Abstract

This chapter addresses the following research questions: (i) Are firms characterized by international linkages more productive than other firms? (ii) Are those belonging to industries more involved in GVCs even more productive? To this end, we combine the World Bank Enterprise Survey dataset with the new OECD-WTO TiVA dataset and present three main empirical exercises: (1) an analysis of productivity premia associated with participation in international trade and presence of inward FDI; (2) a Cobb–Douglas output function expanded to firms’ international linkages; (3) a further expanded version of the above relationship including the TiVA-based indicators of value added trade and industry participation and position in the global value chain. Our empirical outcomes confirm the presence of a positive causal relationship between participation in international activities and firm performance in the LAC region. Focusing on four big Latin American countries we show that the actual level of involvement into GVCs matters as well.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Foreign Direct Investment

- Firm Performance

- World Trade Organization

- Firm Productivity

- International Linkage

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

One of the key issues in the current empirical debate on the determinants of firm performance is the influence of international linkages. The aim of this chapter is to study the causal relationship between international linkages and firm performance in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC). The notion of international linkages adopted in this analysis includes two different dimensions: participation in international trade and inward Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). To this end, we take advantage of recent firm-level data provided by the World Bank Enterprise Survey (WBES). Moreover, by matching WBES firm-level data with the new Trade in Value Added (TiVA) dataset by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the World Trade Organization (WTO), we provide a richer picture of the relationship between firm performance and country/industry involvement in international production networks in the LAC region. In particular, this chapter addresses the following research questions:

-

1.

Are firms characterized by international linkages more productive than firms that are not?

-

2.

Are firms that belong to industries more involved in global value chains (GVCs) even more productive?

To empirically derive the causal relationship between firms performance and their international linkages we provide:

-

1.

A static analysis of productivity premiums associated with participation in international trade and inward FDI.

-

2.

A version of the standard Cobb–Douglas output function expanded to a firm’s international linkages.

-

3.

A further expanded version of the above relationship including indicators of value added trade as well as the degree and type of industry involvement in GVCs.

In carrying out the empirical exercises, we control for heterogeneity among firms by country, industry, and survey waves, and for endogeneity bias by using instrumental variables and control function techniques.

Our empirical outcomes confirm a positive causal relationship between participation in international activities and firm performance in LAC. Focusing on four big LAC countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico), we show that the extent of involvement in GVCs matters as well. More specifically, we highlight the key role of both trade in value added and GVC position, with a positive impact of upstreamness on firm performance. These empirical results also appear relevant for policymaking.

In the next section, we review the literature on international linkages and firm productivity, and then we describe how to trace a country’s production of value-added as well as their level of integration in global markets. Next we report some stylized facts about the main characteristics of LAC firms related to internationalization and the relevant GVC indicators. The next section presents the empirical analysis, and finally we provide some conclusions.

International Linkages and Firm Productivity: Review of the Literature

Participation in international trade can be an important source of information, knowledge spillovers, technology transfers, technical assistance, competitive pressures, and other productivity advantages for firms, leading to significant performance improvements (Grossman and Helpman 1991; Clerides et al. 1998; Verhoogen 2007; Fafchamps et al. 2008; Bernard et al. 2003). At the same time, firms with FDI and/or multinational firms may generate a total cost reduction through low-priced production factors. All of these factors may generate a positive learning effect of global activities. This “learning-by-exporting” hypothesis has spurred a large number of empirical studies that seek to assess the causal effect of exporting at the firm level. 1 However, there is no consensus among scholars on whether such a learning effect exists or what specific factors may be behind it. While a comprehensive survey by Wagner (2007) indicated that the evidence on this learning effect was mixed and unclear, a significant positive effect of the export experience on firm productivity has been found in several studies. 2 The meta-analysis conducted by Martins and Yang (2009) indicated that the impact of exporting on productivity was higher for developing than for developed economies. Most importantly, the direction of causality between openness and firm performance is controversial (see Greenaway and Kneller 2007).

Firm productivity and sunk costs play important roles in how firms select international activities. These costs tend to discourage less productive firms from international linkages; therefore, firms generally self-select to participate in global markets. This selection mechanism according to the level of productivity is called the “selection effect” in exporting. Melitz (2003), who showed that exporting firms had relatively higher productivity, has provided the theoretical benchmark for the above selection mechanism, while the pioneering empirical work by Bernard and Jensen (1999) on US firms has been followed by many scholars. López (2005), Greenaway and Kneller (2007), and Wagner (2007) have done surveys on the topic. Most of the studies on the selection effect found that more productive producers self-select into the export market (Clerides et al. 1998; Álvarez and López 2005; Hayakawa et al. 2012).

Identifying the learning effects of FDI is also important. On the one hand, the performance of domestic firms may improve with FDI, particularly inward FDI in the form of cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&A). Fostered by superior know-how, human capital, and organization of foreign firms, local firms with FDI could strengthen their local advantages (i.e. experience in the local market and knowledge of the local institutional environment) and enhance their productivity (see UNCTAD’s World Investment Reports from various years). On the other hand, Helpman et al. (2004) theoretically showed that investing firms have relatively high productivity. Several studies have empirically tested this proposition (see Greenaway and Kneller 2007, for a survey within this literature). 3 Studies do not necessarily detect a positive causal effect of investing on firm productivity. While Barba Navaretti and Castellani (2004) and Kimura and Kiyota (2006) found significant positive impacts, Aitken and Harrison (1999), Hijzen et al. (2007), and Ito (2007) detected a small or non-positive effect. Hijzen et al. (2006) and Barba Navaretti et al. (2006) further explored a possible qualitative difference in learning related to two types of FDI: horizontal (many plants doing the same activities in a number of countries to put production near consumers) and vertical (different stages of production in different countries). For French firms, they found positively significant enhancements in productivity from horizontal FDI but not from vertical FDI. Other papers have focused specifically on the impact of M&A on firm performance, and most have found a significant positive impact. 4

Trade in Valued Added and GVCs: Definition and Measurement

The increasing international fragmentation of production that has occurred in recent decades has challenged the conventional wisdom on how we look at and interpret trade. Traditional measures of trade record gross flows of goods and services each and every time they cross borders, leading to a multiple counting of trade, which may lead to misguided empirical analyses (Cattaneo et al. 2013; OECD–WTO 2012). Furthermore, since these days a large number of countries have developed comparative advantages in specific parts of the value chains and not necessarily on final goods, standard trade statistics are becoming much less informative.

Tracing Trade in Value Added

The relevance of this issue is confirmed by the many initiatives and efforts that try to address the measurement of trade flows in the context of the fragmentation of world production and try to estimate the so-called trade in value added. Value added reflects the value that is added by industries in producing goods and services. It is equivalent to the difference between industry output and the sum of its intermediate inputs. Looking at trade from a value added perspective reveals better how upstream domestic industries contribute to exports, as well as how much (and how) firms participate in GVCs (OECD–WTO 2012). The overall perspective is shifting from exports to imports. In a world of international fragmentation, access to efficient imports matters as much as access to markets (Ahmad 2013).

A new literature has emerged regarding tracing the value added of a country’s trade flows by combining input–output tables with bilateral trade statistics and proposing new indicators. 5 In addition, advanced research on constructing appropriate databases is also being conducted by the WTO and the OECD. However, the interpretation of these indicators and results for individual countries in the temporal, geographic, and industry dimensions are still in progress and pose new challenges to scholars and policy experts. In this chapter, we use data from the OECD-WTO TiVA database, which aims to track global production networks and value chains better. 6 This dataset presents three clear advantages with respect to its main counterpart, the World Input-Output Database (WIOD). First, the TiVA covers four big LAC countries instead of two. Second, it presents a set of ready-to-use trade in value added decompositions and GVC indicators. Third, it links the OECD Inter-Country Input-Output (ICIO) tables using the Bilateral Trade Database in goods by Industry and End-use category (BTDIxE) and estimates of bilateral trade flows in services. 7

Trade in Value Added and GVC Indicators

Our aim is to go beyond the information provided by standard trade statistics. Specifically, we gather a set of TiVA indicators to map country trade relations and describe the competitiveness of country industries by looking at their production of value added and their level of integration in global markets. These indicators are (i) the decomposition of the value added embodied in national exports, (ii) the participation in GVCs, and (iii) the position in GVCs.

We follow the decomposition of the value added embodied in national gross exports proposed by Koopman et al. (2011). According to this methodology, gross exports can be decomposed into the following components (see Fig. 9.1):

Gross export decomposition in value added

Source: Adapted from Koopman et al. 2011

-

(1a) Direct domestic value-added embodied in exports of goods and services (DVA), which reflects the direct contribution made by an industry in producing a final or intermediate good or service for export (i.e. value added exported in final goods or in intermediates absorbed by direct importers).

-

(1b) Indirect domestic value added embodied in intermediate exports (IVA), which reflects the indirect contribution of domestic supplier industries of intermediate goods or services used in the exports of other countries (i.e. value added exported in intermediates re-exported to third countries).

-

(1c) Re-imported domestic value added embodied in gross exports (RVA), which reflects the domestic value added that was exported in goods and services used to produce the intermediate imports of goods and services used by the industry (i.e. exported intermediates that return home).

-

(2) Foreign value-added embodied in gross exports (FVA), which reflects the foreign value added content of intermediate imports embodied in gross exports (i.e. other countries domestic value added in intermediates used in exports).

In Fig. 9.1, components 1a, 1b, and 1c represent the value of exports that is created domestically (i.e. the domestic value added, or DoVA), while component 2 shows the value of exports created abroad. Only components 1b, 1c, and 2 can be thus considered part of the GVC framework.

By combining these value-added components it is possible to assess both the level of participation and whether a country (or industry) is located upstream or downstream in the global production chain. Thus, a first indicator, namely the GVC participation index, takes into account the IVA and the FVA to summarize the importance of global production chains in country (or industry) exports. The higher (or lower) the value of the index, the larger (or smaller) is the participation of a country in GVCs. It is worth noting that a high IVA component shows the importance of domestic production in GVCs, while a high FVA component reveals that the country/industry is deeply embedded in GVCs but only captures a small part of the value added.

To complete information on international integration into global markets, we present a second index that characterizes the position of country (or industry) exporters in GVCs: the GVC position indicator. This measures the level of involvement of a country (or industry) in vertically fragmented production. It is determined by the extent to which the country (or industry) is upstream or downstream in the GVCs, depending on its specialization (Koopman et al. 2011). A country lies upstream either if it produces inputs and raw materials for others, or it provides manufactured intermediates or both; a country lies downstream if it uses a large portion of intermediates from other countries to produce final goods for export (i.e. it is a downstream processor or assembler adding inputs and value toward the end of the production process). The position indicator is given by the ratio of the IVA exports and the FVA exports. Since at the global level IVA and FVA equal each other, the average IVA/FVA ratio is equal to 1. Therefore, a ratio larger than 1 indicates the country lies upstream, while a ratio lower than 1 means the country lies downstream in the GVCs. 8 Since two countries can have identical GVC position index values in a given sector but very different degrees of GVC participation, it is important to look at both of these indicators to obtain a correct picture of the degree of integration of a country in GVCs (Koopman et al. 2011).

Firm Characteristics in LAC and Trade in Valued Added Performance: A Descriptive Analysis

Enterprise-level data offers crucial information to understand the drivers of productivity and competitiveness, as aggregate performance depends strongly on firm-level factors such as size, ownership, and technological capacity. For our empirical exercise, we use a subset of the WBES database specifically focused on firms in LAC countries. This subset provides information on the characteristics of firms across various dimensions, including size, ownership, trading status, and performance, and collects data for 14,657 firms and 31 LAC countries. 9 Table 9.6 in the Appendix presents information about the international linkages we analyze (exports, imports, and foreign-owned firms) for the whole LAC sample by country and survey year. In addition, in order to provide a richer picture of the phenomena we analyze (and to combine different levels of aggregation) and to map out sources and components of trade in value added, we use the OECD-WTO TiVA dataset by industry (see “Trade in Valued-Added and GVCs” above). We focus specifically on the following countries for which TiVA and WBES data are both available for the same fiscal year: Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. 10 Looking at all of the data on firms and industries, we can draw a picture of the current international linkages of the four LAC countries as well as trade in value added components and GVC characteristics.

Table 9.1 presents a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of the firms’ international linkages (WBES) and GVC indicators (TiVA) for the four LAC countries. 11 The WBES subsample includes 5120 firms across the four countries. The first five columns of Table 9.1 (WBES data) show that, overall, almost 15 % of these firms declare themselves to be exporters 12 and their export intensity is on average more than 33 % of their total sales. 13 Only 8.5 % are foreign-owned firms, but on average foreign investors own a significant share (85.4 %). The level of firm internationalization is heterogeneous across these four countries. With regards to international trade, Argentina has the highest number of exporting firms (over 27 %), followed by Chile (17 %), Mexico (15 %), and Brazil (7 %). Chile shows the highest export intensity (42 %), followed by Mexico (36 %), Argentina (33 %), and Brazil (30 %). With regards to FDI, Chile and Argentina have the highest number of foreign-owned firms (both around 13 %), while Brazil has the lowest (4 %). The foreign ownership share of these firms is high, ranging from about 83 % in Mexico to nearly 90 % in Argentina.

Concerning trade in value added components, columns 6 to 9 in Table 9.1 (TiVA data) present the main components of the decomposition of the overall gross exports described in Fig. 9.1 by country (IVA and FVA). The last two columns provide some perspective on the role and position in GVCs by country, using the indicators of GVC participation and position illustrated in the “Trade in Valued-Added and GVCs” section above.

The reported decomposition components show some degree of heterogeneity among the countries. Specifically, Chile has the highest IVA value, suggesting it provides relatively higher domestic added value inputs to other countries’ exports. This is followed by Brazil and Argentina, with Mexico having the lowest value, which is in line with its relative specialization in processing foreign inputs. On the other hand, Argentina and Brazil show, on average, a lower level of FVA, suggesting they contribute to their gross exports mainly with domestic value added, relying less on imported inputs. This can be related to the fact that these countries are, on average, more involved in exporting goods in which the main source of inputs comes from the primary domestic sector (Blyde 2014). We note that Brazil shows the smallest share of FVA—only 9 % of the value added incorporated in the Brazilian exports comes from other countries. On the other hand, Chile and Mexico show a relatively higher level of FVA, suggesting a relevant presence of foreign inputs in their overall exports. It is worth noting that about 30 % of the value of Mexican processing exports comes from abroad. This heterogeneity is associated to some extent with the country dimension (Cattaneo et al. 2013), but also with differences in the patterns of specialization: a relative specialization in producing primary goods requires, on average, less imported inputs than manufacturing them.

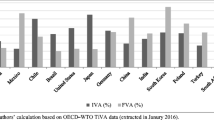

Figure 9.2 presents the international comparison of the value added decomposition for selected industrialized, emerging, and developing/transition economies, 14 as well as the sample of LAC countries. Other than Mexico, the LAC countries show a relatively high level of IVA but generally lower FVA (i.e. a lower content of intermediate inputs coming from abroad). This confirms the relative specialization of LAC countries within GVCs in exports of primary goods. In Table 9.7 in the Appendix, we provide the details of the main value added components of gross exports for the countries in Fig. 9.2.

Figure 9.3 provides an international comparison of the GVC participation and GVC position indicators. The figure shows that Chile’s GVC participation is substantial, Mexico’s is somewhat lower, and Argentina’s and Brazil’s are below the selected world counterparts, except for South Africa. This heterogeneity may be attributed to a size effect (i.e. larger economies tend to have a relatively higher degree of self-sufficiency in producing inputs for exports: Brazil and Argentina) and/or patterns of specialization (relatively high specialization in manufacturing can justify a higher degree of global participation: Chile and Mexico). This empirical evidence is consistent with similar analyses of LAC integration into the global production network (see UNCTAD 2013; Blyde 2014).

As stated in the “Trade in Valued-Added and Global Value Chains” section above, the GVC position index reflects where countries fit in the value chain. A country can be upstream or downstream, depending on its specialization. Upstream countries produce inputs and/or raw materials used at the beginning of the production process and do not rely on foreign inputs for their exports. Downstream countries assemble products and provide relatively less intermediates to the exports of other countries. The higher the value of the index (higher than 1), the more upstream the country’s exporters are in GVCs. In general, the sample of LAC countries is upstream (i.e. away from the final customer) in GVCs more than their international counterparts; however, again, there is a degree of heterogeneity. Brazil is the most upstream and has the highest GVC position in our international comparison. This is consistent with the fact that Brazil, more specialized in natural resources, mainly provides inputs to other countries’ exports and does not rely much on other countries’ inputs. Thus, Brazil is positioned more at the beginning of the GVCs. On the opposite side is Mexico, which is located more at the end of GVCs and acts as a final producer, using inputs provided by upstream countries in the form of maquila (factory) processing operations (Contreras et al. 2012; De La Cruz et al. 2011; Dussel Peters 2003) and does not provide many intermediates to other countries’ exports.

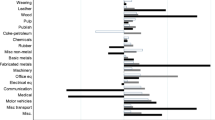

Figure 9.4 presents the comparison of the GVC position indicator by industry for the four big LAC countries. We provide an international comparison with the selected counterparts in Table 9.8 in the Appendix. The indicator used for the industry analysis is obtained from TiVA data, as proposed by Fally (2012) and Antràs et al. (2012). 15 In line with the literature, industries such as mining and quarrying, wood, paper, paper products, printing and publishing, chemicals and non-metallic mineral products, and basic metals and fabricated metal products are at the highest level of upstreamness since they provide raw materials and inputs for the beginning of the value chain. Among those industries, the big LAC countries (except Mexico) show relatively high specialization, with a degree higher than 2. Brazil has the highest index of upstreamness in mining and quarrying, with a value higher than 3.5. Concerning services, Fig. 9.4 shows that the most upstream services are, on average, telecommunications and financial. Of the LAC countries, Chile is positioned more upstream in the value chain in all the services sectors, while Mexico, in line with the result at the aggregate level is, on average, the most downstream, with the relevant exception of financial intermediates.

The Econometric Analysis

The aim of our empirical exercise is to investigate whether LAC firms characterized by international linkages have higher productivity than other LAC firms. Specifically, we want a more in-depth assessment of whether there is a causal relationship between the degree and type of involvement in international production networks and firm performance in the LAC region.

We start by presenting static differences in firm productivity premia between exporters and non-exporters, and foreign-owned 16 and domestic enterprises. First we pool data for the entire sample of LAC countries included in the WBES. Productivity premia are measured as the coefficients for export and inward FDI dummies in a regression of the form:

where θ i is the log of firm labor productivity, 17 d i is a set of dummies for exporting firms and firms characterized by foreign ownership (i.e. our proxy of inward FDI); η c and η j are dummies for country and industry, respectively, to control for bias due to unobserved factors; ε i is the error term. Table 9.2 confirms the expected positive relationship between international linkages and firm productivity based on firm-level data. These findings are in line with the theoretical predictions that low-productivity firms stay in the domestic market, while firms with higher productivity export and/or engage in FDI (Helpman et al. 2004).

So far we have presented stylized facts, which cannot yet allow any causal interpretation. Taking advantage of the availability of the set of firm-level covariates provided by the WBES, we can test the above relationship by presenting a version of the standard constant returns to scale Cobb–Douglas production function with labor, capital, and knowledge expanded to international linkages as follows:

Equation 9.2 adds the following explanatory variables (all variables are in logs) to equation 9.1: k i for firm “capital intensity” and z i for a bundle of firm-level observables (human capital, employment, firm size, and technological innovation). As in Farole and Winkler (2012), the latter variable is a dummy that controls whether firms use technology licensed from a foreign-owned company (excluding office software), their own internationally recognized quality certification (e.g. ISO), or use a firm website and/or email to communicate with clients and suppliers. To avoid bias due to unobservable factors, 18 we control for the geographical location and industry of the firms. A full description of the above variables is provided in Table 9.9 in the Appendix.

Table 9.3 shows the regression results of the base model. It is organized in ten columns. The first five columns report the estimates for equation 9.2. Columns 6 to 10 report the same estimates for the subsample of exporting firms by substituting the dummy variable for exports with a continuous variable (i.e. the value of sales exported directly). Also in this case, we use pooled data for the entire LAC dataset. The signs of the relationship between labor productivity and the set of firm-level explanatory variables are significant and consistent with the theory. A positive coefficient is estimated for the relationship between labor productivity, capital intensity, employment, and innovation, while a negative coefficient is estimated for unskilled workers (a proxy of human capital). Also in this case, on average and all else being equal, our findings are consistent with the view that exporter and/or foreign-owned firms (i.e. characterized by inward FDI) show higher productivity. To look more in depth at firm heterogeneity, we also carried out separate regressions by firm size (distinguishing micro, small, medium, and large firms). On average and all else being equal, the subsample of exporting firms (columns 6 to 10) confirms the positive relationship between the level of gross exports and productivity for all of the size categories.

Because of the lack of panel data, our base model cannot avoid further bias due to unobserved characteristics that are correlated with firm characteristics and productivity. To this end, we provide additional empirical estimates for the subsample of exporting firms located in the LAC region by controlling for endogeneity bias in the relationship between firm productivity and the value of their gross exports with excluded instruments. More specifically, from the WBES dataset we select some additional explanatory firm-level variables that are supposed to be correlated with gross exports but not with domestic productivity: average time to clear imports from customs (days), and days to obtain import license. We use these variables as proxies for international trade obstacles that are negatively correlated with export flows but do not depend on firm productivity. 19

Table 9.4 provides estimates for an instrumental variable (IV-2SLS) and a control function (CF) for the pooled data (the first stage estimates are not reported in the table). The IV results are robust and significant. Moreover, the Hansen’s J statistics of over-identifying restrictions—which is consistent in the presence of heteroskedasticity—does not reject the null hypothesis that our instruments are valid. However, the Angrist-Pischke (AP) F-statistic of weak identification is significant only at the 5 % level. Since the IV inconsistency increases with the number of instruments used, we opt for more parsimonious behavior by using only one instrument, the average time to clear imports from customs. Further, we apply a CF approach that controls for the endogeneity bias by directly adding the estimated residual of the first stage equation to the main regression providing an unbiased CF estimator that is generally more precise than the IV estimator (Wooldridge 2010). The significance of the CF estimates confirms the above evidence of a relationship between trade and firm-level productivity for the full sample and by firm size (with the exception of small firms) 20 as well as the absence of reverse causality. 21

Finally, we provide a more detailed investigation of the linkages between firm-level exports and productivity and specifically address our second research question, which is related to the effect of firm involvement in GVCs (participation and position) on firm productivity. Thus, we present a further empirical test of equation 9.2 for the subsample of exporting firms by controlling for the decomposition of the value added embodied in national exports as well as the GVC indicators at the industry level. This further test assumes that firm performance in value added trade is heterogeneous across industries but homogeneous within them. We acknowledge this is a strong assumption. However, it is consistent with the high level of aggregation of TiVA industry data that supports the hypothesis of firm heterogeneity across industries. It is also consistent with detailed investigations at the industry level that show a very low degree of firm heterogeneity across sector functions in the LAC region (Gereffi et al. 2005; Pietrobelli and Rabellotti 2011). However, we empirically test this assumption by applying a Levine test (i.e. similar to the standard ANOVA test but less sensitive to the violation of normality assumption) to a set of firm characteristics. The outcomes of the Levine test confirm, on average, that we can reject the null hypothesis that the “within variances” of the set of firm-level characteristics across industries are equal (with a probability below 0.05). This strongly supports the assumption of intra-industry firm homogeneity across ISIC industries and, thus, the relative homogeneity in value added trade across industries.

Before presenting this further empirical test, it is worth recalling that FVA (foreign value-added embodied in total exports) and IVA (indirect domestic value-added embodied in intermediate exports used in other countries’ exports) are the key value-added components of total exports. Moreover, the ratio between these two components provides a measure of country/industry relative upstreamness/downstreamness (i.e. the GVC position index). Since the GVC participation index is a linear combination of IVA and FVA, the parameters associated with these components of gross exports are jointly considered indicators of GVC participation.

Table 9.5 presents the results of the value added and GVC estimates. Unfortunately, due to data constraints, we can run the latter test only for a restricted sample of exporting firms from the four LAC countries for which TiVA data are available (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico). 22 The results are fully consistent with the theory and with the results of the previous empirical exercises (the coefficients of the base model are all significant and show the expected signs): firms’ international linkages are positively correlated with productivity. There appears to be an additional and heterogeneous impact on firm productivity in clustering firms by trade in value added (specifically in value added embodied in foreign intermediate imports) once the causal impact of gross exports is controlled for. These estimates confirm that international trade participation has a positive effect on productivity at the firm level and suggest it is not independent of the decomposition of the added value of gross exports by industry. Furthermore, the robust and positive relationship between firm-level productivity and the industry GVC position suggests that the position of the industry in the GVC matters as well: the higher the industry upstreamness in the GVC, the greater the impact of its international linkages on firm productivity. In other words, firms operating in the industries that get added value from exporting intermediates and primary goods used in other countries’ exports tend to be more productive than firms operating in industries whose value added comes primarily from imported inputs.

Conclusions

In this chapter, we have addressed two key research questions:

-

1.

Are firms characterized by international linkages more productive than firms that are not?

-

2.

Are firms that belong to industries more involved in GVCs even more productive?

Our empirical analysis provides a rich picture of the relationship between firm performance and country/industry involvement in international production networks in the LAC region by combining the WBES firm-level data and the OECD-WTO TiVA data.

First, we estimated the productivity premiums associated with participation in trade and the presence of inward FDI, while controlling for firm heterogeneity by using dummies for country, sector, and survey waves. Second, we analyzed the relationship between firm international linkages and productivity by using a standard output function with constant returns to scale Cobb–Douglas technology with labor, capital, and knowledge, presenting both OLS, IV, and CF estimates. Third, we ran a final test of the same equation expanded to account for TIVA-based indicators of value-added trade and industry involvement in global production networks.

Our empirical analysis confirmed a positive causal relationship between international activities and firm performance in the LAC region. Furthermore, focusing on four big LAC countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Mexico), we showed that the level of involvement in GVCs matters as well. More specifically, our empirical analysis highlighted the key role of both trade in value added and GVC position, with a positive impact of upstreamness on firm performance. Firms operating in the industries exporting intermediates and primary goods used in other countries’ exports tend to be more productive than firms operating in industries whose value-added comes primarily from imported inputs.

We suggest that research into constraints preventing a country from fuller engagement in GVCs would be a natural next step to our research. We also believe it will be important to propose adequate criteria to prioritize different constraints depending on whether a country tries to go upstream or to integrate downstream, or to broaden the variety of its exports and opportunities to attract greater GVC participation. Research to assess feasible changes in the business or policy environment in relation to the above factors is alsonecessary.

References

Ahmad, N. 2013. Measuring Trade in Value Added, and Beyond. Paper prepared for the Conference on Measuring the Effects of Globalization, February 28–March 1 in Washington, DC.

Aitken, B.J., and A.E. Harrison. 1999. Do Domestic Firms Benefit from Direct Foreign Investment? Evidence from Venezuela. American Economic Review 89(3): 605–618.

Álvarez, R., and R. López. 2005. Exporting and Performance: Evidence from Chilean Plants. Canadian Journal of Economics 38(4): 1384–1400.

Antràs, P., D. Chor, T. Fally, and R. Hillberry. 2012. Measuring the Upstreamness of Production and Trade Flows. American Economic Review 102(3): 412–416.

Arnold, J.M., and B. Javorcik. 2005. Gifted Kids or Pushy Parents? Foreign Acquisitions and Plant Performance in Indonesia. Discussion Paper 5065. Washington, DC: Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR).

Barba Navaretti, B., and D. Castellani. 2004. Investments Abroad and Performance at Home: Evidence from Italian Multinationals. Discussion Paper 4284. Washington, DC: CEPR.

Barba Navaretti, B., D. Castellani, and A.C. Disdier. 2006. How Does Investing in Cheap Labour Countries Affect Performance at Home? France and Italy. Discussion Paper 5765. Washington, DC: CEPR.

Bernard, A.B., and J.B. Jensen. 1999. Exceptional Exporter Performance: Cause, Effect, or Both? Journal of International Economics 47: 1–25.

Bernard, A., J. Eaton, B. Jensen, and S. Kortum. 2003. Plants and Productivity in International Trade. American Economic Review 93(4): 1268–1290.

Bertrand, O., and H. Zitouna. 2008. Domestic Versus Cross-Border Acquisitions: Which Impact on the Target Firms’ Performance? Applied Economics 40(17): 2221–2238.

Blyde, J.S. (ed.). 2014. Synchronized Factories: Latin America and the Caribbean in the Era of Global Value Chains. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank and Springer Open.

Cattaneo, O., G. Gereffi, S. Miroudot, and D. Taglioni. 2013. Joining, Upgrading and Being Competitive in Global Value Chains: A Strategic Framework. Policy Research Working Paper 6406. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Chen, W. 2011. The Effect of Investor Origin on Firm Performance: Domestic and Foreign Direct Investment in the United States. Journal of International Economics 83(2): 219–228.

Clerides, S.K., S. Lach, and J. Tybout. 1998. Is Learning by Exporting Important? Micro-Dynamic Evidence from Colombia, Mexico, and Morocco. Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(3): 903–947.

Contreras, O.F., J. Carrillo, and J. Alonso. 2012. Local Entrepreneurship Within Global Value Chains: A Case Study in the Mexican Automotive Industry. World Development 40(5): 1013–1023.

Conyon, M.J., S. Girma, S. Thompson, and P.W. Wright. 2002. The Productivity and Wage Effects of Foreign Acquisition in the United Kingdom. Journal of Industrial Economics 50(1): 85–102.

De La Cruz, J., R. Koopman, and Z. Wang. 2011. Estimating Foreign Value-Added in Mexico’s Manufacturing Exports. Working Paper No. 2011-04. Washington, DC: U.S. International Trade Commission.

De Loecker, J. 2007. Do Exports Generate Higher Productivity? Evidence from Slovenia. Journal of International Economics 73(1): 69–98.

Dussel Peters, E. 2003. Ser maquila o no ser maquila, ¿es ésa la pregunta? Comercio Exterior 53(4): 328–336.

Fafchamps, M., S. El Hamine, and A. Zeufack. 2008. Learning to Export: Evidence from Moroccan Manufacturing. Journal of African Economies 17(2): 305–355.

Fally, T. 2012. Production Staging: Measurement and Facts. Boulder, CO: University of Colorado.

Farole, T., and D. Winkler. 2012. Foreign Firm Characteristics, Absorptive Capacity and the Institutional Framework. The Role of Mediating Factors for FDI Spillovers in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Policy Research Working Paper 6265. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Fernandez, A., and A. Isgut. 2005. Learning-by-Doing, Learning-by-Exporting, and Productivity: Evidence from Colombia. Policy Research Working Paper 3544. Washington, DC: The World Bank.

Fukao, K., K. Ito, H.U. Kwon, and M. Takizawa. 2006. Cross-Border Acquisitions and Target Firms’ Performance: Evidence from Japanese Firm-Level Data. Working Paper 12422. Cambridge, MA: The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Gereffi, G., J. Humphrey, and T. Sturgeon. 2005. The Governance of Global Value Chains. Review of International Political Economy 12(1): 78–104.

Girma, S. 2005. Technology Transfer from Acquisition FDI and the Absorptive Capacity of Domestic Firms: An Empirical Investigation. Open Economies Review 16(2): 175–187.

Girma, S., D. Greenaway, and R. Kneller. 2004. Does Exporting Increase Productivity? A Microeconometric Analysis of Matched Firms. Review of International Economics 12(5): 855–866.

Girma, S., R. Kneller, and M. Pisu. 2007. Do Exporters Have Anything to Learn from Foreign Multinationals? European Economic Review 51(4): 993–1010.

Greenaway, D., and R. Kneller. 2007. Firm Heterogeneity, Exporting and Foreign Direct Investment. Economic Journal 117(517): 134–161.

Grossman, G., and E. Helpman. 1991. Innovation and Growth in the World Economy. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Harris, R., and C. Robinson. 2002. The Effect of Foreign Acquisitions on Total Factor Productivity: Plant-Level Evidence from UK Manufacturing, 1987–1992. The Review of Economics and Statistics 84(3): 562–568.

Hayakawa, K., T. Machikita, and F. Kimura. 2012. Globalization and Productivity: A Survey of Firm-Level Analysis. Journal of Economic Surveys 26(2): 332–350.

Helpman, E., M.J. Melitz, and S.R. Yeaple. 2004. Export versus FDI With Heterogeneous Firms. American Economic Review 94(1): 300–316.

Hijzen, A., T. Inui, and Y. Todo. 2007. The Effects of Multinational Production on Domestic Performance: Evidence from Japanese Firms. Discussion Paper 07-E-006. Tokyo: Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI).

Hijzen, A., S. Jean, and T. Mayer. 2006. The Effects at Home of Initiating Production Abroad: Evidence from Matched French Firms. Mimeo. Paris: Centre d’Etudes Prospectives et d’Informations Internationales.

Hummels, D., J. Ishii, and K. Yi. 2001. The Nature and Growth of Vertical Specialization in World Trade. Journal of International Economics 54(1): 75–96.

Iossifov, P. 2014. Cross-Border Production Chains and Business Cycle Co-movement Between Central and Eastern European Countries and Euro Area Member States. Working Paper Series no. 1628. Washington, DC: European Central Bank.

Ito, Y. 2007. Choice for FDI and Post-FDI Productivity. Discussion Paper 07-E-049. Tokyo: RIETI.

Johnson, R.C., and G. Noguera. 2012a. Accounting for Intermediates: Production Sharing and Trade in Value Added. Journal of International Economics 86: 224–236.

Johnson, R.C., and G. Noguera. 2012b. Fragmentation and Trade in Value Added Over Four Decades. Working paper 18186. Cambridge, MA: NBER.

Kimura, F., and K. Kiyota. 2006. Exports, FDI, and Productivity: Dynamic Evidence from Japanese Firms. Review of World Economics 142(4): 695–719.

Koopman, R., W. Powers, Z. Wang, and S.J. Wei. 2011. Give Credit to Where Credit Is Due: Tracing Value Added in Global Production Chains. Working Papers Series 16426. Cambridge, MA: NBER.

Koopman, R., Z. Wang, and S.J. Wei. 2014. Tracing Value-Added and Double Counting in Gross Exports. American Economic Review 104(2): 459–494.

Lederman, D. 2010. An International Multilevel Analysis of Product Innovation. Journal of International Business Studies 41(4): 606–619.

Lederman, D. 2013. International Trade and Inclusive Growth: A Primer. Indian Growth and Development Review 6(1): 88–112.

Lileeva, A., and D. Trefler. 2007. Improved Access to Foreign Markets Raises Plant-Level Productivity for Some Plants. Working Paper 13297. Cambridge, MA: NBER.

López, R. 2005. Trade and Growth: Reconciling the Macroeconomic and Microeconomic Evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys 19(4): 623–648.

Martins, P.S., and Y. Yang. 2009. The Impact of Exporting on Firm Productivity: A Meta-Analysis of the Learning-by-Exporting Hypothesis. Review of World Economics 145: 431–445.

Melitz, M. 2003. The Impact of Trade on Intra-Industry Reallocations and Aggregate Industry Productivity. Econometrica 71(6): 1695–1725.

Miroudot, S., and A. Ragousssis. 2009. Vertical Trade, Trade Costs and FDI. Trade Policy Working Paper 89. Paris: OECD.

Murakami, Y. 2005. Are Multinational Enterprises More Productive? A Test of the Selection Hypothesis. Journal of Asian Economics 16(2): 327–339.

OECD–WTO. 2012. Trade in Value-Added: Concepts, Methodologies, and Challenges. Joint OECD–WTO Note. Washington, DC: OECD–WTO. http://www.oecd.org

Park, A., D. Yang, X. Shi, and Y. Jiang. 2010. Exporting and Firm Performance: Chinese Exporters and the Asian Financial Crisis. The Review of Economics and Statistics 92(4): 822–842.

Petkova, N. 2008. Does Foreign Ownership Lead to Higher Firm Productivity? Mimeo. Eugene, OR: University of Oregon, Department of Finance.

Pietrobelli, C., and R. Rabellotti. 2011. Global Value Chains Meet Innovation Systems: Are There Learning Opportunities for Developing Countries? World Development 39(7): 1261–1269.

Piscitello, L., and L. Rabbiosi. 2005. The Impact of Inward FDI on Local Companies’ Labour Productivity: Evidence from the Italian Case. International Journal of the Economics of Business 12(1): 35–51.

Salis, S. 2008. Foreign Acquisition and Firm Productivity: Evidence from Slovenia. The World Economy 31(8): 1030–1048.

Serti, F., and C. Tomasi. 2008. Self-Selection and Post-Entry Effects of Exports: Evidence from Italian Manufacturing Firms. Review of World Economics 144(4): 660–694.

Stehrer, R. 2013. Accounting Relations in Bilateral Value Added Trade. Working Paper. Vienna: The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW).

Timmer, M.P., E. Dietzenbacher, B. Los, R. Stehrer, and G.J. de Vries. 2014. The World Input-Output Database: Contents, Concepts and Applications. Research Memorandum 144. Groningen, The Netherlands: Groningen Growth and Development Centre (GGDC).

UNCTAD. 2013. World Investment Report 2013: Global Value Chains: Investment and Trade for Development. New York and Geneva: United Nations.

Van Biesebroeck, J. 2005. Exporting Raises Productivity in Sub-Saharan African Manufacturing Plants. Journal of International Economics 67(2): 373–391.

Verhoogen, E. A. 2007. Trade, quality upgrading and wage inequality in the Mexican manufacturing sector. Discussion Paper 2913. Bonn, Germany: IZA.

Wagner, J. 2007. Exports and Productivity: A Survey of the Evidence from Firm-Level Data. World Economy 30(1): 60–82.

Wooldridge, J.M. 2010. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Appendices

Appendix

Notes

-

1.

The learning effect has not been fully examined theoretically in the literature. The major exceptio n is Clerides et al. (1998).

-

2.

See Girma et al. (2004) for UK firms; Van Biesebroeck (2005) for sub-Saharan African countries; Fernandez and Isgut (2005) for Colombia; Álvarez and López (2005) for Chile; De Loecker (2007) for Slovenia; Lileeva and Trefler (2007) and Serti and Tomasi (2008) for Italy; and Park et al. (2010) for China.

-

3.

Papers analyzing the learning effect in investing for multinational enterprises include, among others, Aitken and Harrison (1999) for Venezuela; Murakami (2005), Kimura and Kiyota (2006), Hijzen et al. (2007), and Ito (2007) for Japan; Barba Navaretti and Castellani (2004) for Italy; and Hijzen et al. (2006) and Barba Navaretti et al. (2006) for France.

-

4.

Arnold and Javorcik (2005) and Petkova (2008) for Indonesia; Conyon et al. (2002), Girma (2005), Girma et al. (2007), and Harris and Robinson (2002) for the United Kingdom; Bertrand and Zitouna (2008) for France; Salis (2008) for Slovenia; Piscitello and Rabbiosi (2005) for Italy; Fukao et al. (2006) for Japan; and Chen (2011) for the United States.

-

5.

Hummels et al. (2001); Johnson and Noguera (2012a), (2012b); Miroudot and Ragousssis (2009); Koopman et al. (2011), (2014); De La Cruz et al. (2011); Stehrer (2013).

-

6.

The World Input-Output Database (WIOD) is a related but separate data initiative funded by the European Commission and developed by the University of Groningen, based on individual countries’ supply-and-use tables (Timmer et al. 2014). Another source of data, characterized by a further level of detail, is the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP), which is not grounded in official national I/O and does not distinguish trade flows between intermediate and final consumption.

-

7.

The current TiVA version provides 39 indicators for 57 countries (34 OECD countries plus 23 other economies, including Argentina, Brazil, China, India, Indonesia, the Russian Federation, and South Africa) with a breakdown into 18 industries. As for the WBES, the industry classification is based on the ISIC Rev. 3.1. The time coverage includes the years 1995, 2000, 2005, 2008, and 2009.

-

8.

We note a caveat in this decomposition at the industry level. While the value added embedded in a given imported intermediate could travel across many sectors before it is exported, the adopted decomposition traces only the direct and indirect effects.

-

9.

The WBES uses a stratified random sampling method where the strata are business sector, location, and firm size (for additional details on the WBES dataset see Chap. 1). We take this into account in our empirical exercises by using a full set of industry and country dummies.

-

10.

We use the firm-level data from the 2010 WBES survey for Argentina, Chile, and Mexico since the information collected in the surveys refers to characteristics of the firm to the last completed fiscal year (2009), and the 2009 WBES survey for Brazil.

-

11.

Further details on this analysis by industry for each of the four LAC countries are available from the authors on request.

-

12.

Exporters are only those firms that directly export more than 10 % of total sales.

-

13.

Because of the adopted threshold of 10 % of exports on total sales, the registered export intensity is slightly higher than that reported in similar analyses (see, among others, Lederman 2010, 2013).

-

14.

For the industrialized economies, we selected the United States, Japan, and Germany; for the emerging economies, we selected China, India, and South Korea; and for the developing/transitioning economies, we selected Poland, Turkey, and South Africa.

-

15.

For a given industry, the index measures how many stages of production are left before the goods or services produced by this industry reach final consumers. High index values are associated with industries that are more involved in upstream activities, while lower values correspond with industries specialized in downstream activities and, therefore, closer to final consumption.

-

16.

As is common in the literature, we consider a firm to be foreign-owned only if the foreign ownership is 10 % or higher.

-

17.

Although labor productivity is a quite imperfect measure of firm productivity, our cross-sectional dataset does not allow us to calculate total factor productivity using standard methodologies.

-

18.

For instance, country dummies capture the heterogeneity in price differences across countries.

-

19.

It can be argued that better performing firms are more likely to prepare trade documents and shipments better and thereby spend less time in customs or in getting a license. However, in our case, the weak correlation between firm labor productivity and the above instruments confirms that these trade obstacles are more related to causes that are external to firms (e.g. procedures, institutional efficiency, etc.).

-

20.

The number of micro-firms is not sufficient to carry out these empirical analyses for the subsample of exporting firms.

-

21.

The lack of significance of the ρ coefficient is normally considered a reliable test for the absence of endogeneity bias. This assumption is not rejected in all of our estimates with the relevant exception of the subsample of large firms.

-

22.

Moreover, in this exercise we cannot further test the hypothesis of absence of endogeneity due to reverse causality. The positive outcomes of the tests in the previous empirical exercises make us confident that this condition holds even when it is not directly testable.

Rights and permissions

This chapter is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

Copyright information

© 2016 Inter-American Development Bank

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Montalbano, P., Nenci, S., Pietrobelli, C. (2016). International Linkages, Value-Added Trade, and Firm Productivity in Latin America and the Caribbean. In: Inter-American Development Bank, Grazzi, M., Pietrobelli, C. (eds) Firm Innovation and Productivity in Latin America and the Caribbean. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-58151-1_9

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-58151-1_9

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN: 978-1-349-58150-4

Online ISBN: 978-1-349-58151-1

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)