect of hospital closures, pointed out that policy transparency matters for electoral punishment. Furthermore, Hübscher et al. (2021), through a series of survey experiments, found that spending cut proposals are more likely to incur unpopularity than tax hike proposals. Bojar et al. (2022) also revealed that the adverse effects of fiscal austerity on people’s propensity to vote for incumbents depend on the unemployment rate, involvement of international organizations in such measures, and the number of concurrent protest movements.

In my opinion, however, the most important condition for electoral punishment is the type of incumbent government responsible for austerity. According to the classic partisan theory, left-wing parties, supported by lower-income groups and ordinary workers, are more strongly committed to fiscal stimuli and welfare states than right-wing parties supported by high-to-middle-income groups and businesses (e.g., Hibbs 1977). Thus, fiscal austerity led by left-dominant governments may have nuanced impacts on their electoral fortunes. One possible direction is alleviating austerity-driven electoral losses: left-wing austerity is less likely to lead to electoral defeats than right-wing austerity. The underlying mechanism, called the ‘Nixon-goes-to-China’ logic, states that left-wing parties are more advantageous than right-wing parties in blame avoidance of austerity in that they can utilize their reputation as a champion of welfare state (Ross 2000). The supportive evidence of this claim, however, is limited (see Vis 2009).

On the contrary, scholars can agree on the other direction: left-wing austerity incurs more electoral costs than right-wing austerity.Footnote 1 Schumacher et al. (2012), in line with this argument, revealed that fiscal austerity disproportionately jeopardizes the electoral performances of parties with a positive welfare image. Moreover, Horn (2021) analysed the long-term electoral performances of government parties, concluding that welfare retrenchment more adversely affects left-wing parties than right-wing parties in the long run.

The ‘brand dilution’ logic underlying this claim insightfully contends that implementing fiscal austerity is dissonant with the historical image of left-wing parties as a protector of welfare states (Horn 2021, pp. 1499–1500). In my view, the same logic applies to another political consequence of fiscal austerity: protest movements. As mentioned in the introduction, the developed world witnessed a surge of anti-austerity movements after the Great Recession and its subsequent period of austerity. In response to this political-economic landscape, a vast number of studies on anti-austerity movements have emerged thus far, highlighting a positive association between fiscal austerity and protest movements (e.g., Kriesi et al. 2020; Wågström and Taghizadeh 2021; Ponticelli and Voth 2019; Giugni and Grasso 2015, 2019; Della Porta 2015). These studies imply that fiscal austerity incurs political costs in forms, not only of electoral punishment, but also of protests. This scholarship also sheds light on the perceived dysfunction of representative democracy resulting from the situation where fiscal austerity, regardless of incumbent partisanship, was forcefully imposed by external actors such as the International Monetary Fund. As a result of eroded trust in representative democracy and people’s subsequent exit from voting participation (Schäfer and Streeck 2013; Armingeon and Guthmann 2014), fiscal austerity introduced at the initiative of international organizations is more likely to cause protest movements than measures initiated voluntarily by national governments (Altiparmakis and Lorenzini 2020).

Nevertheless, the scholarship above empirically ignores what type of incumbent government initiating fiscal austerity is particularly impactful to the occurrence of protest movements. The situation of internationally imposed austerity implies that even left-dominant governments, as the centre-left PASOK government in Greece did in 2011, carry out austerity. The ‘brand dilution’ logic mentioned above expects that left-wing austerity leads to more protest movements than right-wing austerity. Still, the scholarship has not quantitatively explored the impacts of left-wing austerity per se on protest movements.

The primary task of the present paper, therefore, was to empirically scrutinize the heterogeneous partisan effects of fiscal austerity on protest movement occurrence. In the following section, I elaborate on my own argument called the ‘leftist premium’ hypothesis. Building on the classical frameworks in social movement theory and the ‘brand dilution’ logic by Horn (2021), the hypothesis argues that fiscal austerity initiated by left-dominant governments is more likely to cause protest movements than those by right-wing governments.

‘Leftist premium’ hypothesis

In the literature on social movements, the orthodox perspective, called the ‘grievance-based perspective’ emphasizes that ‘injustices […] may motivate individuals to rebel against incumbent regimes’ (Chenoweth and Ulfelder 2016: 301). While there are many different sources of injustice, it is generally understood that personal financial difficulty is the major among them, triggering widespread grievances. As fiscal austerity is usually accompanied by personal financial hardship, especially among the worse off, their adverse consequence eventually incentivizes them to initiate or participate in protest movements.

This ‘grievance-based perspective’, however, has been criticized by a more nuanced view, recently dubbed as ‘political opportunity theory’ (e.g., McAdam 1999). This theory points out that the ‘grievance-based perspective’ considers the process of protest movements in an excessively mechanistic manner: it discounts the ‘collective action problem’ or the possibility that people may not organize or participate in protest movements even if the government’s mistreatment aggrieves them. Suggesting that grievances may not straightforwardly be translated into concrete actions by citizens, the ‘political opportunity theory’ underlines the role of the cost–benefit structures that determine the conditions under which individual citizens initiate or participate in protest movements.

How do these insights from the social movement theory help us understand protests caused by austerity? The orthodox grievance-based perspective cannot be dismissed entirely since it addresses the fundamental reasons why human beings protest or revolt. Although grievances alone may not explain everything, grievances must also exist behind the scenes of recent protests (see Chenoweth and Ulfelder 2016). As noted earlier, fiscal austerity negatively affects the well-being of citizens, primarily the less well-to-do. In this paper, I thus assumed that fiscal austerity particularly fuels the wrath of these underprivileged people, eventually driving them to take to the streets.Footnote 2

Please note here that I do not intend to deny that the more privileged feel aggrieved because fiscal austerity adversely affects macroeconomic performance by, say, reducing general consumption and investor confidence. The policy feedback and electoral punishment literature, however, implies that negative responses to fiscal austerity come mainly from the less well-to-do because they depend on public spending such as welfare benefits (Wågström and Taghizadeh 2021). More importantly, the ‘brand dilution’ claim by Horn (2021) demonstrates that right-wing voters, who probably overlap with the more privileged, support fiscal austerity if these measures achieve sound macroeconomic performances. Therefore, the assumption that the less well-to-do people are the main drivers of austerity-driven movements, I believe, is not entirely problematic.

To return to the classic social movement theory, I seriously considered the criticism from the political opportunity theory. Here, I surmised that the critical factor that constitutes the cost–benefit structures perceived by individual citizens who may or may not engage in protest movements is the partisan composition of the incumbent government responsible for fiscal austerity. Specifically, I argue that the level of public grievances that leads to actual protests is relatively higher (with the added ‘premium’) when left-dominant governments adopt the austerity policy. As reasoned in the ‘brand dilution’ thesis, implementing fiscal austerity conflicts with the conventional image of left-dominant governments as a protector of fiscal expansion, albeit consonant with the image of right-wing governments as a champion of economic liberalism (Horn 2021). Thus, leftist austerity results in much deeper disappointment than rightist austerity. For this reason, I hypothesized that a ‘leftist premium’ is added to the level of grievances, leading to a higher likelihood of protest movements when leftist governments adopt austerity policies.

Having elaborated on the role of the incumbent partisanship in the austerity-grievance linkage, how the partisanship may affect the perceived utility of elections can be discussed. In the situation of right-wing fiscal austerity, angered citizens still have the option to vote the right-wing parties out of office, following their prior (and betrayed) beliefs that the left-wing parties will retract fiscal austerity. Since the utility of electoral participation remains high in this situation, it is not so beneficial to protest to express their grievances, and the likelihood of protest movements occurring thus remains low. However, when they face austerity initiated by left-wing governments, citizens may no longer have confidence in the electoral process because there is no alternative party they can vote for in their hope of reversing austerity. Consequently, some of these citizens may choose an alternate route for voicing their interests through protest movements.Footnote 3,Footnote 4 Further, the situation where left-wing parties hold office may increase the expected benefits of initiating protest movements because the left-dominant governments may listen more sympathetically to the voices and demands expressed in such movements. Thus, austerity by left-dominant governments constitutes a more favoured political opportunity for citizens to initiate protest movements.

By extending this logic to the case where austerity is implemented by centrist governments, it is reasonable to predict that the likelihood of protest movements in such a situation is still higher than in the case of rightist austerity. Generally, citizens do not expect centrist parties to adopt austerity. For that reason, it is possible to hypothesize that a similar premium may be added to the level of public grievances against centrist governments. However, the centrist premium is unlikely to be as sizable as the leftist premium, because angered citizens still have an alternative to vote for, i.e., the leftist parties, in their hope of reversing austerity. Their sense of the efficacy of the electoral process is not entirely shattered, and at least in comparison with the case of leftist austerity, they are less motivated to take their grievances directly to the streets.

In sum, the partisanship of the incumbent government responsible for austerity affects the level of public grievances and the citizens’ belief in the effectiveness of electoral participation, which in turn, determines the likelihood of protest movements arising.

Hypothesis

The likelihood that protest movements occur in the case where fiscal austerity is implemented by leftist governments is higher than that in the case where they are implemented by rightist governments.

Corollary Hypothesis

The likelihood that protest movements occur in the case where fiscal austerity is implemented by centrist governments is higher than that in the case where they are implemented by rightist governments, but not as high as in the case where they are implemented by leftist governments.

Data and variables

In this section, I evaluate the above hypotheses based on unbalanced panel data, assembled from various sources, of 37 developed countries for the period 1973–2015.Footnote 5 I first introduce the main variables and then elaborate on the model and methods for estimation.

Dependent variables

For my key dependent variable on protest movements, I relied on Cross-National Time-Series (CNTS) data constructed by Banks and Wilson (2020).Footnote 6 Based on articles published in the New York Times, this dataset records the frequencies of anti-government demonstrations, riots, and general strikes. For the analysis below, I measured the frequency of protest movements by summing the frequencies of these three episodes.Footnote 7 The total number of protest movements thus constructed is 2069. Of the three episodes included, the most frequent are anti-government demonstrations (54.7%), riots (32.0%), and general strikes (13.3%), respectively. The Online Appendix provides the summary statistics and distribution in Table A-1 and Figure A-1, respectively. On average, protest movements are rare events in the context of modern developed countries. This increases the significance of the recent rise of protest movements, which is worth systematically investigating.

Fiscal austerity

Fiscal austerity is defined as a type of fiscal policy to consolidate budgetary soundness with spending cuts and/or tax hikes (cf. Denes et al. 2013, p. 133). To measure fiscal austerity, therefore, I used two indices capturing changes in fiscal balance as independent variables.Footnote 8 First, ΔBalance is the annual difference in government fiscal balance calculated as government revenue minus government expense as a percentage of GDP. The data on government revenues and expenses are from World Bank Open Data (World Bank 2020); a detailed description is provided in Table A-1. A higher value of ΔBalance indicates an improvement in government fiscal balance and thus captures a tendency towards austerity. Second, I used the annual difference of the cyclically adjusted primary balance, ΔCAPB. Since this indicator excludes government borrowing, interest payments, and cyclical variation in fiscal balance, it may be more suitable for measuring government fiscal policy without the influence of non-policy factors.Footnote 9 Its data source is the OECD Economic Outlook (OECD 2019). Similar to ΔBalance, a higher value of ΔCAPB captures a stronger tendency towards austerity. The description of this variable is provided in Table A-1. For the distributions of these two variables, see Figure A-2.

In prior research on related subjects, two different approaches were used to measure fiscal austerity. The so-called narrative approach, adopted by earlier studies such as Paldam (1993), as well as more recent and sophisticated works by Muñoz et al. (2014), determines the duration of austerity measures by citing historical documents. The other utilizes standard economic indicators such as fiscal balances described above. While the narrative approach can exclude ‘non-policy changes correlated with other developments affecting output’ (Guajardo et al. 2014, p. 950), the critical disadvantage is its dependence on the observer’s arbitrary decisions on what events and incidents can be regarded as changes in the government’s fiscal policy. I opted for the latter approach, as it is accepted in the literature (e.g., Ponticelli and Voth 2019; Voth 2011).

Partisanship

To measure government partisanship, I adopted the procedure as follows: First, I collected data on left–right orientations of political parties from the ParlGov database, which covers established democracies, namely, all EU and most OECD member countries (Döring and Manow 2019). In this dataset, each party’s position is rated, based on expert surveys, on a 1-to-10 continuous scale. If this variable is close to 1, the party orientation is judged to be left. If the variable is close to 10, the orientation is judged to be right.

Second, based on this data, I adopted two approaches to define government partisanship. The first approach is to use the partisan variable only for those parties to which the prime ministers belong in a country-year, assuming that they are the ultimate decision-makers responsible for austerity measures. An objection could be that this treatment disregards other informational details of each government, such as its majority-minority status or the precise composition of other parties in a coalition. This objection brings us to the second approach, which considers all governing parties. This approach defines government partisanship as a weighted average of all governing parties. For more details on the calculation, see Online Appendix B.

Third, further adjustments were in order concerning the timing of government change and policy initiation since the ParlGov database does not take the form of country-year panel data. Note that in most countries, the government fiscal schedule is such that its budget plan is decided before an actual fiscal year starts. This might create a measurement error; for example, if a positive change in budget balance is recorded in a country-year and the government partisanship in that country-year is coded based on its orientation as of April. If the actual inauguration of this government occurred after April, the fiscal improvement should be attributed to the policy of the previous government, not the current one. To manage this potential problem, I defined partisanship each year based on the ideological position of the prime minister’s party or all governing parties that hold office as of 1st January in the year.

Finally, I converted these prime minister and government partisan variables into the 3-point-scale variables of partisanship of prime minister parties and all governing parties, for ease of interpreting the results, especially for the interaction terms. This was coded 0 if the government is recognized as right-wing, 1 if centrist, or 2 if left-wing. The cutting points were set so that the sample was evenly broken down into three subsets. For a robustness check, I also used the continuous version mentioned above. Note that these continuous variables were negated in the analyses to make them aligned with the categorical variables because an increase in the original continuous variables captures more right-wing tendencies.

In sum, I had four different partisanship variables: ‘Partisanship (Categorical-PM)’ is the three-point-scale variable for prime minister (PM) parties; ‘Partisanship (Continuous-PM)’ the (negated) continuous variable for PM parties; ‘Partisanship (Categorical-Govt)’ the three-point-scale variable for all governing parties; ‘Partisanship (Continuous-Govt)’ the (negated) continuous variable for all governing parties. Descriptive statistics for these parties are shown in Table A-1. The means of the two categorical variables are close to 1, indicating that the conversion works appropriately. For limited space, the analyses below use only ‘Partisanship (Categorical-PM)’. Online Appendix C shows the results for the other variables.

Control variables

I considered and listed some covariates that may affect the frequency of protest movements (see Table A-1 for the summary statistics and sources for these covariates). First, I controlled for the population scale, given that (more) frequent occurrence of protest movements may reflect a large(r) national population. Specifically, I included the population logarithm; these data were retrieved from Banks and Wilson (2020). Second, I controlled for general economic situations because the worsening of economic conditions may encourage protest movements (e.g., Acemoglu and Robinson 2001). Specifically, I considered macroeconomic indicators, including economic growth, unemployment, and inflation. Finally, considering the possibility that democratic institutions and mature civic culture may constitute necessary conditions for any social movements, I included the Polity 2 variable that measures a given regime’s degree of democracy (Marshall and Gurr 2020). Including this control variable responds to the modernization theory in social movement studies, respectively (see Chenoweth and Ulfelder 2016).

Model and methods for estimation

As hypothesized above, I intended to examine whether fiscal austerity adopted by left-dominant governments has stronger (positive) effects in stimulating protest movements than that adopted by rightist governments. For this, I estimated the following model:

where \({\alpha }_{1i}\), \({\alpha }_{2t},\) and \({\alpha }_{3it}\) denote country-, period-, and individual-level constants, respectively, and \({{\varvec{\beta}}}^{{\varvec{T}}}{\varvec{X}}\) represents control variables and their coefficients.

According to the literature, austerity increases the likelihood of protest movements, therefore \({\beta }_{1}\) should be greater than zero. As for \({\beta }_{2}\), my hypothesis remained agnostic as I supposed that the likelihood of citizens initiating protest movements does not depend directly on whether the incumbent government is leftist or rightist. Far more important to my hypothesis is \({\beta }_{3}\), namely, the estimated coefficient for the interaction between government fiscal policy and incumbent partisanship. Since a greater value denotes the government’s leftist orientation, \({\beta }_{3}\) is expected to be positive if my hypothesis is true.

Given that the dependent variable is a count variable that takes non-negative values and is positively skewed, as shown in Figure A-2, ordinary least square estimation was not appropriate. Thus, I used negative binomial regression models which are used widely in count data analysis in political science. As another option, Poisson regression assumes that the mean of the dependent variables equals the variance. It is often suggested that this method may be unsuitable for analysing over-dispersed data. The standard deviation of the dependent variable is 4.1, which is greater than the mean of 1.5. Thus, I used the negative binomial as the main estimation model and employed Poisson estimation for a robustness check (see Online Appendix I).

Empirical findings

Main findings

Table 1 provides the results based on the negative binomial regression analyses with the 3-point-scale categorical partisan variable of PM parties (Partisanship [Categorical-PM]). The first three models (Models 1–3) include an annual difference in government fiscal balance (ΔBalance) as a measure of government fiscal policy. As shown, ΔBalance is estimated to have a negative impact on the dependent variable. Contrary to previous scholarship, this result suggests that governments’ effort to improve their fiscal balance inhibits citizens from initiating protest movements. However, the estimated effects are not significant at conventional levels, thus rendering it difficult to draw any conclusive inference on this point. Turning to the partisan variables, they have consistently negative and significant effects, denoting that left-dominant governments per se have the effects of inhibiting the occurrence of protest movements.

The most important and novel finding of my empirical analysis concerns the interaction (ΔBalance*Partisanship [Categorical-PM]). The interaction is estimated to consistently have positive effects on the dependent variable, and the effect is significant in Models 2 and 3, which include a set of control variables. This result demonstrates that austerity measures implemented by the leftist PM’s governments increase the likelihood of protest movements more than austerity measures initiated by centrist and rightist governments. Models 4–6 include an annual difference in ΔCAPB to measure government fiscal policy. In contrast to ΔBalance, ΔCAPB has consistently positive effects on the dependent variable, indicating that governments’ efforts to improve their fiscal balance may encourage citizens to initiate protest movements. This result is consistent with previous scholarship. The interaction between ΔCAPB and partisanship is estimated to have positive effects on the dependent variable, but they are insignificant.

For visualization, Fig. 2 depicts the marginal effects of the fiscal policy variables on the dependent variables. Note that the impact clearly differs according to the PM’s partisanship (right, centre, or left). According to Panel A, the marginal effect of ΔBalance on the dependent variable is close to zero when PMs come from right-wing parties. In contrast, the marginal effects of the increase in government revenue conducted by the centrist and leftist PM’s governments exceed zero, and their 95% confidence intervals do not intersect the zero-horizontal line. This result supports my main hypothesis. Panel B also demonstrates a similar result, while rightist austerity has no effect on the likelihood of protest movements, centrist and leftist austerity has significantly positive effects. Although Table 1 does not show significant effects of the interaction for ΔCAPB, this figure indicates that fiscal austerity by leftist and centrist PMs significantly increases the likelihood of protest movements. However, neither Panels A nor B provide explicit support for my corollary hypothesis. Although the marginal effects for the leftist PM’s governments appear slightly larger than those for centrist PMs, their confidence intervals overlap each other. This implies, contrary to the initial prediction, that austerity initiated by centrist PMs gives a premium to public grievances and that its amount is as sizable as the leftist premium.

Marginal effects of fiscal policy by PM partisanship. Note Each panel was drawn based on Models 3 and 6 in Table 1, respectively

To discuss the substantial meaning of the results above, Fig. 3 illustrates how the predicted number of protest movements changes depending on the magnitude of fiscal austerity and the partisanship of the PMs responsible for it, demonstrating that large-scale austerity–which is common, specifically in the post-Crisis period–by centrist and left-wing PMs leads to more protest movements than that by right-wing PMs. Suppose the magnitude of austerity is relatively small (less than a ca. 3-point improvement in fiscal balance as a percentage of GDP). In that case, the predicted average of protest movements is more for right-wing PMs (ca. 0.5) than for centrist (ca. 0.25) and left-wing PMs (ca. 0.1), reflecting that the effect of the PM partisanship itself is significantly negative. However, if its magnitude becomes larger (i.e., more than a ca. 3 improvement), more protests are predicted for centrist and left-wing PMs than for right-wing PMs on average. More importantly, the predicted average for right-wing remains below 0.5 per year regardless of the magnitude of austerity, whereas that for centrist and left-wing increases to 0.7 and 1 per year at maximum, respectively. In summary, this result implies that my argument holds, specifically in the context of large-scale austerity.

Here I briefly summarize the results using other measurements of incumbent partisanship (see Online Appendix C). The analysis using the continuous measurement of PM parties (Partisanship [Continuous-PM]) shows significant effects of the interaction terms of interest, not only for ΔBalance but also for ΔCAPB (see Table C-2). The effects of the interaction are suppressed in most models when I use the categorical measurement of all governing parties (Partisanship [Categorical-Govt]) (see Table C-3), but they become clear again for ΔBalance when I use the continuous version of this measurement (Partisanship [Continuous-Govt]) (see Table C-4). In summary, the result presented above is not robust to the measurements of partisanship, but I discuss this point in the next subsection.

Dependent variable decomposition

Since the dependent variable used in the above results was constructed by aggregation, I decomposed it into three episodes of protest movements, namely, demonstrations, riots, and general strikes, and estimated separately based on the negative binomial regression method. The results are shown in Table 2. Models 1–3 include ΔBalance as the measurement of government fiscal policy, whereas Models 4–6 include ΔCAPB. Across these six models, the interactions between fiscal policy and partisanship (Partisanship [Categorical-PM]) have significant effects only for the models whose dependent variable is demonstrations. Online Appendix D also reveals the significant interaction effects between ΔBalance and three of the four partisanship variables on strikes. The hypothesis is not supported for violent movements. The most notable is that the interactions of ΔCAPB and partisanship, which were insignificant in the main results, have significant impacts on demonstrations for all the partisanship variables regardless of the partisan variables, implying that my core argument holds particularly for this type of protest. This asymmetry of the disaggregated analysis is hardly surprising. The apparent absence of the effect of left-wing austerity on violent movements is compatible with the discussion of Flesher Fominaya (2017), who characterizes the anti-austerity movement as ‘pro-democracy’.

Period comparison

Given that my hypotheses implicitly built on the recent situation where the number of protest movements skyrocketed, as Fig. 1 demonstrates, it was relevant to ask whether my finding applies only to the current era. Thus, I replicated the main analysis in Table 1 with the target period divided into two: 1972–1999 and 2000–2015. Table 3 shows the result of this analysis. Models 1–3, which cover the period between 1972 and 1999, show no significant effects of the interactions of interest, whereas Models 4–6 for 2000–2015 consistently do, implying that my core argument holds only for the more recent contexts. Online Appendix D provides the results of analyses using the different measurements of partisanship, producing a similar interpretation.

Other robustness checks

I conducted some additional robustness checks, and their results are shown in the Online Appendix. First, in Appendix F, I estimated the models with dummy specifications of the partisan variables to relax the linearity assumption of the ordinal specifications above.Footnote 10 Table F-1 shows the results of the PM parties’ partisanship, indicating that improvement in ΔBalance, not ΔCAPB, under a left-wing PM results in more protests than a right-wing PM. The difference in the effect of ΔBalance between centrist and right-wing PMs is insignificant. Table F-2, on the other hand, shows the significant difference in the effect of ΔCAPB, not ΔBalance, between left-wing and right-wing PMs. Likewise, there is no significant difference between the centrist and rightist. Second, I ran negative binomial regressions, excluding country dummies, as the simultaneous estimation of lagged dependent variables and country-fixed effects may cause the endogeneity problem (Angrist and Pischke 2009). Appendix G shows the result of this analysis, producing a similar finding to the main analyses. Third, I conducted additional analyses to check how each control variable affected the inferences of my main analyses, as Appendix H shows. According to Table H-1, which provides the results of the one-by-one covariate inclusion for ΔBalance, including either log population, ΔGrowth, or ΔUnemployment provides the result favourable to my core argument. The same procedure applied to ΔCAPB did not change the finding that the interaction between ΔBalance and partisanship is insignificant. Finally, as I said in the previous section, I ran Poisson regressions with the same variables included. The results in Appendix I provide more apparent and supportive evidence for my core argument than the main results. In sum, these results do not undermine my main findings presented above.

Conclusion

In summary, the empirical analyses revealed some important insights. First and most importantly, the effect of fiscal austerity depends on the partisanship of the government responsible for such measures: austerity conducted by left-dominant governments has stronger effects on the likelihood of protest movements than austerity measures undertaken by their right-wing and centrist counterparts. Second, such partisan-pronounced effects are observed particularly for anti-government demonstrations and strikes, not for riots, implying the ‘pro-democratic’ characteristic of austerity-driven protests. Third, and finally, the period comparison reveals that these effects hold for the more recent era, namely post-2000. In general, these findings buttress my core argument.

The main contribution of this paper is that it expands the scope of the partisanship theory. It presented the possibility and necessity that consequences, other than policies or performances, should be taken seriously in the context of this theory. Although some scholars contend that the role of partisanship in the decision-making process of economic policies is diminishing (e.g., Cusack 1999), the findings of this study imply that partisanship makes a difference if we focus on the consequences following fiscal policy: protest movement.

I am aware that the present paper has limitations. Among them is that it was not able to identify whether my findings of partisan-conditioned effects result from the very fact of left-wing austerity. Left- and right-wing governments may differ in terms of austerity measures: the latter, for example, may focus more on spending cuts on education and environment policies than the former (Herwartz and Theilen 2020). These differentiated patterns may have underlain the partisan-conditioned effects that my analyses revealed. To address this problem, future research would benefit from, say, scrutinizing which categories of spending cuts are more impactful on protest occurrence.

Notes

The study of Giger and Nelson (2011) is compatible with this direction. Their core finding is that fiscal austerity does increase votes for liberal parties since these measures are conceived of as a representation of ‘market liberalism’.

Implicit in my argument here is that the objective of protest movements is simply to ask the government to withdraw fiscal austerity, not to overthrow their regimes. Regarding the protest movements in democratic countries under consideration in this paper, I believe this is not a problematic assumption; anti-government movements in authoritarian regimes may, of course, have different objectives.

This mechanism can be paraphrased by the exit-voice framework of Hirschman (1970). The decreased utility of electoral participation means the disappearance of an exit option that constitutes a solution to a collective action problem in expressing voices, namely, initiating protest movements.

I am aware that this anticipation relies on an untested assumption: citizens who are disappointed by the effectiveness of electoral participation will automatically and immediately move to another form of political participation—protest movements. However, disappointed citizens may retreat from political participation entirely instead of protesting. Future research would benefit from employing micro- and multi-level empirical strategies to test this assumption.

The data covers Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, and the United Kingdom.

I am aware that CNTS data has been criticized for its problems of ‘the potential for reporting bias and the lack of coverage of smaller events’ (Ulfelder 2005, p. 321), as it relies on a specific newspaper in a specific country and sets a threshold of the number of participants in coding protest events. The CNTS data, however, has been used widely in the current research related to social movements, because this dataset has an distinct advantage in terms of its extensive coverage, compared with other available datasets which only cover the developing world (e.g., Salehyan et al. 2012). This is particularly true with the analysis of the present paper, which focuses on the political economy of developed countries.

The same formula is used by Ulfelder (2005).

According to some arguments, visible austerity measures, such as welfare cuts, are more likely to stimulate public responses (Lindbom 2014; Hübscher et al. 2021); therefore, I am aware that my strategy to use change in fiscal balance, which is much less invisible than welfare cuts, is not free of criticism. Conversely, however, my strategy is methodologically conservative in that it uses less advantageous measurements to test my arguments. It is plausible that if my argument holds for less visible measurements, it also holds for more visible measurements.

The CAPB is widely used by economists (e.g., Alesina and Ardagna 2010).

The reference category is set to right-wing prime minister or government.

References

Acemoglu, D., and J. Robinson. 2001. Theory of Political Transitions. American Economic Review 91 (4): 938–963. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.4.938.

Alesina, A., and S. Ardagna. 2010. Large Changes in Fiscal Policy: Taxes Versus Spending. Tax Policy and the Economy 24 (1): 35–68. https://doi.org/10.1086/649828.

Altiparmakis, A., and J. Lorenzini. 2020. Bailouts, Austerity, and Protest: Representative Democracy and Policy-Making in Times of Austerity. In Contention in Times of Crisis : Recession and Political Protest in Thirty European Countries, ed. H. Kriesi, J. Lorenzini, B. WüestandS, and Hausermann, 184–205. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Angrist, J.D., and J.-S. Pischke. 2009. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Arias, E., and D. Stasavage. 2019. How Large Are the Political Costs of Fiscal Austerity? The Journal of Politics 81 (4): 1517–1522. https://doi.org/10.1086/704781.

Armingeon, K., and K. Guthmann. 2014. Democracy in Crisis? The Declining Support for National Democracy in European Countries, 2007–2011. European Journal of Political Research 53 (3): 423–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12046.

Banks, A.S., and K.A. Wilson. 2020. Cross-National Time-Series Data Archive. Jerusalem: Databanks International.

BBC. 2010. Three Dead as Greece Protest Turns Violent. 5 May. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/8661385.stm. Accessed 12 Sept 2020.

Bojar, A., B. Bremer, H. Kriesi, and C. Wang. 2022. The Effect of Austerity Packages on Government Popularity During the Great Recession. British Journal of Political Science 52 (1): 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123420000472.

Chenoweth, E., and J. Ulfelder. 2016. Can Structural Conditions Explain the Onset of Nonviolent Uprisings? Journal of Conflict Resolution 61 (2): 298–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002715576574.

Cusack, T. R. 1999. Partisan Politics and Fiscal Policy. Comparative Political Studies 32 (4): 464–486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414099032004003.

Della Porta, D. 2015. Social Movements in Times of Austerity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Denes, M., G.B. Eggertsson, and S. Gilbukh. 2013. Deficits, Public Debt Dynamics and Tax and Spending Multipliers. The Economic Journal 123 (566): F133–F163. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12014.

Döring, H., and P. Manow. 2019. Parliaments and Governments Database (Parlgov): Information on Parties, Elections and Cabinets in Modern Democracies. Development Version. http://www.parlgov.org/. Accessed 29 Jan 2020.

Flesher Fominaya, C. 2017. European Anti-Austerity and Pro-Democracy Protests in the Wake of the Global Financial Crisis. Social Movement Studies 16 (1): 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2016.1256193.

Giger, N. 2010. Do Voters Punish the Government for Welfare State Retrenchment? A Comparative Study of Electoral Costs Associated with Social Policy. Comparative European Politics 8 (4): 415–443. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2009.4.

Giger, N., and M. Nelson. 2011. The Electoral Consequences of Welfare State Retrenchment: Blame Avoidance or Credit Claiming in the Era of Permanent Austerity? European Journal of Political Research 50 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2010.01922.x.

Giugni, M., and M.T. Grasso, eds. 2015. Austerity and Protest: Popular Contention in Times of Economic Crisis. London: Routledge.

Giugni, M., and M.T. Grasso. 2019. Street Citizens: Protest Politics and Social Movement Activism in the Age of Globalizatio. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Guajardo, J., D. Leigh, and A. Pescatori. 2014. Expansionary Austerity? International Evidence. Journal of the European Economic Association 12 (4): 949–968. https://doi.org/10.1111/jeea.12083.

Herwartz, H., and B. Theilen. 2020. Government Ideology and Fiscal Consolidation: Where and When Do Government Parties Adjust Public Spending? Public Choice 187 (3–4): 375–401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-020-00785-7.

Hibbs, D.A. 1977. Political Parties and Macroeconomic Policy. American Political Science Review 71 (4): 1467–1487. https://doi.org/10.2307/1961490.

Hirschman, A.O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Horn, A. 2021. The Asymmetric Long-Term Electoral Consequences of Unpopular Reforms: Why Retrenchment Really Is a Losing Game for Left Parties. Journal of European Public Policy 28 (9): 1494–1517. https://doi.org/10.1080/13501763.2020.1773904.

Hübscher, E., T. Sattler, and M. Wagner. 2021. Voter Responses to Fiscal Austerity. British Journal of Political Science 51 (4): 1751–1760. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007123420000320.

Jacques, O., and L. Haffert. 2021. Are Governments Paying a Price for Austerity? Fiscal Consolidations Reduce Government Approval. European Political Science Review 13 (2): 189–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1755773921000035.

Kriesi, H., J. Lorenzini, B. Wüest, and S. Hausermann, eds. 2020. Contention in Times of Crisis : Recession and Political Protest in Thirty European Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lindbom, A. 2014. Waking up the Giant? Hospital Closures and Electoral Punishment in Sweden. In How Welfare States Shape the Democratic Public: Policy Feedback, Participation, Voting, and Attitudes, ed. S. Kumlinand and I. Stadelmann-Steffen. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Marshall, M.G., and T.R. Gurr. 2020. Polity 5: Political Regime Characteristics and Transitions, 1800–2018. Center for Systemic Peace.

McAdam, D. 1999. Political Process and the Development of Bliack Insurgency, 1930–1970. Chicago: The Univercity of Chicago Press.

Muñoz, J., E. Anduiza, and R. Guillem. 2014. Empowering Cuts? Austerity Policies and Political Involvement in Spain. In How Welfare States Shape the Democratic Public: Policy Feedback, Participation, Voting, and Attitudes, ed. S. Kumlinand and I. Stadelmann-Steffen. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

OECD. 2019. OECD Economic Outlook, Volume 2019 Issue 2. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/9b89401ben.

Paldam, M. 1993. The Socio-Political Reactions to Balance-of-Payments Adjustments in Ldcs: A Study of Nine Cases from Latin America. Aarhus University.

Peltzman, S. 1992. Voters as Fiscal Conservatives. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 107 (2): 327–361. https://doi.org/10.2307/2118475.

Pierson, P. 1996. The New Politics of the Welfare State. World Politics 48 (2): 143–179. https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.1996.0004.

Ponticelli, J., and H.-J. Voth. 2019. Austerity and Anarchy: Budget Cuts and Social Unrest in Europe, 1919–2008. Journal of Comparative Economics 48 (1): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jce.2019.09.007.

Ross, F. 2000. ‘Beyond Left and Right’: The New Partisan Politics of Welfare. Governance 13 (2): 155–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00127.

Salehyan, I., C.S. Hendrix, J. Hamner, C. Case CLinebarger, E. Stull, and J. Williams. 2012. Social Conflict in Africa: A New Database. International Interactions 38 (4): 503–511.

Schäfer, A., and W. Streeck. 2013. Introduction: Politics in the Age of Austerity. In Politics in the Age of Austerity, ed. A. Schäferand and W. Streeck, 1–25. Cambridge: Polity.

Schumacher, G., B. Vis, and K. van Kersbergen. 2012. Political Parties’ Welfare Image, Electoral Punishment and Welfare State Retrenchment. Comparative European Politics 11 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1057/cep.2012.5.

Scott, B. 2011. Geração À Rasca - Nytimes.Com. The New York Times. https://schott.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/05/05/geracao-a-rasca/. Accessed 12 Sept 2020.

The Guardian. 2010. High Street Stores Hit in Day of Action over Corporate Tax Avoidance. 19 December. https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2010/dec/19/uk-uncut-tax-avoidance-protests. Accessed 12 Sept 2020.

Ulfelder, J. 2005. Contentious Collective Action and the Breakdown of Authoritarian Regimes. International Political Science Review 26 (3): 311–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512105053786.

Vis, B. 2009. Governments and Unpopular Social Policy Reform: Biting the Bullet or Steering Clear? European Journal of Political Research 48 (1): 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6765.2008.00783.x.

Voth, H.-J. 2011. Tightening Tensions: Fiscal Policy and Civil Unrest in Eleven South American Countries. In Fiscal Policy and Macroeconomic Performance, ed. L.F. Céspedes and J. Galí, 1937–1995. Santiago de Chile: Central Bank of Chile.

Wågström, M.B., and J.L. Taghizadeh. 2021. The Welfare State Upholders: Protests against Cuts in Sickness Benefits in Sweden 2006–2019. Scandinavian Political Studies 44 (3): 321–345. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9477.12201.

World Bank. 2020. World Bank Open Data. World Bank. https://data.worldbank.org/ Accessed 20 July 2020.

Funding

Funding was provided by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grant No. 19J14502).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Suzuki, J. A ‘leftist premium’ to protest movements?: How incumbent partisanship conditions austerity-spurred mass protest. Acta Polit 59, 124–144 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00283-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-022-00283-2