Abstract

The huge health expenditure for chronic diseases in the elderly is one of the uncertain factors that may cause the Borderline poor families to return to poverty after China fully lifts itself out of poverty in 2020, especially in rural low-income areas. Based on the latest data released by China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study, this paper used the two-part model to analyze the impact of elderly chronic diseases on health expenditure and catastrophic health expenditure of Borderline poor families in rural China. Some interesting results were found. For example, elderly chronic diseases such as stroke and hepatic disease have a large impact on the catastrophic health expenditures of families on the edge of poverty in rural China. Therefore, the government should drive middle-aged and elderly people to actively participate in physical exercise and prevent the high incidence of chronic diseases in the elderly. Furthermore, the government should improve the medical insurance system to provide solid support for low-income families and other vulnerable groups to avoid returning to poverty.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Health and healthcare expenditures closely related to population aging have become an issue of concern to scholars around the world (Xu et al., 2022a). According to the Seventh National Census in China (2021), the proportion of people aged 65 and above in the total population rose from 10.5% in 2015 to 13.5% in 2020, which poses a serious challenge to both the government and families’ health expenditure burden. The per capita health expenditure for outpatients and inpatients, respectively, increased from 233.9 yuan(RMB) and 8268.1 yuan(RMB) to 324.4 yuan(RMB) and 10619.2 yuan (RMB) from 2015 to 2020 (China Health Statistical Yearbook, 2021). At the same time, chronic diseases in the elderly impact the health expenditure of residents and may lead to the occurrence of poverty due to illness. According to China Health Statistics Yearbook in 2021 (Fig. 1), the prevalence of chronic diseases in China’s population aged 65 and over was 467.8% in 2008, but it increased to 623.3% in 2018. It also shows that 44.1% of poor registered households had fallen into poverty due to serious chronic diseases by the end of 2018. As serious chronic diseases require long-term treatment, the resulting health expenditure exceeds the household disposable income, which has been an important reason for the Borderline poor families’ return to poverty. According to the WHO definition, when an individual’s medical expenditure exceeds 40% of the family’s ability to pay, it means that the individual has incurred Catastrophic health expenditure, which reflects the likelihood that a family will return to poverty because of illness (Gao et al., 2019). Catastrophic health expenditure is more likely to occur due to low household income in rural China.

Studies by academics around the world have shown that chronic disease increases health expenditure, even if the individual has health insurance. In China, using the data of the China Health and Nutrition Survey (CHNS), Xie (2011) found that chronic diseases significantly increase medical expenses, and wealthy individuals are significantly more advantageous than poor patients in resisting the impact of chronic diseases. Liu et al. (2020) showed that out-patient medical expenditure, inpatient medical expenditure, and total medical expenditure of the elderly with chronic diseases increased by 20.1%, 11.5%, and 13% compared with those without chronic diseases, respectively. Using the two-stage least squares model (2SLS), Zhang and Li (2021) empirically tested the impact of medical insurance on the medical status of elderly chronic diseases and found that medical insurance significantly increased the outpatient and inpatient medical costs of elderly chronic diseases. This conclusion is further supported by research from scholars outside China. After analyzing the trend of out-of-pocket medical expenditures for chronic diseases in the United States from 1996 to 2005, Paez et al. (2009) found that per capita out-of-pocket medical expenses increased by 39.4% due to chronic diseases. Meraya et al. (2015) found that total health care expenditures varied by chronic disease combination type among adults with arthritis, diabetes, cardiopathy, and hypertension. Using data from the Kagera Health and Development Survey, Counts and Skordis-Worrall (2016) constructed a 19-year panel dataset and found that households affected by chronic disease spend 22% more on health care than households not affected in Tanzania. All the studies confirm that Chronic diseases in the elderly have a heavy economic burden on families, especially in countries with large elderly populations such as India and China (Hsieh and Qin, 2018; Kothavale et al., 2021; Puri and Pati, 2022; Sun et al. 2020).

Catastrophic health expenditure is characterized by reflecting the poverty status of residents. In addition to analyzing the impact of chronic diseases on catastrophic health expenditure, scholars often study the resulting inequality and poverty. Wang and Li (2014) showed that the incidence and intensity of catastrophic health expenditure in elderly families with chronic disease were significantly affected by family-related factors and the medical treatment behavior of chronic disease patients, and the risk inequality of catastrophic health expenditure was also determined. Yu et al. (2019) established a triple differential measurement model and concluded that medical insurance significantly increases the risk of catastrophic health expenditure for patients with chronic diseases, and this effect is more obvious in the lower-income group. Studies from countries other than China have reached similar conclusions. Swe et al. (2018) used Bayesian regression models and found catastrophic health expenditure has increased over time due to a 4.6% increase in the inflation-adjusted costs of chronic diseases, including asthma, diabetes, cardiopathy, malaria, jaundice, and parasitic diseases during 1995–2010 in Nepal. Shumet et al. (2021) analyzed catastrophic health expenditure of 302 patients with chronic diseases in Northeast Ethiopia in 2018 and found that catastrophic health expenditure occurs in 64.2% of patients with chronic diseases, among which expensive medical services, transportation, and drugs are the reasons for catastrophic health expenditure. Kien et al. (2017) used principal component analysis (PCA) to explore the catastrophic health expenditures associated with NCDs (non-communicable diseases) and further found that these households are likely to be poorer in northern Vietnam. As it turns out, the health economic burden caused by chronic diseases in the elderly has a greater impact on poor families (Deaton, 2002; Somkotra and Lagrada, 2008; Kang and Kim, 2018; Rezaei et al., 2019; Shumet et al., 2021). Moreover, many scholars have put forward different policy suggestions (Jung and Lee, 2022; Pak, 2021). For example, some scholars believe that the fundamental source of health problems, such as environmental pollution, should be solved (Dimitris et al., 2020; Reza et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2022b). Other scholars advocate the government’s medical system reform (Kheibari et al., 2019; Karan et al., 2017; Zhou et al., 2022).

To sum up, some scholars around the world have studied the relationship between elderly chronic diseases and health expenditure, but there are few studies on catastrophic health expenditure. In particular, with the increasing economic burden of chronic diseases, there is little research on the economic pressure and the resulting risk of returning to poverty of rural elderly, which is a relatively vulnerable group. Therefore, this paper takes the rural elderly with chronic diseases and their families as the Borderline poor families to explore the huge economic pressure and the risk of returning to poverty caused by their catastrophic health expenditures. In addition, another innovation of this paper is to include seven of the most common and representative chronic diseases in the empirical analysis. While most existing studies discuss the relationship between chronic diseases and health expenditure by either integrating all chronic diseases or just one of them, this paper includes all seven of the most representative chronic diseases. Finally, the data adopted in this paper are the latest data released by China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS).

Methods

Model design

Health expenditure model

This paper first analyzed the impact of chronic disease on the health expenditure (HE) of middle-aged and elderly groups in rural China. Due to the existence of many zero values in health expenditure data, it does not meet the assumption that the random error term is subject to normal distribution. Therefore, the two-part model (Duan et al., 1983) is considered, which is divided into two independent parts. The model is as Formula 1:

Among them, f(yi|di = 1, xi) is health expenditure density function. The first phase indicates whether the patient incurs health expenses. di was used to describe this decision, and the logit model was used to estimate this probability in this study. The second part represents that patients produce health expenditure. In order to reduce the skewness distribution of health expenditure, the Log-linear model is usually used to explore the influencing factors of health expenditure. Probability of health expenditure as Formula 2:

The log of the second part of health expenditure can be expressed as Formula 3:

xi represents the independent variable and the control variable affecting the decision, and ε1i, ε2i represents the disturbance term in the equation.

Catastrophic health expenditure model

Catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) and the mean intensity of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE mean intensity) are measured by household out-of-pocket medical expenditures, consumption expenditures, and food expenditures (Formula 4 and 5). Among them, the CHE mean intensity reflects the impact of health expenditure on family living standards (Wang and Zhang, 2021).

where OOPEi refers to the out-of-pocket medical expenses of individual i; ctpi refers to the affordability of individual i. It is the difference between the total consumption expenditure and the expenditure for food purchases.

Variable selection

Dependent variables

Health expenditure (HE) and catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) is used to describe the economic pressure on Borderline poor families due to health problem in rural China. Health expenditure (HE) is measured by outpatient’s visit probability (OVP) and the logarithmic form of health expenditure (LHE). Out-of-pocket expenditures for outpatient and hospitalization expenditure are included. Catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) is measured by the occurrence probability and the mean intensity of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE mean intensity). Among them, outpatient’s visit probability (OVP) and the occurrence probability of catastrophic health expenditure are dichotomous variables, while the logarithmic form of health expenditure (LHE) and the mean intensity of catastrophic health expenditure (CHE mean intensity) are continuous variables.

Independent variables

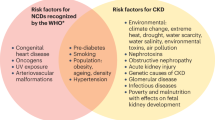

To explore the effects of elderly chronic diseases (ECD) on the catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) of Borderline poor families in rural China, this paper selected the prevalence of seven chronic diseases, income status(or poverty status), and self-rated health status as core independent variables. The ECD types are referred to the studies of other scholars (Kim and Richardson, 2014), and the most common or expensive ECD are selected as representatives, which include hypertension, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung disease, hepatic disease, cardiopathy, and stroke (as shown in Fig. 2). Income status is divided into five levels, namely, Poverty, Close to the poverty, Low income above the poverty line, Middle-income, and High income. It is based on the poverty line (2995 yuan), 10% above and 10% below the poverty line (2695.5 yuan; 3294.5 yuan) in 2018.

Control variables

This paper selected demographic characteristics such as gender, age, marital status, and socioeconomic characteristics such as education, medical insurance, and endowment insurance as control variables (as shown in Table 1).

Data source

The data used in this paper is from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which is publicly available and organized by the China Center for Social Sciences Investigation, Peking University. The database was conducted among people aged 45 and above in a random sample of households and covered their social-economic data and high-quality physical/mental health status data. In this paper, the latest published samples with complete data from CHARLS database in 2018 were selected as the research object, and the samples of middle-aged and elderly people over 45 years old in rural China were screened. Finally, 6872 samples were obtained after removing missing values.

Results

Statistical description of variables

Table 2 is the descriptive statistics of the sample in rural China. The outpatient’s visit probability (OVP) was 28.6% on average, and the catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) incidence was 28.3%. High blood pressure, cardiopathy, and stroke account for the largest number of chronic diseases. The average level of education is below secondary education, indicating that rural areas are generally not well educated. In addition, the majority of the samples were married, with an average age of 62. More women than men had medical insurance and endowment insurance.

Elderly chronic diseases and health expenditure in Rural China

The regression results of the relationship between elderly chronic diseases and health expenditure in rural areas was shown in Table 3.

OVP (Outpatient’s visit probability)

First, the Outpatient’s visit probability will increase with the increase in income. Among them, the patients with 10% poverty level had the highest probability of receiving medical treatment, which was about 1.5 times higher than that of the poorest group (OR = 1.478). Second, except for hypertension and diabetes, other chronic diseases had a significant influence on the probability of medical visit (p < 0.01). Third, the group with poor self-rated health status passed the test at the significance level of p < 0.01, and the Outpatient’s visit probability in the group with poor health was about 2.8 times higher than that in the group with the best health status (OR = 2.769).

LHE (Logarithmic form of health expenditure)

First, there are differences in the influencing mechanisms that influence the Outpatient’s visit probability and generate health expenditure, which is more obviously on endowment insurance. Compared with the population without endowment insurance, people having endowment insurance significantly increases their health expenditure. Second, compared with other income groups, the health expenditure of low-income groups still increased significantly (p < 0.05). In addition, with the increase in income level, health expenditure shows a negative growth trend. Thirdly, all the seven chronic diseases increased the level of health expenditure to varying degrees, and the results were very significant, among which cancer had the highest impact on health expenditure.

Elderly chronic diseases and catastrophic health expenditure in Rural China

The regression result of the relationship between elderly chronic diseases and catastrophic health expenditure in rural areas was shown in Table 4.

CHE (Catastrophic health expenditure)

First, different income has different influences on catastrophic health expenditure. The catastrophic health expenditure generation of the low- and middle-income groups is higher, which is 1.5 (OR = 1.472) and 1.03 (OR = 1.030) times of the poorest group, respectively. Second, seven chronic diseases significantly affected the catastrophic health expenditure level (p < 0.01). Catastrophic health expenditure was significantly higher in patients with chronic disease than in those without chronic disease. Thirdly, the catastrophic health expenditure probability increased significantly by 3% (OR = 3.004) for each higher grade of self-rated health status score. In addition, catastrophic health expenditures were 1.5 times higher in households with a spouse than in single households (OR = 1.505).

CHE mean intensity

First, there are significant differences between CHE mean intensity and catastrophic health expenditure level. CHE mean intensity was significantly affected only by chronic lung disease and stroke. Compared with other chronic diseases, these two chronic diseases have a more profound impact on residents’ living standards. Second, the CHE mean intensity of the low- and high-income groups increased with the income level, indicating that the current income cannot cope with catastrophic health expenditure well and the risk resistance is weak. The CHE mean intensity of the high-income group decreased significantly (p < 0.01), and decreased by 49.5% for every 1 unit of income increase. Third, except for basic medical insurance, other types of medical insurance and endowment insurance reduced CHE mean intensity level.

Robustness test

To test the regression results in Tables 3 and 4, the robustness test was carried out (Tables 5–7). First of all, replace chronic diseases type in the health expenditure model: hypertension, diabetes, and cancer were replaced by blood lipid, kidney, and stomach. Then, change the catastrophic health expenditure threshold in the catastrophic health expenditure model. Among them, the catastrophic health expenditure threshold is selected according to previous studies by scholars and replaced with two dimensions of 30% and 35% (Gao et al., 2019). Finally, the sample age range was narrowed from 45 years old to 60 years.

Replace the type of elderly chronic disease

The influence of chronic diseases on the Outpatient’s visit probability and health expenditure does not change with the change of chronic diseases. In Table 3, hypertension and diabetes have a higher probability of Outpatient’s visit than those suffering from other chronic diseases. In Table 5, after replacing chronic diseases, all seven chronic diseases significantly affected the probability of Outpatient’s visit. In addition to stroke and hepatic disease, kidney disease is another chronic disease that affects medical treatment. People with kidney disease were 2.5 times more likely to visit a doctor than people without chronic disease (OR = 2.481). In addition, people’s financial situation close to poverty and low income still significantly influences the level of health expenditure. A positive regression coefficient indicates that low-income groups face higher health costs than the poorest group. Furthermore, the effects of self-rated health, endowment insurance, and age on health expenditure are consistent with the conclusion in Table 3.

Change the threshold of catastrophic health expenditure

The influence of chronic diseases on catastrophic health expenditure and CHE mean intensity has nothing to do with the CHE threshold. First of all, Table 6 is consistent with the conclusions in Table 4. All seven chronic diseases still passed the significance test at 30% and 35% thresholds, proving that chronic diseases increase patients’ risk of catastrophic health expenditure. Among the seven chronic diseases, stroke, hepatic disease, and cancer are still high-risk chronic diseases that lead to catastrophic health expenditure and have nothing to do with threshold, and the seven diseases will increase the impact of increased health expenditure on the family living standard to varying degrees, among which cancer still has the greatest impact. The impact of residents’ self-rated health, age, and marital status on catastrophic health expenditure is consistent with the conclusion in Table 4, which significantly affects catastrophic health expenditure and CHE mean intensity and has nothing to do with the threshold value.

Narrow down the sample age range

Unlike the previous samples were all over 45 years old, the following robustness tests were performed for samples of only those over 60 years old (Table 7).

In the catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) test after narrowing down the sample age range, five of the seven chronic diseases passed the significance test, all of which significantly increased the risk of CHE, and stroke remained the chronic disease with the highest risk of CHE (OR = 2.199). Besides education level, individual characteristics also passed the significance test. As can be seen from the regression results of CHE mean intensity in Table 7, the elderly over 60 years old suffer from different types of chronic diseases and have different influences on CHE mean intensity. In addition, the income status of high-income people can reduce the incidence of CHE and the CHE mean intensity decreases by 88.6% with each increase in income level.

Discussion

Main conclusions

Elderly chronic diseases are the important cause of catastrophic health expenditure in rural China

The regression results showed that most chronic diseases had a significant positive impact on health expenditure and catastrophic health expenditure incidence. Patients with chronic diseases need long-term medication and hospitalization to cope with the impact of diseases on their bodies, which leads to increased out-of-pocket expenditures, consistent with the conclusions of previous scholars (Xie, 2011). The chronic diseases that contributed most to increasing health expenditure were cancer, stroke, and hepatic disease. Moreover, some scholars have proposed that individuals with catastrophic health expenditure are consistent with those in poverty (Feng and Li, 2009; Ding and You, 2019), and catastrophic health expenditure has a “pro-poverty” effect (Liu and Zhang, 2020). Therefore, catastrophic health expenditure reflects the corresponding poverty or income status of individuals and families (Wang and Zhang, 2021). The three chronic diseases that have the greatest impact on poverty continue to be a stroke, cancer, and hepatic disease. Some scholars have found that cancer patients have the highest risk of fatal stroke (Zaorsky et al., 2019). For patients with chronic diseases, they may suffer from not just one chronic disease, but multiple chronic diseases and the interaction of chronic diseases will cause higher harm to the body and higher health expenditure. As a result, patients with chronic diseases fell into poverty under the background of “income reduction” and “expenditure increase”.

The Borderline poor families in rural China are more affected by elderly chronic diseases than other income groups

Regression results show that poor people have a low Outpatient’s visit probability, resulting in less health expenditure. Considering their own economic situation, poor people are likely to choose not to seek medical treatment even if they get sick, and there will be no health expenditure. The Borderline Poor Families above the poverty line have the highest rate of medical treatment, resulting in significantly the highest health expenditure. In the regression results for catastrophic health expenditure incidence, the low-income groups passed the significance test. Lower-income groups were 1.48 times more likely to see a doctor (OR = 1.478) and 1.47 times more likely to have catastrophic health expenditure than the poorest group (OR = 1.472). Overall, with the increase in income, health expenditure decreases, and the probability of catastrophic health expenditure also decreases, confirming other scholars’ conclusions (Wang and Li, 2014; Behera and Dash, 2020). Although the income of low-income people is higher than that of poor people, catastrophic health expenditure poverty is not degraded, and the CHE mean intensity is higher, indicating that chronic diseases have the deepest and most extensive impact on low-income people in the sample population, and the probability of returning to poverty due to disease is also higher.

Policy implications

Drive middle-aged and elderly people to actively participate in physical exercise and prevent the high incidence of chronic diseases in the elderly

Prevention at the source is a low-cost and effective way to mitigate the impact of chronic diseases on health expenditures and the return to poverty caused by chronic diseases. Therefore, the government should try to encourage residents to take an active part in physical exercise, especially middle-aged and elderly people. First of all, relevant departments can increase the investment and construction of sports facilities around residents’ gathering places, so as to provide more places and possibilities for the whole people to participate in physical exercise. Second, the prevention and publicity of chronic diseases should be strengthened, and middle-aged and elderly people should be encouraged to regularly test their physical indicators every year, screen for common chronic diseases, and seek medical treatment in time if they feel unwell.

Perfect the medical insurance system to provide a solid support for low-income families and avoid returning to poverty

Medical insurance can reduce the total medical expenses of middle-aged and old people and reduce the economic pressure on middle-aged and old families. In particular, the marginal utility of medical insurance for rural elderly and low-income groups is higher. From the perspective of the fairness and efficiency of the promotion system, medical insurance by expanding the scope of the low-income groups to ensure, to reduce the pay scale measures such as strengthening the protection of vulnerable join groups for the rural elderly people and low-income groups more welfare policy, for the rural elderly people and low-income earners to provide more protection.

Improve the economic income of low-income rural families by promoting the rural industries’ development

Improving economic income is fundamental to preventing low-income families from returning to poverty. Therefore, the government should actively promote rural revitalization and promote the development of rural industries to guarantee the economic foundation of rural low-income families. First of all, the government should formulate talent policies to attract young and middle-aged outstanding and local talents back to rural China, to make up for the current unreasonable talent structure dominated by the elderly. Second, the government should actively guide rural industries to develop in a high-quality and green direction and promote their long-term sustainable development. Finally, it is necessary to strengthen innovation, break traditional ideas and take the initiative to learn from the development cases of other regions, to realize the prosperity of rural families.

Data availability

Please refer to: http://charls.pku.edu.cn/index.html. More data that if the reader has a personal request, we will provide it to him.

References

Behera DK, Dash U (2020) Is health expenditure effective for achieving healthcare goals? Empirical evidence from South-East Asia Region. Asia-Pac J Reg Sci 4:593–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41685-020-00158-4

Counts CJ, Skordis-Worrall J (2016) Recognizing the importance of chronic disease in driving healthcare expenditure in Tanzania: analysis of panel data from 1991 to 2010. Health Policy Plan 31(4):434–443. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czv081

Deaton A (2002) Policy implications of the gradient of health and wealth. Health Aff 21:13–30. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.13

Dimitris E, Perez-Velasco R, Walton H, Gumy S, Williams M, Kelly FJ, Künzli N (2020) The role of burden of disease assessment in tracking progress towards achieving WHO global air quality guidelines. Int J Public Health 65:1455–1465. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-020-01479-z

Ding J, You L (2019) Study on the impact of basic medical insurance on catastrophic health expenditure of the elderly. Insur Res 12:98–107. (In Chinese)

Duan N, Manning WG, Morris CN, Joseph P (1983) A comparison of alternative models for the demand for medical care. J Bus Econ Stat 1(2):115–126. https://doi.org/10.2307/1391852

Feng J, Li Z (2009) Study on the compensation model of China’s rural medical security system. Econ Res 44(4):103–115. (In Chinese)

Gao J, Li H, Xu Y (2019) Can commercial medical insurance alleviate “poverty caused by disease” in urban and rural residents insured families? J Jiangxi Univ Financ Econ5:81–91. [In Chinese]

Hsieh C-R, Qin X (2018) Depression hurts, depression costs: the medical spending attributable to depression and depressive symptoms in China. Health Econ 27:525–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/hec.3604

Jung H, Lee KS (2022) What policy approaches were effective in reducing catastrophic health expenditure? A systematic review of studies from multiple countries. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 20:525–541. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258-022-00727-y

Kang J-H, Kim C-W (2018) Relationship between catastrophic health expenditures and Income quintile decline. Osong Public Health Res Perspect 9(2):73–80. https://doi.org/10.24171/j.phrp.2018.9.2.06

Karan A, Yip W, Mahal A (2017) Extending health insurance to the poor in India: an impact evaluation of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana on out of pocket spending for healthcare. Soc Sci Med 181:83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.053

Kheibari MJ, Esmaeili R, Kazemian M (2019) Impacts of health reform plan in Iran on health payments distributions and catastrophic expenditure. Iran J Public Health 48(10):1861–1869

Kien VD, Minh HV, Ngoc NB, Phuong TB, Ngan TT, Quam MB (2017) Inequalities in household catastrophic health expenditure and impoverishment associated with noncommunicable diseases in Chi Linh, Hai Duong, Vietnam. Asia Pacif J Public Health 29:35S–44S. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539517712919

Kim J, Richardson V (2014) The impact of poverty, chronic illnesses, and health insurance status on out-of-pocket health care expenditures in later life. Soc Work Health Care 53(10):932–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2014.955940

Kothavale A, Puri P, Yadav S (2021) The burden of hypertension and unmet need for hypertension care among men aged 15–54 years: a population-based cross-sectional study in India. J Biosoc Sci 3:1–22. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0021932021000481

Liu E, Zhang Q, Feng Y (2020) Elderly poverty risk of chronic diseases: theoretical mechanism and empirical test. Insur Res 11:63–78. (In Chinese)

Liu S, Zhang Q (2020) Measurement and influencing factors of Catastrophic health expenditure of middle-aged and elderly families—an Empirical Study Based on Charls data. Popul South 35(02):67–80. (In Chinese)

Meraya AM, Raval AD, Sambamoorthi U (2015) Chronic condition combinations and health care expenditures and out-of-pocket spending burden among adults, medical expenditure panel survey, 2009 and 2011. Prev Chronic Dis 12:140388. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.140388

Paez KA, Zhao L, Hwang W (2009) Rising out-of-pocket spending for chronic conditions: a ten-year trend. Health Aff 28(1):15–25. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.15

Pak T-Y (2021) What are the effects of expanding social pension on health? Evidence from the basic pension in South Korea. J Econ Ageing 18:100287–3794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeoa.2020.100287

Puri P, Pati S (2022) Exploring the linkages between non-communicable disease multimorbidity, health care utilization and expenditure among aboriginal older adult population in India. Int J Public Health 67:1604333. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604333

Rezaei S et al. (2019) Socioeconomic inequality in catastrophic healthcare expenditures in Western Iran: A decomposition analysis Int J Soc Econ 46(9):1049–1060

Reza B, Ashrafi K, Motlagh MS, Hassanvand MS, Daroudi R, Fink G, Künzli N (2019) Health impact and related cost of ambient air pollution in Tehran. Environ Res 176:108547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2019.108547

Shumet Y, Mohammed SA, Kahissay MH, Demeke B (2021) Catastrophic health expenditure among chronic patients attending Dessie Referral Hospital, Northeast Ethiopia. Clin Econ Outcomes Res 13:99–107. https://doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S291463

Somkotra T, Lagrada LP (2008) Payments for health care and its effect on catastrophe and impoverishment: experience from the transition to Universal Coverage in Thailand. Soc Sci Med 67(12):2027–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.047

Swe KT, Rahman MM, Rahman MS, Saito E, Abe SK, Gilmour S, Shibuya K (2018) Cost and economic burden of illness over 15 years in Nepal: a comparative analysis. PLoS ONE 13(4):e0194564. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194564

Sun X, Zhou M, Huang L, Nuse B (2020) Depressive costs: medical expenditures on depression and depressive symptoms among rural elderly in China. Public Health 181:141–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.12.011.9

Wang Y, Zhang C (2021) Study on risk and influencing factors of catastrophic health expenditure of rural poor families—based on Charls data in 2018. China Health Policy Res14(01):44–49. (In Chinese)

Wang Z, Li X (2014) Analysis on influencing factors and inequality of catastrophic health expenditure of elderly chronic disease families. Popul Dev 20(03):87–95. (In Chinese)

Xie H (2011) The economic impact of chronic disease among Chinese residents. World Econ Rev 3(74):86. (In Chinese)

Xu X, Wang Q, Li C (2022a) The impact of dependency burden on urban household health expenditure and its regional heterogeneity in China: based on quantile regression method. Front. Public Health 10:876088. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.876088

Xu X, Yang H, Li C(2022b) Theoretical model and actual characteristics of air pollution affecting health cost: a review Int J Environ Res Public Health 19(6):3532. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19063532

Yu X, Shen Y, Xiong X (2019) Research on poverty caused by chronic diseases and multi-level medical security. Insur Res 12:81–97. (In Chinese)

Zaorsky NG, Zhang Y, Tchelebi LT, Mackley HB, Chinchilli VM, Zacharia BE (2019) Stroke among cancer patients. Nat Commun 10(1):5172. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13120-6

Zhang R, Li F (2021) Does medical insurance improve the medical status of chronic diseases of the elderly—empirical analysis based on Charls data. Sci Decision Mak 9:102–113. (In Chinese)

Zhou M, Sun X, Huang L (2022) Does social pension expansion relieve depression and decrease medical costs? Evidence from the rural elderly in China. Int J Public Health 67:1604296. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2022.1604296

Acknowledgements

Thanks to The National School of Development and The Chinese Center for Social Science Surveys at Peking University for providing CHARLS data. This paper is a phased achievement of The National Social Science Fund of China: Research on the blocking mechanism of the Borderline poor families returning to poverty due to illness, No. 20BJY057.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, XX; methodology, HY; software, HY; formal analysis, XX; resources, XX; data curation, HY; writing—review and editing, XX; project administration, XX.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

The data of this study came from China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS), which Peking University sponsored. It was ethical reviewed by Biomedical Ethics Committee, Peking University, Ethics Review and Approval No. IRB00001052-11015. We also obtain the confirmation of the need for ethical applications was waived by CHARLS Research Group, since CHARLS is an open and accessible (publicly-available) database, and the authors only used the data for academic research.

Informed consent

Not applicable. We obtain the confirmation of the need for ethical applications was waived by CHARLS Research Group, since CHARLS is an open and accessible (publicly-available) database, and the authors only used the data for academic research.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, X., Yang, H. Elderly chronic diseases and catastrophic health expenditure: an important cause of Borderline Poor Families’ return to poverty in rural China. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 9, 291 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01310-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-022-01310-5