Abstract

Many studies have reported evidence for solar-forcing of Holocene climate change across a range of archives. These studies have compared proxy-climate data with records of solar variability (e.g. 14C or 10Be), or have used time series analysis to test for the presence of solar-type cycles. This has led to some climate sceptics misrepresenting this literature to argue strongly that solar variability drove the rapid global temperature increase of the twentieth century. As proxy records underpin our understanding of the long-term processes governing climate, they need to be evaluated thoroughly. The peatland archive has become a prominent line of evidence for solar forcing of climate. Here we examine high-resolution peatland proxy climate data to determine whether solar signals are present. We find a wide range of significant periodicities similar to those in records of solar variability: periods between 40–100 years, and 120–140 years are particularly common. However, periodicities similar to those in the data are commonly found in random-walk simulations. Our results demonstrate that solar-type signals can be the product of random variations alone, and that a more critical approach is required for their robust interpretation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last 50 years there has been considerable interest in the relationship between solar variability and climate1,2,3. Studies from a range of sedimentary archives have investigated the role of solar forcing through comparisons of proxy climate data with reconstructions of solar activity3,4,5,6,7,8. Reconstructions of solar activity are based on concentrations of cosmogenic isotopes (e.g. 14C found in tree-rings and 10Be in ice cores) which form in the upper atmosphere and are modulated by the effects of changing solar activity on galactic cosmic ray flux6. Using this approach, numerous studies have reported evidence for solar-forced climate change during the Holocene epoch3,5,9. Furthermore, researchers have reported solar cycles in proxy climate data based on the results of spectral and wavelet analytical techniques4,8. Several papers reporting a solar-climate link have been used by climate sceptics as evidence of solar variability driving recent warming, implying that atmospheric carbon dioxide has a less important influence on global temperature10.

A number of climate proxies have been used in investigations of solar-forced climate change including geochemical and biological records from marine and lake sediments3,5,11, tree rings12, lake levels13 and glacial fluctuations14. In addition, palaeohydrological proxies from ombrotrophic (rain-fed) peatlands have been used to investigate Holocene solar-climate relationships1,15,16,17. Shifts in peat hydrology sometimes coincide with changes in solar activity during the mid- and late-Holocene15,18,19. The proposed mechanisms of solar-forced climate change include a complex series of ocean-atmosphere feedbacks driven primarily by changes in UV and solar wind20. The resultant variation in atmospheric circulation, temperature and precipitation would drive changes in peatland hydrology3,20. Global-scale climate response to solar forcing has also been inferred through comparison of peat profiles in Europe1,15 and N and S America17,21. In addition, spectral analysis has revealed periodicities in peat-based proxies that are similar to those found in cosmogenic isotope records of solar variability16,19,22. These periodicities have been frequently interpreted as periodic changes in climate, reflecting multi-decadal to centennial solar cycles22.

However, Holocene climate proxies are noisy and have chronological errors that often lead to considerable temporal uncertainties in reconstructions7,23. Quasi-random variations that arise from complex, non-linear autogenic fluctuations can themselves cause ecosystem changes including abrupt events, long-term trends and even quasi-cyclic behaviour24. Climate reconstructions derived from biological proxies in ombrotrophic peatlands rely on the assumption that down-core changes in species composition are driven by climate variability25. Whilst there is often ample evidence to suggest that hydrology is the strongest environmental control on taxa used in reconstructions (e.g. testate amoebae), other factors, such as competition, pH and trophic status may also play an important role26. We address the question of whether periodicities found in peat-based palaeoclimate records truly reflect changing solar activity, or whether they could also be explained by random variations or artefacts of sampling intervals and/or chronological errors.

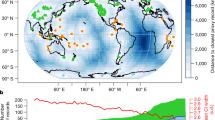

We examined nine high-resolution proxy climate records from ombrotrophic bogs in Europe and the USA (Fig. 1, Supplementary Methods S1). These proxy records have high quality age control and robust age-depth relationships based on Bayesian models (Supplementary Fig. S2). Spectral and wavelet analyses were used to identify solar-type signals in the peat record, while the sunspot reconstruction of Solanki et al.27 was used as the record of changing solar activity through the mid-late Holocene. We also developed random walk simulations (RWs) – a non-stationary stochastic ‘red noise’ time series where values wander randomly over time (ref. 28; Supplementary Fig. S3). These simple simulations can exhibit complex features such as those found in palaeoenvironmental data24. We sampled fifteen RWs per site at the same time interval as the real proxy data to see if similar periodicities could be found in random simulations. We also generated an additional 5000 RWs sampled to a regular time interval of 10 years which we tested for significant positive correlation with the solar record. We used these to test a null hypothesis that such variations are the product of random variations. We selected one RW per site with features that plausibly imitate ‘real’ proxy reconstructions, such as rapid changes and quasi-cyclic patterns, for further detailed statistical analysis to illustrate our argument.

(A) Normalised water-table reconstruction from Ballyduff, Derragh, Dead Island, Slieveanorra (Ireland), Butterburn and Malham (England), Minden and Sidney (USA). The record from Great Heath (USA) is Sphagnum/Vascular Ratio based on ratios of leaf wax compounds. A loess smoothing function is illustrated (red line). The chronologies have been modelled using a Bayesian statistical approach (Supplementary Fig. S2). Reconstructed sunspot numbers (Solanki et al.27) and sunspot counts (blue line; source: SILSO data/image, Royal Observatory of Belgium, Brussels), and the combined CO2 record from Mauna Loa, the Law Dome and EPICA Dome C ice cores (See refs in Supplementary Method S1). (B) An example random walk simulation for each site (sampled to the same chronological spacing as the real data) is also shown.

There are well-established climatic events in some of the peat-based records including the 2.7 ka BP year event, Medieval Warm Period, and the Little Ice Age (Fig. 1). The records indicate that rapid change in the last ~100 years is coincident with both the large increase in global atmospheric CO2 concentration and a rise in sunspot numbers. There are periods in the record where shifts in the proxy climate data correspond with excursions in solar activity (Fig. 1). There are also significant correlations between the proxy records from four of our nine sites and the solar reconstruction (Supplementary Table S7). Many previous studies have used running correlation analyses between records of solar variability and proxy climate data time series to interrogate the relationship between solar forcing and Holocene climate change11,29. Our analysis (Supplementary Fig. S7) shows that the running correlations between the proxy climate records and solar variability are highly variable in time for both 100-year and 500-year windows; however, when an appropriate Monte Carlo significance testing procedure is used (Supplementary Data S8) it is mostly non-significant (p > 0.10). Some studies have utilised significance testing procedures that are not appropriate for time series data as they do not account for the multiple comparison problem11,29. There are also significant correlations and running correlations between the RWs and the solar record, four of which are similar to or even stronger than those found for the ‘real’ data (Supplementary Fig. S7). Interestingly, 45% of the 5000 RWs were positively correlated with the solar record (Supplementary Fig. S9). Given that these are purely random data, it is quite remarkable that nearly half of these RWs show this level of correlation. This poses the question of whether solar-type cycles in proxy climate records can be robustly linked to solar variability.

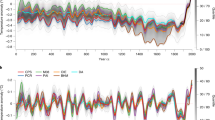

Spectral analysis shows that there are a large number of significant, high-frequency periodicities present in the real data (Fig. 2). Commonly occurring periodicities span the ranges 40–100 years (n = 113 > 90% false alarm level), and 120–140 years (n = 17 > 90% false alarm level). In addition, our analysis of previous studies has shown the prominence of 80–90, 130–140, 200–210 and 260–270 year periodicities in peat-based climate records (Supplementary Table S6). However, caution is needed when interpreting these results as there may be a publication bias: the focus of several of these studies was to present evidence for solar-forcing of Holocene climate. Low-frequency periodicities were also present in both the real and RW data (Fig. 2), but millennial-scale climatic changes may be poorly preserved in peatlands due to signal-shredding or over-writing by autogenic processes such as ecohydrological feedbacks and secondary decomposition25. Additionally, the maximum time period covered by the peat cores in this study is 7 k years, rendering millennial-scale periodicities more questionable.

(A) All periodicities in the random walks over 90% false alarm level; (B) All periodicities in the proxy climate records over 90% false alarm level; (C) Highest power periodicities in the proxy climate records over 90% false alarm level; (D) Periodicities with a period ≤500 years in random walks over 90% false alarm level; (E) Periodicities with a period ≤500 years in the proxy climate records over 90% false alarm level; (F) Highest power periodicities in the proxy climate records over 90% false alarm level ≤500 years. Solar cycle bands commonly reported in palaeoclimate literature are illustrated.

The periodicities reported here and in previous studies are present in the solar reconstruction (Fig. 3A) and match the range of the Gleissberg cycle (~70–100 years) and sub-harmonics of the Hale cycle (~132 years)30, de Vries cycle (~200–210 years) and others present in the 14C record (105, 131, 232, 385, 504, 805, 2,241 years: ref. 31). These cycles have also been shown to be prominent in other Holocene proxy climate records9,16. However, similar significant periods are also found in the analysis of RWs (Fig. 2). Periods similar to solar cycles are particularly common: 80–160 years and a clear peak at 120–140 years. Another peak spanning 200–220 is present (Fig. 2) that matches exactly the period of the de Vries solar cycle. Interestingly, 200–220 year periods are mostly absent from the real proxy climate data. Wavelet and Cross-Wavelet analyses illustrate clearly that any relationships between solar variability and the proxy climate records are temporally variable, inconsistent between records, and show phases of correspondence and non-correspondence. These discrepancies seem likely to result from some combination of: i) the sensitivity of a proxy to climate drivers; ii) differences in temporal resolution within a record driven by changes in sedimentation rate; and/or iii) differences in sampling resolution between reconstructions (Supplementary Fig. S5). The lack of consistency in correspondence through time and between sites is clear, suggesting that either the sites have exhibited variable sensitivity to solar-forced climate change over time, or that solar variability is not driving the variability in the proxy data (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S5).

The black lines signify 95% significant levels against a lag1 (red noise) background. Dead Island is given here as an example: for other sites refer to Supplementary Fig. S5.

Periodicities present in proxies derived from complex environmental systems must be interpreted with caution because such systems possess the potential to modify external (climatic) signals through autogenic mechanisms (e.g. ref. 32, for sedimentary systems). Peat-based proxy climate records can exhibit amplified, damped or phase-shifted representations of climatic influences through mechanisms such as vegetation succession33 and a range of negative feedback mechanisms that can lead to a degree of homeostasis in system behaviour25,34.

The most common significant periodicities found here (within the ranges 40–100 years and 120–140 years) could be interpreted as evidence for solar-forced climate change because they match the ranges of cycles in solar reconstructions. However, similar periodicities are also prominent in the random-walk simulations. Thus, we propose that many of the periodicities found are the product of either: i) random variations; ii) autogenic mechanisms in a complex environmental system; iii) the sampling resolution; iv) the age model applied; or v) some combination of the above factors. Our analysis illustrates the importance of replication to avoid erroneous attribution of periodicities to external forcing. Large ensembles of well-dated Holocene proxy climate data are necessary for robust testing of solar signals in Holocene proxy climate records16,35, because they filter local, non-climatic effects and reveal persistent variations, some of which may well be associated with past solar variability. In dealing with time series analysis, care should be taken when attributing cyclical behaviour to solar forcing because such signals could merely be the product of random variations, non-climatic (e.g. autogenic) factors or the temporal-expression of the sampling strategy. We contend that many solar-type cycles reported in the palaeoclimatological literature may potentially be artefacts.

Method

We examined nine high-resolution proxy climate records from ombrotrophic bogs located in the Northern Hemisphere (USA and Europe; Fig. 1, Supplementary Methods S1). Eight of these records are based on transfer function-reconstructions of water-table depth from testate amoebae microfossils in the peat and one is based on Sphagnum/Vascular Ratio determined through ratios of leaf wax compounds (see Supplementary Methods S1 for full details). Age-depth models for the proxy palaeohydrological records were generated from radiocarbon dates and age-equivalent stratigraphic markers (tephra, spheroidal carbonaceous particles) using a Bayesian statistical modelling approach. A series of 15 random walks per site were generated (based on each dataset) and time-steps were matched to the corresponding proxy (e.g. Dead Island = 4454 years) from an initial value of zero. The sunspot reconstruction of Solanki et al.27 was used as the record of changing solar activity through the mid-late Holocene. Spectral and wavelet analyses were used to determine periodicities in the data, and cross-wavelet analysis was used to determine the temporal relationship between the proxy data and the sunspot reconstruction. The significance of periodicities was tested against appropriate noise background models. Bivariate running correlation analysis (time windows = 100 and 500 years) was used to determine the correlation between the solar record and the proxy climate data and the temporal variation of the correlation. The statistical significance of the correlation was calculated using a Monte Carlo simulation to determine the null distribution. An additional 5000 random walks were generated and tested for significant positive correlation (Spearman’s Rank, p < 0.05) with the solar reconstruction27. For full methods see Supplementary Methods S1.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Turner, T. E. et al. Solar cycles or random processes? Evaluating solar variability in Holocene climate records. Sci. Rep. 6, 23961; doi: 10.1038/srep23961 (2016).

Change history

27 June 2016

A correction has been published and is appended to both the HTML and PDF versions of this paper. The error has not been fixed in the paper.

27 June 2016

Scientific Reports 6: Article number: 23961 published online: 05 April 2016; updated: 27 June 2016. A coding error in the Monte Carlo procedure for the determination of critical values in running correlation analysis (presented in Supplementary Data S8) has been brought to the attention of the authors.

References

Mauquoy, D., Yeloff, D., Van Geel, B., Charman, D. J. & Blundell, A. Two decadally resolved records from north-west European peat bogs show rapid climate changes associated with solar variability during the mid–late Holocene. J. Quaternary Sci. 23, 745–763 (2008).

Gray, L. J. et al. Solar influences on climate. Reviews of Geophysics 48, RG4001 (2010) doi: 10.1029/2009RG000282.

Bond, G. et al. Persistent Solar Influence on North Atlantic Climate During the Holocene. Science 294, 2130–2136 (2001).

Patterson, R. T., Prokoph, A. & Chang, A. Late Holocene sedimentary response to solar and cosmic ray activity influenced climate variability in the NE Pacific. Sediment. Geol. 172, 67–84 (2004).

Haltia-Hovi, E., Saarinen, T. & Kukkonen, M. A 2000-year record of solar forcing on varved lake sediment in eastern Finland. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 26, 678–689 (2007).

Steinhilber, F. et al. 9,400 years of cosmic radiation and solar activity from ice cores and tree rings. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 5967–5971 (2012).

Swindles, G. T. et al. Centennial-scale climate change in Ireland during the Holocene. Earth-Sci. Rev. 126, 300–320 (2013).

Stuiver, M., Grootes, P. M. & Braziunas, T. F. The GISP2 δ18O Climate Record of the Past 16,500 Years and the Role of the Sun, Ocean, and Volcanoes. Quaternary Res. 44, 341–354 (1995).

Duan, F. et al. Evidence for solar cycles in a late Holocene speleothem record from Dongge Cave, China. Sci. Rep. 4, 5159 (2014) doi: 10.1038/srep05159.

Loehle, C. & Scafetta, N. Climate Change Attribution Using Empirical Decomposition of Climatic Data. The Open Atmospheric Science Journal 5, 74–86 (2011).

Kokfelt, U. & Muscheler, R. Solar forcing of climate during the last millennium recorded in lake sediments from northern Sweden. The Holocene 23, 447–452 (2013).

Muraki, Y., Masuda, K., Nagaya, K., Wada, K. & Miyahara, H. Solar variability and width of tree ring. Astrophys. Space Sci. Trans. 7, 395–401 (2011).

Magny, M. Holocene climate variability as reflected by mid-European lake-level fluctuations and its probable impact on prehistoric human settlements. Quatern Int. 113, 65–79 (2004).

Karlén, W. & Kuylenstierna, J. On solar forcing of Holocene climate: evidence from Scandinavia. The Holocene 6, 359–365 (1996).

van Geel, B., Buurman, J. & Waterbolk, H. T. Archaeological and palaeoecological indications of an abrupt climate change in The Netherlands, and evidence for climatological teleconnections around 2650 BP. J. Quaternary Sci. 11, 451–460 (1996).

Swindles, G. T., Patterson, R. T., Roe, H. M. & Galloway, J. M. Evaluating periodicities in peat-based climate proxy records. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 41, 94–103 (2012).

Nichols, J. E. & Huang, Y. Hydroclimate of the northeastern United States is highly sensitive to solar forcing. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L04707 (2012) doi: 10.1029/2011GL050720.

Blaauw, M., van Geel, B. & van der Plicht, J. Solar forcing of climatic change during the mid-Holocene: indications from raised bogs in The Netherlands. The Holocene 14, 35–44 (2004).

Turner, T. E., Swindles, G. T. & Roucoux, K. H. Late Holocene ecohydrological and carbon dynamics of a UK raised bog: impact of human activity and climate change. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 84, 65–85 (2014).

van Geel, B. et al. The role of solar forcing upon climate change. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 18, 331–338 (1999).

Chambers, F. M., Mauquoy, D., Brain, S. A., Blaauw, M. & Daniell, J. R. G. Globally synchronous climate change 2800 years ago: Proxy data from peat in South America. Earth Planet. Sc. Lett. 253, 439–444 (2007).

Chambers, F. M. & Blackford, J. J. Mid- and late-Holocene climatic changes: a test of periodicity and solar forcing in proxy-climate data from blanket peat bogs. J. Quaternary Sci. 16, 329–338 (2001).

Blaauw, M., Christen, J. A., Mauquoy, D., van der Plicht, J. & Bennett, K. D. Testing the timing of radiocarbon-dated events between proxy archives. The Holocene 17, 283–288 (2007).

Blaauw, M., Bennett, K. D. & Christen, J. A. Random walk simulations of fossil proxy data. The Holocene 20, 645–649 (2010).

Morris, P. J., Baird, A. J., Young, D. M. & Swindles, G. T. Untangling climate signals from autogenic changes in long-term peatland development. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 10,788–10,797 (2015) doi: 10.1002/2015GL066824.

Turner, T. E., Swindles, G. T., Charman, D. J. & Blundell, A. Comparing regional and supra-regional transfer functions for palaeohydrological reconstruction from Holocene peatlands. Palaeogeogr Palaeocl 369, 395–408 (2013).

Solanki, S. K., Usoskin, I. G., Kromer, B., Schussler, M. & Beer, J. Unusual activity of the Sun during recent decades compared to the previous 11,000 years. Nature 431, 1084–1087 (2004).

Özel, G. in Handbook of Research on Behavioral Finance and Investment Strategies (ed Copur, Z. ) Ch. 11, 191–193 (IGI Global, 2015).

Jiang, H. et al. Solar forcing of Holocene summer sea-surface temperatures in the northern North Atlantic. Geology (2015) doi: 10.1130/G36377.1.

Attolini, M. R., Cecchini, S., Galli, M. & Nanni, T. On the persistence of the 22 y solar cycle. Sol. Phys. 125, 389–398 (1990).

Damon, P. E. & Sonett, C. P. in The Sun in Time (eds Sonett, C. P., Giampapa, M. S. & Matthews, M. S. ) 360–388 (University of Arizona Press, 1991).

Jerolmack, D. J. & Paola, C. Shredding of environmental signals by sediment transport. Geophys. Res. Lett. 37, L19401 (2010) doi: 19410.11029/12010GL044638.

Belyea, L. R. & Malmer, N. Carbon sequestration in peatland: patterns and mechanisms of response to climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 1043–1052 (2004).

Swindles, G. T., Morris, P. J., Baird, A. J., Blaauw, M. & Plunkett, G. Ecohydrological feedbacks confound peat-based climate reconstructions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 39, L11401 (2012) doi: 11410.11029/12012GL051500.

Charman, D. J., Blundell, A., Chiverrell, R. C., Hendon, D. & Langdon, P. G. Compilation of non-annually resolved Holocene proxy climate records: Stacked Holocene peatland palaeo-water table reconstructions from northern Britain. Quaternary Sci. Rev. 25, 336–350 (2006).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge NERC Training Grant NE/G52398X/1 to TET.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.E.T. and G.T.S. conceived the project, led the data compilation and wrote the paper; P.J.M. and L.E.P. assisted with interpretation and contributed to manuscript development; D.J.C., P.G.L., R.K.B. and J.E.N. contributed data and helped improve the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in the credit line; if the material is not included under the Creative Commons license, users will need to obtain permission from the license holder to reproduce the material. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

About this article

Cite this article

Turner, T., Swindles, G., Charman, D. et al. Solar cycles or random processes? Evaluating solar variability in Holocene climate records. Sci Rep 6, 23961 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23961

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23961

This article is cited by

-

Holocene centennial variability in sea surface temperature and linkage with solar irradiance

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Mathematical Proof of the Synthetic Running Correlation Coefficient and Its Ability to Reflect Temporal Variations in Correlation

Journal of Ocean University of China (2021)

-

A Review of Statistics in Palaeoenvironmental Research

Journal of Agricultural, Biological and Environmental Statistics (2020)

-

Insignificant influence of the 11-year solar cycle on the North Atlantic Oscillation

Nature Geoscience (2019)

-

Holocene vegetation patterns in southern Lithuania indicate astronomical forcing on the millennial and centennial time scales

Scientific Reports (2019)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.