Abstract

This paper examines the global distribution of current accounts. Using a panel of more than 100 countries, the analysis establishes a set of stylized facts regarding the collective behavior of current accounts over the past four decades. In particular, we find that the global dispersion of current accounts has been steadily rising, which is qualitatively consistent with the view that ongoing financial globalization has allowed countries to maintain larger current account imbalances. However, this underlying trend is not quantitatively large enough to explain “global imbalances”—that is, the noticeable widening in external imbalances among major economies (for example, United States) seen in recent years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Remarks at the 21st annual monetary conference at the Cato Institute, November 2003.

For recent studies on financial globalization, see Prasad and others (2003), Kose and others (2006), and the references cited therein.

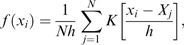

The kernel estimator for an arbitrary point x i in the distribution is:

where X j is the jth data observation, N is the number of observations, h is the window size (that is, the degree of smoothing), and K is the kernel or weighting function. The nonparametric estimates in Figure 1 are based on the Epanechhnikov kernel (see Silverman, 1986). Results using the less efficient Gaussian kernel (that is, standard normal) are very similar.

Jarque-Bera tests strongly reject normality for each of these years. Skewness in the distribution was found significant for each of these years, except 1960; excess kurtosis (that is, “fat tails”) was statistically significant throughout.

In contrast to the rising dispersion in the distribution of the current account as a share of GDP, the distribution of the ratio of the current account to trade (imports and exports) has remained stable over the years. In other words, current account positions (largely net trade balances or exports minus imports) have expanded globally at a rate on par with gross trade (exports plus imports) associated with the well-known expansion in world trade as a share of world GDP.

The global current account discrepancy—usually expressed in dollar terms or in percent of world imports or GDP—has mostly been negative since the early 1970s, reflecting discrepancies in both trade and income accounts; see Marquez and Workman (2001) for a discussion.

A regression of the (log) standard deviation on a time trend yields the following results (with corrected standard errors given in parentheses): ln(σCA/ GDP )=1.4+0.017t+ɛ t ; R2=0.33.

Over the sample, the rate of increasing global dispersion is 1½ to 1¾ percent per year on an unweighted basis and 3¼ percent on a weighted basis.

A weaker form of convergence posits that current accounts, but not trade balances nor net foreign asset positions, converge toward balance. This would require that trade (not current account) surpluses be achieved in the years following current account deficits to stabilize the accumulation of net foreign liabilities. Net foreign assets data are based on Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2001, 2007).

Reflecting limitations on historical data for net foreign assets, the cross-section consists of 94 countries. Similar positive-sloped regression results follow when the sample is split into surplus and deficit countries, as well as between high vs. low deficit countries. Chinn and Prasad (2003) find a similar effect of net foreign assets on current accounts based on multivariate panel estimation that controls for a wide range of explanatory variables (for example, demographics, fiscal positions, economic development, and so on).

Dropping outlier countries with average current account imbalances (net external assets) greater than 10 percent (50 percent) of GDP in absolute terms would slightly lower the coefficient on initial NFA (to 0.06) but raise its significance level (p-value=3 percent).

Trehan and Walsh showed that the stationarity of the current account was the necessary and sufficient condition, but the necessity was debated lately by Bohn (2005).

In all cases, the model specification includes a constant but no time trend. Including a time trend in the unit root tests marginally increase the number of rejections.

See Campbell and Perron (1991). A peculiar finding is that for three countries, these low-powered tests rejected both stationarity and nonstationarity for at least one unit root test.

Current account adding-up would be more apparent if balances were defined in a common unit (say) U.S. dollars—but this would raise issues of nominal drift. Using the current account ratio to GDP broadly preserves the level of the current account discrepancy (in percent of GDP) provided that surplus and deficit countries (as respective groups) are of similar economic size.

Owing to the unbalanced panel, the sign-preserving trend coefficient in (4) is estimated for the vast majority (but not all) countries. Including the full sample (which has countries with only few observations at the end of sample) would reduce the coefficient estimate given the accumulated value of the trend term itself. A “resetting” trend for these countries would raise the point estimate. For further sensitivity analysis, see the following footnote.

When the sign-preserving trend is constructed using the contemporaneous rather than lagged current account, the trend coefficient is always substantially larger and highly significant; and the AR1 coefficient is also substantially reduced. But this specification is susceptible to simultaneity issues. Across various specifications and samples, the range of trend estimates is roughly between 0.005 to 0.008. As a cross-check, the fitted values and implied rate of increase in global dispersion for a given trend estimate are compared to the rates from the nonparametric estimates discussed earlier.

In a deterministic setup, the ratio of the current account to GDP has a well-defined relationship to the steady-state ratio of NFA to GDP. In a stochastic setting, stationary shocks to the current account (changes in NFA) will have a nonstationary effect on NFA, and the stochastic steady-state relationship between the current account and NFA remains unclear.

See Ghironi, Lee, and Rebucci (2007) for further discussion of these costs and their role in determining the steady-state values of the NFA-to-GDP ratio.

References

Blanchard, Olivier J., and Francesco Giavazzi, 2002, “Current Account Deficits in the Euro Area. The End of the Feldstein Horioka Puzzle?,” in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: 2, ed. by George L. Perry (Washington, The Brookings Institution), pp. 147–209.

Blanchard, Olivier J., and Filipa Sa, 2005, “International Investors, the U.S. Current Account, and the Dollar,” in Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: 1, ed. by William C. Brainard (Washington, The Brookings Institution), pp. 1–65.

Bohn, Henning, 2005, “Are Stationarity and Cointegration Restrictions Necessary for the Intertemporal Budget Constraint?” (unpublished; California, University of California at Santa Barbara).

Breitung, Jorg, 2000, “The Local Power of Some Unit Root Tests for Panel Data,” in Advances in Econometrics, Vol. 15: Nonstationary Panels, Panel Cointegration, and Dynamic Panels, ed. by B. Baltagi (Amsterdam, JAI Press), pp. 161–178.

Campbell, John Y., and Pierre Perron, 1991, “Pitfalls and Opportunities: What Macroeconomists Should Know about Unit Roots,” in NBER Macroeconomics Annual 1991, ed. Oliver J. Blanchard and Stanley Fischer (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research), pp. 141–219.

Chinn, Menzie D., and Eswar Prasad, 2003, “Medium Term Determinants of Current Accounts in Industrial and Developing Countries: An Empirical Exploration,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 47–76.

Chinn, Menzie D., and Hiro Ito, 2006, “What Matters for Financial Development? Capital Controls, Institutions, and Interactions,” Journal of Development Economics, Vol. 61, No. 1, pp. 163–192.

Chinn, Menzie D., and Jaewoo Lee, 2009, “Three Current Account Balances: A Semi-Structuralist Interpretation,” Japan and the World Economy, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 201–212.

Faruqee, H., D. Laxton, D. Muir, and P. Pesenti, 2006a, “Smooth Landing or Crash? Model-based Scenarios of Global Current Account Rebalancing,” in G-7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment, National Bureau of Economic Research conference volume, ed. by R. Clarida (Chicago, University of Chicago Press).

Faruqee, H., D. Laxton, D. Muir, and P. Pesenti, 2006b, “Would Protectionism Defuse Global Imbalances and Spur Economic Activity? A Scenario Analysis,” NBER Working Paper 12704 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Feldstein, Martin, and Charles Horioka, 1980, “Domestic Saving and International Capital Flows,” Economic Journal, Vol. 90, pp. 14–29.

Ghironi, Fabio, Jaewoo Lee, and Alessandro Rebucci, 2007, “The Valuation Channel of External Adjustment,” NBER Working Paper 12937 (Cambridge, Massachusetts, National Bureau of Economic Research).

Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, and Helene Rey, 2005, “From World Banker to World Venture Capitalist: The U.S. External Adjustment and the Exorbitant Privilege,” in G-7 Current Account Imbalances: Sustainability and Adjustment, National Bureau of Economic Research conference volume, ed. by R. Clarida (Chicago, University of Chicago Press).

Greenspan, Alan, 2003, “Current Account,” Presentation at the 21st Annual Monetary Conference, cosponsored by the Cato Institute and The Economist, Washington. Available via the Internet: www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2003/20031120/default.htm.

Im, Kyung, Hashem Pesaran, and Yongcheol Shin, 2003, “Testing for Unit Roots in Heterogeneous Panels,” Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 115, pp. 53–74.

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2005, World Economic Outlook, World Economic and Financial Surveys (Washington, September).

Kose, M. Ayhan, Christopher Otrok, and Eswar S. Prasad, 2008, “Global Business Cycles: Convergence or Decoupling?” IMF Working Paper 08/143 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Kose, M. Ayhan, Eswar S. Prasad, Kenneth Rogoff, and Shang-Jin Wei, 2006, “Financial Globalization: A Reappraisal,” IMF Working Paper 06/189 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Kraay, Art, and Jaume Ventura, 2000, “Current Accounts in Debtor and Creditor Countries,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 115, No. 4, pp. 1137–1166.

Kwiatkowski, Denis, Peter C.B. Phillips, Peter Schmidt, and Yongcheol Shin, 1992, “Testing the Null Hypothesis of Stationary against the Alternative of a Unit Root,” Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 54, pp. 159–178.

Lane, Philip, and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, 2001, “The External Wealth of Nations: Measures of Foreign Assets and Liabilities in Industrial and Developing Countries,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 55, No. 2, pp. 263–294.

Lane, Philip, and Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti, 2007, “The External Wealth of Nations Mark II: Revised and Extended Estimates of Foreign Assets and Liabilities,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 223–250.

Levin, Andrew, Chien-Fu Lin, and Shia-Shang Chu, 2002, “Unit Root Tests in Panel Data: Asymptotic and Finite-Sample Properties,” Journal of Econometrics, Vol. 108, pp. 1–24.

Marquez, Jaime, and Lisa Workman, 2001, “Modeling the IMF's Statistical Discrepancy in the Global Current Account,” Staff Papers, International Monetary Fund, Vol. 48, No. 3, pp. 499–521.

Prasad, Eswar S., Kenneth Rogoff, Shang-Jin Wei, and M. Ayhan Kose, 2003, “Effects of Financial Globalization on Developing Countries: Some Empirical Evidence,” IMF Occasional Paper No. 220 (Washington, International Monetary Fund).

Silverman, Bernard W., 1986, Density Estimation for Statistics and Data Analysis (London, Chapman and Hall).

Taylor, Alan, 2002, “A Century of Current Account Dynamics,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 21, No. 6, pp. 725–748.

Trehan, Bharat, and Carl E. Walsh, 1991, “Testing Intertemporal Budget Constraints: Theory and Application to U.S. Federal Budget and Current Account Deficits,” Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 206–223.

Additional information

*Hamid Faruqee is assistant to the director of the IMF Research Department. Jaewoo Lee is deputy division chief of the Open-Economy Macroeconomics Division of the IMF Research Department. The authors appreciate comments by Menzie Chinn, Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas, Hiro Ito, Kwanho Shin, and participants in the 2006 AEA meeting, the Bank of Korea, and the May 2008 conference in the University of Wisconsin, Current Account Sustainability in Major Advanced Economies II. Liudmyla Hvozdyk provided very helpful research assistance.

Appendices

Appendix I: Data Description

The main variable is the ratio of the current account to the GDP, both of which were obtained from various issues of International Financial Statistics (IMF) and World Development Indicators (World Bank). The capital account liberalization index was developed by Chinn and Ito (2006), and is the first principal component of several variables that reflect the ease of cross-border financial transactions. In our estimation, the index was normalized to take a value between 0 and 1, increasing with the liberalization of capital account regime. For each value of Chinn-Ito index CI it , our indicator is defined as follows:

Appendix II: Alternative Measures of External Positions and Their Behavior

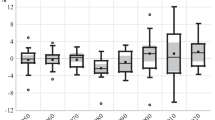

A related but distinct measure is the change in net foreign assets (NFA). It essentially differs from the current account by the amount of capital gains (valuation change), which is driven by asset price fluctuations, including exchange rate variations. Because these asset price movements are broadly described as a random walk, the change in NFA will contain a much larger white-noise component and exhibit smaller persistence than the current account. This is indeed confirmed by the data, as summarized in the following two charts. Note that due to data limitations regarding NFA, the sample size is smaller.

First, the change in NFA (in percent of GDP) is subjected to the same battery of stationarity and unit root tests as for the current account, summarized in Figure 4. The test results uniformly show a higher rejection rate of nonstationarity. See Figure A1. Second, for the change in the ratio of NFA to GDP—that is, (NFA/y)— the indications toward stationarity are even stronger; see Figure A2. Changes in the ratio also include a growth term (related to the change in the scaling variable GDP). This helps toward finding stationarity in the ratio given that GDP (that is, the denominator) is growing over time. Excluding the growth factor term (by considering NFA/y) weakens the stationarity finding, but does not overturn it. That is, the NFA concept appears to be much more stationary (less persistent) series than the current account.