Abstract

Alan Rugman and co-authors argue that globalisation, and with it global strategy, is a myth. This contention rests on a taxonomy of the world's largest firms based on their sales, showing an overwhelming share of home-regional firms. We question the rationales underpinning their classification scheme. When retesting the data using different schema we find that the original results are far from robust, with a significant share of firms attaining bi-regional or global status. Further longitudinal analysis shows that large firms increasingly are extending their sales beyond the home region. Our results defy regionalisation theory in its current form, and we call for refinements through further research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Strictly speaking, if the broad triad accounts for roughly 90% of world output, a perfectly balanced global presence would require 30% in each triad market rather than 33.33%.

Accounting conventions give firms considerable leeway in how to report the geographic breakdown of their sales, and firms rarely follow the exact triad scheme. As a result, this entire research stream is affected by a significant level of “noise” in the data used. See Rugman (2005: Chapter 2) for a comprehensive disclosure and a discussion of the inevitable limitations that arise from relying on sales data as reported in company accounts.

Setting a threshold for the share of home region ex domestic sales is an obvious solution, but complicated by the fact that the “rest of home region” varies with the company's country of origin. For instance, the size of the “rest of home region” differs markedly for a US firm compared with a Canadian firm. Approaches that account for the relative GDP of the home country (e.g., Asmussen, 2006) seem to hold great promise in this regard.

Not only sales but also profits may be highly skewed across triad regions. For instance, it is well known that most big pharmaceutical companies, many of which feature in the Fortune Global 500, make about half of their profits in the US alone (Economist, 2007).

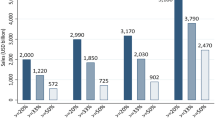

On the suggestion of a reviewer we set out to count the number of firms with host-region sales greater than US$1 billion. Sufficient data to perform this analysis was available for only 219 firms in Rugman's 365-strong sample. Of those 219 firms, 97 had sales greater than US$1 billion in both host regions, while 35 had attained such levels in one host region. The corresponding figures were 58 and 61 firms when the bar was raised to US$2 billion.

Clearly, such a simple scheme does not address our concerns regarding the inclusion of domestic sales among home-region sales. More complex classification systems may explicitly set thresholds for home-region sales ex domestic sales (weighted for the size of the home country within the home region).

Once the 50% threshold for home-region membership is removed, it becomes difficult to manage and rationalise the 50% benchmark for the special host-regional category. While it is a far from ideal categorisation, host-regional status now belongs only to those firms that achieve a market share greater than 20% in a host region and less than 20% in the home region. Most of the firms in the host-regional category tend to collapse into the bi-regional (and occasionally the global) category in subsequent tables.

Data insufficiencies bias this classification against finding global competitors, since Rugman's data contains numerous firms with no available information for a particular region (mostly Asia) and/or reported sales that make up significantly less than the 90% of total sales expected for the entire triad. For example, in 2001, pharmaceutical giant Glaxo reported European sales and US sales at 28.6 and 49.2% of total sales, respectively, rendering it a bi-regional in Rugman's classification scheme. Where the remaining 22.2% of sales took place was not disclosed by the company. It is likely that Glaxo's Asian sales during that year exceeded the 10% threshold, which would make the firm a global player according to one of our classification regimes.

Rugman (2005) does provide rudimentary temporal sensitivity analysis of his classification. For that purpose, he utilises updated 2002 figures for 60 firms in his original 2001 sample. Not surprisingly, a single year after the original analysis, “only two of these sixty firms were re-categorised” (2005: 32). This hardly constitutes a strong test of robustness over time.

We are cautiously confident about the representativeness of our sample. χ 2-tests of Rugman's original sample and our own, based on firms' region of origin and their distribution across the four categories in 2001 (using Rugman's classification scheme), were non-significant at the 1% level.

See Osegowitsch and Sammartino (2007) for a more detailed investigation of these trends, but see also Rugman and Oh (2007).

The definition of thresholds to distinguish global from bi-regional and home-regional firms is likely to remain a contentious issue unless the community of IB researchers can reach consensus as to what constitutes “significant” sales that warrant a particular categorisation. We note in passing that there is also disagreement whether sales should be the relevant criterion (see Aharoni, 2006; Rugman & Verbeke, 2004a: 7). Clearly, such a situation is far from unique. After all, IB scholars are still debating exactly what constitutes a multinational firm (Aharoni, 1971; Ghoshal & Westney, 1993).

The notion of FSA country or region boundedness implies an exogenous phenomenon, determined entirely by environmental forces. We view the boundaries of effective FSA leverage as also governed by firm-specific aspects and as partly controlled by management. As a result we prefer the term “FSA reach”.

The “Penrose effect” simply suggests that there are strict limits to a firm's growth rate due to dynamic adjustment costs that are incurred by firms trying to grow their productive resources. Penrose (1959) focused on one major source of dynamic adjustment costs, namely those attributable to the expansion of management resources. She insists that a firm's expansion requires the services of experienced internal managers. Hiring new managers is an inadequate solution, since only seasoned internal managers can undertake the coordination task inherent in firm expansion. As a result, the rate of growth is limited by the rate at which the firm can develop internal managers. Not only domestic expansion but also international expansion is subject to the Penrose effect (Tan & Mahoney, 2005).

We agree that firms typically begin their internationalisation in the home region. The home region is likely to contain some of the most similar (i.e., “least distant”) countries. FSA deployment in these initial destinations is facilitated by institutional similarities, cultural affiliations, lower transportation costs, etc. Beyond the initial round of internationalisation, market choices are likely to be much less focused on the home region, as similar countries also exist in other regions.

Based on evidence presented elsewhere (Osegowitsch & Sammartino, 2007), we also dismiss the possibility that firms venture into host regions only once they have exhausted growth opportunities in the home region, as a kind of “last resort” option to keep growing. Instead, it seems that many firms are simultaneously deploying their FSAs within and beyond the home region.

See also Aharoni (2006) and Westney (2006) on this point.

Hejazi (2007) is, to our knowledge, the only study trying to model a regional LOF in terms of MNE sales (as well as asset, income and employment) distribution. His methodology explicitly tries to disentangle country and regional effects. While the results must be treated as strictly preliminary, they do suggest that “distance” (as well as size differentials) between individual countries explains the sales distribution of US MNEs; regional (dummy) variables yield no additional explanatory power.

References

Aharoni, Y. 1971. On the definition of a multinational corporation. Quarterly Review of Economics and Business, 11 (3): 27–37.

Aharoni, Y. 2006. Book review: Alan M. Rugman, The regional multinationals. MNEs and global strategic management. International Business Review, 15 (4): 439–446.

Asmussen, C. G. 2006. Local, regional or global? Quantifying MNC geographic scope. SMG Working Paper 14/2006, Centre for Strategic Management and Globalization, Copenhagen Business School.

Bartlett, C. A., & Ghoshal, S. 1989. Managing across borders: The transnational solution. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Benito, G. R. J., & Gripsrud, G. 1992. The expansion of foreign direct investments: Discrete location choices or a cultural learning process? Journal of International Business Studies, 23 (3): 461–476.

Cembureau 2007. 2005 World cement production by region. http://www.cembureau.be/Documents/KeyFacts/STATISTICS/World%20Cement%20Production%20by%20Region.pdf. Accessed 24 March 2007.

Collinson, S. C. & Rugman, A. M. 2008. The regional nature of Japanese multinational business. Journal of International Business Studies, 39 (2): 215–230.

Dunning, J. H., Fujita, M., & Yakova, N. 2007. Some macro-data on the regionalisation/globalisation debate: A comment on the Rugman/Verbeke analysis. Journal of International Business Studies, 38 (1): 177–199.

Economist 1997. One world?. 18 October: 79–81.

Economist 2007. Billion dollar pills. 25 January: 61–64.

Enright, M. 2005. Regional management centers in the Asia-Pacific. Management International Review, 45 (Special Issue 1): 59–82.

Euromonitor 2000. Pharmaceuticals: A world survey. World market overview. Global Report, 2 June, Global Market Information Database. https://www.euromonitor.com/. Accessed 3 January 2007.

Euromonitor 2005. The world market for dairy products. Global Report, 7 June, Global Market Information Database. https://www.euromonitor.com/. Accessed 3 January 2007.

Ghemawat, P. 2001. Distance still matters. Harvard Business Review, 79 (8): 137–147.

Ghemawat, P. 2003. Semiglobalization and international business strategy. Journal of International Business Studies, 34 (2): 138–152.

Ghoshal, S., & Bartlett, C. A. 1990. The multinational corporation as an interorganizational network. Academy of Management Review, 15 (4): 603–625.

Ghoshal, S., & Westney, D. E. 1993. Introduction and overview. In S. Ghoshal and D. E. Westney (eds), Organization theory and the multinational corporation: 1–23. New York: St Martin's Press.

Hejazi, W. 2007. Reconsidering the concentration of US MNE activity: Is it global, regional or national? Management International Review, 47 (1): 5–27.

Johanson, J., & Wiedersheim-Paul, F. 1975. The internationalization of the firm: Four Swedish cases. Journal of Management Studies, 12 (3): 305–322.

Nokia 2003. Nokia in 2002. http://www.nokia.com/A4126499. Accessed 28 March 2007.

Ohmae, K. 1985. Triad power: The coming shape of global competition. New York: The Free Press.

Osegowitsch, T., & Sammartino, A. 2007. Exploring trends in regionalisation. In A. M. Rugman (ed.), Research in global strategic management, vol. 13, Regional aspects of multinationality and performance. Amsterdam: Elsevier: 45–64.

Penrose, E. T. 1959. The theory of the growth of the firm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rugman, A. M. 2000. The end of globalization. London: Random House.

Rugman, A. M. 2005. The regional multinationals: MNEs and “global” strategic management. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Rugman, A. M., & Brain, C. 2003. Multinational enterprises are regional, not global. Multinational Business Review, 11 (1): 3–12.

Rugman, A. M., & Hodgetts, R. M. 2001. The end of global strategy. European Management Journal, 19 (4): 333–343.

Rugman, A. M., & Oh, C. H. 2007. Multinationality and regional performance, 2001–2005. In A. M. Rugman (ed.), Research in global strategic management, vol. 13, Regional aspects of multinationality and performance. Amsterdam: Elsevier: 31–43.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. 1992. A note on the transnational solution and the transaction cost theory of multinational strategic management. Journal of International Business Studies, 23 (4): 761–771.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. 2004a. A perspective on regional and global strategies of multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 35 (1): 3–18.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. 2004b. Regional transnationals and triad strategy. Transnational Corporations, 13 (3): 1–19.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. 2005. Towards a theory of regional multinationals: A transaction cost economics approach. Management International Review, 45 (Special Issue 1): 5–17.

Rugman, A. M., & Verbeke, A. 2007. Liabilities of regional foreignness and the use of firm-level versus country-level data: A response to Dunning et al. Journal of International Business Studies, 38 (1): 200–205.

Tan, D., & Mahoney, J. T. 2005. Examining the Penrose effect in an international business context: The dynamics of Japanese firm growth in US industries. Managerial and Decision Economics, 26 (2): 113–127.

Teece, D. J. 1986. Profiting from technological innovation. Research Policy, 15 (6): 285–305.

Westney, E. 2006. Book review: The regional multinationals: MNEs and “global” strategic management. Journal of International Business Studies, 37 (3): 445–449.

Yip, G., Rugman, A. M., & Kudina, A. 2006. International success of British companies. Long Range Planning, 39 (3): 241–264.

Zaheer, S. 1995. Overcoming the liability of foreignness. Academy of Management Journal, 38 (2): 341–363.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Eric Quintane in compiling the data used in this paper. We also thank Editor-in-Chief Professor Arie Lewin and two anonymous JIBS reviewers for their efforts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Accepted by Arie Y Lewin, Editor-in-Chief, 18 June 2007. This paper has been with the authors for two revisions.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osegowitsch, T., Sammartino, A. Reassessing (home-)regionalisation. J Int Bus Stud 39, 184–196 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400345

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400345