Abstract

The present study aims to understand the experiences, challenges, psychological well-being and needs of clinical and non-clinical government healthcare workers (HCWs) during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Hyderabad-Karnataka (H-K) region. This qualitative study used purposive sampling method to recruit 221 HCWs working in the H-K region government hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Semi-structured interviews were carried out with those HCWs who agreed to participate. The data analyzed using conventional content analysis revealed three main themes: (1) experiences and challenges faced by HCWs; (2) psychological well-being and coping strategies used by HCWs; and (3) experience of and need for social support. The main findings of the current study are as follows: The HCWs experienced fear and apprehension during the early stages of the pandemic, but gradually, their fears reduced, and they perceived the situation to be the “new normal”. They experienced work-related (scarcity of resources, problems with PPE, communication issues, violence, and stigma) and family-related (fear of infecting family members, choosing work over family, inability to undertake family roles) challenges while serving during the pandemic. They reported increased psychological issues (psychological distress, experience of loss, and feelings of guilt and helplessness). Conversely, they reported a need for emotional stability. The HCWs reported using adaptive (emotion-focused, problem-focused, and religious) and maladaptive (avoidance and substance abuse) coping strategies to cope with these challenges and psychological problems. They also sought social support (from family, friends, colleagues, and superiors) and raised the need for organizational, personal, and societal support to cope with the pandemic. The HCWs experienced physical and psychological burnout, especially from stretching beyond the assigned roles due to a shortage of resources and workforce. However, amidst juggling with work and family responsibilities, HCWs were found to be emotionally stable and reported to have a positive outlook in general. Besides, emphasizing the regulation of policies for meeting their primary needs, they stressed the need for professional psychological services with need-based intervention strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

COVID-19 is caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) (WHO, 2020a). Globally, 35,274,993 cases and 1,038,534 deaths were reported by the end of October 2020 (WHO, 2020b).The contagious nature of the virus and a lack of knowledge in treating the disease and dealing with the pandemic placed tremendous pressure on healthcare systems worldwide. It was especially true for frontline HCWs (Nagesh & Chakraborty, 2020), who were among the most vulnerable and high-risk groups (International Council of Nurses, 2020; The Lancet, 2020).

Being one of the most populous countries globally, India has a healthcare system still impeded by social and economic barriers (Younger, 2016). According to 2015 National Health Policy draft, the healthcare system in India is constrained by a combination of factors such as dysfunctional infrastructure, poor health financing, and lack of adequate human workforce. Overall, India’s health care system is weaker and more impoverished than developed countries. The expenditure for healthcare facilities in government hospitals is deficient. It exerts more work stress on HCWs in such hospitals than their counterparts in the developed countries in the West (Reddy et al., 2011). This situation implies that government hospitals and health infrastructural facilities are relatively inferior, contributing to poor health status in the country. In addition to these problems, there are significant regional disparities in health status and infrastructure.

Owing to a shortage of tertiary level hospitals at the taluka level, insufficient beds, and a scarcity of healthcare staff, many socio-economically underdeveloped regions in India struggled to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic (Bhat, 2020). Therefore, it is vital to explore the experiences, challenges, and psychological problems of clinical and non-clinical health care workers face in economically underdeveloped areas and understand the type of social support system they received to reveal grass-root-level issues that are otherwise overlooked. The study findings can thereby aid in developing intervention strategies to improve their quality of life.

Kasturi (2018) describes the challenges faced by the healthcare system in India and states that the absence or “crunch” in human resources or power is one of the biggest challenges in the healthcare sector. According to a Ministry of Health report, one government doctor available for every 11,082 people, one government hospital bed for 1844 people, and one government hospital for every 55,591 people. This situation indicates the critical state of the Indian healthcare system (Chandna, 2018). In addition, India has approximately 20 health workers per 10,000 inhabitants, and in the state of Karnataka, this figure lies between 16 and 22 health workers per 10,000 inhabitants (Rao et al., 2011). Prominent healthcare officials understood and emphasized the burden and challenges faced by HCWs. On the “Doctor’s Day” prior to 6 months of the onset of the pandemic, they opined that multiple factors, such as a dearth of healthcare professionals, lack of proper infrastructure, and high inflow of patients had forced doctors in India to function in a highly challenging environment (Biospectrum, 2019).

The unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic affected the entire world. In India, from January 3 to November 4, 2020, there were 8,313,876 confirmed cases and 1,23,611 reported deaths due to COVID-19 (WHO, 2020c). India’s health care system, which was already in crisis, was further hit because the pandemic took its toll on HCWs by placing them in a more challenging environment. The extremely high number of cases, scarcity of resources, and the need to follow strict guidelines impacted the HCWs’ professional life, physical and psychological well-being (Greenberg et al., 2020). Regional disparities in health status and infrastructure compounded the challenge. Previous analysis has shown that the H-K region has relatively fewer district hospitals, a lower number of primary health care centers, and fewer beds, all of which contribute to poor access to health facilities and poor health status (Siddu et al., 2012).

HCWs provide care and services to the sick and suffering, either directly as doctors and nurses or indirectly as caregivers, technicians, assistants, or medical waste management staff (Mohanty et al., 2019). Ample number of studies are found on clinical health care professionals [doctors and nurses], but there is a dearth of studies on non-clinical healthcare workers [lab technicians, Group D staff, and security], although they have played an important role during COVID- 19 (Chandra and Sodani, 2020). In this context, considering both clinical and non-clinical HCWs, the present study used a qualitative approach to understand the experiences, challenges, psychological well-being and needs of H-K region HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design and participants

The present research used a qualitative method to explore the study objectives. The study used purposive sampling to recruit participants (HCWs working during the COVID-19 pandemic). The 221 chosen participants were HCWs (doctors, nurses, Group D workers, security guards, ambulance drivers, and lab technicians) working with COVID-19 patients in government hospitals in the H-K region. The study’s inclusion criteria were: (i) HCWs working with COVID-19 patients and (ii) HCWs working in government hospitals in the H-K region.

Procedure

HCWs who expressed their interest in participating in the study were chosen. Semi-structured interviews (Table 1) were conducted with HCWs who agreed to participate. The HCWs (N = 221) were asked to reflect on their experiences, challenges, needs, psychological well-being, social support systems, and the coping strategies they used during the stressful situation of working in COVID-19 wards during the pandemic. The interviews were translated from Hindi and Kannada and transcribed into English. The transcribed data were analyzed using conventional content analysis (Hsieh, 2005) to derive codes. The codes were further sorted into sub-categories based on inter-connections and associations. These sub-categories were organized into meaningful clusters of categories. The 63rd transcript reached data saturation. The study researchers participated in all the data analysis processes, and external experts in the field validated the analysis.

Results

This study holistically attempted to understand the challenges, psychological problems, needs, social support, and coping strategies used by clinical and non-clinical frontline HCWs working in government hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The study used purposive sampling to recruit 221 HCWs (doctors, nurses, Group D workers, security guards, ambulance drivers, and lab technicians) working during the COVID-19 pandemic. The majority of HCWs were males (58.4%), married (56.6%), and had two children on an average. Most HCWs were graduates (34.8%) and a significant number were nurses (45.2%) (Table 2).

The large sample size provided an opportunity for an in-depth exploration of the challenges, psychological problems, needs, and social support experienced by frontline HCWs working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our analysis of the interviews revealed three main themes: (1) experiences and challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic, (2) psychological well-being and coping strategies of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and (3) experience of and need for social support among the HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic (Table 3).

Theme 1: Experiences and challenges faced by HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic

A. In the workplace

-

(i)

HCWs initial experiences of working in a COVID-19 situation

In the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the HCWs were unaware of the nature and consequences of the illness. This lack of knowledge was found to increase fear and anxiety among them. Initially, there were no fixed protocols and treatment plans, which added to their apprehension. The HCWs indicated the need for psychological support in the initial phase of the pandemic as a majority expressed fear and anxiety in working in such a situation.

“During the initial period of COVID-19, we were not aware of how it was spreading, so we were afraid and worried about its mode of transmission” Line 45, P20ViPa

“In the current situation, everything that has happened, transpired because this disease was new to us in the initial days. How it spreads, how to protect ourselves, how its efficacy is was a mystery. Initially, we were anxious as things caused more infections, and then by and by we became less anxious.” Line 62, P14AlGa

“In the beginning, even I didn’t have any idea about COVID. So, I also didn’t know what to do. We were also confused regarding treatment and protocol …starting, there were all kinds of problems were there, and I had never used a PPE kit before.” Line 4, P9AlUK

“I was scared of getting infected… and others were telling each other…. so many people are dying, and we are working here’… That time I was scared.” Line 36, P20SuDe

Media portrayal of the pandemic increased fear among the HCWs and their families. A majority of the family members were against the HCWs caring for COVID-19 patients and insisted to quit their jobs. The HCWs were forced to choose between these family fears and their duty towards the community. They saw their patients as family members and their work as a duty to serve society (see quotes P9ViRa and P3ViSL).

“Initially, there was some fear because of the way the media exaggerated the fear aspect of this disease, and it used to come in the newspaper also. Most of the fear came from the publicity that the media and the newspaper gave.” Line 208, P12AlDe

“Usually I stay away from my parents. During the initial days of the pandemic, like everyone they were worried as well. But they started panicking watching news channels about the situations and they insisted on me to quit the job. Somehow I had to tell them that the situations are not to the level that media channels are portraying and I told them that it was not possible to quit the job.” Line 184, P9ViRa

“Initially, they suggested not to go to work, and I thought of patients as family members, and we have to treat them, and I have been telling them that we have been provided with PPE kits, masks, etc., so we will not get Corona and educated them.” Line 74, P3ViSL

“Some…they said ‘why are you doing work …don’t do work, let’s see what will happen’ but I made them understand that as a doctor, as a professional I have to work and it is my job.” Line179, P9AlUK

The HCWs educated their family members about the preventive measures to protect themselves from the infection. In some cases, the HCWs masked their feelings and anxieties to mitigate their family members’ feelings and worries.

“As people at home were really unaware of things, how exactly things happen at the work, they didn’t want me to go home after COVID duty. After explaining the precautionary measures that we follow during duty like maintaining distance and all, they realized and understood that we are not in direct contact with patients”. Line 30, P4SVS

“Sometimes we need to mask those fears and anxiety with family members because they will feel anxious when we showcase our fear or anxiety, and other professionals also feel frightened if I say that I have worked with COVID patients.” Line 164, P9ViRa

Furthermore, the HCWs reported experiencing resource scarcity during the initial stages of the pandemic as the healthcare system was not adequate to handle such a situation. Due to the lack of protective gear, the number of staff working in a given shift was reduced. Moreover, some HCWs quit their jobs as they found it too much challenging to work in such crisis situations. Hence, the scarcity of resources and reduced staff were found to increase the burden on the available HCWs.

“Earlier there was lack of resources because this COVID started so suddenly, earlier we had a lack of resources, PPE and all. It never gave a sign that it would come so fast.” Line 88, P17AlSh

“In the beginning, we had a problem with managing because we had very few resources. It was not anyone’s mistake. But we had very few resources. We had to adjust because we would have 2 PPE and four staff for that shift. So we had to adjust. One person had to be in the PPE for a bit longer time. Only if the person was interested in doing that…only in the beginning. Now we have a lot of resources, and there is no such problem.” Line 90, P17AlSh

“It began from March, at the beginning, many people left because they couldn’t adjust to the situation of wearing PPE and working; now it is okay, we can manage the process.” Line 6, P3SVD

In summary, in the initial stage of the pandemic, HCWs reported heightened anxieties due to a lack of knowledge about the illness and the required treatment protocols. Furthermore, family members also reported high apprehensions and pressured the HCWs to quit their job. It forced the HCWs to choose between their duty and their family fears. Additionally, an underprepared healthcare system and shortage of staff and resources were found to increase the burden on the HCWs.

-

(ii)

Onset of a pandemic vs. a new normal

A majority of the HCWs reported heightened anxiety in the initial phase of the pandemic; however, such worries were found to reduce gradually, and the situation normalized as the HCWs encountered more cases. In the early days of COVID-19, healthcare workers were anxious because of certain aspects such as lack of knowledge about the infection, lack of predefined treatment protocols, and the exaggerated depiction of COVID-19 in the media. With time, they gained more information and knowledge about the infection. They were provided information regarding the usage of protective gear, which helped reduce their fears and anxieties. Moreover, after treating several patients with similar conditions, the HCWs followed a treatment routine, which reduced their challenges.

“I was scared in the beginning a lot, and then again we had to face everything, now it has become normal…because most people are getting infected.” Line 42, P1AlJy

“Initially I had extreme fear as there was a high death rate in other countries so after I felt that we are the only persons to treat and care for them and we will be provided with masks, PPE kits to take precautions and to be safe, so now I am not having that much fear.”Line 30, P3ViSL.

“It is very challenging. First of all, we do not know much about this virus. We do not know what to do. We do not know what will help in these situations. As I treated more and more patients, I slowly understood and got ideas about what might help the patients. As of now, I make the patients do yoga and breathing exercises daily. It seems to be helping them, so I am happy.” Line 28, P8ViAk

“We did not know anything about COVID. Now we have some knowledge about COVID, and we also have experience. Earlier, we did not have any experience, and things were new, which is why we had fear. But now we know what to do (treatment and precaution) in a given situation, and we are adjusted.” Line 66, P15AlSa

-

(iii)

Working in a new environment

With the escalating number of COVID-19 positive cases, there was an increased need for workforce to provide medical treatment to patients. Medical students and interns were urged to volunteer for COVID-19 duty. Meanwhile, even experienced HCWs were unfamiliar with working with infectious diseases, which placed them in a new working environment and forced them to administer medical treatments without prior knowledge and/or training. They were expected to learn on the field by observing seniors and other HCWs.

“Actually, in ICU we use some machines like HFNC …. Before, I didn’t know anything about this machine, after this pandemic, I have learned how to operate it…it is beneficial to for patients before going for ventilators ….. It is working well, and patients are also recovering” Line 116, P7ViNa

“Yes …it is related to COVID patients…I couldn’t do cannulation before because I am a fresher, but now I wear PPE and go inside; I do it now with ease.” 110, P13ViCh

“At the start, when I had duty in the MICU, I would feel that work was difficult because I had no experience working in the MICU. But I now know, so I do not feel anything like that.” Line 102, P11ViMK

-

(iv)

Working for the greater good vs work as a necessity

The HCWs reported that they saw their work as an act for the greater good. Their contributions during the pandemic were seen as a privilege and a work of God. This act was seen as a pro-social behavior to serve others and not give in to one’s vested interest.

‘Whatever the work I do, I give it a hundred percent, and I am devoted to this work, and I see God in this work.” Line 96, P1AlJy

“I am feeling proud and great because, in the situation where everyone is avoiding COVID-19 patients, we are treating them with care, so it feels great to work.” Line 150, P3ViSL

“Whatever the work I do…wherever they post me…..I don’t do it for money…I feel that I am serving others, and it’s a privilege to do that.” Line 176, P31ViCh

The HCWs rationalized the problems faced when caring for patients. They thought of themselves as “frontline warriors”. Hence, they believed that suffering and sacrifices were a part of their duty to serve society as warriors.

“Yes …I miss parents and the bonding between us …. That’s why they have given us the tagline as ‘ Frontline Warriors’. We have to save lives by stepping in, so we are doing that.” Line 97, P9AlUK

“Wearing a kit was problematic, but we still did our duty. Whatever our struggles may be, serving the public is more important. They should not face any issues, which is how I continue doing my duty. Line 78.P9SuSa

I have to do it, madam. The government has given me a job; now I have to do it. Serving the public…” Line 76.P9SuSa

They experienced positive energy and motivation to work despite several challenges such as exhaustion due to work, personal protective equipment (PPE) problems, and increased workload.

“We get some positive energy…during that time, we do feel physical exhaustion, but in this pandemic, we are working, and I feel proud of myself.” Line 387, P12ViVg

“Especially nothing much ….as a doctor you don’t have many options…when you have duty you have to go whether you feel stressed, anxious…it doesn’t matter, when you see a patient dying in front of you. We have to treat, and we have to do work with our maximum potential….if we save someone, that is the reward itself …” Line 187, P9AlUK

Some HCWs expressed doubts and fears in serving in such critical situations. However, their perception of working for the greater good motivated them to work in risky situations. The outcome of treating patients and saving lives motivated the HCWs and provided a feeling of satisfaction in carrying out their duty.

“As a health worker, I have a proud feeling that I am working for the people in this tough situation, and sometimes I feel wishfully that I would have rather been resting at that time like others, but in reality we have the privilege to care for others, that feels great.” Line 80, P3ViSL

“To be frank, I felt doubtful whether I made a mistake by joining this and that I sometimes used to think…after all my patients got discharged I felt happy and kind of satisfied to be a doctor.” Line 24, P7SVSa

“In the beginning, we were thinking like ‘why we have to do’ we were not ready to work out the whole batch, but after that we understood. As a doctor, we should not show our back to the patients. If this kind of situation happens, we should step in and work. We asked for our facilities, and they said they would provide. We felt this was enough that time but now okay.” Line 177, P9AlUK

Some HCWs continued to work as a necessity to provide for family members. Hence, working through the pandemic was not just an intrinsic motivation to engage in pro-social behavior; for some, it was the only way to provide financial support to their family.

“I have to run the household, so I have to bear it; I work in the hospital under the roof; few people have to work in the fields, and a few of them lift heavy weights…. their work is harder than mine.” Line 46, P1SVS

“If we want the job, then we have to do it; some people don’t want to do it - that is their decision. I want this job, so I have to do it.” Line 76, P1SVS

“Our children are studying, so we need to have the financial support—so we don’t have any option so, even though I experience fear, I do my duty for my family.” Line 40, P1ViSh

In summary, the HCWs saw patient care as a work of God and thought of themselves as “frontline warriors”. This attitude of working for the greater good motivated them to serve during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, some HCWs saw this as a necessity to take care of their families. Hence, some were motivated by altruism, while others were motivated by the need to provide for their families.

-

(v)

Challenges faced by HCWs while serving COVID patients

Problems arising from the use of the protective gear

All of the HCWs found it challenging to work in protective gear. The challenges faced by HCWs when wearing PPE and/or protective gear were: (i) Physical problems, (ii) difficulty in working, and (iii) problems in communication. Working in PPE was found to take a toll on the HCWs’ physical health. They reported physical problems such as breathing difficulties, drowsiness, skin rashes, sweating, and body ache. They also reported higher allergies due to the usage of N95 masks. They experienced a loss of energy due to dehydration and working while wearing PPE. Female HCWs reported more urinary tract infections and difficulty maintaining hygiene during menstruation.

“When you wear a PPE kit, it feels like you have been locked in a dark chamber. Because no oxygen is coming in, the CO2 we breathe out is not going out. So much sweating happens that it feels like you are standing in water. Suffocation happens.” Line 91, P10AlRS

“Personally when we wear PPE, if we are wearing the one for too long then it will at times cause headache, breathing problem, or energy loss because sweating is more in PPE and from the patient’s side sometimes they are aware also and irritating at times” Line 6, P7AlDi

“As women, we will be having some problems (periods) in which we will be using washrooms often, so at that time, we face difficulties when we have the PPE on.” Line 90, P4SuAs

“We had to control our washroom needs, and I had UTI once. Usually, I am the kind of person who drinks a lot of water, so I need to go to the bathroom frequently. I think it is because of this that I had to limit my water intake, to control my washroom needs. I think it is because of that, I am not sure, that; I had UTI once or twice.” Line 110, P17AlSh

Multiple layers of protective gear made it difficult for HCWs to carry out routine medical procedures such as intubation, cannulation, and palpation. The use of face shields and PPE led to fogging, which restricted their vision and inconvenienced them when tending to the patients.

“Yes. Even putting a simple IV line has become difficult. You cannot make out anything. Even if you want to feel, you cannot feel anything because you are wearing three layers of gloves. So, you will have to keep pricking repeatedly. The patient also starts getting irritated when you have to keep pricking repeatedly. There are a lot of procedures. One is drawing blood, and another is doing blood EBG, or investigations, or IV. These irritate the patients a lot. But mainly, drawing an IV line is difficult or intubating the patients. We cannot make out minute details like rashes or anything. At least through touch, we can find out if there are rashes or anything. But now it is difficult to find that out.” 71.P14AlGa

“I will use hand wash…. Actually, the problem is after wearing gloves, we can’t palpate the veins, and you can see also …. After wearing MID-5…it tends to peal skin near my specs, it is a bigger problem if the staff are wearing specs.” Line 96, P10ViFa

“Literally, we were shaking like this (Shaking her head), and we were trying to see. Very difficult… a horrible situation, especially when I was working in a NICU. So for putting that Cannular, we were suffering very much. With PPE and all, the first two-three months, it was horrible. Working with PPE…”Line 142, P22ViBA

Along with difficulties in carrying out medical procedures, the HCWs reported difficulty in communicating with the patients. PPE was found to be a hindrance in conversing with patients. The HCWs found it difficult to talk and listen clearly to patients. Hence, when compared with routine medical care, care during the pandemic impacted communication between medical staff and patients.

“What I mean to say is …while wearing PPE …from the patient side, there will be a lack of coordination… They will sometimes misbehave…. and we are wearing PPE, and we can’t hear properly…” Line 239, P12ViVg

“Yes, we can’t do that too…. And we are not contacting the patient directly… we will cover ourselves with PPE…. We cannot hear what they are saying, and fog will be there making it difficult to see them properly …so there are all kinds of problems.” Line 62, P13ViCh

“We wear face shield …. At times when I talk to patients and try to give assurance that nothing will happen …sometimes I couldn’t talk to them.” Line 84, P13AlMa

In summary, wearing multiple layers of protective gears was found to impact the HCWs’ physical health (breathing difficulties, drowsiness, skin rashes, sweating, and body ache) and cause problems in performing basic medical procedures (such as intubation, cannulation, and palpation) and converse with patients.

-

(vi)

Working beyond the scope of assigned roles

Another challenge faced by the HCWs was working beyond their capacity. The HCWs worked long hours and had to take care of a higher number of patients. One of the reasons for working beyond their ability was the lack of staff availability. As evidenced by participant P14ViKa, work pressure was high as many staff tested COVID-19 positive, which strained HCW availability. The situation also made HCWs perform treatment procedures that were not part of their job description.

“There will be 5 members in one slot, and there are two wings called A wing and B wing; so, we had slots of four hours in which one staff from A-wing and one staff from B wing should work in ICU, and there is no replacement when the nurse is absent. So, when I was in ICU, I had no partner because he tested positive for COVID, and two deaths happened that day.” Line 78, P14ViKa

“Actually not much because, during internship time, we had day and night duty - so they had followed the same but yes due to COVID even we had 24 h duty.” Line12. P14AlGa

“It is true, that we were working beyond our capacities. We had to go to the markets and other places. Each day we had to collect around 70–80 samples, which was not at all an easy job Only we know how difficult it is to wear PPE kits for almost 24 h.”Line 80, P14SuSu

Along with administering treatment and medical care to patients, the HCWs working with COVID-19 patients had to assist with their daily hygiene. In severe cases, the HCWs even helped with feeding the patients. Some of the reasons for HCWs to undertake these activities beyond their assigned tasks were the unavailability of family caregivers and the scarcity of staff.

“Hmm yes…some patients are weak, and we have to feed them, and I take care of them like I take care of my own kids.” Line 148, P6ViK

“Challenges faced at work. We don’t allow any attendee; one staff has to attend 15–20 patients. We do whatever - medical –everythingwhile wearing the PPE kit also—3 to 4 h we have to take care of 20 patients at a time—everybody will have a complaint, and that’s an issue.” Line 84, P23ViMK

In summary, HCWs reported working beyond the scope of their assigned roles. They were expected to help patients in their daily hygiene routines. The HCWs reported experiencing higher work pressure because of the shortage of staff and the absence of family caregivers.

-

(vii)

Scarcity of resources and manpower

Due to the unforeseen demand for resources, the healthcare system faced a tremendous scarcity of resources. This scarcity impacted the patients and HCWs. The HCWs experienced a scarcity of protective gear such as PPE, gloves, and masks. The shortage of protective gear compelled the HCWs to use and reuse the same PPE for long working hours and use cloth-mask substitutes. This situation led to an increase in the risk of infection and skin allergies among the HCWs. In some cases, they had to rewash the PPE kits and reuse them in subsequent shifts.

“Yes madam…Sometimes it will be wet with perspiration inside the PPE kit. Sometimes it will be difficult to wear continuously, and we will get skin infection. They used to tell us that ‘ we will give only one. They will say that there is only one mask for a shift and can’t give extra.” Line 114, P13AlMa

“So, we would go in and do our work. But back then, kits were quite costly, and we would not get them. And then, we were not given N95 masks. We used to walk around with their cloth mask or surgical mask. When it all came to an end, the fear went off. We did our duty without any fear.” Line 64, P12AlDe

“Hmm yes…We can clean a few kits … I will use the cleaning machine at that time, and we have different equipment to clean and wash products….I do the cleaning daily…..they gave 4 kits for a month…… I clean previous one and keep that one for drying….next day I will use that…” Line 170, P6ViK

Shortage of staff and increased numbers of patients increased the burden on the HCWs. Some of the reasons for staff shortage were: staff being infected with COVID-19, unwillingness to serve in COVID-19 pandemic situations, and resignations. As there was a shortage of PPE kits, only a few people could work in a given shift.

“One staff can manage maximum 6-7 patients…But we both have managed 40–45 during that necessary situation, we need a minimum of 6 staff at each shift.” Line 256, P13AlMa

“there were insufficient staff…..a few of them joined recently…old staff’s got infected and they left due to COVID….as an in-charge I have to work …so I worked” Line 68.P2AlAK:

“There is work pressure. Before I used to do work normally without any encumbrances but now I have to wear the kit and do it. And at any given time, only 3–4 of us will be inside, so obviously, the pressure builds upright? The reasons are that there are a lot of patients but only a limited staff. So the pressure builds up.” Line 290, P27ViRa

There was an increased demand for infrastructure: beds, oxygen supply, basic facilities, and intensive care. One HCW reported that when the cases peaked, the need for facilities (such as oxygen supply ventilators) was high. However, they could not provide these facilities to all patients, placing them at risk.

“Ah…Resources also, because sometimes patients need high flow oxygen and a greater amount of oxygen. Many machines were not available here. Or sometimes there may be some (Voice unclear). So, at that time we desperately needed more machines. At such times we had to watch people dying without oxygen. We couldn’t do anything at that time.” Line 152, P16ViDL

Yes, now also we are lacking things because in some areas, especially we don’t have much oxygen supply and Oxygen poles. We are facing many problems, many problems mean in a sense…. Umm…as an OBG NACU staff I can say that there is no facility for hot water. Now-a-days it is getting colder, so the patient can’t bathe in hospitals because there is no hot water source there. In some areas, we lacked Oxygen poles. So if any patient requires a sudden oxygen emergency, to pull this to that bed that side, that bed to this side. So, unnecessary extra work we had to do. And if some patient needs a ventilator, in the present situation it is okay, as the patients are not as many as during last month or before that At that time when more patients were getting serious meant hell for us and we faced endless difficulties.” Line 504. P22ViBA

In brief, a shortage of resources, infrastructure, and staff placed an extreme burden on the HCWs. As there was a shortage of protective gear, the HCWs were compelled to re-use them and/or substitute with less effective materials such as cloth masks. This scarcity of infrastructure was found to increase the burden on HCWs and increase the risk of patient mortality.

-

(viii)

Communication issues

Communication barriers were observed between doctors, patients, and family members. Along with communication difficulties due to PPE use, HCWs also faced problems in explaining the COVID-19 protocols (and the need to adhere to them) to patients and their caregivers. As most of the patients were asymptomatic or had mild symptoms, they could not understand the need for adhering to the treatment protocol. This situation led to an increased risk of accidental injuries and death in some cases (See P16ViDL’s quote).

“We explained and convince them that if they do not maintain distance with us, then no doctor or nurse will come to treat them and that in the end, they will only suffer. We told them that whatever we do and whatever we ask them to do was for their good. We spent so much time and effort to make them understand, but they did not even try and understand. We did it for them only, but they failed to even understand.” Line 46, P15ViSh

“Though the PPE kit has helped us in a lot of ways, however, we had confronted a few inconveniences because of that. I had insufferable sweating, in addition to that, elderly patients found difficult to understand what I was trying to convey to them. Yet another major problem was to make patients understand the importance of adhering to COVID-19 precautions or how to contain it. Despite working continuously, the patients failed to follow our instructions, which led us to instruct them repeatedly to wear masks which I felt was an exhaustive job”. Line, 152, P13SuGu

“All the people were very healthy; they had some breathing problems only. So, as per the norms set for them we had to tell them to urinate and defecate where they lay into the pans provided for the purpose. But the patients were young 30 or 40 years old men. They were very reluctant to comply to our instructions, and insisted on going to the washroom. So, individually speaking, whatever we tell, he won’t understand. Then he will go to the washroom without oxygen. We can’t supply oxygen in the washroom. So, sometimes I have seen some people have died in the washroom owing to their lack of co-operation, for lack of oxygen. He is strong and stable with oxygen, but without oxygen, he can’t survive doing whatever he wishes….” Line 154, P16ViDL

In the Indian healthcare setting, the family plays an integral role in communication and making healthcare decisions. In a collectivistic culture such as India, the family acts as a mediator and provides most care to the patient. However, during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients were quarantined in hospitals and institutions to control the spread of the virus. Even with the need for physical isolation, the families were unwilling to leave their patients alone in some cases. They wanted more information regarding the treatment being given to their loved ones. This increased the burden on the HCWs who had to enforce protection protocols and engage in communication between the patient and their caregivers. In some cases, this restriction acted as a barrier to communicate information between multiple stakeholders (doctors, nurse, patients, and their family members) (See quote P17AlSh).

“Here it is a little different. When there is a COVID patient, one of their relatives will come, and they will start advising us on what do to. It becomes very difficult to handle. But what can one do? The security system here is like that…” Line 378, P27ViRa

“They used to say that they would go in and meet the patient without wearing PPE kits. But then we started telling them that we would not let them in if they did not buy a PPE kit and come. We tried our best to make them understand. We would end up explaining the course of COVID also to them. To make them understand, we would try and explain the course of COVID by giving many examples and trying to convince them. We used to show them treatment visuals and tell them what we have done. We used to give them examples of doctors who had become patients. There were many cases here of doctors who became patients. We used to tell them that they also aught to be most cautious and be covid free.” Line 53, P14AlGa

“Of course, because here there is no ultimate medicine. We have not found an ultimate medicine for COVID. So, it is a kind of symptom management. For breathlessness, we give medicine; for fever, we give medicine. So, these are the management levels and tricks of saving the patient. Sometimes, there is a lack of proper communication between the patient, family members, nurse, and doctor because there is a barrier. Because, they cannot go inside and directly talk to the patient. So, there can be a miscommunication or false communication when the information goes from one side to another. So, because of that, there can be some problems. The patient may say no, the doctor said this to me. The patient might call the family members, and they will come and talk to the doctor about something else; the patient will get to know something else. At that time, there will be a lot of confusion on what to do.” Line 158, P17AlSh

Mild symptoms and a lack of knowledge regarding the illness increased dissatisfaction among the patients. The patients were found to express their anger and dissatisfaction to the HCWs. The patients saw several factors such as staying in isolation, inability to meet family members and interacting with HCWs in PPE kits as unusual. Hence, this situation also increased patient anxiety.

“Some people were scolding us that you’ve admitted us despite having no problem, and you are harassing us, so we informed them about COVID and how it can harm their family as well as their neighbors.” Line 60, P13SuGu

“At that time, we will find some difficulty because the patients will say no no….insisting.. I do not need these medicines. At such times, we will find it difficult to control the patient, to help arrive at a decision. And when the patient is not well, when he needs oxygen, but the patient wants to go home because some people are afraid of hospitals. Especially when they are alone inside the ward as no family members are allowed inside. Moreover, with older people, they will be like, I want to go home. They don’t see us as normal human beings. We are wearing PPE. They will be seeing us as aliens. They will be afraid. They may need oxygen. They cannot go home without an oxygen supply, and we have to struggle hard to make them understand their need to be here. They think that we are keeping them here unnecessarily and all that.” Line 160, P17AlSh

In summary, a lack of understanding of COVID-19 protocols and the presence of mild-to-moderate symptoms increased dissatisfaction among the patients. Additionally, isolation and seeing HCWs in PPE kits increased patient anxiety. These situations heightened communication barriers between patients, caregivers, and HCWs.

-

(ix)

Violence against HCWs

Another major challenge faced by HCWs was the violent behavior of patients and family caregivers. The unpredictable nature of the new infection increased the burden on the available HCWs, and a lack of specific treatment impacted the patients and their family members. They doubted the healthcare providers and believed that the treatment provided was inadequate. This lack of knowledge increased violent behavior among patients and family members.

“We try our level best, but patients will think that we didn’t do well enough, and they will start abusing us, such things will disturb us.” Line 48,P2SVSP

“The treatment what we are giving, we give it according to the protocol or whatever is planned. But the patient’s satisfaction… it’s up to his improvement status. Some are diabetic and all will not improve easily. But the family members will think differently. They may think that proper treatment is not given. They blame the hospital, and they blame doctors. That is the very worst part of this. During the pandemic, nobody should blame any doctor or any hospital.” Line 44, P16AlAr

“First of all, we had compromised a lot in terms like we were provided with bad quality of food, we worked without salary on time for long periods. We still continued to work because we understood the difficulties that everyone was undergoing. But what makes us feel more challenging was that sometimes we had encountered anger issues with patients. They used to express anger on us for instructing them to follow what they are supposed to do.” Line 104, P1ShRa

“Basically, my job was to visit the village and collect test samples. Obviously, I wore a PPE kit. Excessive sweating caused by wearing the PPE kit was a problem, but another big problem was the villagers’ reaction. Because, they don’t understand why we go there and take their samples for testing. They go the other way, thinking we are unnecessarily testing them and or they think we wouldn’t give valid test reports. So they were not co-operative. What was more hurting was that, they behaved rudely with us, and they by no means hesitated to scold us and they also tried to hit us.” Line 38, P14SuSu.

The HCWs reported that they were constantly blamed for the patients’ deteriorating health and at times faced verbal and/or physical abuse.

B. Family-related issues faced by HCWs while serving during the pandemic

-

(i)

Fear of infecting family members

Fear was seen as a common emotion among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most HCWs expressed the fear of infecting their family members. A majority of the families comprised members categorized “at-risk” (such as the elderly and people with comorbidities) and young children. To ensure the safety of their family members, HCWs followed protective protocols and preferred staying away from their families. In some cases, the HCWs were unable to maintain physical distance owing to living in smaller houses, thereby increasing the risk of infecting their family members.

“I have small kids, and if I infected patients also, that will be an issue…..My parents live with me… they are old, and my kids are small. I was scared like what if I infected them….so when I used to go inside the home the first thing I did was to take a bath…” Line 38, P2AlMa

“My grandmother and grandfather are at home. Nothing should happen to them. Old age people are more prone to getting this infection. That is why I have not gone home because otherwise, it would have been a problem.” Line 108, P9SuSa

“Confusing thoughts in a sense, see ma’am, we bring and drop positive patients, but doctors say a lot of things about this virus-like it transmits through touch. So, I was nervous, if it happens to me, let it happen, but nothing should happen to my family, and that is why for 4 months I have not gone home.” Line 112, P9SuSa

To sum it up, one of the main fears of the HCWs was infecting their family members. HCWs ensured that they followed all safety protocols to protect their family members.

-

(ii)

Inability to spend time with family

The HCWs reported an inability to spend time with their family members. Those who stayed away from their family found it difficult to meet family members. For example, P13ViCh stated that they could not meet family members for almost 11 months. In some cases, the families stayed at a different location from that of the place where the HCWs was staying, and in some other cases the HCWs chose to stay away from their families.

“Yes….I have never been away from my family for so long …I have visited my family in December, and it’s been 11 months now…I had planned to go in April but due to COVID, I couldn’t visit.”Line 94,P13ViCh

“I cannot spend much time with family and I can’t meet them whenever possible…..I have to work in a hospital ….I took a room here and stay there.” Line 132, P13AlMa

HCWs who stayed with their families could not spend time with their family members. They reported that they could not spend quality time with their family because they were afraid of infecting family members. Therefore, the HCWs stayed in a separate room away from their family members. Along with a fear of infecting others, increased workload and long working hours restricted them from spending time with their family when compared with pre-pandemic times.

“Ever since the last six months, I have not been giving much time… what I do each day when I go home is, I take a bath and I close myself in my room….I feel that I am not spending quality time with my family…. Previously I used to reach home by 6 and we used to talk till 10… But now my parents are old and I have a fear that they will also get infected so…now I am not spending much time…” Line 173, P2AlAK

“Yes, I am away from my children and husband because I’ll be having duty here and after duty, I’ll be in a separate room so I can’t talk to them or spend time with them; I am in touch with them only through phone calls and video calls.” Line 130,P4SuAs

“Since work timings have increased, I have not been able to give enough time at home. My mother is also aged. Because I work from 8 to 8, sometimes going home and having dinner also gets delayed. And because there are only two of us, one does not eat without the other. Because of this delay in having dinner, my mother faced some health issues.” Line 26, P15ViSh

In brief, increased workload, working in different geographical locations, and the fear of infecting family members restricted HCWs from spending time with them.

-

(iii)

Family responsibilities vs. performing duties

The increased demand for HCWs and healthcare risk impacted their personal and family life. A majority of the HCWs reported that their family members were scared of serving in life-threatening situations. They said that their family had suggested quitting their jobs in some cases. This has forced the HCWs to choose between giving into family fears and serving the patients.

“They told me to quit the job and come home and live peacefully. I told them that COVID is a normal disease and nothing would happen to me. We have been taking precautions about COVID -19, and this disease will not continue till beyond one year; we will get vaccine shortly.” Line 233, P14ViKa

“When they heard all sorts of facts about COVID, they got scared and asked me to leave my job. But then I told them that nothing would happen and asked them to stay strong. After that, they agreed, you have been given a job, go do it. Line 348, P9SuSa

The HCWs were found to juggle between their roles and responsibilities. Increased demand on the work front impacted their family responsibilities, and their inability to undertake these family responsibilities affected them emotionally (expressed as feeling sad or losing their temper). In some cases, the HCWs contemplated resigning from their jobs.

“Yeah.. So, we have to work here by wearing a PPE kit, and we will become very tired. Then after coming there… at home also we have so much work…we have to do everything. Mm… mm… During that time, a lot of dehydration occurs. So it is challenging for us to work in this COVID wearing PPE.” Line 96, P16ViDL

“My relatives also, they keep saying that you go to duty and your mother has to be alone at home. But somehow, I just have to manage. I used to often feel as to when all this would end? I cannot look after my home also properly. My mother is alone at home.” Line 66, P15ViSh

“I told you I can’t manage my children’s study. I can’t concentrate on their activities. I can’t…. I’m now short-tempered. I become angry very soon. Whatever they say makes me very angry.” Line 385,P16ViDL

A constant tug-of-war was seen between family responsibilities and doing their duty as a HCW.

-

(iv)

Stigmatizing HCWs

Social stigma

Social stigma regarding COVID-19 was found to impact the HCWs. They were seen as infected and segregated from society. The HCWs reported that the community saw them from a different perspective (See quote P1ShRa). Apart from maintaining physical distance, the community created a social distance and treated them as untouchables. In some cases, the stigmatization forced them to vacate their rented houses, impacting themselves and family members.

“Yes, whenever I go to my village, people tend to say,,, “please don’t come near to me” and “be away from me “ and “ don’t come to the village “ we will be having only one day leave per week, so we do not have any time to meet our family.” Line 88, P1ShRa

“Yes, ma’am, I’ve faced a lot of issues like people were not willing and ready to talk to us, and they view us from a strange and different perspective. They see us as untouchables.” Line 104, P3SuSi

“No, I have not had any health issues like that. But even if I get a slight cough, I get scared, and wonder have I caught this virus? We live on rent, and we have had to shift a lot because I work in the hospital. People look at me and say, ‘she works in a hospital; we might get this disease because of her’. They have tortured us to leave our homes. We have shifted to a new home and have been there for three months now. Even though we do our duty in the hospital, we get treated like this.” Line 32,P15ViSh

“My thinking is like this. We are from outside, so we rent a room and live. When Corona started, the family that rented us the room and the neighboring people told us to move out. They were pleading, please leave; you are bringing Corona here.” Line 385, P10AlRS

The family members of the HCWs also faced social stigma from neighbors and the community. HCWs’ family members were also asked to maintain distance and stay away from others. The HCWs’ children were asked not to come out and play. It was found to negatively impact the HCWs, who stressed the need to increase awareness and reduce stigma in society.

“They didn’t interact with me… and they used to keep a distance from me …. Even the family members had said to my husband when he went to meet relatives ….they told him to sit far from them….that time we felt bad …” Line 243, P1AlJy

“They hesitate to contact us, as they fear getting the disease.. in the beginning, my kids used to play with others, but now they are not playing outside. In the beginning, a few kids used to come and play, but from the past 2 months, they aren’t coming because I work in a hospital; my neighbors also are fearful of getting COVID, and they are not sending their kids to play with my kids, so we are also not contacting our neighbors.” Line 36, P1SVS

Hence, HCWs and their family members experienced isolation and stigmatization from neighbors and the community. The society distanced themselves from the HCWs and their family and often treated them as untouchables.

Theme 2: Psychological well-being and coping strategies of HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic

A. Psychological well-being

-

(i)

Psychological distress

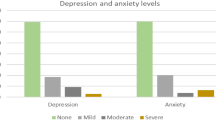

Most of the participants reported experiencing psychological distress while working during the pandemic. They reported experiencing anxiety and depression. Some of the factors that contributed to increased levels of distress were (i) fear of infection, (ii) increased workload, (iii) working in highly stressful situations, and (iv) social isolation.

“I was anxious that—what if I get corona after touching a patient? So, we did 12 h duty per day with that feeling.” Line 36,P1ViSh

“Yes, I feel stressed because I am away from my family, and I am exposed to the infection…”Line 106, P13ViCh

“Work is stressful. We are all the time-stressed dealing with the patients. Attenders, housekeepers, getting work from them is a headache.” Line 156, P17ViFa

“Yes, because we had fear, and we were staying away from others which caused me to be depressed for some time.” Line 90, P3SuSi

The HCWs also reported a constant fear and recurring thoughts of being infected by the illness. These repetitive thoughts were found to have a psychological (e.g., increased distress) and psychosomatic (e.g., increased palpitation) impact on them. The psychosomatic symptoms forced the participants to constantly worry and compelled them to undertake tests often to ensure that they were not infected. This constant fear of infection interfered with their work and their ability to provide satisfactory treatment to patients at times.

“After I came back, I started feeling doubtful again… I didn’t know if it was psychological or physical. I got those mixed and confusing feelings. I feared madam whether it would come once again or..will it be severe..It was all in my mind madam. So…I feel..sometimes…whether my heartbeat is increasing?” Line 44, P2SuIr

“Yes, we can’t care for patients as well as we would like to, as we know that they have COVID, and we can also get infected because of that, thus, we cannot give good care to the patients. We will try to do our maximum but…we have fear regarding COVID right. If he or she is a normal patient and if we don’t have fear, then we can care for and treat the patient well.” Line 48, P13ViCh

“As I had mentioned earlier, I had psychosomatic symptoms like a sore throat. Because of that, I even gave a COVID test three times. All three times, the result was negative. After that, I attributed them as psychosomatic and neglected it.” Line 46, P11ViMK

In summary, the HCWs experienced psychological distress due to various factors such as increased workload, stressful work and life situations, and fear of infection. The constant fear of the illness was also found to increase psychosomatic symptoms among the HCWs.

-

(ii)

Experience of loss and feelings of helplessness and guilt

The unpredictable nature of the illness, lack of expertise, and scarcity of resources had already placed a burden on the HCWs, which increased their feeling of helplessness in providing treatment. Additionally, increased patient mortality risk due to the illness and scarcity of resources led to the HCWs experiencing a lack of control over the treatment plans and patient health. Owing to the demanding situation, even HCWs with minimal or no experience in these situations had to provide treatment to COVID patients. It increased their feeling of helplessness.

“Being an Ayurveda doctor, I felt helpless, because at times this pandemic had demanded us to prescribe allopathic treatment under the guidance of senior allopathic doctors. There were some other situations where, in the absence of allopathic doctors I had to treat a patient though I was not comfortable with it” Line 218, P5SVGi

“Every patient believes in us, and they think that we will treat them and make them well again, but everything is not in our hands, and we just try our maximum and do our level best, even then if it is not possible then what can we do?” Line 30, P2SVSP

“Once it happened that, there was an emergency case, we immediately had to shift that patient to ICU. As it is COVID time we had to wear PPE, which resulted in a little delay in attending the patient. However, we tried to take him to the ICU and as the condition was serious we started giving him oxygen along the way. Unfortunately, no matter how many ways we tried the patient collapsed and took his last breath. We tried a lot with a lot of hope, but we could not save him, we were helpless there”. Line 142, P17AlSh

“In front of us, people are dying. We are helpless; we can’t do anything for them. So, the feeling the public gets is…. nobody is bothered, nobody is doing anything. So we feel helpless… Patients are dying every day; we see the death rate is very high, affecting all of us a lot. We cannot do anything for them. We are not able to save. ‘Jo bach gaya bache gaya jo gaya who gaya’.” Line 176, P17ViFa

In certain instances, the HCWs believed that they could have saved patients; however, the nature of the illness, scarcity of resources, and the need to follow protocols made it difficult to save the patient and reduced the HCWs’ control over the patient’s health. This, in turn, increased the feelings of guilt among the HCWs.

“We had a strong feeling of guilt because we were not able to give sufficient treatment to a patient even though that person was requesting us because we had a scarcity of beds, so, we sent him to another hospital.” Line 186, P4ViSu

“Yes, it did affect me a lot. The decision is not mine to take, but it makes us really sad when we hear such information. The patient needed it, and we could not help him. There will be guilt and regret.” Line 199, P8ViAk

“Yes, but unfortunately, we could not revive the patient, we tried our level best, but we could not do it. There is a feeling of guilt after the loss.” Line 26, P2SVSP

In short, a lack of preparedness, scarcity of resources, and the unpredictable nature of the illness increased feelings of helplessness and guilt among the HCWs.

-

(iii)

Need for emotional stability

As the HCWs were expected to work with COVID-infected patients, which was seen as the only way to deal with the pandemic, they believed that they needed to be emotionally stable to provide treatment and mental support to patients. Hence, despite their fears and anxieties about the infection, the HCWs reported that they needed to show emotional stability and courage in the face of the COVID-19 situations. The HCWs reported that they needed to consciously mitigate their fears and lay aside constant thoughts about being infected by the virus.

“We are with patients, so we shouldn’t be mentally unfit, so if we are confident and treat them with confidence, then they will enjoy a positive and a strong mindset.” Line 50, P1SuS

“In COVID, we have to accept the diseases… if you just cried COVID, COVID, COVID, that will have a detrimental effect in their minds rather, we have to accept we have to encourage them with the disease making them feel that we will treat and make their condition better… so this is the way we approach the patients… so that is there …if they can rely on us everything will turn out particularly good” Line 226, P17ViFa

“Yes, see, I also have fear. But I should not fill them with fear; I should fill them with courage.” Line 415, P18ViKa

-

(iv)

Positive attitude and self-motivation

The HCWs expressed the need for self-motivation and having a positive attitude. They believed that it was their choice to serve during the COVID-19 pandemic, and hence, there was a need to be self-motivated to work in the new environment and face adversity with a positive attitude. They also believed that their emotional reactions would impact the patients.

“Yes, nobody forced us to do or not to do the duty; we were self-motivated to do our duty, and also we have to adapt to family situations.” Line 38,P1ViSh

“As we continued our work with the patients, I’ve gained courage, and my fear has decreased because we shouldn’t be careless towards them because exerting positive energy will have encouraging impact on them, so I have changed so that we should be able to treat them well.” Line 267, P4SuAs

“Yes, because we had to face this situation and we have to fight against this virus,. So courage is necessary for us in every way, and this situation has helped us to show our strengths.” 216, P4ViSu

“No. I have the confidence that I can face everything, no matter how many patients are there. Even if one staff member is not there, we all have the confidence to manage. I also have that confidence. The others feel greater confidence when they see that I am there, then, together we can manage anything.” 137, P15ViSh

In summary, HCWs expressed the need to show confidence, courage, and a positive attitude while dealing with the pandemic and interacting with the patients.

B. Coping strategies used by HCWs

-

(v)

Emotion-focused coping

The HCWs reported engaging in emotion-focused coping to reduce work-related distress. They recognized their emotional issues and were involved in various well-being techniques (such as mindfulness, yoga, breathing exercises, reading books, relaxation, and listening to music). They also preferred to spend time with their family and friends. They shared their emotional issues with family and colleagues. They also sought social support (family, friends, and colleagues) to deal with distressing situations.

“Yeah. I tried to practice mindfulness. But I could not go with it for long. It always caused some disturbance in my mind. So, mindfulness is not a good thing, rather, it is not for me, I guess. So, I went back to the music way of relieving stress. I should go for some kind of stress relief practice; I don’t know, I will try.” Line 254, P17AlSh

“For me, I tried to spend most of the time on video call trying to be in contact with my family members, my kid and the other stress relieving channel for me is music. I think music has helped, especially for relaxation. So that is the thing I do when I wake up. That is the thing I usually do, and that is the thing that has helped me more. Especially during the quarantine period when I was very much isolated.” Line 124, P17AlSh

“I overcame these things by discussing with my friends, doing exercise, workouts, meditation and I used to ask others how they are dealing with these things and I used to correct myself and all those methods they were following mainly included things I was doing already - workouts meditations, reading some good books or listening to music or watch some good movies etc.” Line 171, P7SVSa

-

(ii)

Problem-focused coping

Some HCWs were found to engage in problem-focused coping. They developed effective cognitive-behavioral strategies that helped reduce workplace stress. They were found to compartmentalize their personal and professional lives and schedule and plan their time. They strategized to ensure spending time for their physical and mental health. Despite the stressful situation at work, they attempted to segregate work and home mentally. This mental segregation provided a temporary respite from stressful situations, providing an adaptive and healthy way of coping.

“When I am in my home, I think about home; work is everything to me when I am in the hospital. If I don’t know something, I will learn from others.” Line 249, P1AlJy

“We cannot carry work stress to our homes; we should leave it here…it does not mean that you don’t have to take this but to a certain limit is fine.” Line 220, P7ViNa

“You will have a schedule that from this time to this time, I will attend to COVID patients. Apart from those hours, out of 24 h, if you spend 4 h with COVID patients, in the remaining time, you can take time for yourself, for your hygiene, and mental health. You will have a lot of time in your hand; it depends entirely on how you want to spend that time. If I see a COVID patient in the morning and spend all my day thinking about that patient only, it will not help me. It depends entirely on you, how you want to spend that time and help yourself. Make a chart, make a timetable. Set your waking and sleeping time. Make your work your first priority. Make waking up, doing meditation, breathing, and breakfast and going to work your first priority—chart how you want to spend the remaining time. Do not leave any space for stray thoughts. If the thoughts do not come, you are safe. It is all in the mind. What is out of sight is out of mind.” Line 365, P8ViAk

-

(iii)

Religious coping

One of the other ways the participants dealt with stress was by keeping faith in God. They expressed faith in God and continued working in difficult situations. The HCWs believed that they would not be affected by adversity and would find the courage to deal with the crisis owing to their belief. This belief in God also helped them to maintain a positive attitude while serving during the pandemic.

“So many times ma’am, I have noted every time a patient gets positive, then, we will have a gripping fear that what will happen to us so, we will do work by believing in God, and we will do our work.” Line 180, P14SuSu

“In the beginning, there were limited patients…in the beginning when 2 cases were there they had sealed the district…next day there were 70 cases…I was scared because there were many cases…even if I had a terrible fear I believed in God and did my work.” Line 232, P13AlMa

“I have faith in God …I am working in this situation, and nothing happened to me…I feel that God is on my side, and I feel good.” 210, P13AlMa

“I completely believed in God that he will definitely look after me in any bad time whatever may happen, we were ready to face …so it was a comforting relief to us in that worst situation.” Line 82, P18SuMo

-

(iv)

Avoidance coping strategy

Some participants reported maladaptive coping behaviors such as stress avoidance and/or substance abuse. One of the HCWs suggested avoiding anxious thoughts and feelings and continued to work. They reported neglecting their thoughts and emotions. The HCWs were involved in risky health behaviors such as alcohol abuse and chewing tobacco in some cases. This was found to reduce their stress and help them sleep and relax.

“Anxious/!now I don’t feel anything. I feel, whatever happens, we have to move on.” Line 226, P19ViFa

“In the beginning when we heard of COVID, we were anxious, and we had to work then we had to be dedicated, so at that time we avoided the thought of anxiousness.” Line 246, P6AlAT

“Then, I was taking drinks ma’am (laughs) and after drinking I was going home and I used to sleep with relaxation. I used to be tired, and I was having pain in my nerves, so after taking drinks, I used to relax and sleep well.” 56. P6SuSh

In brief, the HCWs reported using adaptive (emotion-focused, problem-focused, and religious coping) and maladaptive coping strategies (avoidance and substance abuse). In applying adaptive coping strategies, they sought emotional support from family and friends, engaged in cognitive-behavioral strategies, and expressed faith towards God. On the other hand, HCWs avoided the situation by neglecting their thoughts and emotions by applying maladaptive coping. They were also likely to engage in risky health behaviors.

Theme 3: Experience and the need for social support among HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic

A. Experience of social support among HCWs during COVID-19 pandemic

-

(i)

Family and friends as emotional and instrumental support

The family was a crucial support structure for the HCWs while working during the pandemic. Encouragement by families and their emotional support was found to positively impact the HCWs, motivating them to work in the given situation. The family also assisted the HCWs in undertaking daily activities and, in some cases, even provided financial support. Often, the immediate and extended family helped the HCWs by taking care of their dependent children and by assisting in household chores while the HCWs were working.

“Since I started working, my family has never restricted or opposed anything, they have supported everything I do” Line 319, P8ViAk

“Our kids responded well and helped me in many ways during these difficult times. By the time I reach home they used to keep water and soap outside for me to get freshened up. My younger daughter was not happy to see me going to work, she was afraid of COVID-19, then I had to explain the need of working and as it is a need of the an hour to be more co-operative, so gradually she became co-operative. I am doing more work here (hospital) than my home, and I consider this hospital as my home and doctors are also showing care towards us, and I do not feel bored or feel like to quitting the job.” Line 106, P1ViSh”

“I can’t say community, but my family has helped me financially, and when I was not well, then they took care of my children, so whenever there is a need, my family members always help me.” Line 263, P4SuAs

“They told me to be calm and relaxed and not to worry about anything. They told me that I can tell them if I have any issues. They told me not to worry much and go to work calmly. They just told me to take precautions.” Line 389, P10AlRS

In summary, the family was found to provide emotional support. Their encouragement and support positively impacted the HCWs.

-

(ii)

Spousal support: Active agent in providing emotional support

The spouse was an active agent in providing emotional support to the HCWs to share experiences, fears, and emotions. Emotional upheaval during the crisis situation was shared with the partner. The partners encouraged, supported, and helped the HCWs to deal with the crisis situation. In some cases, the sharing of household responsibilities was reported, where the partner of the HCW took on more household responsibilities.

“I was staying alone here at that time, so he asked what happened. I said, I doubted that I had some problem. So he asked me what happened. So, I told him I couldn’t hold my breath for more than 10 s, so maybe I got CORONA…(laughing). He asked me about my problem… He said, ‘At this 1’O’ clock you are calling, you surely have some problem. But not Corona (Both laughing), go and consult a doctor.’ So that’s how he is positively supporting me.” Line 123, P22ViBA

“Personally, I’m not able to go to any functions, and I’m not able to be with my children because we are in a separate rooms due to COVID-19 duty. My husband helps me in managing the household and children. My children know what Corona is, and they know the advantages of being separate, and they aren’t stubborn.” Line 38, P4SuAs

“Yes, I’ll discuss with my wife, and she is from the same profession, but she is not on duty for one year because of having a child. She understands me well in this situation. She is on leave for one year, so she will not let my morale go down because she thinks like a health professional and supports me in this situation.” Line 180, P9ViRa

In summary, the spouse acted as a crucial agent in providing emotional support to the HCW. Along with emotional support, they also provided support in managing household chores.

-

(iii)

Support provided by leaders

Superiors who provided knowledge, shared experiences, provided guidance, listened to the HCWs’ concerns, and empathized with them were seen as supportive leaders on the work front. Supportive superiors were found to listen to the HCWs’ fears and educate them in the preventive measures that needed to be taken. They encouraged and understood the problems that the HCWs were facing while serving the patients.

“The main thing is our Sir Dr. S is very supportive—he made us feel less scared and my in-charge he keeps telling us again and again about safety measures and precautions we have to take.” Line 22, P4SVS

“Sometimes, I would feel tired. But my Sir was very supportive. I could tell him that I was feeling tired, and he would help me. He would always inquire about us, so I felt supported.” Line 240, P15ViSh

“They’ve taught me how to wear PPE kit properly and assisted me in giving proper treatment to the patient… I had fear, but my seniors helped me a lot in understanding the situation. We do have difficulties wearing gloves for a long time and applying sanitizers because it may harm our skin.” Line 80, P4ViSu

“In the beginning, I had a lot of fear, but Sir encouraged me and guided me on how to deal with COVID patients, and he instilled in me confidence.” Line 60, P1SVS

In short, the HCWs sought support from their superiors for information, encouragement and support for patient care, and professional advice.

-

(iv)

Support from co-workers: shared experiences

Co-workers at the workplace were also seen as potential social support. Along with gaining technical support from their co-workers, sharing experiences helped the HCWs deal with the situation. The HCWs thought of their colleagues like friends and family who supported each other in a crisis situation. Their interactions were mainly focused on sharing experiences, providing emotional and informational support, and helping each other by sharing duties such as working extra shifts. The participants reported that this helped them deal with critical situations at work and in their personal life. This made it easy for the HCWs to continue to work in this demanding situation.

“Actually, when we speak to our companions, we get much psychological support from them. If we share with them about one issue, they will theirs. Then together, we find solutions to our problems.” Line 401, P16ViDL

“I have a colleague here…he is like a big brother to me….I will share everything with him…everything…I ask for his suggestions if I am in a critical situation and what steps should to be taken to overcome it…” Line 153, P2AlAK

“I am glad to receive constant support and care from friends, colleagues and family members. They show great concern about my safety. Also, they encourage me to work by not compromising, taking all the precautionary measures.” Line 82, P1SVS

Briefly put, the HCWs gained technical knowledge and shared their experiences with their colleagues while working during the COVID-19 pandemic. This helped the HCWs in sharing their burden and duties.

B. Perceived need for support during the pandemic

-

(iv)

Need for psychological support

The participants reported the need for psychological support from mental health professionals. They suggested that even with support from family and friends, there is a need for professional guidance and a need to learn coping strategies to deal with the current situation effectively. The HCWs indicated that everyone was stressed and had little control over their work.

“Yes, sometimes I feel that we need to discuss with mental health professionals rather than discussing with our family members because mental health professionals will arrive at some strategies which will help us to cope with the situation better.” Line 172, P9ViRa

“They can conduct counseling sessions or something similar, especially for to those who are staying with their family and aged people. Their professional work will affect their personal life. Yes, counseling sessions should be conducted here…. for all who are interested in them they must conduct.” Line 443, P12ViVg

“There is no need of discussing - everybody is much stressed, so the administration itself has to arrange counseling sessions for all the staff to boost up their mental health.” Line 216, P17ViFa

“We can’t say how they should reduce their workload because they will be the only earning members of their family, so the only thing we can do is listen to their feelings.” Line 309, P4SuAs

Increasing stress levels on the professional impacting the personal lives of the HCWs; hence, they reported the need for professional support and guidance.

-

(ii)

Need for security, resources, financial and informational support

The HCWs recognized the strain the pandemic had caused on the healthcare system. They emphasized the need for the government to focus on the health and infrastructure budgets. The poor doctor-patient ratio had burdened the HCWs serving in the pandemic. A majority of the participants highlighted the need for basic necessities such as protective gear, food, and water. The HCWs reported that the government and hospital management need to recruit more staff to deal with the current crisis.

“One thing is …as I have understood is, patient load and doctors aren’t in reasonable ratio. …Health infrastructure and facilities are not good…. Nothing personal, but this is what I have concluded. I want the government to include health and infrastructure in the budget.” Line 185, P9AlUK