Abstract

The paper examines the determinants of cross-border interbank and intragroup funding across crisis and noncrisis periods. Using a previously unexplored data set spanning 25 banking systems, it finds that aggregate intragroup funding is unrelated to fluctuations in either global or local macroeconomic fluctuations, while flightier interbank funding responds procyclically to both worldwide and domestic economic trends. This feature of the data means intragroup funding remains comparatively stable when global conditions deteriorate—even during the global financial crisis. During “normal” times the paper finds that intragroup funding responds countercyclically to global interest rate changes, with parent banks using affiliates to offset tighter global funding conditions. More generally, it finds that intragroup funding has a closer relationship with domestic banking system profitability and solvency, being used to support banks in weaker banking systems during the global financial crisis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

One study to also directly investigate intragroup flows across multiple countries is by Allen, Gu, and Kowalewski (2013). The authors hand-collect data on intragroup transactions from the financial statements of European Union banks between 2007 and 2009. The main purpose of this study, however, is to evaluate the European Union’s regulatory structure regarding internal capital market flows and evaluate its appropriateness in light of the transactions uncovered within the study. The main finding is that intragroup transactions could be significantly detrimental to a foreign affiliate to the extent that a country’s financial stability could be affected.

The results of our paper indicate that a fruitful area for future theoretical and empirical work could explore why global banks adopt one type of cross-border funding structure over another and whether a possible optimal combination exists that maximizes firm value. Kerl and Niepmann (2014) make a recent theoretical contribution in this direction, finding that a bank’s composition of interbank relative to intragroup lending is driven by the efficiency of the banking system, the return to capital and entry barriers which impede foreign bank operations. From an empirical perspective, De Haas and Kirschenmann (2013) investigate the determinants of internal capital market characteristics. Interviewing the CEOs of over 400 banks from emerging Europe, the authors find parent- and host-country characteristics are stronger determinants of the intragroup structure than either parent or foreign affiliate bank characteristics.

See Goldberg and Gupta (2013) and Carney (2013) for recent discussions and the Federal Reserve Board (2014) for a description of the recently finalized rules that require large foreign affiliates operating in the United States to adhere to U.S. capital and liquidity rules.

Although the BIS makes some international banking data publicly available, due to confidentiality, the split between interbank and intragroup funding is part of a nonpublic restricted data set.

While we exclude offshore banking centers, note that the funding from offshore banking centers to the 25 banking systems in our study is included. We choose not to study the funding to offshore banking centers for three reasons. First, our primary interest is the impact cross-border flows may have on domestic financial stability, independent of whether these flows were intermediated by offshore centers. Second, only sparse interbank and intragroup data are available for offshore centers. Specifically, only the Cayman Islands, Macao, Panama, and Bermuda report such data, while there are no data for Hong Kong, Singapore, Guernsey, or Jersey. Third, in our empirical setup, we choose to control for country and banking system characteristics. These data are only sparsely available for offshore banking systems, particularly for the few offshore centers which report data on the split between interbank and intragroup funding. Note also, that apart from excluding countries which do not report both interbank and intragroup flow data, we also exclude Finland as it only reports intragroup flows from 2010:Q2 onward.

Owing to data confidentiality, we are unable to report specific country details on intragroup funding and hence, for the purposes of the figure, we anonymize countries.

The countries k=26, 27, …, K do not report banking statistics to the BIS but have resident global banks with operations abroad (significant examples include China and Russia).

The numbers reflect the median change in interbank and intragroup funding across all 25 banking systems in the study. To calculate the change, we sum across flows (adjusted for exchange rate fluctuations) and divide by the stock of funding at the start of the crisis.

More precisely, we measure realized volatility as the square-root of average squared daily returns to the MSCI Global Equity Index, a composite measure of returns across 23 developed market stock indices.

It is not known, however, if flows to a foreign affiliate are directly from the parent bank or from another foreign affiliate located outside the country. The BIS is currently expanding its data set to include bilateral interbank and intragroup flows (Committee on the Global Financial System, 2012), which will help provide further details on the dynamics of internal capital market funding.

We estimate a Hausman test and find that the null hypothesis (the random-effects estimator is consistent) is strongly rejected, indicating the appropriateness of a fixed-effects model.

We examine the impact of two-way clustering in Section III.

The measure provides a broad empirical proxy of global economic uncertainty, providing a more precise measure of “global” uncertainty than the alternative U.S.-centric VIX index of implied U.S. stock market volatility.

Given the natural link between short-term money market rates and broad money growth, changes in interest rates may capture fluctuations in global liquidity which have been linked with bank runs (Giannetti, 2007) and changes in global bank leverage (Brunnermeier, 2009).

Parent banks may purposefully adopt a countercyclical intragroup funding strategy to offset, for example, monetary policy shocks (Jeon and Wu, 2014) or the negative liquidity shock associated with a credit rating downgrade (Karam and others, 2014). De Haas and Van Lelyveld (2014) find parent banks provided less support to their foreign affiliates during the GFC implying that intragroup funding may also contribute to the international propagation of financial shocks, while Popov and Udell (2012) find that foreign affiliates whose parents had low equity ratios or suffered large financial asset losses, reduced their domestic credit expansion by more during the GFC. Cetorelli and Goldberg (2012b) also find the business purpose of the foreign affiliate is important. Specifically, during the 2008–09 crisis, U.S. global banks reallocated intragroup funding back to the United States according to an organizational pecking order: traditional funding locations were used more actively to buffer the domestic liquidity shock, while foreign affiliates viewed as key revenue generators were largely shielded from providing liquidity support.

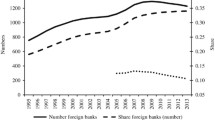

The figure is based on all foreign and domestic banks in an economy using data from Bankscope. Although Bankscope data are comprehensive, it does not take into consideration the return on equity of foreign branches.

De Haas and Van Horen (2013) also find that parent banks were more likely to maintain intragroup funding during the global financial crisis to affiliates in countries closest to the parent bank’s headquarters.

Note that while ROE and the net interest margin are both linked to performance and profitability, they are not by definition highly correlated. A banking system with a high average ROE, for example, may also be highly leveraged, which amplifies even a small net interest margin and hence the two findings are not incompatible. A possible concern associated with the high correlation between the net interest margin and solvency is that the estimated coefficients are distorted by multicollinearity. To mitigate this concern, we remove the net interest margin and find the ROE and solvency coefficients remain qualitatively unchanged. These additional results are not reported in the interest of space but are available on request.

Note that the study investigates individual banks rather than aggregate banking system data as is done in this study. Moreover, the study excludes foreign branches, whereas we include data on all affiliates, including both foreign subsidiaries as well as foreign branches.

The results presented in this section are also economically significant: a one standard deviation rise in the MSCI index of 0.43 reduces interbank funding growth by 1.52 percentage points (pp) (it rose by around 2 standard deviations following Lehman Brothers’ collapse); and a level of the MSCI index of 53 in 2008:Q3 implies 8pp lower interbank funding growth compared with the calmest periods in the sample. A tightening in global interest rates of 50 basis points reduces interbank funding growth by 2.6pp but increases intragroup funding growth by 2.2 percent. Finally, a one standard deviation rise of around 10pp in a banking system’s return on equity is associated with 1pp higher interbank funding growth and 1.7pp higher intragroup funding growth.

Specifically, in the second specification we remove the period from 2008:Q4 to 2009:Q2 to coincide with the large drop in cross-border bank-to-bank funding documented in Figure 2 that followed the collapse of Lehman Brothers. In the third specification, we remove the period from 2008:Q4 to the end of our sample in 2011:Q4.

The result supports a recent finding by Hoggarth, Hooley, and Korniyenko (2013), who show that gross cross-border intragroup lending by foreign affiliates, resident in the United Kingdom, increased strongly following the run on the British bank, Northern Rock. Notably, the result is driven by the intragroup lending of foreign branches. The gross lending by foreign subsidiaries remained unchanged.

Although not the focus of our paper, in Table A3 we present results on the behavior of interbank funding growth to parent and affiliate banks. Global factors matter for both sets of banks, but we find that global volatility and changes in global interest rates have a stronger impact on parent banks, whereas global growth seems to be the dominant driver of interbank funding to affiliates. We also find evidence that interbank funding to affiliates is more strongly associated with domestic macroeconomic cycles than parent funding, while the opposite is the case for the average profitability of the banking system as a whole.

Recent papers which use the VIX index as a measure of global risk include, inter alia, Longstaff and others (2011), Bacchetta and Van Wincoop (2013), Forbes and Warnock (2012a), and Fratzscher (2012).

Results for including fixed effects are similar but significant only at the 10 percent level. Because most instances of liquidity support occurred during the GFC, we think it is more instructive to also exploit the cross-sectional variation in the size of liquidity support. See Table A6 for further discussion on the effect of excluding fixed effects.

Our regressions account for the health of a country’s banking system. However, one important caveat of including liquidity support is that more liquidity support could be a measure of how intense the banking crisis had been, making it hard to estimate its overall effect. Definitive answers on the impact of liquidity support on interbank and intragroup funding are thus beyond the scope of this paper, most likely requiring micro-banking data such as in Drechsler and others (2014) to provider crisper answers.

As many countries started to report their data only later to the BIS, the sample starting from 1985:Q1 is less balanced than for baseline sample.

The covariance matrix was adjusted using the procedure proposed by Cameron, Gelbach, and Miller (2011).

We have also explored the robustness of our main results to increasing the level of winsorization to 5 percent and find that large observations do not drive any of the key results. We omit these results in the interest of space but they are available upon request.

References

Adrian, Tobias and Hyun Song Shin, 2010, “Liquidity and Leverage,” Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 418–37.

Allen, Franklin, Xian Gu, and Oskar Kowalewski, 2013, “Corporate Governance and Intra-Group Transaction in European Bank Holding Companies During the Crisis,” in Global Banking, Financial Markets and Crises (International Finance Review, Volume 14) ed. by Bang N. Jeon, and Maria P. Olivero (Bingley, UK: Emerald Group Publishing Limited), pp. 365–431.

Bacchetta, Philippe and Eric van Wincoop, 2013, “Sudden Spikes in Global Risk,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 89, No. 2, pp. 511–21.

Beck, Thorsten, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, and Ross Levine, 2000, “A New Database on the Structure and Development of the Financial Sector,” World Bank Economic Review, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 597–605.

Beck, Thorsten, Asli Demirgüç-Kunt, and Ross Levine, 2009, “Financial Institutions and Markets Across Countries and Over Time: Data and Analysis,” Policy Research Working Paper No. 4943 (The World Bank).

Brunnermeier, Markus K., 2009, “Deciphering the Liquidity and Credit Crunch 2007–2008,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 77–100.

Bruno, Valentina and Hyun Song Shin, 2015, “Cross-Border Banking and Global Liquidity,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 82, No. 2, pp. 535–64.

Calvo, Guillermo A., Leonardo Leiderman, and Carmen M. Reinhart, spring 1996, “Inflows of Capital to Developing Countries in the 1990s,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 10, No. 2 123–39.

Cameron, A. Colin, Jonah Gelbach, and Douglas Miller, 2011, “Robust Inference with Multi-way Clustering,” Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, Vol. 29, No. 2, pp. 238–49.

Cameron, A. Colin and Douglas Miller, 2015, “A Practitioner’s Guide to Cluster-Robust Inference,” Journal of Human Resources, Vol. 50, No. 2, pp. 317–73.

Carney, Mark, 2013, “Rebuilding Trust in Global Banking,” Speech presented at the 7th Annual Thomas d’Quino Lecture on Leadership, Lawrence National Centre for Policy and Management, Richard Ivey School of Business, Western University, London, Ontario, 25 February.

Cerutti, Eugenio and Stijn Claessens, 2013, “The Great Cross-Border Bank Deleveraging: Supply Side Characteristics,” mimeo, paper presented at joint workshop organized by the Paris School of Economics, Banque de France, Federal Reserve Bank of New York and CEPR on the “Economics of Cross-Border Banking” on December 14, 2013.

Cerutti, Eugenio, Stijn Claessens, and Lev Ratnovski, 2014, “Global Liquidity and Drivers of Cross-Border Bank Flows,” IMF Working Paper.

Cerutti, Eugenio, Anna Ilyina, Yulia Makarova, and Christian Schmieder, 2010, “Bankers Without Borders? Implications of Ring-Fencing for European Cross-Border Banks,” IMF Working Paper.

Cetorelli, Nicola and Linda S. Goldberg, 2011, “Global Banks and International Shock Transmission: Evidence from the Crisis,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 59, No. 1, pp. 41–76.

Cetorelli, Nicola and Linda S. Goldberg, 2012a, “Banking Globalization and Monetary Transmission,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 67, No. 5, pp. 1811–43.

Cetorelli, Nicola and Linda S. Goldberg, 2012b, “Liquidity Management of U.S. Global Banks: Internal Capital Markets in the Great Recession,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 88, No. 2, pp. 299–311.

Cetorelli, Nicola and Linda S. Goldberg, 2012c, “Follow the Money: Quantifying Domestic Effects of Foreign Bank Shocks in the Great Recession,” American Economic Review, Vol. 102, No. 3, pp. 213–18.

Claessens, Stijn and Neeltje van Horen, 2014, “Foreign Banks: Trends and Impact,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 295–326.

Committee on the Global Financial System. 2012, “Improving the BIS International Banking Statistics,” CGFS Papers, No. 47.

De Haas, Ralph and Karolin Kirschenmann, 2013, “Powerful Parents? The Local Impact of Banks’ Global Business Models” (unpublished manuscript; European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and Tilburg University).

De Haas, Ralph and Neeltje van Horen, 2013, “Running for the Exit? International Bank Lending During a Financial Crisis,” Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1, pp. 244–85.

De Haas, Ralph and Iman van Lelyveld, 2010, “Internal Capital Markets and Lending by Multinational Bank Subsidiaries,” Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 19, No. 1, pp. 1–25.

De Haas, Ralph and Iman van Lelyveld, 2014, “Multinational Banks and the Global Financial Crisis: Weathering the Perfect Storm?,” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 333–64.

Drechsler, Itmar, Thomas Drechsel, David Marques, and Philipp Schnabl, 2014, “Who Borrows from the Lender of Last Resort?,” Journal of Finance, mimeo.

Federal Reserve Board. 2014, “Enhanced Prudential Standards for Bank Holding Companies and Foreign Banking Organizations” [Press Release]. Available via the Internet: http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/bcreg/20140218a.htm (accessed 18 February 2014).

Forbes, Kristin J. and Francis E. Warnock, 2012a, “Capital Flow Waves: Surges, Stops, Flight, and Retrenchment,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 88, No. 2, pp. 235–51.

Forbes, Kristin J. and Francis E. Warnock, 2012b, “Debt- and Equity-Led Capital Flow Episodes,” Bank of Chile Working Papers No. 676.

Fratzscher, Marcel, 2012, “Capital Flows, Push Versus Pull Factors and the Global Financial Crisis,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 88, No. 2, pp. 341–56.

Giannetti, Mariassunta, 2007, “Financial Liberalization and Banking Crises: The Role of Capital Inflows and Lack of Transparency,” Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 32–63.

Goldberg, Linda and Arun Gupta, 2013, “Ring-Fencing and ‘Financial Protectionism’ in International Banking,” 9 January. Available via the Internet: www.libertystreeteconomics.newyorkfed.org.

Hassan, Tarek A. and Rui C. Mano, 2014, “Forward and Spot Exchange Rates in a Multi-currency World,” NBER Working Papers 20294.

Hattori, Masazumi and Hyun Song Shin, 2009, “Yen Carry Trade and the Subprime Crisis,” IMF Staff Papers 56, pp. 384–409.

Hoggarth, Glenn, John Hooley, and Yevgeniya Korniyenko, 2013, “Which Way do Foreign Branches Sway? Evidence from the Recent UK Domestic Credit Cycle,” Bank of England Financial Stability Paper 22.

Huang, Rocco and Lev Ratnovski, 2011, “The Dark Side of Bank Wholesale Funding,” Journal of Financial Intermediation, Vol. 20, No. 2, pp. 248–63.

Jeon, Bang N. and Ji Wu, 2014, “The Role of Foreign Banks in Monetary Policy Transmission: Evidence from Asia During the Crisis of 2008–9,” Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, Vol. 29, No. C, pp. 96–120.

Jeon, Bang N., Maria P. Olivero, and Ji Wu, 2013, “Multinational Banking and the International Transmission of Financial Shocks: Evidence from Foreign Bank Subsidiaries,” Journal of Banking and Finance, Vol. 37, No. 3, pp. 952–72.

Karam, Philippe, Ouarda Merrouche, Moez Souissi, and Rima Turk, 2014, “The Transmission of Liquidity Shocks: The Role of Internal Capital Markets and Bank Funding Strategies,” IMF Working Paper.

Kerl, Cornelia and Friederike Niepmann, 2014, What Determines the Composition of International Bank Flows? Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Report No. 681.

Laeven, Luc and Fabiain Valencia, 2013, “Systemic Banking Crises Database,” IMF Economic Review, Vol. 61, No. 2, pp. 225–70.

Longstaff, Francis A., Jun Pan, Lasse H. Pedersen, and Kenneth J. Singleton, 2011, “How Sovereign is Sovereign Credit Risk?,” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 75–103.

Lustig, Hanno, Nikolai Roussanov, and Arien Verdelhan, 2011, “Common Risk Factors in Currency Markets,” Review of Financial Studies, Vol. 24, No. 11, pp. 3731–77.

McCauley, Robert N., Patrick McGuire, and Goetz von Peter, 2010, BIS Quarterly Review(Basel: Bank for International Settlements Press).

Obstfeld, Maurice, 2012, “Does the Current Account Still Matter?,” American Economic Review, Vol. 102, No. 3, pp. 1–23.

Ongena, Steven, Jose-Luis Peydró, and Neeltje van Horen, 2013, “Shocks Abroad, Pain at Home? Bank-Firm Level Evidence on the International Transmission of Financial Shocks,” DNB Working Papers No. 385.

Popov, Alexander and Gregory F. Udell, 2012, “Cross-Border Banking, Credit Access, and the Financial Crisis,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 87, No. 1, pp. 147–61.

Rey, Helen, 2015, “Dilemma not Trilemma: The global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence,” NBER Working Paper No. 21162.

Schnabl, Philipp, 2012, “The International Transmission of Bank Liquidity Shocks: Evidence from an Emerging Market,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 67, No. 3, pp. 897–932.

Shirota, Toyoichiro, 2015, “What is the Major Determinant of Cross-Border Banking Flows?,” Journal of International Money and Finance, Vol. 53, No. C, pp. 137–47.

Stein, Jeremy C., 1997, “Internal Capital Markets and the Competition for Corporate Resources,” Journal of Finance, Vol. 52, No. 1, pp. 111–33.

Additional information

*Dennis Reinhardt is an Economist in the International Directorate of the Bank of England. He received his Ph.D. in Economics from the Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva. Steven Riddiough is at the Department of Finance of the University of Melbourne. He received his Ph.D. in Finance from the University of Warwick in 2014. His paper “Currency Premia and Global Imbalances” won the Kepos Capital Award for the Best Paper on Investments at the 2013 WFA Annual Meeting. The authors are grateful for comments and suggestions to Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas (Editor), two anonymous referees, David Barr, Martin Brooke, Charles Calomiris, Eugenio Cerutti, Pasquale Della Corte, Glenn Hoggarth, Iman van Lelyveld, Friederike Niepmann, Jonathan Newton, Katheryn Russ, Lucio Sarno, Filip Žikeš as well as seminar participants at the Bank of England, the ECB, the 2014 European Economic Association Annual Congress, the 2014 World Congress of the IEA and the DNB/IMF Conference on “International Banking: Microfoundations and Macroeconomic Implications.” They also thank Boris Butt and George Gale for excellent research assistance and David Osborn for answering many data-related questions.

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s41308-017-0034-4.

Electronic supplementary material

Appendix

Appendix

See Tables A1, A2, A3, A4, A5 and A6.