Abstract

Reputation is an intangible asset that directly affects the market value of the firm. Although reputation evidences belief that the firm is on a sustainable course, it is built on the trust established with all stakeholders through past proper behaviour. It proves more resilient than one might think at first but even menial misconducts, if repeated, can lead to a downfall. The demise of a few can engulf a whole industry when the transactions are based on trust in the fulfilment of future promises. This is why reputation has become an object of research for several branches of management sciences. The key drivers are still in need of refinement. Nevertheless, they can be summarized in one word: authenticity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Reputation is a social construct that rests on individuals' beliefs and perceptions. It has grown into a significant economic factor, often now considered within organizations as an intangible asset. When considering how to assign a value to reputation, the most sensible approach is probably to compute it as the difference between the market value of the stock and the total of tangible assets and those intangible assets readily assessable, like lease, licences, etc. Although reputation is an intangible asset to which no value is assigned by accounting conventions, it is, undoubtedly, one of the most valuable assets of any company, and particularly of a global financial institution.

Indeed, most organizations have come to consider reputation as their most vulnerable asset;Footnote 1 however, this might stem from an overestimate of the real costs and possibly the benefits associated with it. Most scholars and practitioners seem to agree with Warren Buffet, CEO, Berkshire Hathaway, that “It takes twenty years to build a reputation and five minutes to destroy it.” This may not always be the case as some reputations have resisted major events in the past, like the Swissair commercial rebound after their loss of a flight over the North Atlantic. It is true that some organizations like Enron or Arthur Andersen have suffered from damage to their reputation leading to their ultimate bankruptcy. The case is even clearer for the audit firm whose clientele depends on the trust of the financial community. On the other hand, unexpectedly, several organizations, Bank of America, Wachovia and City Group, to name but a few, have benefited from attacks on their reputation, their share prices having even experienced sharp rises in the process.Footnote 2 In fact, as the examples mentioned above indicate, some studies show that it is possible to navigate out of a crisis in which the reputation is at stake with an enhanced image. This may seem like a paradox. However, for example, for a company with limited resources to allocate to advertising, a crisis may represent an opportunity to “exist” in different media, even on television, at no cost. Of course benefiting from a crisis is also a tremendous challenge; it involves enhancing the public trust in the company. The key factor is the directors' and officers' behaviour throughout the crisis. They must show leadership, and specifically prove able to avoid an “ethical misconduct disaster.”Footnote 3 With this important proviso, reputation might prove a much more resilient asset than many believe.

Therefore, as in many “risky situations,” attacks on reputation can prove to be threats as well as opportunities, probably depending in part on how the executives' behaviour in the “crisis” is perceived by major stakeholders. As scholars of risk, we must investigate these diverse instances and try to decipher more precisely what are the root causes that lead to disaster in some cases and asset improvement in others. This investigation can only be thorough if conducted in a trans-disciplinary fashion, that is, through a global approach. Is it conceivable that the attacks on reputation would be better understood if split in different classes? Hence, their very different impacts could be explained.

To narrow the scope of this paper, we pose an assumption, namely that the organization has already developed a strong reputation, thus excluding those organizations in the process of building their reputation.

The hypothesis in this paper is that the organization becomes vulnerable when attacked on its “core business.” If the attack target is outside of its core business, the organization may rebound higher and thus the risks on its reputation may create tremendous opportunities.

From this hypothesis and assumption, we derive two postulates. First, reputation creates a competitive advantage for the organization considered; therefore, it has a keen interest in the furthering and consolidation of its reputation. The second postulate is that the subjective value allocated by a firm, an individual or any other type of organization to reputation is strongly correlated with the concept of corporate governance and social responsibility.

Therefore, our first approach will be to scan through the treatment of the concept of reputation by different disciplines of management science. Then, we will address the question of sustaining and enhancing a reputation, more specifically in the insurance and reinsurance industries, using recent studies by two prestigious consulting firms and our own investigation with a restricted panel of industry experts. Finally, we will explain the close links between corporate governance and reputation through the threats and opportunities stemming from both, in the light of stakeholder perceptions and expectations.

An Overview of Risks to Reputation in Management Science

Although reputation emerged as a key concept in several branches of management science in the late 1990s, it still does not necessarily cover the same fundamental aspects now. Some will concentrate on the drivers to develop a reputation management tool kit whereas others will look mostly at reputation as a vehicle for information in the process of partnership building.

In economic science, reputation and its associated risks have emerged as early as the 60s.Footnote 4 However, it was only during the 90s that the concept became an object of studies.Footnote 5 The coordination of activities within an organization is analysed as a non-cooperative game based on reciprocal trust on the part of the players who take the risk that the “other” may benefit unilaterally from the contract. If the game is played only once, then the only equilibrium that can be reached is an inefficient solution based on mistrust. On the other hand, should the game be repeated indefinitely, an implicit trust contract is established between the players. The difficulty stems from the inability to measure directly this trust-building through the multiple transactions, whereas the trust level achieved is the basis for “fair trading.” Therefore, there must be some commonly accepted way to enforce that “trust contract,” that is, a socially measurable proof of trustworthiness of the partners; this is precisely what reputation is about when it allows for a trust contract to be entered into by parties with no prior experience of transactions – hence, the notion of focal principlesFootnote 6 built throughout the history of an organization and serving as attributes to reputation. Thus, reputation is considered as a vehicle of information and constitutes the foundation to ensure efficient cooperation between organizations.

On these founding assumptions, a body of research has been developed on collective reputation to an extent that is beyond the scope of this article. By collective reputation of an organization the authors refer to the past typical behaviour of the organization's members. However, as elaborate and sophisticated as the different models proposed by the economists may be, they all rest on the following four hypotheses:

-

The reputation of a group results from the individual reputation of its members;

-

Past individual behaviours are assumed to be imperfectly observable (this imperfect information is the reason why there is need for the concept of reputation);

-

The past history of any member of a group is used to predict his future behaviour (consistency through time: hence past individual behaviour influences the collective reputation – see first bullet above);

-

The behaviour of a new member of the group is influenced by his/her predecessors' past behaviour.

Without going into details in that area, we must stress that the collective reputation concept could be extended to an industry sector, for example the insurers, the bankers, and other sectors have a collective reputation that they may want to protect and enhance while at the same time they want to stress their individual differences in life outside of the group. Furthermore, whom the organization is associated with through upstream as well as downstream partnership has a bearing on its “collective reputation.” In any case, the reputation is the result of the perceptions of many different stakeholders and there are always conflicting expectations, such as those between stockholders and customers; these must be addressed and resolved in an orderly fashion in order to avoid unnecessary risks.

However, this purely economic approach is not very realistic. The main limitations of the construction of this type of trust game, based on reputation are that:

-

It rests on the hypothesis that the game is repeated indefinitely. What would be the interest in maintaining a good reputation when the last period is reached and no more will follow?

-

It rests also on the premise that each player knows how the other behaved in the past. However, it may happen that one player is unhappy about the other's reputation because he is bad tempered. Therefore, the other player's opinion is necessary but not sufficient to determine each player's reputation.

-

It does not take into account the possibility of forgiving and forgetting if one player implores his partner and undertakes to remedy the injuries suffered in the interest of the community of players.

-

It does not reflect the relationships found on the employment market where hierarchies and conflicting interests blur the picture.

-

It does not capture the changes in the environment, in particular, those stemming from training and learning from past mistakes.

When the limitations listed above are accounted for, it becomes practically impossible to use such a model to explain the environment. It is therefore necessary to bring into the picture the problems linked with bilateral cooperation where, for example, one company competes with another as long as this second firm is expected to do so. Equilibrium can be reached through what is known as the “folk theorem”.Footnote 7 A reasonable level of cooperation can be maintained because the player would not proceed under the threat of some form of penalty. This type of game approach has lead to many applications based on threats and promises (opportunities) that are only credible insofar as reputation upholds them.

In the finance theory, reputation is also tackled through the angle of beliefs, justified or not, that will lead a financial institution to grant a loan to a given entrepreneur. For most experts, the basic model used is modified to include an additional parameter (to reflect reputation) and then the utilities thus derived are compared between models while retaining the “expected utility”Footnote 8 maximization criterion.Footnote 9

In order to have a better assessment of this financial reputation, the Observatoire de la Réputation was founded in France by M. Fombrun and it released its first rating, “Rvad,”Footnote 10 on the financial reputation of listed companies based on a scale from R to RRRRR as early as 1994. Six stocks were rated RRRRR and RRRR (Air liquide, Danone, L'Oréal, Canal+, Carrefour, Total) and 10 RRR or more (the six already mentioned and Sanofi-Aventis (then Rhône-Poulenc), LVMH, Société Générale). These are interesting results that corroborate those published by Fortune, to which we will refer to later.

In the field of insurance, as in marketing, the research is based on the trust game of Kreps.Footnote 11 The act of purchasing is grounded on trust, of which reputation is one of the drivers. One must measure the performance of the reputation evaluation key and assess its impact on pricing in a situation where the information distribution is asymmetrical.Footnote 12 The Kreps sequential game is a useful illustration of the difficulties encountered in these two disciplines. In the case where the transaction effectively takes place, the seller faces two possibilities. Either he respects the buyer's trust and delivers high quality goods or services, resulting in a gain for both the seller and the buyer; or he takes advantage of the buyer's trust in offering him poor quality goods or services, with the buyer experiencing a loss and the seller achieving (temporarily) a higher gain than in the preceding situation.

In the insurance industry, this “moral hazard” situation can be also a source of adverse selection.Footnote 13 It is characterized by some insurers' behaviour that, because they are covered through insurance contracts, prove to be negligent, and even risk seekers in the matter or action for which they are covered. In such a case, there is no mutually beneficial exchange. The results arrived at by these authors on competitive mechanisms are still robust today.Footnote 14

Several marketing articles focus on on-line reputation systems, and the risks stemming from the use of new technologies. Transactions are not so numerous as on traditional markets. The eBay case has been used in many studies;Footnote 15 the site invites self-evaluation for each transaction between a seller and a buyer. Therefore, the risk stemming from reputation has a considerable impact on the level of trust in any transaction. When the evaluation is positive, the individual is credited one point. If it is neutral, there is no change in points, and if it is negative, he is debited one point. This scoring scale provides an evaluation profile for each member but falls short of defining a criterion for reputation because it is heavily dependent on the number of transactions in which the individual entered. Although they generally agree on the existence of a “substantial” reputation premium, so far the authors have proved unable to quantify it; however, they demonstrate that reputation reduces the information asymmetry and therefore allows the markets to operate more smoothly and in the end to manage more efficiently the risks induced.

Other papers try to evaluate how much consumers really care about corporate reputation when it comes to purchasing decisions.Footnote 16 The “corporate reputation” is then an extension of the brand image (more static), sometimes referred to as “corporate brand,” often identified by a simple name, sometimes a logo. This statement may be an oversimplification and requires some further explanation: some firms have a single monolithic “corporate brand” (e.g. Air France, Danone), others pursue a deliberate strategy of cultivating individual product brands (e.g. Diageo, KJSFootnote 17) and the corporate name is deliberately subordinated. In the latter case, consumers may be unaware of Diageo's or KJS's corporate reputation as they only recognize product brands. In the case of Air France or Danone, significant damage to corporate reputation could prove catastrophic. Furthermore, Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) offering intermediate goods and services may not even have a “brand image” to speak of, and yet they thrive thanks to the reputation they enjoy with their economic partners. It suffices to stress that insurance and reinsurance companies are typically “one brand” firms with the life and P&C companies sharing the same name and the logo flourishing on all the agents' networks. However, in most situations, reputation contributes to the intrinsic value of the brand (or brands) and represents one element of the firm's identity. The legal protection of the brand is one means of preserving competitive advantage, but it is not sufficient by itself to strengthen the relationship with the partners (customers, suppliers, project associates, employees). A “good reputation” enhances the firm's transactional capacity; a “bad reputation” has negative consequences and a downside impact on the value of the firm to stockholders. Therefore, the risks generated by reputation can prove to be opportunities as well as threats. In fact, subjective and multidimensional approaches (consumer, product and situation characteristics) evidence that:

-

The concept of reputation is very broad and considered an intangible asset. The management of risks linked to reputation offers therefore long-term protection for brands.

-

Brands are everyone's business in the firm and the same applies to managing risk to reputation. The management of inherent risks is transversal in essence.

-

Reputation building is a long-term effort, a trust base on which the firm's image is forged and organized.

Ever since the research conducted by Bauer (1960), Footnote 18 most marketing researchers have concentrated their efforts on explaining the relationship between factors of perceived risk. They also approached the problem of the factors explaining the elements of risks but without much consideration for the concept of reputation.

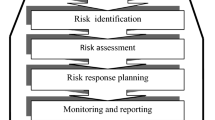

However, if managing risks to reputation is to be efficient, the first step is to identify those risks. One can manage only what one knows. Therefore, a formal brainstorming exercise should be conducted to identify what makes the “uniqueness” of the entity. Indeed, by keeping in mind the first hypothesis above, it is vital to mitigate the risks inherent to the firm's core competencies if one is to manage effectively the risks to reputation.

The Main Drivers of Reputation

If reputation risk is “any action, event or circumstance that could adversely or beneficially impact on an organization's reputation”, the drivers of reputation, and sources of potential risk, need to be identified, analysed and managed. As reputation is most often considered “a collection of perceptions and opinions, past and present, about an organization which resides in the consciousness of its stakeholders”,Footnote 19 it appears absolutely necessary to get a better grasp on the main drivers. The authors accept the hypothesis that a good reputation relies on achieving alignment between:

-

An organization's goals and values;

-

Its conduct and actions;

-

The expectations – and experience – of its stakeholders.

To penetrate better the construction of a reputation, it is therefore useful to understand the individual's judgment criteria. Fortune magazine publishes every year a poll of 8,645 individuals on their vision of the concept of reputation. Included are 351 companies from 70 industry groupings in the U.S. and 30 industries globally with revenues in excess of eight billion dollars. The consulting firm Hay Group sends a questionnaire to executives and directors in those firms and asks them to rank the companies on a scale from 0 (poor) to 10 (excellent) with different questions dealing with reputation. The average of the scores is then used for country and industry rankings. The drivers tested are an array of qualitative attributes such as: ability to attract and retain talented personnel, quality of management, social responsibility to the community and the environment, innovativeness, quality of products and services, wise use of corporate assets, financial soundness, long-term investment value, and effectiveness in doing business globally.

The results for the year 2005 in the insurance industry are summarized in Tables 1 and 2 below, the first one for life and health insurance companies and the second for property and casualty. These results must be read with caution as the respective weights of the factors are subject to personal views. However, the data, when consistently collected over time, provide meaningful respective rankings.

The most striking result is that most of the globally known companies do not appear on the list of the first 10, with the exception of CHUBB, but they are strongly established brands in the U.S. The second conclusion is that the leaders seem to be ranked high for most of the eight drivers. In life and health, Northwestern is ranked first in all but innovation whereas in property and casualty Berkshire Hathaway is first in five, second in two and third in one. The consistency of the ranking is found more or less throughout the list which may call into question the independence of the different factors or drivers and whether the overall “opinion” of the company is not then reflected in the appreciation for each individual driver. That explains why, in the final score, the range is quite wide in both categories.

Jean-Pierre PiotetFootnote 20 believes the main attributes of reputation to be: financial strength; financial morality; company's success; core know-how; quality of management; quality of strategy; combativeness; innovativeness; reference on home market; and quality of communication (the latter, he considers a minor attribute). As can be seen, this list, although different, is basically consistent with the drivers used in the poll mentioned above.

According to Corporate Reputation Watch (CRW) conducted by Harris Interactive following Hill and Knowlton's initiative, this annual surveyFootnote 21 of global management on business reputation issues shows that for nine out of 10 executives, reputation is an important element in the overall firm's strategy. However, the level of the assessment or formal measure remains limited. Some trends regarding the situation in France as compared to the international picture can still be tentatively drawn. French executives tend to be:

-

Less sensitive to the impact of the chairman or CEO's reputation on the firm's reputation.

-

More sensitive to leadership style as a means of promoting their firm's reputation.

-

Less sensitive to the Internet risk on their firm's reputation (spreading rumours).

This study also demonstrates that corporate leaders have overcome their initial misgivings about the potential administrative and financial burdens of complying with the requirements of the Sarbanes-Oxley legislationFootnote 22 applying to companies listed on exchanges in the U.S. They demonstrate a clear link between corporate reputation and customer attitudes, ranked first, just before “the ability to generate additional sales”.

To verify these results, the authors of this paper have conducted a survey limited to a selected number of insurance and reinsurance executives using questions derived from previous studies. Of the 20 questionnaires sent, 12 were completed and returned. Although the responses represent the opinions of the individuals rather than corporate vision, suffice to say that we received answers from the following groups: ACE, AGF, ALLIANZ, AXA, CHUBB, CNA-EUROPE, GERLING, IF Assurances, Munich Re, XL GROUP, and ZURICH. The respondent group is obviously small and the results do not lend themselves to hasty generalization. However, the position and experience of the respondents in the insurance industry as well as the visibility of their respective institutions give credit to the main trends that can be inferred from their answers.

Whereas 83 per cent of the respondents believed reputation to be a key factor in reaching their company's strategic objectives,Footnote 23 only 16 per cent have formalized quantification processes (metrics) to measure and monitor their company's reputation. Most of them (58 per cent) use informal information and published rankings to measure it. For 75 per cent of the interviewed directors, the key drivers are “claims handling and insured satisfaction” and “financial soundness.” These two drivers seem really essential, because they come to the front of the ranking by individuals asked to rank the same drivers on a severity scale. The close runner up “key drivers” are “ability to attract and retain best talents”, “cover extension and quality” and “effectiveness in doing business globally.” Although it is very popular with the media, “sustainable development (environment and future generations)” was not even once “ticked.” It may be that the insurance executives do not feel directly concerned because they represent a service industry.

Customers appear to be the principal stakeholders in influencing a firm's reputation, since it is recognized as important by 83 per cent of the respondents. The second most important stakeholder appears to be the firm's personnel: 58 per cent of the respondents view the personnel as “very important.” The CEO's reputation is also considered as “very important” by half of the sample and “moderately important” by one third; on the other hand, most of them consider the choice of a successor as “very important.” The impact of “stockholders” and “public officials” is not so clearly recognized. Media are not perceived as important, but that may be cultural: most respondents are French and media are generally considered as not very trustworthy in France. “Trade unions” (50 per cent “moderately important” and 42 per cent “no impact”) and “plaintiff attorneys” (42 per cent “very important” and 58 per cent “moderately important”) are never classified as “essential.”

Clearly, the Internet is not perceived by the present generation of industry leaders as an essential determining factor for a firm's reputation. Whereas 42 per cent classify it as “very important” and 42 per cent as “moderately important,” 75 per cent say they do not monitor “blogs” or forums. These answers should be qualified since most firms consider Information & Communication Technologies (ICT) as a serious matter, although it often appears they do not know how to take full advantage of their possibilities. Furthermore, economic intelligence consultants have recently started offering services to monitor open information sources and the availability of such services may soon change the understanding of the whole field by directors and executives.

Our questionnaire offered the opportunity for the respondents to add their own thoughts on reputation. Some of the comments are extremely enlightening:

-

“The instability of employment, the ever more demanding output per person, together with an intense reporting tends to create a society where it is more important to conform than to be true to oneself. In the service industry particularly, reputation rests heavily on professionalism. Professionalism is hard to maintain when the workload consists mainly of reporting and self-promotion so that colleagues and bosses know what one has done to fulfill internal needs. The hazard is that the very essence of a profession, that is, serving the community and enhancing reputation, is impaired by heavy management structures, keen on pleasing stockholders rather than customers.”

-

“Satisfying in the same time shareholders', financial analysts' and policyholders' (sometimes contradictory, sometimes complementary) expectations is becoming more difficult everyday. With ever growing information and communication flows, rating agencies and financial analysts have gained a key position in establishing corporate reputation in the insurance industry. For their part, reinsurers have a duty to keep the right balance between maximizing shareholders' value AND satisfying most of the needs of their ceding companies. In fact, a positive appraisal of the company by both groups is essential to its corporate reputation and to its future success.”

The survey results confirm quite closely what is shown in Figure 1 reproduced from Jenny Rayner's Managing Reputational Risks.Footnote 24 Reputation is clearly a composite asset that derives its value from all the acts and positions that the organization takes with its stakeholders and its ability to meet or exceed the expectations of all of them, from the owners who expect long-term financial performance and transparency, the staff that must be proud of their achievements, and the partners (customers and suppliers) that are confident in the delivery of promises, even beyond contractual obligations. Also the society at large expects compliance with rules and regulations, and social responsibility. But it is in a time of crisis that the officers and staff can prove able to cope and ride out of a storm, whatever the cause.

Figure 1 looks at reputation as an opportunity if the parts are played well with all the stakeholders. There is another side to the same coin, a downside to the same concept of “composite asset.” More than risks that would be directly derived from reputation itself, most risks to reputation appear as “metarisks.” The introduction of this concept stresses the fact that threats to reputation may stem from lapses in any domain of operations in all the firm's activities. Figure 2 illustrates this concept through a series of scenarios pertaining to the same elements introduced as drivers for the opportunity side.

From Figure 2, it is clear that one common factor underlying all the major threats to reputation is the way in which the firm understands its duty to the society as it is clearly dependant on its social licence to operate.

Corporate Social Responsibility versus Corporate Reputation: Are the Generated Risks Linked?

Reputation is patiently built on the history and the culture of the firm; therefore, deontology, corporate social responsibility, ability to internalize the concept of sustainable development, financial health, global strategy, and integrated risk management are among the key elements. However, even in the list given here, the importance of each of them in building stakeholders' trust varies substantially. Corporate social responsibility is surely one of the visible drivers of reputation and, at the same time, on its own merit a constituent of the moral and financial patrimony of the firm and a source of professionalism, although an intangible asset. It is all the more important in the insurance industry where policyholders must trust that they will be fairly treated at a time when they go through difficulties, i.e., when they incur a loss and file a claim.

The fall of the Berlin Wall and the ensuing demise of Communism in Eastern Europe seemed to have ensured final victory for the liberal economy model. However, it seems to have prompted a wave of laissez-faire in the executive suites where even the directors and shareholders interests have been apparently all but forgotten or, at best, put second to the executive remuneration packages. It is generally accepted that, possibly under public pressure, towards the end of the last decade of the twentieth century and since the beginning of the twenty-first, firms have become more and more conscious of their responsibilities be they economical, environmental or even societal. Is this myth or reality and if true could the reasons be unearthed?

Charles Fombrun and his colleagues have tried to understand why industry leaders allocated resources to “doing good”,Footnote 25 which seems a direct challenge to traditional management wisdom requesting that all efforts be directed to compressing the costs all along the supply chain. One of the two explanations for such an attitude reinforces the concept of “reputational capital,” as it implicitly aims at mitigating “reputational losses.” These authors show that “the activities that generate corporate social performance (…) affect the bottom line via its stock of ‘reputational capital' – the financial value of its intangible assets” and that “corporate citizenship is a strategic tool that companies can use to manage reputational risk with stakeholder groups.” At the end of the day, what is expected or planned through the management of the corporate social involvement is an improved performance of the firm and an enhanced competitive edge.

The spread of such an attitude of laissez-faire among directors and officers worldwide seemed at first to be the unavoidable result of the process of economic globalization. However, the awakening of consumers to their specific needs and expectations could result in a logic of differentiation of national activities within an internationally open economic field so long as the players entering the same market are few. Then the imperative of external growth might lead to redeployment of the firms' global strategies, whereby social responsibility becomes a competitive factor.

However, many governments do not trust that the forces of the market alone will lead to transparency and ethical behaviour. The U.S. Congress is currently (May, 2006) conducting hearings on “title insurance” where representatives have used words such as “kickback,” “price gouging” and “transparency of price components” that sound all too familiar to the ears of insurance professionals. On a more universal level, for instance, the federal government in the U.S., prompted by the Enron debacle, enacted in the Summer of 2002, one year later, the Sarbanes-Oxley act which requires the CEO and the CFO of all companies listed on an exchange in the U.S. to certify the sincerity of their financial statements with the Securities and Exchanges Commission (SEC), the regulatory body for the financial markets in the U.S. The act rests on three basic principles: accuracy and availability of information, individual responsibility of all managers and independence of the auditors. It is clearly intended to increase the “corporate responsibility” of all firms so as to better protect shareholders with the ultimate objective of restoring their trust in the market. This has resulted in the creation of new positions in many firms, and especially in financial institutions, to ensure conformity with all legislation and regulations, and with a clear focus on legal risk management, specifically by directors and officers potential criminal liability. These positions bear different names and cover different domains; they are “compliance officer,” “ethics manager,” “chief risk officer,” etc. It is not enough today to communicate on risk, directors and officers must make sure that effective and robust processes are designed and implemented to manage all risks in an integrated fashion; some call it a holistic approach. Furthermore, communication on risk cannot be limited to press releases polished by the PR department, “communication (on risks) is an interactive process of exchanges of information and opinion (with the various stakeholders) involving multiple messages about the nature of risk and risk management”.Footnote 26

The link between corporate governance, risk management and reputation has been elusive for some time but it seems that the wake up calls have been numerous with financial scandals, terrorist attacks, natural event-induced disasters and technological catastrophes creating an unending chain of reminders of the complexity of the modern economy. Nobody now can ignore that long term development rests on a rational balance of risks, threats and opportunities, for their own merits and as a whole, to enhance the use of resources not only for this but also for future generations.

Most of the legislation and recommendations on corporate governance in Europe (U.K. with Turnbull, Cadbury and their follow-up, France with recent legislation NRE and FSF) and in the U.S., as well as South Africa (King 2) and Australia tend to achieve two goals: transparency and accountability. This is achieved in particular through the recruitment of non-executive board members whose responsibility is to represent the shareholders' interest but also society's at large. Furthermore, most codes or legislation recommend that the audit, risk management and remuneration committee be constituted only of non-executive or independent board members.

The insurance industry has learned the hard way the impact of a bad reputation earned through unethical behaviour. The experience in the fall of 2004 with the Spitzer investigation has shaken the foundation of our business model, at least as far as the channels of distribution are concerned. Whereas it is clear that contingent commissions were not illegal, the breach of trust between company executives and their broker has been shaken. The whole industry has suffered. Has the trust been restored among the three players, insurer, broker, risk-manager, in the “insurance game”? Many have settled back and continue to do business as usual. What remains to be seen is the latitude that risk managers will have with their boards in the choice of placement and intermediaries. A panel of industry leaders gathered for the Risk and Insurance Management Society (RIMS) conference in Honolulu in April, 2006 evidenced that the trust is not entirely restored as risk managers “still expect the gains on ‘contingent commissions’ to be passed on to them in form of premium reductions.”

A prominent voice in the risk management community continues to stress the vital role of holistic risk management: “I maintain the primary goal (of risk management) must be that of building and maintaining trust, the confidence that various stakeholders have in any organization, be it governmental, non-profit or corporate. We spend far too much time and energy thinking about costs, or profits, or shareholders, and thereby dilute our effectiveness even as we satisfy the number crunchers. Trust is in especially short supply in the area of financial services in which blatant and continued conflicts of interest have eroded the very condition that is essential to this marketplace.”Footnote 27

One of the keys to governance is learning from the past and in that respect the risk manager of Sunderland in the U.K., David Francis, likes to stress, “Never make the same mistake once”. In fact, he means that in most major disasters, there was a dress rehearsal in which all the “reason” holes were not aligned by happenstance. Therefore, good governance and good risk management command one to take a careful look at near misses that may be the warning signal sent by “nature.”

However, some might debate the value-adding impact of the whole risk management exercise in reaching post-loss objectives other than survival. It will require investing resources that could be put to more productive use. This could be true without the introduction of an essential concept: resilience. That is the ability of a business to survive and grow even in the most excruciating circumstances thanks to the built-in capacity to react positively even when “bad” surprises strike. It is also the capacity of the leaders to turn the worst threats into opportunities by demonstrating their ability to take the boat to a safe harbour even in the worst seas. And this will accumulate a “trust fund” with the financial and investors' community that should endure through the next difficult time.

Governance is about transparency and being open to the needs of the environment in which the firm operates, including the need for safety and stability, moving from a closed system to an open system integrated in a global network. The main characteristics are illustrated in Table 3 below inspired by Larkin.Footnote 28

The risks that are quantifiable in financial terms still remain the focus of too much attention in many corporations, whereas “there is an emerging consensus among governments, regulators, investors and other stakeholders around the globe that shareholders are just one of a number of stakeholders groups whose interest and concerns need to be taken into account if a business is to flourish and enjoy long term success”.Footnote 29 The importance of governance can never be overestimated. Figure 3, taken from Jenny Rayner, illustrates the relationship between governance, transparent disclosure and reputation through the establishment of open channels of communication with all stakeholders. However, the potential conflict between economic intelligence and transparency should never be underestimated, especially with the promotion of “open source intelligence” which allows competitors to decipher strategic plans through the information published in different media.

Conclusion

“In the U.S. the CEO is king; chief executives are the people who heroically run the world virtually unquestioned and with little regard for the board as a significant balance of power in the organization. However, the pervading sense of corporate greed and paucity of transparent governance is eroding investor confidence and, crucially, wider public trust”.Footnote 30

These words echo a time that is not very far in the past and possibly still very much alive in all economic domains where no legislation imposes a more transparent management style. Could it be that ethics, sustainable development and social responsibility, as commonly mouthed by those in charge, may well prove nothing more than good intentions? Could reputation be another fashionable concept that lacks a generally accepted content to give it reality? There is no denying its “financial value” as is clearly evidenced by the stock prices of the most recognized names in their markets. Clearly, the more “trust” that is involved in a transaction, the more valuable is the reputation that affects the choice of partners for a potential future benefit in exchange for a real cash payment today. In other words, the insurance industry relies heavily on reputation for its transaction between professionals as well as with the non-professional insured.

It is tempting, therefore, to include some tips for industry leaders inspired by both Jenny Rayner and Judy Larkin. They are divided into four areas that address the need for an ongoing process to assess and mitigate risk to reputation as well as enhance the opportunities that can arise from the trust enjoyed with stakeholders. They stress the impact of leadership in the definition of values and installing the right controls to enforce these values through strategic goals as well as daily actions by all those associated with the organization.

Good practice in responding to reputational risks

-

Utilizing all available information (e.g., employee/client/supplier surveys, investor questionnaires, stakeholder dialogue, web activity)

-

Lateral thinking to establish useful controls and early warning indicators

-

Turning reputational threats to competitive advantage

-

Identifying and leveraging opportunities

The top team's role is vital in:

-

Communicating the vision and values

-

Setting the tone/organizational climate

-

Establishing policies and procedures to guide behaviour and decision making

-

Using outputs from risk management/stakeholder dialogue as a foundation for future strategy development

-

Ensuring the risk management process embraces reputational and social responsibility issues

-

Deciding how much risk the organization should tolerate (“risk appetite”)

-

Striving to maintain exposures within those limits

-

Ensuring that everyone in the organization understands what level of risk they are empowered to take on behalf of the organization

Planning for the future

-

Anticipating shifts in stakeholder expectations and in regulatory requirements: acting and reporting accordingly

-

Seeking to differentiate yourself from others in the same sector

-

Anticipating and limiting collateral damage

-

Having reputational risk on the board's agenda

The benefits of positive reputation risk management

-

Builds stakeholder trust and confidence

-

Maintains the “social licence to operate”

-

Attracts investment

-

Boosts customer and supplier loyalty

-

Reduces regulatory intervention

-

Creates barriers to entry

-

Facilitates premium pricing

-

Enables recruitment/retention of the best

-

Provides a store of reputational capital that protects against future crises

All the recommendations and expectations listed above can be summarized in one simple commandment that stresses the link between trust and reputation: promote a virtuous circle of reputation building (Figure 4).

To be successful and sustainable, that is, to achieve a sound level of resilience, any business needs to enjoy the trust and confidence of all its stakeholders and that can be achieved only when its actions are in harmony with its words. In practice, that requires integrating into the overall strategy the key elements of trust building: corporate governance, risk management, corporate social responsibility and reputation management. At a time when all practitioners, directors and officers have become aware of the need for a global corporate risk management strategy, there seems to be a mushrooming of new “silos” in risk management such as sustainable development risk management, procurement risk management, marketing risk management, etc. Therefore, reputation risk management may well prove to be the cornerstone to the desired integration provided executives and board members keep in mind that a reputation must be built both “inside out” and “outside in.” Furthermore, as one of our respondents stressed: “corporate reputation serves as a reservoir of goodwill to draw upon when challenges and difficulties arise.” More than in any other industry, the insurance and reinsurance executives must strive to build an authentic business: “A defining feature of an authentic business is that its profound and positive purpose shines through every aspect of what it does, whether paying invoices (claims), parting with a member of staff, or presenting at a conference”.Footnote 31

Ethical conduct is the core ingredient of trust, hence of reputation. As the insurance industry experienced in the fall of 2004, individual lapses are always possible. Therefore, we must stress how important it is for any organization to prepare for a disaster, should it strike. In a recently published book on corporate integrity the authors stress that: “As we found with hurricane Katrina, being unprepared can cause a disaster that is far greater than the damage caused by the underlying event. The ethical disaster risks facing organizations today are significant and the reputational damage caused can be far greater for those companies that find themselves unprepared…Although we cannot predict an ethical disaster, we can and must prepare for one.”Footnote 32

The final word we borrow from Madeleine Albright, former Secretary of State of the U.S. While addressing the subject of risks of war, terrorism and deadly pandemics and reflecting on her work during the Clinton administration at a Marsh breakfast during the RIMS convention in Honolulu on April 25, 2006, she gave this essential piece of advice to risk management and insurance leaders: “Decisions are only as good as the information you have…Although the crisis for which you prepare may never happen, one will happen…Being prepared for a crisis is never a waste of time.”

Notes

“In a survey of 269 senior executives, reputational risk emerged as the most significant threat to business out of a choice of 13 categories of risks, (…) a survey of which 36 per cent are from companies in the financial services sector”, in The Economist Intelligence Unit (2005).

More precisely, Simon (1951) was the first economic author to refer to the concept of reputation for its “analyse de la relation d'emploi”. Reputation is what makes credible both the promises and threats uttered by an employer. Losing one's reputation results then in the inability to hire new staff and to offer higher wages to attract others.

(Its name is derived from common sense.) Any couple of gains such that both are positive and less than the monopolistic profit can lead to an equilibrium, if and only if the future is granted sufficient importance.

The consumer is assumed to be rational, and makes his choices on the basis of the maximization of his preferences (represented by a utility function under the form of indifference curves) under a budget constraint (linear constraint), which comes down to solving a maximization problem under constraints.

Reputation Value Added.

Kraft-Jacob-Suchard, food subsidiary of the Philip Morris Group.

President of the French “Observatoire de la Réputation”

• In all, 405 telephone interviews in Europe,• 600 questionnaires filled in the U.S.A. and Canada• error margin evaluated at 5 per cent of sample size

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002, in response to corporate scandals such as Enron, is aimed at protecting investors. It has created many new obligations and involves significant penalties for non-compliance. It covers areas such as: financial reporting and internal controls, insider trading, personal loans, and penalties.

According to Hill and Knowlton: 86 per cent of executives polled in France/94 per cent in the U.S.A.

Australian risk management guidelines HB 436:2004.

Brewer et al. (2006, p. 3).

References

Akerlof, G. (1970) ‘The market for lemons: Qualitative uncertainty and the market mechanism’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 84: 488–500.

Bauer, R.A. (1960) ‘Consumer behavior as risk taking”, in R.S. Hancok (ed) Dynamic Marketing for a Changing World, Chicago, IL: American Marketing Association, pp. 389–398.

Belva, K.F. (2005) How it's difficult to ruin a good name: An analysis of reputational risk, CISSP, 19 September.

Brewer, L., Chandler, R.C. and Ferrell, O.C. (2006) Managing Risks for Corporate Integrity: How to Survive an Ethical Misconduct Disaster, Belmont, CA: South-Western Educational Publishing.

Chemmanur, T.J. and Fulghieri, P. (1994) ‘Reputation, renegotiation, and the choice between bank loans and publicly traded debt’, Review of Financial Studies 7 (3): 475–506.

Crofts, N. (2005) Authentic Business: How to Create and Run Your Perfect Business, Oxford: Capstone Publishing Company.

Diamond, D.W. (1991) ‘Financial intermediation and delegated monitoring’, Review of Economic Studies 51: 393–414.

Ducarroz, C., Scarmure, P. and Sinigaglia, S. (2003) Tintin au pays des enchères: Information sur la qualité et réputation des vendeurs, Actes du XXème Congrès AFM, 6&7 mai 2004, St Malo (France).

The Economist Intelligence Unit (2005) Reputation: Risk of risks, EIU White Paper, December.

Fagart, M.C. and Kambia-Chopin, B. (2003) Aléa moral et Sélection Adverse sur le marché de l'Assurance, working paper CREST/THEMA.

Fombrun, C.J., Gardberg, N.A. and Barnett, M.L. (2000) ‘Opportunity platforms and safety nets: Corporate citizenship and reputational risk’, Business and Society Review 105 (1): 85–106.

Fombrun, C.J. (2005) ‘A world of reputation research, analysis and thinking – building corporate reputation through CSR initiatives: Evolving standards’, Corporate Reputation Review 8 (1): 7–12.

Graham, P. and Fearn, H. (2005) ‘Corporate reputation: What do consumers really care about?’, Journal of Advertising Research 45 (3): 305–313.

Kloman, F. (2005) Risk Management and Monty Python, London: Institute of Risk Management Lecture, October 10.

Kreps, D.M. (1990a) Game Theory and Economic Modelling, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kreps, D.M. (1990b) ‘Corporate culture & economic theory”, in J.E. Alt and K.A. Shepsle (eds) Perspectives on Positive Political Economy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 90–143.

Larkin, J. (2003) Strategic Reputation Risk Management, Basingstoke, U.K.: Palgrave Macmillan.

McDonald, C. and Slawson, V. (2002) ‘Reputation in internet auction market’, Economic Inquiry 40: 633–650.

Menilk, M. and Alm, J. (2002) ‘Does a Seller's e-Commerce reputation matter? Evidence from e-Bay auctions’, Journal of Industrial Economics 50 (3): 337–349.

Rayner, J. (2003) Managing Reputational Risk: Curbing Threats, Leveraging Opportunities, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Resnick, P. and Zeckhauser, R. (2002) ‘Trust among strangers in internet transactions: Empirical analysis of e-Bay's reputation system”, in M. Bay (ed) The Economics of the Internet and the e-Commerce, London: Elsevier, pp. 127–157.

Rothschild, M. and Stiglitz, J.E. (1976) ‘Equilibrium in competitive insurance markets: An essay on the economics of imperfect information’, Quarterly Journal of Economics 90 (4): 630–649.

Sami, H. (2004) Firm's Financial Distress and Reputational Concerns, working paper.

Schelling, T.C. (1960) The Strategy of Conflict, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Simon, H.A. (1951) ‘A formal theory of the employment contract’, Econometrica 19: 293–305.

Standifird, S. (2001) ‘Reputation and E-commerce: e-Bay's auctions and the asymmetrical impact of positive and negative rating’, Journal of Management 27: 279–285.

Standifird, S. (2002) ‘Online auctions and the importance of reputation type’, Electronic Markets 12 (1).

Tirole, J. (1993) A theory of Collective Reputations, mimeo.

Further Reading

Anderson, D.R. (2006) ‘The critical Importance of Sustainability Risk Management’, Risk Management Magazine 53: 66–74.

Cagan, P. (2006) ‘On finding linkages: corporate governance and operational risk’, The John Liner Review 19 (4): 7.

Gaultier-Gaillard, S. and Louisot, J.P. (2004) ‘Diagnostic des risques’, in AFNOR (ed) La Plaine, St-Denis.

Louisot, JP. (2005) ‘100 questions pour comprendre la gestion des risques’, in AFNOR (ed) La Plaine, St-Denis.

Louisot, JP. (2004) ‘Managing intangible asset risks: Reputation and strategic redeployment planning’, Risk Management: An International Journal 6 (3): 35–50.

Nelson, A. and Etue, D. (2006) ‘Reducing the risk of information leakage’, The John Liner Review 20 (1).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gaultier-Gaillard, S., Louisot, JP. Risks to Reputation: A Global Approach. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 31, 425–445 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.gpp.2510090

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.gpp.2510090