Abstract

This paper analyses the impact of type of insurance, income and reason for appointment on waiting time for an appointment and waiting time in the physician's practice in the outpatient sector. Data was obtained from a German patient survey conducted between 2007 and 2009. We differentiated between general practitioner (GP) and specialist and controlled for socioeconomic, structural and institutional characteristics as well as interactions between type of insurance and control variables. Our results reveal that private health insurance plays a significant role in faster access to care at GP and specialist practices. Access to care is also highly influenced by the reason for an appointment. We also found that increased income had a negative effect on waiting time in practices and on waiting time for an appointment in GP practices. Whether inequalities in access to health care also impact overall quality of treatment needs to be investigated in future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In several countries, health system objectives include the provision of equal access to health care for equal need. Disparities in access are assumed to negatively affect health outcomes due to delays in diagnosis and treatment and to generate dissatisfaction and uncertainty among patients.Footnote 1 Because waiting times for medical care are considered an implicit form of rationing within the health-care sector, they pose a serious health policy issue. Unlike through rationing by price, the loss of consumer welfare due to waiting times is not offset by any gain by the producer. The cost imposed on patients is thus a deadweight loss.Footnote 2

In previous studies, waiting time for elective surgery has often been considered as a measure for access to care.Footnote 3 Several studies provide evidence that waiting time for elective surgery is associated with socioeconomic characteristics, such as education, income or residence.Footnote 4 In addition, the type of insurance is considered as a relevant criterion for access to medical care.Footnote 5 Despite the importance of ensuring timely access to outpatient care, only a few studies have so far examined the determinants of access to outpatient care.Footnote 6

Germany, with its multi-payer health-care system, seems to be the ideal case to study the effect of type of insurance and income in the outpatient sector. The health insurance system in Germany is divided into two main components, statutory health insurance (SHI) and private health insurance (PHI). While SHI is financed by income-related contribution rates, PHI is financed by risk-based rates. Nearly 85.2 per cent of the German people are members of the SHI as compulsorily or voluntarily insured persons or as non-contributory family members. There is a dynamic income threshold (€49,500 for the year 2011), above which employees no longer are insured compulsorily. Above this threshold employees can either opt out to be a voluntary member of the SHI or opt out and take up PHI. Civil servants and self-employed persons have the choice between SHI and PHI without having to consider any threshold. Approximately 10.8 per cent of the population holds full PHI.Footnote 7

Differences in health care between persons with SHI and PHI may result from deviating reimbursement schemes. For outpatient care SHI reimburses physicians at lower rates (PHI reimbursement is 2.28 times the SHI reimbursement for the same serviceFootnote 8), imposes volume restrictions on the overall amount of services and has a less generous benefit package than PHI. Thus, the argument is made that differences in physician reimbursement rates create incentives for the preferential treatment of patients with PHI in the outpatient setting. SHI patients may face longer waiting times for outpatient appointments as well as longer waiting times in the doctors’ practice.Footnote 9 Therefore, an ongoing debate is taking place in Germany about the assumption that access to care differs between patients according to their insurance status.

In this study, we analysed the effect of type of insurance, income and reason for the appointment on waiting times in outpatient care controlling for other socioeconomic variables as well as for institutional characteristics in a large, representative sample of the German population from the Bertelsmann Health care Monitor. We measured waiting time as waiting time prior to an outpatient appointment with the general practitioner (GP) and specialist and waiting time in practices of the GPs and specialists.

Literature overview

There is a vast body of literature that analyses waiting times with respect to access to care and its determinants. However, so far studies mainly focused on waiting times for inpatient care, that is, for elective surgeries in general, organ transplantation or specific subgroups. Lofvendahl et al. Footnote 10 assessed the influence of socioeconomic variables, hospital type, health-related quality of life on waiting time for three groups of orthopaedic patients in Sweden and identified factors that explained variation in waiting time. Hospital-related factors were found to be more important than patient characteristics in explaining variations in waiting time for orthopaedic surgery.10 A study by Siciliani and VerzulliFootnote 11 used data of the Survey of Health, Ageing, and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). They analysed waiting time for specialist consultation and elective surgery.11 The authors found an increase in income of €10,000 reduced waiting time for specialist consultation by 8 per cent in Germany.

Schoen et al. Footnote 12 compared adults’ health-care experiences, including waiting time for elective surgeries in Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the United Kingdom and the United States. German and U.S. respondents reported the most rapid access while Canadian and British adults experienced the longest waits.12 In most countries, waiting time longer than one year was seldom; however, in Canada and the United Kingdom, 8 per cent reported waiting times of more than one year.

One of the latest studies on the topic of waiting times was authored by Johar et al. Footnote 13 They modelled waiting times for elective surgeries in public hospitals in Australia using administrative data. The results indicated that expectation of long waiting time does not increase the probability of purchasing PHI while experience of a long waiting time does.13

Few national and international studies exist that analyse the influence of type of insurance and waiting time. SchellhornFootnote 14 compared waiting time for an appointment with the GP or a specialist and waiting time in the practice of a GP and physician for PHI and SHI insured in Germany based on the patient survey of the Bertelsmann Health care Monitor. His results showed that there is no significant difference between different insurance types and waiting time for an appointment with the GP while there were significant differences in the waiting time in the GP office.14 Krobot et al. Footnote 15 revealed that disparities in access to innovative treatments and shorter waiting time persist across different types of insurance in Germany.15

Study results from the United States and the United Kingdom also revealed that shorter waiting times persist across different types of insurance. Dimakou et al. Footnote 16 showed that shorter waiting time for elective surgeries in England was mainly driven by supplementary PHI. Other characteristics such as age, sex and ethnicity showed no effect.16 Several studies compared waiting time for those insured under U.S. Medicaid and Medicare with private insurance plans and found shorter waiting times for privately insured.Footnote 17

Methods

We measured waiting time in two ways at practices of GPs (models Ia and Ib) and specialists (models IIa and IIb). Waiting time for an appointment was measured by the days patients, who had an outpatient contact in the previous 12 months, had to wait for an appointment with a GP or specialist. We interpreted waiting time for an appointment with the GP (model Ia) and with the specialist (model IIa) as an indicator of access to care.Footnote 18

Waiting time within the practice was assessed by the number of minutes patients had to wait until they were examined, treated or consulted by the physician. In this context it is important to note that usually no nurses are present in physician's practices in Germany. Thus, patients must see the physician in person to be examined, treated or consulted. We also interpreted waiting time in GP practices (model Ib) and in specialist practices (model IIb) as an indicator for access to care.

To avoid bias from miscoding and extreme outliers which might result in bias of the point estimates, waiting times for an appointment were truncated at 3 months for GPs and at 6 months for specialists, and waiting times within the practice were truncated at 3 h for GPs and at 4 h for specialists. The truncation of waiting time had no effect on the results.

For all four models, we hypothesised that waiting time (Y i ) is a function of type of insurance (INS i ), household income (INC i ), the reason for an appointment with the GP (RFA i ) (for model Ia and model Ib), and the control variables for socioeconomic, structural and practice characteristics as described above (X i ) as well as interactions between type of insurance and control variables (INS i × X i ). While β 0, β 1, β 2, β 3, β 4 and β 5 represent vectors of parameter estimates, e i represents the error term:

Waiting time for an appointment in days or waiting time in the practice in minutes is a classical parameter for the application of count data regression models because the four dependent variables (a) have non-negative integer values and (b) their distrbution is highly skewed to the left (overdispersed). The majority of individuals waited for only a short time, whereas a small number of individuals waited for longer periods. Therefore, we used negative binomial regression (Negbin) models to investigate the association between waiting time and our explanatory variables. The Negbin regression model provides a generalisation of the Poisson model, allowing for heterogeneity in the mean function, thereby relaxing the restriction on the variance.Footnote 19 We used the ln alphas to control for overdispersion and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to select and compare Poisson regression and Negbin.Footnote 20 In addition, the Vuong test was used to test if a zero-inflated Negbin model was an improvement compared to the standard Negbin model.

The four regression models were developed by first including the variables according to theoretical assumptions. Then, we used a forward stepwise regression technique to check for interactions and non-linear effects. At first, univariate regression models with each interaction variable were run to determine the order of variables entering the final model. Sequentially, interactions were included into the models if the models improved significantly according to the likelihood ratio test (P<0.05). In all four models, a weighted regression approach was applied. Weights were provided by the Bertelsmann Health care Monitor to ensure that the sample is representative for the general population with respect to age and gender. Marginal effects for the variable of interests were calculated with all variables set to their mean. To check robustness of results, multiple sensitivity analysis were conducted. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2.

Data

Sample and setting

We used data from a patient survey of the Bertelsmann Health care Monitor. The survey was conducted in Germany in five waves between 2007 and 2009. The survey included five cross-sectional samples of approximately 1,500 persons aged 18 to 79 years that previously was shown to be representative of the German population.Footnote 21 The survey included information on health status, socioeconomic characteristics and treatment provided along with characteristics of the physicians and their practices. The average response rate of each survey wave was approximately 70 per cent.

Variables of interest

The main explanatory variables included in the four waiting time models are type of health insurance and household income. In the GP models, we also included self-reported reason for the appointment. For type of health insurance, we differentiated between (1) SHI, (2) PHI, (3) SHI with refund and (4) other schemes. The “with refund” option of SHI allows patients to use the PHI reimbursement rates either by paying the difference between the SHI and PHI reimbursement out of pocket or through complementary insurance. Other schemes include special schemes for farmers, miners and sailors.

Household income captures the socioeconomic status of the respondent and was measured as the gross household income. It includes income from employment, self-employment, pensions, public benefits, private regular transfers, long-term care, capital income, rents and housing benefits. Along with income serving as socioeconomic variable, this variable also acts as a proxy for the ability to pay for health services that are not covered by SHI but are to be paid for either through PHI or out of pocket.

The reason for an appointment at the GP was originally assessed in 13 categories. We aggregated these into four categories: acute severe disease (original categories: acute severe disease, accident), acute mild disease (original categories: general discomfort, counselling), chronic condition (original categories: chronic disease, disability) and others (original categories: check-up, medical estimate, visit without seeing the doctor).

Other explanatory variables

Throughout the model, we controlled for a number of variables reflecting socioeconomic characteristics that can influence access to health care in general or waiting time for physician appointments in particular in previous studies.Footnote 22 Besides including variables for age and gender, we controlled for migration-specific sociocultural characteristics, by including a dummy variable for nationality. Another dummy variable indicated whether residency of the respondent was in an urban area (population >50,000 inhabitants) or in a rural area (population <50,000 inhabitants) to approximate supply and structural characteristics of health care services. We also included a dummy variable for handicap.

As a proxy for healthy lifestyle, we used the level of education.Footnote 23 The Bertelsmann Healthcare Monitor captures education as 16-categorical variable. These were grouped into six categories following the International Standard Classification (ISCED-97): high education (first and second stage of tertiary education), middle education, (upper secondary, post-secondary and non-tertiary education), low education, (primary and lower secondary education), in school (ongoing education), no education and other. In addition, employment status was included. We differentiated between training on-the-job, full-time employed, part-time employed and unemployed.

Besides characteristics of the respondent, we included the number of GP visits in the prior 12 months, the specialty of the GP, type of organisation (i.e. single practice, group practice or outpatient department of a hospital) and duration of the GP–patient relationship (categories: <1 year, <5 years, >5 years) into the GP models (models Ia and Ib) to control for structural characteristics of the care setting. Accordingly, the following variables were included in the specialist models (model IIa and IIb): number of specialist visits in the previous 12 months, specialty of the physician, and whether or not the respondent obtained a referral from a GP to visit a specialist. In addition, we included waiting time for an appointment with the GP in model Ib (waiting time in GP practice) and waiting time for an appointment with the specialist in model IIb (waiting time in specialist practice). Finally, we used time-fixed effects to control for differences between the five survey waves.

In case of a missing value, we assumed missing at random (MAR). The basic idea of MAR is that the probability that a response variable is observed depends on the values of those other variables which have been observed.Footnote 24 We tested for potential selection bias induced by missing data by using a Heckman selection model.Footnote 25 For our selection models we used the variable “living together with a partner in one household” as instrumental variable for model Ia (correlation between “waiting time for an appointment with the GP” and “living together with a partner in one household”: P=0.171; correlation between “missing response” and “living together with a partner in one household”: P<0.0001), for model IIa (correlation between “waiting time for an appointment with the specialist” and “living together with a partner in one household”: P=0.685; correlation between “missing response” and “living together with a partner in one household”: P=0.021) and for model IIb (correlation between “waiting time in the practice of a specialist” and “living together with a partner in one household”: P=0.533; “missing response” and “living together with a partner in one household”: P<0.0001). For model Ib we used the “estimate of own amount of sleep” as instrumental variable for the selection model (correlation between “waiting time for an appointment with the specialist” and “estimate of own amount of sleep”: P=0.442; “missing response” and “estimate of own amount of sleep”: P=0.000). As Rho was not significant throughout our models (Model Ia (Rho)=0.983; Model Ib (Rho)=0.690; Model IIa (Rho)=0.934; Model IIb (Rho)=0.995.) we concluded that selection bias is not an issue. Thus, we applied listwise deletion for the data which is analysed for the GP models and the specialist models.Footnote 26

Results

Table 1 displays the descriptive characteristics of the study sample. In total, the data set comprised data from 5,122 respondents in the GP models (model Ia and Ib) and 4,626 respondents in the specialist models (model IIa and IIb) who were evenly distributed among the survey periods. Descriptive statistics revealed that respondents reported waiting 2.8 days on average for an appointment with the GP and an average of 15.6 days for an appointment with the specialist. Respondents waited about the same amount of time at both types of practices, 31.5 min at the GP practice compared to 37.5 min at the specialist's practice. The majority of the study population (80.1 per cent in the GP models, 79.4 per cent in the specialist models) were SHI members; a total of 14.5 per cent in the GP models and 15.4 per cent in the specialist models were insured under PHI. The higher income groups (average income >€3,000/month) were under-represented with 27.2 per cent in the GP models compared to 25.3 per cent in the specialist models.

The results of the executed likelihood ratio tests revealed that for all the four regression models the p-values were highly significant with P<0.001, which meant that the full models constituted an improvement against the empty models.Footnote 27 Table 2 shows the results of the regression models.

Waiting time and type of insurance

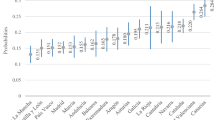

The type of insurance was a significant predictor for access to specialist care and there was a strong trend for type of insurance to predict access to care to the GP (P=0.0538). We found reverse results for waiting time in practice, as type of insurance had no effect on waiting time in the specialist practice but significantly affected waiting time in the GP practice. Marginal effects from our regression models revealed that respondents insured under PHI waited 56 per cent less (9 fewer days) for an appointment at the specialist than individuals with SHI (P<0.001) and 33 per cent less (1 less day) for an appointment with the GP (P=0.0538) (Figure 1). Compared to PHI, SHI with refund had no effect on access to care on waiting time for an appointment. Waiting time in the GP practice was also heavily determined by type of insurance. Respondents with PHI waited, on average, 32 per cent less or 10 fewer minutes (P=0.0088) than respondents with SHI. For the SHI with refund option the influence on waiting time in GP practice was not significant.

Waiting times for different income levels

Also, income had a major impact on waiting time for an appointment with the GP, whereas it had a modest influence on waiting time for an appointment with the specialist. A household income of more than €2,000/month on average was associated with a significant reduction in waiting time for a GP appointment compared to respondents with an income of less than €500 (28 per cent or 1 day less; P=0.0463). For the waiting time for an appointment with the specialist only a household income of more than €5,000/month was associated with significantly less waiting time (28 per cent or 5 days less; P=0.0315). Increased income also reduced waiting time in practices of GPs significantly for a monthly household income of more than €5,000 (38 per cent or 13.3 min less; <0.0001) (Figure 2).

Waiting time and reason for an appointment at the GP

The reason related to the consultation of a GP was also a significant predictor of access to care. Respondents with acute severe disease had to wait shorter times for an appointment than respondents who consulted their GP because of an acute mild disease (P<0.001), a chronic condition (P<0.001) or other reasons (P<0.001). However, the effect of the reason for appointment was much smaller compared to the effect of type of insurance. Respondents with acute mild disease waited on average 29 per cent more or 1 day longer for an appointment than those with acute severe disease.

Regarding the waiting time in the GP practices, we found reverse results. Respondents with acute severe disease waited longer than respondents with acute mild disease (P=0.0484), a chronic condition (P=0.001), or those who visited the GP for other reasons (P<0.001). This means that respondents with acute mild disease had shorter waiting time in practices compared to those with acute severe disease by waiting 8 per cent or 4 min less. Respondents with chronic conditions and respondents who consulted physicians for other reasons waited 14 per cent or 5 min less compared to those with acute severe disease.

Interactions

Although we controlled for interactions between type of insurance and all other independent variables, the strong effect of type of insurance remained. Few interaction effects were significant. The subgroup of insured under SHI with refund having mild acute disease experienced shorter waiting time in the GP practice (P=0.0268) compared to SHI insured with acute severe disease. For the waiting time in the specialist practice for surgery (P=0.0325) or urology (P=0.0042) respondents insured under PHI waited significantly less than SHI insured in the specialist practice for internal medicine (reference group).

Sensitivity analysis

We tested the robustness of our findings by performing multiple sensitivity analyses for the four models. At first, we re-estimated the models by varying truncation of the dependent variables. We also re-estimated the models without truncations. The results for the variables of interest became gradually less significant, but point estimates remained robust. Second, we included controls for the patient's self-reported chronic co-morbidities. We observed no effect on the results for our variables for type of insurance, income and reason for an appointment. Third, we controlled for the interaction between income levels and type of insurance, which, however, showed no significant effect. We further re-estimated the two models excluding either the variables for type of insurance or for household income. Household income became gradually more significant, but again, point estimates remained robust. We also checked for multicollinearity. In sum, our variables of interest seem to be robust to model changes.

Discussion

This study is among the first to examine the impact of type of insurance and income on waiting time in the German outpatient sector, using such a comprehensive set of explanatory variables. The rich data sample enabled us to include the insurance status and various socioeconomic and structural variables and characteristics of the GP and specialist practices in the four models of waiting time. This allowed us to obtain more consistent estimates for determinants of waiting time in the outpatient sector. Furthermore, our study adds value to existing research by introducing “waiting time in the GP or specialist practice” as an additional dimension of waiting time.

Our findings show evidence of inequality of access for those insured under PHI and SHI with refund compared to SHI. This is the case for waiting time in practices provided by the GP as well as for waiting time for an appointment with the specialist. Overall, the results suggest that membership in PHI plays a significant role for access to care. This might be due to three reasons. First, PHI allows higher reimbursement rates by the factor 2.28 for the same service compared to SHI.8 Second, PHI usually provides a more generous benefit package, that is, additional health care services, which are not covered under SHI. Thus, the physician is able to perform and bill a higher volume of service items per consultation. Finally, as partly shown by the negative correlation between household income and waiting time in practices, physicians seem to prefer patients with an increased willingness to pay because these patients are more likely to purchase (additional) health services out of pocket.

While the differences regarding type of insurance influenced waiting time in the practice at the GP, it did not influence waiting time in the practice at the specialist. One possible explanation for this discrepancy may be that the overall service provision, that is the type of services to be provided at a scheduled appointment, is more foreseeable at the specialist compared to the GP. Patients that consult a specialist usually will have a referral from another physician or at least some information on the disease that is to be treated when making the appointment, whereas at the GP most patients will make an appointment because they simply feel “sick” without being able to reveal information on the type of services to be provided at the appointment.

In addition, GPs have a higher percentage of walk-ins in Germany (49 per cent) compared to specialists (29 per cent).Footnote 28 So, GPs will get behind their schedule more often compared to the specialist. Thus, the decision between (a) making all patients wait a little longer and (b) treating the most profitable patient as scheduled (PHI patients) and making SHI patients wait much longer occurs much more frequently in GP practices compared to specialist. Taking into consideration the fact that the coefficients in both models have the expected signs for PHI compared to SHI patients, it might be that overcrowding in specialist practices (P=0.2108) still happens too infrequently for the effect to be significant.

While type of insurance influenced the waiting time for an appointment with the specialist, only a trend was found (P=0.0538) for waiting time for an appointment with the GP to decrease for PHI insured. This might also be attributed to the higher percentage of walk-ins for GP practices compared to specialists.

Furthermore, it is possible that the observed differences in waiting times are the results of a general tendency for waiting times to increase in the outpatient sector. SommerFootnote 29 reported that some physicians in the United Kingdom balloon their waiting lists. Thereby they aim at demonstrating that their department is under-equipped.29 While this may be true for the NHS-financed U.K. system, the argument does not hold for Germany, as physicians work on a self-employed basis. Also, reimbursement through fee-for-service incentivises physicians to treat as many patients as possible. Still, the increase in the number of the elderly and in patients with chronic diseases has led to a higher demand for outpatient services. In addition, there is the tendency towards generally more day cases and shorter length of stay in the hospital due to the introduction of Diagnosis Related Groups (DRG) reimbursement. The after-care of those cases is now often provided by physicians in the outpatient sector.Footnote 30

National and international empirical results also revealed that disparities in access to innovative treatments and shorter waiting times persist across different types of insurance.15 The study of Schellhorn14 supports our results for SHI to increase waiting time with the specialist and in the specialist office compared to PHI. In contrast to our results, however, waiting time for an appointment with the GP was not significantly different between SHI and PHI in Schellhorn's study and there were significant differences for waiting time in the GP office.14 Differences might be due to the different time periods of the two data sets and the difference in the measurement of waiting time. He measured waiting times in categories while we had access to waiting time measured as a continuous variable.

Calvin et al. Footnote 31 reported in his study that patients with Medicaid as the primary payer waited 21 hours longer for a coronary artery bypass grafting compared to patients with Health Maintenance Organization (HMO) or private insurance coverage. Dimakou et al. 16 reported that patients with PHI waited on average 99 fewer days for elective surgery compared to patients with National Health Service (NHS) coverage.16 In the study by Resneck et al. Footnote 32 the mean waiting time for Medicare patients and patients with HMO or private insurance coverage was 37 days for an appointment with the dermatologist, whereas patients with Medicaid experienced significant queuing and waited an average of 50 days.32 These findings were in line with our results.

We found that income has a modest effect on waiting time for an appointment and on waiting time in practices. Patients with higher income levels might have an increased willingness to pay for additional services that would be paid out of pocket and experience, thus, less waiting time for an appointment or in the practices. Therefore, physicians might try to motivate their patients to consult them on a private basis, which is associated with an additional income for the physicians.29 Our finding that income does not have a major impact on waiting time is at odds with the results obtained in other studies.Footnote 33 The study by Siciliani and Verzulli11 found an increase in income of €10,000 reduced waiting time for specialist consultation by 8 per cent in Germany.11 However, because Siciliani and Verzulli11 did not control for type of insurance, their results do not seem comparable to ours. Having included both variables, type of insurance and income, the former rather than the latter seems to determine waiting time.

Whereas income only has a modest effect for waiting time, the reason for an appointment has a strong impact on waiting times at GP practices. It is striking that patients with acute severe disease have shorter waiting times for an appointment but have longer waits in practices compared to patients with other reasons for visiting a physician. This might be because of GPs’ intentions not to turn away those with acute severe diseases who may need urgent care. However, once these individuals were able to skip the usual waiting list of several days, GPs may try to comply with their scheduled appointments within a given day. Thus, patients with acute severe disease may have been walk-ins who must wait longer than patients with scheduled appointments. As the interactions show, this is also true for patients with PHI coverage. Although patients with PHI generally wait shorter times, the “mark-up” for having an acute severe condition did not differ between those with PHI and SHI.

The results for the various control variables were as expected. For the variable “duration of GP-patient relationship” there was a weak trend for patients with a longer duration of GP-patient relationship to have longer waiting times in the office of the GP (P=0.0704 for 1–5 years compared to <1 year and P=0.0998 for⩾5 years compared to y<1 year) while duration GP-patient relationship did not impact waiting time for an appointment at the GP (P=0.7678 and P=0.6530, respectively). However, it is uncertain whether the patient simply perceived to have waited more in the office of the GP due to the increased familiarity with the practice staff or whether the patient really waited more the longer the GP-patient relationship.Footnote 34 This study also has important limitations. First, due to its design using a patient survey, information on GPs, specialists and their practices is limited. Hence, it is not possible to control for the experience of the physicians or their receptionists in assessing the need of patients seeking access to care. Second, the data does not permit controlling for the exact time of day for the appointment. This could be important because people with higher incomes generally will be more restricted to office hours than people with lower income who have a larger percentage of part-time workers.Footnote 35 Controlling for time of appointment may thus even increase the difference in waiting times between patients with PHI and SHI as well as the effect of household income on waiting times. Third, as in many studies relying on survey data, the variables are self-reported. Other studies argued that self-reported waiting times by patients tend to be overestimated compared to actual waiting times.Footnote 36 The same reason may also introduce bias to our variable of interest “reason for an appointment”, because the perception of what is acute or severe might vary. Fourth, socioeconomic characteristics are, at least partly, related to type of insurance, although we could not identify a correlation in our model. Interactions between type of insurance and income did not affect results, but P-values might still be biased downward due to overlapping variance of both variables. A final consideration is that 53 per cent of the patients with SHI received a referral from their GP before they visited a specialist, whereas only 3.5 per cent with PHI obtained a referral. This means that for patients with SHI waiting time for an appointment in specialist practices is likely to be underestimated as every second SHI insured has waited an unobserved additional time period for an appointment at the GP practice before the specialist consultation.

Conclusion

Our study has shown that inequalities in waiting time in the outpatient sector exist. Although results for reason for appointment were as expected, that is the more severe a condition the faster a patient could get access to health care, our results also show that there are inequalities in access to healthcare regarding type of insurance and income. If disparities in access to health care exist, one could assume that disparities for different types of insurance also persist regarding the quality of care. Thus, it is not clear whether the overall quality of treatment is influenced by type of insurance. We recommend analysing if SHI might provide better health-care services or health-care quality because of the existence of Disease Management Programs (DMP), which are not available for PHI insured. This has to be considered in future research.

Different policy instruments could be considered to prevent inequalities in access to care. Currently the treating physician receives different reimbursement for the same medical service for PHI and SHI patients. On average, the remuneration rate for PHI patients is 2.28 times more than for SHI patients.8 This seems to have an influence on access to outpatient care regarding waiting times. Therefore, a harmonisation in the reimbursement rates between SHI and PHI may reduce differences.

Above harmonisation of reimbursement rates there may be other instruments to improve access to care. Promising examples can also be found in other countries. An innovative online booking platform has recently been launched in Philadelphia (DocAsap.com). This platform intends to match patient's demand for more timely treatment with available doctor appointments, taking into account patient's preferences without knowing their socioeconomic status. In the United Kingdom the NHS provides an online booking system at medical centres. When booking an appointment, patients need to enter the reason for their appointment. Another innovative approach is “same-day scheduling” where an appointment is provided on the same day. This type of practice scheduling has shown promise in reducing patient waiting times and increasing the practice efficiency in the outpatient sector in Canada.Footnote 37 Overall these approaches might reduce discrepancies of waiting times across individuals with different socioeconomic characteristics and types of insurance. However, it is not clear if the above-mentioned policy instruments are able to reduce waiting time in physician's practices.

Notes

References

Aday, L. and Andersen, R. (1974) ‘A framework for the study of access to medical care’, Health Services Research 9: 208–220.

Akaike, H. (1974) ‘A new look at the statistical model identification’, IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control 19: 716–772.

Barzel, Y. (1974) ‘A theory of rationing by waiting’, Journal of Law and Economics 17 (1): 73–95.

Breyer, F. (2004) ‘How to finance social health insurance: Issues in the German reform debate’, The Geneva Papers on Risk and Insurance—Issues and Practice 29: 679–688.

Calvin, J., Roe, M., Chen, A., Mehta, R., Brogan, G., DeLong, G., Fintel, D., Gibler, W., Ohman, E. and Smith, S. (2006) ‘Insurance coverage and care of patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes’, Annals of Internal Medicine 145: 739.

Cameron, A. and Trivedi, P. (1998) Regression Analysis of Count Data, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cameron, S., Sadler, L. and Lawson, B. (2010) ‘Adoption of open-access scheduling in an academic family practice’, Canadian Family Physician 56: 906.

Campbell, S., Roland, M., Quayle, J., Buetow, S. and Shekelle, P. (1998) ‘Quality indicators for general practice: Which ones can general practitioners and health authority managers agree are important and how useful are they?’ Journal of Public Health 20: 414.

Cheng, P.E. (1994) ‘Nonparametric estimation of mean functionals with data missing at random’, Journal of the American Statistical Association 89 (425): 81–87.

Cooper, Z, McGuire, A., Jones, S. and Grand, J. (2009) ‘Equity, waiting times, and NHS reforms: Retrospective study’, British Medical Journal, 339.

DeCoster, C., Carriere, K, Peterson, S., Walld, R. and MacWilliam, L. (1999) ‘Waiting times for surgical procedures’, Medical Care 37 (6): 187.

Dimakou, S., Parkin, D., Devlin, N. and Appleby, J. (2009) ‘Identifying the impact of government targets on waiting times in the NHS’, Health Care Management Science 12 (1): 1–10.

German Federal Association of the Company Health Insurance Funds (2008) Die BKK, Berlin: German Federal Association of the Company Health Insurance Funds.

Gravelle, H. and Siciliani, L. (2008) ‘Optimal quality, waits and charges in health insurance’, Journal of Health Economics 27: 663–674.

Hargraves, J. and Hadley, J. (2003) ‘The contribution of insurance coverage and community resources to reducing racial/ethnic disparities in access to care’, Health Services Research 38: 809–829.

Heckman, J.J. (1979) ‘Sample selection bias as a specification error’, Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society 47 (1): 153–161.

Johar, M, Jones, G., Keane, M., Savage, E. and Stavrunova, O. (2011) ‘Waiting times for elective surgery and the decision to buy private health insurance’, Health Economics 20 (1): 68–86.

Jones, M.P. (1996) ‘Indicator and stratification methods for missing explanatory variables in multiple linear regression’, Journal of American Statistical Association 91: 222–230.

Kennedy, J., Rhodes, K., Walls, C. and Asplin, B. (2004) ‘Access to emergency care: Restricted by long waiting times and cost and coverage concerns’, Annals of Emergency Medicine 43: 567–573.

Krobot, K., Miller, W., Kaufman, J., Christensen, D., Preisser, J. and Ibrahim, M. (2004) ‘The disparity in access to new medication by type of health insurance: Lessons from Germany’, Medical Care 42: 487.

Lantz, P., House, J., Lepkowski, J., Williams, D., Mero, R. and Chen, J. (1998) ‘Socioeconomic factors, health behaviors, and mortality: Results from a nationally representative prospective study of US adults’, Journal of the American Medical Association 279 (21): 1703.

Lofvendahl, S., Eckerlund, I., Hansagi, H., Malmqvist, B., Resch, S. and Hanning, M. (2005) ‘Waiting for orthopaedic surgery: Factors associated with waiting times and patients’ opinion’, International Journal for Quality in Health Care 17 (2): 133.

Murray, M. and Berwick, D. (2003) ‘Advanced access: Reducing waiting and delays in primary care’, Journal of the American Medical Association 289 (8): 1035.

Newacheck, P., Hughes, D. and Stoddard, J. (1996) ‘Children's access to primary care: Differences by race, income, and insurance status’, Pediatrics 97 (1): 26.

Pell, J., Pell, A., Norrie, J., Ford, I., Cobbe, S. and Hart, J. (2000) ‘Effect of socioeconomic deprivation on waiting time for cardiac surgery: Retrospective cohort study commentary: Three decades of the inverse care law’, British Medical Journal 320 (7226): 15.

Potthoff, P, Heinemann, L. and Güther, B. (2004) ‘A household panel as a tool for cost-effective health-related population surveys: Validity of the healthcare access panel’, German Medical Science 2: DOC05.

Prentice, J. and Pizer, S. (2007) ‘Delayed access to health care and mortality’, Health Services Research 42 (2): 644–662.

Resneck, J., Pletcher, M. and Lozano, M. (2004) ‘Medicare, medicaid, and access to dermatologists: The effect of patient insurance on appointment access and wait times’, Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 50 (1): 85–92.

Rosanio, S., Tocchi, M., Cutler, D., Uretsky, B., Stouffer, G., deFilippi, C., MacInerney, E., Runge, S., Aaron, J. and Otero, J. (1999) ‘Queuing for coronary angiography during severe supply-demand mismatch in a US public hospital: Analysis of a waiting list registry’, Journal of the American Medical Association 282 (2): 145.

Schellhorn, M. (2007) ‘Vergleich der Wartezeiten von gesetzlich und privat Versicherten in der ambulanten ärztlichen Versorgung’, in J. Böcken, B. Braun and R. Amhof (eds.) Gesundheitsmonitor 2007. Gesundheitsversorgung und Gestaltungsoptionen aus der Perspektive von Bevölkerung und Ärzten, Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Foundation, pp. 95–113.

Schoen, C. and Doty, M. (2004) ‘Inequities in access to medical care in five countries: Findings from the 2001 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey’, Health Policy 67 (3): 309–322.

Schoen, C., Osborn, R., Doty, M.M., Bishop, M., Peugh, J. and Murukutla, N. (2007) ‘Toward higher-performance health systems: Adults’ health care experiences in seven countries’, Health Affairs 26 (6): 717–734.

Schreyögg, J., Stargardt, T., Tiemann, O. and Busse, R. (2006) ‘Methods to determine reimbursement rates for diagnosis related groups (DRG): A comparison of nine European countries’, Health Care Management Science 9: 215–223.

Siciliani, L. and Hurst, J. (2004) ‘Explaining waiting times variations for elective surgery across OECD countries’, OECD Economic Studies 38 (1): 95–123.

Siciliani, L. and Verzulli, R. (2009) ‘Waiting times and socioeconomic status among elderly Europeans: Evidence from SHARE’, Health Economics 18 (11): 1295–1306.

Sommer, J.H. (ed.) (1999) Gesundheitssysteme zwischen Plan und Markt, Stuttgart: Schattauer.

Starfield, B. Primary care (1992) Concept, Evaluation, and Policy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sudano, J. and Baker, D. (2006) ‘Explaining US racial/ethnic disparities in health declines and mortality in late middle age: The roles of socioeconomic status, health behaviors, and health insurance’, Social Science & Medicine 62 (4): 909–922.

The Federal Ministry of Health (2010) ‘Statistiken zur gesetzlichen Krankenversicherung’, from www.bundesgesundheitsministerium.de/cln_169/nn_1193098/DE/Gesundheit/Statistiken/gesetzliche-krankenversicherung_node.html?_nnn=true#doc1193102bodyText2, accessed 7 October 2010.

Van Doorslaer, E., Masseria, C. and Koolman, X. (2006) ‘Inequalities in access to medical care by income in developed countries’, Canadian Medical Association Journal 174 (2): 177.

Walendzik, A., Greß, S., Manouguian, M. and Wasem, J. (2008) ‘Vergütungsunterschiede im ärztlichen Bereich zwischen PKV und GKV auf Basis des standardisierten Leistungsniveaus der GKV und Modelle der Vergütungsangleichung’, Discussion Paper: Fachbereich Wirtschaftswissenschaften, Universität Duisburg-Essen.

White, G.C. and Bennetts, R.E. (1996) ‘Analysis of frequency count data using the negative binomial distribution’, Ecology 77 (8): 2549–2557.

Zuvekas, S. and Taliaferro, G. (2003) ‘Pathways to access: Health insurance, the health care delivery system, and racial/ethnic disparities, 1996–1999’, Health Affairs 22 (2): 139.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Roll, K., Stargardt, T. & Schreyögg, J. Effect of Type of Insurance and Income on Waiting Time for Outpatient Care. Geneva Pap Risk Insur Issues Pract 37, 609–632 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2012.6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/gpp.2012.6