Abstract

Translation technology is nowadays widely used by many language service sectors, and translation technology training is offered by many universities and institutions around the world. However, the effectiveness of translation technology training is yet to be explored. To fill this gap, we conducted a questionnaire survey of 385 Master of Translation and Interpreting (MTI) students in China to understand the general trends in their reception and perception of their translation technology courses. In order to probe into the student’s experience of taking these courses, we further interviewed 8 of them. All the interviews, semi-structured to allow for both structured and free expression, were recorded and transcribed verbatim for analysis. The Kirkpatrick model was used as the evaluation framework of training effectiveness. Results show that some students felt that the training was quite effective and it enabled them to gain the knowledge of computer-assisted translation tools. However, some felt less positive about the effectiveness of current training of translation technology and cited various challenges they encountered in their learning. All the findings and recommendations thereof will be discussed. It is hoped that the findings will contribute to our understanding and improvement of translation technology training in future programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Translation technology has witnessed rapid development over the past decade, thanks to the advances in Artificial Intelligence, Big Data and Cloud Computing. Most translation teachers and students have gradually come to terms with it. Today many people are convinced that translators will be better off embracing translation technology than resisting it (Bowker 2023). In fact, translators can hardly survive in the market today if with little knowledge or no skills in translation technology (ibid.). According to the survey conducted by Wang et al. (2018), over half of the MTI programs in Chinese universities have begun to offer one or more translation technology courses, with the aim to prepare their students in translation technology, despite formidable challenges such as shortage of qualified teachers, availability of funding and facilities, and translation students’ general lack of training in computer skills.

Although previous research has discussed translation technology training from various aspects, such as pedagogical approaches and methods (Alcina et al. 2007; Olvera Lobo et al. 2007; Nunes Vieira et al. 2021), curriculum and syllabus design (Mellinger 2017; Su 2021; Sánchez-Castany 2023) and translation technology competences and skill sets (Rodríguez-Inés 2010; Gaspari et al. 2015; Pym 2013), relatively few studies have systematically investigated the effectiveness of translation technology training as perceived by students. Furthermore, most of the limited studies that have examined the effectiveness of translation technology training have focused on a single teaching context or a specific aspect of effectiveness (e.g., Rodríguez-Castro 2018; Sycz-Opoń and Gałuskina 2016; Doherty and Kenny 2014) (a more detailed discussion of these studies appears in the “Effectiveness of translation technology training” section). A thorough discussion of training effectiveness as seen by students remains to be carried out.

Evaluating training effectiveness of translation technology is vital to the curriculum design and methodology of teaching translation in general and translation technology in particular. It is therefore the purpose of this article to evaluate the effectiveness of translation technology training in order to improve training programs and courses on translation technology. For that, we conducted a questionnaire survey of 385 students of translation and interpreting majors in China and interviewed 8 of them. We adopted the Kirkpatrick model of training assessment (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick 2006) as the framework for evaluating the effectiveness of translation technology training.

Effectiveness of translation technology training

In this study, translation technology is understood as computer-assisted translation (CAT) (see O’Brien and Rodríguez Vázquez 2020 for a similar idea), which refers to “a large array of computer tools that help translators do their jobs” (O’Brien and Rodríguez Vázquez 2020, p. 264). Accordingly, translation technology training is defined as the process of teaching and learning the knowledge and skills that students need for using translation technology or computer-assisted translation, including translation memory, terminology extraction and management, and machine translation post-editing.

It is acknowledged that translation technology training has become an essential part of the translation curriculum, but the effectiveness of translation technology training remains to be explored. Rodríguez-Castro (2018) discussed a specific case study of a postgraduate course on computer-assisted translation to illustrate the principles of course design of translation technology. One of the most important principles was to incorporate professional skills into the course. The author also took account of the learning outcomes of the course, which could be roughly understood as learning effectiveness, by assessing students’ translation performance and their perceptions on the course. The results showed that most students believed they had acquired the skills of using translation technology, but some were dissatisfied with their abilities to work in a translation project. Sycz-Opoń and Gałuskina (2016) incorporated the content of machine translation (MT) and the self-built MT evaluation protocol into a translation course. The evaluation protocol was designed to help students spot potential MT errors. The authors further investigated the effectiveness of the MT training by analyzing students’ evaluation of the MT classes. Results showed that most students were positive about the use of MT and the MT evaluation protocol in machine translation post-editing tasks.

Other scholars focused on one particular indicator of the effectiveness of translation technology training. For instance, one indicator of training effectiveness is self-efficacy. In the context of translation technology training, self-efficacy is students’ beliefs about their capabilities to use translation technology. Doherty and Kenny (2014) used self-efficacy to evaluate the effectiveness of a syllabus on statistical machine translation (SMT) from a course module of translation technology. Following a detailed description of the teaching content and assessment methods of the SMT syllabus, the authors invited students to fill in a self-efficacy survey in order to understand their confidence in using SMT, which could indicate the effectiveness of the SMT syllabus. They found that the SMT training enhanced students’ confidence in managing translation workflows involving SMT, which suggested that the SMT training was effective in making students believe that they could applying SMT in translation tasks.

Drawing on the Kirkpatrick model of training evaluation, Samman (2022) is one of the few studies that systematically examined the effectiveness of a 4-week machine translation post-editing (MTPE) training. The Kirkpatrick model contains four levels, namely the levels of reaction, learning, behavior and results (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick 2006) (a more detailed discussion of the four levels appears in the “The Kirkpatrick model of assessing training effectiveness” section). Specifically, Samman (2022) investigated the training effectiveness about MTPE (the reaction level), total translation time (the behavior level), and the quality of translation products (the results level). The results showed that MTPE training was most helpful in developing students’ positive attitudes towards MTPE and in increasing translation efficiency.

Overall, these studies investigated a specific course, task, or project concerning translation technology in great detail. They served as useful and valuable examples for teachers and trainers of translation technology. However, these studies fell short of an in-depth discussion of the effectiveness of translation technology training as a whole, and the construct of effectiveness was not fully or clearly defined (except for Samman 2022). Therefore, the present study aims to carry out a comprehensive investigation of graduate-level translation technology courses offered at different institutions and universities in China, by surveying the students’ perspectives with a questionnaire and later interviews on the effectiveness of the training. We have chosen to adopt the Kirkpatrick model as our framework to define and comprehensively evaluate the effectiveness. The data from the questionnaire and the subsequent interviews enable us to develop a comprehensive understanding of the effectiveness of translation technology training in a wide range of teaching contexts.

The Kirkpatrick model of assessing training effectiveness

Evaluations of effectiveness of translation courses or training programs have been largely aimed at investigating students’ satisfaction, engagement, knowledge and skills gained from training, perceived challenges and difficulties (e.g., Li 2013; Li et al. 2015; Szarkowska 2019) or translation performance and products (e.g., Nunes Vieira et al. 2021). However, their findings are sometimes hard to compare and conclude due to lack of powerful evaluation frameworks or models for analysis. In fact, only a few studies have adopted evaluation frameworks or models to structure their investigation of effectiveness in translation training (e.g., Mahasneh 2013; Carsten et al. 2021; Su et al. 2021). The CIPP (context, input, process, product) evaluation model (Stufflebeam 1971), the holistic TEL (technology-enhanced learning) evaluation framework (Pickering and Joynes 2016) and the Kirkpatrick four-level evaluation model (Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick 2006) were often adopted.

Mellinger and Hanson (2020) suggest that in data-based empirical research, a theoretical foundation should be established to define the construct under study before any consideration of indicators that can reflect the construct. In the present study, the construct under study is effectiveness in translation technology training. We adopted the Kirkpatrick evaluation model in our investigation. This model is a comprehensive and widely used approach for understanding both the outcome achievements and performance gaps of training in a variety of contexts (Alsalamah and Callinan 2021) and we have found it powerful in our evaluation of training effectiveness with a focus on the outcomes of translation technology training.

The Kirkpatrick model works at four distinct levels. First, the reaction level looks at participants’ perceptions of the training program. Then the learning level focuses on what participants have learnt, and the behavior level measures behavioral changes as a result of application of the learning. Finally, the results level examines participants’ improvement as a result of the training program. This study intends to evaluate the effectiveness of translation technology training by focusing on changes in the reaction and the behavior level. These two levels are operationalized “in a soft, qualitative way” (Burgoyne 2012, p. 1175) where students’ subjective judgments were collected with a questionnaire survey and follow-up interviews. The descriptions and operationalization of the two levels were further specified in order to accommodate the context of translation technology training (see Table 1).

Two things are worth noting. First, the descriptions of the two levels in Table 1 were adapted from Kirkpatrick and Kirkpatrick (2016). Second, students’ perceived technological competences were considered as a triangulation of students’ perceived areas of growth. Students were invited to write down their areas of growth after training in an open-ended question. Then, they were asked to rate their level of competences in a 5-point Likert scale. The use of these two data sources can ensure a more comprehensive understanding of what students have learnt after translation technology training.

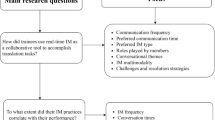

To summarize, the objective of this study is to assess the effectiveness of translation technology training in China, focusing on the reaction and learning levels of the Kirkpatrick model. This evaluation includes students’ satisfaction, perceived areas of growth resulting from the training, difficulties faced, and technological competences. Specifically, the following two research questions were used to guide the study:

-

(1)

To what extent do the students perceive the translation technology training as satisfactory? This includes their overall assessment of the training effectiveness, satisfaction with the textbooks, teaching methods, assessment methods, and their attitudes towards translation technology.

-

(2)

To what extent has the learning of translation technology taken place? This involves students’ perceived areas of growth, the difficulties encountered during training, and their perceived technological competences.

Methods

Participants

This study focused on students who had taken one or more translation technology related courses in Master of Translation and Interpreting (MTI) programs offered by colleges and universities in China. To recruit eligible participants, we contacted 60 teachers of translation technology through the educational network of Translation Technology Education Society (TTES) of World Interpreter and Translator Training Association (WITTA). Through them, we sent a web-based questionnaire to students who had taken at least one course related to translation technology. This study employed convenience sampling and snowball sampling methods for distributing the online questionnaire. The participants were 385 MTI students (332 women, 86.23%; 53 men, 13.77%) from 52 comprehensive universities and universities of foreign studies in China, with a mean age of 23 years (SD = 2.87). These universities were distributed across 23 municipalities and provinces in China. The participants of the questionnaire were made up of 216 first-year students (56.1%), 130 second-year students (33.77%) and 39 third-year students (10.13%). The research was approved by University of Macau Ethics Review Committee. All participants gave their informed consent before answering the questions.

Instruments

A questionnaire survey and semi-structured interviews were used to collect data on the effectiveness of translation technology training. The questionnaire and the interviews were conducted in 2018–2019. In light of the reaction and behavior levels of the Kirkpatrick evaluation model, we structured the questionnaire into two parts in addition to one part on the participants’ personal information (see Appendix A for the entire questionnaire). Part One, Reaction, assessed the extent to which participants found the translation technology training effective. It also measured their satisfaction with the textbooks, teaching methods, and assessment methods, as well as their understanding of the importance of learning translation technology. Students were asked to rate their perceptions on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “very ineffective” to “very effective” or “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree”. Additionally, this part included a multiple-choice question on the reasons students considered translation technology important or not important to them.

The second part, Learning, aimed to assess students’ perceived areas of growth after training, the challenges they faced during training, and their translation technology competences. Along with Likert scale questions, this part included an open-ended question to encourage students to provide detailed and meaningful answers about the knowledge and skills they gained from translation technology training.

To gain deeper insights into students’ perceptions of translation technology training, we conducted semi-structured interviews with 8 participants. These interviews served as a triangulation of the survey questions. Participants for the interviews were selected from the survey respondents who expressed their willingness to be interviewed. They represented 5 universities across 5 municipalities and provinces in China. Prior to the interviews, the students provided their informed consent.

Each semi-structured interview had three segments (see Galletta 2013). In the opening segment, we began with a statement of our research purpose, which was to understand students’ experiences and perceptions of translation technology training, and to what extent they thought the training was effective. We invited the students to freely express their overall perceptions of translation technology training. In the middle segment, we proceeded with more specific questions related to our two research questions (see Appendix B for the interview questions). In the concluding segment, we asked the students for their final thoughts and thanked them for their participation. The interviews were conducted in Chinese, the mother tongue of the interviewees, and later transcribed for analysis and translated into English for reporting.

Data analysis

We started with initial data check of the questionnaire to spot any inconsistencies and errors, as suggested by Dörnyei (2007). We then conducted a reliability analysis of the multi-item scales. Each Cronbach Alpha coefficient was above the recommended threshold of 0.70 (see Table 2), indicating that the multi-item scales in the questionnaire met the reliability requirement of internal consistency.

We adopted Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-phase process of thematic analysis to analyze the open-ended question. In Phase 1, the two researchers familiarized themselves with the data by reading students’ answers numerous times. In Phase 2, they independently coded the answers to the open-ended question, and met for discussion until the final list of the possible codes were produced. In Phase 3, the two researchers independently combined the codes to form themes about students’ perceived gains in knowledge and skills of translation technology. Phase 4 began when the researchers met for reviewing the candidate themes until the final list of the themes was drawn up. In Phase 5, the two researchers independently calculated the number of mentions of each theme. When discrepancies arose, they would meet for discussion until an agreement was reached. In Phase 6, the researchers concluded on the themes in the “Results” section.

All the semi-structured interviews, which lasted 20 to 40 min each, were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The researchers listened to each interview recording at least once and repeatedly read through each interview transcript. They identified salient comments regarding students’ perceptions of the training effectiveness (the reaction level) and their perceived increase in knowledge and skills resulting from the training (the learning level). These comments were then selected and translated into English to provide supporting evidence of the training effectiveness. Pseudonyms were used to preserve the anonymity of the translation students.

Results

Reaction

Attitudes towards translation technology

Students had a remarkable change of attitude towards translation technology after taking translation technology courses (see Table 3). In total, 73.76% (18.44 + 55.32%) of the students reported that the training helped them change their perceptions of translation technology. In total, 90.01% (48.83 + 42.08%) of the students agreed or strongly agreed that translation technology was important to all future professional translators, and felt they must acquire translation technology competence in order to become translators/interpreters or other language service providers. In total, 89.1% (44.16 + 44.94%) of the students agreed or strongly agreed that as we face the challenges posed by translation technology, the best strategy for future translators is to harness the technology and make it work for us.

When asked whether they believed that translation technology is going to replace professional translators, 79.74% (61.04 + 18.7%) of the students disagreed or strongly disagreed. Daniel (pseudonym and same afterwards) elaborated on this point:

I don’t think translation technology will replace translators. In order to improve the output quality of machine translation, we usually need to pre-edit the source text to make the machine easier to read and translate, and we also need to post-edit the direct output produced by machine translation. Translation technology just changes the way we translate.

However, the students in the interviews felt that as they enjoyed the convenience and efficiency of machine translation, they found it difficult to think beyond the machine translation output. They worried they would become less creative and imaginative if they kept post-editing machine translation output instead of translating from scratch. A comment made by Amy illustrated this worry:

When I need to translate a source text, I usually put it on a machine translation engine. I am impressed that most of the sentences are well translated and I just need to make some minor modifications. As I am increasingly dependent on the machine translation output, should I be worried that my expressions would become machine-like?

Interestingly, the result of Question 5 showed that nearly half of the student (48.05%) reported that they would not become professional translators in the future, but still the training made them see the need to enhance their technological competence in order to prepare themselves better for any career other than a professional translator or interpreter.

Overall perceptions of training effectiveness

Students’ overall perceptions of training effectiveness were presented in Table 4. In total, 38.96% of the students considered the translation technology training effective, and 7.53% considered it very effective. However, slightly more than half of the students felt less positive. In total, 43.12% of the respondents felt the training was neither effective nor ineffective, 7.27% thought the training was ineffective, and 3.12% considered the training very ineffective.

Reactions to textbooks, teaching methods and assessment methods

We then investigated students’ satisfaction and perceived usefulness of the textbooks, teaching methods and assessment methods in order to further examine the effectiveness of translation technology training. Overall, students responded neutrally to the content of the textbooks used in their training, believing that the textbooks could be more comprehensive and updated. Students’ perception of the textbooks was shown in Table 5.

After a detailed examination of the data presented in Table 5, the following observations were made:

-

43.37% (8.05 + 35.32%) of the students felt the textbooks they used in class were short of online resources and companion websites that provide solutions manuals, supplementary materials or references for the textbook problems.

-

38.18% (5.19 + 32.99%) thought the textbooks failed to provide sufficient real-world case studies and hands-on experience to help them understand how to use translation technology in future workplace or in personal working environment.

-

Whereas 44.68% responded neutrally, 28.05% (6.75 + 21.3%) argued that the textbooks had not kept up with the rapid development of translation tools and still talked about the older versions of translation tools.

The students had a positive perception of two aspects related to the textbooks in translation technology training. In total, 53.76% (15.58 + 38.18%) reported that the textbooks systematically covered translation technology knowledge, and 61.3% (17.4 + 43.9%) agreed or strongly agreed that the textbook provided detailed operation procedures of translation tools and software.

As for the teaching methods, 69.61% (21.82 + 47.79%) of the respondents considered project-based teaching effective and very effective (see Table 6), which came out as the most effective and useful teaching method. In total, 68.83% (19.74 + 49.09%) believed that PowerPoint presentations by instructors were effective and very effective. A good number of students also showed positive perceptions of students’ in-class reports, researching local language service provider and brainstorming as teaching methods. Project contests and flipped classroom were less welcomed.

The respondents were also asked how they perceived their assessment methods in the training. In-class tests on the application of translation technology were considered most effective (22.86 + 62.6% = 85.46%), followed by class exercises and assignments (21.56 + 60.26% = 81.82%), use of online platform to monitor learning process (17.92 + 57.92% = 75.84%) and in-class presentations (14.55 + 53.25 = 67.8%) (see Table 7). Assessment methods such as open book exams, essays and close book exams were considered less effective.

Learning

Students’ perceived areas of growth

The students were also invited to discuss their perceived areas of growth after receiving the training (see Table 8 for the complete list).

In total, 66.8% of the students reported that their biggest gain in the training was their acquired knowledge of the computer-assisted tools they had learnt. Jack elaborated on this acquired knowledge:

I used to think that translation technology was equal to machine translation. Now I learnt that translation technology is not only about machine translation, it also includes all sorts of computer-assisted translation tools. I think I have a basic understanding of the prominent features and functions of SDL Trados.

Kelly added that the training helped her gain a deeper understanding of what is computer-assisted translation:

At the beginning of the training, my classmates and I thought that computer-assisted translation software was the same as Baidu translation. For example, we imagined that when we put the source texts in SDL Trados, the target texts would automatically come out. But later I found that we need to utilize the pre-imported translation memories and termbases and select a machine translation engine before we can make full use of the CAT tool.

The knowledge of translation memories and termbases was an area where most students experienced growth. In total, 44.4% of the students reported the training heightened their sense of using translation memories and termbases in the process of translation. The gained knowledge of translation memories and termbases meant the enhanced awareness of reusing previously translated texts and terms to speed up translation. For instance, David noted that students tried to make the most of translation memories and termbases after training:

I have got a basic awareness of using previously translated texts to help me translate. Now when I need to translate a new source text, I will first look for similar texts that I have translated before.

In total, 24.4% thought that they learnt the use of translation technology. Interestingly, the students in the interviews argued that translation would not be successful if they only focused their attention on technologies. They agreed technologies were important and necessary for translation profession, but they firmly believed that translators still needed to make a lot of decisions and thus should work hard to build a solid foundation in both Chinese and English. Steven elaborated on this point:

Translation memories and machine translations are not always accurate and useful. So, at many times we need to decide on the best output generated by tools and machines. I think translators’ language proficiency is the most important thing.

The students also mentioned that the training helped them improve various skills, including translation speed (20.3%), translation competence (15.8%), searching skills (9.4%), and computer skills (9.1%). However, less than 5% of the respondents mentioned acquiring knowledge and skills related to audiovisual translation and interpreting, as well as collaboration with group members.

Students’ perceived difficulties

Table 9 presents students’ perceived difficulties during translation technology training. Most students reported difficulties in relation to insufficient practices and operations of technological tools. Insufficient training in application of technology in completing translation tasks was mentioned by most students (19.22% + 48.83% = 68.05%) as the biggest difficulty. Amy made a typical comment:

Maybe the biggest difficulty I encountered in the training is lack of actual use of the tools in translation tasks. After all, the class time is limited. There are a lot of functions that need to be explored by ourselves.

Students in our interviews complained about teachers’ ambition to cover a wide range of technologies and the resulting lack of practices and applications of the tools they learnt. For example, Tom commented that:

The instructor spent too much time talking about different translation tools and little time was left for actual practices of the tools. I am not quite sure whether I can make full use of the tools in translation tasks.

Insufficient practices during class usually require more extracurricular practices with the tools. However, students did not seem to be very motivated to practice more after class to get familiar with the various functions of the tools. Daniel expressed an honest opinion on this issue:

I didn’t spend lots of time practicing the tools after class. I think one reason might be that the translation projects are usually fake. My classmates and I did not see much value of completing them.

The second biggest difficulty mentioned by the students was the lack of sufficient training cases provided by teachers, with a total of 66.49% of the respondents expressing this concern (17.92 + 48.57%). Students complained that the training sometimes only covered the basics of translation technologies and failed to provide real-world cases that could motivate them to apply translation technology in a workplace setting. For example, Tina felt that she only had a superficial understanding of translation technologies:

At times the teacher just mentioned the functions of the tools without explaining when and how they can be implemented in translation work. The training did not incorporate sufficient real-world cases and scenarios.

Another difficulty mentioned by the students was the lack of involvement of experts from language service providers in the training, with a combined percentage of 59.74% (17.4 + 42.34%). It seemed that the possibility of inviting experts in language service providers to classroom teaching would offer a huge advantage to most students, because they believed that such experts could inform them of the needs of translation markets. In total, 57.15% (14.81 + 42.34%) of the students felt the training hours were insufficient to provide in-depth learning of translation technology. Students also reported facing other challenges during the training, such as receiving inadequate guidance from teachers when dealing with difficult topics, encountering poor lab conditions, and feeling overwhelmed by overly complex training content.

Students’ perceived technological competences

Lastly, we examined to what extent the translation technology training created a positive impact on students’ technological competences. The concept of competence centers on “what translators should be able to do rather what they need to know” (Pacheco Aguilar 2019, p. 30). For ease of analysis, technological competences fall into three categories: competence of using information technology, competence of using translation technology and competence of managing translation and localization projects. Table 10 shows students’ perceived technological competences as a result of receiving the translation technology training.

Regarding the students’ competence in using information technology, their opinions were diverse. A majority of the students (57.4%) rated their competence in basic computer skills and Office operation skills as good or even excellent (47.53 + 9.87%). Approximately 39.74% considered themselves as having average competence in these areas, while only 2.86% rated themselves as inadequate or poor. However, when it came to computer programming, only 16.88 and 5.19% of the students rated their competence as good or excellent, respectively. Almost half of the students (42.6%) considered their competence in computer programming as average, and 35.33% (11.43 + 23.9%) felt that the training did not adequately prepare them for acquiring knowledge and skills in this area.

As for the competence of using translation technology, 42.07% (36.1 + 5.97%) of the students commented that they had good and excellent competence in using CAT tools after the training, but meanwhile 50.39% reported that they only possessed average competence in applying different CAT tools in translation tasks and practices. Similarly, 51.43% believed that they only had average competence in terminology management, and 49.35% thought their ability to use translation corpus and translation memories was just average. Whereas 41.29% (35.06 + 6.23%) reported good and excellent competence of post-editing machine-generated translations, 47.53% pointed out average competence of machine translation post-editing.

A similar pattern was observed in the ratings for perceived competences of managing translation and localization projects. For instance, 31.68% (25.19 + 6.49%) believed that they were competent in translation project management, However, a larger group of students (53.25%) rated their competence in this area as average.

Discussion and implications

Students’ reaction

The first research question was how the students perceived the translation technology training. Overall, we conclude that the translation technology training was slightly effective in the eyes of the students, given that as large as 43.12% felt that the training was neither effective nor ineffective (see Table 4). In general, the students in our sample can be classified as beginners in their progression of learning translation technology, as they have yet to reach a level of competence, proficiency, and expertise in this field (see Massey and Kiraly 2021). That is to say, the students in our sample had a basic understanding of the knowledge and concepts of translation technology through teachers’ instructions and lectures, and they were on the way of putting theories and concepts into practices. Hopefully this result can remind translation technology teachers that we still have much work to do in order to improve translation technology training.

It is worth noting that PowerPoint presentation by instructors was considered the second most effective teaching method (see Table 6). The students in our sample seemed to favor a large amount of guidance from teachers in translation technology training. However, recent literature shows the importance of discovery learning in enhancing the competence of using translation technology (see Nunes Vieira et al. 2021). This indicates the need for further studies on how much guidance is needed for students to reach a good level of competence in using translation technology. Also, teachers may need to consider how to strike a balance between guidance and discovery learning, especially when teaching beginners translation technology.

Students’ attitudes towards translation technology were considered to have played an important role in translation technology training (Doherty and Moorkens 2013; Koponen 2015; Guerberof-Arenas and Moorkens 2019). To summarize, students felt that translation technology:

-

Is what translation students need to master.

-

Is important for any career other than professional translators and interpreters.

-

Will not replace translators or interpreters.

-

Might harm their creativity and imagination.

These attitudes towards translation technology reflect what Pietrzak and Kornacki (2021) called “technological flexibility” (p. 10) of translators, meaning that translators are willing to try and use different technologies to meet the changes of the market needs (ibid.). Technological flexibility is an important property of translators and interpreters to achieve success in the age that emphasizes efficiency and changeability.

But students worried that relying too much on machine-translated texts might adversely affect their creativity and imagination. This kind of anxiety has been recently tested by Guerberof-Arenas and Toral (2020) and it was found that when comparing human translation without technological assistance to professional translators in machine translation post-editing, the latter tends to produce translations that are less creative. Therefore, translation technology training should emphasize skills and qualities that have not yet been replaced or will not likely be replaced by technology. Pym and Torres-Simón (2021) suggested that students “do what the machine can’t do” (p. 12) in translator training, as a way to address automation brought on by technological development in translation workflow.

In accordance with the Standards of English Language Ability, the usage of technologies in translation is important. However, translators should possess the ability to “creatively supplement the implied content of the original to imitate or recreate imagery or rhetorical devices in the translation” (MEPRC and NLSCPRC 2018, p. 116). Translation technology curriculum should attempt to strike a balance between what technologies can do and what human beings are capable of doing. For instance, translation technology training can on the one hand guide students to use technologies to help with memorization work, and on the other hand stress the importance of cultivating students’ capacity to analyze, evaluate and create translations (see Li 2022 for a detailed discussion of translation creativity in the era of translation technology).

Students’ learning

The second research question was to what extent the learning of translation technology occurred. Most of the students saw their biggest growth was the acquired knowledge of computer-assisted translation tools, followed by the knowledge of translation memories and termbases, which was closely related to the knowledge of CAT tools (see Table 8). This result was not surprising as CAT tools have been long regarded as essential parts of translation technology (Alcina 2008) and translation technology training (Bowker 2015; Rodríguez-Castro 2018; Kornacki 2018). According to Wang et al. (2018), 90.4% of the MTI programs in China that provided translation technology training offered CAT courses, so students might feel that they knew much more about CAT tools than other aspects of translation technology. This result was also encouraging because most language service companies expected their employees to be familiar with CAT tools (Wang 2019; Ginovart Cid et al. 2020; O’Brien and Rossetti 2020).

However, this growth in the knowledge of CAT tools might be no more than an indication of “knowing what” rather than “knowing how” (Pym 2013): students memorized the operational steps of the software but the ability of actually using the CAT tool in a particular translation task was not satisfactory. When asked to what extent they felt they had developed their technological competence, about half of the students reported they only possessed an average competence in using CAT tools, and around half of the students stated their competence in using translation memories and terminologies was average (see Table 10). A majority of students also reported insufficient training in application of technology in completing translation tasks (see Table 9). For them, CAT tools were not frequently used in other translation courses or in their everyday translation work or practices. Tina made a typical comment:

I have been doing some freelance translations in my leisure time, but I did not use CAT tools very often. The main reason is that my translation projects are usually quite small and I feel using CAT tools will even complicate the translation process.

Students’ feeling of needing more practices with CAT tools was echoed in the study of Malenova (2019), which found that undergraduate students in translation technology courses would like to have more practices with CAT tools. Trainers can encourage students to use CAT tools as much as possible in their translation work and courses other than translation technology courses (Pym 2013). Although students felt that the use of CAT tools in their small translation projects would make things even complicated, we assume that this impression was mainly due to their unfamiliarity with the tools and insufficient deliberate practices on how to make use of the tools in different translation tasks, being small or large. Another possible solution is the use of flipped learning in translation technology training. The details will be discussed in the implications of the findings in the “Implications” section.

It is encouraging to note that students mentioned the importance of selection ability in translation technology training (see Steven’s comment in the “Learning” section). Indeed, we have to bear in mind that the core skill of using CAT tools is “to quickly and accurately evaluate and select the most appropriate proposals from among the options presented” (Bowker and McBride 2017, p. 263). The importance of training critical selection ability in translation technology training has also been discussed by others such as Austermuehl (2013), Pym (2013) and Ginovart Cid et al. (2020). For instance, the ability to decide on a machine translation segment was listed as the second most important skills for professional post-editors in the views of language service companies (Ginovart Cid et al. 2020).

While it is important for trainers to go beyond the knowledge of CAT tools and put more emphasis on the practical use of translation technology as well as the training of critical selection capacity, the reality is that not all translation and interpreting graduates worked as full-time translators or interpreters. For instance, our findings show that almost half of the respondents said they would not be translators or interpreters (see section “Reaction”). There are therefore calls for more training on transferable skills in translation technology courses (O’Brien and Rossetti 2020; Heinisch 2019; Austermuehl 2013; Guerberof-Arenas and Moorkens 2019). Transferable skills in translation technology training are skills for both translational and non-translational activities (see Austermuehl 2013), such as speed-related skills, searching skills, skills of text editing and desktop publishing and collaboration skills, but these transferable skills were only mentioned by a small number of students as their perceived areas of growth after the translation technology training (see Table 8).

Quite a few students reported inadequate and poor competence in computer programming and translation management. One reason could be that computer programming was not a major teaching content in translation technology training. Another reason could be that students did not receive tangible benefits from the training. Daniel elaborated on this point:

I learnt some knowledge of computer programming but it had little to do with translation and interpreting practices. I still did not know how Python could help with my translation work.

There is a general impression that at present, the textbooks on Python for translation technology training are not particularly relevant for actual translation and interpreting tasks. The majority of translation and interpreting graduates are without prior computer programming experience, so it will be unrealistic to train them to be an expert in computer programming within 2 or 3 years of study. To optimize our students’ translation technology training, it is essential to incorporate the utilization of Python programming for creating programs that can automate and streamline their real-life translation tasks. By leveraging Python, students can write custom programs that enhance the automation and efficiency of their translation processes. This inclusion of Python programming will empower students by equipping them with the necessary skills to automate and improve the efficiency of their real-life translation tasks. These programs are not necessarily complicated. But the key is that teachers of computer programming in translation technology training should prioritize the needs of translators and interpreters. One example was found in Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, where a series of international workshops on translation technology were held to support translators and language learners to automate their preparation processes through Python programming. Trainers can also learn from research findings such as those of Mendoza Rivera et al. (2018) on the application of Python to translation related tasks and bring about changes in the teaching content of computer programming for translation and language majors.

Apart from computer programming, students had relatively low ratings for their competences of managing translation and localization projects. This result was not surprising, because such competences usually required the advanced use of technological tools (Jiménez-Crespo 2013), and the students in our sample were not overwhelmingly satisfied with their competence of using translation technology. Besides, the skills required for translation and localization project management “go beyond those required of a translator who mainly works in a computer-aided translation environment” (O’Brien and Rossetti 2020, p. 96). For example, one important additional skill required for managing translation projects is the ability to work in a team environment. Previous studies showed that some students did not consider their ability to work in project teams had improved after the completion of a CAT course (Rodríguez-Castro 2018). Similarly, only 3.4% of the students listed collaboration skills as the area of growth after training in the present study (see Table 8).

The content of translation and localization project management could be difficult for language majors to understand due to its strong technological components and conceptual complexity, unless real-life contexts of translation and localization project management are created for students. However, as were listed as two major difficulties perceived by the students, teachers did not provide sufficient real-world translation cases for training, and few experts from language service providers were invited to guide the students to implement the theoretical concepts to actual projects. Indeed, it was “a daunting task” (Zouncourides-Lull 2011, p. 72) to apply the theories and principles of project management to translation and localization projects.

Implications

Two implications can be drawn to enhance the effectiveness of translation technology training in the MTI programs in China, with possible applicability to some other contexts as well. Firstly, translation technology training should go beyond the knowledge of translation technology. Rather, it should put more emphasis on the practical use of translation technology. The majority of the class time was often used by teachers for explaining the steps of using translation technology tools or software, and students did not have enough time to practice the tools themselves or solve specific problems that they encountered in class. So, to overcome this problem, trainers can perhaps use flipped learning to encourage students to study the videos concerning the operational procedures of the tools prior to class. In this way, in-class time can be freed up for more interactive problem-solving activities with trainers and peers. These problem-solving activities include troubleshooting and the applications of translation technology to solve specific translation problems. The pre-class learning resources such as the video materials can also add to the teaching materials provided by translation technology textbooks. However, the implementation of flipped learning is challenging. For example, students need to be motivated enough to study the videos in advance. Trainers have to put in extra time and effort to make videos. At present, only Toto (2021) systematically studied the application of flipped learning in translation technology training. Toto (2021) found that flipped learning can improve the effectiveness of translation technology training, especially enabling students to have more time to independently practice translation tools. Further studies are needed to explore the feasibility of flipped learning to improve the effectiveness of translation technology training.

Secondly, trainers are encouraged to incorporate real-world translation projects and authentic experiential learning into the teaching of translation technology. Working on real-world translation projects is believed to enhance students’ competence of managing translation and localization projects, and equip them with translation skills and transferrable skills. These transferrable skills include searching, collaboration, communication and management skills, which translation and interpreting majors need to hone in order to prepare for jobs other than translators and interpreters (Hao and Pym 2023). Real-life translation and real-world translation projects in translation technology training enable students to use translation technology to make a difference in the real world and develop a meaningful engagement with the society outside the classroom (Uribe de Kellett 2022).

Conclusion

Teaching and learning effectiveness are at the crux of translation technology training. In order to effectively prepare our translation students for the era of technology, we investigated the effectiveness of translation technology training in the MTI programs in China, using the Kirkpatrick training evaluation model. The focus of the study is to find out what aspects of translation technology training are satisfactory, and what aspects need to be improved in future training programs. Although this study particularly addresses translation technology training in China, we believe our findings can be a useful reference to many parts of the world, and our discussions and suggestions may extend to translation technology training programs in other teaching and learning contexts.

One general conclusion is that knowledge of translation technology is easier to get across, but skills of translation technology application depend on abundant practices. Another conclusion is that students are more or less able to use computer-assisted translation tools and translation memories, but it seems that they have difficulties in synthesizing the knowledge and skills to complete tasks with extra demands such as translation and localization project management. In line with the implications and suggestions mentioned above, teachers should make every effort to encourage students to practice applying translation technology to real-world situations. It is also important to recognize that graduate-level translation students might have other priorities in their learning, as we can see from the results that 48.05% of the participants did not want to be translators or interpreters upon graduation. Fortunately, these students in our study reported that they could see the value and relevance of translation technology to their intended professions other than translators or interpreters. However, only a few students considered the transferable skills from working as translators to other professions as areas of growth after undergoing translation technology training (see Table 8). This indicates that teachers should identify and stress the transferable skills in translation technology training.

One limitation of our study is that the findings might not apply universally to all translation technology students. This is because we used nonprobabilistic sampling methods, such as convenience sampling and snowball sampling, to select participants for our survey. Although these techniques helped us gather data efficiently, they may introduce some bias and limit the generalizability of our study’s conclusions. Therefore, caution should be exercised when interpreting the results in terms of the broader population of translation technology students.

Methodologically, this study is one of the few attempts to use the Kirkpatrick model to study training effectiveness in translation and interpreting research. The Kirkpatrick model is a useful framework to clarify and evaluate the concept of effectiveness for the purpose of improving translation training programs. The operationalization of the model and list of questionnaire items can be used as a reference for investigating effective training in translation and interpreting studies. Future research can explore the effectiveness of translation technology training from teachers’ perspectives, i.e., the knowledge structure of translation technology teachers (cf. Li 2018).

Data availability

The data presented in the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Alcina A (2008) Translation technologies: scope, tools and resources. Target 20(1):79–102

Alcina A, Soler V, Granell J (2007) Translation technology skills acquisition. Perspectives 15(4):230–244

Alsalamah A, Callinan C (2021) The Kirkpatrick model for training evaluation: bibliometric analysis after 60 years (1959–2020). Ind Commer Train 54(1):36–63

Austermühl F (2013) Future (and not-so-future) trends in the teaching of translation technology. Revista Tradumàtica: tecnologies de la traducció 11:326–337

Bowker L (2015) Computer-aided translation: translator training. In: Sin-wai C (ed) Routledge encyclopedia of translation technology. Routledge, London and New York, p 88–104

Bowker L, McBride C (2017) Précis-writing as a form of speed training for translation students. The Interpreter and Translator Trainer 11(4):259–279

Bowker L (2023) De-mystifying translation: introducing translation to non-translators. Routledge, London and New York

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 3(2):77–101

Burgoyne J (2012) Evaluation of management, leadership, and organizational development. In: Seel NM (ed) Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning. Springer, New York, p 1174–1176

Carsten S, Ciobanu D, Mankauskiene D (2021) The challenge of evaluating open interpreter training resources: case study of ORCIT. Interpret Transl Train 15(4):490–505

Doherty S, Kenny D (2014) The design and evaluation of a statistical machine translation syllabus for translation students. Interpret Transl Train 8(2):295–315

Doherty S, Moorkens J (2013) Investigating the experience of translation technology labs: pedagogical implications. J Spec Transl 19:122–136

Dömyei Z (2007) Research methods in applied linguistics: quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methodologies. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Galletta A (2013) Mastering the semi-structured interview and beyond: from research design to analysis and publication. New York University Press, New York and London

Gaspari F, Almaghout H, Doherty S (2015) A survey of machine translation competences: insights for translation technology educators and practitioners. Perspectives 23(3):333–358

Ginovart Cid C, Colominas C, Oliver A (2020) Language industry views on the profile of the post-editor. Transl Spaces 9(2):283–313

Guerberof Arenas A, Moorkens J (2019) Machine translation and post-editing training as part of a master’s program. J Spec Transl 31:217–238

Guerberof-Arenas A, Toral A (2020) The impact of post-editing and machine translation on creativity and reading experience. Transl Spaces 9(2):255–282

Hao Y, Pym A (2023) Where do translation students go? A study of the employment and mobility of Master graduates. Interpret Transl Train 17(2):211–229

Heinisch B (2019) Accessibility as a component in inclusive and fit-for-market specialised translator training. InTRAlinea. https://www.intralinea.org/specials/article/2420

Jiménez-Crespo MA (2013) Translation and web localization. Routledge, London and New York

Kirkpatrick D, Kirkpatrick J (2006) Evaluating training programs: the four levels, 3rd edn. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, San Francisco

Kirkpatrick JD, Kirkpatrick WK (2016) Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation. Association for Talent Development, Virginia

Koponen M (2015) How to teach machine translation post-editing? Experiences from a post-editing course. In: O’Brien S, Simard M (eds) Proceedings of the 4th workshop on post-editing technology and practice. Association for Machine Translation in the Americas, Miami, p 2–15

Kornacki M (2018) Computer-assisted translation (CAT) tools in the translator training process. Peter Lang, Berlin

Li D (2013) Teaching business translation: a task-based approach. Interpret Transl Train 7(1):1–26

Li D (2018) Teaching of translation technology: curriculum, methods and teacher education. Paper presented at the Fourth International Conference on Research into the Didactics of Translation (didTRAD). Autonomous University of Barcelona, Barcelona, June 2018

Li D (2022) Translation creativity in the era of translation technology. Studi Estet 1:316–322

Li D, Zhang C, He Y (2015) Project-based learning in teaching translation: students’ perceptions. Interpret Transl Train 9(1):1–19

Mahasneh A (2013) Translation training in the Jordanian context: curriculum evaluation in translator education. Doctoral Thesis, State University of New York at Binghamton

Malenova E (2019) Cloud technologies in a translation classroom. trans-kom 12(1):76–89

Massey G, Kiraly D (2021) The Dreyfus model as a cornerstone of an emergentist approach to translator expertise development. In: Mangiante EMS, Peno K (eds) Teaching and learning for adult skill acquisition: applying the Dreyfus and Dreyfus model in different fields. Information Age Publishing, North Carolina, p 237–266

Mellinger CD (2017) Translators and machine translation: knowledge and skills gaps in translator pedagogy. Interpret Transl Train 11(4):280–293

Mellinger CD, Hanson TA (2020) Methodological considerations for survey research: validity, reliability, and quantitative analysis. Linguist Antverp New Ser Themes Transl Stud 19:172–190

Mendoza Rivera O, Mitkov R, Pastor GC (2018) A flexible framework for collocation retrieval and translation from parallel and comparable corpora. In: Mitkov R, Monti J, Pastor GC, Seretan V (eds) Multiword units in machine translation and translation technology. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, p 165–179

MEPRC and NLSCPRC (2018) China’s standards of English language ability. Higher Education Press, Beijing

Nunes Vieira L, Zhang X, Yu G (2021) ‘Click next’: on the merits of more student autonomy and less direct instruction in CAT teaching. Interpret Transl Train 15(4):411–429

O’Brien S, Rodríguez Vázquez S (2020) Translation and technology. In: Laviosa S, González-Davies M (eds) The Routledge handbook of translation and education. Routledge, London and New York, p 264–277

O’Brien S, Rossetti A (2020) Neural machine translation and the evolution of the localisation sector: implications for training. J Int Localization 7(1–2):95–121

Olvera Lobo MD, Robinson B, Castro Prieto RM, Quero Gervilla E, Muñoz Martín R, Muñoz Raya E, Díez Lerma JL (2007) A professional approach to translator training (PATT). Meta 52(3):517–528

Pacheco Aguilar R (2019) The question of authenticity in translator education from the perspective of educational philosophy. In: Kiraly D, Massey G (eds) Towards auothentic experiential learning in translator education. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, Newcastle upon Tyne, p 17–38

Pickering JD, Joynes VC (2016) A holistic model for evaluating the impact of individual technology-enhanced learning resources. Med Teach 38(12):1242–1247

Pietrzak P, Kornacki M (2021) Using CAT tools in freelance translation: insights from a case study. Routledge, London and New York

Pym A (2013) Translation skill-sets in a machine-translation age. Meta 58(3):487–503

Pym A, Torres-Simón E (2021) Is automation changing the translation profession? Int J Sociol Lang 2021(270):39–57

Rodríguez-Castro M (2018) An integrated curricular design for computer-assisted translation tools: developing technical expertise. Interpret Transl Train 12(4):355–374

Rodríguez-Inés P (2010) Electronic corpora and other information and communication technology tools: an integrated approach to translation teaching. Interpret Transl Train 4(2):251–282

Samman HM (2022) Evaluating machine translation post-editing training in undergraduate translation programs—an exploratory study in Saudi Arabia. Doctoral Thesis, University of Southampton

Sánchez-Castany R (2023) Teaching translation technologies: an analysis of a corpus of syllabi for translation and interpreting undergraduate degrees in Spain. In: Massey G, Huertas-Barros E, Katan D (eds) The human translator in the 2020s. Routledge, London and New York, p 27–43

Stufflebeam DL (1971) The relevance of the CIPP evaluation model for educational accountability. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Association of School Administrators, Atlantic City, N.J., 24 February 1971

Su W (2021) Integrating blended learning in computer-assisted translation course in light of the new liberal arts initiative. In: Jia W, Tang Y, Lee RST, Herzog M, Zhang H, Hao T, Wang T (eds) Emerging technologies for education. 6th international symposium, SETE 2021, Zhuhai, China, November 11–12, 2021. Springer, Cham, p 415–424

Su W, Li D, Zhao X, Li R (2021) Exploring the effectiveness of fully online translation learning during COVID-19. In: Pang C, Gao Y, Chen G, Popescu E, Chen L, Hao T, Zhang B, Baldiris SM, Li Q (eds) Learning technologies and systems: 19th international conference on web-based learning, ICWL 2020, and 5th international symposium on emerging technologies for education, SETE 2020, Ningbo, China, October 22–24, 2020. Springer, Cham, p 344–356

Sycz-Opoń J, Gałuskina K (2016) MT evaluation protocol as an educational tool for teaching machine translation: experimental classes. J Transl Educ Transl Stud 1(1):35–49

Szarkowska A (2019) A project-based approach to subtitler training. Linguist Antverp New Ser Themes Transl Stud 18:182–196

Toto P (2021) Flipped classrooms and translation technology teaching: a case study. In: Wang C, Zheng B (eds) Empirical studies of translation and interpreting: the post-structuralist approach. Routledge, London and New York, p 240–258

Uribe de Kellett A (2022) Real-world translation: learning through engagement. In: Hampton C, Salin S (eds) Innovative language teaching and learning at university: facilitating transition from and to higher education. Research-publishing.net, Voillans, p 133–142

Wang H (2019) The evolution of the global language service market. In: Yue F, Tao Y, Wang H, Cui Q, Xu B (eds) Restructuring translation education: implications from China for the rest of the world. Springer, Singapore, p 3–12

Wang H, Li D, Li L (2018) Translation technology teaching in MTI programs in China: problems and suggestions. Technol Enhanc Foreign Lang Educ 181(03):76–82+94

Zouncourides-Lull A (2011) Applying PMI methodology to translation and localization projects. In: Dunne KJ, Dunne ES (eds) Translation and localization project management: the art of the possible. John Benjamins, Amsterdam and Philadelphia, p 71–93

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Center for Translation Studies of Guangdong University of Foreign Studies (Fund No. CTSHQ202201), Guangdong Planning Office of Philosophy and Social Sciences (grant number GD23WZXC01-10) [广东省哲学社会科学规划2023年度外语学科专项一般项目“译员和机器同声传译的对比与协作研究”, 项目编号: GD23WZXC01-10], and 2022年度校级教学质量与教学改革工程立项建设项目“面向新文科的计算机辅助翻译课程改革与研究”,广外教【2022】50号.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the work: WS. Supervision: DL. Original draft: WS. Revising and editing: DL. Data analysis and interpretation: WS and DL.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Approval was obtained from University of Macau Ethics Review Committee. The procedures used in this study adhere to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, W., Li, D. The effectiveness of translation technology training: a mixed methods study. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10, 595 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02066-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02066-2